Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CCXI–Collapse, Environment, and Society

Collapse, Environment, and Society is a 2012 article by geographer Karl Butzer (see: here and here) whose academic career focussed upon the relationship between humans and their environment.

In this article (summarised in more detail below), Butzer takes issue with often oversimplified narratives regarding societal ‘collapse’. He argues that societal decline is rarely sudden or the result of individual factors such as environmental degradation that many suggest. He finds the meaning of ‘collapse’ is often used in an ambiguous fashion and that the process involves complex interactions between the environment, demographic factors, and sociopolitical systems.

After providing some historical perspectives (i.e., Ibn Khaldun, Gibbon, social Darwinism, Spengler, and the Annales School) and reviewing some case studies (i.e., Old Kingdom Egypt, New Kingdom Egypt, Islamic Mesopotamia), he proposes an integrated model of collapse.

This model considers:

Preconditioning: long-term stressors that weaken a society’s resilience and ability to respond to challenges well (e.g., socioeconomic decline, environmental degradation, institutional incompetence/corruption).Triggers: short-term events that can push social systems over a threshold and result in significant crises (e.g., severe weather/climate events, major scandal, invasion).Cascading feedback: systemic crises can get amplified via interacting failures and feedback loops, leading to a situation whereby the society in question cannot respond to adequately (e.g., economic decline ←→ elite conflict ←→ civil war ←→ famine ←→ depopulation).Resilience factors: the consequences of the above for any society depend greatly upon the degree of political cohesion amongst the elite, environmental elasticity, and cultural persistence.Butzer argues that in this ‘collapse equation’ social factors (e.g., civil strife, invasion, institutional failure) are more impactful than environmental ones, although climate perturbations can act as a trigger. He suggests complexity is central, with collapse being the result of unpredictable interactions between societal systems and environmental variables.

He asserts that societal resilience in the face of building crises is quite possible and a variety of societies have avoided ‘collapse’ by way of adaptation and reorganisation. He further contends that the evidence suggests decentralised and flexible systems tend to be more resilient and may avoid collapse in the face of cascading stressors, but centralised and authoritarian ones tend not to as they are inflexible and struggle to adapt to changes.

In conclusion, Butzer advocates for deeper, cross-disciplinary research to determine the best approaches to avoiding/mitigating collapse.

A handful of my Contemplations that focus on societal ‘collapse’:

‘Collapse’: It May Not Be What You Think It Is (WebsiteMediumSubstack)

A ‘Great Simplification’ Is On Our Doorstep (Website Medium Substack)

Imperial Longevity, ‘Collapse’ Causes, and Resource Finiteness (Website Medium Substack)

Beyond Peak Oil: Will Our Cities Collapse? (Website Medium Substack)

Societal Collapse, Abrupt Climate Events, and the Role of Resilience (Website Medium Substack)

Beyond Collapse: Climate Change and Causality During the Middle Holocene Climatic Transition (Website Medium Substack)

Collapse = Prolonged Period of Diminishing Returns + Significant Stress Surge(s): Part 1 (Website Medium Substack) Part 2 (WebsiteMedium Substack) Part 3 (Website Medium Substack) Part 4 (Website Medium Substack)

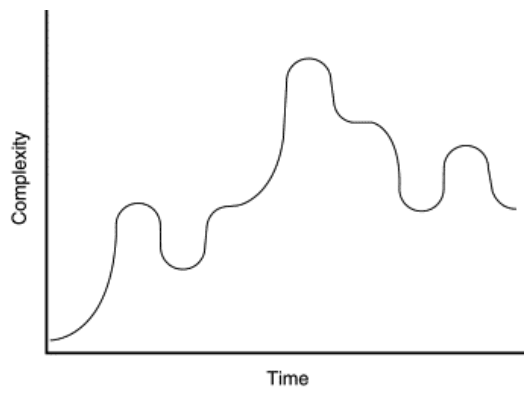

The notion of societal ‘collapse’ carries with it a variety of interpretations. The word itself implies a ‘sudden’ change in society-as-a-whole–one day you just wake up and things have gone completely sideways. This is not what the archaeological evidence suggests tends to happen. ‘Collapse’ is typically a relatively long and drawn-out affair that takes place over generations; a gradual decline/simplification that may experience periodic ‘recovery’ or ‘moments’ of more ‘stressful’ events that cannot be responded to well. It is, as the following graphic demonstrates, a roller-coaster type journey with various peaks and valleys–the deep valleys may be considered ‘collapse’ relative to the high peaks.

What we call the approaching phase shift/collapse/simplification/unravelling is perhaps moot. It’s perhaps what we do/say/think in the face of it that matters most–and I don’t mean that in a ‘let’s-solve-this-problem’ kind of way for our problem solving tends to be via technological quick-fixes that exacerbate our predicaments.

Can we avoid authoritarian responses by the elite? Can we reduce the ‘suffering’ that may characterise certain times? Can we avoid violent responses by some? Can we maintain our ‘humanity’ in the face of decline? Can we adapt/recover?

The past shows us what tends to happen as our societies ‘devolve’ from their peaks of complexity and ‘progress’. Individuals/families/communities/nations can use this information to help inform them about probable futures and prepare for that as much as they can. That is perhaps the best that a region/community may accomplish in the face of an unknowable future.

A handful of my Contemplations that look into ‘collapse’ consequences for a society:

Societal ‘Collapse’: Past is Prologue (Website Medium Substack)

What Do Previous Experiments In Societal Complexity Suggest About ‘Managing’ Our Future (Website Medium Substack)

Ruling Caste Responses to Societal Breakdown/Decline (Website Medium Substack)

Energy Future, Part 1 (Website Medium Substack) Part 2: Competing Polities and Geopolitical Stress (Website Medium Substack) Part 3: Authoritarianism and Sociobehavioural Control (Website Medium Substack) Part 4: Economic Manipulation (Website Medium Substack)

This future-prepping based upon past experiences is unlikely on a broad scale, however, given all the pressures to believe such things as the ‘free’ market, sociopolitical systems, and/or human ingenuity and technology will somehow save/maintain our current arrangements or, better yet, propel humanity into a prosperous and equitable techno-utopia. It is more likely that the decision-and policy-makers will double- and triple-down on the strategies that have put us in this bind and trapped us all: increasing complexity by way of technical-based problem solving–especially, most recently, mass-produced industrial technologies that the ruling elite profit from (see: Keep Calm and Carry On…Human Ingenuity and Technology Will Save Us! Part 1 (Website Medium Substack) Part 2 (Website Medium Substack) Part 3 (Website Medium Substack)).

Butzer’s call to search for practices that help make a community more resilient is useful and much has been uncovered over the past number of decades in this regard [see here], but at some point the theorising and research must give way to actionable practices to be put in place by individuals and communities. Action over words, as it were, as it seems it is well past time for humanity to recognise that we are all caught in a trap of our own making and there’s no escape.

It seems prudent to search for like-minded people in your local community and pursue some things that might help your neighbours and the planet in general build resilience, and in a fashion that doesn’t contribute to our predicaments as most of humanity’s ‘solutions’ do. My suggestion is to pursue local strategies of resilience-building (e.g., decentralised and flexible practices that provide the basic necessities of living and support for communities). Putting in place practices that might help your locality be just a bit more resilient as our complex societies continue their inevitable ‘reversion to the mean’ of living arrangements on a finite planet with an unpredictable environment might be the best one can do as far as ‘preparing’ for ‘collapse’.

What follows are my thoughts as I read through Butzer’s article. As such, there may be rather abrupt shifts in the discourse that follows.

Societal simplification/devolution/collapse appears multicausal and rarely abrupt. Structures of authority breakdown, demographic decline occurs, environmental and economic crises arise, famine ensues, etc.. In criticising ‘alarmist literature’ for being unhelpful and simplistic, Butzer tends to swing in the opposite direction by emphasising those instances where resilience and adaptation due to ‘enlightened leadership’ and ‘cultural solidarity’ were successful in avoiding ‘collapse’.

The reference to Social Darwinism and the notion that technology can solve any problem/issue. demonstrates that sociocultural influences affect scientific paradigms and the interpretation of observable evidence. For any that have not read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions, it is well worth the time to review this fundamental treatise on the impact of one’s worldview/paradigm on scientific research.

Butzer’s critique of the research focus on climate/environment as THE causal agent of collapse is quite warranted given such an approach is an example of the very common phenomenon of reductionism whereby singular or a narrow cause of our predicaments is identified as the sole or primary ‘problem’. Unfortunately what accompanies this tendency to oversimplify is the associated notion that if only this or that singular variable could be addressed, all will be well again: reduce/stop carbon emissions; eliminate/transform capitalism; elect the ‘right’ leader; tax the wealthy…None of these reductionist arguments are relevant given the complexity of the predicaments and the lack of agency individuals/groups have in affecting the perceived ‘problem’.

The discussion on the emergence of a military-priestly caste (superstitious-driven theocracy) as society collapses reminds me of the growing complexity and associated increase in fragility that occurs as we attempt to ‘solve’ issues/problems, and, thus, of Tainter’s thesis regarding human societies being problem-solving organisations. In attempting to address ‘problems’ in ways that increase complexity (and produce more ‘problems’) we eventually get results that create over-burdening ‘costs’ for the majority. This, in turn, leads to the subsequent ‘opting-out’ of participants, thus reducing support and ‘investments’ in the system as a whole and contributing to ‘collapse’. In fact, Butzer’s proposed model very much mirrors Tainter’s.

Significant tax increases, one of the contributing factors cited by Butzer with respect to Mesopotamia’s decline, are present in today’s nations but are perhaps less obvious due to: increasing national debt levels (i.e., relative to ways in the past, spending can far exceed revenues, and growth is ‘stolen’ from the future to prop up the present displacing the burden temporarily); the way in which fiat currency can be devalued; and, the narrative management over price inflation causes–especially the idea that ‘low’ inflation is beneficial.

The preconditioning factor for environmental subsystems Butzer refers to appears to be classic diminishing returns on resource extraction whereby the easiest-to-extract resources are used first with relatively lower environmental impacts. As the more-difficult-to-extract resources are sought, environmental impacts increase. In fact, much of Butzer’s thesis and his ‘collapse’ model seem very reflective of Joseph Tainter’s work as I discuss above. Butzer and Tainter were contemporary researchers focussed on the same topic, but Butzer never cites Tainter or mentions his work–quite surprising given the extent to which Tainter’s research has influenced the field of societal collapse. Tainter, on the other hand, did cite and mention Butzer’s work.

Butzer’s perspective on deforestation (that it can be viewed as positive) is rather narrow in that it only raises the issue of plant diversity and misses all of the other ecosystem disruptions/destruction that occurs, especially regarding the animal species present in forests. He further argues for the future possibility of using the deforested land for human purposes without consideration of the non-human species that have lost habitat. We are also learning about the impacts on other systems (e.g., climate/weather, hydrological cycle, etc.) as a result of deforestation/land system use change.

When incompetent rulers fall, and collapse ensues, new elites can ally with others. It appears that societies experience ‘waves’ of complexity and simplification with ‘collapse’ being a somewhat arbitrary ‘classification’–think of punctuated equilibria with longish periods of stability (slowly increasing complexity) with periodic and relatively short periods of rapid change (simplification)–see graphic above.

On collapse narratives being impacted by societal views: this is an important aspect to keep at the top of one’s mind in considering ‘collapse’ narratives (or any narratives for that matter)–stories often reflect societal norms, biases, etc. and the variables stressed in any theory may not have been as relevant to a pre/historical society. The written records that do exist and refer to problematic societal issues tend to be rather narrow and focussed upon the ‘elite’ class. As pre/history suggests, ‘collapse’ may actually be a relatively positive outcome for the masses (see this); although this may not be the case for modernity’s decline given the loss of self-reliance skills and knowledge by the majority of the world’s population.

The suggestion of socioeconomic integration (i.e., the promotion of wealth equity) is an interesting one that requires some unpacking since it is often, if not always, used in a way that argues for raising the far more disadvantaged up to the level of the far more advantaged. This approach, however, flies in the face of our ecological overshoot predicament since it basically is a call-to-arms for increased consumption–and thus increased extraction and refining of resources that contribute to the continued overloading of compensatory sinks. Raising the masses up to the level of the top 10-20% of wealth earners would likely put the icing on the cake towards the complete destruction of our ecological systems from which there would be no ‘resilient response’ for future generations of our species. It would also tend to increase societal complexity in the face of diminishing returns, leading to even more fragile human systems. It seems to me that we want to be looking at ways to simplify our societies and significantly decrease the ecologically-destructive practices that increased consumption brings, which is dominated by the more ‘advantaged’ members of our species.

Collapse, Environment, and Society

Karl W. Butzer

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, March 6, 2012, Vol. 109, No. 10, pp. 3632-3639

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41507011

Abstract

“Historical collapse of ancient states poses intriguing social-ecological questions, as well as potential applications to global change and contemporary strategies for sustainability. Five Old World case studies are developed to identify interactive inputs, triggers, and feedbacks in devolution. Collapse is multicausal and rarely abrupt. Political simplification undermines traditional structures of authority to favor militarization, whereas disintegration is preconditioned or triggered by acute stress (insecurity, environmental or economic crises, famine), with breakdown accompanied or followed by demographic decline. Undue attention to stressors risk underestimating the intricate interplay of environmental, political, and sociocultural resilience in limiting the damages of collapse or in facilitating reconstruction. The conceptual model emphasizes resilience, as well as the historical roles of leaders, elites, and ideology. However, a historical model cannot simply be applied to contemporary problems of sustainability without adjustment for cumulative information and increasing possibilities for popular participation. Between the 14th and 18th centuries, Western Europe responded to environmental crises by innovation and intensification; such modernization was decentralized, protracted, flexible, and broadly based. Much of the current alarmist literature that claims to draw from historical experience is poorly focused, simplistic, and unhelpful. It fails to appreciate that resilience and readaptation depend on identified options, improved understanding, cultural solidarity, enlightened leadership, and opportunities for and fresh ideas.”

Butzer contends that the growth-contraction change of societies over time appears to be cyclical with failure in one systemic network impacting associated ones. However, using the term ‘collapse’ to describe such shifts can be problematic since it has rather ambiguous meaning with unanswered questions regarding timeframes, elements of failure, and whether the ‘collapse’ allows for adaptive restructuring.

Interest in this recurrent phenomenon can be traced back to historian Ibn Khaldun (1377 Common Era/CE) and rippled through the West with Edward Gibbon’s treatise on the Roman Empire. 19th Century archaeology ‘uncovered’ many examples, with theories for societal ‘failure’ being shaped by the dominant ideas of the time (e.g., biological evolution). Social Darwinists, for example, believed material culture demonstrated ‘progress’, with the West showing technology could ensure lasting economic growth by solving any issue encountered. Spengler’s The Decline of the West was perhaps the first to provide some insights towards sociopolitical resilience to avoid ‘collapse’.

Butzer argues that what’s ”[n]otable is the increasing diversity of perspectives about collapse, ranging initially from ethical and social, to ideological or ethnocentric, and eventually to interdisciplinary and systemic… the challenge for a scientific study of historical collapse remains to develop comprehensive, integrated or coupled models, drawing upon the implications of qualitative narratives that go well beyond routine social science categories, to better incorporate the complexity of human societies.” (p. 3633)

He further raises concern that current research was avoiding this cross-disciplinary integration and the complexity of the interrelationships between multiple variables through its focus upon climate and environmental degradation as the ultimate causal agents in societal change. HIs hope is to help create a complex simulation model with societal aspects that can help identify the variables that are vital to system resilience.

Butzer’s first case study is that of Old Kingdom Egypt. He argues that a “concatenation of triggering economic, subsistence, political, and social forces probably drove Egypt across a threshold of instability, setting in train a downward spiral of cascading feedbacks.” (p. 3634). Eventually, however, new elites restored the ‘cosmic order’ via military force. The initial decline was over several decades with the collapse process lasting a century or more (as did restoration) and demonstrates that it is a very complex process involving systemic interaction and encompassing people at cross purposes using incomplete information in their attempts to restore order.

Second, Butzer examines New Kingdom Egypt. Failures of the Nile River led eventually to a food crisis (1170-1110 BCE) and that was “preconditioned by (i) debilitating wars to repel invaders, (ii) the loss of Mediterranean commerce, (iii) official corruption, and (iv) a lack of support from the priesthood controlling the temple granaries” (p. 3635). State division and growing fragmentation contributed to continuing economic decline even after the food crisis passed with the literature of the time highlighting violence, arbitrary rule, hunger, excessive taxes, and increasing social discord. It seems that the response to growing issues was not resilience but a military-priestly caste; a superstitious-driven theocracy.

Finally, Butzer analyses Islamic Mesopotamia where two collapses occurred during a 700 year stretch. These collapses occurred in the wake of the Arab Conquest (640 CE) and during the 10th century, concluding with the Mongol plundering of Baghdad (1258 CE). The first collapse took a century, while the second about three centuries and were similar in their fallout: fiscal mismanagement, land use change, war, and irrigation difficulties.

Egypt’s situation seems to have been more resilient and continued to function somewhat successfully despite the issues that arose. The failure of Mesopotamia’s irrigation system was ecologically tragic and resulted in an eventual wasteland.

Butzer suggests that little comparative research has been carried out on historical collapse, with the discourse tending towards a generalised, macroscopic perspective. The devolution of sociopolitical and socioeconomic markers have received little attention, as too has failed attempts to address such issues; in particular, sociocultural factors have rarely been considered. The heuristic model below in light of the case studies examined “suggest that the complexity of the social-ecological interface is as much about interrelationships as it is about the identification of stressors.” (p. 3635)

It would seem that a number of variables can serve to precondition a society for ‘collapse’; for example: a long and slow or short and intense economic decline; biotic resource degradation (e.g., soil, water, forests) in combination with destructive land use, incompetent governing, and rural flight; environmental subsystem failure due to poor resource productivity; climate/weather factors; population decline that feeds into food productivity and economic systems; war; conflict between domestic elite groups. The case studies appear to “indicate that environmental inputs mainly played supporting roles in a train of events set in motion by institutional incompetence or corruption, civil strife and insecurity, invasion, or pandemics.” (p. 3636)

With regard to the timeframe for ‘collapse’, it would appear that the initial stages may occur relatively quickly but the more complex collapse or reconstruction tends to take a century or more.

Human ecosystem resilience appears impacted by political, cultural, and environmental variables. European systems appear to have been less susceptible than arid near-Eastern societies, perhaps due to fragile, complex irrigation systems that required significant human inputs. When these required inputs became over-demanding, it appears the peasants abandoned their villages returning to a nomadic semi-pastoralist lifestyle. It seems that environmental resilience and not human-caused impairment is the main difference on a global scale but regionally anthropogenic damage (e.g., deforestation, land use change) can complicate matters. “Environmental elasticity may be critical in the mitigating of collapse, or in the ability of a society to carry on.” (p. 3637)

The ruling elite tend to support the State out of self interest and collapse can be reversed via a new dynasty composed of a new group of elite (typically with a different identity and political centre). History has shown that incompetent rulers may fall and collapse ensue, but periodically some of the surviving elite may ally with new ones to support a different ruler providing a means of resilience and stabilisation. Based on this, Butzer argues that a society’s elite can help with resilience and stabilisation, along with religious institutions. If they can rally some elite and societal institutions they may not stop collapse but can move events towards reconstruction via reimposition of law and order and societal cohesion.

The most fragile aspect during collapse appears to be sociopolitical structures with its hierarchical order being simplified and authority often transferred. Sociocultural traits, however, appear fairly resistant to change and can remain relatively intact for millennia despite other shifts (e.g., language, ethnic identity, religion).

Collapse typically involved demographic change via a variety of avenues (e.g., war, disease, famine, migration, expulsion); while a decline may not lead to collapse, it can result in stressing important societal systems (e.g., agriculture). Climatic perturbations or labour shortages (due to a pandemic) that impact food production can result in a breakdown of economic networks and simplification.

These case studies suggest:

Every breakdown appears to experience institutional failure early on due to incompetence, corruption, and/or economic decline.As critical as climate forcing are civil war or invasion to breakdown.Climate perturbation is far more often experienced than environmental degradation.Depopulation appears during and/or after collapse (commonly pathogen-driven).Overlapping with invasion and/or ethnic change is ideological change.“In other words, poor leadership, administrative dysfunction, and ideological ambivalence appear to be endemic to the processes of collapse. War or climatic perturbations possibly served as triggering mechanisms, but environmental degradation does not appear as a universal variable. Demographic decline was either a coagency or a delayed result of change, except for the Black Death. Collapse was a consequence of multiple factors, reinforced by various feedbacks and partially balanced by resilience, with unpredictable outcomes. The comparative importance of societal versus environmental inputs seems to favor the social side.” (p. 3638)

There exist a number of examples of societal collapse being avoided. Western Europe’s subsistence crises (post-1200 CE) with riots, wars, and revolts did not lead to sociopolitical change until the French Revolution. Recent history also sees economic and/or ecological disasters being ‘overcome’ and not resulting in collapse. Environmental crises (e.g., Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age) resulted in food production and distribution strategies as opposed to collapse.

It appears that the differences between recent history with earlier examples were structural in nature with Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt being authoritarian where change was more difficult and the flexibility needed to deal with crises was frowned upon. Knowing the past helps us to situate the present but provides no simple and prescriptive insights regarding societal risks for collapse.

Butzer concludes that ’alarmist’ literature that bases claims on the past tends to be simplistic and not helpful; instead, present societies should “turn their attention to information diffusion and socioeconomic integration, across class lines and different spatial scales.” (p. 3639)

Modern societies have a number of advantages over those of the past, particularly in the realm of available knowledge/information and engaged citizens. It is also necessary for societal elites to set aside ideological differences and come to agreement on the socioeconomic implications of global challenges, particularly as they have to do with climatic changes.

The more detailed summary notes (with my thoughts while reading as footnotes) can be found here.

If you have arrived here and get something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website or the link below — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers).

Attempting a new payment system as I am contemplating shutting down my site in the future (given the ever-increasing costs to keep it running).

If you are interested in purchasing any of the 3 books individually or the trilogy, please try the link below indicating which book(s) you are purchasing.

Costs (Canadian dollars):

Book 1: $2.99

Book 2: $3.89

Book 3: $3.89

Trilogy: $9.99

Feel free to throw in a ‘tip’ on top of the base cost if you wish; perhaps by paying in U.S. dollars instead of Canadian. Every few cents/dollars helps…

https://paypal.me/olduvaitrilogy?country.x=CA&locale.x=en_US

If you do not hear from me within 48 hours or you are having trouble with the system, please email me: olduvaitrilogy@gmail.com.

You can also find a variety of resources, particularly my summary notes for a handful of texts, especially William Catton’s Overshoot and Joseph Tainter’s Collapse of Complex Societies.