Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 30

September 1, 2021

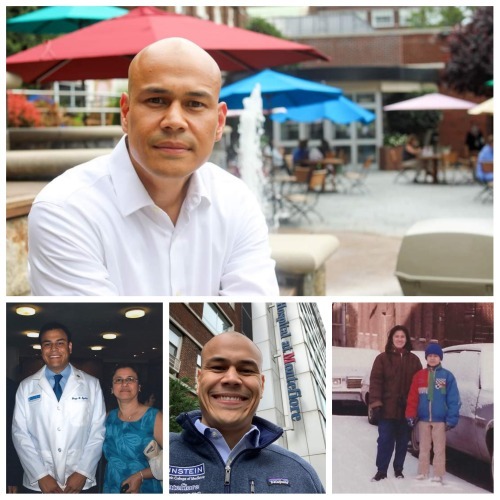

(2/2) “I got saved by my baseball coach. His father was a judge,...

(2/2) “I got saved by my baseball coach. His father was a judge, so he connected me to a powerful law firm. And they took my case pro bono. I was allowed to stay in the country, but I couldn’t qualify for student loans or financial aid. The only college that offered me a scholarship was Swarthmore. I flourished there: varsity sports, president of my class. I became a citizen while in med school. Initially I pursued pediatrics, but what I enjoyed most was talking to kids and parents. Especially the black and brown ones. So I switched to child psychiatry, and came home to the Bronx. All of our patients here are black and Latino. You can feel the tension ease the moment I walk in the room. They’ve seen nothing but white doctor after white doctor, and finally, someone who looks like them. Who grew up in their neighborhood. Who understands the struggle. They don’t have to worry about sounding uneducated, or dumb, or anything negative. Cause I know that’s just how we talk in the Bronx. My patients trust me. And I know how important that is, because I’m also seeing a therapist. I’m also trying to get comfortable in this world where no one looks like me. Sometimes I’ll be waiting for the parking attendant and a fellow doctor or nurse will hand me their ticket. Without a word. That’s happened twice or three times. It makes it so hard to not see my colleagues as barriers. They’re the gatekeepers. They’re the ones who approve the applications, and give the interviews. They’ve closed the door in my face so many times. Because my SAT score was too low. Or they thought my reading score was a reflection of my potential. They didn’t know my mom only finished third grade. Or how scared I was sometimes, just going to school. They don’t know that I was beat up on my first day of third grade. They don’t know how that changed me. They don’t know how hard it was for the rest of us. Because all they’ve ever known are the people who look like them, who grew up with them, and who made it here with them. They think it’s normal, that I’m the only one here that looks like me. They don’t see it as a problem. But I do. And our patients do, which is why they light up every time I walk in the room.”

(½) “My mother and I came from Costa Rica when I was...

(½) “My mother and I came from Costa Rica when I was seven. And on the first day of third grade I was jumped because I didn’t speak English. Two kids held my arms, while the third punched me in the stomach. I didn’t know how to say: ‘Why?’ So I kept saying: ‘But what? But what?’ Before then I’d always been a chipper child. I was eager for life. I sang a lot of songs. I spoke joyfully to myself. But by the time I got to junior high I never smiled anymore. My school was in Hunt’s Point so you could see Riker’s from our classroom. My first priority every day was to get home safe. Teachers were getting beat up, lockers were being set on fire. I never raised my hand in class. I was a straight up C student. All day long I wore an expression that said: ‘You don’t know me. So don’t mess with me, or you might get hurt.’ It wasn’t true, of course. I was just scared. When it was time for high school I tried applying to specialty schools, but got rejected by each one. My only option was the ‘zoned’ school next to my housing projects, which meant more of the same for me. Our guidance counselor encouraged me to apply for a sponsorship program for ‘at risk’ kids, and I was assigned to a Catholic school on the Upper West Side. It wasn’t elite or anything. But it was safe. For the first time I felt safe. I was coming from a classroom where I’d get teased or hurt for raising my hand. But now I was in a place where it was praised and encouraged. My old eagerness came back. I started smiling again. Every morning I took an hour-long subway ride. And as soon as we crossed into Manhattan, there’d be this influx of white people wearing expensive clothes. I was determined to be part of that world. That very first year I started making straight A’s. I signed up for every club, every team. I even received the school spirit award. I was getting ready to apply for college when a letter came to our house. My mother couldn’t read English, so she handed it to me. I was too hurt to read the entire thing. But I remember the first line: ‘Your application for permanent residency has been declined because your household income is too low. The next step is voluntary deportation.”

“This place was a big part of their lives as a couple. When Dad...

“This place was a big part of their lives as a couple. When Dad came home from art school, his bus would drop him off in front of the diner. Most of the time Mom would meet him for a meal. And in the ten years since he’s passed away, she’s continued to make the four-block trip. Her mode of transport has shifted over the years: from her legs, to a cane, to a walker. But unless it’s snowing or storming, she’s coming to the diner. Occasionally she’ll ask me to come with her. I tried to fight her in the beginning. I told her: ‘Mom, there are so many choices in New York. Why does it always have to be the diner?’ But she always insisted. So eventually I stopped fighting, and started paying attention. Mom’s always greeted by name when she walks in the door. And she almost always orders the same thing: a special grilled cheese sandwich with half-avocado and half-tomato. The entire staff knows her order. They call it the ‘Sarita Sandwich.’ There’s no frills or pretension here. She can just order a decaf and sit for an hour. She can get a table at 11, or 3, or 5. Everyone says ‘hello’, other customers, the waiter, even the owner. It’s the center of her social life. Mom’s a stoic, so she’d never complain. But she’s 92 now. Most of her friends have passed away. And it could be so easy for life to get narrow: waiting for people to visit, watching TV, reading the paper. She’s always been such an independent woman. She came from the Belgian Congo when she was eighteen. She’s made bold decisions her entire life. But when you’re 92, and you have arthritic knees, there are fewer decisions you can make for yourself. But every day she makes the decision to come to Cafe Eighty Two. And when she walks through that door, she’s greeted by name. With a smile. She’s been battling a tremor recently. It’s become difficult to hold utensils. Not to mention a full cup of coffee. But they’ve made it easy for her; they now bring her coffee 3/4th full. With a side of ice on the side, so she can cool it down, and drink with a straw. She still always gets the same Sarita Sandwich. Only now when they bring it out, it’s already cut into tiny little pieces, so she can eat it with one hand.”

August 28, 2021

“Our community was hit first. Asian restaurants were empty long...

“Our community was hit first. Asian restaurants were empty long before other restaurants. Even on the subway I could sense that racism was on the rise. On television one night there was a story about an elderly man who was collecting aluminum cans, just to survive. He was robbed and taunted. His bags were broken. His cans were strewn all over the street. And he didn’t speak English, so he couldn’t even ask for help. It broke me. Because in his face I could see the faces of all our grandparents. In our culture there is a tradition of: ‘Never speak out. Never ask for help.’ If our elders were suffering, would they even let us know? I decided to call a service organization focusing on Asian elderly, and I asked: ‘How many meals do you need?’ They replied: ‘As many as you can cook.’ We started preparing 200 meals per week in our little 300 square foot apartment. Moonlynn cooks beautifully and efficiently, so she lovingly banned me from the kitchen. But I still wanted to help in some way. So I found a black sharpie, and began to write on the plastic containers. Traditionally our elders are very reserved with their affection. I can still make my father blush just by kissing him on the cheek. But since I grew up in America, I have the privilege of being more direct. I found the traditional Chinese characters for ‘We are thinking of you’ and ‘We love you,’ and I wrote them on every container. I thought it was important to use the word ‘we.’ I never signed our own names. Because I wanted it to feel like a whole bunch of people, an entire community who cared. And before long that’s exactly what it was. We found ten restaurant partners within a half mile who helped us prepare culturally relevant foods. And over the past eighteen months Heart of Dinner has delivered 80,000 meals to our Asian elders. We weren’t able to personally write notes on each one. So we put out a call on Instagram, and 100,000 hand-written notes poured in from all over the world. We told people to go wild. Add as much character as you’d like. There were so many styles, and so many colors. But every note had two things, written in big, bold letters: ‘We are thinking of you.’ And ‘We love you.’”

August 26, 2021

(2/2) “Before I left Miami my friend gave me an old Puerto Rican...

(2/2) “Before I left Miami my friend gave me an old Puerto Rican driver’s license. There was no picture back then, just a name: ‘Ramon Alvarez.’ So I decided: ‘My name is now Ray from Puerto Rico.’ In Miami it was warm like heaven. But when I arrived in New York it was snowing. Outside the bus station there was a Jewish guy selling coats for $14. I told him I only have $7, and he says no problem. He hands me a coat. I zipped it up and felt like a million dollars. I walk into a place called YMCA. I tell them: ‘I’m homeless.’ They ask me: “Are you Christian?’ I tell them: ‘Definitely. God bless America.’ And they give me bed to sleep. I go to every bar, every restaurant. I tell them: ‘I need a job.’ Everyone says: ‘No, no. Get out.’ But then one of them says: ‘You are now a pot washer.’ Every day I had to wash 150 pots. But every night the chef gave me a pot of rice. He says: ‘Lock yourself in the closet and eat this.’ Beneath the rice there was steak, and pork, and shrimp! I began to get fat. America, beautiful. One day I walked by an employment agency. I went inside and said: ‘I am Ray from Puerto Rico. I want to be waiter.’ The man tells me: ‘You are now waiter at something called country club in place called New Jersey. You will sleep there. You will eat there. You can use swimming pool, tennis club. And $5,000 a year!’ Oh my God. America, so beautiful. For two years I work at country club. I save every penny. The number in my bank account go up to $10,000. But the manager he has a drug problem. He tells me: ‘Ray, give me $5000 or I call immigration.’ I had no choice. I had to do it. But no problem. America still beautiful. I found a new job parking cars: $5 tip, $2 tip, $1 tip. I spend nothing. I sleep in Volkswagen camper. One day the number in my bank account says $33,000. At the time I had a dream to buy Italian restaurant. But the only restaurant for sale was a place called Andy’s Candy Shop. I knew nothing about candy. But I could learn. So I walked inside, and told the man Andy: ‘I’m here to buy your store.’ He looked at me like I’m crazy. But then I showed him my bank book. And that’s how Andy’s Candy Shop became Ray’s Candy Store. America, beautiful.”

(½) “When I was a baby my stepmother put me on a donkey...

(½) “When I was a baby my stepmother put me on a donkey and sent me to live with my 15-year-old sister. You know what was my toys? Bones and rocks and dust! Each day I got a bowl of water and loaf of bread. As soon as I was old enough I enlisted in the Iranian Navy. I signed up for life. And it was fun for awhile, but after a few years I decided to jump. I wasn’t going to waste my life on a ship. I waited until the perfect moment. We went to India, Pakistan, Spain, Portugal, but I didn’t jump. Then one night we pulled into Norfolk, Virginia. America is rich country. Very beautiful. So I decided to jump. The guards would shoot me if they caught me, but I was ready to die. At 3 AM I jumped into the ocean and swam the half mile to shore. I come out of the water covered in mud. I went to the train station and hopped the next train out of town. It was slow train to town of Miami. Stopped at every American village. When I arrive in the town of Miami the sun was shining, and everyone was driving convertible cars, and football game called Orange Bowl was going on. I walked to the gate of the stadium and said: ‘Please, I’m a Navy Man. Can I go in?’ The man says: ‘Sure. Take any seat you want.’ Oh my God. America, beautiful. Orange Bowl was a strange thing. Big guys hit each other, running ball. I had no idea what was happening. After the game I went to sleep under a bridge. Alligator watching me. Mosquitos eating me all night. In the morning I go to donut shop and wash windows for donuts. For six months I work like this. Clean windows, eat. Clean windows, eat. Then one man offered me a job in coffee factory. Big, heavy bags. No ventilation. Lots of dust. But I was happy. Much better than Iranian hell boat. America, beautiful. But one day big fat belly man come up to me with badge from FBI. He asked me for ID. But I have no ID to show him, so I thought: ‘They’re sending me back to the boat. I’m going to get killed.’ But when we got to the jail they made me pay a $20 fine. They told me: ‘Monday you must come back to court.’ I tell them: ‘Definitely, definitely. I will see you on Monday.’ Then I went straight to the bus station, and got on a bus to town called New York.”

“He ran his last NYC marathon on the day before his final...

“He ran his last NYC marathon on the day before his final surgery. The oncologist told him not to do it. By that time he had a massive tumor on his jaw. He couldn’t even swallow. It took him five hours, but he finished the race. Nobody could tell him to stop. He tried to pass down his love of running, especially when we were little. He signed us up for all the kiddie races. But it never took hold. It wasn’t until college that I decided to run one marathon in Dad’s memory. When I reached the finish line I was hurt, and sore, but I remember thinking: ‘That was easier than I thought.’ And since then I’ve run 33 of them. It isn’t about the finish line anymore. It’s just a part of my life now. Most mornings I wake up at 4 AM and run ten miles to the hospital. I’ll take a quick shower and be on the unit by 7: feeling energized, and resilient. I work in the pediatric ICU, so you have to be resilient. It’s part of the job. But recently I was really tested. I’d just gone through a bad breakup. My brother was in a bad car accident. There was a period when my mental health finally broke down. Everyone gave me grace: Mom called multiple times per day, my friends were incredible, my coworkers pushed me into the back office whenever I needed to cry. But I was so mad at myself. Because I’m a happy person at baseline. I don’t focus on problems. I’m a fixer. I’m always looking for reasons to be grateful: it’s a beautiful day right now, it’s summer, it’s the weekend. I’m the kind of person who appreciates those things. That’s my baseline. It’s who I am. And I was so mad at myself, because for a time I just couldn’t connect with that person. The one thing I did was keep running. No matter how I felt, it’s the one thing that stayed consistent. That’s probably my favorite thing about running. It’s always there. Even if it’s between shifts, and it’s snowing, or your life’s falling apart, you can just put on your sneakers and go. And no matter how lost I felt, there’d always be a moment. It would be 5:30 in the morning, and I’d be halfway to work, and the endorphins would kick in. And there’d be a moment. When I’d come back to baseline. A moment when I felt like myself.”

August 25, 2021

Thanks to everyone who has followed along these last couple days...

Thanks to everyone who has followed along these last couple days as we’ve shared the stories of Grandma Dawn and ‘Mr. Tony’ Hillery of Harlem Grown. I never intended these two stories to be told together. But the connective tissue is obvious: they both are on a mission to help the children in Harlem. There are currently thousands of Harlem children living in shelters. 115,000 city-wide. ‘It’s an epidemic,’ says Tony. ‘An invisible epidemic.’ Grandma Dawn’s dream is to reach every one of these children with books. And Tony’s dream is to reach every one of these children with healthy food and nutrition. Yesterday they came together in a beautiful collaboration. Tony offered to build six small libraries for Grandma Dawn on his urban farms across Harlem. Grandma will curate and stock the libraries from her collection of 25,000 books. She wants to focus on biographical books especially, so the children can see themselves in the characters: “uplifting, positive stories of people who overcome obstacles and do great things.” With your help, we’ve just raised over $300,000 for that mission. Grandma has requested that all further funds go toward Tony’s dream of building a Mobile Teaching Kitchen. Tony is now able to connect with 8% of Harlem’s children with his urban farms. But he wants to reach them all. For each additional $200,000 raised, Tony will be able to staff and supply the Mobile Teaching Kitchen for an entire year, as it provides healthy food and education programs across Harlem. Thanks to everyone who has engaged with these stories, and especially to those who have stepped up to empower these two individuals. And to Tony and Grandma, thank you for providing us with this model of community during a trying time. I encourage everyone to read their stories for a dose of inspiration. And if you would like to contribute to their mission, you may contribute here: https://bit.ly/grandmapromise

(5/5) “Right away I knew I was in trouble. I typed ‘bookmobiles’...

(5/5) “Right away I knew I was in trouble. I typed ‘bookmobiles’ into Google and found an article from 1955. That was almost seventy years ago. And bookmobiles were costing $55,000 even back then. I wanted to run away and hide. I’d been so naïve. Where was I going to park a bookmobile? And who’s going to drive this thing? So many worries were racing through my mind. And I couldn’t even call Winslow anymore, because he’s 97 now. Me and Spike Lee were going to have to figure this out on our own. Because a promise is a promise. And I said it out loud. So I dusted myself off and organized a Bookmobile Block Party on Juneteenth. We had some performers. We had a little raffle. We collected donations. But Grandma had gotten a little too excited again. I rented some DJ equipment. I got 500 bottles of water. And when the smoke had cleared, the Bookmobile Block Party lost money. I mean big time. The whole neighborhood had a great time. They were all saying: ‘What a big success!’ And I was faking it. I was smiling, and dancing. But inside I’m thinking: ‘Oh God, Grandma. What have you done? You lost the rent money.’ I had to pull out my secret stash. Twenty years of struggle, and I never once touched the stash. The stash was off limits. But Grandma is in the stash now. Deep in the stash. There isn’t even a stash anymore. But a promise is a promise. There are nearly 28,000 homeless children in Harlem, and I want them reading books. Because books were my only friends growing up. My mother worked three jobs. My older sister dropped me off at the library so she could run the streets. Books are what showed me that there was another way to live. I saw myself in the characters. They got me thinking that I could improve my life. And whenever I think hard about something, it happens. So every morning I wake up at 4:44 AM. I stare at the ceiling, and I really think about that bookmobile. I see it driving down the street. I see those wheels turning. I see the kids running along the side, waiting for it to stop. I can even see the name, written on the side, in big letters. I can see it, clear as day. It says: ‘GRANDMA’S PROMISE.’”

For weeks we’d been searching for a partner to help Grandma Dawn with her promise. And it was so hard to find a good fit. Turns out there is tons of red tape involved in the operation of a bookmobile. (Not to mention money.) I didn’t even think of asking Tony Hillery until I was publishing Harlem Grown’s story on Sunday. Mr. Tony responded immediately with an offer to build ‘Grandma’s Promise’ libraries on his urban farms. He then offered to include a book collection on his Mobile Teaching Kitchen, serving the exact same children that Grandma dreamed of reaching. It was a match made in heaven. When Grandma went to visit Tony’s garden today, she said a butterfly landed on her. Twice. Double confirmation. This collaboration gives us a unique opportunity to empower two individuals who have devoted their lives to helping the children of Harlem. If you’d like to help fulfill Grandma’s promise, you can contribute here: https://bit.ly/grandmapromise

(4/5) “Nobody ever knew that Grandma was struggling. Because...

(4/5) “Nobody ever knew that Grandma was struggling. Because I’ve never been good at asking for help. But Grandma has always been struggling. Every year they kept raising that rent. Then the pandemic hit, and all my revenue stopped. The landlord didn’t care that this was a literacy center. They just kept charging me rent. But what really broke my heart is when the government said that Grandma’s Place was non-essential. We had to close our doors. That really crushed me bad. All day long I was sitting at home with my dog Spike Lee. I was thinking about all the ‘What If’s’: ‘What if I lose my store? What if I lose my brownstone?’ Then I needed to get heart surgery, and that made me even more depressed. But still, I never asked for help. I didn’t even know how to say: ‘I’m lonely.’ But people started showing up. My neighbor Ron started bringing me breakfast every day. Jah Turner helped me organize my pills. Tariqa Mills helped me file for those grants. And my granddaughter Chelsea was always around to help me think of that word I was searching for. But the best part was the kids. They’d come to the door of Grandma’s Place with tears in their eyes. They’d be ringing the bell, over and over. A lot of times they wanted a toy. But sometimes they just wanted to see Grandma. It made me realize that I am essential. One day my friend Joelle called me up and said: ‘Grandma, don’t be mad. But we organized a GoFundMe.’ And she’s a reporter for Channel 4 News, so she did a story and everything. Then New York Nico shared it on his page. And when everything was finished we’d raised enough money to pay my back rent. I even had $5,000 left over. I felt so loved. I felt so thankful. And I might have gotten a little too excited. Because right then and there I made a promise. I said it out loud. I even told a reporter. I said: ‘I’m going to take this extra $5,000, and I’m going to buy a bookmobile for the children of Harlem.’ Everyone was so happy. I was walking in the clouds. Then later that night I got on my computer and looked up the price of a bookmobile, and I nearly had a heart attack. Oh Lord, Grandma. What have you done? You should have never made that promise.”

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 768 followers