Steve Bull's Blog, page 2

August 29, 2025

Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CCXI–A ‘Great Simplification’ Is On Our Doorstep, Redux

A couple of months ago, I penned an article summarising a handful of resources that had helped to inform and guide my thinking on our various predicaments. Those five resources were just a sampling of the ones I’ve been exposed to over the years. During my initial exposure to the concept of peak oil and its implications for societal collapse, I devoured numerous resources as I struggled to understand the information and process the arguments being made.

Below you will find another half dozen summaries of additional resources I reviewed with an attempt to combine their arguments into a coherent ‘conclusion’ about what they suggest for humanity’s future….which is not unlike that reached in the first post. (see: Website Medium Substack)

Collapse

The 2009 documentary, Collapse, features the late Michael Ruppert and was the driving force for my journey into the rabbit hole of peak oil and a revisiting and deeper look into the idea of societal ‘collapse–I bought and read Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse Of Complex Societies not long after viewing the documentary.

I was somewhat aware of the notion of societal decline, having pursued an undergraduate degree and Master of Arts in anthropology (focussing mostly on North American archaeology; working on archaeological digs in Ontario, Canada, and near Oaxaca, Mexico), but never truly read much on it or its wider implications while a student–except for reading Bruce Trigger’s Times and Traditions: Essays In Archaeological Interpretation that, amongst other things, explored the notion of cultural continuity over time (I worked for/with and learned from two of his graduate students–one that remained in academia, Dr. David G. Smith). And I had never heard the term ‘Peak Oil’ prior to watching this documentary.

One fateful Friday evening in late 2010, on a family outing to our local Blockbuster to pick up some videotapes for weekend viewing, I came across Collapse and it sounded interesting. So, I rented it to watch sometime in the next few days–along with some others (probably a Pixar movie or two given the age of my daughters at the time), likely the latest Toy Story or The Incredibles.

The documentary is basically an extended interview with Michael Ruppert, a Los Angeles narcotics detective turned whistleblower, journalist, and author. While the director of the film was seeking Ruppert out to follow-up on his accusations about high-level drug smuggling by the CIA, he found Ruppert had become far more interested in the concept of Peak Oil, our debt-based and financialised economic system, government and corporate malfeasance, environmental degradation, and the implications of all of these for industrial civilisation and its sustainability.

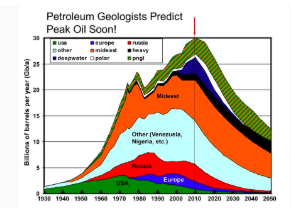

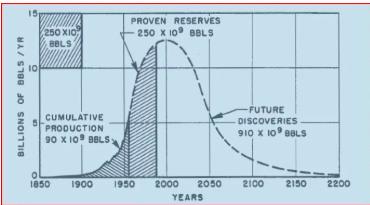

forbes.comThe primary concern raised by Ruppert in the documentary is the peak of hydrocarbon resources, particularly oil. He argues that it is a key tipping point for societal collapse given the importance of this resource for maintaining virtually every complex system in modern societies–particularly manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture. He also stresses that oil is vital for sustaining the growth that underpins our monetary systems and financialised economies. He asserts that the decline of cheap, abundant oil means the decline of the energy available to keep our modern, global-industrial societies functioning, and certainly not growing as they have.

Ruppert goes on to argue that the much ballyhooed and trumpeted alternatives (i.e., nuclear, solar, biofuels, wind, hydrogen) cannot replace oil’s density nor its scale, being distractions or worse (i.e., scams). He is also highly critical of the Ponzi-type structure of our debt-based financial system and its dependence upon infinite growth on a finite planet. He argues that this is an entirely unsustainable system and is set up for a catastrophic collapse at some point.

Ruppert also points out that there is an awareness of the above converging crises by the world’s governments and corporations, and that they are covering them up in order to suppress dissent and maintain status quo economic and power structures. It was Ruppert’s growing awareness and investigations into CIA drug trafficking that opened his eyes to the systemic corruption prevalent in government and eventually led him to appreciating how important energy resources are to supporting industrial civilisation–a significant amount of government policy and action has been oriented towards securing and controlling energy (i.e., oil) reserves, regardless of the ‘costs’.

Ruppert highlights the undeniable fact that humanity has entered ecological overshoot by living far beyond the planet’s natural environmental carrying capacity through its consumption of resources in a manner significantly faster than they can be replenished. His contention is that modern, industrial civilisation founded upon cheap oil (and other hydrocarbons) and with a completely unsustainable economic system is on the precipice of ‘collapse’ with no ‘solutions’ to this predicament.

You can view this documentary here.

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality

Ecologist Richard Heinberg’s 2011 text asserts that the exponential economic growth that has been present since the Industrial Revolution has basically ended due to fundamental biogeophysical limits. This, he argues, is a permanent decline and not a temporary phenomenon.

He posits that this cessation is due to: energy constraints (particularly easy- and cheap-to-access hydrocarbons); ecological systems degradation (most planetary boundaries have been breached–especially with respect to resource scarcity, biodiversity loss, pollution, and climate); and, economic instability (due to its debt-based foundation and the need for perpetual growth to sustain it).

resilience.orgHeinberg further challenges the concept of growth being synonymous with prosperity, stressing that the negative social and environmental costs are typically ignored. He contends that the growth imperative that societies pursue is completely unsustainable on a finite planet, and that the depletion of resources and falling net energy are limits that economic analyses overlook. He also argues that the technology and economic ‘solutions’ typically chased can only provide temporary relief, being unable to replace hydrocarbons at scale or energy density.

He believes that there is no immediate threat but that the growth we have known has ended and we have a choice to make between unmanaged ‘collapse’ and ‘managed’ decline towards a ‘steady-state’ economy that exists within ecological boundaries.

The components of his proposed response with respect to managing societal ‘degrowth’ include, in no particular order, efforts to: stabilise population growth in order to reduce increasing demand and stress on the planet; reduce consumption and waste, thereby conserving resources; relocalise economies to reduce dependence upon fragile, long-distance supply chains; abandon our debt-based monetary system and its dependence upon perpetual growth, and restructure/write-down current, unpayable debts; rapiding scale up ‘renewable’ energy sources; and, encourage sufficiency, sustainability, and community, while discouraging material accumulation.

Heinberg’s contention is that the 2008 financial crisis was not a one-off, isolated event but a symptom of deeper systemic limits to growth, and stresses the consequences of energy depletion on the financial system. He suggests that fundamental change to the system is necessary given the long-term prospects of continuing the growth imperative.

Basically, Heinberg presents the argument that the global economy has encountered a limit with significant headwinds caused by debt saturation, resource depletion, and environmental degradation. He concludes that disaster is guaranteed if we continue with the growth paradigm and that the best path forward is a conscious transition towards resilient communities and an ecologically-sustainable economy.

The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future Of Our Economy, Energy, And Environment

Chris Martenson’s The Crash Course (2011) suggests that the next twenty years are going to be very different from the past twenty as three converging crises (i.e., energy, economy, environment) are increasingly impacting humanity and its modern societies. Martenson argues that our various systems are unsustainable and set up for a ‘crash/collapse’, primarily due to our exponential growth (population and economic) bumping into the biogeophysical limits of a finite planet.

The most fundamental issue, according to Martenson, is humanity’s poor understanding of the exponential function and our pursuit of growth. This is especially true as it pertains to population, debt, resource consumption, and the impacts of these on the environment. While things can appear stable for a long period of time, exponential growth results in dramatic, sudden consequences.

shutterstock.comOf primary importance are the interlocking crises of the three Es: economy, energy, and the environment.

The current world economy has been founded upon ever-increasing debt (particularly since the gold-standard was abandoned) with a money system requiring continuous growth to avoid collapse. Massive unfunded liabilities are present (that likely won’t be met) along with destabilising inequality.

Our current societies depend upon energy for all its complex systems, particularly that derived from hydrocarbons. We have enjoyed more than a century of cheap, high-quality, and abundant hydrocarbons (especially oil) to build modernity, but that time has passed with the more expensive, more difficult to extract, and lower EROEI (energy-return-on-energy-invested) hydrocarbons now dominant. Given our dependency on this resource (and alternative’s inability to scale up, their intermittency, and increasing mineral/material challenges), the growth needed to keep our complexities functioning is at risk.

Not only is the exponential growth humanity is pursuing colliding with resource limits, but climate change has become a major threat along with pollution and degradation of our environment. These things are putting the planet’s ability to support human economic activity and all life at risk.

Martenson emphasises that these crises are interrelated in a complex manner with economic growth requiring energy, but the extraction and use of energy is resulting in ecological systems disruption and collapse. This environmental harm negatively impacts the economy with increasing amounts of energy necessary to mitigate the negative consequences. But debt-based money needs growth, requiring even more resources and energy–a very problematic feedback loop.

This pursuit of perpetual growth on a planet with finite resources is impossible and so the system will change, regardless of our wishes to sustain it. This ‘crash’ is a process, not an event, and will result in a lower-throughput world. We are likely to experience a long period of economic contraction, resource scarcity, environmental instability, and social disruptions.

Martenson offers some means of adapting on various levels. On a personal level, he suggests getting out of debt and putting any savings in tangible assets, learning some practical skills, and building local connections. For communities, he believes that they should build local food systems and economic networks, and create local energy production. Finally, on a societal level, he argues that there should be a proactive transition towards true sustainability. In particular, Martenson includes an entire chapter (What Should I Do?) on actionable advice, such as preparedness, personal finance, and community building.

This text outlines the systemic risks for modernity, highlighting the interlocking complexity of the environment, economy, and energy, and why the pursuit of perpetual growth on a finite planet is a dangerous myth. As a result, Martension stresses that humanity should begin immediate preparation by way of adopting adaptive strategies that provide communities with resilience.

You can access the video series of this text here.

The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Crises of the Twenty-First Century

James Howard Kunstler’s The Long Emergency (2005) presents the case that our modern world, built upon relatively inexpensive hydrocarbons (particularly oil), has begun an era of building crises and contraction. As a result of ‘Peak Oil’ a decades-long period of resource scarcity, economic contraction, social disruptions, and environmental degradation is upon us. This will result in the eventual collapse of modernity’s complex systems and a return to localised, agrarian communities.

Of particular importance to these crises is Peak Oil–the peak of the easy-to-access conventional oil is the ultimate catalyst to our predicament. With its portability, energy-denseness, and importance to virtually everything in our societies (especially agriculture, transportation, and manufacturing), its decline equals the contraction of human economies and interconnectedness.

The failure of ‘renewables’ to be able to be scaled up in time or be as effective to alleviate the eventual depletion of oil puts the continuation of modernity at significant risk. This risk is being exacerbated by a changing climate that is contributing to drought, floods, agricultural disruptions, and infrastructure damage and destruction.

But even with ‘renewables’, the issue of resource depletion is becoming problematic with shortages of fresh water, fish, topsoil, and various important minerals. On top of these issues is the rise of infectious disease and the likelihood of pandemics that can result in population displacement, antibiotic resistance, supply chain disruptions, etc..

As these predicaments combine to add increasing stress to our world, we are witnessing growing economic and political instability. Kunstler predicts the failure of centralised governments and our globalised and financialised economic systems as a result of this, leading to increased authoritarianism, international and domestic fragmentation, and conflict.

He further suggests that our world will soon witness the: ‘collapse of suburbia’ (“the greatest misallocation of resources in history”) due to its significant dependence upon cheap oil (e.g., cars and trucks), lack of local resources, and inefficient land use; end of globalisation as complex and fragile long-distance supply chains falter, alongside the growth of localised/regional economies; contraction of our finance-based and growth-dependent global economies; decline of populations because of famine, disease, and conflict; sociopolitical stress and extremism, accompanied by social unrest, mass migrations, and rising conflict over resources due to shortages; rise of ‘Agrarian Localism’ signalled by labour-intensive farming communities where skills and knowledge in farming, carpentry, and small engines will be vital to community survival. All of this will lead to geographic-based winners and losers where areas with potable water, fertile soil, and navigable waterways will fare much better than those without.

The book is a warning that the abundance of modernity (at least for some in so-called advanced economies) is approaching an end with the waning of inexpensive oil. Kunstler predicts an at-times chaotic restructuring of human societies and calls for a recognition of the ever-present risks of our globalised, industrial-based world and for building community-level resilience.

The Long Descent: A User’s Guide to the End of the Industrial Age

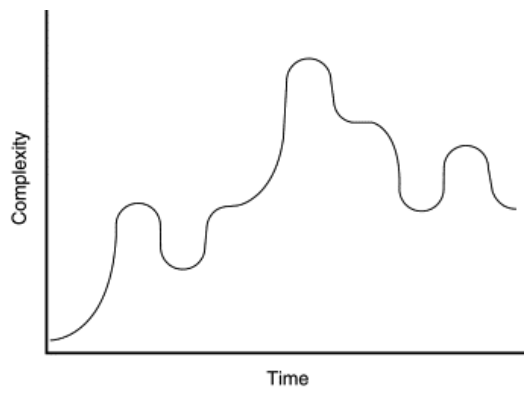

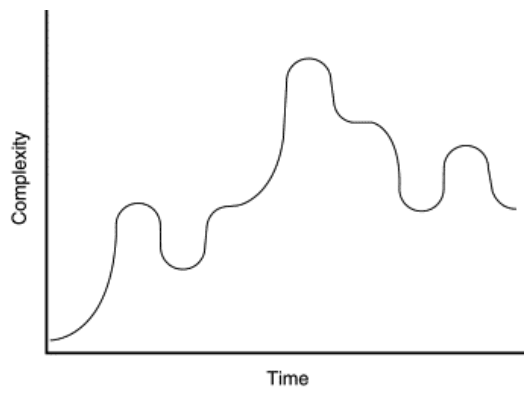

John Michael Greer’s 2008 text presents the case that industrial civilisation’s simplification will be a rather long and uneven decline by way of what he terms ‘Catabolic Collapse’. There will be long periods of stability with relatively shorter periods of crisis—a staircase-type descent over generations towards a deindustrialised future.

The idea of ‘catabolic collapse’ is based on the notion that a society will consume its capital (e.g., infrastructure, social complexity) to meet the needs that erupt during a crisis, similar to an organism cannibalising its body for energy when starving. When a crisis arises, such as an economic depression, breakdown and loss occurs but stabilisation at a lower level of complexity eventually takes place based upon use of ‘resources’ from the previous, higher level. This ‘cycle’ occurs periodically over decades/centuries leading to a much simplified society/civilisation with variability depending upon local context.

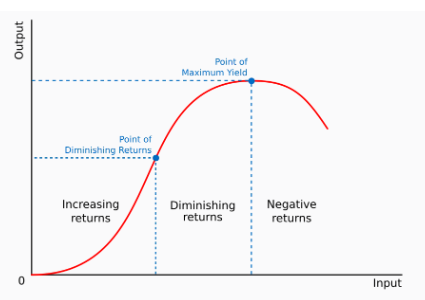

The impossibility of pursuing perpetual growth on a finite planet combined with diminishing returns on investments in complexity are the prime causes of ‘collapse’. Resource depletion (especially of oil), environmental damage, and economic instability have led to this irreversible predicament with the rate of decline and the challenges encountered varying widely depending upon regional context and the resources available.

Greer stresses that there will be significant sociocultural and psychological challenges to this descent, especially as it pertains to beliefs in progress and privilege. He is quite critical of the blind faith most have regarding technology and its ability to ‘save’ humanity from this predicament, especially because they all depend upon the resources that are quickly depleting and/or they almost always create new issues/problems.

Greer’s advice for addressing the issues is for individuals and communities to try and avoid the denial of this reality and build local resilience via practical skill development (e.g., traditional crafts, gardening, basic healthcare, etc.) to reduce as much as possible reliance upon the complexities of modern societies. He sees the attempts to save our industrialised societies as futile and argues that we would be better to learn how to repurpose equipment and preserve valuable knowledge and skills that will serve regions in a de-industrialised world.

Greer’s perspective is based upon pre/historical examples of ‘collapse’, ecology, and systems thinking. It focuses upon practical adaptation rather than attempts to maintain the unsustainable, arguing that the future will not be characterised by either the utopian nor apocalyptic predictions. The future will be one of a lengthy, descending staircase due to ecological limits and resource depletion. Its multi-generational descent affords the opportunity to those willing to accept its inevitability the time to prepare for a more localised and hopefully sustainable future.

[See: Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CXXXV–Collapse Now To Avoid The Rush: Our Long Emergency. Website Medium Substack]

The End of Growth: Adapting to a New Reality of Expensive Oil and Slower Growth

Economist Jeff Rubin’s 2012 text argues that high, sustained oil prices (due to geopolitical instability and scarcity) have brought an end to the ongoing economic growth of the past century. These high oil prices act as a ‘tax’ by increasing production costs across all sectors and typically trigger recessions. Rubin predicts that a permanent high price could prevent a robust recovery towards previous growth rates.

Moreover, inexpensive transportation fuels are what has aided the growth of globalisation, long-distance supply chains, and just-in-time delivery/inventory systems; higher prices put these all at risk. We should expect a relocalisation of production as a result; alongside more expensive consumer products.

Unconventional oil resources (i.e., shale and bitumen/tar sands) are not the saviours they are being touted as since they are far more expensive to extract. They will not bring lower costs back, nor result in the surplus net energy that sustains growth. Alternatives such as complex wind and solar technologies are also not helpful since they are expensive and cannot scale up rapidly. These ‘renewables’ require massive investments that are more difficult to make in an era of low growth and high debt.

Rubin argues that recessions and the debt crises and austerity that tend to follow are the symptoms of expensive energy and not the cause. The fallout from increasing energy prices are feedbacks that further depress demand and result in slower or stagnant economic growth and price inflation (i.e., stagflation).

With higher energy prices, we are likely to experience what Rubin terms ‘stagflation lite’ characterised by much slower growth and persistent price inflation. Central banks that are charged with stimulating growth (usually via attempts to reduce interest rates) while fighting price inflation (usually via attempts to increase interest rates) are caught in a dilemma.

Rubin predicts that consumers in ‘developed’ economies will experience a decline in their consumption due to price inflation caused by higher energy prices. There will also be a continued shrinking of the ‘middle’ class, and reduced trade deficits and volume for these economies. He further believes that expensive fuels will reduce long-distance commuting, making suburban communities less attractive and leading to a revitalisation of urban centres. There will also likely be a resurgence of local and regional goods production, especially of food.

As an economist, Rubin focuses mostly upon the price of oil and its knock-on impacts. He holds that this is the most important aspect and not resource depletion per se. He notes the historical connection between recessions and oil price spikes. Rubin considers the end of growth as an economic inevitability driven by market forces but not necessarily resulting in ‘collapse’.

Basically, he argues that the era of relatively cheap oil has ended and with it the end of the robust growth developed economies have experienced for decades. The hyper-globalisation characterised by this time will reverse and a relocalisation of goods production will ensue. This transition will see slower growth, higher prices, and a lower standard of living, particularly in terms of material goods.

These resources come to a relatively common conclusion: over the coming decades modern human societies will experience an inevitable transformation due to fundamental constraints and significant challenges.

Primary among their messages is that the growth human societies have experienced for some centuries (and especially the past two, thanks to cheap and abundant hydrocarbons) is approaching an inescapable end. Environmental degradation, the limits imposed by finite resources, and an unsustainable debt-based financial system have combined to bring a rather abrupt halt to the ongoing growth of humanity, particularly its population and economies. Founded upon the idea of perpetual growth, modern complex societies cannot continue on their current trajectory. A significant reduction in material throughput is guaranteed which can’t help but lead to economic stagnation/collapse.

The primary reason for all of this is that the relatively dense energy resource that has been easy-to-access and cheap-to-extract/-distribute–and enabled modernity (in the sense of industrialisation and massive, globalised energy-averaging systems)–has encountered significant diminishing returns. The consequence of this is that less and less net energy is available as time passes, and is made worse by our growth momentum. While some argue that alternative energy sources are important to pursue, they admit that they are insufficient to maintain societal complexity.

Given the above, it seems certain that the future of human societies will be one with far less energy available leading to far less complexity. This means the contraction and eventual loss of most long-distance supply chains, with more localised production of goods. The organisational and technological complexity of modernity will also contract and simplify, meaning less bureaucracy and much greater reliance on local knowledge/skills, manual labour, and simpler tools. Regions with ample local resources (especially water and arable lands) may fare relatively well but large urban centres that depend upon the inflow of resources will very likely struggle.

It’s important to note that while there may be very turbulent periods during this inevitable contraction, most authors contend that the coming simplification will be relatively gradual. ‘Collapse’ will not likely be ‘sudden’ but will be prolonged with periods of crises as well as periods of relative stability, and perhaps even some ‘recovery’ to a higher level of complexity–at least for a short time before continuing its simplification.

The consequences of the coming simplification will probably be uneven for regions, communities, and social classes. Much will depend upon local resources, infrastructure, leadership, and social cohesion. There is likely to be much turmoil, instability, and conflict. Societies are likely to experience resource conflict, political uncertainty, economic recession/depression, social discontent, and quite possibly violence. Many also suggest that climate change will act as a ‘threat multiplier’.

Overall, these individuals contend that extinction is not the likely outcome but a radical transformation of our global, industrialised societies is since these are quite unsustainable. The inevitable simplification/descent/collapse/decline of complex societies will likely experience bouts of drastic disruption and conflict, as well as severe hardships and increasing vulnerability to shocks (e.g., political, economic). Community/regional resilience via social cohesion, practical skills, local resources, etc., will aid in adapting to changes as they occur over decades/generations.

While the future is certainly uncertain, prospects strongly suggest it will be one of less complexity and energy, and one of increasing localisation. The speed of energy decline, climate impacts, and adaptive effectiveness will determine the path and severity of the trajectory for most.

Prepare accordingly.

What is going to be my standard WARNING/ADVICE going forward and that I have reiterated in various ways before this:

“Only time will tell how this all unfolds but there’s nothing wrong with preparing for the worst by ‘collapsing now to avoid the rush’ and pursuing self-sufficiency. By this I mean removing as many dependencies on the Matrix as is possible and making do, locally. And if one can do this without negative impacts upon our fragile ecosystems or do so while creating more resilient ecosystems, all the better.

Building community (maybe even just household) resilience to as high a level as possible seems prudent given the uncertainties of an unpredictable future. There’s no guarantee it will ensure ‘recovery’ after a significant societal stressor/shock but it should increase the probability of it and that, perhaps, is all we can ‘hope’ for from its pursuit.”

If you have arrived here and get something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website or the link below — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers).

Attempting a new payment system as I am contemplating shutting down my site in the future (given the ever-increasing costs to keep it running).

If you are interested in purchasing any of the 3 books individually or the trilogy, please try the link below indicating which book(s) you are purchasing.

Costs (Canadian dollars):

Book 1: $2.99

Book 2: $3.89

Book 3: $3.89

Trilogy: $9.99

Feel free to throw in a ‘tip’ on top of the base cost if you wish; perhaps by paying in U.S. dollars instead of Canadian. Every few cents/dollars helps…

https://paypal.me/olduvaitrilogy?country.x=CA&locale.x=en_US

If you do not hear from me within 48 hours or you are having trouble with the system, please email me: olduvaitrilogy@gmail.com.

You can also find a variety of resources, particularly my summary notes for a handful of texts, especially William Catton’s Overshoot and Joseph Tainter’s Collapse of Complex Societies: see here.

August 28, 2025

Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CV–That Uncertain Road, Part 2

March 6, 2023 (original posting date)

Teotihuacan, Mexico. (1988) Photo by author.

Teotihuacan, Mexico. (1988) Photo by author.That Uncertain Road, Part 2

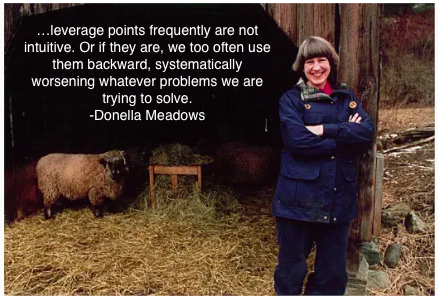

The set of possible futures includes a great variety of paths. There may be abrupt collapse; it is also possible there may be a smooth transition to sustainability. But the possible futures do not include indefinite growth in physical throughputs. This is not an option on a finite planet. The only real choices are to bring the throughputs that support human activities down to sustainable levels through human choice, human technology, and human organization, or to let nature force the decision through lack of food, energy, or materials, or through an increasingly unhealthy environment.

– Donella Meadows, Jorgen Randers, Dennis Meadows (2002) Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update

However much we like to think of ourselves as something special in world history, in fact industrial societies are subject to the same principles that caused earlier societies to collapse. If civilization collapses again, it will be from failure to take advantage of the current reprieve, a reprieve both detrimental and essential to our anticipated future.

-Joseph Tainter (1988) The Collapse of Complex Societies

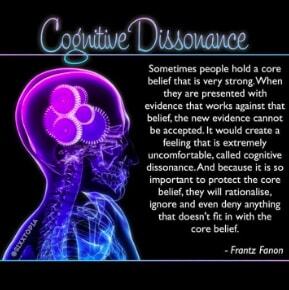

In Part 1, I argue that humans react quite negatively to uncertainty and as a result leverage their tool-making skills in attempts to control their environment and depend upon their story-telling abilities to create belief systems that support the idea that they can reduce or even eliminate the unpredictability of the future and thus reduce anxiety-provoking thoughts.

Despite being unable to eliminate such uncertainty, I propose a possible roadmap to our future based upon the beliefs that we live upon a world with finite resources and that there exist biological and pre/historical precedents to aid our understanding of what may befall us.

The most important biological precedent may be that of ecological overshoot while the pre/historical one is possibly the recurring rise and fall of societal complexity that is expanded upon below.

Precedents from our past

Pre/historically homo sapiens have experimented dozens of times over the past 10,000–12,000 years in developing and attempting to sustain large, complex societies. Every iteration to date has eventually ‘failed’. Every. One.

The following is a sampling of some of the largest complex societies (aka civilisations/empires/states) that have existed in our past, showing their rather brief stay upon our planet:

The decline/fall/collapse that has been noted in every one of our attempts at large, complex societies to date may take a relatively long time — in human terms — but it has always happened, eventually. The fall of the Roman Empire appears to have taken centuries[1]; that on Easter Island perhaps only a handful of decades[2]. These experiments suggest very strongly that ours too will follow this trajectory. No guarantees of course but the evidence is overwhelming.

And while history does not repeat itself, as the saying goes, it does rhyme with many components of a society’s decline experienced again and again according to the archaeological and historical records.

Perhaps this is because we are ‘hard-wired’ in certain ways to respond within a narrow range of re/actions. For example, many if not most of our behavioural responses to any situation are connected to a flight-or-flight one (aka acute stress response)[3] and or avoidance of pain/seeking of pleasure one (aka pleasure principle)[4]. These are deep-seated physiological responses that exist in virtually every animal but have significant emotional-cognitive repercussions for homo sapiens, affecting our sense of control.

It could even be as straightforward as archaeologist Joseph Tainter argues in The Collapse of Complex Societies: a complex society in its ongoing problem-solving efforts encounters diminishing returns on its investments in complexity eventually leading participants to withdraw their support as the costs of participation outweigh the benefits, with societal breakdown ensuing as the organisational structures that hold things together disintegrate[5]. Much like boiling a frog, the shifts that accompany such a decline are not necessarily noticeable immediately or within the temporal context of a standard human generation (about 20–25 years). Normalcy bias causes us to interpret events not as sudden historical changes, but as the typical ebb and flow of life.

Regardless of why complex society after complex society follows this recurring pattern of a rise in complexity followed by a loss of it, with just the length of time of a society’s existence varying, I believe it’s informative to consider what the evidence suggests with respect to what societal complexity is exactly and how it tends to arise since this may better inform us on what might be lost (or simplify) as decline for our version of it proceeds.

What is societal complexity?

It’s important to have a good grip on what societal complexity is since when push comes to shove this is what is going to be ‘lost’ as our various systems begin to breakdown.

Archaeology suggests the following with respect to the growth of complexity, with complexity referring to the size, distinctiveness and number of parts, variety of social roles, distinctiveness of social personalities, and variety of mechanisms to organise parts into a whole[6].

First, we need to understand that the complex societies of the past 10,000 or so years are an anomaly in human history with autonomous, self-sufficient local communities being the norm (approximately 99.8% of human existence). Large, hierarchical complex states have only been around the past 6000 years or so, but once established, expanded and dominated.

Anthropological studies suggest ‘simpler’ societies are indeed smaller (from a handful to a few thousand individuals) than ‘complex’ ones, but they still have displayed great variation in size, complexity, ranking, and economic differentiation. They tend to be organized upon kinship relations with leadership being minimal (based upon personality, charisma, and persuasion) and without privilege or coercive power; it is also usually restricted to special circumstances. Equitable access to resources is the norm and wealth accumulation is not. Where political ambition exists, it is channeled towards public good and any acquisition of excess resources is redistributed, bringing greater social status[7].

Where more complex political differentiation arises, permanent positions of authority/rank can exist in an ‘office’ that can be hereditary in nature. As a result, inequality becomes more pervasive. Such groups tend to be larger and more densely populated. Political organisation is larger, extending beyond the local community. A political economy arises with rank having authority to direct labour and economic surpluses. And with greater size comes a need for more social organisation that is less dependent upon the kinship relations that constrained individual political ambitions.

Why did complex societal complexity arise?

There are two basic schools of thought on why societal complexity arose: conflict and integration.

The conflict-based school of thought suggests that the institutions that govern a large complex society arose as coercive mechanisms to try and resolve intrasocietal conflict that were an epiphenomenon of economic stratification. Basically, the sociopolitical system developed to maintain the ruling class’s privileged positions that came with their control of the resources and how they were distributed amongst the masses[8].

Those who support the integration-based school argue that complexity arose because of social needs such as shared social interests, common advantages, and consensus. The sociopolitical system from this perspective is a positive response to the stresses affecting human populations. The differential rewards that accrue to certain members of society is the cost for the benefits of the centralisation and stratification that develops[9].

Both of these schools of thought have pros and cons, but what they appear to have in common is that they acknowledge the role of legitimising activities (some of which must include real, material outputs), symbolic manipulation, and coercive sanctions. They also both appear to see the state as a problem-solving organization that arose out of changed circumstances[10].

In summary, a complex society is a problem-solving organisation — what some refer to as an adaptive system[11] — that gives rise to increasing complexity (in terms of more parts, differing parts, greater differentiation and inequality, increased centralisation and control) as circumstances need. They are anomalous in human history but have dominated since they began forming about 6000 years ago.

What is collapse for a complex society?

As with any proposal, defining the fundamental term is important to ensure mutual understanding. This is particularly so for the term ‘collapse’ given the negative connotations that so often come with it.

For my purposes I defer to archaeologist Joseph Tainter on this topic who suggests in The Collapse of Complex Societies, “Collapse…is a political process. It may, and often does, have consequences in such areas as economics, art, and literature, but it is fundamentally a matter of the sociopolitical sphere. A society has collapsed when it displays a rapid, significant loss of an established level of sociopolitical complexity.” (p. 4)

‘Collapse’ then is a loss of sociopolitical complexity that has knock-on impacts upon the other complex systems that exist in a human society. A sociopolitical system could be considered the linchpin or foundation of the organisational structures that arise as complexity increases; a centralising phenomenon that coordinates, for better or worse, the redistribution of goods and services in large human groupings.

While sociopolitics is certainly not everything to the existence of human complex societies, it would appear to be of overarching importance. It seems to be an epiphenomena of the organisational requirements that accompany larger settlement groups in their problem-solving efforts.

Below I will elaborate more fully on how this simplification has played out in the past and thus how it is more than likely to do so in the future.

Societal Simplification

Pre/historical examples of ‘collapse’ have been found to have experienced a rapid, significant decline in complexity where society is smaller, less differentiated/heterogeneous, less specialized, and has less control over individual behaviour. In addition, surpluses are smaller and the benefits for participants are less — but so too are the costs. It has been found to be a continuous variable much as its emergence is and can be a drop within a level or between them (i.e. state to chiefdom)

If we agree with Tainter’s definition outlined above, then one needs to keep one’s eye on the sociopolitical realm and its shifting manifestation as time passes. The following is where we need to pay particular attention according to the pre/historical records for as Tainter’s thesis posits ‘collapse’ manifests itself as:

“a lower degree of stratification and social differentiation;

less economic and occupational specialization, of individuals, groups, and territories;

less centralized control; that is, less regulation and integration of diverse economic and political groups by elites;

less behavioral control and regimentation;

less investment in the epiphenomena of complexity, those elements that define the concept of ‘civilization’: monumental architecture, artistic and literary achievements, and the like;

less flow of information between individuals, between political and economic groups, and between center and its periphery;

less sharing, trading, and redistribution of resources;

less overall coordination and organization of individuals and groups;

a smaller territory within a single political unit.” (p. 4)

Simple societies through empires can experience these changes in complexity, including ‘collapse-level’ shifts. It has not only been a recurring process throughout pre/history but it has taken place across the planet. Basically, the above reflects a loss of complexity, or in the words of Nate Hagens, a Great Simplification[12].

Perhaps most significantly is the loss of centralised control and authority. The sociopolitical centre can be seen to weaken as more distant regions breakaway and revolts become more common. Government revenue declines but is ‘countered’ through currency devaluation that results in price inflation for the masses. Foreign challengers begin to experience greater success with this exacerbated by lower revenues for the military. As the elite attempt to mobilise resources to meet the challenges, the people become less supportive and more restive — and a positive feedback loop can ensue where the increasing displeasure displayed by the masses is countered by greater authoritarianism by the elite, which then leads to even more pushback by the people leading to increasing attempts at control by the ruling caste.

As sociopolitical power of the elite begins to weaken and the masses become increasingly disenchanted, they oftentimes destroy the political centre by ransacking it resulting in a loss of control over the previously unified region. Consequently, smaller sociopolitical states emerge but then engage in power conflicts with each other and may experience several years of ongoing disputes/war.

Any security that was provided by the central authority is lost and for a period of time lawlessness may occur until it can be restored. Publicly-funded projects such as art or monumental architecture cease to proceed. A ‘dark age’ often follows as literacy declines precipitously and/or is lost altogether.

No new construction occurs and existing architecture tends to get reused by adapting it to current needs, such as subdividing great rooms. There may be attempts by some to carry on certain aspects of society, such as important ceremonies, but previously significant monuments are left to decay and may be repurposed for building materials. As buildings fall into disrepair and begin to collapse, residents will move to another or construct rather flimsy replacements.

Redistribution of goods and food tends to cease, with energy-averaging systems (i.e., trade) being reduced significantly. Craft specialisation declines and may be lost. Local self-sufficiency increases dramatically as regional interactions fall or cease altogether. Technologies simplify to a level that the local populace can create/maintain.

Settlements tend to be abandoned resulting in a rapid fall in population numbers and density, particularly in urban centres. In fact, the population decline may reach levels that had not been experienced in centuries or millennia.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

This breakdown of societal complexity has occurred repeatedly through time and across the planet. The above outlines what the pre/historical evidence suggests is the most likely trajectory of our global and industrial-based complex society as we stumble into an unknowable future.

There is little reason to believe our modern, technologically-based complex society is very much different from those that have preceded us — except perhaps to reduce the stress associated with cognitive dissonance.

The rise and then fall of a large, complex society seems certain. And, of course, the impacts are compounded tremendously by ecological overshoot.

In summary, as Tainter argues:

“In a complex society that has collapsed, it would thus appear, the overarching structure that provides support services to the population loses capability or disappears entirely. No longer can the populace rely upon external defense and internal order, maintenance of public works, or delivery of food and material goods. Organization reduces to the lowest level that is economically sustainable, so that a variety of contending polities exist where there had been peace and unity. Remaining populations must become locally self-sufficient to a degree not seen for several generations. Groups that had formerly been economic and political partners now become strange, even threatening competitors. The world as seen from any locality perceptibly shrinks, and over the horizon lies the unknown.” (p. 20)

Depending upon one’s perspective and thus interpretive lens, these various changes could be viewed as shifts for the better and not cataclysmic as many suggest. For example, less stratification and social regimentation may appeal to many who perceive our governing elite as far more on the authoritarian/totalitarian end of the political spectrum than they would like, and/or hope for a more equitable world in which social class plays a reduced or nonexistent role.

On the other hand, less economic and occupational specialisation, sharing, trading, redistribution of resources, and overall coordination and organisation necessarily implies that not only will populations depend far more on the skills and knowledge of their more localised communities/regions but also upon the local resources and organisational abilities.

This local self-reliance aspect I can see as a problem for many communities. And it may be especially so for modern society and its dependence upon technologies that will break down and/or become unusable due to their fuel/power requirements. Add to this the fact that the vast majority of regions depend significantly upon trade (or energy-averaging systems) to ensure such necessities as potable water, food, and regional shelter needs, and few if any people hold the skills/knowledge for self-sufficiency and it seems certain mass chaos will ensue.

Compounding this tragic mix for society are the dangerous complexities we’ve constructed and that require constant management and security to prevent them from breaking down and possibly resulting in massive environmental/ecological destruction: nuclear power plants with their radiogenic materials; biosafety labs and their deadly pathogens; chemical production and storage facilities and their toxic products and waste.

There are no guarantees when it comes to predictions about the future of humanity. This is particularly true when it comes to complex systems with their nonlinear feedback loops and emergent phenomena. There is almost an endless range of possibilities of what the future holds…but as Meadows et al. argue in the quote that opened this post: “… the possible futures do not include indefinite growth in physical throughputs. This is not an option on a finite planet.”

And, I offer no ‘solution’ to any of the above. I have increasingly come to hold that this is all one humungous predicament without a ‘solution’. The best we might hope for is to increase local self-sufficiency of communities and cross our fingers that some might make it through the impending transition that will be the result of complex society collapse compounded by ecological overshoot. On the other hand, all the other species on our planet might be hoping for our extinction given our track record of destructive tendencies…

If you’ve made it to the end of this contemplation and have got something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website or the link below — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers).

Attempting a new payment system as I am contemplating shutting down my site in the future (given the ever-increasing costs to keep it running).

If you are interested in purchasing any of the 3 books individually or the trilogy, please try the link below indicating which book(s) you are purchasing.

Costs (Canadian dollars):

Book 1: $2.99

Book 2: $3.89

Book 3: $3.89

Trilogy: $9.99

Feel free to throw in a ‘tip’ on top of the base cost if you wish; perhaps by paying in U.S. dollars instead of Canadian. Every few cents/dollars helps…

https://paypal.me/olduvaitrilogy?country.x=CA&locale.x=en_US

If you do not hear from me within 48 hours or you are having trouble with the system, please email me: olduvaitrilogy@gmail.com.

You can also find a variety of resources, particularly my summary notes for a handful of texts, especially Catton’s Overshoot and Tainter’s Collapse: see here.

It Bears Repeating: Best Of…Volume 1

A compilation of writers focused on the nexus of limits to growth, energy, and ecological overshoot.

With a Foreword and Afterword by Michael Dowd, authors include: Max Wilbert; Tim Watkins; Mike Stasse; Dr. Bill Rees; Dr. Tim Morgan; Rob Mielcarski; Dr. Simon Michaux; Erik Michaels; Just Collapse’s Tristan Sykes & Dr. Kate Booth; Kevin Hester; Alice Friedemann; David Casey; and, Steve Bull.

The document is not a guided narrative towards a singular or overarching message; except, perhaps, that we are in a predicament of our own making with a far more chaotic future ahead of us than most imagine–and most certainly than what mainstream media/politics would have us believe.

Click here to access the document as a PDF file, free to download.If you’ve made it to the end of this contemplation and have got something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers). Encouraging others to read my work is also much appreciated.

[1] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[2] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[3] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[4] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[6] See this, this, this, this, this, this, this, this, and/or this.

[7] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[8] See this, this, this, this, and/or this.

August 27, 2025

The Bulletin: August 20-26, 2025

If you’re new to my writing, check out this overview .

The Machine that Is Eating the Earth – by David Haggith

Global Nuclear Power Hits Record High as Asia Surges Ahead | OilPrice.com

Why Oil Prices Don’t Rise To Consistently High Levels

The High Priest of Ecomodernism and His Dangerous Faith | Art Berman

What If Preventing Collapse Isn’t Profitable? – resilience

Why do leaders & the public deny peak oil & limits to growth?

The Age Of Great Meteorological Uncertainty, We Need A New Type Of Climate Science

Scrutinizing ‘Hope’ and Popular Strategies and Goals

Facing Extinction — COLLAPSE PSYCHOLOGY

What Is Regenerative Farming, From A Scientific Standpoint, and Why Should We Care?

Gas ‘crisis’ warning – The World According to Fast Eddy

BlackRock’s bid for Minnesota Power worries consumer advocates

America’s fragile drug supply chain is extremely vulnerable to climate change – Ars Technica

Ozone will warm planet more than first thought, study finds

Beyond CO₂: How Ozone Is Heating the Planet Faster Than We Realize

Jack Alpert on the Human Predicament | Damn the Matrix

One Third Of All Energy Used Is Now Clean Energy

Brazil authorities suspend key Amazon rainforest protection measure | Environment | The Guardian

Key Blindspots of the “Walrus” Movement – by Nate Hagens

Banks Collapse. Governments Lie. Trust Survives.

How to Make Money Off of the Apocalypse

Collapse: A Framework for Understanding and Navigating the Decline of Industrial Civilisation

The Sustainability Crisis: We Don’t Know How to Live Within Limits

New study confirms “abrupt changes” underway in Antarctica

Moisture in the atmosphere causes extreme weather to last longer – Earth.com

#308: The coming deconstruction of global money | Surplus Energy Economics

Discontent Grows as Bulgaria Hit by New Water Supply Crisis | Balkan Insight

The Earth is under chemical attack – by Julian Cribb

Money for Nothing – by Nathan Knopp – System Failure

The End of Post-Industrial Nations – The Honest Sorcerer

This is the coolest summer for the rest of your life

Conspiracy Theories Revisited – OffGuardian

New YouTube video explaining government money creation to Ray Dalio

The Collapse of Climate Science. The Role of the COVID-19 Story

Science Snippets: Why We Must Protect the Global Ocean Forever

The Silence of the Birds – by Geoffrey Deihl

Vulture Extinction: A Red Alert for Planetary Collapse

Our Mafioso Economy – Charles Hugh Smith’s Substack

Get Ready For Trump’s Monetary Reset – Doug Casey’s International Man

ANOTHER DEEPER DIVE: The Detonator for another 2008 Housing Crisis Has Arrived!

Over 600 000 evacuated, one dead as Typhoon Kajiki makes landfall in Vietnam – The Watchers

Nature can keep up with climate change – but not at this speed

How To Prepare For The Collapse Of Society Like Billionaires Are

No Soil and Water Before 100% Renewable Energy

Unpacking the coloniality of energy, seeking alternatives from below – resilience

On Human Thinking and Longevity

If you have arrived here and get something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website or the link below — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers).

Attempting a new payment system as I am contemplating shutting down my site in the future (given the ever-increasing costs to keep it running).

If you are interested in purchasing any of the 3 books individually or the trilogy, please try the link below indicating which book(s) you are purchasing.

Costs (Canadian dollars):

Book 1: $2.99

Book 2: $3.89

Book 3: $3.89

Trilogy: $9.99

Feel free to throw in a ‘tip’ on top of the base cost if you wish; perhaps by paying in U.S. dollars instead of Canadian. Every few cents/dollars helps…

https://paypal.me/olduvaitrilogy?country.x=CA&locale.x=en_US

If you do not hear from me within 48 hours or you are having trouble with the system, please email me: olduvaitrilogy@gmail.com.

You can also find a variety of resources, particularly my summary notes for a handful of texts, especially William Catton’s Overshoot and Joseph Tainter’s Collapse of Complex Societies: see here.

August 20, 2025

The Bulletin: August 13-19, 2025

If you’re new to my writing, check out this overview .

Science Snippets: Connecting War with Climate Change

The Forgotten Skills of Dying and Grieving Well: How Engaging with Loss Can Help Us Live More Fully

You Can’t Make This Shit Up – by Michael Campi

The Untold Story of How Plants & Trees Cool Their Surroundings

Degrowth Needs Teambuilding – by Matt Orsagh

Inflation Comes in for a Summer Scorcher – by David Haggith

Ducks and Blueberries: A Reflection on Price, Cost and Value

The Myth of the Social Contract – by Justin McAffee

Clear-Cutting Triggers 18x More Floods, for 40+ Years

The Aftermath Of a Regional Nuclear War

With waters at 32C, Mediterranean tropicalization shifts into high gear

10 Rest Stops on the Way to Olduvai Cliff

Sanctions Are Just as Deadly as War: Lancet Study | The Libertarian Institute

The Trillion-Dollar Military-Industrial Complex

The Sloth Economy – The Honest Sorcerer

Doomerism at the End of the Universe – Watching the World Go Bye

Science Snippets: New, Huge Source of Carbon Dioxide Emissions

Q: What Happens When Insurance Fails? – by Matt Orsagh

Some Suggestions – by Caitlin Johnstone

The End of Modernity? Or the ‘Back Loop’ of Civilisation

Myths You Should Choose To Believe – by Justin McAffee

How Much Energy Does ChatGPT’s Newest Model Consume? | OilPrice.com

Earth’s Continents Are Drying Out at an Unprecedented Rate, Study Warns : ScienceAlert

Debunking Green Growth: What They Won’t Tell You | by Adam Lantz | The New Climate. | Medium

Why do leaders & the public deny peak oil & limits to growth?

U.S. East Coast On Alert As Powerful Hurricane Erin Approaches | ZeroHedge

If you have arrived here and get something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website or the link below — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers).

Attempting a new payment system as I am contemplating shutting down my site in the future (given the ever-increasing costs to keep it running).

If you are interested in purchasing any of the 3 books individually or the trilogy, please try the link below indicating which book(s) you are purchasing.

Costs (Canadian dollars):

Book 1: $2.99

Book 2: $3.89

Book 3: $3.89

Trilogy: $9.99

Feel free to throw in a ‘tip’ on top of the base cost if you wish; perhaps by paying in U.S. dollars instead of Canadian. Every few cents/dollars helps…

https://paypal.me/olduvaitrilogy?country.x=CA&locale.x=en_US

If you do not hear from me within 48 hours or you are having trouble with the system, please email me: olduvaitrilogy@gmail.com.

You can also find a variety of resources, particularly my summary notes for a handful of texts, especially William Catton’s Overshoot and Joseph Tainter’s Collapse of Complex Societies: see here.

August 15, 2025

Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CCXI–Collapse, Environment, and Society

Collapse, Environment, and Society is a 2012 article by geographer Karl Butzer (see: here and here) whose academic career focussed upon the relationship between humans and their environment.

In this article (summarised in more detail below), Butzer takes issue with often oversimplified narratives regarding societal ‘collapse’. He argues that societal decline is rarely sudden or the result of individual factors such as environmental degradation that many suggest. He finds the meaning of ‘collapse’ is often used in an ambiguous fashion and that the process involves complex interactions between the environment, demographic factors, and sociopolitical systems.

After providing some historical perspectives (i.e., Ibn Khaldun, Gibbon, social Darwinism, Spengler, and the Annales School) and reviewing some case studies (i.e., Old Kingdom Egypt, New Kingdom Egypt, Islamic Mesopotamia), he proposes an integrated model of collapse.

This model considers:

Preconditioning: long-term stressors that weaken a society’s resilience and ability to respond to challenges well (e.g., socioeconomic decline, environmental degradation, institutional incompetence/corruption).Triggers: short-term events that can push social systems over a threshold and result in significant crises (e.g., severe weather/climate events, major scandal, invasion).Cascading feedback: systemic crises can get amplified via interacting failures and feedback loops, leading to a situation whereby the society in question cannot respond to adequately (e.g., economic decline ←→ elite conflict ←→ civil war ←→ famine ←→ depopulation).Resilience factors: the consequences of the above for any society depend greatly upon the degree of political cohesion amongst the elite, environmental elasticity, and cultural persistence.Butzer argues that in this ‘collapse equation’ social factors (e.g., civil strife, invasion, institutional failure) are more impactful than environmental ones, although climate perturbations can act as a trigger. He suggests complexity is central, with collapse being the result of unpredictable interactions between societal systems and environmental variables.

He asserts that societal resilience in the face of building crises is quite possible and a variety of societies have avoided ‘collapse’ by way of adaptation and reorganisation. He further contends that the evidence suggests decentralised and flexible systems tend to be more resilient and may avoid collapse in the face of cascading stressors, but centralised and authoritarian ones tend not to as they are inflexible and struggle to adapt to changes.

In conclusion, Butzer advocates for deeper, cross-disciplinary research to determine the best approaches to avoiding/mitigating collapse.

A handful of my Contemplations that focus on societal ‘collapse’:

‘Collapse’: It May Not Be What You Think It Is (WebsiteMediumSubstack)

A ‘Great Simplification’ Is On Our Doorstep (Website Medium Substack)

Imperial Longevity, ‘Collapse’ Causes, and Resource Finiteness (Website Medium Substack)

Beyond Peak Oil: Will Our Cities Collapse? (Website Medium Substack)

Societal Collapse, Abrupt Climate Events, and the Role of Resilience (Website Medium Substack)

Beyond Collapse: Climate Change and Causality During the Middle Holocene Climatic Transition (Website Medium Substack)

Collapse = Prolonged Period of Diminishing Returns + Significant Stress Surge(s): Part 1 (Website Medium Substack) Part 2 (WebsiteMedium Substack) Part 3 (Website Medium Substack) Part 4 (Website Medium Substack)

The notion of societal ‘collapse’ carries with it a variety of interpretations. The word itself implies a ‘sudden’ change in society-as-a-whole–one day you just wake up and things have gone completely sideways. This is not what the archaeological evidence suggests tends to happen. ‘Collapse’ is typically a relatively long and drawn-out affair that takes place over generations; a gradual decline/simplification that may experience periodic ‘recovery’ or ‘moments’ of more ‘stressful’ events that cannot be responded to well. It is, as the following graphic demonstrates, a roller-coaster type journey with various peaks and valleys–the deep valleys may be considered ‘collapse’ relative to the high peaks.

What we call the approaching phase shift/collapse/simplification/unravelling is perhaps moot. It’s perhaps what we do/say/think in the face of it that matters most–and I don’t mean that in a ‘let’s-solve-this-problem’ kind of way for our problem solving tends to be via technological quick-fixes that exacerbate our predicaments.

Can we avoid authoritarian responses by the elite? Can we reduce the ‘suffering’ that may characterise certain times? Can we avoid violent responses by some? Can we maintain our ‘humanity’ in the face of decline? Can we adapt/recover?

The past shows us what tends to happen as our societies ‘devolve’ from their peaks of complexity and ‘progress’. Individuals/families/communities/nations can use this information to help inform them about probable futures and prepare for that as much as they can. That is perhaps the best that a region/community may accomplish in the face of an unknowable future.

A handful of my Contemplations that look into ‘collapse’ consequences for a society:

Societal ‘Collapse’: Past is Prologue (Website Medium Substack)

What Do Previous Experiments In Societal Complexity Suggest About ‘Managing’ Our Future (Website Medium Substack)

Ruling Caste Responses to Societal Breakdown/Decline (Website Medium Substack)

Energy Future, Part 1 (Website Medium Substack) Part 2: Competing Polities and Geopolitical Stress (Website Medium Substack) Part 3: Authoritarianism and Sociobehavioural Control (Website Medium Substack) Part 4: Economic Manipulation (Website Medium Substack)

This future-prepping based upon past experiences is unlikely on a broad scale, however, given all the pressures to believe such things as the ‘free’ market, sociopolitical systems, and/or human ingenuity and technology will somehow save/maintain our current arrangements or, better yet, propel humanity into a prosperous and equitable techno-utopia. It is more likely that the decision-and policy-makers will double- and triple-down on the strategies that have put us in this bind and trapped us all: increasing complexity by way of technical-based problem solving–especially, most recently, mass-produced industrial technologies that the ruling elite profit from (see: Keep Calm and Carry On…Human Ingenuity and Technology Will Save Us! Part 1 (Website Medium Substack) Part 2 (Website Medium Substack) Part 3 (Website Medium Substack)).

Butzer’s call to search for practices that help make a community more resilient is useful and much has been uncovered over the past number of decades in this regard [see here], but at some point the theorising and research must give way to actionable practices to be put in place by individuals and communities. Action over words, as it were, as it seems it is well past time for humanity to recognise that we are all caught in a trap of our own making and there’s no escape.

It seems prudent to search for like-minded people in your local community and pursue some things that might help your neighbours and the planet in general build resilience, and in a fashion that doesn’t contribute to our predicaments as most of humanity’s ‘solutions’ do. My suggestion is to pursue local strategies of resilience-building (e.g., decentralised and flexible practices that provide the basic necessities of living and support for communities). Putting in place practices that might help your locality be just a bit more resilient as our complex societies continue their inevitable ‘reversion to the mean’ of living arrangements on a finite planet with an unpredictable environment might be the best one can do as far as ‘preparing’ for ‘collapse’.

What follows are my thoughts as I read through Butzer’s article. As such, there may be rather abrupt shifts in the discourse that follows.

Societal simplification/devolution/collapse appears multicausal and rarely abrupt. Structures of authority breakdown, demographic decline occurs, environmental and economic crises arise, famine ensues, etc.. In criticising ‘alarmist literature’ for being unhelpful and simplistic, Butzer tends to swing in the opposite direction by emphasising those instances where resilience and adaptation due to ‘enlightened leadership’ and ‘cultural solidarity’ were successful in avoiding ‘collapse’.

The reference to Social Darwinism and the notion that technology can solve any problem/issue. demonstrates that sociocultural influences affect scientific paradigms and the interpretation of observable evidence. For any that have not read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions, it is well worth the time to review this fundamental treatise on the impact of one’s worldview/paradigm on scientific research.

Butzer’s critique of the research focus on climate/environment as THE causal agent of collapse is quite warranted given such an approach is an example of the very common phenomenon of reductionism whereby singular or a narrow cause of our predicaments is identified as the sole or primary ‘problem’. Unfortunately what accompanies this tendency to oversimplify is the associated notion that if only this or that singular variable could be addressed, all will be well again: reduce/stop carbon emissions; eliminate/transform capitalism; elect the ‘right’ leader; tax the wealthy…None of these reductionist arguments are relevant given the complexity of the predicaments and the lack of agency individuals/groups have in affecting the perceived ‘problem’.

The discussion on the emergence of a military-priestly caste (superstitious-driven theocracy) as society collapses reminds me of the growing complexity and associated increase in fragility that occurs as we attempt to ‘solve’ issues/problems, and, thus, of Tainter’s thesis regarding human societies being problem-solving organisations. In attempting to address ‘problems’ in ways that increase complexity (and produce more ‘problems’) we eventually get results that create over-burdening ‘costs’ for the majority. This, in turn, leads to the subsequent ‘opting-out’ of participants, thus reducing support and ‘investments’ in the system as a whole and contributing to ‘collapse’. In fact, Butzer’s proposed model very much mirrors Tainter’s.

Significant tax increases, one of the contributing factors cited by Butzer with respect to Mesopotamia’s decline, are present in today’s nations but are perhaps less obvious due to: increasing national debt levels (i.e., relative to ways in the past, spending can far exceed revenues, and growth is ‘stolen’ from the future to prop up the present displacing the burden temporarily); the way in which fiat currency can be devalued; and, the narrative management over price inflation causes–especially the idea that ‘low’ inflation is beneficial.

The preconditioning factor for environmental subsystems Butzer refers to appears to be classic diminishing returns on resource extraction whereby the easiest-to-extract resources are used first with relatively lower environmental impacts. As the more-difficult-to-extract resources are sought, environmental impacts increase. In fact, much of Butzer’s thesis and his ‘collapse’ model seem very reflective of Joseph Tainter’s work as I discuss above. Butzer and Tainter were contemporary researchers focussed on the same topic, but Butzer never cites Tainter or mentions his work–quite surprising given the extent to which Tainter’s research has influenced the field of societal collapse. Tainter, on the other hand, did cite and mention Butzer’s work.

Butzer’s perspective on deforestation (that it can be viewed as positive) is rather narrow in that it only raises the issue of plant diversity and misses all of the other ecosystem disruptions/destruction that occurs, especially regarding the animal species present in forests. He further argues for the future possibility of using the deforested land for human purposes without consideration of the non-human species that have lost habitat. We are also learning about the impacts on other systems (e.g., climate/weather, hydrological cycle, etc.) as a result of deforestation/land system use change.

When incompetent rulers fall, and collapse ensues, new elites can ally with others. It appears that societies experience ‘waves’ of complexity and simplification with ‘collapse’ being a somewhat arbitrary ‘classification’–think of punctuated equilibria with longish periods of stability (slowly increasing complexity) with periodic and relatively short periods of rapid change (simplification)–see graphic above.

On collapse narratives being impacted by societal views: this is an important aspect to keep at the top of one’s mind in considering ‘collapse’ narratives (or any narratives for that matter)–stories often reflect societal norms, biases, etc. and the variables stressed in any theory may not have been as relevant to a pre/historical society. The written records that do exist and refer to problematic societal issues tend to be rather narrow and focussed upon the ‘elite’ class. As pre/history suggests, ‘collapse’ may actually be a relatively positive outcome for the masses (see this); although this may not be the case for modernity’s decline given the loss of self-reliance skills and knowledge by the majority of the world’s population.

The suggestion of socioeconomic integration (i.e., the promotion of wealth equity) is an interesting one that requires some unpacking since it is often, if not always, used in a way that argues for raising the far more disadvantaged up to the level of the far more advantaged. This approach, however, flies in the face of our ecological overshoot predicament since it basically is a call-to-arms for increased consumption–and thus increased extraction and refining of resources that contribute to the continued overloading of compensatory sinks. Raising the masses up to the level of the top 10-20% of wealth earners would likely put the icing on the cake towards the complete destruction of our ecological systems from which there would be no ‘resilient response’ for future generations of our species. It would also tend to increase societal complexity in the face of diminishing returns, leading to even more fragile human systems. It seems to me that we want to be looking at ways to simplify our societies and significantly decrease the ecologically-destructive practices that increased consumption brings, which is dominated by the more ‘advantaged’ members of our species.

Collapse, Environment, and Society

Karl W. Butzer

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, March 6, 2012, Vol. 109, No. 10, pp. 3632-3639

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41507011

Abstract

“Historical collapse of ancient states poses intriguing social-ecological questions, as well as potential applications to global change and contemporary strategies for sustainability. Five Old World case studies are developed to identify interactive inputs, triggers, and feedbacks in devolution. Collapse is multicausal and rarely abrupt. Political simplification undermines traditional structures of authority to favor militarization, whereas disintegration is preconditioned or triggered by acute stress (insecurity, environmental or economic crises, famine), with breakdown accompanied or followed by demographic decline. Undue attention to stressors risk underestimating the intricate interplay of environmental, political, and sociocultural resilience in limiting the damages of collapse or in facilitating reconstruction. The conceptual model emphasizes resilience, as well as the historical roles of leaders, elites, and ideology. However, a historical model cannot simply be applied to contemporary problems of sustainability without adjustment for cumulative information and increasing possibilities for popular participation. Between the 14th and 18th centuries, Western Europe responded to environmental crises by innovation and intensification; such modernization was decentralized, protracted, flexible, and broadly based. Much of the current alarmist literature that claims to draw from historical experience is poorly focused, simplistic, and unhelpful. It fails to appreciate that resilience and readaptation depend on identified options, improved understanding, cultural solidarity, enlightened leadership, and opportunities for and fresh ideas.”

Butzer contends that the growth-contraction change of societies over time appears to be cyclical with failure in one systemic network impacting associated ones. However, using the term ‘collapse’ to describe such shifts can be problematic since it has rather ambiguous meaning with unanswered questions regarding timeframes, elements of failure, and whether the ‘collapse’ allows for adaptive restructuring.

Interest in this recurrent phenomenon can be traced back to historian Ibn Khaldun (1377 Common Era/CE) and rippled through the West with Edward Gibbon’s treatise on the Roman Empire. 19th Century archaeology ‘uncovered’ many examples, with theories for societal ‘failure’ being shaped by the dominant ideas of the time (e.g., biological evolution). Social Darwinists, for example, believed material culture demonstrated ‘progress’, with the West showing technology could ensure lasting economic growth by solving any issue encountered. Spengler’s The Decline of the West was perhaps the first to provide some insights towards sociopolitical resilience to avoid ‘collapse’.

Butzer argues that what’s ”[n]otable is the increasing diversity of perspectives about collapse, ranging initially from ethical and social, to ideological or ethnocentric, and eventually to interdisciplinary and systemic… the challenge for a scientific study of historical collapse remains to develop comprehensive, integrated or coupled models, drawing upon the implications of qualitative narratives that go well beyond routine social science categories, to better incorporate the complexity of human societies.” (p. 3633)

He further raises concern that current research was avoiding this cross-disciplinary integration and the complexity of the interrelationships between multiple variables through its focus upon climate and environmental degradation as the ultimate causal agents in societal change. HIs hope is to help create a complex simulation model with societal aspects that can help identify the variables that are vital to system resilience.

Butzer’s first case study is that of Old Kingdom Egypt. He argues that a “concatenation of triggering economic, subsistence, political, and social forces probably drove Egypt across a threshold of instability, setting in train a downward spiral of cascading feedbacks.” (p. 3634). Eventually, however, new elites restored the ‘cosmic order’ via military force. The initial decline was over several decades with the collapse process lasting a century or more (as did restoration) and demonstrates that it is a very complex process involving systemic interaction and encompassing people at cross purposes using incomplete information in their attempts to restore order.

Second, Butzer examines New Kingdom Egypt. Failures of the Nile River led eventually to a food crisis (1170-1110 BCE) and that was “preconditioned by (i) debilitating wars to repel invaders, (ii) the loss of Mediterranean commerce, (iii) official corruption, and (iv) a lack of support from the priesthood controlling the temple granaries” (p. 3635). State division and growing fragmentation contributed to continuing economic decline even after the food crisis passed with the literature of the time highlighting violence, arbitrary rule, hunger, excessive taxes, and increasing social discord. It seems that the response to growing issues was not resilience but a military-priestly caste; a superstitious-driven theocracy.

Finally, Butzer analyses Islamic Mesopotamia where two collapses occurred during a 700 year stretch. These collapses occurred in the wake of the Arab Conquest (640 CE) and during the 10th century, concluding with the Mongol plundering of Baghdad (1258 CE). The first collapse took a century, while the second about three centuries and were similar in their fallout: fiscal mismanagement, land use change, war, and irrigation difficulties.