U. Cronin's Blog, page 23

December 1, 2013

The Kids Are Alright

(Photo credit: occhiovivo)

In the English-speaking world it is a great badge of shame to be still living with your parents as you approach you late 20s/early 30s. I remember the raft of hand-wringing articles that sprang up a couple of years into the recent crisis about college graduates forced by straightened times to move back in with their parents. It was like the world was ending for both parties. Journalists even came up with a name for these unfortunates — boomerang kids. In the Mediterranean world in general, and Spain in particular, there is no such shame. It has never been frowned-upon for adult children to remain living at home with their parents until they themselves got married, and now, with the economic crisis seemingly deepening by the minute, the situation is getting drastic: 80% of young adults under the age of 30 still live with their parents. What are the reasons for this anomalous (to our American/Northern European eyes at any rate) situation?

Let’s talk about those of a cultural nature first and then go onto the economic factors. The Spanish family is famously strong. It is the glue that holds society together and the foundation stone on which the state itself is built. If it weren’t for family unity and solidarity, Spain would have succumbed to widespread social unrest a number of years ago. You’ll hear no complaints from Spanish parents (especially the long-suffering Spanish Mother) along the lines of having the grown-up kids under their feet or wanting a bit of peace and the house to themselves in their old age. Spanish parents adore having their twenty- and thirty-something children around. And they can’t do enough for them. The Spanish Mother being the Spanish Mother (only too delighted to cook, clean, dust, wash and iron for any number of close relatives), the grown-up kids living under her roof receive higher levels of service and care than if they were to relocate to the Ritz in the Paseo del Prado. Typically, adult children are not expected to pull their weight around the house. They are discouraged from pitching in with the cooking or cleaning or other chores; allowing your children to help at home would be a sign of weakness and laziness on the part of the parents. On the children’s part, they see nothing wrong with the arrangement. In Spain there just isn’t the same idea of fleeing the nest as early as possible (me and most of my friends left home at 18, for example) as in other countries. As long as they have the freedom to come and go and if all their friends are doing it why shouldn’t they?

Perhaps being on the receiving end of a pampering at home might just be the only break this current generation of Spanish young adults gets. Times are tough for them. They have no work — over 50% of them are unemployed (this figure hits 80% in some regions). Those that do work are paid a pittance — the average wage for the 18-30 group is €13,600 per annum. They wait longer than their peers in other countries to start their first job (including part-time or weekend work, 23 is the average age). Contracts are short-term and part-time. Spanish young adults are spending more time than ever in higher education, which means they are more highly skilled than ever, but which also means that when they do finally secure employment they are more overqualified than ever. All of which means one thing: whatever about lacking the motivation, they don’t have the cash to put into a house-share.

Perhaps if living with your parents at 28 years of age was as much of a mark of looserdom as in other countries, Spanish kids would have a by-hook-or-by-crook attitude to leaving home as did most young adults I knew when I was young. And perhaps the social acceptability of being unemployed and living at home with your parents would be lessened. At present in Spain, there are so many young people in the same boat that the stigma of being on the dole and living at home that should drive a young person to entertain measures such as starting one’s own business, retraining or even emigrating is absent — something which may explain the net inward migration of 18-30-year-olds into Spain last year. It seems Spanish kids just don’t want to leave the nest.

November 23, 2013

The National: 20th of November, Palacio Vistalegre, Madrid.

El Palacio Vistalegre, Madrid. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Three songs into the set, guitarist Bryce Dessner announced to the crowd that they were “warming up now” and he didn’t mean it in a musical sense. It was a bitterly cold night in Madrid and the Palacio Vistalegre, an old bullfighting plaza, which, although roofed, is essentially open to the elements, was as inhospitable as the freezing warren of streets around it. That the National made the crowd forget all about the icicles dripping from their noses and their frostbitten feet is a testament to the raw power of this veteran band. It was appropriate that The National played in such a taurine setting; there is something of the bull’s elemental energy about front man, Matt Berninger. He prowls the stage like a corralled toro bravo, raging and flailing, his strong baritone ringing out at times like the bellow of a wounded beast. The rest of the band are no slouches either. What surprised me most about seeing The National live was how unrestrained they are. They can be as heavy as anyone when they want to (something that doesn’t come across on their records), building songs into wailing and crashing crescendos. Aaron Dessner‘s lead guitar is much more prominent live than on disk and it turns out the guy’s a virtuoso. His adornments and occasional wall-of-sound solos give the songs a very different feeling live. He’s my new guitar hero!

I went to the concert wanting to hear “Fake Empire”, “Mistaken for Strangers”, “Bloodbuzz Ohio”, and, with a bit of luck, “Conversation 16″. These are songs that have gotten under my skin over the last few years, songs that mean so much to me by now they are almost part of who I am – and indeed part of what we are as a family, with my little girls knowing the words of “Bloodbuzz”. I wasn’t disappointed. But it wont just be memories of strident and passionate renditions of these that I’ll be taking away with me. Songs from the new album, “Trouble Will Find Me”, such as “Demons”, “I Need My Girl” and “I Should Live in Salt” shone brightly in the Palacio Vistalegre and have me putting on the album time after time to be blown away once more by these gems. As a sign of how solid The National’s back catalog is, on top of the aforementioned stand-out moments, the band pulled more than a handful of oldies out of their hat (songs from “Alligator” and “Cherry Tree”) and it was probably “Sorrow” and “Afraid of Everyone” that were my favourite moments from the concert.

The band did the slower and quieter songs like “I Need My Girl” with a sensitivity and subtlety that contrasted brilliantly with the raucous raging of their angrier numbers. Sometimes they achieved both effects in the same song – “Afraid of Everyone” built beautifully into a distorted howl. The pair of trombonists they had with them lent a richness and texture to many songs, notably “Squalor Victoria”. The trombonists also seemed to be a focus for Matt’s between-vocal exhortations and comments, with the tall, bearded singer frequently leaving centre stage to check in with them. Towards the end, we were treated to Matt’s usual sally into the crowd. There was no harm done, although he did pinch someone’s beer!

The concert finished with a heartfelt “Vanderlye Crybaby Geeks”, and saw the band coming forward to the edge of the stage and singing with us in a way that reminded me of a sing-song at an Irish wake. It seemed for the duration of this serenade that the National and the crowd were one, that the band were making a statement about the nature of the so-called divide between artist and audience (something, I think, Matt’s forays into the crowd are meant to show). The National left us sated – and wanting for more. It was a great, great concert. They have the tunes, the lyrics (“You wouldn’t want an angel watching over you/surprise, surprise she wouldn’t want to watch”), the sound, the musicianship and a great attitude. There was no question of them going through the motions or fulfilling a contract with slick professionalism. They were putting everything on the line in the Palacio Vistalegre, just like the bullfighter stepping into the ring and Matt and the boys were on a serious bloodbuzz.

November 17, 2013

Madrid’s Winter of Discontent

Piles of rubbish on a Madrid street during the street-cleaners’ strike, Nov 2013.

It’s beginning to look like winter 2013 will be Madrid’s Winter of Discontent. When the street cleaners have been on strike for over a week and the bitter wind is whipping at the piles of rubbish and fallen leaves and every day it seems like someone else is going on strike or marching or picketing, you know you’re not living in a happy city. There are rumours the bus drivers will be out soon. The teachers pulled a one-day strike a couple of weeks ago as part of their on-going campaign against the government’s new education bill. More strikes are scheduled. Not to mention the doctors and nurses, who are taking continuous, low-grade industrial action for what seems like years. Scientists are marching against cut. Factories are closing down left, right and centre. And, on top of that, your own workplace is this very week entering into negotiations with the union to lay off almost 15% of the workforce and there’s talk of strikes among you and your workmates.

Unemployment in Spain is up at around 27%. We have 50% youth unemployment. Wages are being pushed down. People with jobs are just about hanging on in there. Those without are finding themselves ever more reliant on their parents or grandparents (God bless la familia española) or charity. There are people asking how much more of this crisis the Spanish can take. How much more austerity can be imposed on the people before something gives? The 15-M movement petered out a long time ago and it doesn’t look like any new grass-roots political movement is out there ready to spring into the void created by José Citizen’s complete disillusionment with the two scandal-ridden and corruption-tainted main political parties (the Partido Popular, in particular seems as pickled in corruption as a banderilla).

So where’s the hope, the good news? It will be a threadbare Christmas and flaccid New Year for many. If the streets are still fouled by rubbish by early 2014, the buses aren’t running and God knows what other services have been withdrawn, where will the people of Madrid draw encouragement from entering into the new year? This for me is a question the powers that be must examine and somehow address if Spain is to get back on its feet anytime soon. My own two cents is that the government must stimulate employment at all costs, embrace a culture of transparency that is severely lacking at all levels of administration at present and reach out to the citizenry by showing that the political elite of Spain are willing to impose the same suffering on themselves and their backers in the corporate and banking worlds as they have been on the man and woman on the street.

November 12, 2013

The Strawberry Tree

The fruit of the strawberry tree, Arbutus unedo.

It’s that time of the year again when each of Madrid‘s innumerable strawberry trees is laden with both flower and fruit. The strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo) is one of my favourites and, as luck would have it, Madrid is madroño central (madroño being the Spanish for both fruit and tree). The city’s coat of arms, dating from the middle ages, features a bear on its hind legs reaching up to pick madroños from a tree and you can find this motif everywhere in the city, from manhole covers to dustbins to signs outside official buildings to taxis. Even the football club, Atlético Madrid, features the bear and strawberry tree.

Madrid’s coat of arms, featuring the bear and strawberry tree.

The strawberry tree is a member of the Ericaceae i.e. the heather family. Its greeny-white, bell-shaped flowers are distinctly heather-like, and just like its cousins, the Arbutus is evergreen. Its fruits are large, rough-skinned and (surprise, surprise) scarlet in a way that brings to mind strawberries. Here in Madrid their consumption is not encouraged as they are said to make one drunk, although this is little more than an old wives’ tale (based on the fruit’s high sugar content [15%] and propensity to ferment on the branch in the warm climes of the Mediterranean). While outside of Spain the fruit is used in jam and liqueur making, eaten fresh the madroño, the flesh of which is apricot-yellow, is somewhat dry-textured and bland. My two little girls go madroño-mad at this time of the year; I reckon they are drawn to the sweetness rather than the insipid flavour.

Flowers, ripe and unripe fruits of the strawberry tree, Arbutus unedo.

Arbutus unedo is principally found in the Mediterranean region. Curiously enough, it is also found in south-western Ireland (famously in the woods around Killarney). The species is one of a select group of plants, fifteen in all, native to Ireland but not to Britain. Taken together, these special Irish natives have come to be known as the Lusitanian or Hiberno-Cantabrian flora, owing to the fact that their nearest relatives are to be found on the Iberian Peninsula. How this flora arrived to the blank canvass that was post-Ice Age Ireland is not well understood, but it is possible that they spread overland along the changing coast of the British Isles as they emerged from under glacier and sea. The plant “highway” to Europe has long vanished, swamped by rising seas, with the land beyond the present southern shores of Ireland disappearing beneath the waves almost 9,000 years ago.

Madrid’s livery on a manhole cover.

In spite of the strawberry tree being one of my personal top trees, my Gaelic ancestors didn’t rate it particularly highly. The ancient Irish series of laws governing the use of trees and ordaining fines for damaging or felling them (to be found in the eight-century legal tract, Bretha Comaithchesa [laws of the neighbourhood]) and which additionally places various species in categories ranging from the airig fedo (nobles of the wood; e.g. oak, hazel, yew, ash) to losa fedo (bushes of the wood; bracken, bog myrtle, broom), puts Arbutus (caithne) into the second-last caste (fodla fedo — lower divisions of the wood). Unromantically enough, the Irish only seemed to use Arbutus for manufacturing charcoal or for making small pieces of decorative inlay, as the wood is a rich reddish brown when polished. In contrast to the yew, holly or oak, there is a distinct dearth of folklore, myths and legends surrounding the strawberry tree; no rituals, no cures, no great cycles with the tree at their centre. Nothing! But I don’t mind; with its twisted red-barked trunk, dark green leaves, clusters of white bell flowers, yellow-ripening and crimson-ripe fruits, the madroño has a rugged, defiant beauty that mirrors that of the city that proudly bears its image.

Atlético Madrid logo (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

November 3, 2013

Moving

Boxing your life away.

I’m in the process of moving house again. Me, the ball and chain, the two young ones and a couple of tons of accumulated junk. Our fourth house in as many years. One international move — Ireland to Spain — and three local ones within the same neighbourhood in Madrid in search of the Perfect Apartment. And all those moves on top of the dozen or so as a single person or as part of a young, childless couple (two changes of country included). I guess you could say I have some experience in the area of relocating. So. Some advice vis à vis the old moving house malarkey; DO NOT DO IT! It’s a living hell! It does not get any easier with age or experience — twenty years later, it’s the same exhausting, back-breaking and hair-greying process as the first day you picked up a cardboard box and packing tape and grimly set about the task of transferring the contents of abode A to abode B.

Ask yourself do you really need to move house. Is a bigger kitchen or living room or a killer view really worth the endless hours of wrapping mugs up in newspaper or wondering whether to “do” the office or the spare room first. Is your new gaff sufficiently expansive/cheap/snazzy/well-placed/well-served/etcetera to justify the month or so of torment and agony either side of D-day (when you hand in the keys of house A and collect those of house B). Because – do not doubt me – torment it is. At this point in time if you offered me the option of a month in solitary confinement or moving house I’d gleefully opt for the former. Tour de France or moving house? Gimme that bike! El Camino barefoot with only a verbally dysenteric Star Trek fanatic as company or moving house? Beam me up Scotty!

Two weeks into house moving as I am right now, the miserable situation in which I find myself has led me to much philosophizing on the human condition. We are, I’ve come to believe, a restless species. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors never stayed in one place too long. They followed herds of animals on their migratory paths, hit the uplands or lowlands depending on the season and whatever fruits or vegetable were available at various times of the year and generally bummed around the great plains and primeval forests as part of a sort of proto-couchsurfing lifestyle (although unlike me, they didn’t have to actually lug a couch from here to yonder). I think modern humans, in spite of how sophisticated and urban we feel ourselves to be, retain much of this wanderlust and maybe we’re hard-wired to succumb that itch to follow those proverbial bison from time to time. Or maybe we’re just stupid or suckers for punishment or addicted to the sound, amplified by a good-quality cardboard box, of that brown tape skeetching out of its roll and sticking itself down.

Or maybe it’s boredom . . . One of my all-time favourite books is Independence Day by Richard Ford. The book, the hero of which is a realtor called Frank Bascome, understandably contains much wisdom about buying and renting properties — and house removals. It is within a section describing Frank’s purchasing of a root beer stall, however, that I find a real insight into what leads human beings to undertake crazy, hare-brained, disruptive and mostly unnecessary schemes like house moving. The root beer stall had originally belonged to retiree, Karl Bermish, who set it up with his lump sum to keep him ticking over post receipt of gold watch. Initially, the stall was a huge success for Karl — until he grew bored with the tried and trusted root beer stand “model”. Elaborate and expensive catering equipment was bought on hire purchase. Side-lines were developed. Root beer and weeners became marginalized, became less and less what the stall was about. Sure, the odd yuppie customer stopped by for a latté and gourmet crepe, but the hardcore root beer clientele drifted away. Karl was running his business into the ground. One night, Frank happens upon the stand, gets talking to Karl and gets the full sob-story about how the banks are breathing down the latter’s neck and that he’s only a few weeks from absolute ruin. Frank takes pity on the older man and decides, there and then, to rescue the stall. He buys into the business as the major partner, puts Karl on the books as an employee and, after a sermon on back to basics, divests the stall of all the bells and whistles that Karl had accumulated as a result of his Frank Bascome-diagnosed boredom. In no time at all the stall is a little gold-mine once again.

So there you have it. Boredom, dissatisfaction, itchy feet — the root of all evil, and possibly why I’m carting cardboard boxes up and down stairs again. At least I didn’t buy a root beer stand!!

October 28, 2013

Me and Manchester

Two books – autobiographies – have come out in the last week that have made me realize how much of an influence the culture of one English city has been on my life. Firstly, we have Morrissey’s long-awaited tome, Autobiography, and then, football manager Alex Ferguson’s My Autobiography. What’s the link? Manchester. Alex Ferguson was Manchester United’s manager from 1986-13 and Morrissey is arguably the city’s greatest laureate and most famous son. I’ve been a Man. U. fan for as long as I can remember (there’s a photo of me decked out in a replica kit as a seven year old to prove this) and the music of the Smiths and (to a lesser extent) Morrissey have been on shuffle in my head since my mid-teens.

Manchester Cathedral from Blackfriars Bridge (Photo credit: Pimlico Badger)

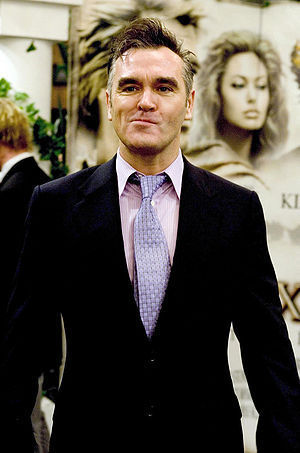

It’s funny that Morrissey’s name has been all over the place lately. When I first became aware of his existence, somewhere in between “The Queen is Dead” and “Strangeways, Here We Come” in the mid-80s, Morrissey was a cult figure – his distinctive quiff only sparking recognition among those in the know. It seems, however, that over the years, in spite of his almost willful obtuseness and his occupying of a distinctly non-commercial niche within popular music, Morrissey’s fame has grown to the extent that his bushy eyebrows and sour puss are as familiar to your (or my own!) mother as Perry Como’s cardigans or Julio Iglesias’ dazzlingly white choppers. Let it be noted, though, that Morrissey is not Manchester’s only celebrated musical export, nor the only Mancunian muso to significantly influence the course of my life. For some reason, possibly to do with its status along with Liverpool and Glasgow as one of the main British receiving points for massive numbers of Irish immigrants from the mid-nineteenth century up until the 1960s, Manchester has always been a musical melting pot, a hotbed of folk and, later, popular music. Since as far back as I care to recall, bands from that city have been high up the list on my personal hit parade.

Morrissey at the premiere of the Alexander film in Dublin Ireland. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

After a visit by the Sex Pistols to the city’s Lesser Free Trade Hall on June 4, 1976 lit the fuse, Manchester exploded into a frenzy of punk and post-punk musical activity, out of which emerged bands like the Buzzcocks, the Fall, Cabaret Voltaire, Magazine and Joy Division. Each of these has been hugely influential on a global scale, with the Fall and Joy Division single-handedly fathering new genres within pop-rock. The group that emerged from Joy Division following Ian Curtis’ suicide — New Order — changed the face of rock ‘n’ roll forever by splicing electronica into the mix. It was into this post-”Blue Monday” landscape that the Smiths nonchalantly wandered with their jangly guitars, classic-songwriting-with-a-bitter-twist and Mr. Stephen Morrissey’s mordant lyrics. After the stellar rise and acrimonious (and subsequently litigious) split-up of the Smiths in 1987 came the “Madchester” scene – a monster, E-fuelled party out of which came stumbling some of the late 80s/early 90s (and mine too!) most acclaimed bands; The Happy Mondays, the Stone Roses and the Charlatans, to name a few. Into the 90s and beyond, the city continued to provide the world (and me) with pioneering groups that pushed at the boundaries of pop (Badly Drawn Boy, the Chemical Brothers, Doves, the Ting Tings) as well as those that achieved massive worldwide success based on well-established formulae (Oasis, Take That, Elbow).

The Smiths in 1985. Left to right: Andy Rourke, Morrissey, Johnny Marr, Mike Joyce. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In spite of this stiff competition, the Smiths are incontestably the quintessential Manchester band. There is no other group that is so identified with the city. They are Manchester’s Beatles. In terms of the lyrical content of their songs (“belligerent ghouls run Manchester schools”, “Rusholme Ruffians”, “and in the darkened underpass, I thought ‘Oh, God, my chance has come at last’”), their use of images and place names from the city (e.g. calling their final album “Strangeways, Here We Come”, being photographed in front of Salford Lads Club for the sleeve of “The Queen is Dead”) and the whole Manchester “vibe” of the band, they firmly declare themselves to be of Manchester.

Manchester United (Photo credit: Donncha Carroll)

As if it wasn’t enough for Manchester to play the role of some kind of world-renowned rock ‘n’ roll nursery for the Next Big Thing, the city has been one of England’s leading footballing lights for a century or more. Manchester’s two top-flight teams — United and City (the less said about the latter, the better!) — are each as significant a player in the history of English and European football as e.g. Joy Division would be in the history of post-punk music. Manchester United enjoyed its most successful period with Alex Ferguson at the helm. Surpassing the achievements of Matt Busby and his teams bedecked with great players like Best, Charlton and Law, Ferguson reaped in the trophies with a form of swashbuckling football that somehow echoed the audacity of the city’s musical mavericks. The names of Ferguson’s players from the late 80′s to mid 90′s are inseparable from my memories of growing up: Robson, Strachan, McClaire, Giggs, Hughes, Keane.

Alex Ferguson, manager of Manchester United F.C. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

His controversial comments about Roy Keane (towards the end of his stint at Old Trafford Keane is depicted as some kind of grouchy control-freak whose humour dictated the entire team’s mood on the training pitch and in the dressing room) dominated reviews last week of Ferguson’s My Autobiography. And here’s my clever link between Morrissey and Ferguson: the singer’s 1997 “Roy’s Keen” — an obvious pun on the great midfield general’s name. The song recalls for me driving to the Cork village of Rock Chapel for a funeral one evening in late April 1999. Tom Dunne (a dyed-in-the-wool Man. U. fan) was on the radio, warming up his listenership for the Juventus match to take place that evening. As we arrived to the village, he gave “Roy’s Keen” a spin. We trooped out of the car, firstly to the removal and then to the village pub, where mourners had more than half an eye on the action from Turin. The game finished up 2—3 – one of United most famous victories – which set them up for winning the Champions’ League a few weeks later. The hero of that night in Turin? Roy Keane.

Roy’s keen, Roy’s keen

We’ve never seen a

Keener window-cleaner

Roy Keane (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

October 20, 2013

Excerpt from The Grotto: politician Pat Landy is introduced to readers

Later that night in a townland called Gortaliscaw, about twenty miles to the east of Loughermore, a man was in an agitated state. His name was Pat Landy and he had been Cork North Central’s Teachta Dála – TD or parliamentary representative – for almost thirty years and, up until the last European election, an MEP for Munster. He had looked forward to an easy, distinguished retirement of sitting on state boards, addressing keynote speeches to summer schools and helping his politician daughter, Audrey, rise up through the ranks of the party, so that one day she would get to be a minister like her father. His plans, however, had come unstuck of late; since the publication of the findings of one of Ireland’s long-running tribunals of enquiry into irregularities in the planning process, he had fallen into disgrace, having been strongly implicated in the receipt of monies in exchange for political influence in general, and the rezoning of certain tracts of agricultural land in County Dublin in particular. His daughter was now the black sheep of the party and had lost her parliamentary seat in the recent election, having been shown to have undeclared interests in a frozen foods distribution company that had won substantially more than its fair share of state contracts. Both he and his daughter had been found guilty of tax evasion and the intimate details of their financial affairs had been trawled through in each of the nation’s major newspapers. The reputation and standing of the Landy political dynasty, which stretched back to Pat’s grandfather, who had been a hero in the War of Independence and one of the leading lights of the party up until the 1950s, was now in tatters, and it seemed as if the Landys’ involvement in Irish politics would end with Audrey’s expulsion from the party at the next general meeting, to be held after Christmas.

“Fuck them,” roared Pat Landy. “Fuck those fucking begrudgers.”

He gulped down what remained of his whiskey and banged the glass heavily onto the coffee table. He looked again at the newspaper on his lap, blinking and squinting in an effort to focus on the headline and read it again for perhaps the hundredth time, this time out loud.

“Landy may have to sell home to meet tax bill.” He spat the words across the room.

He stared at the photo of the journalist who had written the piece, a woman in her mid-thirties with long, blond tresses, and shouted: “Cunt – my grandfather would have had you shot, you skinny, hoor’s git of a cunt.” In the centre of the page was an aerial photo of the sprawling mansion in question with arrows leading from text boxes to various features of the house deemed worthy of mention, such as the stables, the swimming pool and the helicopter pad. Flinging the paper across the room towards the fireplace and shouting ‘cunt’ again, he stood up, wobbled, fell back into the sofa and stood up unsteadily again.

“My grandfather would have burnt you out, you Proddy bitch!” he shouted and staggered out of the room into the house’s considerable hallway.

“I’ll show the fuckers! Ye can all stare up at my house now, fucking begrudging bastards!”

With a lurching, meandering walk, he made his way to the control panel for the house’s alarm and CCTV system which was recessed into a nook under the broad, winding staircase. He flicked a switch and suddenly the hallway was bathed in a brilliant white light that streamed in through the mock Georgian door’s fanlight and wide side panels. Pat Landy had turned on the floodlights and his house was now one of the most brightly illuminated structures in County Cork, visible from miles around and either a point of reference in the locality on a dark night or an eyesore spilling light pollution into the night sky, depending on one’s point of view. The floodlighting system, like many other components of the house, had been installed free of charge, nod-and-a-wink pro-bono, by a contractor who had won, with a little help from Pat, a tender to floodlight a large share of the buildings and monuments under the remit of the Office of Public Works.

Pat walked to the front door, pitching and rolling from wall to wall, yanked it open and roared out into the brightness: “Look up at my house, now, ye fucking peasants! Look up at it, ye begrudging bollixes. At least I had the fucking balls to take what I wanted.”

Pat sniffed, held on to the door frame, cocked his head as if listening, and almost looked surprised that nobody had answered him. He was alone in the house, his wife having gone to their villa in Marbella to escape the shame and embarrassment of the gossip and knowing stares from her neighbours – Pat’s former constituents. Not one to be intimidated or cowed by public ridicule or backbiting, Pat had gone to twelve o’clock mass that morning, as always arriving late and taking his usual seat in the front pew. After mass, he went to his local and had a few pints with some of the old party hacks, who, to his face at least, were as loyal and servile as ever. He came home on his own to an empty house with a sheaf of Sunday newspapers under his arm, intending to spend the afternoon quietly reading each from cover to cover, but, instead, the day had turned into a marathon solo drinking session. He cracked open a bottle of wine to have a glass with his lunch, which consisted of a couple of cheese sandwiches and a banana. Half way through the first sandwich it crossed his mind how far he had fallen since his days of being a minister or an MEP, when he would regularly have power lunches in Strasbourg’s best restaurants with mini-skirted French or Swedish fellow MEPs, some of whom were not averse to his put-on, stage-Irish charm and would invite him to their hotel suites ‘for further bilateral discussions’ as he used to put it, usually to their great hilarity. He grew ever more maudlin as he quaffed glass after glass of the red wine, comparing his current disgraced circumstances with the glory days of his past. He opened a second bottle of wine, fitfully flicked through the newspapers and, having read what they had to say about him, decided it was time to move on to the whiskey. As the bells of the Angelus rang out from the radio, he was stumbling round his large, empty house, cursing the journalists who dared write about him and vowing to get his own back on them somehow.

As Pat clung on to the doorframe, his head hung low and the ground spinning around him, he heard a voice in his head, a voice that had troubled his dreams the night before, and which he had dismissed upon waking as mild hallucinations brought on by the five glasses of brandy he had drunk before going to bed. It was a strong, male voice, a type of voice and accent one only heard in radio documentaries of the 1930s or ’40s – a restrained, commanding, dignified voice.

“You should go and teach them a lesson,” it said.

Pat didn’t answer. His muddled, drunken mind was turning slowly. There was something familiar to Pat about that voice and he delved, mole-like, into the thick fudge of his memories, barely hearing the voice as it spoke again.

“They need to be taught a lesson, me laddie.”

“Me laddie,” whispered Pat and then repeated the phrase perhaps a dozen times.

“We have to stand up to them, me laddie,” insisted the voice again.

Pat released his hold on the doorframe and came crashing down on a potted bay tree just outside the porch. From his prone position on the driveway’s gravel he shouted into the night.

“That’s what my granddaddy called me! That’s what my granddaddy used to call me!”

“That’s right, me laddie,” answered the voice, “and it hurts me to see you this way. You have to fight for the family name, for the Landy name, for Ireland, just like I did.”

“Fight for Ireland,” mumbled Pat, picking himself up and half-sitting on the rim of the bay’s stoneware pot.

“Yes! Strike a blow against Ireland’s enemies. Bring glory to the Landy name again. You know what you have to do.”

“I know – I’ll start with that Proddy bitch. I’ll burn her out!”

“Yes, burn her out. Will you do that for me?”

“I’ll do it for you!”

With that, Pat slid off the pot and ran with a stumbling, lurching gait back inside the house. He rummaged in a drawer in his study for the keys to his Mercedes and, having found them, raced out to the driveway, crashing into a selection of antique chairs and tables on his tumbling journey from study to front door. After fumbling with the remote control to unlock the doors, he fell into the driver’s seat and started the ignition. He released the handbrake, changed from neutral into first gear and stomped heavily on the accelerator. The engine roared and the car leapt forward, wheels spinning on the driveway’s gravel. Before Pat could react, the car had reached the sharp elbow bend that led onto the steep descent from the hill atop which the mansion sat to the public road below. As Pat tugged on the steering wheel half a second too late and pushed the brake into the floor with all his might, the car trundled off the driveway and came to a thumping stop against a fencepost in the ditch that ran alongside it. The airbags activated instantly and Pat’s head was prevented from slamming into the steering wheel by the white softness of the steering column’s oval cushion. In his drunken state, Pat somehow imagined that he managed to make it back to his bed, and, hugging the airbag tightly to himself, he rested his head on it and fell into a deep but unrestful sleep.

October 13, 2013

Top Ten Madrid Smells

When Victoria Beckham came with her husband to Madrid in 2003, she reputedly made a comment along the lines of “Spain smells like onions and garlic”, which did little to endear her to the natives. Walking home from work the other evening, I happened into an invisible but highly substantial cloud of frying onion and garlic aroma (emanating from an open kitchen window a couple of floors above street level) and started thinking about the former Posh Spice’s comments. Madrid does sometimes smell like garlic and onions but it also smells like other things. Here’s my top ten:

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

1. Coffee

Whether wafting in the window from a neighbour’s kitchen early in the morning or spilling onto the street from one of Madrid’s multitude of bars, the aroma of rich and flavoursome coffee is never far away. The Spanish take their coffee very seriously. There’s no cutting corners on quality or the elaborate technique involved in its preparation. Coffee isn’t just a morning thing; excellent coffee can be had anytime, anywhere in Madrid.

2. Cigarettes

When I first set foot in Spain over ten years ago, everybody smoked. Everywhere. In the airport baggage hall. In the taxi. In the supermarket. In the bank. In hospitals. And it was a different kind of tobacco from that to which I was used: black tobacco (tobaco negro), which has a deeper, heavier, more pungent scent. The most famous brand of black tobacco is Ducados ― an iconic Spanish brand in the same way Marlboro would be American. Nowadays, not so many Spaniards smoke and the restrictions on where you can light up are much less lax. You can’t even smoke in bars since 2010. But still, the smell of black tobacco is ever-present and something unmistakably Spanish.

3. Metro

It’s probably true that all cities’ metros (or subways or undergrounds) have their own unique smells. Madrid’s is a fusty, damp odour, something very organic, as if the dampness at the heart of the smell is not groundwater, but ― how shall I put this? ― raw sewage! It’s not a totally unpleasant smell, in the same way the smell of rotting seaweed isn’t quite 100 percent noxious; there are some agreeable undertones. Ironically enough, the metro smell is stronger above and outside the metro, as one passes a vent, than down below, which probably says more about modern ventilation techniques than anything else.

4. Wheat

This is a summer smell. On searing-hot Summer days, when temperatures are up in the mid-thirties and there isn’t a sinner in the city ,the smell of the countryside invades the glass jungle. Much of Madrid is surrounded by wheat fields and it is this papery, dry smell that hangs in the air throughout June, July and August.

5. Old-man cologne

Spanish older gentlemen are fastidious about their appearance and meticulous in their grooming. Highly laudable and indeed welcome, but they do tend to go a bit overboard on the aftershave, to the extent that at a certain hour of the morning, when they sally forth to buy the newspaper and bread, the smell of old-man cologne dominates elevators, stairwells, corridors and indeed certain sections of streets close to bread shops and press stands. Brands favoured by these old men are Varón Dandy, Agua Brava and Aqua Velva. These are available to buy in litre bottles, which obviously encourages their liberal application.

6. Rain

The smell of rain isn’t very common in Madrid, but maybe 20-30 days a year, the city clouds over and the whiff of rain is on the breeze. This sends most Madrileños scurrying for cover, but as an Irishman living in the city, I smile with relish and prepare myself for a little singing ‘n’ shenanigans in the rain.

7. Fallen poplar leaves

A musky, autumnal smell. The poplar (el chopo) is one of the most commonly-planted trees in Madrid. As they begin to lose their leaves in late October, the streets fill with their roughly triangular leaves. Kicking through a wind-blown bank of these raises a rude and vital smell to the nostrils.

8. Onions and garlic

Mrs. Beckham wasn’t telling a lie! The Spanish do love their onions and garlic. (Innumerable dishes are based on the two ingredients.) They do love to fry. At certain times of the day the streets do smell of onions and garlic (along with other foody smells). It’s not an unpleasant mixture. It could be worse. Get over it people!

9. Summer street

It’s August. It’s forty degrees. It hasn’t rained since May. There isn’t a puff of wind. You stick your head out the balcony and you’re hit by a heavy, overpowering smell ― Summer street. A mix of desiccated drain ooze, dirty footpath, oily road, melting tar, traffic pollution, all the aforementioned street smells (tobacco, cooking etcetera), dust, pollen ― you just wish it would rain so that some of the components of the wall of smell could be washed away.

10. Churros

I mentioned these confections in a previous post. Most neighbourhoods have churrerías. The aroma of frying churros and bubbling hot chocolate is, along with roast chestnuts, one of the principal smells of the Madrid winter street.

October 6, 2013

Party Time in the Barrio del Pilar

The twelfth of October is an important date in Spain — a national holiday in honour of la Virgen del Pilar (The Virgin of the Pillar). Each city, town and village has its own distinctive statue of the Virgin Mary to which are ascribed miraculous properties and which are in turn venerated according to local custom and tradition. Madrid has a number of Virgins — la Virgen del Almudena, la Virgen de Atocha — as do other large cities such as Seville or Barcelona, but it is Zaragoza’s Virgin, la Virgen del Pilar, that has gained national and international prominence (she is the Patron Saint of “Hispanidad” — Hispanicity). The Virgin of the Pillar’s story is quite intriguing and has its origins in the very beginnings of Christianity. (If you want a less formal, bar-room discussion of the Virgin, see my book, the Grotto!)

Francisco de Goya, The Apostle, Saint James, and his disciples worshiping the Virgin of the Pillar, 1775-1780, 107 x 80 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In the year 40 AD the Virgin Mary (as a mortal, pre-Assumption) appeared to St. James in the Aragonese city of Zaragoza (then Caesaraugusta, an important outpost of Roman rule in Hispania). As evidence of her apparition, she left behind a column of jasper — the Pillar (el Pilar). Whatever about the truth of its origins, the Pillar (1.7 m high and 24 cm in diameter) seems to have been an object of devotion from the very earliest Christian times, forming the centerpiece of a series of ever more elaborate chapels and churches until the current massive cathedral was completed in the seventeenth century (although bits and bobs were added to it well into the twentieth century). Legend states the Pillar has never been moved from its original spot. The late gothic statue that currently sits atop the Pillar dates from 1435 and is attributed to one Juan de la Huerta. The Virgin is crowed and wears a long tunic and cloak and rests in a specially-constructed chapel in the cathedral. On the second, twelfth and twentieth of each month the cloak is raised, allowing devotees to see the full Pillar. On the twelfth of October, the Virgin is the protagonist in a number of ceremonies and traditions, including the Offering of Flowers, a pontifical mass, the Offering of Fruits and the unique and celebrated Procession of the Glass Rosary, which winds its way through Zaragoza at night.

View from the big wheel, Fiestas del Barrio del Pilar, 2013.

In Madrid, I happen to live in a neighbourhood called the “Barrio del Pilar” — the neighbourhood of the Pillar — dedicated to the Virgen del Pilar. From the first weekend of October until the weekend after the twelfth it’s party time here! One long street is closed off and becomes taken over by carnies, hawkers and food stalls of every description.

Fiestas del Barrio del Pilar, 2013.

We have a big wheel, bumper cars and all sorts of other amusements. There’s the smell of fried chorizo and chistorra floating on the breeze. Popcorn, candyfloss, roast chestnuts, beer, sangria and patatas bravas are only a few steps to the nearest stall away. From early evening until late at night crowds flock to the fiestas, which culminate in a series of concerts and a fireworks display.

Mojito Stall, Barrio del Pilar.

Those of a religious persuasion can take part in the events centred around the many churches in the neighbourhood and, in the chill of the October nightfall, it really feels like the fiestas are the last hurray of the summer. From here on in the weather will get cooler, the leaves start to turn and we’ll see an end to the long, balmy evenings we’ve enjoyed heretofore. So we’ll cherish the party while it lasts and save a thought for the Pillar of jasper in Zaragoza, in whose honour the whole shebang is.

Waiting for the party to start.

September 29, 2013

Figs

The fig harvest comes around twice a year in Castile. The first crop (using energy reserves built up the previous year) comes in late May, early June. In Spanish these first fruits are called brevas, while the second fruit is an higo. In English, the fruit is always referred to as a fig, whether it comes from the first, second, third or fourth wave of fruits (believe or not some varieties of fig trees grown under the right conditions can fruit up to four times in a year), although the first harvest is called the “breba crop”.

Rip (yellow-green) and unripe figs.

I have never come across a fig tree in fruit in Ireland, it being a species that likes a dry soil, heat and sunshine. Of course like every Irish child I was practically raised on Jacob’s Fig Rolls, but I didn’t see a fresh fig until well into my twenties. In contrast, my daughters are seasoned fig pickers (and eaters). Fig trees are an easy climb and the ripe fruit (softer and more yellow than the unripe fruit) comes away with the slightest of tugs.

There’s room in this tree for two!

The only thing to watch out for when picking figs is the sap from the branches and leaves: it is highly irritant. The wearing of a long-sleeved shirt and gloves is recommended. I never want a repeat of the burning, itching sensation I experienced during my first session up a fig tree, when I ignorantly ventured into its branches in a T-shirt.

Come to Daddy!

A fair-sized, twenty-year-old tree would probably yield a couple of pounds of fruit per day over the month of September. Unless you have a ready-made army of figaholics (or have figured out how to make your own fig rolls) most of these will go towards jam-making. There are people who swear by deep-freezing their surplus figs, but I think it is a more efficient use of space and energy to get those higos into jars ASAP! Figs can also be dried. A traditional Castilian delicacy based on dried figs stuffed with nuts is called turrón de pobre.

It puts the fruit in the basket!