U. Cronin's Blog, page 25

June 30, 2013

Short Story: Marbles, Part 2

Notwithstanding the taxonomic complexity of pinning a precise Linnaean genus and species on many alcoholics, diagnosis in my grandfather’s case was quite straightforward: he was a textbook roaring alcoholic. The handle fitted perfectly, described him down to the ground. It was daylight-clear, as plain as the nose on your face, elementary; with drink on board, my grandfather roared — or hollered, or screamed, or yelled, or bawled. The house shook. Windows rattled in their frames. Those not wearing shoes could feel the vibrations through the soles of their feet. Sleepers were awoken. Neighbours stopped to listen. Dogs howled. Peace was breached.

While it was one of the central truths of my young life that grandfather + drink = roaring, it wasn’t an immediate effect. A time-lag was involved. My grandfather wasn’t like the character from Father Ted, who, upon tasting a drop of alcohol, the merest microlitre of libation, instantaneously transforms into a maniacal dervish of a roaring drunk. It wasn’t a question of handing my grandfather a glass of sherry and leaping behind the couch for cover because he’d go off in a few seconds. No, there was a substantial gap between the initial delivery of ethyl alcohol and his transmogrification, a phenomenon which by all accounts required quite a heavy dosage.

Not that we ever witnessed the conversion of my grandfather from stolid, shuffling, beslippered, cowboy-book-reading, crotchety OAP into a septuagenarian Johnny Rotten or Brendan Behan at his most notorious. We got to see the beginning, alright — time zero, when he’d leave the house as meek as a lamb — and the end point of the reaction, when it would have been handy to have the garage converted into a padded cell. But we never saw the mysteries of the transmogrification process itself. This was a phenomenon that happened away from our prying eyes, never in the family home, always somewhere up town. My young mind had no understanding of how the imbibing of large quantities of alcoholic beverages could bring about such a radical alteration of personality and behaviour as was the case with my grandfather, and so my ever active imagination stepped willingly into the breach.

The old black and white movie Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, starring Spencer Tracy, made a considerable impression on me the Halloween of my eighth year. I pictured my grandfather sitting alone in the dark snug of one of his bars. An ashen-faced barman would approach his table, gingerly carrying a long-necked flask containing a green-glowing, foaming liquid, and place it carefully before him. The men would exchange a grim and knowing glance, nod as if to seal some tacit, unutterable contract and the barman would wordlessly withdraw. My grandfather would study the flask for what seemed like an age, the silence in the room only broken by the strange liquid’s blubbing and sizzling and the ticking of an old Guinness clock. He would close his eyes, open them slowly and clear his throat. Then his arm would reach out and a pale hand would grip the neck of the vessel, which he would raise to his lips in a swift, sure and resolute motion, before downing its eldritch contents in a single unhurried draught. Faster than he could manage to replace the empty flask on the table, its contents would be taking hold of him. The eyes of his normally impassive face would grow lunatic-wild and shine with the light of an evil madness and a tumult of weird and frightening expressions would flash across his features. Racked by violent spasms, his entire body jiggling and jerking, my grandfather would try to stand up, as if to flee the small room. His knees would buckle. In his attempt to maintain himself upright he would pull the table over. The flask would crash to the floor and shatter. He would unleash a blood-curdling, animal roar. His back would arc backwards, limbs would stiffen and he would be thrown across the room as if by some unseen force. As he shrieked and howled, the same invisible hand would appear to pummel his body and he would be tossed around the floor like a seagull in a gale. It was as he writhed on the floor yelping and growling in fear and agony that a great change would come over his physique. His body would swell, develop a beastly, inhuman bulk, as if it were not just his musculature expanding as a result of the green potion, but also the very skeleton supporting it. His hands would grow to the size of shovels. The clothes would rip from his back as his shoulders broadened and his chest visibly stretched. His calves would tear through the fabric of his pants, his biceps bursting through his shirt. A coarsening of his features would also become slowly evident. Heavy brows, a low forehead and a prominent lower jaw would all contribute to lending my grandfather an atavistic air. Hair would be seen to sprout from unexpected places.

Without warning, a stillness would come over him and silence would once more reign in the room, the transformation complete. He would lift his near-naked body up off the floor and, planting his hirsute feet wide apart, assume an aggressive, simian crouch. He would tilt his squat, Neanderthal head fully back, open his yellow-toothed maw wide and issue a fierce and terrible bellow that would be heard far beyond the confines of the snug — a strangled, guttural howl, unpleasant to the ears but at the same time unmistakably musical. Listeners far and wide would recognise the opening lines of his favourite song when drunk, ‘Come Down from the Mountain, Katie Daly’.

Outside the realms of my childish imagination, my grandfather’s MO was far more prosaic. Averaging out at about once a week, he would dapper himself up (shave, cut his fingernails, slick back what little hair he had left, slap on some old-codger cologne) and, sometime around late morning/early afternoon, announce to my mother that he was going up town. I’m sure alarms bells must have deafened my mother with their clamour upon hearing one of his usual spurious pretexts for taking off (having some business at the bank or needing to get some fresh cowboy books from the second-hand bookshop), but what could she do? Confine him to quarters? Hide his shoes? Lock him in his bedroom? Neither my brother nor I (at school) nor my father (at work) were usually present at the time of my grandfather’s abscondences — he rarely chose a Saturday or a Sunday to go on a bender — but we were present in the house by the time the penny had dropped with my mother that the old man hadn’t simply been delayed or waylaid; that the real reason ― the same reason as always ― he hadn’t come home for his tea was that he was stuck to some bar stool knocking back pints of porter in one of his many haunts around the town. We could see the worry written on my mother’s face and that feeling of tension and dread would spread throughout the household like a thick November fog. It was an anxious time, a period during which my parents would talk out the various predicaments into which my grandfather could have become embroiled — arguments, brawls, betting on horses, trips to Limerick to the dog track, slap-up meals for six in the Old Ground Hotel for which he would pick up the tab. It was also the crunch time for the making of a very important decision: whether to go in search of my grandfather and drag him out of whatever pub he was in or let him stagger home under his own steam.

June 23, 2013

Short Story: Marbles, Part 1

I sometimes tell people during gaps in conversation and the like that they’re in the presence of an attempted murderer, that in a past life my former self, presented with a terrible stressor in his external environment, arrived at a solution to that stressor which involved killing someone. I study my companions’ reactions, relishing their shocked expressions before dropping the punch line.

“I was eight,” I usually say. “And the problem — my grandfather.”

Sometime between my seventh and eighth birthday, my mother’s father came to live with us. The usual story: his wife had passed on, he was finding it hard to manage on his own, the ticker was acting up a bit, he wasn’t able to get about as well as he used. I don’t know if my seven-and-a-half-year-old self’s feelings were taken into account at the hour of making the decision and neither do I recall being canvassed by my mother and father as to whether I wanted to share our household with the old man. In truth, I probably would have answered no and, certainly, after a few weeks of cohabiting with him, had I been asked for my opinion, I would have made it quite clear I wanted him packed off to his own house once more.

You see, I had never been fond of my grandfather. To me he was just this old grouch we were dragged by the scruff of the neck to visit a couple of times a week. He never gave my brother or me anything, no sweets or toys or footballs, he didn’t have any cool stuff in his house and he never played with us. There was none of this taking you to the park or teaching you how to fish malarkey that grandfathers on TV were always at. You never walked in the door of his house to have a shiny new bicycle or an Action Man thrust into your arms. He rarely even interacted with us, beyond warning us not to touch things or knock things over. In fact, he didn’t seem to have much time for us at all. So you can appreciate how, after a few weeks living with the man, a certain coldness towards him, a frosty ambivalence of feeling, could turn into a definite dislike.

Initially, the conflict was territorial. What had once been a spare room, a kind of play room for my brother and me, was co-opted into being my grandfather’s bedroom, which from then on was off-limits for us (not that we would have wanted to set foot in there anyway). Strange and unwelcome items began appearing around the house: inhalers, boxes of pills, cowboy books, greasy spectacles and combs, razors and shaving brushes in the bathroom, slippers. He bullied us about what programmes got to go on the TV and was usually installed in the comfiest seat in the living room already watching some old folks show by the time we got home from school. Then there was the smell. I know it’s a clapped-out old cliché, but my grandfather did have an undeniable and characteristic fug which hung about him and all his possessions and eventually came to impregnate his bedroom — eau de OAP. I can still conjure up the smell in my memory: a sweet, marmaladey odour with a pronounced meaty, buttery tone. Perhaps it’s a biological verity that young boys are programmed through natural selection to find the scent of older men repugnant, or perhaps it was a genuinely unpleasant aroma to the young olfactory system, but it was usually towards the top of my list of things I disliked about my grandfather. Somehow, the smell focused your beady eye even more closely on the old man and brought other odd details and foibles to your attention, making you dislike him even more; you started to notice the funny way he had of chewing, his annoying habit of tapping while he read, how he always walked with his right hand stuck into the breast of his overcoat, Napoleon-like, and his weird, veiny, transparent skin.

But the principal reason I grew to loathe my grandfather and see his presence in our house as problematic was because of his drinking: he was an alcoholic. Not only that — he was a roaring alcoholic. Now, we Irish have as many terms to describe partiality to drink as the Eskimos reputedly have for types of snow. At the low end of the scale, you can be merely ‘fond of the drink’, a quality that may or may not imply addiction, depending on the personage under discussion. At the other end of the scale, you can be ‘big into the drink’, ‘a martyr for the drink’ or the theologically opposed ‘demon (or divil) for the drink’. Character can come into it: ‘He’s a great (or a wicked or a terrible) man for the drink.’ Calling someone a ‘great man for the drink’ suggests admiration for the man, that it’s a joy and pleasure to be in his company while he’s getting stocious. On the other hand, you don’t want to be around your ‘terrible man for the drink’, whose epithet carries images of a turbulent domestic situation, being fired from work for being drunk on the job, house repossession and so on. It goes without saying that you don’t want to be around your ‘awful baisht of a man for the drink’ at all, at all! Terms such as ‘problems with the drink’ or ‘trouble with the drink’ are usually overheard as snippets of earnest, whispered gossip. There are secret drinkers, inveterate drinkers, hopeless drinkers. Your secret drinker is a dangerous animal, from a health and safety point of view; you happen to be in this fellow’s house when you, being inquisitive of nature, open the medicine cabinet and have a half-concealed bottle of whiskey fall down on the bridge of your nose. Or your secret drinker lady friend asks you to change a light bulb in her utility room and you find half-empty vodka bottles clinking around in the lampshade and threatening to hop out onto your foot. Then there’s all the various modifiers of the A word. There are bad alcoholics, as if it were necessary to distinguish this breed from the outstanding or merely good alcoholic. We have raging alcoholics, whose main occupation, besides filling their bellies with porter and whiskey, is the destruction of bar-room fixtures and fittings after a certain threshold of inebriation has been crossed. And finally, and this system of nomenclature is only admissible in Ireland, where attitudes towards alcoholism and drinking in general are more relaxed than, say, Canada, we have qualifiers placed before the A word that play down the importance of the subject’s addictive behaviour. A number of choice adjectives imply that, while technically under the stringent grading systems in existence in ‘enlightened’ countries such as the aforementioned north American territory your man may be an alcoholic, in reality his consumption and comportment are just about inside the limit of what Irish society considers normal and so he deserves a mitigating modifier. Therefore, we have the mild alcoholic, the bit of an alcoholic and the more formally named, but no-less-of-a fudge-for-that, high-functioning or borderline alcoholic. These are men that hold down regular jobs, are decent husbands and fathers, live unremarkable, humdrum lives, but spend inordinate amounts of their free time in the pub, drinking there every night of their lives before staggering home and pulling themselves out of bed the following day to repeat the cycle.

June 15, 2013

Short Story: The Landing Light, Part 2

Mild enough, he decides, and turns right at the gate, going up the road, away from the centre of town. Never know who you might meet on Abbey Street or O’Connell Street even at that hour of the morning. Around the corner, out of sight of the house, he pauses to light up a cigarette. He’s not a smoker, doesn’t know if he even enjoys smoking, but, just like his nocturnal ramblings around town, the smoking is a sort of quiet rebellion, a private way of meting out justice for the unfairness of her rampages. Clearing the hill at the end of his road, he turns left towards the river and the old, abandoned mills. A car sounds in the distance, a low rumble from the Galway road. He wonders if that someone in the car has been driven from their home into the night just like him. He also wonders if he was older would he go for a spin instead of a walk to get away from the smothering feeling of a becalmed house.

He’s at the wide entrance to the vocational school and, past the Maid of Erin monument, catches the river’s glint in the odd shaft of moonlight that manages to dodge the near-total cloud cover. Suddenly, a movement to his left. A man — old, white-haired, bearded — is sitting on the steps of the school’s doorway. He fights the urge to speed up and pretends not to have seen the man.

“Hey! Young fella! Stop! C’mere!”

The boy thinks about running. The man wouldn’t catch him. Very few people could catch him.

“Kiddo! C’mere!”

He stops walking, turns, regards the man, takes a few paces beyond the school’s open gates towards the porch. He could always run later.

“Whatcha doin’ out this late? ‘Tis no hour for a young lad.”

The man has hopeless, bloodshot eyes and a red, bumpy face. There is a bottle of vodka on the step beside him. Before the boy can answer, the old man speaks again: “How old are you, kiddo?”

“Fifteen.”

“I’ve never seen you before. You’re not out on the streets are you?”

The boy shakes his head.

“It’s a small oul’ town, d’ya see? I’d know you if you was sleepin’ out. We all know each other, us bums.”

The last word he enunciates without any bitterness or irony in his voice, as if he’d come to fully accept his station in life. He eyes the boy’s three-quarters-gone cigarette.

“D’ya have one o’ those for me?”

The boy proffers the open box of his mother’s Benson & Hedges and hands the man his lighter.

“You’re an innocent, kiddo!” laughs the man, not unkindly. “You never give the full box to anyone. Never let anyone know how many fags you got.”

His voice is deep. Scratchy. Throaty. He lights up and gives a chesty cough.

“Here,” he says, and hands back the box and lighter. “Whatcha doin’ wanderin’ the streets anywez?”

The boy ponders his reply.

“I needed to get out of the house for a while. Things were a bit . . . heavy tonight.”

The man sucks on his cigarette.

“Is your father a drinkin’ man?” he asks.

“Something like that.” The boy’s father is a drinking man, the boy thinks, but he’s not the problem. His father is a quiet man — a quiet drinking man. He turns the phrase “drinking man” around in his mind. Tries “drinking woman” for size. He smiles.

“I’m sorry for your troubles, kiddo,” answers the old man. “‘Tis an awful cross to bear, the drink. Me own father was a divil when he had drink on him. He used to beat us black ‘n’ blue. Black ‘n’ blue. I got outa there as soon as I was old enough to work. Then I got fond o’ the stuff meself. An’ look at me now.”

To illustrate his point he nods his head in the direction of the vodka bottle. He mumbles something, takes a drag on his cigarette, reaches for the bottle with the speed of a gunslinger and takes a swig.

“The best thing you could do, kiddo, is get him to stop. Get him off the grog. Talk to him, if you can. That’s what I wished I coulda done; talked to me oul’ fella.”

Later, coming home from the other side of town after trudging a long loop through the outskirts, he thinks about what the man told him. Talk to his mother? As if she didn’t know already that she had a problem? That her problem was also everyone else’s? Ha! You never mentioned, the day after, what had happened the night before. It only made the next rampage worse. Gave her extra ammunition.

“You don’t hand the enemy bullets,” said GI Joe in his head.

No, you cleaned up her mess and kept your mouth shut. And you kept the anger and hurt out of your eyes the next day when she came down the stairs and said “Good morning” at four o’clock in the afternoon.

But you could plant little booby traps and instead of words use actions to show someone how much their drinking was damaging everyone. You had to get them where it mattered. So, tomorrow she would search for her cigarettes and, not finding them, a look would come over her. The boy knew what she’d be thinking: “Was I so bad last night that I can’t remember what I did with my cigarettes?” And when she’d open her purse, the same expression on her face. “Could I have spent all that money in the pub last night?” And her brand new oak kitchen table, her Christmas present to herself, her latest pride and joy . . . The boy had had an idea after talking with the old man. When he got back to the house and the mess and the stale smell of drink, he stood almost ceremoniously before the table and raked its dark, shiny, new surface with a fork, giving it a nice, long, deep scratch. That might give his mother something to think about. The scratch would look up at her every day, like a scar.

June 10, 2013

Short Story: The Landing Light, Part 1

The boy breathed as stealthily as his pounding heart allowed him. The house was silent now, but you never knew. And you certainly didn’t want to draw her on you for an encore. If she was woken from the normally fitful beginnings of her drunken slumber by a sniffle, an intake of breath or the creak of a bedspring, second helpings could be worse than the main course. No, best give her ten, fifteen minutes. Then you could think about clearing your throat or moving around a bit. The boy lay there in his comfortless bed, rigid with alertness, staring up at the ceiling of his bedroom which was half-lit by the orange glow from the landing light sneaking in his ever so slightly open door (no closed doors in this house). He hated that orange landing light. Its being on meant only one thing — that she was on the warpath. It was enough for the click of the latch of the front door to sound and the odious orange light to snap on for the boy to break into a cold, tingly sweat, a fearful, tremulous hypervigilance and for the prayer to no god in particular to start playback in his numb head: “Oh, please just make her go to bed straight off tonight. Oh, please. Oh, please. Oh, please.” It was called a conditioned reflex. He had learned about it in biology. A Russian man called Pavlov had shown that you could make dogs salivate by ringing a bell if you taught them to associate the sound with food. The boy imagined himself to be like one of Pavlov’s dogs, except instead of saliva it was fear, sweat and crawling skin; instead of food it was his mother’s drunken rages and instead of a bell it was that bloody landing light.

He sneaks a glance over at the clock radio on the locker to the left of his bed. “03:14,” glow its red numbers — crude, garish, matchstick stubs of light. I’ll give it till half-past, he thinks, and lies there corpse-still, looking into the shadows and listening — a state he calls Yellow Alert, as opposed to Orange Alert when she is downstairs shouting and pulling the place apart, or Red Alert which means she is coming up the stairs for him or his brother or his father.

Tonight had been mostly Orange Alert. A couple of hours of chair-banging, press-slamming, glass-clinking and ashtray-dropping. There’d been a lot of slamming of the back door; the poor dog had been chased out into the garden a few times to do wee-wees. The boy had heard its whines as it pawed the door and pleaded to be allowed back in. Although she did tend to torment the poor dog when she was on the warpath, most of it was inadvertent. She never shouted at or beat it, no matter how mad- or mean-drunk she was. The dog was probably the only living creature in the house immune from her post-pub attentions. And it got scraps from her sandwich-making exploits to boot.

03:30. The boy slides out of bed as ponderously as golden syrup from the sticky green can in the press in the kitchen. You didn’t want to make noise at this stage and squander all the silence of the last half hour. He knew every squeak and creak the bed and floorboards were capable of making and how to avoid their treachery — ninja knowledge. Not so much tip-toeing as slow-motion stretching, shifting the weight of his body from one foot to the other, the boy reaches his pile of clothes on the study desk near the window and swiftly and silently dresses, careful to mute the belt buckle with his palm as he pulls his trousers on. He was a true pro at this stage. Down the stairs, making the banister take his weight, stepping as close as possible to where the steps met the sides and avoiding the few wonky, rattly boards. On the bottom step, he delicately turns off the landing light and breathes an extended sigh of relief.

“Stand down, men! Code green!” he says in his head, using a Marine sergeant’s voice. “But we’re still not out of the woods yet. Mind how you go!”

Illuminated by the sodium streetlight fractured by the frosted glass of the front door, he gathers his boots and coat from the hallway closet and moves operations into the kitchen.

“It’s a warzone in here, men!” GI Joe says in his head.

“A bloody mess,” says his real voice.

Even in the kitchen’s semi-darkness he can see that his mother has had a real go at tearing the place apart. He purposefully ignores the aftershock of her clumsy, drunken, unfocused anger. There’d be time enough for studying it in the morning and for the usual clean-up he performs before she and his father surface, sometime in the late afternoon. The dog is asleep. He goes over to her basket by the range, gently pats her behind one of her long, woolly ears and whispers: “Poor oul’ craythur. Sorry about all this. You’re on the front line down here. Every night lately.” He sits down beside her, pulls on his boots and laces them up.

“Bloody Christmas,” he whispers.

He catches a whiff of horseradish and salami breath from the lightly-snoring spaniel and smiles ruefully as he buttons his coat. On his way to the back door, picking his way carefully through the detritus of his mother’s midnight feast, after-hours drinking and ranting and raving, he spots something near the breadboard, beside an open tub of dairy spread — his mother’s cigarettes and lighter.

“They’re mine now!”

The back door is unlocked and opened soundlessly and the boy walks out into the mid-winter night.

June 2, 2013

Nails

I’d never cut anybody else’s nails until I was thirty-one years of age. Then, in the space of a couple of weeks, I was cutting the nails of two of the most important people in my life, neither of whom was able to perform this task themselves. At one end of life’s journey was my father, riddled with cancer and possessing neither the strength nor agility to wield a nail clippers. At the other, my newborn daughter whose facial lacerations a day after emerging from the womb demanded the application of mouth to tiny finger and the careful nibbling away at her delicate, but razor-sharp nails. I was struck at the time by the difference between the two sets of nails. My father’s were dry and brittle, almost turning to powder on contact with the metal of the clippers; further evidence of his decline, the cancer-driven weathering of his tissues. My daughter’s were as soft and supple as poplar leaves newly-burst out from their buds, attesting to the health and vigour of her little wriggling body.

It felt strange cutting my father’s nails. Indeed, all the little things I did for him during those last few twilight months of his life were accompanied by complex and conflicting sets of emotions. Whether washing his hair, peeling and slicing a pear (one of the few things he still ate with relish), lifting him up in the bed or linking him as he went for a shuffle up and down the ward, I always felt a mixture of pride and sadness. Pride in myself, that I had become man enough to be of help to my father in his hour of need. Sadness, because I was doing things for him that only months before were well within his capacities.

It never felt strange in the case of my baby daughter. Babies were meant to be helpless. Their fathers were meant to cut their nails, change their nappies, cater for their every want and need.

Just like it’s the tiny sparks of personality in a newborn that delight us the most (a particular way of curling the lip, an adult-like frown or a distinctive gurgle), when a parent becomes helpless and you feel them slipping away it can sometimes be the little things, the tiny scraps of evidence of a greater decline, that upset you the most. In my father’s case, it was his sudden casting aside of a lifetime’s habit of smoking that said more than all the charts and bloods and full-body scans. That and his turning up of his nose at a naggin of Jameson I smuggled in past the nurses! I knew then that his spirit was beating a slow retreat from the battleground of his body. Piece by piece he was ceding ground to the cancer.

Somewhere along the line of that retreat he met my daughter, whose rapid advance gave him great comfort during the six weeks they got to spend together. The day before my father died, we put her into his arms and they both closed their eyes and seemed to snooze for a while. With head softly resting on head, it looked to those of us in the room like grandfather and granddaughter were enjoying some kind of non-verbal conversation, something almost telepathic. What, if anything, was ‘said’ during this spell will always remain for me one of life’s sweet mysteries.

I’m still cutting that little girl’s nails ― and indeed those of her younger sister. But like so many of the small tasks I perform for them, given how fast they’re growing up, it will probably be handed over to their more-than-able management very shortly, following in the footsteps of things they now do without any adult assistance such as getting dressed or showering. Soon they won’t need any help from me and perhaps someday it will be me holding out my hand, like my father before me, and keeping still while one of them gets to work with the clippers.

May 27, 2013

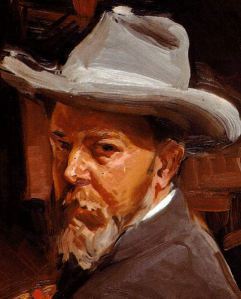

The Sorolla Museum

Every year thousands of tourists come to Madrid to visit its world-renowned art galleries. There are few cities that can match the combined punch packed by Madrid’s big three – the Prado, the Reina Sofía and the Thyssen. But outside of this triangle of museums, all located along the Paseo del Prado and within a fifteen-minute walk of one another, Madrid boasts a number of smaller, less well known galleries. One such hidden gem is the Sorolla Museum.

Though born in Valencia in 1863, Sorolla spent most of his life in Madrid and it is his home – the palace where he painted, sculpted and literally pottered about (the museum has a large display of his ceramics) – that became the Sorolla Musuem a number of years after his death. Even if you never even heard of Sorolla or have no interest in art, the Sorolla Museum is worth a visit. Set in a magical garden with ornate fountains, pergolas and rambling roses, the palace has the air of an oasis of old-world serenity in a modern, hectic city. The house itself is built and furnished in the typical Andalusian style of the nineteenth century and oozes romance, sensuality and joie de vivre.

And then there’s the paintings . . . No one captured the searing Iberian sunshine as truly as Sorolla. You can nearly feel the sea breeze on your face as you stand before his beach paintings while his portraits of his children, whose eyes dance with mischief and joy, seem to come alive as you study them. As the thought hits you that you’re treading the very staircase and the very tiles those children toddled and danced on, you realise you’re in a very special and magical museum; it’s almost like you’re a privileged guest of the Sorolla household.

One of the wonderful things about the museum is that it can be “done” in a couple of hours at most. This and the fact that it has so many nooks and crannys means the kids wont get bored. While not as central as the Big Three, it is located just off the Castellana and within a ten minutes’ walk of the Gregorio Marañon, Iglesia and Ruben Dairio Metro stops. It’s open from 09:30 to 20:00, Tuesday to Saturdays and from 10:00 to 15:00, Sundays and holidays. Entry costs just €3 (but on Saturdays from 14:00 onwards is free!). Check out the museum’s website before going as they often have workshops (especially for kids) on weekends. The only complaint I’d have about the museum is that the security is a bit heavy: I was asked several times not to stand too close to the paintings!

May 18, 2013

Eurovision Predictions

It’s that time of the year again, folks! The European cheese-fest, officially known as the Eurovision Song Contest is on tonight, allowing an entire continent of people to get in touch with their inner Barry Manilow. I have great memories of Eurovision: sitting beside my grandfather watching Johnny Logan sing “What’s Another Year” with a lump in my throat, hearing Liam O’Maonlaí sing “Don’t Go” with a lump in my throat, seeing Riverdance and feeling a burst of national pride with a lump in my throat, and watching Dustin hold two fingers (or is that feathers) up to a bloated, smug audience with (you guessed it) a lump in my throat. These days I would be more likely to have a bolus of vomit in my throat rather than said lump. Eurovision has gone to the dogs. Since they let in all these so-called countries from Eastern Europe (the aim of this article is to be crude and offensive — I’m trying to stretch my palate as an author), a little country like Ireland hasn’t a snowball’s chance in hell of winning. Not even if we got Bono himself to sing our song, put Van Morrison on sax, the risen Rory Gallagher on lead guitar, the Corr girls as scantily-clad go-go dancers and crucify an effigy of Angela Merkel during the middle eight. Christ, it’s not even about the songs anymore (not that the vast majority of these were ever up to much): it’s about packing the stage with as many ethnically-dressed Oompa Loompas as possible, throwing in a couple of jugglers (coz they’re big into jugglers in Bratislava) and having pyrotechnics — and lots of ‘em.

For what it’s worth (and remember I have seen zero coverage of said competition and have no idea what countries beyond Ireland and Spain have made it to the final tonight, so this whole piece is based entirely on ill-informed personal impressions and prejudices) here are the predictions of the Get Behind the Muse jury:

1. The competition will be won by a Nordic or Slavic country.

2. Turkey will not vote for Cyprus.

3. Cyprus will not vote for Turkey.

4. Greece will vote for Cyprus and vice versa.

5. Greece will vote for Serbia and vice versa (Eastern Orthodox connection).

6. Bosnia will vote for Turkey and Albania and vice versa (Islam connection).

7. There will be at least two entries where a man is dressed as a woman.

8. There will be at least two entries where the female lead singer is disturbingly masculine (to the point of, were ‘she’ an athlete, a sex test would be required) and wearing a long, dress with Angelina Jolie-esque split. One of these ‘ladies’ will come from a Nordic country, the other from the East.

9. The French entry will be an avant-garde, post-punk protest song against man’s inhumanity to vegetables (and will be a tuneless pile of cack).

10. The Spanish entry will also be a tuneless pile of cack, but will have the saving grace of including a flamenco-pop guitar solo.

11. At least two countries (not including Ireland obviously) will have bagpipe-like ‘traditional’ instruments and the band dressed in folk costumes.

12. There will be at least two Cossack/hip-hop dance-fusion ‘moments’ from Eastern European entries.

13. Ireland will get less than 20 points, leading to hand-wringing and self-examination on Liveline on Monday.

14. The Maltese (or insert name of other Mediterranean island and so-called country) singer will fall into the category of ‘extremely beautiful but aren’t the eyebrows a wee bit caterpillar-esque’.

15. No one will vote for the UK even in spite of coaxing Bonnie Tyler out of retirement/cryopreservation to ‘sing’ their ‘song’.

17. You’ll miss the ‘best’ (remember: it’s all relative) song while making a cup of tea/taking a cigarette break/having a dump.

18. You’ll have to look up on Wikipedia where exactly the winning country is and there will be comments floating around of “I didn’t even know X was a country.”

19. The singer of at least one Eastern European entry will be the spit of the Lithuanian bouncer from the disco bar down the road.

20. You’ll have forgotten about it all by Wednesday.

May 15, 2013

Vitoria-Gasteiz, Basque Country

I have the goodies in my novel, The Grotto, spend a few action-packed days in Vitoria, where they learn how to use stone circles under Father Morrison’s tutelage, drink coffee in the Plaza Mayor, go on benders in the old quarter and stuff themselves with pintxos and Basque cuisine. O’Malley may or may not have hooked up with a local vitoriana called Ainhoa! In The Grotto, I wanted to get across Vitoria’s relaxed atmosphere, the size and authenticity of its old quarter and the city’s amazing gastronomical culture.

Welcome to Vitoria!

Vitoria-Gasteiz, the official capital of the Basque Country, has suffered (and probably always will) from neither being Bilbao nor San Sebastián. Bilbao —the capital of the province of Biscay and, for many, the real and de facto capital of the Basque Country — is bigger, bolder and brasher than Vitoria — the capital of Álava — while San Sebastián — the capital of Guipuzcoa — is more beautiful, more chic, more sophisticated (and has a beach and an international film festival with attendant celebrities and red carpets to boot). Additionally, Vitoria’s more distinguished fellow provincial capitals (three provinces make up the Spanish ‘autonomous community’ of the Basque Country) will forever be regarded as being more Basque, more authentic, less Spanish. It is always said about Vitoria (and Álava in general) that it has been more subject to Spanish influences down through the years and because of this is somehow Basque Country-lite. I’ve noticed some ‘real Basques’ spit the words Vitoria or Álava through their teeth the way Northern Irish nationalists or Highlanders and Islanders splutter Lowland Scot. The conspiracy theory goes that, post-Franco, the powers that be in Basque constitutional nationalism decided to locate the Basque parliament and associated governmental offices in Vitoria in order to give a shot in the arm to the city’s Basqueness. Regardless of its truth and whether or not it worked (you do hear a considerable amount of the Basque language on its streets, for example), Vitoria continues to be looked down up by Bilbao and San Sebastián and it is still regarded as a kind of Cinderella city. Many Spaniards outside of the Basque Country talk dismissively of Vitoria and some don’t even know who or what Vitoria is!

“If I was going to go on holiday to the Basque Country,” they often say, “I wouldn’t go to Vitoria; I’d go to the real Basque Country.”

Vitoria cityscape from the old quarter.

But these people don’t know what they’re missing. Vitoria is a hidden gem, one of the north of Spain’s best kept secrets. Consistently rated (and scientifically measured, however this is possible!) as offering its inhabitants one of Spain’s highest qualities of life, the city (approx. pop. 240,000) resembles one of those perfectly-designed Sim or Civilization cities. An ideal blend of the old, the new, the urban and the wild, the traditional and the industrial, Vitoria has something for everyone.

The old quarter.

If you’re into history (especially medieval history) and architecture check out Vitoria’s medieval quarter (casco viejo), one of the peninsula’s most extensive and best preserved. Here you’ll find numerous palaces, chapels, narrow, winding lanes and arcades, an ancient cathedral (in the process of restoration and open-to-the-public archaeological investigation) and the old city walls and ramparts. Spend a day roaming its dark, mysterious, narrow, cobble-stone streets. Read a book in a shady walled garden or watch life go by under the watch of the city’s patron — La Virgen Blanca. If culture is your thing, Vitoria has a plethora of museums and interpretative centers, the best known of which is the Artium — a bold and superbly-considered contemporary art gallery, a visit to which always stimulates and surprises. Football? Go see Alavés! (Remember them? 2001 UEFA Cup runners-up to Liverpool!) Basketball? How about Saski Baskonia, one of the Spanish League’s major teams. Into shopping? Wear yourself out exploring the casco viejo and stumbling across intriguing little jewelry and clothes shops or spend a morning in the more modern (Victorian and charmingly fin de siècle!) commercial district. And as for gastronomy . . . !

Narrow street, old quarter.

Vitoria is famous for its food and drink. With part of its province in the south forming la Rioja Alavesa, Vitoria is the place to come if you like your wine. Even the most humble neighbourhood bar will have a selection of reasonably-priced Rioja wines of outstanding quality. And why not chase the wine down with a pintxo (savoury snack or titbit)? It’s a local custom, especially among retired gentlemen of leisure (aka oul’ fellas), to meet up and go from bar to bar, enjoying a glass of tinto (red wine) accompanied by a pintxo in each establishment. This practice is known as chiquiteo and I would highly recommend aping this wonderful local custom — preferably in the old quarter, where the pintxos are unwaveringly excellent (chorizo a la sidra, morcilla, txaka, tortilla de hongos) and the bars range from authentic old codger dens to hip ‘n’ happening cutting-edge cafes to those of the radical Basque nationalist variety. A warning: make sure you’ve nothing urgent planned for the rest of the day, as chiquiteo, (especially if you’re Irish like me or my characters in The Grotto), has the tendency to deflect you from your previous objectives and morph into an all-day session! If you’re not prepared to spend a day tipping away at the wine, no problem: just “do” one or two of Vitoria’s hundreds of pintxo bars. My favourite is the Sokoa on Calle Independencia, which has a baffling choice of pintxos and Rioja Alavesa wines.

The Virgen Blanca.

Moving up the culinary scale, Vitoria has, in keeping with many Basque towns and cities, a love affair with gastronomy and haute cuisine. In general, the emphasis is on Basque cuisine or modern variations on the theme, but you can find any kind of cuisine in the city. Vitoria’s Michelin-starred restaurant is the Zaldiarán on Avenida Gasteiz but there’s also the Marqués de Riscal in nearby Elciego.

The Plaza de la Virgen Blanca.

Finally, if you’re into jazz, Vitoria hosts an internationally-renowned jazz festival. Many of the greats regularly visit the city for the festival, which has been running for over thirty years and takes place in July.

Park bench in honour of some of the greats that have played Vitoria.

April 30, 2013

Eels: 28th of April, La Riviera, Madrid

This was the last night of Eels’ tour to promote this year’s Wonderful, Glorious. 53 dates since February 14, beginning in Santa Ana, California and ending in Madrid‘s Riviera — a 2,500 capacity venue beside Madrid’s Manzanares River and overlooked by the Royal Palace and Almudena Cathedral. The final gig on a tour can go either way: you can have an exhausted band, robotically going through the motions, fixing the audience with 1000-yard stares as they mentally put the rigors of touring behind them and dream of family and sleeping in their own beds or you can have a giddy, excited band that has been forged in the white heat of a world tour and is giving it their all as they drive for the line. Fortunately for a packed Riviera, we got the latter.

Eels’ Mark Everett aka E

From the moment E and the boys hit the stage and launched into “Bombs Away”, we were rocked by an outfit as tight as a duck’s arse and delighting in their performance as much as any band I’ve seen. Speaking of outfits, Eels all wore matching vintage Adidas tracksuits and aviator sunglasses — a look which suggested that these guys meant business, were up on stage for a workout and that us down below better get ready to be taken through the wringer (which we were). The look also gave the impression of a band that was functioning as a unit, a team, and, given the high quality of their output, its cohesion and harmony, those darned (not literally, of course!) tracksuits weren’t just for show. These guys were flying in formation and all their bombs were hitting bull’s-eye. The numerous high-fives, embraces, group hugs and even a wedding ceremony/renewal of vows (yes you read correctly) between E and guitarist, The Chet, attested to the togetherness of this particular incarnation of Eels.

Which brings me onto another thing: audience interaction. These guys had fun with us. And we had fun with them. There was none of that “we love you Madrid, you’re the best audience ever” bullshit you get with a lot of acts (you stand accused, Arcade Fire!). We were treated to E’s wry humour and strangely charismatic self-deprecation, The Chet’s attempts to get cheap applause by using Spanish and P-Boo’s zaniness. They teased us, made jokes about siestas and pretended to be offended when we mock-booed — the kind of stuff you want from a band in between songs. A bit of their personality. Some humanity. A sense of who they are. From the last two bands I saw at The Riviera (The xx and Crystal Castles) we received none of this; we may as well have been watching Kraftwerk in full-on Mensch Maschine mode.

Some words: funky, bluesy, dramatic, hectic, hard, rockin’ — even hard-rockin’! The music was all these things, sometimes simultaneously. Very few of the songs played were of the downbeat or slow variety, bar “The Turnaround” from Wonderful, Glorious, a cover of Small Faces’ “Itchycoo Park” (which I believe they’ve been doing a lot live lately), and a beautiful, chilled, delicate version of “Fresh Feeling”, which sounded like Johnny Marr had snuck on stage to help out with the finger picking. The majority of the material was taken from Wonderful, Glorious with the bulk of the remainder coming from the last three post-Blinking Lights and Other Revelations albums. It’s a sign of how strong E’s songwriting remains that he doesn’t have to stray too far from the current and recent records to fill up an amazing show. Thus, no “Novocaine for the Soul“, nothing whatsoever from Electoshock Blues, and only “The Sound of Fear”, the aforementioned “Fresh Feeling” and “Souljacker Part I” from their pre-Blinking Lights canon. Oh and a brilliant, joyful, bliss-inducing mash-up of “Mr. E’s Beautiful Blues” and “My Beloved Monster”!

This was a show for current fans, not those that dropped the band sometime between Shootenanny and 2013, when the going got tough and E stopped writing impress-your-friends and buy-the-T-shirt songs along the lines of “I Like Birds” or, as he says sarcastically, George W. Bush’s favourite — “It’s a Motherfucker”! If Eels have gotten more difficult, less immediate since the early noughties, it’s because the songwriting has matured. It’s always been reflective in an edgy, sarcastic sort of way, but now it’s just deeper, more layered. The songs demand more of the listener. More listens. More attention. But when an album grows on you, it’s part of you forever. And when you hear those difficult songs live, it’s more rewarding than 1,000 “Novocaines” or “I Like Birds”. If you want “Novocaine” check them out at a festival! And anyway, who say’s “Fresh Blood” with its wolf-howls ‘n’ all isn’t the new “Novocaine”?

So. Final verdict? This long-time (I remember when “Novocaine” and “Last Stop: This Town” sounded like the future!!) fan came away from the Riviera (after a third and very late encore to a half-empty hall and with the house lights on) having been blown away by both the material and its delivery. Eels are one of the best live acts out there. Their commitment to playing live and giving a good show is as clear as the stripes on E’s sweatpants. They rocked my world last Sunday.

April 27, 2013

Basque Woodland

The Basque Country (Euskadi in Basque) straddles the border between southwestern France and northern Spain. If you include Navarre (I’m not going to go into the arguments for or against including it as that would involve treading the minefield of Basque independence and Hispano-Basque relations), there are four Basque provinces in Spain and three in France. (You often see the graffito 3+4=1 in the Basque country, but once more, I’m not going there!) Last weekend we spent a wonderful couple of days in a small village, Galartza, in Gipuzkoa (I’m using the Basque spelling here) and I was stunned by the beauty of the forests we trailed through.

Gipuzkoa, like its neighbour, Bizkaia (using the Basque spelling once more; Biscay in English) has a maritime climate and the woodland plants to be found are very much what you’d expect to come across in an Irish forest. Everyone in the Basque Country tells you how much like Ireland their landscape is, how green it is. But it’s a different green and the mountains are much newer, much sharper. The place has a less gentle and somehow more closed-in feel. And there’s no bogs! And although the symbol that many Basques stick on their cars to let everyone know they’re from the Basque Country is a sheep, I didn’t see half enough sheep to merit comparisons with Ireland!

Below are photos of the landscape and some familiar trees and plants I came across, all examples of the flora that spread to Ireland from the Iberian peninsula after the last ice age. In the forest were plenty of ash, beech, holly, pendulate oak, holm oak, birch, whitethorn, elder and of course black pine.

Whitethorn – Crataegus monogyna

Basque Woods

Basque Mountain House

Holly – Ilex aquifolium

Gipuzkoa woodland view

Beech – Fagus sylvatica

View from Galartza

Unfurling fern

Gorse – Ulex europaeus