Chris McMahon's Blog, page 7

July 4, 2013

Drawing the Reader into Character

Is building sympathy for your character the key to hooking a reader?

Beginnings – and hooking the reader – have always been my bugbear. Big complex plots, interweaving stories, multiple characters, action scenes – no problem. Getting someone to read the story in the first place – Big Problem.

The difficulty is that what one reader responds to in a character is often vastly different to another – in fact often diametrically opposed. One reader’s cool detached hero is another’s arrogant, insufferable narcissist.

I used to come home from critique groups puzzled by contradictory comments that made little sense until the penny finally dropped. If people don’t like your characters, they will just not gel with your story. Once you reach that stage the critter will start (often unconsciously) working overtime to find all the things ‘wrong’ with your piece, when the real problem is that it simply has no resonance for them. They will talk vehemently about the punctuation on p3, or how they got mixed up in the dialogue, the logic error in par 5, or yada yada, yada… The same thing happens with editors. The reasons they give for rejecting your manuscript may have little to do with the real reason, which may be that they struggled to emotionally connect with the character.

Even very successful writers don’t seem to have real control over reader’s reactions.

One of David Gemmell readers all time favorite characters is Waylander. David Gemmell himself set out to make this guy a real piece of work – a nasty customer that no one should like; a ruthless assassin that kills without a thought. The surprise was that people loved Waylander, and he went on to be one of Gemmell’s most successful characters, extending over three books and carrying the story well in each one. So why did people respond to Waylander? Was there something unconsciously carried through from Gemmell about that character’s destiny that altered his portrayal? Or do people just love the bad guy – the old Sympathy for the Devil chestnut?

What really draws you into a character? Their sense of connection – the way they love someone else or show they care? Being the underdog? Strength? Courage? Determination? Their vulnerability? Their sheer undead coolness? Or is it something less tangible than that. Is it being able to relate to the ordinary troubles and mundane problems that you share with the character i.e. they may be an immortal space traveller, but they still get parking tickets at the spaceport?

Got any clues to share on building emotional resonance and sympathy for character?

June 27, 2013

Near-Future Fiction

Writing near-future SF or Fantasy can be a nerve-wracking experience. How do you portray your world in such a way that it seems futuristic and unique, but without falling into the bear-trap of predicting the wrong trends?

In some senses, it’s impossible to avoid. Particularly if the story itself is driven by a unique SF idea that requires a pretty specific type of setting. This makes it virtually impossible to avoid sketching a world that will not look like reality when it arrives.

If you are too true to real-world predictions, the setting will look boring. The pace of technological advancement rarely matches the rate at which a writer’s imagination can move (you only have to look at any Golden Age SF story to realise we should all be using rocket-packs and flying cars to get to work by now. OK, communication technology was the exception.). If you try to be too realistic, you are also in danger - paradoxically – of looking like you don’t understand technology or science. ‘What? He doesn’t even have wormholes?’ I find this a tricky balance. The engineer and futurist in me wants to sketch something that I believe is realistic in time-frame, but I am forced to go beyond this or risk my SF credibility in the eyes of editors and readers.

The best way to future-proof the fiction is to ensure that the story stands on its merits without the SF&F elements. The best SF stories of the Golden Age were driven as much by a true rendering of human emotions and drives as they were by their futuristic SF predictions. The key dilemma may have arisen due to technology (e.g. robots Vs humans), but the motivations of the characters and the situations they found themselves in still had a strong echo in the human condition and the everyday experience of being human.

In my SF story The Buggy Plague, which was set on Mars, I thought I was out there talking about computer drives with terabytes of data storage. That was a little more than a decade ago and we are already there and beyond. Yet hopefully the core story – where an archaeologist tries to stay alive on a planet where man’s own technology has taken on a sentience and will of its own (and avoid a murderer) – still stands up.

Of course it’s far easier to set the story way, way into the future. That way you can be extreme in the technological changes without ever getting caught out (mind you if you are still being read in 2758 I’d take that as a win anyway). Compare that to writing a few decades into the future. Sketching out something like David Brin’s Earth, set fifty years in the future, would involve far more detailed research into trends in technology, energy use etc.

Another way to escape the problem is to make the timeline obscure. You can portray familiar technological elements, with some new twists, yet never spell out the actual date. Just include enough familiar setting elements to bridge to the present.

The story can be set on another planet similar to Earth, where there is the implication is that the technology has been rediscovered, yet perhaps expressed and developed along slightly different lines. This allows the familiar to be placed alongside the new without direct comparison by the scrutinising reader.

The approach that probably trumps them all is to make it clear at the outset that we are dealing with an alternate timeline. One off-hand comment about the Chinese colonies in the New World in the fifteenth century places the story firmly in the nether-zone. From there you can put together just about any sort of technological mix without going off the rails. This also allows you to explicitly give the dates. You can present the world as a direct analogue to current society, without having to worry about getting the technological development wrong. I would have to say I don’t like using this. I tend to be a purist in this way – I like to try and predict our future. But that’s a tough game to play.

So how do you future-proof your fiction? Or do you just follow the story where it leads?

June 20, 2013

Weird Orbits

When I thought about getting somewhere in a spaceship as a 13 year old it seemed pretty simple – just point the ship in the right direction and hit the go button. Most SF seems to feature ships with plenty of power, certainly for interstellar travel it seemed a case of point and shoot.

But travel in the solar system is all about conserving the precious fuel. The latest navigational schemes are all about maximising the efficiency, usually at the expense of the time of travel. Of course we are talking robotic probes here, so preserving the human cargo is not an issue, just the patience of the organisation that sends the probe (and the engineers and scientists anxiously watching it do its thing).

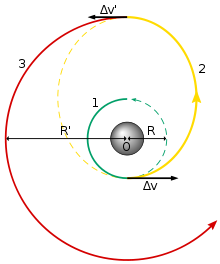

When Apollo 11 went to the moon in 1969, it followed the Hohmann transfer orbit (see below).

Relatively straightforward in concept, this basically takes the ship from one orbit to another orbit (1 to 3), with one half of an elliptical orbit (2) as the intermediate transfer step. This is nice and neat if you have high-thrust engines that can accelerate or decelerate (i.e. for going the other way) from orbit to orbit in a way that’s virtually instantaneous. In reality, you might have lower thrust, so the orbits are changed over a number of timed bursts, gradually increasing the orbit. These lower thrust manoeuvres require more Delta-v than the two thrust orbit transfer, however a high-efficiency low-thrust engine might be able to accomplish them with lower overall reaction mass. This is an advantage for small satellites where reducing the total fuel mass is critical.

The other alternative is to use the slingshot effect. The principle here is conservation of energy. The spaceship uses the gravity of a planet to increase its speed. The planet is slowed down by the smallest of margins, but for very little applied thrust the ship can pick up a real burst of speed. The Cassini probe used this approach when it journeyed to Saturn. It first set off toward the centre of the solar system undergoing two close encounters with Venus, then swung back past Earth and onto Jupiter before turning to Saturn. Again, like the Hohmann transfer that took us to the moon, this is all about swapping orbits via an intermediate orbit. What about just changing directly from one to the other?

There is another subtle approach that is being used to bring spacecraft to their destinations while using the lowest amount of fuel possible. This exploits strange regions of chaos that can occur in areas where the gravitational force of two (or more) bodies cancel out. The most well known of these are the Lagrange points in the Earth-Moon system, where I still imagine the O’Neill colonies spinning away.

This approach exploits the orbits that intersect with these ‘null’ points. Once inside the null point, a ship can apply a very low amount of fuel – and taking its time – cruise out of the zone and straight into a new orbit without having to blast away its fuel in a high-cost Hohmann transfer manoeuvre.

This scheme was used to bring the Japanese space probe Hiten back from Earth orbit to the Moon after it had all but run out of fuel. Edward Belbruno, an orbital analyst at JPL, came up with a scheme that allowed the probe to visit the Moon’s Trojan points (where gravity and centrifugal force cancel out) to examine cosmic dust. The scheme used the L1 Lagrange point.

Astronomers have observed a strange orbital network in the solar system where natural bodies take advantage of the ‘chaos’ in these null zone to swap orbits. One example is the comet Oterma, which was orbiting the sun in 1910, it changed orbit a few times, orbited Jupiter for a while, and then orbited the sun in a new orbit that brought inside the orbit of Jupiter. Then it had enough of that and went back to orbiting Jupiter again, then looped back outside the orbit of Jupiter to orbit the sun again (where it is now). Crazy but true.

Natural bodies seem to have a propensity to ‘change stations’ at these cosmic transfer points. The strange thing is that these points are truly chaotic – there is no predicting what will happen if a body crosses into them. They might emerge in the same orbit, or into one fundamentally different. We can exploit these by forcing the change – using a precisely timed bit of thrust. Of course the down side is it takes longer.

Just think where we could travel in the solar system if some form of ‘suspended animation’ and the length of journey was not such an issue?

Nice to think of these natural orbital transfer points housing space colonies and tourist resorts. Maybe casinos?

June 13, 2013

Aha! Moments in Writing

Thinking back over the years I’ve been pounding away at the keyboard (at the beginning I actually typed stories on Dad’s old police-issue Remington. It wasn’t pretty), got me thinking about moments of key realisation in the writing craft.

I guess for me the first one of these points would have to be understanding the need for true inventiveness. As for most writers, when I started off I wanted to recreate what I loved in fiction. In this case, sword-and-sorcery in a fairly familiar fantasy setting. My first ‘aha’ – triggered by the advice of a more experienced writer – was understanding the need to be original in the worlds I created. That more than anything shaped my later work.

Following that was less of an ‘aha’ I suppose than a gradual understanding of point of view. Again, like most newbies, there was plenty of head-hopping in my early efforts, although to be fair this was more common in the sort of work that was inspiring me than what is on the shelves these days.

Then the sinking realisation that being as good as what has gone before is not good enough – the writing craft moves on.

Next was probably the daunting realisation that just because I was feeling something when I wrote and/or re-read a particular passage of my own work did not mean anyone else would. That opened up a whole issue of writing craft – kind of like realising the solid bridge you were standing on was really a tightrope over an abyss. Evoking something in a reader’s mind was a lot harder than I thought.

There were plenty of others: active Vs passive, ‘show don’t tell’ , ‘direct’ experience through the use of physical sensations in a character, the ever-present struggle to create emotional resonance in the reader.

What were your ‘aha’ moments?

June 6, 2013

Creative Burnout

Having finished off my Urban Fantasy, Distant Shore (my Next Big Thing:)), and sent it sailing away into the unknown, I’m back to working on my Jakirian fantasy series. As usual, starting a new project is like trying to get blood out of a stone. Added to the normal challenge of changing channels is the creative burnout I am experiencing from the massive push I gave Distant Shore in the lead up to completing it. I’ve never put so much into a piece of work. My creative storehouse of energy is doing a really good impression of a hole filled with super-hard concrete. I reach in and just get blank grey.

That’s not to say I’m not making progress. It’s just painfully slow. When you’re firing, and the work is flowing, all those myriad little creative solutions you need to rework prose and rewrite come so effortlessly. Now – not so much.

At the moment I’m just gritting my teeth and hoping that time will allow the old creative engine to crank up again.

How do you deal with creative burnout? Anyone got any ideas?

May 30, 2013

Crowd Sourcing a Space Program – Mars One Colony & Asteroid Mining

Crowd sourcing of funds for new projects is an interesting development for any artist. The approach has been used quite successfully by many writers, although these writers already had a large following to begin with. To get an idea of how far this can go, have a look at musician Amanda Palmer’s ted.com talk The Art of Asking. It’s clear the sort of way-out extrovert/sociopathic personality you need to take this to an extreme – hell I couldn’t do it. But it is fascinating. And the possibilities are there.

What is also interesting is how this concept is being applied to the development of the space industry and also space exploration.

Aspiring asteroid miner Planetary Resources is developing a series of spacecraft designed to study solar-system asteroids. The company has just launched a crowd funding campaign to support the development of their Arkyd spacecraft. The deal is, if you donate, you get to use the Arkyd, including potentially directing the vehicle’s space telescope at your own objects of interest.

Planetary Resources aim to mine near-Earth asteroids for precious metals and water, both for use in space and also to supply Earth’s needs. The company has some high-profile support, including James Cameron and Google-man Larry Page.

Planetary Resources have just launched a campaign to raise $1 million through public funding. They are waiting to see how much support they gather before deciding whether to also public-fund additional Arkyd spacecraft. For $25 you get a ‘space selfie’ a photo of an uploaded digital image of yourself taken against the background of the telescope in orbit. (Your image appears on a screen on the spacecraft, allowing your image to be in the shot). $99 buys 5 minutes of observation time, while for $150 you can point the telescope at any object of interest you choose and receive a digital copy of the Arkyd photo. That’s pretty cool. I wonder if they would let you drive it?

Explorers Mars One want to establish a permanent human settlement on Mars by 2023 – an ambitious timetable in anyone’s book. They recently opened for applications for colonists, so if you’re keen to leave the planet permanently, check out the site. While you’re at it, you can look at the profiles of the 80,000 people who have already applied.

Mars One do not intend to be technology developers, instead proposing to use a suite of existing/proven technologies under licence – such as Space X’s Falcon Heavy launcher, a lander envisaged as a variant of Space X’s Dragon capsule – as well as a Mars transit vehicle, rovers, suits, communications systems etc. They already have an impressive list of advisors and ambassadors for the project.

The Mars One model depends on revenue from donations, merchandising and from broadcasts leading up to the event that will focus on a 24/7 ‘Big Brother’ style converge of astronaut candidates. Opponents of Mars One’s approach compare the Mars One concept unfavourably to reality television, and believe the need for ratings will overshadow safety concerns. I wonder what happens when you get voted off the planet?

You can already by the Mars One T-shirt, coffee mug, hoodie or poster.

What do you think about public-funded projects to get us off the rock? Is this an exciting or frightening development? Should space exploration be left to governments?

May 23, 2013

The Nth Circle of Editing Hell

Ok, for a start it’s not really possible to edit a manuscript an infinite ‘n’ number of times. Sooner or later you have to let the Ugly Baby out into the world. As the old saying goes, “art is never completed, only abandoned”.

I’ve just put the finishing touches to my Urban Fantasy Distant Shore (which was the book I spruiked in my ‘Next Big Thing’). My last monumental push was inspired by the deadline for the Queensland Literary Awards, Unpublished Manuscript Award. The competition is always tough, especially for quirky genre works like mine, but it was worth it to support the QLA and to give myself that last bit of motivation to get the thing up to scratch.

Right now I’m drained. I’ve really put everything into doing the final redrafts on this one. Every damn trick I know is in this baby. Not only that, I’ve pushed myself up that sticky slope of manuscript improvement further than ever before.

The problem is, it’s not enough to just have a good manuscript. It’s got to be best you can do and then some.

For me, this meant getting that extra – uncomfortable – brutally honest feedback. Then working to clarify and streamline the prose. Working on word choice – trying to get that perfect verb. As well as all the usual stuff, like eliminating passive voice, using physical responses and sensations in the character to make the experience more direct. Regulating and mixing up sentence length. Over 96,000 words, that’s a lot of work.

Then after all that, I read the work out loud to myself to check the flow and to eliminate those last errors. You can believe I lost my voice over those two days!

What do you focus on when you enter the Nth circle of editing Hell?

May 17, 2013

Juggling Molecules on Mars

So much of what we come into contact with is made of four elements – carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen – the main elements of living systems. Add phosphorous and sulphur and you have what comprises 98% of all living systems.

The chemistry for juggling these four atoms – C, H, O, N – has been around for a long time.

Engineers and scientists have been confident enough in the chemistry and the various ways of manipulating them to propose various sets of reactions for use in gathering resources out in the vast reaches of space, as part of human exploration. This is part of a wider field of study called In Situ Resource Utilisation (ISRU), which has formed a key part of plans to explore other part of the solar system, particularly Mars, for the better part of two decades.

In the Mars Direct concept Robert Zubrin proposed using the well known Sabatier reaction:

CO2 + 4H2 => CH4 + 2 H2O

To react hydrogen with the Martian atmosphere to produce methane and water – very useful things to have on the red planet. The methane would be stored and kept for use as rocket fuel.

Methane and oxygen are a handy combination. In terms of chemical rocket propellant candidates, the Specific Impulse (Isp) of Methane and Oxygen at 3700 m/s is second only to Hydrogen and Oxygen at 4500 m/s (to convert to seconds of impulse multiply by 0.102).

Meanwhile the water from the Sabatier reaction would be split via very familiar electrolysis reaction:

2 H2O => 2H2 + O2

The idea was that only the hydrogen would need to be transported to the Red Plant. H2 weighs a lot less than CH4, freeing up space and payload for the 6 months transit to Mars.

Various test rigs were constructed on Earth, using analogues of the Martian atmosphere, which has been well characteristed since Viking. Mars has a lot of CO2 – more than 95% of the atmosphere – and a nice analogue of the Martion atmosphere right down to the low pressure could be similated for the rig. The CO2 is initially absorbed onto zeolite (an ever popular sorbent) under conditions simulating the Martian night. During the Martian ‘day’ the CO2 desorbs and passes into the Sabatier reaction vessel with the H2, which is heated to 300C. Reaction then occurs in the presence of the right catalyst (in this case pebbles of ruthenium on alumina). The water from the reaction is condensed out and passed to the electrolysis unit.

Still awake?

OK. Not surprisingly scientists and engineers planning Mars missions were concerned about overly complex systems forming such major part of a critical path.

Current plans for ISRU on Mars revolve around direct dissociation of the Martian atmosphere i.e.

2 CO2 => 2 CO + O2

[BTW if you could pull off this reaction at room temperature on Earth you would be an instant billionaire]

The current Mars Design Reference Mission proposes the production of oxygen on Mars through direct dissociation. Methane will be transported directly from Earth, with the ascent vehicle still using the tasty combination of methane and oxygen in its rocket engines.

So how is the CO2 pulled apart? There are many contenders, all of which uses a lot of energy. On Mars that energy is currently planned to be delivered by a 30 kW fission power system.

The front-runner for CO2 dissociation is thermal decomposition, followed by isolation of the O2 using a zirconia electrolytic membrane at high temperatures.

This system was developed for its first flight demonstration as the Oxygen Generator Subsystem (OGS) on the defunct Mars Surveyor Lander, which would have been launched in 2001 (but was cancelled following a string of Mars mission failures – Mars Climate Orbiter (1999), Mars Polar Lander (1999), Deep Space 2 Probes 2 (1999). That was a bad year. ).

The OGS was to demonstrate the production of oxygen from the Martian atmosphere using the zirconia solid-oxide oxygen generator hardware. This unit was designed to electrolyze CO2 at 750C (1382 F). The Yttria Stabilized zirconia material – once a voltage is applied across it – acts as a oxygen pump allowing the O2 to pass through it and be collected. The plan was to run the unit about ten times on the surface.

As I mentioned there were various contenders for the process. Such as molten carbonate cells, which operate around 550C with platinum electrodes immersed in a bulk reservoir of molten carbonate. Personally, the engineer in me shudders at the thought of trying to manage any sort of molten system that remotely.

The final system for CO2 decomposition used on Mars is probably still a work in progress. It will be interesting to see what develops there.

The fact is the initially proposed Sabatier reactions did not produce enough O2 to react with the methane, so some form of CO2 splitting process was still required.

So there are some things we can do to juggle molecules when we get to Mars.

Is everyone out there looking forward to getting to the Red Planet and grappling with what we find there? Who thinks we should not go? And why not?

May 9, 2013

Planet-Hunting Goes to the Next Level

This really is the age of planet-hunting. The number of confirmed exoplanets now exceeds 800, and there are more than 2,700 other candidates waiting for entry into the hall of fame. When you consider how far away some of these suckers are, it really is astounding.

Up until now we have been able to get estimates of orbit, general size and mass. Combined with knowledge of star type, this has enabled astronomers to place the exoplanets in relation to the ‘Goldilocks’ or habitable zone, where liquid water is possible (seen as a likely precursor for the development of life (as we know it, Jim)).

Now the analysis of these targeted systems has gone to the next level. Astronomers are beginning to install infrared cameras on ground-based telescopes equipped with spectrographs. This will enable tell-tale signatures of key molecules to be detected. One key feature of this work is figuring out ways of blocking the glare of the planet’s adjacent star. NASAs planned James Webb Space Telescope will also use a similar strategy to study the atmospheres of planets a little bit bigger than Earth.

Two factors can improve the view. Young planets have more heat left over from their formation, increasing the infrared signal for the spectrographs. The other approach is to look at planets further out from their stars, helping to isolate their spectra from the star’s light. Of course looking that far out means starting with Jupiter-sized planets, but astronomers hope to be able to refine their technique to allow the atmospheric compositions of smaller – and older –planets to be examined.

The Holy Grail is finding an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone with molecules that indicate the probable presence of life. We might have to wait for the proposed Terrestrial Planet Finder before we can crack this.

Still, it’s pretty exciting stuff!

May 2, 2013

Watching the Asteroids

Asteroids are always intriguing. Little planetoids that fly around the solar system in mysterious orbits, often swinging dangerously close to Earth. It’s that element of the unknown as well as the potential threat to life on Earth that always ensures their popularity.

There is a lot of work going on behind the scenes in modelling asteroid orbits and tracking them. The NASA Near-Earth Object Observations Program – dubbed Spaceguard – detects, tracks characterises both asteroids and comets passing by Earth (anything inside 28 million miles of Earth is regarded as Near-Earth). It uses both ground and space-based telescopes. This information is used to predict their paths, and to determine any potential hazard. At any given moment some of the world’s most massive radar dishes are on the case.

A new space-based asteroid-hunting telescope is being planned. NASA scientists recently tested the Near-Earth Object Camera – a key instrument. That will be interesting to watch for, potentially doing for asteroids what Kepler did for planet-hunting.

One favourite way to get to know an asteroid is hitting it hard with another object (not recommended in personal relationships). Those collisions can tell us a lot about their structural integrity and composition. Trying to get that little probe to actually hit anything travelling at hypervelocity (11,000 km/h or above) is a feat in itself.

Knowing where an asteroid will be, and its structure and composition are vitally important things to know if we plan to move asteroids around or want to explore them for valuable materials.

Potential targets can be quite small – as tiny as 50 metres wide. One little-known complication of creating a scientifically significant impact is that they can also have their own little family of tiny moons orbiting around them. Trying to track down those secondary orbiting bodies can be a challenge, but critical to the success of any ultimate impact.

At least with asteroids you do not have the complication of jets of material firing into space, which you have with comets. These can upset imaging and guidance systems.

One likely candidate is the asteroid 1999 RQ36, which is the target of a NASA mission called OSIRIS-Rex. The currently slated launch date is September 2016, with the ‘landing’ in 2023 (now that’s long-term planning). Not only do the NASA scientists need to co-ordinate the impact, they have to ensure that the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft, with its crucial observing instruments, can monitor the results of the impact from a safe distance. This little craft will do a loop around Mars then close with its target at the rate of 49,000 km/h (8.4 mi/s). Needless to say mission scientists will be executing several deep space manoeuvres to refine its position during its approach. The spacecraft’s own automatic navigation system will take control only two hours from impact, executing three planned corrections at 90min, 30min and 3min from the impactor ‘landing’. At this point the spacecraft will be a mere 2,400 km away from RQ36. Cosmic spitting distance!