Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 25

January 6, 2022

“One of my spots is ‘showing more density.’ That doesn’t sound...

“One of my spots is ‘showing more density.’ That doesn’t sound good. But the oncologist said we just need to wait. For more growth. For a clearer signal. There’s nothing to do but wait. It’s a fear unlike I’ve ever experienced. I know how aggressive it is. I know what’s going to happen in the end. But I’m trying to trust. That my body is healing the way it should. That the doctors are doing all they can. That the researchers are doing all they can. But it’s hard. And there are definitely days when I question if it’s all worth it: the chemo, the radiation, the side effects. Not that I’d ever stop or anything. But if I’m going to die anyway—why am I doing all this? Those are the harder thoughts. Those days happen. I try not to fight them. But I also try not to sink too deep. Because I want to get past those days. I want to get to a good day. Because good days happen too. Days when I’m present, and I’m not thinking about the future, and I can enjoy little things. A good day is a Sunday in the kitchen, with my dog Delta at my feet. Cooking is my passion. I can make Bolognese sauce all day, even though I’m not a little bit Italian. I usually like to keep the windows open so a little breeze can come through. There’s an enormous fig tree in our neighbor’s yard. The smell is amazing; it’s not the figs themselves, but the smell of the leaves. It’s perfumy, and enveloping, and calming. I wish I could candle it. The figs always bloom in the summer. Which is perfect for me, because the cancer makes me cold. So on hot afternoons my husband and I will head over to grab a bunch of figs. I don’t even think my husband likes figs. But he’s tall so he can help me. He doesn’t actually pick them for me, but he’ll pull down the branches so I can get them myself. Then afterwards we’ll take them home to make a fig jam. That’s a good day. Those still happen. And I want to have as many of them as possible. I hope that spot on my lung doesn’t grow. I really don’t want to go through treatment again. But I will if I have to. It might mean bad days. But I want to stay alive, really. I want to live. I have no idea how long my life is going to be. But I do want to live all of it.”

“One day my youngest daughter wanted to dance. So she put on her...

“One day my youngest daughter wanted to dance. So she put on her sister’s old ballet stuff, and started running around the room. She’s only two, so she’s not fast. But there was a moment when I tried to chase her, and I was immediately out of breath. That’s what brought me in for my first test. The oncologist told me not to google the diagnosis. But I did it anyway, and I learned how aggressive it is. My mind immediately went to my kids. The social worker told us how to give them the news, be honest, find a comfortable setting. But mainly just be honest. We sat them down in the family room, and I don’t even remember what we said to them. Physically I was there, but in my head I was way down the road, looking at the future. Can anyone else love them like me? Can anyone else make them feel safe? Will they be OK without a father? Sometimes I go so far down that road. But my wife and I have this agreement. It’s fine to feel down, and cry. But you just can’t stay in that hole. You have to come back out, and find something positive to focus on. And for me it’s always been our kids. They’re beautiful kids. They’re intelligent, they’re loving. And maybe I’m not going to see them graduate, or dance at their wedding. But right now I’m still able to coach their soccer teams. I can still read them books. So that’s what I’m focusing on. I’m dragging out bedtime just a little bit longer, so we can have a few more minutes every night. Sometimes we’ll go through old videos and pictures on my phone. It’s something we’ve always done. They love looking at themselves when they were super young. But it’s a different experience now. Not different for them, but different for me. I used to look at those old pictures, and think: ‘Yah, we had a great time.’ But now I really see them. Everything that’s being displayed: the joy, the unconditional love. All of it. There’s one picture that always makes me stop. It was taken one week after my diagnosis. I’m with my oldest daughter, at a father/daughter dance in the cafeteria of her preschool. I remember that night so well. We’re dancing in the photo. But I’m not holding her hands, like everyone else. I’m holding onto all of her.”

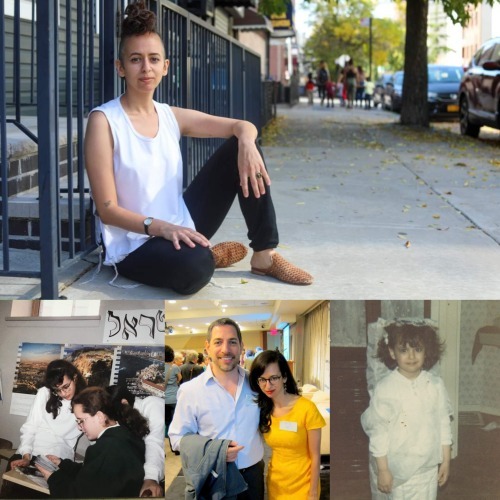

“Whenever she saw me drawing, my mother would tell me to stop....

“Whenever she saw me drawing, my mother would tell me to stop. ‘You’ll be nothing but a poor artist,’ she’d say. Her life was very hard. She worked in a sweatshop, so she wanted me to get a ‘real job’ when I grew up. But art was the only thing I was good at. I was failing all my classes. I couldn’t speak English well. But I’d paint these little watercolors, and it was enough to make my teachers say: ‘Wow.’ When I was fifteen a program came to our school. They were recruiting kids to paint a mural in the courtyard. Ten of us were chosen. The instructor was a man named Arlan Huang. He was a real, working artist. He’d gone to art school. But most importantly he was the first artist I’d ever met who looked like me. My father was not around. So I think I needed someone to latch onto. Arlan brought us to his studio in SoHo, and it was like: ‘Wow! You can do this for a living.’ He taught us about visual storytelling. He taught us how to use symbolism. He taught us to reach down deep, and express a feeling. We were just kids, so these were complicated concepts. The theme of our mural was: ‘Tell your story.’ At the time I lived in the housing projects. So I painted a giant extended hand, with my building coming out of it. It was like: ‘Look at how we live.’ When I finished Arlan told me: ‘This is good. You are good.’ And oh my God. That encouragement carried me through so much. Even when my mother called me a ‘poor artist,’ I kept practicing. I found other teachers who believed in me. And eventually I earned a scholarship to the School of Visual Arts. When the envelope arrived at our house, my mother started crying. Not because she was happy. Because she knew she couldn’t stop me anymore. Even after I got my degree, she couldn’t see the value. She stole that moment from me. She begged me to apply for a job at the post office. It was Arlan that congratulated me. It was Arlan who attended my graduation. Looking back on my entire journey, there is not a moment when I don’t see him. We’re great friends now. And fifteen years ago, when the US Postal Service selected me to paint a series of stamps for the Lunar New Year, it was Arlan that I showed my first draft.”

November 24, 2021

“My town was voted best small town in America. It was very upper...

“My town was voted best small town in America. It was very upper middle class, and white. I was neither of those things. Other kids would touch my hair. I’d look out of the corner of my eye, and they’d always wipe their hand. It would be like: ‘Did that really happen?’ But I never wanted to say anything. Because people in my town were progressive. They weren’t ‘like that.’ I remember climbing a rope swing in gym class, and the teacher started making monkey noises. I’m laughing. I’m trying to be in on the joke, but it’s painful. I felt so othered. Being gay didn’t help things. I was afraid of the bus ride. Afraid of the cafeteria. The only time I felt confident was when I was doing drugs: first cocaine, then crystal meth. Drugs made me feel whole; even if I was emaciated, even if I hadn’t slept in six days. In 2010 I finally entered recovery. I’d met a lot of black and brown users on the streets, but these meetings were all white people. Recovery is about being honest. But my trauma was racial. And this didn’t feel like a safe place to express that. I sat in the back. I didn’t speak up. Michael was the opposite of me. He was black, and queer, and HIV positive, but he wasn’t embarrassed. He was very: ‘This is who I am.’ He’d just joined the seminary. He was reading James Baldwin. He was being mentored by Cornell West. He was on a high. After one meeting he gathered the black members of the group, and said: ‘Why don’t we have brunch?’ There were four of us. We met at Michael’s apartment in Harlem. We could finally speak about how racism fueled our addictions. But it was more about what wasn’t said. We laughed, and cried. Our bodies relaxed in a way they’d never relaxed before. Since then our group has grown to over 30 black, queer former meth addicts. We meet every month. We have lunch. We take trips together. Last Sunday we had a ‘Friendsgiving’ thing. At the end of that first meeting, Michael gave us a prompt: ‘What does this mean to you?’ And each of us were given five minutes to speak. ‘I was super afraid of coming here,’ I said. ‘Because I didn’t feel black enough. I’ve never had close black friends. But this is what I’ve been looking for my whole life.’”

“I still have the original flyer that I made: 100 suits for 100...

“I still have the original flyer that I made: 100 suits for 100 gang members. At the time I was working as a bank teller. My manager allowed me to put a collection box in the lobby. People donated so many suits that I had to move them to the staff closet. I got written up for that, so I moved them all to my bedroom. Nothing in there but a bed and one hundred suits. We handed all of them out that very first day. I brought a suit rack to where all the kids hang out on the corner. I gave each kid a hair-cut: line-up, fade, I can do it all. Then afterward I’d fit him for a suit. Take a young man without any hope, and put him in a suit jacket, and a tie. He’s going to change his opinion of himself. He’s going to feel like he’s CEO of the world. I brought along one of those cheap ten-dollar mirrors. I’d show him his reflection. Then I’d send him straight to the job development person. I had no idea what I was doing. I had no clue what it would grow to be. Over the last ten years we’ve given out 50,000 suits. Whenever a man needs a fresh start, we’re there with a suit. We’ve partnered with prisons, and parole, and gun buyback programs. I’ve learned a lot since that first day. The suit can’t be the end all. It’s just the carrot being dangled. We do a lot of leadership training. And job development. We have a peace room in our office. It is what it is. A space of zen. There’s a waterfall in there. When a young man loses a friend to violence, he needs to know it’s OK to cry. It’s OK to talk. I try to set an example. I’ll talk about my own trauma. There was an entire month in 2016 when I was homeless. Every night I slept in my car, in the parking lot of JFK. I was too embarrassed to tell anyone. But I kept doing what I do. We’d just started our partnership with parole, so I was doing a lot of suiting. Each morning I’d wash up in the bathroom of the travel center. I’d put on black pants, and a $5 black t-shirt. And I drove to work. I kept a single suit jacket behind my desk. First thing in the morning I’d slip it on, and I’d get a boost. No matter what was going on. No matter how low I felt. When I slipped on that jacket, for a moment I’d feel like CEO of the world.”

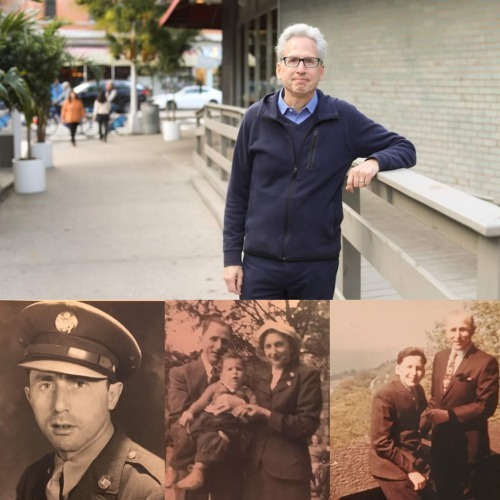

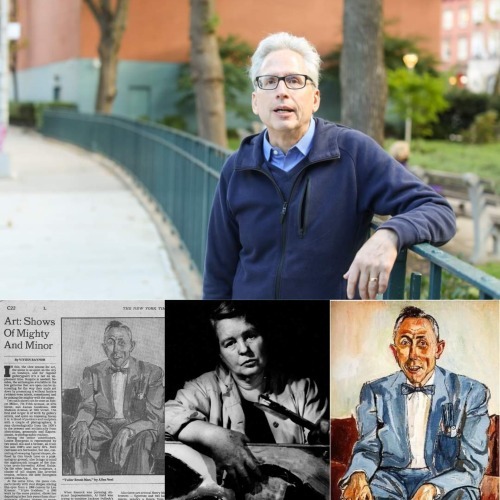

(4/4) “He’d been a successful salesman in Germany, before Hitler...

(4/4) “He’d been a successful salesman in Germany, before Hitler tightened the vice. I have a picture of him with a 1935 Mercedes Benz, and a chauffeur. I have pictures of him partying at upscale resorts. But he got caught in the first wave of deportations. He spent two months at Dachau, doing forced labor in the middle of winter. But Dad was one of the lucky ones. Hitler was still allowing Jews to leave the country, if they gave up all their possessions. So he escaped to America, carrying only two trunks. Then he turned right around. He went right back. He joined the American army and fought in the Battle of The Bulge. And afterwards he became a Fuller Brush Man. For the next 25 years he knocked in the snow. He knocked in the rain. And he never complained. There might have been a hint of ‘what might have been.’ But he was happy. He loved this country. He loved his family. And his job did its job. I wish I’d asked him more about his past. He only told one or two stories about it. I remember him saying that he wore rags for a coat. But that was all he told us. I guess he was trying to protect us. A few years ago I took my family on a trip to Germany. I wanted it for my kids. We visited my father’s hometown. And then we went to Dachau. It was one thing to read about it. To see it on the label of a painting. But it was another thing to be there. To retrace his steps. To see the induction room, where they make you strip, shower, shave off all your hair. Where they give you a label: Gypsy, Catholic, Jew. Where they take away your name, and you become unhuman. Not inhuman. Unhuman. It answered a lot of questions for me. I could see why Dad loved this country so much. And why even on his toughest days, knocking on doors, he was happy to be here. He was the happiest of Alice Neel’s paintings. Thirty years ago I had the chance to buy it. I could have owned Fuller Brush Man. But I don’t think about it much. I’m not sure what good it would have done me, anyway. Because I’d never be able to sell it. No matter what it could have fetched. Ten million, one hundred million, I’d never be able to give it up. How could I? It would be like selling a member of my own family.”

(¾) “Alice Neel was known as ‘the collector of souls.’...

(¾) “Alice Neel was known as ‘the collector of souls.’ She painted all kinds of people. But if you look at her other work, the subject of every painting has a name: Olivia, Linda, Kenneth. Everyone except my father. He was just called Fuller Brush Man. It bothered me. He was so much more than his job. He wasn’t some generic salesman. He was my dad. I wrote a letter to the curator of the Whitney. I said: ‘Your show is amazing. But I’m the son of Fuller Brush Man. And his name is Dewald Strauss.’ She wrote a nice reply. And when the show travelled next to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, my father’s name was on the label. I rode the Amtrak down to see it. I brought my two sons. It was a huge moment for me. And for the twenty years since, whenever Fuller Brush Man has been displayed, my father has been named on the label. This summer the painting hung in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I went to see it about ten or twelve times. I’d stand across the gallery and watch people as they enjoyed the painting. Sometimes they’d only stop for a moment. But other times they’d pause, and study it. If you ask any curator, they’ll tell you the same thing: Fuller Brush Man is unique. Neel’s subjects are practically all somber and down. But my father has this smile. This aura of optimism. Pride, really. It’s pride. It’s the face he made when he was feeling proud. One time we went to temple for Rosh Hashanah, and the shofar player was sick. The shofar is this ancient horn. So my father said: ‘Let my son do it. He plays the trumpet. I bet Jerry can do it.’ I’ll never forget it. There I was, fifteen years old, on the highest holiday of the year, playing the shofar in front of the entire temple. I looked out in the audience, and there’s my dad. And he’s got this face. Like: ‘Wow, that Jerry. He’s Ok.’ The label hanging in The Met was the best one yet. It said: ‘Dewald Strauss escaped from Dachau and immigrated to America. He returned to Germany as an Allied soldier, earning a Purple Heart for his service. With his alert stance and open expression, Strauss meets Neel’s gaze with clear-eyed sincerity, revealing an unabashed positivity in his eager pursuit of the American dream.”

(2/4) “It was an article announcing a new gallery show by the...

(2/4) “It was an article announcing a new gallery show by the painter Alice Neel. Only one of her paintings was shown in the article. It was titled: ‘Fuller Brush Man.’ And it was Dad. Physically there were some exaggerations, because that was Neel’s style. The hands were prominent. So were the folds in his suit. But the face was unmistakable. She nailed it: the smile, the upbeat gleam in his eyes. It was my father. It didn’t take me long to figure out what had happened. Neel’s studio was on 107th Street. That was Dad’s territory. Alice Neel must have been his customer. That weekend my wife and I drove down to the show. It was at a fancy, downtown gallery. The painting was striking, and it was for sale. We could have owned it. But it was $35,000. We just couldn’t do it. It’s probably worth millions today. Three months after the show Alice Neel passed away. I never got a chance to meet her. Over the years I’d occasionally see an article about her work, but life got busy for me. I had two children of my own. And that’s when I really started missing Mom and Dad. My wife’s parents were around. My sons had this great relationship with them. But I had to reconstruct my parents in absentia. All I could say was: ‘You have these other grandparents, and they would have loved you so much.’ Both my sons are grown now. They’re older than I was when Dad passed away. And my relationship with them has evolved. It’s still father-son. But it’s father, and adult son. We can get a beer together. We have real conversations: about the world, and politics, and graduate school. My dad and I never made it that far. He’d tell me these stories, and I was kinda listening. I knew what happened to him back in Germany. But I didn’t really know. I was a teenager. I wanted to go out. And he was just my dad. On the 100th anniversary of Alice Neel’s birth there was a huge retrospective of her work at The Whitney. Seventy-five paintings. A massive advertising campaign. Dad’s picture was everywhere: in the newspaper, on the subway. I’d be walking down Madison Avenue, and the number four bus would whiz past, and there’s Dad, blown up on the side. Except nobody knows it’s Dad. He’s just ‘Fuller Brush Man.”

(¼) “He’d knock in the rain. He’d knock in the snow. He’d...

(¼) “He’d knock in the rain. He’d knock in the snow. He’d come home late on these dreadful winter nights, and my mother would have his slippers under the radiator and his bathrobe on top. In the 1960’s Fuller Brush was the dominant name in door-to-door sales. It was the milkman, the newspaperman, and the Fuller Brush Man. And my father was a Fuller Brush Man. It was a tough job. Many nights he’d come home empty-handed. There were weeks we’d have less meat and more potatoes, but he never complained. That’s one thing he always taught me: ‘Don’t go too crazy on the material things.’ Maybe knocking on doors wasn’t the best job, but the job did its job. It helped him raise a family. On Fridays he’d take me with him while he made deliveries. Those were my favorite days. I’d spend the whole afternoon with Dad. And Friday night was the sabbath, so we both knew there’d be an amazing German-Jewish dinner waiting for us at home. Dad hadn’t gotten married until after the war, so there was a literal generation gap between us. But he encouraged me the best he could. He bought me my first trumpet when I was thirteen. Every time I played a solo, he’d take me out for ice cream. In high school I started a little rock band with my friends. It wasn’t Dad’s type of music. But he’d let us practice in our tiny apartment. He’d help us load equipment. By then he was 65, but he’d be carrying drum sets and amplifiers in and out of social halls and sweet sixteen parties. Dad died suddenly of a heart attack when I was a freshman in college. Mom’s lungs were already filling up with cancer, and two years later she’d be gone too. At the age of twenty-one I was on my own. I never really had time to mourn. I did what my dad would have done. I tried to stay positive. I put one foot in front of the other: I went to college, I went to grad school, I got a job. Then one afternoon I came home from work, and I got a call from my cousin Linda. She said: ‘Are you sitting down? Because your father is in today’s New York Times.’ Dad had been gone for ten years. It didn’t make any sense. But I ran out to the newspaper stand, and opened up a copy of the Times. And there he was. Staring back at me.”

November 18, 2021

“My father had his own special chair that nobody else was...

“My father had his own special chair that nobody else was allowed to sit in. We were taught that he was holy and spoke for God. During a blessing he might kiss me on top of the head, and that was like wow. But there were no ‘I love yous’ in our home. On Friday nights we’d go to his synagogue, and my favorite part of the service was a song called Lecha Dodi. It means ‘Come My Beloved,’ and it’s a love song to God. My life was so devoid of affection, that song was like water in the desert for me. I was raised to be the wife of a rabbi. Nobody checked my homework, or cared about my grades. When I told my mother I wanted to go to college, she threatened to call the psychiatrist. That was the beginning of my rebellion. I left home and started working as a cleaning lady. I had no community, nothing. I’d only ever known a world where God is male, and our leaders are male. I was so vulnerable. I ended up getting raped. There was a lot of trauma. And at the same time I was dealing with this great sense of spiritual loss. It was actually in a support group for ex-orthodox where I learned about Romemu. My friend said: ‘I know everything Jewish is toxic, but give this synagogue a try.’ The service was held in a former church. And the first thing the Rabbi said was: ‘We welcome every one of every faith, or no faith.’ His name was David. He was a wounded healer. He’d also grown up Orthodox. He’d been abused as a child. ‘Some of us have been traumatized by God,’ he said. And I needed to hear that. Because in that moment I felt so broken. Most adults get to be evolved versions of their childhood self. But my childhood was a severed path, a foreign country. Nobody from there wanted to talk to me. Everything that once seemed holy, now seemed cruel. But David provided an access point to God that wasn’t toxic. He taught the same texts, and same parables. But his interpretations were different. More tolerant. More progressive. During that first service we sang ‘Lecha Dodi.’ I closed my eyes. And I had this vision of myself as a child, singing in my father’s synagogue. It’s almost like the two of us were singing together. We finally had permission to exist at the same time.”

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 768 followers