Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 29

September 2, 2021

(11/12) “My thoughts grew very dark. It felt like I was wearing...

(11/12) “My thoughts grew very dark. It felt like I was wearing new clothes, and I wanted to remove the clothes. But how could I remove my skin? And if I did, what would be left? I tried to push my feelings aside. I tried to switch off my emotions. But this time it wasn’t working. I even stopped riding the subway because I didn’t want to stand near the tracks. Every morning I would take a few moments to collect myself, before I called my daughter. I never wanted her to see my sadness. For the longest time I had been the one comforting her. But somewhere it switched. And she was the one keeping me going. I would force myself to smile, and laugh at her silly jokes. Every time I tried to correct her, if I scolded her for being stubborn or disobedient, she would tease me. ‘Everyone says I’m just like you,’ she’d say. It would always make me laugh. But this isn’t what I wanted for us. When I promised to give her a great life, all those years ago, this isn’t what I wanted. To be laughing on the phone together. From 5,000 miles away. She’s getting older so quickly. She doesn’t read the same books. I’ll send her small books, like we used to read together. But she doesn’t want them anymore. She wants cookbooks, or traveling books. Sometimes I will send her clothes, and she’ll tell me: ‘Daddy, this doesn’t fit anymore.’ Or I’ll send her calendars with her favorite cartoon, but she’ll say: ‘Daddy, I don’t watch that anymore.’ And she’s tired of taking photos on her grandmother’s phone. She wants a professional camera now. It’s like: where has she gone to? The Ella I left in Ghana is not the Ella I know now. There are times when she doesn’t feel like praying with me. And there are things she doesn’t want to speak about anymore. She still has a journal, and she still writes in it every day. But she never wants to show me what she’s written anymore. Now her journal has a key. Last week we were making lists for her upcoming birthday. I’ve always been the one who plans her birthday. We choose the cake together, and the games, and the theme. And here we were doing it again, only this time on the phone. And it hit me. It hit me so hard. I’m going to miss another birthday.”

(10/12) “Growing up in Ghana, I’d never once had to think about...

(10/12) “Growing up in Ghana, I’d never once had to think about my skin color. I saw myself as African. I saw myself as Ghanaian. I saw myself as Asante. But never black. Because all of us were black. And to become sensitive to your skin, for the first time, at the age of thirty, it messed me up. One morning I was greeting my fellow students in the lounge, when one of them said the strangest thing: ‘I’m too white to shake your hand,’ he said. I was so confused. Another student rushed to defend me. ‘That was a racist comment,’ he said. Others dismissed it as a bad joke. But the comment stuck inside me. I’d been rejected so many times in my life: for being too poor, for not being good enough, but never this. On that day my soul began to change. I thought: ‘Maybe my kindness is the problem. Maybe if I’m less friendly, and keep to myself, I will never encounter this again.’ I’d spend hours walking around the city alone with my camera. When I wasn’t doing that, I was collecting photography books. I went to every bookstore in the city. It was something positive to focus on. I filled up an entire bookshelf in my apartment. Then another. My goal was to gather enough books to open a photo library in Ghana. It gave me comfort knowing that no matter what happened to me, my time here would be useful to someone. After I spoke to my daughter each morning, I would call my mother. We’d read the Bible together. She’d pray over me. We called it ‘Morning Revival.’ Sometimes I’d be calling her to complain, and she’d be singing, rejoicing. It made my problems seem so silly. My mother grew up in a small town. She had no clue about life in New York. ‘You are an Apostle,’ she would tell me. ‘You have so much more to write.’ One morning after we spoke I jumped on the subway to go to school. Maybe I looked a little sad that day. I’ve wondered so many times, if I looked sad. Or if my clothes were dirty. I’d bought my coat at a discount store. But it was a Columbia coat, and it wasn’t dirty. I’m sure of it. I’ve thought about it so many times. Because when I got up to leave the train, a woman tapped me on the shoulder. She handed me a dollar. ‘Buy yourself some food,’ she said.”

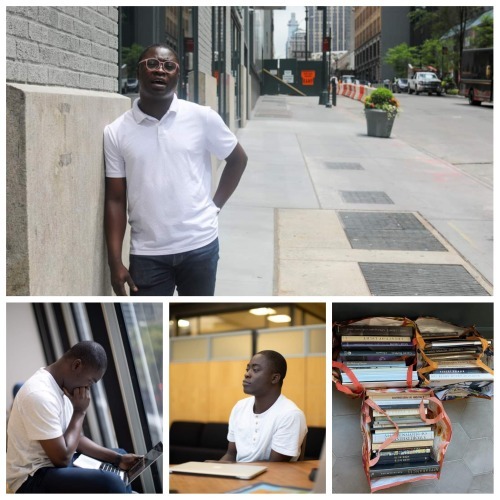

(9/12) “Every day after class I went to the main branch of the...

(9/12) “Every day after class I went to the main branch of the New York Public Library. It was my favorite place in the city. I couldn’t believe how big it was. This place had every book in the world. In Ghana I hadn’t been able to find a single photography book, but here there were entire books with nothing but photos from Ghana. When I was learning to become a photographer, these books could have helped me so much. But the whole time they were here, 3000 miles away, sitting on a shelf. It didn’t make sense to me. Each week I got a small stipend from Humans of New York. Half I sent home. With the remainder I went to second-hand bookstores around the city, buying their African photography books. I planned to bring them back home with me so that other young photographers would have something to study. The time difference with Ghana was five hours. So every morning the first thing I did was call my daughter. I’d speak to her for an hour on her lunchbreak. At first she was in denial about how long I’d be gone. It just seemed like another of Daddy’s trips to her. She loved looking at pictures of all the new places I’d been. But after a few weeks the questions began. Always she was asking: ‘When are you coming?’ ‘When are you coming?’ I did my best to stay on top of everything, even though I was far away. I’d wake up at 3 AM to help her study for tests, or complete her own projects. I knew every assignment and test score. I knew the friends she was making. I even knew the cartoons she was watching. I tried my best to be there, but still, I wasn’t there. The guilt began to weigh on me. But I did what I always do. I switched off my emotions. I pushed my mental health aside, and reminded myself of the opportunity I was being given. But there was one other thing. Something I wasn’t prepared for. Every morning I stopped into the same bodega to buy breakfast. And I kept noticing that the owner was following me through the aisles. Sometimes this would happen in Ghana, but they’d always ask if you needed help. And this woman never asked if I needed help. So one morning I asked her: ‘Is there a problem?’ ‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘Black people have been stealing from me.’”

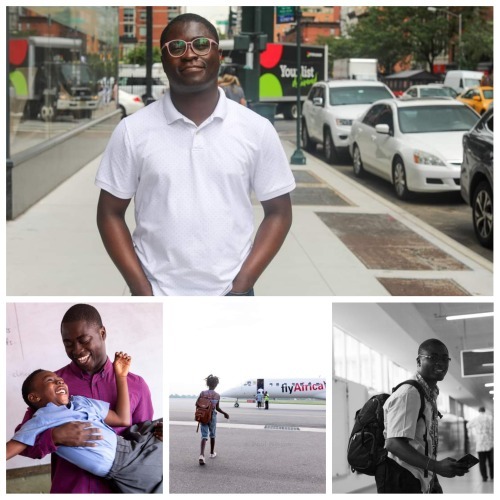

(8/12) “When I landed in New York I was full of joy. I spent the...

(8/12) “When I landed in New York I was full of joy. I spent the first few days exploring the city. I saw places that I’d only seen in photographs: Times Square, Central Park, The Empire State Building. During orientation I met other students from all over the world. There were so many subjects to choose from, and I signed up for the maximum number of classes. I knew what I was sacrificing to be here. And I was determined to take advantage of every resource. Many of our lecturers had worked at famous magazines or newspapers. I couldn’t wait to meet them. One instructor told us to bring along our best photos to her workshop, because she’d be providing a critique. This was a very successful photo editor. She’d had a very long career, and published several books. I’d never had an opportunity like this in Ghana, so I was excited to get her feedback. But I was very nervous too. When we arrived at the workshop she told us to lay our selections on the table. She went around the room, one-by-one, and began to critique each student’s photography. Most of her comments were constructive. She’d say: ‘This isn’t quite working,’ or ‘Try moving this here.’ One student had taken photos of a snowfall in Massachusetts. She especially liked those. It looked like snow to me, but she called them ‘dreamlike,’ and ‘surreal.’ Finally she came to my photos. There were about forty of them. I thought they represented a wide range of my work. But she took one glance and waved them away with her hand. ‘I don’t want to see pictures from Africa,’ she said. ‘I’ve been looking at them my entire career. It’s too much poverty and propaganda.’ At first I was too embarrassed to speak, but then I grew angry. Were all African stories the same to her? Did they not have value? Because those were the stories I wanted to tell. One of my friends secretly snapped a photo of me, and you can see the anger in my face. When our workshop was finished, the lecturer showed us a copy of her new book. It was full of pictures of her own life, and her own family. She was very proud of it. The price was $50, which was all the money I had. But I bought it anyway. Because I never wanted to forget what she said to me.”

(7/12) “My father is not an emotional man. But when I gave him...

(7/12) “My father is not an emotional man. But when I gave him the news, I could see the pride in his face. He was proud of the scholarship. Proud of everything I’d overcome. I was proud too. Oh boy, the things I was thinking! I felt like an important person. I was going to America to study at a famous school. ‘When I come back to Ghana,’ I thought. ‘Everyone in the country will know me.’ My mother was so excited that she burst into one of her hymns. But afterwards she prayed with me for hours. Because she knew how worried I was about my daughter. The program would last for a full year. I was scared for Ella’s wellbeing. Scared for our relationship. She would be with her mother and grandparents, but I was the one who helped with her homework. I was the one who picked her up from school most days. She loved when I picked her up, because her classmates would scream: ‘Your dad is here! Your father is here!’ But now I would be arranging a driver, from the other side of the world. During my final days in Ghana, I stopped everything to be with her. We unpacked a lot of things between us. She asked me questions that she’d never asked before: mainly about her mother, and the reasons we weren’t together. I tried to cover in a certain way. I focused on my own mistakes. I explained that we were two different people, and we didn’t understand each other. Eventually she asked why she couldn’t come with me to America. I told her that it wasn’t possible, but that I was taking the trip for both of us. And when I came back home, I’d be a proper photographer. I’d be making real money, and we’d have time to be together. We’d have a proper home. She could have a room of her very own. We could get a dog. And we could travel. That was always the biggest thing between us—travel. Ella wanted so badly to travel. Before I left for New York, I bought us two tickets on an airplane. It was just a 45-minute flight, from my hometown to the capital. But it was enough for her to see the skies. She was so happy. She was taking photos of the clouds, and taking photos of me. And it gave me some peace, because I’d been making promises her entire life. At least I’d been able to fulfill this one.”

(6/12) “It was time for me to face the truth: there wasn’t...

(6/12) “It was time for me to face the truth: there wasn’t a path for this kind of thing in Ghana. Photojournalism was not a way to feed my daughter. I stopped looking for stories to tell. I went back to weddings and events, and took any job I was offered. Later that year I was hired to photograph a program at the University of Ghana. The work was barely paid, so I remember not wanting to be there. But shortly after I arrived on campus, I noticed a tall foreigner with a camera. He seemed to be interviewing one of the students. I whispered to my friend: ‘I know that person. That is Humans of New York.’ My friend didn’t believe me. But I was sure, because I’d seen him interviewed on one of my online tutorials. I did what I always do when I see another photographer, I approached him to ask for advice: ‘How did you start? ‘How did you do it?’ But soon after we began speaking, he asked if he could interview me for his own project. To be honest I wasn’t very familiar with his work. So I wasn’t prepared. He began asking very personal questions, like: ‘What is your greatest fear?’ And ‘What’s your greatest struggle?’ I was caught off guard. Maybe because I’m so hard working. Maybe because I switch off my emotions, but nobody had ever asked me about my problems before. I told him about my daughter, and the promise I’d made so many years ago: to give her a great life. I talked about my journey with photography. I told him that I hadn’t had much luck so far, but that I’d recently gotten a half-scholarship to the International Center of Photography. Except I couldn’t afford to go. That’s when he said: ‘Show me your work.’ It was the same words that I’d heard from the woman at the gate, but this time I had something to show. I took my laptop out of my bag, and pulled up my photos from Kenya. He looked at them very closely, for a long time. He seemed very interested. ‘Would your scholarship still be valid? he asked. ‘If you were to find the money?’ It seemed to me like maybe something was going to happen. We exchanged phone numbers. But I wasn’t hoping for much, because I’d been disappointed so many times before. But then again, if something was to happen, Amen.”

(5/12) “I’d been rejected at the gate because I didn’t have a...

(5/12) “I’d been rejected at the gate because I didn’t have a ‘body of work,’ so after that day those words became very important to me. I spent all my time in the internet café, researching stories that belonged in a ‘body of work.’ I discovered a blog post about a community of women in Kenya, who had built a village to escape their abusive husbands. It was a village with no men. This was a profound idea to me, especially as an African man. It felt like a story that needed to be told. But the airfare alone would cost $600, which was all the money I had. It was money I’d been saving for Ella. She begged to come with me. She knew there were lions in Kenya. She really wanted to see a lion. And her school was near an airport, so she’d always wanted to fly on a plane. But all I could do was promise that we’d go back together one day. The women welcomed me warmly when I arrived. I spent three days living among them, and during this time I grew to respect them so much. Men had attacked their village many times, but somehow they persevered. They shared all their resources. They did all their own farming. While I was there they were building a school for their children. I tried to photograph them from below, like they were statues, or monuments. And when it was time to leave I felt so ashamed that I had nothing to offer them. I could only promise that I’d share their story with the world. When I got home I sent the photos to every publication: every newspaper, every magazine, every website. But I didn’t receive a single response. It was shameful. I felt so guilty for taking their time. I used the photos to create a GoFundMe, and was able to send them $70. It wasn’t much help. But at least I could show them my gratitude. My only remaining hope was to use the photos to apply for overseas programs. I filled out so many applications, and only one acceptance came back, from the International Center of Photography in New York. They even offered a half-scholarship. For the first few minutes I was so excited, but then reality set in. Even with the scholarship, the remaining tuition was $20,000, it might as well have been a million.”

(4/12) “The online tutorials made photojournalism sound easy:...

(4/12) “The online tutorials made photojournalism sound easy: ‘Quit your job, find the best story, get published.’ But this advice was for Westerners. Nobody quits their job in Ghana. And even if you did, there’s no place to publish your photos. I’d see pictures from Africa, and stories from Africa. But everything was done by foreign journalists. I tried photographing local festivals. I even snuck into a slaughterhouse to document the conditions. But when I pitched these stories to publications, nobody even wrote me back. Every time I read an article, I would email the photographer. I’d ask them: ‘How did you start? How did you do it?’ But I received very few responses. After several months I grew discouraged. I was desperate for some sort of community. Then one morning I saw a Facebook post about a meeting for photographers in the capital city of Accra. I couldn’t believe it: a group of people, just like me. And they were Ghanaians. My own countrymen. I could ask them, face-to-face: ‘How is this possible? In our society?’ The night before the meeting I was too excited to sleep. I woke up at dawn and took the first bus to the capital city. When I arrived at the location there was a woman stationed at the gate. She saw the budget camera hanging from my neck, and she stopped me. ‘This is a meeting for professional photographers,’ she said. ‘Show me your body of work.’ All I had were the pictures on my memory card. They were pictures of my life, and pictures of my daughter. ‘That is not a body of work,’ she told me. Inside I could see the meeting was about to start. The photographers were taking their seats. ‘Fine,’ I told her. ‘I’m not a photographer. But I’m here to learn. So that I can become a qualified person.’ But she wouldn’t listen. She closed the gate. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘This is a meeting for photographers.’ On the bus ride home I called my mother. She’d been so excited about the meeting. She’d been praying and praying about it. But when she answered the phone I could not speak. From my silence she could tell that I was holding onto my tears. ‘This won’t be the end for you,’ she said. ‘You are an Apostle. You have so much more to write.’”

(3/12) “I sold all my possessions. I even let go of my...

(3/12) “I sold all my possessions. I even let go of my apartment. But still it was not enough for a camera. So I turned to my mother for help. She sold second-hand clothes for a living. She knew nothing about photography. But when I told her a camera would help me be a father, she trusted me. She took out a loan and we purchased a budget model. It wasn’t professional quality. But I was so proud of it. I wore it around my neck like a shoeshine boy, so people would say: ‘Look! Here comes a photographer!’ I was determined to learn everything about photography, but it wasn’t really a thing in Ghana. There were no fellowships, or workshops, or grants. It was hard to find a single photography book. I spent hours in the internet café, watching online tutorials from overseas. I committed to taking 200 photos per day. It became like a form of therapy for me. There was so much in my life I couldn’t talk about, but this was a way to express myself. It took me away from all my thinking. My mother sat for me while I practiced my portraits. But my favorite subject was Ella. I documented all the times we spent together, every time we went to the park, or went on a walk. She loved posing for photos. And for the first time I noticed that she was beginning to look like me. But it was more than just looks. There was so much of me in her. She couldn’t sit still. She’d ask so many questions. I bought her a journal and she filled up the pages with thoughts. Thoughts I never knew she had. It was beautiful to see, but it was scary too. Because she was getting more complex. And so were her needs. Ella told me that her dream was also to become a photographer, so that she could photograph animals. Some nights we’d flip through old National Geographic magazines, looking at animals. And whenever we found an interesting article, I’d google the photographer. That’s how I first learned about the job of ‘photojournalist.’ It seemed like the perfect life: going everywhere, travelling, telling important stories. Stories that could educate people, and change minds. As a young boy I’d dreamed of making a difference in the world. But then I became a father. Maybe this was a chance to do both.”

September 1, 2021

“I was working as a school secretary. I’d just turned 40. My...

“I was working as a school secretary. I’d just turned 40. My kids were finally a bit older, so I decided it was time. College was unfinished business for me. I’d gotten pregnant when I was seventeen. My mother kicked me out of the house, and I was forced to drop out of school. My entire life I’d wanted to go back and check that box. At first I was just planning to get my undergrad degree, but halfway through I thought: ‘Wait a minute, I’m going to be a school counselor.’ My biggest motivation was all those years I’d spent as a young mother: trying to take care of three babies, while still growing up myself. My mother had disowned me. My marriage wasn’t the healthiest. There was nobody to talk to. Everyone in my life had either broken my trust, or left me without support. Imagine living your life until the age of thirty, alone and scared. Scared was the big one. I hadn’t really processed what had happened to me as a child. I just knew that I was scared of life. I got nervous whenever I was alone in a room with a man I didn’t know. And there was nobody to make me feel safe. And not having anyone to make you feel safe, is hard. I ended up becoming a counselor at the same school where I worked as a secretary. It’s been almost ten years now. I love helping kids manage their emotions. I love seeing their family dynamics work better. But most of all I love being someone they can trust. It makes you feel proud, when something about you makes a child comfortable enough to share their pain. Something about you makes them feel safe. It’s not an easy thing to obtain. But when there’s trust, there’s no barrier anymore, it just makes the air a lot easier to breathe in. The school feels more like an extended family now: students and parents seeking me out, emailing me, thanking me. The gratitude piece still kicks my butt sometimes. Because it’s easy to not feel deserving. Because of all the mistakes I’ve made. Because of what happened to me when I was young. But when a student turns around, 5 or 6 years later, and says: ‘My life is so much better because of you.’ It almost makes sense. It’s like: ‘It happened, Rosa. But look what you’re doing now.’”

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 768 followers