U. Cronin's Blog, page 24

September 22, 2013

The Valley of the Fallen

“It’s Franco’s Valhalla,” a wry Scotsman once told me. “You have to go see it.”

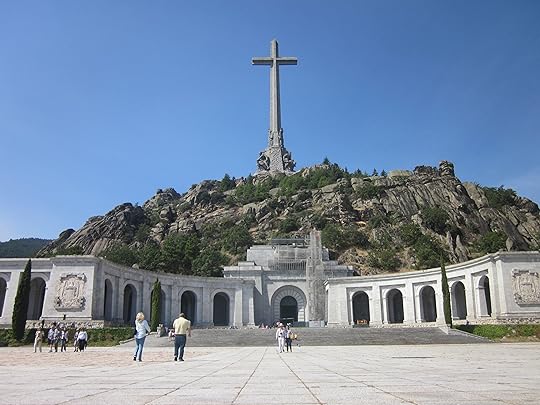

He was referring to the Valle de los Caídos (The Valley of the Fallen), a monument built by the victorious Falangist dictatorship to commemorate those who died in Spain’s bitter Civil War (1936-39). Although “monument” falls well short of describing the place. Its cross (the world’s tallest at 108 meters) can be seen for miles, perched atop a small peak of the Guadarrama Mountains, just outside Madrid. Underneath the cross is a basilica (officially declared so by Pope John XXIII), carved into the mountain. An underground basilica, hewed out of the bare granite over the course of almost 20 years (1940-58) by prisoners from the losing republican side of the war. The formula was: two days’ freedom for one day’s work. One source claims that over 20,000 prisoners were involved in the monument’s construction. Nobody knows how many republican prisoners died on site, but estimations put that number in the thousands.

The Valle de los Caídos cross.

In a typical Spanish way, the Valley is attempting to be everything at once; it doesn’t know quite what it is. Is it a monument, a basilica — or a cemetery? (There are over 40,000 bodies interred in a series of crypts and catacombs off the eight chapels inside the basilica.) Also typically Spanish, the complex is huge. It is said that Franco wanted something on the scale of the nearby San Lorenzo de el Escorial monastery, which was built by Felipe II at the height of his power and represented a bold statement of his empire’s wealth, power and technological advancement. As such, the Valley of the Fallen can be seen as an attempt by Franco to show the world how ambitious, capable and Christian his Falangist regime was. So the entire complex occupies the best part of the valley of Cuelgamuros and consists of: the Benedictine Abbey of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen — built in a similar style to El Escorial and comparable in terms of grandeur and size. The monastery serves as a guest house and restaurant and its monks as the monument’s protectors/caretakers; the aforementioned cross, below which are sculptures of the four evangelists and their symbols; an enormous plaza stretching out before the entrance to the basilica in which one can imagine legions of troops parading grimly during torchlight processions before the approving gaze of el Caudillo; a number of minor monuments scattered around the mountain (the stations of the cross etcetera); the basilica itself.

Valle de los Caídos – the cross above and entrance to the basilica below

The first words you read on the plaque at the head of the long tunnel that leads from the huge bronze doors at the entrance to the basilica’s nave are “Francisco” and “Franco”. Not “God”, nor “Spain”, nor “in honour of those who died in the Civil War”. In the passage’s gloom, as you make your way towards the basilica and feel the weight of the mountain on your shoulders, you get the impression that the basilica is less about religion, less about God, less about commemorating the deaths of thousands of soldiers in a bloody civil war and more about a certain dictator and the cult of personality that surrounded him. Before you enter the basilica, you have to pass a pair of sculpted archangels; bronze, hooded, with swords, nasty, pointed, veined eagles’ wings, larger-than-life and menacing as hell. Their forbidding presence serves as a warning: “any messing from you— any disrespect — and we’ll fly down out of here and stick you!” The basilica is enormous. Football-pitch enormous. 262 meters in length and as high as any over ground basilica. 20,000 cubic meters of granite blasted and torn from the mountain.

The monastery at the other side of the mountain to the entrance to the basilica.

The nave is even more dark and shadowy than the tunnel. There are a series of chapels along its length dedicated to various Spanish virgins. These suffering female archetypes are, bar the image of the crucified Christ on the Alter, the only touch of humanity in the whole place. The rest of the art is warlike, designed to instil fear and make the point that life is a crusade — a war between the forces of good (the Church, the Falange) and evil (the Devil [who features in many of the tapestries] and the Republicanos). Between each of the chapels are a series of replicas of seventeenth century Flemish tapestries whose themes centre on the apocalypse of St. John. Surrounding the alter are massive statues of four archangels, as awe-inspiring, mysterious, glowering and otherworldly as the abandoned temples of Gondor from the Lord of the Rings. Then, fore and aft the alter, are the tombs of José Antonio Primo de Rivera and Franco, respectively, lying underneath a dome of staggering scale (42 meters high by 40 diameter) and featuring the mosaic of Santiago Padrós (the righteous flocking into God’s paradise). And you realise that here is the culmination of the entire project — a fitting home for the architects of Spain’s Falangist “salvation”. Buried underground, away from the light of day, a place to justify the bloodshed, to inspire fear, respect, awe. A warning and a vindication. A burning longboat pushed out to sea. Franco’s Valhalla.

The plaza in front of the entrance to the basilica, Valle de los Caídos.

The Spanish don’t know what to do with the Valley of the Fallen. In a country still divided rigidly along the fault lines of the Civil War — left vs. right, PP vs. PSOE, facha vs. rojo — the Valley is so clearly a partisan triumphalist monument that what to do with it in the context of a country still struggling to heal the still-weeping gash of the Civil War seems like an insoluble conundrum. What can they do with it? Close it down? Impossible: apart from the huge political implications of doing so, the Valley is a functioning basilica of the Roman Catholic Church and a cemetery in which are buried soldiers from both sides. Turn it into a museum with a balanced historical non-partisan explanation and interpretation of the hows and whys of the Valley’s construction? Even the idea of the presence of a museum on-site has been rejected by the Right and the Catholic Church. The socialist government led by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero passed a Historical Memory Act (2007) in which there is an article specifically dedicated to the Valley. Therein is to be found an explicit wish for the Valley’s depoliticisation, mention of the establishment of a body to take responsibility for the Valley’s management and which was to have as its objective the honouring of all of those killed in the Civil War, regardless of whatever side they may have taken. The Act specifically prohibits the enactment of rallies of a political nature on site, especially those glorifying the Civil War or Francoism. To date, nothing has really been done to depoliticisise the Valley. It remains, depending on your viewpoint an embarrassing, offensive or glorious monument to a fascist dictator and his quest for immortality.

The view from the plaza, Valle de los Caídos.

September 17, 2013

The Atlas of the Great Irish Famine

In 1841 — pre-Famine — Ennis had circa 9,300 inhabitants. Ten years (and untold suffering) later, in spite of the influx of thousands of refugees from the surrounding countryside, the town’s population was 7,841: a 16% decline. In Ennis’ hinterland there was a 30-40% decrease in population between 1841 and 1851, with a 45-65% reduction in the number of children under five. Some black spots lost over 50% of their inhabitants.

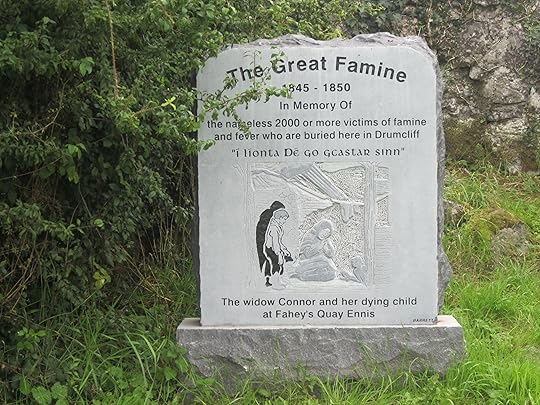

The Famine mass grave in Drumcliff graveyard, outside Ennis.

My mother remembers her grandmother telling her that “there was no Famine in Ennis” (Famine denial was common in the decades preceding the catastrophe). Having recently finished The Atlas of the Great Irish Famine (Cork University Press, 2012; eds. John Crowley, William J. Smyth and Mike Murphy) I would respectfully beg to differ with my great-grandmother. My home town of Ennis in common with a huge swathe of Ireland, west of a line from Donegal to Waterford, was devastated by the Great Famine. During the period 1845-51 the country lost over one million of her inhabitants to starvation and starvation-related diseases and another million to emigration. In the decade after the Famine, another million souls fled the island. The cowed and stunned Ireland of 1860 was a radically altered place compared to the teeming, heaving (but admittedly troubled) country that met travellers on the eve of the Famine. Not only was it a sadder, emptier place, with torn-down cabins, abandoned villages and lonely fields of lazy beds but its culture had been forever transformed: the poorest class of labourers had been decimated, Gaelic culture, on the back foot since Cromwellian times, had been dealt a lethal blow and the Catholic Church managed to turn the people’s misfortune to its advantage to gain for itself a position of prominence that would last until the new millennium.

The Atlas is a weighty tome and even without considering the subject matter, a daunting proposition for any reader. Coming in at just over 700 pages, the decision to read this book is not to be taken lightly, because this is a read you will not enjoy. You may feel a certain satisfaction upon snapping it shut for the final time, having made it all the way to the epilogue, which ends with a quotation from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable, but the journey from the preface to there is a Calvary. A scourge. Harrowing. Distressing. And here, by the way, language begins to fail, to let us down. Because words cannot describe the horrors of the Great Famine. It’s ravages are beyond indescribable and cannot be contained within the pages of any book. But you get the idea that if any book could have a stab at doing written justice to the Famine, the Atlas is that book.

The Atlas is divided into a number of sections within each of which are chapters written by experts in their respective fields. There is a chapter devoted to each of the provinces and, interestingly, those on Ulster and Leinster belie the assumptions that the Great Famine was exclusively a West of Ireland phenomenon. Large parts of Leinster were as affected as areas west of the Shannon and I was astonished to learn that Presbyterians in Ulster were disproportionately affected by hunger and evictions. As you would expect from a book with “atlas” in the title and with heavy involvement from UCC’s Geography Dept., there is a plentitude of maps throughout the book. Many of these are high-resolution (down to townland level) and allow one to trace the course of the Famine in a given district. The maps, many of which are complex and require careful study, are always accompanied by a clearly-written explanatory text and fleshed out in detail in the main text. On top of the maps, the book is brimming with figures — photographs, paintings, manuscripts (especially and very movingly letters from emigrants and those they left behind) and illustrations and printed text from contemporary sources (newspapers, magazines, periodicals, posters, public notices etc.).

The Famine is presented to the reader both from the macro, helicopter view and the micro, ground level view. Hence there are chapters on wide issues such as “The colonial dimensions of the Great Irish Famine” or “The cities and towns of Ireland, 1841-51″ and chapters on very local and specific matters such as “The Famine in the County Tipperary parish of Shanrahan” or “Ballykilcline, County Roscommon”. Significant space in the book is devoted to what is called “the Scattering” ― emigration. Here, the maps reveal a deluge of humanity from Irish ports to the US, Canada, the UK and Australia. So comprehensive is The Atlas that there are a number of highly interesting sections on aspects of the Famine that are merely touched on in other books. We have a section on “Witnessing the Famine” which details contemporary accounts of the disaster and contains a chapter on the Famine as recorded in Gaelic manuscripts. There is also a section on “Remembering the Famine” which deals with folk memories of the Great Hunger. Many of these are harrowing, for example the account of a witness’ childhood memories of men walking along the road carrying what he thought at the time to be “bundles of sticks” on their backs and burying them in the ditch but which his adult self came to realize must have been corpses. A particularly interesting section deals with the legacy of the Famine, in which it is presented as the most significant event in shaping modern Ireland. Almost every event and trend since 1845 can be looked at in the light of an event that wiped Gaelic culture off the map, broke the spirits of the people and depopulated the island. For example, Ireland today would probably have a similar population to Holland and a completely different urban structure, were it not for the Famine. Imagine a Dublin of two million people, large cities with close to a million inhabitants dotted around the country and a confident, majority Gaelic culture.

An indication of the value and usefulness of the Atlas is the sheer detail of what it revealed to me about my own area before, during and after the famine.

What was the nature of Ennis and Co. Clare society, culture and economics pre-Famine? Beginning with language, between 70-80% of the people in and around Ennis would have spoken Irish (1851 census) while this figure would have been over 80% for the Burren and Loop Head areas. Ennis and the county in general had very little of a manufacturing base during these years (20-30% of the economy) and so was almost totally dependent on agriculture and its vicissitudes. In 1841, 44% of the town’s inhabitants lived in 3rd and 4th class housing (one-roomed mud cabins and slightly larger shacks, respectively) and 39.5% of people were chiefly dependent on their own manual labour. Only 15-25% of population in Ennis area could read and write in 1841.

Famine memorial stone, Drumcliff graveyard outside Ennis.

What was life (or what passed for life) like in the town during the famine? Ennis being a workhouse town, there was almost certainly a huge influx of the destitute from the surrounding countryside. These would mostly have been Irish speaking. With access to workhouses severely limited, these poor labouring families would have congregated in roadside agglomerations (alongside mills and quarries, in cabin suburbs) or colonised spaces such as the Fair Green. Pressure on the original workhouse (which was not among the workhouses “upgraded” in the 1847 programme) forced the opening of a number of auxiliary workhouses in the town. By 1851, the total workhouse population was 4,481. Ennis had a county infirmary, a fever hospital and numerous dispensaries. It was common for the poor to pawn whatever few possessions they had (including the very clothes off their backs) in order to scrape together a few pennies for food. During the Famine, there were pawnshops in Ennis, Kilrush, Miltown Malbay, Lahinch, Ennistymon, Killaloe, Tullow and Gort. Such were the conditions, that a temporary fever hospital was opened in Ennis during Famine. As the Famine progressed, there was general unrest and food riots in Ennis and its surroundings; grain barges on the Fergus were attacked, requiring a naval escort to protect the boats going from Limerick to Ennis. Let us not forget there was a Young Ireland rebellion in Ireland in 1848. William Smith O’Brien (1803-64), a Protestant nationalist who was elected MP for Ennis in 1828, was an early advocate of Repeal and he later joined the militant Young Ireland movement. He was convicted of high treason for his part in the failed rebellion of 1848 and transported to Tasmania.

One author, Ciarán Ó Murchadha in writing about the Famine in Clare says that in 1847 the influx of poor people into the county town of Ennis became a torrent: “evicted, famished and pauperised individuals from the parishes around flocked towards the Union workhouse and when refused entry then huddled in crowds outside the gates or haunted the streets and alleyways in search of shelter. Clare, like all the Munster communities, was seeing, first the gradual, and then the rapid acceleration of the collapse of its society”.

What was done to relieve Famine in Ennis and Co. Clare? More than 50% of the populations of the county’s essentially Irish-speaking Unions were in receipt of some form of relief for at least two years between 1847-51. Among the Famine relief projects set up in the county were the building of the County Courthouse in Ennis, which was designed by local architect Henry Whitestone. A huge project was the draining of the River Fergus, and which was one of the biggest public works schemes undertaken in Ireland during the Famine. It was started under the Drainage Act of March 1846 and lasted into the mid-1850s. The Ballyhee Cutting, three miles north of Ennis, half a mile long and in places over forty feet deep through limestone rock, is the most impressive surviving aspect of the scheme. In mid-July 1847, when all the local road schemes had been closed down, the Fergus scheme was the only source of relief work and employed 600 labourers.

Clare County Courthouse in Ennis – a Famine relief scheme.

Relative to other parts of the country, emigration from the Ennis union was relatively low (rates were somewhere in the region of 10-12.4%), a possible explanation being that the population was too poor to afford passage money. Those who did emigrate, however, had the option of doing so from Clarecastle or Kilrush. There were numerous cases of forced emigration. An infamous and well documented case was that of the girls transported to Kangaroo Point, Australia — one of three districts which formed the emerging town of Brisbane during the late 1840s and early 1850s. The orphan girls who arrived to the colony on the Thomas Arbuthnot included sixteen-year-old Mary Fitzgibbon from Ennis. These girls lived, worked and married in the pioneering surrounds of Brisbane. Many other girls from Clare’s Unions were also on this boat: Mary Carigge, Mary Connolly, Mary Fitzgibbon, Alice Gavin and Catherine Smith. Margaret Stack, then 14 years of age, came from Ennistymon. Her parents Peter and Bridget were both deceased. She was employed by Mr. Charles Windmill of north Brisbane at a wage of £6-9 per year but these indentures were later cancelled after she appeared before the Bench for neglecting her work. On September 4, 1852 she married James Smith a carrier and bullock driver and had twelve children. She died on November 21, 1919. Her sister, Mary also arrived in Moreton Bay on the Irene in 1858.

And the post-Famine landscape?

Through depopulation, many of Clare’s towns literally disappeared, including Spancelhill, which once was a vibrant town but ceased to be between 1841-51. (A “town” was an agglomeration of more than 20 houses that had a population less than 500.) Well-establish towns declined substantially: Kilrush was as large and important as Ennis in 1841. Like many medium-sized towns (pop. 5000-10000) the famine almost wiped it out. Land ownership patterns were radically altered. There was an over 40% reduction in the number of holdings in Clare between 47 and 55, with the poorest of the poor driven from the land. 10-12% of properties auctioned under the Encumbered Estates Court between 1849 and 1855 were in Co. Clare. 6.3-7.8% of Ireland’s evictions between 1846-52 happened in Clare. 7-14% of the evicted families in Ireland between 1849 and 1852 belonged to Clare. Smaller holdings were consolidated and farm sizes increased. The class structure of society was also radically altered by the Famine. There was a huge decrease in Ennis of families dependent on “vested means” and “direction of labour” during 1841-51 — circa 500 “well-to-do” families. Notwithstanding this, it was the fourth-class-house-dwelling, manual labouring class (Irish-speaking, illiterate) that were most affected in Clare during the famine.

Mícheál Ó Raghallaigh, a Gaelic scribe from northwest Co. Clare details the extent of the devastation wrought by the Famine across the “kingdom” while also recording the number of dead in his own parish of Kilmanaheen in Corcomroe: “Many people died everywhere in the kingdom. Fever and sickness overcame them as a result of hunger and that is how people in this country died. More than a thousand fell in this parish in three months.”

So read the Atlas and weep. It is a work of true scholarship and a worthy effort at providing detailed information to the lay student of history. It was a most difficult read, but one I am satisfied to have worked through.

September 8, 2013

To Be Surprised At Oneself

One of my favourite phrases within the extensive lexicon of Irish begrudgery (e.g. “’twas far from frappuccino’s yer wan was brought up” or “shur they didn’t have an arse on their trousers, that crowd”) is “to be surprised at oneself”. As in: “look at Mickie Murphy over beyond. Since he sold that site to the council and built the oul’ block of flats on High Street he’s surprised at himself.” What I like about the phrase is its sophisticated intertwining of two separate attacks on (a) the subject’s background; and(b) his character. This two-pronged instrument of (character) assassination suggests on the one hand the subject’s humble origins and on the other his or her inability to “deal” with the new found elevation of their circumstances. There’s also the implication that the subject has been a somewhat passive agent in his or her rise (and is therefore “surprised” at his or her new station in life).

Your typical candidate for being surprised as him or herself would come from a working class or small farming background. There’d be talk of them having been “dirt poor” or “not having a pot to piss in” as children. At school, they wouldn’t generally have dazzled their teachers and fellow students with brilliance (“Mary was always a bit of a gobdaw at school; she wouldn’t have passed a worm”) and nor would they commonly have received third-level education. Up until the point of their upward rise they would have been modestly employed in manual labour, clerical work or farming. In their town or village or neighbourhood they would have moved in social circles “appropriate” to their rung of the social ladder. Blue collar stuff — no involvement in the operatic society or membership of the Rotary Club, but perhaps a lot of pub-going and GAA-centred activity. Then, out of the blue, our subject would start their own little business, which would initially have been a “nixer” — moonlighting, a second job, done outside of normal working hours in parallel to their regular job. Friends, neighbours and family would at first have been sceptical. “That’ll never take off. Shur what does Paddy know about installing TV aerials?” would be a typical comment. As Paddy’s business would grow and he would leave his original job to dedicate himself full-time to his TV aerial business the scepticism would be replaced by mild and reluctant admiration. “Fair play to Paddy. I thought he was only wasting his time. But look at him now.” Soon his business would grow to such an extent that Paddy, now with several if not tens of staff under him and the money flowing into his bank account, would begin to attract serious, premier-league begrudging. “Look at that jumped-up Jack, swanning around in his Merc and with his fancy suits, thinking he’s somebody. He’s let the bit o’ money go to his head.” But in a sense, Paddy would be his own worst enemy in fuelling this envy. Along with the aforementioned top-of-the-range German automobile and the sharp suits there’d be the new house on the other side of town with all the bells and whistles (six en-suite bedrooms, a conservatory, a back yard hot-tub, a basement boys’ room replete with bar and snooker table, a home cinema, a kitchen that Nigella would kill for) the gadgets, the conspicuous consumption, the holidays to far-off and unheard-of places. All of the above would give rise to unrelenting, intense and mean-spirited gossip and begrudgery — but nothing above the ordinary backbiting any successful man or woman receives in Ireland. Paddy, however, would cross a line. As part of a process of reinventing himself, of acquiring upper-class respectability, he would begin to distance himself from his old circle of friends and his former interests — a process referred to as “becoming fierce grand”. Instead of betting on horses, Paddy would start socialising with the “horsey set” i.e. the doctors, solicitors, big farmers and remnants of the Anglo-Irish Ascendency that engage in the expensive and exclusive pastime of fox hunting. Instead of fishing, he would take up golf, securing membership of an exclusive club. Instead of going to hurling or football matches, he would develop a new-found interest in rugby. He’d no longer frequent his local pub but start socialising in cordon bleu restaurants, the golf club and the wine bar. His photograph would regularly appear in the paper in the context of Lions Club or Soroptimist balls, where he would be referred to as a “local entrepreneur”. This perceived betrayal of his roots would have consequences for Paddy. His life within the locality would now be under intense scrutiny. Any movement or action would be the subject of gossip and speculation. Any slip-up or failure (especially on the marital front) would be greeted with malicious glee. “He had it coming to him,” they would snigger. Similarly, business set-backs. “Shur, he’s gotten too big for his boots!” Other failings, particularly bizarre or out-of-character behaviour would be explained by the catch all: “Ah shur. That fella doesn’t know what he’s at anymore. Isn’t he surprised at himself?”

In a country where great importance has always been placed on social cohesion and solidarity among family and neighbours, the accusation that someone has distanced themselves from their roots to such an extent that they don’t know who they are anymore i.e. they are “surprised at themselves”, cuts very deep. In four years of living in Spain, where, admittedly begrudgery isn’t quite as Olympic a sport as in Ireland (envy and bad-mindedness does exist but is quite different from Hibernian begrudgery), I haven’t come across a similar expression. Nor does the expression seem to be used in other anglophone cultures, where success and social mobility isn’t viewed with quite as much suspicion.

August 18, 2013

Boycott and the Royal Academy of Spanish

The Royal Academy of Spanish (Real Academia Española) has been in existence since 1714, with its role being the standardisation and codification of Spanish across the world, from Madrid to Manila and taking in the vast majority of the South American continent. There are many who would see this body as excessively conservative, especially in the area of approving the use of loan words, in particular from English. It does seem like the Academy takes perverse pleasure in blocking the entrance of words (take “blog” for example) into their dictionary. It would also seem as if they are being Cnut-like in attempting to stem this flow of words from English in today’s world of the internet and 4G and globalisation and what have you. (You could say they are acting like Cnuts!)

There is something typically Spanish (top-down, undemocratic, paternalistic, authoritarian) in the Academy’s efforts to keep their language pure and as free of foreign influence as possible. And when it becomes inevitable that a word receive the rubber stamp and be squeezed into the dictionary it seems as if it is done so grudgingly. Very often the word’s spelling is changed, probably to disguise its foreignness, make it seem more Spanish (or possibly out of a malicious desire to tinker with the offending word). Take “boycott” for example.

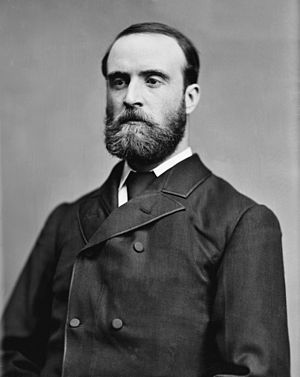

Charles Stewart Parnell. Library of Congress description: “Hon. Chas. Parnell of Dublin, Ireland” (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

How the word entered the English language is well documented. On September 19, 1880, Charles Stewart Parnell speaking in the Square in Ennis (a five minutes’ walk from my childhood home, by the way) made, in the context of the Land League‘s campaign for land reform in Ireland, his famous speech calling for hostile landlords to be shunned.

When a man takes a farm from which another had been evicted you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him, you must shun him in the streets of the town, you must shun him in the shop, you must shun him in the fairgreen and in the marketplace and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in a moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of his country as if he were the leper of old, you must show your detestation of the crime he has committed.

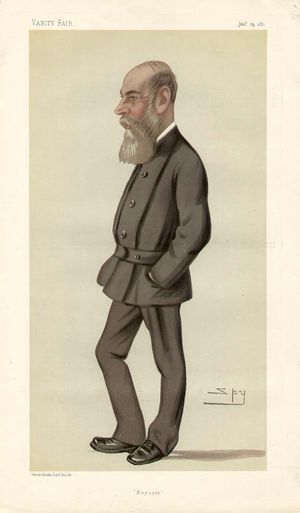

Parnell’s words were first put into action a few weeks later in Co. Mayo against the Earle of Erne’s English land agent, Captain Charles Boycott. So ostracized by his tenants and the local community was Captain Boycott that he could get nobody to work his fields. The 50 politically motivated Orange Order members from Cavan and Monaghan that volunteered to help him needed police escorting to and from Castlebar each day and the estate was given army and police protection. One thousand policemen and soldiers were involved in the entire operation. The Land League gained a great victory with Parnell claiming at the time that it cost over one shilling for every turnip dug. Parliament in Westminster clearly couldn’t devote the same the same resources to every land dispute in a country boiling over with a conflict known as the “Land War” and so the likes of Captain Boycott were forced to negotiate and conciliate instead of evict. Thus, the tactic of boycotting was born.

Caricature of Charles Cunningham Boycott (1832-1897). Caption read “Boycott”. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Boycott (spelt “boicot”) first appeared in the Academy’s dictionary in 1927 (almost 50 years after the word fist began to be used in English and presumably many years after Spaniards and South Americans spoke of el boicoteo and boicoteando [the boycott and boycotting]). While a 50 year gap between a word’s going global and its appearance in a dictionary may seem excessive, defenders of the Academy would claim that its purpose is not the registering of ephemeral usages in Spanish, but to protect a united Castilian language and prevent national variants from becoming incomprehensible to other Spanish speakers. Let’s hope “crowdfunding” and other new terms will make it into their dictionary before 2050!

Real Academia Española building, Madrid, Spain. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

As a final aside, I currently live at about the same distance from a roundabout named in honour of the Royal Academy of Spanish as I used to live from the Square in Ennis, so in a way the word’s journey from boycott to boicot is mirrored by my own.

August 11, 2013

The Gate of Enlightenment

When Madrid’s Gate of Enlightenment (Puerta de la Ilustración) was inaugurated in 1990 it was intended to be a new gate for the twenty first century, having the same symbolic importance as the city’s other celebrated gates — La Puerta de Alcalá, La Puerta de Toledo etcetera — which have, over the centuries, gained iconic, let’s-make-these-into-a-fridge-magnet status. There’s no risk of any enterprising knickknack manufacturer turning the Gate of Enlightenment into a fridge magnet: Madrileños are not particularly fond of it and, as a consequence, tourists are unaware of it.

The Gate of Enlightenment got off on the wrong foot. Its construction was tabled as part of the project for the completion of Madrid’s first ring-road, the M30, whereby the extant western and eastern sections would be joined, squaring the circle, as it were. The northern section of the M30 wouldn’t be any run-of-the-mill motorway, however. It wouldn’t be like the grim, utilitarian western and eastern stretches built in the 1970s. No; there was talk of the new northern section having leafy boulevards, parks, fountains, pedestrian crossings and sculptures — lots of them. At least four on the scale of the Gate of Enlightenment, which was to be Spain’s largest ever sculpture.

As construction on the M30 dragged on and on and the disruption to the lives of north Madrid’s inhabitants continued, the citizenry became less and less enthused by the grand plans for the road. They just wanted an end to the noise and the dust and the earth movers and diggers and detours and delays. They just wanted their road. Eventually, plans for three of the four sculptures were shelved, with only the Gate of Enlightenment surviving the cull. As its gleaming arcs grew slowly up from the ground, it became a symbol for the people’s discontent with the entire M30 project, their totem for complaints and recriminations. The gate was pointless, expensive, impractical, they said, a further source of road closures and detours. When one of the huge concrete beams on which the sculpture is supported fell through the earth and pierced the tunnel of line 9 of Madrid’s metro (thankfully not while a train was going through, but still managing to shut that section of line down for weeks), it was the final nail in the coffin of the Gate. From then on, it was viewed with hostility and dislike. It was finally inaugurated in 1990 with minimal fanfare. No television cameras. No radio. Minimal press reportage.

The Gate has never recovered from its prenatal unpopularity, which is a pity, because it is a bold and brave statement. Its two lines of interlocking arches (13 in each row) shine in the Spanish sun like the spires of Camelot. Sculptor, the Valencian, Andreu Alfaro, spoke ambitiously of a gateway that would welcome motorists to a the city with a dazzling display of baroque modernism. The arches are undoubtedly modern. Technology was pushed to the limit to realize Alfaro’s design. The sections of stainless steel were manufactured in Spain by a civil engineering company, sent to Italy to be polished and bent into shape, welded together on site and filled with concrete as they went up. After more than twenty years of exposure to the elements and the pollution from the thousands of cars passing beneath each day, there isn’t a scintilla of rust or tarnishing in evidence. And there certainly is something baroque about the curious and pleasing manner a descending line of semi-circles interweaves into a reciprocatingly ascending line and the effect this produces when the sculpture is viewed from various angles. The biggest arch is an impressive 23 meters high and 41 wide and each line is 33 meters long.

Ask your average Madrileño on the street today and you will find no spark of fondness for Alfaro’s arches. On top of the sculpture’s unfortunate beginnings, the fact that the Gate of the Enlightenment is located on a roundabout on the M30 — one of Europe’s busiest ring-roads and on which thousands of motorists stew on a daily basis in rush hour traffic — does not help. As for the Gate’s becoming a tourist landmark; it is too far out from the city center to feature on the guides. If a single tourist has ever taken a detour from the typical Paseo del Prado/Gran Vía/Sol/Royal Palace route to view the arches, I would be astonished. So a sculpture intended to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Puerta de Alcalá is today a criminally anonymous and ignored structure that stands on a roundabout on the M30 and under which pass a citizenry at best ambivalent and indifferent its presence.

August 4, 2013

The Concierge: still going strong in Spain

In the same way I feel uncomfortable being addressed as “sir” (there’s something simperingly deferential — feudal even — in its use that offends my belief that all men are equal), living in a building with a concierge also sets the egalitarian in me squirming. For a myriad of reasons, I find the idea of the concierge a distasteful anachronism. Do I need someone to open the door for me so I can step out onto the street in the morning? Do I need someone keeping track of my comings and goings throughout the day? Do I feel better about life safe in the knowledge that there someone sitting behind a desk in the foyer of our building “taking care” of things? Does it make me feel good about myself that there’s someone in a uniform doffing the hat to me every time I pass, someone theoretically below me on the social ladder who is there to serve and obey?

In spite of technology rendering many of his (I have yet to come across a female concierge) traditional functions obsolete (the security camera, the intercom), the concierge is still a mainstay of Spanish city life and not just as a relic associated with pre-Transition (to democracy in 1975 following General Franco’s death) apartment blocks or “exclusive”, snobby developments. In the Spain of today, the concierge (portero or concerje in Spanish) can be as readily found in recently-constructed complexes as those from the 70s and with equal probability in humble, middle-class buildings as in the tower blocks of the rich. Why are the Spanish so fond of the concierge?

Firstly — security. The Spanish are, if not obsessed, then, at the very least, highly preoccupied with security. The average Spaniard seems to believe there are hoards of burglars stalking the streets waiting for the opportunity to slip into their homes and divest them of their most valued personal possessions. Excessive (in my humble opinion) measures are taken to deter robbers: ground and first floor windows have bars over them; most modern developments would be what we call “gated communities”; the average sleepy village, where the last crime logged was the non-payment of a dog license in 1987, is locked down like Fort Knox. In this context, there exists the notion that a building with a concierge is safer than one without.

Secondly — it is undoubtedly true that a building with a concierge runs smoother than one without. Instead of a property management company or an officer of the comunidad de vecinos (the representative body of the individual homeowners within an apartment complex) making sure the cleaning ladies are keeping the halls and stairs bright and shiny and staying on top of things like putting the rubbish out, if you have a concierge there on the ground, day-in day-out, everything tends to work significantly better. Many concierges are quite the handyman and, even though it may not officially be written into their job description, they are only too delighted to oil a squeaky door or fix a leaking pipe.

Thirdly — concierges have a huge social value. In an aging society (Spain has one or Europe’s greyest demographics) the concierge and the little services he can perform for a building’s aged residents is an agent of considerable good. Helping a widow carry her shopping, reading the water meter for an old man with arthritis or signing for a parcel while someone is out are some of the many small but significant acts of kindness a concierge might perform over the course of his working day. For some elderly residents who live on their own, the typical shooting-of-the-breeze conversation with the concierge may be the only contact they have with another human being that day.

Finally — there is a certain snob value in being able to drop into a conversation that you have a concierge. While not so much the case nowadays, in the past, saying you lived in a building with a concierge meant something. Thus, along with post codes and square meterage, having a concierge is one of those many badges used to denote social status.

So, regardless of whatever I might opine, it looks like the concierge will form part of the fabric of Spanish urban life for some time to come. There is no difficulty filling open concierge positions. It’s not a badly paid job on the scale of things and, apart from the long hours (our concierge, Rufino, puts in five ten-hour days and a half day Saturday), is viewed as a good, steady job, something of a cushy number. In most cases it’s a job for life — Rufino has been concierge in our building for thirty years, practically all his working life, and will probably continue “being our building” until he reaches retirement age. Concierge work suits a certain kind of person — someone who doesn’t mind having a lot of time on their hands, someone who can whittle away the long hours on side projects. (I know someone who studied for a degree in linguistics while night concierging and our Rufino plans his budgie breeding programme during down time.) I’ve often wondered how much writing one could get done as a concierge, that maybe it wouldn’t be a bad thing for me to don that uniform and . . .

July 28, 2013

Melons, Magazines and Lottery Dreams: Spanish Street Vendors

The Spanish live their lives on the street – and who could blame them? They have the weather for it. Except when it gets excessively hot or rains the odd time, the streets of Spanish towns and cities are crammed with people and are joyful, noisy, bustling places, filled with lively conversations, laughter and movement. Is it any wonder then that your typical Spanish street is packed with street furniture, from benches to fountains to advertising hoardings to the many and varied stalls of street vendors?

A typical Madrid kiosk.

The press kiosk (quiosco) is a universal feature of the Spanish streetscape. In a country where the British/Irish concept of the corner shop doesn’t exist, the kiosk fulfills many of its roles. As well as selling the daily press and magazines, kiosks stock a wide variety of trinkets and convenience items. In tourist hot-spots, you can buy postcards, fridge magnets, Spanish flags and the like. Your local neighbourhood kiosk will sell you cigarettes, bus and metro tickets, sweets and soft drinks. Kiosks are family businesses and you sometimes hear of the more venerable stalls having provided a livelihood for four of five generations. In Madrid at least, they tend to open at six or seven a.m. to catch the early morning commuter/rush-hour crowd and generally stay open until lunch time (two o’clock-two thirty), while reopening again for a couple of hours in the evening. The majority will have shut up shop by seven/seven thirty.

An ONCE booth.

Another regular on the Spanish street is the ONCE booth. ONCE (Organización Nacional de Ciegos Españoles) is a charity for the visually impaired that gains much of its income through the selling of lottery tickets and their stands are everywhere — and I mean everywhere. The Spanish don’t bet on horses or greyhounds or football matches (you just don’t find betting shops in Spain) — but boy do they love their lotteries! You’ll find an ONCE booth every couple of blocks in the bigger cities, each operated by its own visually-impaired vendor. When I first came to Madrid, I once tried to orient myself using an ONCE booth as a reference point (thinking that something so unusual as a stall selling lottery tickets must be a rare enough landmark in a city) and became hopelessly lost, but not before realising that I had been mistakenly using several close by booths as the same landmark!

Our local rogue lottery ticket trader!

Despite the ubiquity of the ONCE booths, there are plenty of independent (and sometimes illegal) street traders of lottery tickets. I’ve included a photo of one of these rogues who operates in our neighbourhood.

It is quite common to find florists’ stalls on the streets of Spain. Many of these are run by gypsies and do most of their business at specific times of the year such as All-Saints Day (when almost every Spaniard brings flowers to their loved ones’ graves), Mothers’ and Valentine’s Days. It appears that many shut up shop for the summer (at least in my barrio), because it has proven impossible to find one unshuttered for the purposes of taking a photo for this article!

Ice cream stall.

With the arrival of summer, ice-cream booths, which have been removed and put into storage for the winter, reappear. These are franchises and a vendor will only deal in the products of one company (Nestlé, Frigo, Kalise). Besides ice-cream, these stalls will sell you ice-cubes, minerals, sweets and cold, cold water. If ice-cream vans exist in Spain, I have yet to come across one; these booths seem to occupy their niche.

Melons anyone?

Another summer visitor to the streets of Spain is the melon stall. You can buy fresh, high-quality and reasonably-priced melons and watermelons from these guys from mid-May until the end of September. Most of these stalls tend to be run by South American immigrants these days and many are the property of co-operatives of growers. The wonderful thing about them is their guarantee, along the lines of “if the melon isn’t good when you get it home, Mrs., bring it back and I’ll give you another one.”

Churros and chocolate.

In autumn, the roasted chestnut sellers hit the streets along with churro (a fried dough confection somewhat like a straightened out doughnut) and hot chocolate stalls and the smell of smouldering coal and scalding-hot oil fills the air. It seems like you can track the season’s progress by looking at who’s selling what out on the street. A question that exercises my kids is where, for example, does the ice-cream man go during the winter? I often speculate that perhaps in another neighbourhood he stands warming himself by an oven of glowing coals shouting “chestnuts for sale, chestnuts for sale” and dreaming of the summer where he can sit in his cool and shady stall bagging ice-cubes and checking the temperatures of his freezers.

July 21, 2013

The Grotto and the Sun Goddess

Don’t be put off by the name. Nicker, meaning “the rabbit warren” (an coinicéar in the original Irish), is a very unique place. Along with Glencolmcille and Leacht Benáin, half way up Croagh Patrick, the grotto behind Nicker parish church is one of the most spiritual and mysterious places I’ve ever been. The immediate surroundings of the grotto are enveloped in a cone of silence; there’s no birdsong, the wind doesn’t disturb the branches of the trees and there’s not a peep from the nearby roadside or fields. It seems as if time is standing still.

The Lourdes grotto behind Nicker church.

I was directed there by a retired geology lecturer acquaintance of mine.

“A mini Giant’s Causeway,” he called it.

“The grotto is built on an old volcanic stack,” he explained. “The basalt cooled into the same hexagonal forms as up in Antrim. It’s less extensive. Less spectacular. But worth a visit if you’re in the area.”

Hexagonal rock formations at Nicker.

Taking him up on his recommendation, I did pay Nicker a visit and he was right — it was worth a visit. But however curious and other-worldly the roughly hexagonal columns of matt-black rock were, it wasn’t just these that piqued my interest or gave me the impression I was somewhere unique. Nor was it was the Lourdes grotto itself — an ambitious monument, considering the tiny village which it serves. In spite of its sheer size and scale — the way it was built into the hillside’s bare rock, the cave underneath it, the crucifixion scene on the hilltop above, the sculpted stations of the cross leading up and down from it — it wasn’t this that arrested me during my visit to Nicker grotto. What took my breath away, what startled and surprise me, was the great sense of calm, transcendence, of being at one with my surroundings that the location instilled. I’ve been to many grottoes in my time (I have more than a passing interest in grottoes), many holy places, and very few had every moved me to a state of mind even approaching what I felt that day. So I did a bit of digging.

[image error]

“Like the Giant’s Causeway.”

It turns out Nicker is located in a very special part of the world — a part of the world that has long been a centre of ritual and worship, both pagan and Christian. Nearby Pallasgreen (in Irish “Pailís Ghréine“, meaning stockade of Gréine [Grian in English]) derives its name from the ancient Irish goddess, Gréine. Can we make the bold assumption that the palisade in question was some sort of ceremonial structure similar to the wooden henge unearthed in the south of England recently? To the southwest of Nicker is Knockgrean hill (the hill of the Grian — Cnoc Gréine in Irish). Who was this Gréine? Meaning “sun”, it is thought that Gréine was either the sister of the Irish pre-Christian sun goddess, Áine, or one of her alternative manifestations. Another theory runs that, because of Áine’s association with midsummer rites, it is possible that Áine and Gréine may share a dual-goddess, seasonal function. The year’s “two suns” may each be represented by one of the sisters: Áine, the light half of the year and the bright summer sun (an ghrian mhór), and Gréine the dark half of the year and the pale winter sun (an ghrian bheag). It is intriguing that the Nicker “complex” is only about seven from Áine’s hill, Cnoc Áine (Knockainy).

So, could it be the case that the day I visited Nicker, I picked up on something of the ancient spirituality of the area, some residue of the centuries of rite and ceremony that must have taken place there? The sites at Nicker Hill, Knockgrean and Pallasgreen must have had central roles in the lives of the men and women of the entire region in pre-Christian times. Perhaps in the place where the grotto now stands, or on nearby Knockgrean or below in Pallasgreen, grand rites were celebrated during the winter solstice, with crowds of people travelling from all over County Limerick and beyond to participate? Is it possible that something of the magic and power of these rites survives in Nicker? Or maybe Nicker Hill and surroundings always exuded a special energy and it was this (or the strangeness of the geological formations) that inspired our ancestors to centre their sun worship around it?

Just as with thousands of pagan sites around Ireland, from holy wells to holy mountains (Croagh Patrick used to be the mountain of the god, Crom Cruach, before Patrick staked his claim with his forty days and forty nights of fasting), Nicker was appropriated and sanitised by the new religion, Christianity. A church was built below the volcanic stack that held such fascination for our ancient ancestors and then a grotto was built on the stack itself. So what we get is a new layer of belief and ritual being constructed on the old one, without the latter ever having being fully obliterated. This is what made the Celtic Church so unique and allowed religious practice and the folklore of Ireland to have such a pagan undercurrent all the way up to historical times. What says it all for me is the fact that Nicker is in the civil parish of Grean — a parish named after a pre-Christian goddess.

July 15, 2013

Short Story: Marbles, Part IV

My brother and I weren’t more than a minute in bed, when we heard the front door gently shut and the Escort being cranked up in the driveway; my mother had decided to embark upon a second foray into the wilds of the Ennis evening pub scene. (A note to the young reader: it was quite common when I was a boy to leave children older than six to eight in the house on their own for a few hours. My parents often left my brother and me completely unattended while they went shopping or to a funeral or even to the pub at night after we’d been put to bed. In those days there was nothing unusual in this practice. Please don’t be left with the impression that, just because there was an alcoholic grandfather in the household, we were a dissolute, degenerate lot and that my brother and I were only dragged up!) A short time later, we were awoken by a loud crash coming from the downstairs hallway. My grandfather had returned! Once more, the old fox had eluded my parents and while they were dashing from pub to pub up town he would be sleeping off his intoxication in his cosy bed! Except on this occasion my grandfather must have had the munchies. Instead of staggering upstairs, flopping onto his mattress, falling into a deep sleep and rocking the house with his snores until mid-afternoon the next day, he made a windy-day beeline for the kitchen. Now, as an example of one of those peculiar rules that are welcomed far more by the governed than by the issuing authorities, my brother and I had been instructed to under no circumstances get up and try to deal with a drunken grandfather if my parents weren’t present. This was fine by us. We had even less desire to set our eyes on a drunk grandfather than on the sober, daytime one we normally went out of our way to avoid. No matter what he got up to downstairs or on the way to his bedroom (singing, banging, clattering, bumping, cursing, coughing, hawking or, of course, roaring), the few times he arrived home when my parents were absent, my brother and I stayed put and schtum in our beds. This time, however, there was such a commotion emanating from the kitchen that we had no choice but to forsake our safe, warm beds and investigate.

Quite high in the mix of sounds coming from below was the barking of our old dog, Max, a portly, lazy cocker spaniel, who was characterised by an almost reptilian lethargy. He was usually comatose in his basket beside the range in the kitchen from early evening until we got up at eight o’clock, and outside this schedule could only be roused if tempted with a morsel of his principal concern in life — food! My grandfather must have done something quite terrible to have disturbed the creature from his slumber. More out of concern for canine than human (in truth we liked the dog a heck of a lot more than the old man), my brother and I crept down the stairs and snuck a peep into the kitchen. We immediately saw the cause of Max’s agitation. My grandfather had somehow fallen into his basket and appeared to be stuck there! With one hand on the rail of the range, he was attempting to pull himself up, but, through a combination of drunkenness, the oval shape and high sides of the basket and the dog’s barking and snapping, he was unable to do so. In his other hand, my grandfather held a bite-marked block of Cheddar cheese. Behind him, the door of the fridge was wide open, letting all the cold spill out onto the lino (a mortal sin in our house!). The penny dropped! The old man had staggered into the kitchen, opened the fridge, pulled out a block of cheese, at which he proceeded to nibble, lost his balance, fell down on top of the dog, who must have squirmed out from underneath him, shocked and annoyed, and let the whole neighbourhood know of this fact through sharp, indignant barking. We closed the fridge, appeased the dog, pulled my grandfather to his feet and helped him up the stairs. He still had the cheese in his hand as he lay down on his bed.

That was it for me. That was the final straw, the declaration of war. It was one thing to cause worry and stress to my poor, long-suffering mother, to send my parents scurrying off into the night on a fool’s errand, consigning my brother and me to an early bed, to stagger in blind drunk at an unearthly hour roaring the words of some God-awful come-all-ye, waking the whole household and causing lights to flicker on in bedrooms across the road, to endure the queer looks of the neighbours and the taunts of their children the next day. But to upset the poor dog? To half squash the craythur, disrupt its precious slumber, drive it from its warm basket by the range? Have the helpless, confused and frightened animal — a softie of the doggy world — heckles raised, barking in the middle of the night, when it wouldn’t normally stir even if the Hamburglar happened to pay the house a visit? This was just too much; the old man had to go.

I cooked up a plan over the next few days and waited patiently for Saturday to come. My scheme required me being present when my grandfather awoke sometime around midday and, because of the small matter of school, this was only possible during the weekend. Even though designating Saturday as my D-day meant sacrificing an entire morning’s play on the road with my friends in order to keep watch on my grandfather’s movements, I could hardly have chosen to bump him off on a Sunday. Wasn’t any sin, no matter how slight, amplified in its wickedness for having been committed on the Lord’s day, and wasn’t my prospective sin likely to weigh heavily enough on my immortal soul already?

On that Saturday morning, in spite of my nervousness, I tried to go casually about my normal routine. In any of the books I’d read or TV shows I’d watched, all the best criminals breezily lived what looked like a regular life while preparing the most hideous of crimes. I went downstairs in my pyjamas, let the dog out to do its business, had a hearty breakfast in front of the television, washed, got dressed, read a little and then, about an hour before the old man was wont to rise, took out a quantity of toys (soldiers, Lego, armoured cars, tanks and marbles) and proceeded to make war in the hallway, with the last five or six steps of the stairs being the high ground the German forces were attempting to take from the severely outnumbered Allies. I crowded the stairs enough with Afrika Korps and Marines to compel my mother to warn me to have it clear by the time my grandfather surfaced and add: ‘We don’t want him breaking his neck on the stairs, do we?’ A few minutes before the bells of the Angelus sounded, I made a big show of moving operations to the other end of the hallway, to the rug inside the front door, and received a ‘Good boy’ from my mother. Now, I would be off the hook; whatever happened from here on in would be seen as an unlucky accident and the half dozen marbles — black crystal bowlers — that I had carefully positioned on the stairs’ fourth and fifth steps and which lay camouflaged within the pattern of its carpet would be seen as an unfortunate and blameless oversight on my part rather than malice.

I heard the creaking of floorboards above me. The old man was up! His footsteps took him to the bathroom. Down in the hallway, a wide arc of German paratroops pinned the few surviving Marines against the legs of an old chair. The toiled flushed and I heard water running. A German captain went down and his men began to lose hope. The bathroom door opened. A few bars of ‘The Banks of Claudy’ at the top of the stairs. More Germans went down. The blue-grey figures began to retreat. Out of the corner of my eye I saw him reach the booby-trapped steps. He lowered his right foot onto the fifth step then put his weight on it as he prepared to take the next step downwards. The slippered foot slid from under him. ‘The Banks of Claudy’ was replaced by an involuntary yelp. He wobbled, like in the cartoons I used to watch, and began to fall, head first. I forgot all about my soldiers to study the plunge I’d been planning all week. The smile that had begun to spread across my face quickly did its own retreat, however. Just as it appeared that my grandfather would go careering down the stairs and make a fatal — or at least hospitalisation-worthy — landing against the tiles of the hallway, his right arm made a grab for the banister. His fall was arrested. The whiplash from his momentum caused the banister to shudder and my grandfather to be thrown harmlessly onto his backside. My mother raced out of the kitchen to see my grandfather rooting under his backside and producing a black sphere about half an inch in diameter.

‘Marbles,’ he remarked.

My mother looked over at me and I hoped and prayed that the disappointment on my face might appear to her like contrition, but I was left guessing, because she just shook her head and went about helping her father to his feet. I gathered up the retreating soldiers and said in my best German officer accent: ‘Ziss mission hass been a severe failure. You vill pay ze consequences!’

I didn’t make any further attempts on my grandfather’s life after that. He died in his sleep about six months later, going on his weekly bender right up until the end. Most of the friends and acquaintances to whom I have told this story express nothing more than mild shock and polite amusement. It is as if this type of amoral and borderline psychotic behaviour is to be expected in children. I recognise myself that the incident is not something I am at all ashamed of. On the contrary: every time I see children playing with marbles on the street (which isn’t very often nowadays), I feel proud of that boy. While his methods were crude and wicked, they were also decisive and direct, and I admire his unabashed attempt to put an end to an intolerable situation that had defeated the grown-ups around him.

The End

July 7, 2013

Short Story: Marbles, Part 3

Both approaches had their advantages and their drawbacks. While deciding, at the risk of inducing indigestion, to spring from the tea-time table while the rashers were still literally sliding down your gullet in order to trawl through all the pubs in town in search of my errant grandfather may have seemed like the plain and obvious strategy to minimise the damage (both self- and collateral) likely to be brought on by his latest tear, this was not always the case. To start with, Ennis in those years had an inordinate number of pubs for its size. If we estimate the population of the urban district to have been circa fifteen thousand in the mid ’80s, then it may surprise you to learn that the town boasted (again, literally: Ennis dwellers, similar to the inhabitants of other rural towns, most famously Listowel, used to boast about how pubtorially well-endowed their town was) over sixty pubs. Close to seventy if you counted hotel bars and stretched the urban district boundary a little to include pubs like The Halfway House on the Clare Road.

Now, this fact, this snippet of trivia concerning Ennis’s recent past, would not have presented a problem to my parents as they zipped around town in our little chocolate-brown Ford Escort had my grandfather confined his drinking to one or two or even half a dozen of these establishments. But my grandfather was promiscuous regarding his choice of watering holes. While there were indeed pubs in which you were more likely to find him than others, his choice of hostelry followed no logical pattern or system that my parents could ever discern. Therefore, you could go looking for him in a pub he had spend the whole day in during one of his recent benders, only to find that he hadn’t set foot in the place all afternoon and, on top of that, neither sight nor sound of him had been logged in any of the neighbouring pubs either. On the other hand, you could, on a whim, stick your head in the door of an establishment which you had heard my grandfather grandly declare his resolution to never set foot in, only to spy him up at the counter surrounded by cronies and having a fine old sing-song or a discussion about the merits of a particular racehorse when the going was soft.

Add to the above my grandfather’s propensity for crawling from pub to pub when on one of his benders, and, once again, doing so in a seemingly scatty, non-linear fashion, and you have on your hands a topographical (and temporal) problem that puts Euler’s Seven Bridges of Königsberg in the ha’penny place. Thus, you could be stopped at the traffic lights in Carmody Street, having just come from a fruitless raid on the four bars at the top of O’Connell Street — O’Dea’s, Brandon’s, Moloney’s and D’Arcy’s. Your next target is the Banner Arms at the corner of Lower Market Street — a long shot, but you have a hunch. Unbeknownst to you, your quarry has just emerged from the still shadows of Fawls, opposite the cathedral, and as you hastily park the car in the market, is making his way towards O’Dea’s, now officially ticked off your list.

And so, you could have the situation where, after bolting your tea, jumping Batman-like into the old Ford Escort, racing around town like Basil Fawlty in search of Peking duck and zipping in and out of bars like Benny Hill in search of a very different kind of bird, you arrive home with a distinct lack of pickled granddad in the back seat. Worse still, you arrive home without said sozzled septuagenarian, a gut-wrenching sense of defeat, hopelessness and frustration tearing at you, only to find the prodigal OAP sitting cross-legged on the couch, nonchalantly watching the nine o’clock news, nicely (i.e., on a one-to-ten scale of inebriation, a two-point-three-three recurring), but not drunk. He looks up at you and smiles wanly. You’re fit to eat the head off him, rip it clean off, even with the kids watching, but he disarms you with a statement that is pitched perfectly between reasonable and pitiable.

‘I met a man. An old friend. The wife’s just died. Emphysema. ‘Twas a slow, lingering oul’ death. Sur’ I couldn’t leave him drinking on his own. Ah, poor, oul’ Billy. And Mags. Shockin’!’ he says miserably and takes the fight out of you completely. You imagine that the kids can see you deflate like a burst football.

In spite of the lack of 100% guaranteed success associated with the snatch ‘n’ grab strategy and the fact that, on the occasions when my parents did manage to hit the jackpot and catch the old coot in flagrante delicto, he tended to get ornery (creating quite a scene between bar stool and car), it was entered into far more often than the alternative laissez-faire approach. Beyond the obvious merits of dragging him out of the pub after just four or five hours’ drinking instead of double that, the seek and capture tactic had the extra benefit of helping preserve my grandfather’s dignity and safeguarding whatever remained of my family’s good name. On those occasions when my grandfather made it home under his own steam, the whole town (or at least those citizenry that happened to be at large on the town’s main thoroughfares as he veered and wound his way homewards while roaring singing at the top of his voice) couldn’t help but learn that he had been on the lash. Not to mention the neighbours! As strangled words and slurred phrases of ‘The Croppy Boy’ or ‘The Cliffs of Dooneen’ rang out on our little road and reverberated off the chimney tops, windows and walls of the neighbouring houses, you could see the net curtains twitching, sense the mocking glee emanating from dimly-lit sitting rooms. ‘The oul’ fella’s been at the quare stuff again!’ you imagined them saying. ‘He’s a real feed of drink on him this time!’ Or: ‘Horsing back the pints in O’Deas’ again, the fool of a man!’ If, however, you got him out of the pub and into the car, he generally piped down by the time my father steered into the driveway so that only the most vigilant and nosey of neighbours would witness him being linked in from the car to the back door.

It was in the aftermath of one my parents’ failed missions up town in the Escort that I hit upon the idea of doing away with my grandfather. That fateful evening in late spring, they’d driven around town not once but twice, desperately hopping from pub to pub. As usual, when it became clear that the old man hadn’t merely gone up town for a few stamps, but had disappeared into Ennis’s parallel universe of pubs, lounges, bars, locals, taverns, watering holes, ale houses, ramblers’ rests, hostelries, drinking dens, boozers and shebeens, my mother had press-ganged my father, after a quick bite of tea for the working man, into turning round the old Ford with an alacrity that would fill the hearts of any Ryanair ground crew with pride, and flying up the Club Bridge towards the Square. An hour later they came home empty-handed ― OAP-less! ― my mother’s face a roadmap of worry and concern. For the next few hours, until we were skedaddled off to bed as the weatherman said Oíche mhaith, she was the very definition of ‘on edge’.

There was much pacing, repeated pulling back of the curtains to facilitate peeping out and similar openings of the front door (as if this would somehow speed the man’s return from whatever devil’s crossroad of a bar he happened to be making a show of himself in). There was chain-smoking and compulsive tea-making to accompany the smoking. There were sworn oaths: ‘If he comes home roaring drunk this time, I swear to Jesus, he’ll never ramble up that town again.’ There were threats: ‘I’ll feck all those rotten oul’ cowboy books of his in the fire if he doesn’t come in that door right now!’ And also firm resolutions about future conduct, with reference to my mother herself: ‘I’ll clip that oul’ buzzard’s wings for him. From now on he’s grounded, I’ll make sure of that’; to my father: ‘And you, Pat, you’re going to have to be tougher with him from now on; no more acting the eejit for him anymore’; and to my grandfather: ‘Oh, he’ll ship up or shape out after this, I’m tellin’ you!’