B.R. Sanders's Blog, page 29

February 13, 2015

Supernatural Haiku: 02×22 – All Hell Breaks Loose Part Two

No one’s mad at you Deano

click through for source

What’s dead should stay dead

unless it’s my brother, Sam.

My soul for his life.

February 11, 2015

Supernatural Haiku: 02×21 – All Hell Breaks Loose Pt. 1

THERE CAN BE ONLY ONE

click through for source

Demon Brood update:

So…there can be only one

(that’s Highlander rules)

February 10, 2015

Supernatural Haiku: 02×20 – What Is And What Should Never Be

February 6, 2015

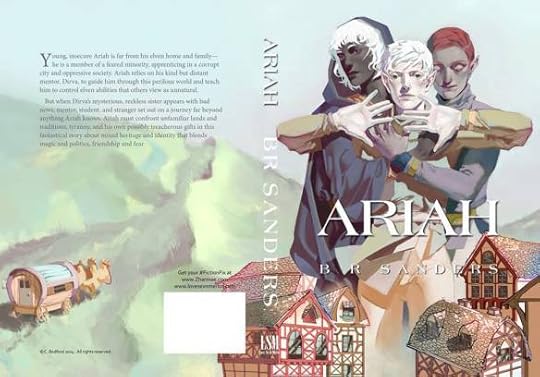

ARIAH cover reveal!

I CANNOT TELL YOU ALL how much I love this cover!! The cover art was created by the enormously talented C. Bedford, and I am honored to have my book represented by her work. If you, too, are enamored of the magic she worked with ARIAH’s cover then I heartily recommend a stroll through C. Bedford’s deviant art page here.

I CANNOT TELL YOU ALL how much I love this cover!! The cover art was created by the enormously talented C. Bedford, and I am honored to have my book represented by her work. If you, too, are enamored of the magic she worked with ARIAH’s cover then I heartily recommend a stroll through C. Bedford’s deviant art page here.

One of the reasons* I signed with LSM/Zharmae was, honestly, the quality of their cover designs. Despite the old adage, everyone really does judge a book by its cover. Covers are important–they communicate the level of professionalism that has gone into the book. They communicate the artistry of the book, the genre, conventions adhered to or broken. They can describe or mislead you about the book’s protagonist. Getting a good cover for ARIAH was important to me.

One of the big decisions, when you write a book nowadays, is whether to go solo and self-publish or to sign with a house. The houses, be they big or small, generally cut the authors out of the cover design process. So if you’re a control freak (and most authors kind of are, especially about how their books are being portrayed) then this part is hard. Trust is involved. Trust is not always easy to have. This time the trust totally worked out.

Zharmae did a wonderful job finding and hiring on C. Bedford. C. Bedford did a wonderful job capturing my characters and my book. Thank you to all parties involved! you about the protagonist.

February 2, 2015

New Pub: “The Demiurge” in THE WILD ONES

I’m thrilled to announce that my short story, “The Demiurge”, is included in the inaugural issue of The Wild Ones: A Quarterly Queer Lit Rage. The issue is available for purchase here, and I encourage y’all to check it out! Here’s a synopsis of the story to whet your appetite:

Sometimes a genius biologist needs an entire island to herself. Sometimes she needs to pursue her work away from the prying and judgmental eyes of everyone else. Temperance, a theologian, understands this about her wife. She whisks Vera way to an isolated island in the Hebrides, and there Temperance watches her wife’s holy genius unfold.

“The Demiurge” is a historical science fiction story brimming with big questions and mad science. Where is the line between science and religion? And when you find that line, should you cross it?

The really lovely thing about short stories, from a writer’s perspective, is that they allow you to step outside your comfort zone for just the right amount of time. There are elements in “The Demiurge” that were easy for me—it’s earnest, it’s speculative, it’s queer—but there were other parts that took me decidedly past what I’m used to as a writer. It’s historical and it’s not a secondary world—set in 19th century Britain. The main POV character, Temperance, grew up wealthy. I so often do not write wealthy characters, and she had a particularly restrained way of thinking that I found very interesting and very challenging to write. I like her, though. I like her secret feistiness.

“The Demiurge” has its roots quite explicitly in Frankenstein. But Frankenstein itself was a treatise on the question of religious and scientific ethics, a set of questions that fascinated me enough that I ended up minoring in religion in college almost by accident. This is one of the few times I’ve explored those haunting questions in my fiction. I’m grateful that it found a home with The Wild Ones.

January 30, 2015

Supernatural Haiku: 02×19 – Folsom Prison Blues

January 27, 2015

Supernatural Haiku – 02×18: Hollywood Babylon

January 20, 2015

Book Review: WHO FEARS DEATH

WHO FEARS DEATH, by Nnedi Okorafor, is not a book for the faint of heart. Told in retrospect to her captors by a woman facing execution—a woman who has changed the world around her in fundamental and unexpected ways and sacrificed herself to do it—the teller does not flinch away from the grisly and vicious details of her story. She revels in them. As much a book about hope and change as it is a book about the horrors of complacency, WHO FEARS DEATH is a book that embraces anger, and for that if nothing else, I loved it.

TRIGGER WARNING: The book has roots in the real-world history of weaponized rape in the Sudan. In the book, Onyesonwu is the product of militarized rape: her Okeke (Black) mother is raped brutally by a Nuru (White) sorcerer, and then her mother is rejected by her husband. Onyesonwu spends her early childhood in the deserts alone with her mother. Her mother notices the child has an affinity for juju—magic—and despite her child’s visible biracial features decides she has to seek out a township and raise her among other people. It’s not easy—people like Onyesonwu, the products of Nuru/Okeke rape are called Ewu and presumed to be inherently violent, inherently broken due to the means of their conception. Finding a village where they are accepted is the first of many battles here.

Onyesonwu grows up and grows into her magic. She becomes a shapeshifter. She demands to be mentored, going up against old barriers that would restrict her both about her being Ewu and a woman. She falls in love. She builds friendships. She learns that her world is being torn apart; she learns of a prophecy that she might be the one to heal it. She goes through an initiation that reveals her own death and unlocks her powerful magic. She prepares herself for the inevitable showdown with the powerful force of a man who created her. Across the narrative, the book manages to tackle genocide, rape, female circumcision, cultural relativism, colorism, and a host of other issues with a deft hand. Onyesonwu’s voice is always harsh, always sharp-tongued and brutal. Always questioning.

Onyesonwu was a narrator I related to immediately. She was so brash, so defiant. So deeply capable of love, and at the same time so reactive and defensive. Entitled and yet so used to being refused. So angry. I loved her anger. I was moved by anger. I connected with it. The book exulted in her anger. It was always her greatest strength. When it was positioned as a weakness—and occasionally it was—it was always done so by the men around her, and thus the weakness they claimed was undercut by the fact that they saw her as an obvious threat to their masculinity. Even the love of her life, Mwita, her healer and companion, fell prey to this. But none of the women ever told her she was too angry. And when she fought for them, when she avenged them, the men did not think her too angry then. What I loved about this book was the subversion of that trope, that Angry Black Woman trope that is so often used to discredit the work marginalized women of color do. Onyesonwu locates the source of her anger here:

Humiliation and confusion were the staples of my childhood. Is it a wonder that anger was never far behind?

And then her mentor’s mentor, a man who intially underestimates her and tries to turn her away, validates the usefulness and power of that anger here at the close of the book:

Onyesonwu’s very essence was change and defiance.

Anger is an active emotion. It drives things, it pushes things. It can be abusive, and it can do wrong, but it can be a force for justice, too. Onyesonwu struggles with this in the book. Much of the book has her shaking people into righteous anger, fueling it, leaning into it and seeing it as a strength. And I loved the book for that.

Okorafor as an author also spends much of the narrative outlining how prophecies create their own ends. If you decide that Ewu people are inherently violent, and then you shun them and teach them they are evil and cast them out and leave them no choices but to turn criminal in desperation, then yes, she argues, you may see them resort to violence. If you cast spells on young women to make sexual arousal before marriage deeply painful and the spell only breaks with marriage then yes, the women of a given tribe might have a very peculiar relationship to sex and their husbands. And if you are a sorcerer and part of initiation is living through your death years before it occurs, what must that do to you? You carry it with you, you know when it happens, you dream of it—could you change your fate if the time came? Would you want to? Or, having resigned yourself to it so long ago, do you simply play the part? Even at the end, even defiant and angry Onyesonwu who does not fear death, even she submits to her own death.

All in all, I felt the pacing could have been tighter, and there are ticks of Okorafor’s writing I don’t particularly like, but the worldbuilding is so acute and profound and the scope and brutality of the questions she asks with her writing are so pressing that I don’t care. And for other readers? She will be stylistically perfect. Your mileage may vary, but likely this is a book well worth reading either way.

January 17, 2015

Book Review: THE DAYLIGHT GATE

Witchery popery popery witchery

Under the paranoid reign of James I, witches and Catholics are hunted across the English countryside. Lancashire in particular is a suspected home to both populations. Jeanette Winterson’s THE DAYLIGHT GATE takes a historical instance—the first documented witch trial in English history—and spins around it a tale of what might have happened. The story unfolds from multiple perspectives: from the witches’ viewpoints, from the viewpoints of those who hunt them, from the viewpoints of those who try not to involve themselves but who cannot help but get drawn in.

THE DAYLIGHT GATE is a small, feral book. It is prose, but reads like poetry. It is set in England, but the northern England of 1612 is a land so far removed and the lives of the people there so different that it is intoxicating. It is beautiful and horrific at once, and it revels in that dichotomy.

The book is ultimately about liminalities—the title refers to the witching hour, twilight, the time where day and night dangerously blend together. The narrative shuffles around in time and space, bats back and forth between points of view, and is anchored really by a single character: Alice Nutter. Alice, herself, is a study in liminality: a woman born poor who makes her own fortune and therefore knows both wealth and suffering. A woman who loves both women and men. A woman who was married once—just once—but who has her own land and her own possessions. Alice is perceived as dangerous, as redemptive, as powerful, as impotent depending on who you ask. But she is always on the outskirts.

‘You are stubborn,’ said Roger Nowell. ‘I am not tame,’ said Alice Nutter.

The book hinges on Alice’s choices, on Alice’s will and strength. Alice’s ability to choose depends on her willingness to walk the fine line between states—between polite society and rebelliousness, between femininity and masculinity, etc. She has secrets, and she has moments of startling frankness. She has her undoings, but some of the are of her own accord and some of them are not. It is a mark of Winterson’s talent that Alice, as a character, grows in complexity in the span of such a short book. Actually, quite a few characters do—a priest/terrorist has a crisis of conscience, the afore-quoted Roger Nowell turns out to be a much more layered and decent man than he seems to be at first, and one character in particular has evolutions on evolutions I did not expect.

This is a book, at its heart, that is deeply feminist. Virtually all books written by women about witch trials are. What Winterson brings to the forefront here is the terror and the beauty of the liminal state, the power of between-ness. What is a witch but a woman with power she’s not supposed to have? What is that but something in-between: a feminine-masculine thing? It scares us because it’s slippery, hard to define, because it might just turn into a hare and escape a trap, run into the forest and out of sight. This is old ground Winterson is treading, yes, but it’s important ground to tread and she treads it well, with aplomb, with a spring in her step and a glint in her eye.

January 14, 2015

Book Review: HYSTERICAL: ANNA FREUD’S STORY

HYSTERICAL: ANNA FREUD’S STORY, by Rebecca Coffey, is an historical novel told from the perspective of Anna Freud. It is a memoir Anna writes on her deathbed, and in true Freudian fashion as Anna reflects back on her life—the choices she made, the actions which defined her, how she came to be who she was—much of her memoir centers on her childhood. And much of her childhood ruminations center on her relationship with her monstrously overshadowing father, Sigmund Freud.

In the Author’s Note of the book, Rebecca Coffey, a journalist by training, mentions that she did not set out to write a novel. When the various estates and Freudian strongholds kept Anna Freud’s personal letters and writings under lock and key, Coffey turned to fiction to fill in the blank spaces. This, I think, is an admirable approach—Anna’s is a voice that deserves to be heard. Anna was a lesbian, but her father’s work denounced her sexuality. At the same time, Anna Freud, of all of Freud’s children, was his clear intellectual heir and also his caretaker in his old age. They had a close professional and emotional relationship, but how did those theories about Anna’s “brokenness” affect her? Despite his warnings about the inherently erotic nature of the analytic relationship, Freud analyzed Anna, probably about her sexuality—what must that have done to their relationship? These are the questions Coffey sought to explore with her novel, and they are good ones. They are ripe for exploration. I was chomping at the bit to read this book.

This is a situation, ultimately, of unfulfilled promise. When Coffey allows Anna to delve into the questions above, it is only with glancing blows. The story behind the book—Coffey’s search for answers, the tired old Freudian vanguard circling the wagons and shutting her out, her turning to fiction to create answers for herself—is more intriguing than the book itself, which is a great pity.

For the book to work, Anna has to shine. As a narrator, for us as readers to carry with her, I feel the book could have gone one of two ways: she could have been blisteringly honest, terrifyingly honest about everything. There would have been anger, and evisceration, and confusion. A lot of emotion. A lot more emotion than she displays in the book as Coffey wrote it. Or, Anna could have been inherently unreliable—equivocating, hero-worshiping, lauding Sigmund in ways that betray to the reader that perhaps not all was what it seemed. Instead, we got an Anna who was removed and distant, smirking and gentle. It seemed it wasn’t her own story she was even telling.

The rhythm of the narrative was strange; so much focus on some episodes of her life and so little focus on others. This is, perhaps, an odd complaint to make here, but I would have preferred the book to be less psychoanalytically focused—I would have liked fewer exhaustive sessions of Anna detailing her weird dreams to her father and more scenes of her actively living her own life. I wanted to see and feel her actually fall in love with the women in her life and experience her grappling with what that meant—not in sessions with her father, but in her own mind and in her skin. Ultimately, given the tightness of the focus on the analysis sessions with Sigmund, and given the narrowing in on his homophobia, the book became more about Anna’s inability to save him from himself than about her thoughts or her life or her actions.

As a novel, the book suffered from a lack of characterization and flawed pacing. To succeed, Anna’s voice needed to be strong enough to carry the book, but Coffey never found it—Anna drifted into the background, and as in history, she was overshadowed once again by her larger-than-life father here. I applaud the intent of this work, but the execution left much to be desired for me.