Tyson Adams's Blog, page 31

November 13, 2018

November 11, 2018

Scarface Claw – Too Serious

This time last year (2017) my family and I attended the book launch of the latest instalment in the Hairy Maclary (from Donaldson’s Dairy) series by Lynley Dodd. Hairy Maclary and his friends have been entertaining people, particularly younger people with an as yet undeveloped world-weariness, for 30 years. The latest book in the series is titled Scarface Claw, Hold Tight! and I’m left with some very important questions.

For those who aren’t aware, Scarface Claw is the toughest tomcat in the town where Hairy Maclary and his friends live. Which town this happens to be and the relative toughness of the other tomcats living there is not explored in any detail in the series, which could be regarded as an oversight. Scarface Claw has, on more than one occasion, threatened or utilised violence against the cats and dogs in town. This has seen scatters of paws and clatters of claws from Schnitzel von Krumm with a very low tum, Bitzer Maloney all skinny and bony, Muffin McClay like a bundle of hay, Bottomley Potts covered in spots, Hercules Morse as big as a horse, and Hairy Maclary from Donaldson’s Dairy.

Obviously, this nasty, violent, and abusive cat makes for an ideal protagonist in a children’s book. Scarface Claw, Hold Tight! marks the tomcat’s second outing as the hero.

[image error]

This adventure sees our cranky and crotchety hero sunning himself on top of Tom’s car. Somehow, Tom manages to not see the rather large black tomcat sprawled on the roof of his red car and hurries off to somewhere very important – another detail unexplored by the narrative. Since this is the inciting incident of the story, you would expect it to be more believable. Are we to seriously believe that Tom doesn’t notice old Scarface? As we soon discover, literally everyone else in the town notices Scarface Claw clinging to the roof of the car, so either Tom should be required to acquire prescription lenses for driving or he knew Scarface Claw was there all along.

That Tom knowingly drove around town with a cat on his roof is not inconceivable. Scarface Claw has a long and infamous history, particularly amongst the resident town pets, so mistreatment of the tomcat may be a common occurrence. It may be that this mistreatment is what makes Scarface Claw the nasty cat he is. Maybe with extensive therapy, Scarface Claw could become a lovable and friendly cat who would be invited to Slinky Malinky’s house in a tail waving line. We can only hope.

We also have to question why everyone in town noticed Scarface Claw clinging to the roof and wanted to “rescue that cat”. Presumably, the townfolk recognised Scarface Claw, so either they are more kind and caring than Tom – plausible given my previous points about potential mistreatment – or they are starved for excitement such that waving a sock at a driver with a cat on his car roof would make it into a lifetime highlights list. But that doesn’t excuse the next issue.

I know that many animal lovers would support the use of police and fire and rescue for animal emergencies, but you have to question Constable Chrissie’s response. Did the Constable honestly have nothing better to do with her time than pull Tom over? What laws has he broken? If Tom has broken some laws, why wasn’t he charged with an offence? And why didn’t she call for a licensed animal controller, such as the Ranger, instead of relying on the ever conveniently helpful Miss Plum?* Does Constable Chrissie suspect that Tom is an abusive pet owner and is wanting to compile a list for a potential animal welfare case?**

There are so many questions left unanswered, so many details not covered, that I am left at a loose end. I can only hope that future books in the series will address these issues in some way.

*Miss Plum has a long habit of helping the town pets out of their adventurous mishaps. She seems to always conveniently arrive in the nick of time. A more suspicious person would suspect that something more sinister is at play here. Is Miss Plum stalking the town pets? Is she behind the pets’ misadventures? Hopefully, these questions will be addressed in later instalments in the series.

**Or at least intervene where possible to stop animal abuse events.***

***And it is possible that Constable Chrissie keeps an eye on Tom and his activities – possibly Miss Plum does as well – because she suspects Tom’s animal abuse may morph into something more serious. Best to catch a killer early.

November 8, 2018

How speculative fiction gained literary respectability

Biologists are gathering evidence of green algae (pictured here in Kuwait) becoming carbohydrate-rich but less nutritious, due to increased carbon dioxide levels. As science fiction becomes science fact, new forms of storytelling are emerging.

Raed Qutena

I count myself lucky. Weird, I know, in this day and age when all around us the natural and political world is going to hell in a handbasket. But that, in fact, may be part of it.

Back when I started writing, realism had such a stranglehold on publishing that there was little room for speculative writers and readers. (I didn’t know that’s what I was until I read it in a reader’s report for my first novel. And even then I didn’t know what it was, until I realised that it was what I read, and had always been reading; what I wrote, and wanted to write.) Outside of the convention rooms, that is, which were packed with less-literary-leaning science-fiction and fantasy producers and consumers.

Realism was the rule, even for those writing non-realist stories, such as popular crime and commercial romance. Perhaps this dominance was because of a culture heavily influenced by an Anglo-Saxon heritage. Richard Lea has written in The Guardian of “non-fiction” as a construct of English literature, arguing other cultures do not distinguish so obsessively between stories on the basis of whether or not they are “real”.

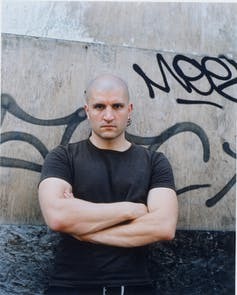

China Miéville in 2010.

China Miéville in 2010.Pan MacMillan Australia/AAP

Regardless of the reason, this conception of literary fiction has been widely accepted – leading self-described “weird fiction” novelist China Miéville to identify the Booker as a genre prize for specifically realist literary fiction; a category he calls “litfic”. The best writers Australia is famous for producing aren’t only a product of this environment, but also role models who perpetuate it: Tim Winton and Helen Garner write similarly realistically, albeit generally fiction for one and non-fiction for the other.

Today, realism remains the most popular literary mode. Our education system trains us to appreciate literatures of verisimilitude; or, rather, literature we identify as “real”, charting interior landscapes and emotional journeys that generally represent a quite particular version of middle-class life. It’s one that may not have much in common these days with many people’s experiences – middle-class, Anglo or otherwise – or even our exterior world(s).

Like other kinds of biases, realism has been normalised, but there is now a growing recognition – a re-evaluation – of different kinds of “un-real” storytelling: “speculative” fiction, so-called for its obviously invented and inventive aspects.

Feminist science-fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin has described this diversification as:

a much larger collective conviction about who’s entitled to tell stories, what stories are worth telling, and who among the storytellers gets taken seriously … not only in terms of race and gender, but in terms of what has long been labelled “genre” fiction.

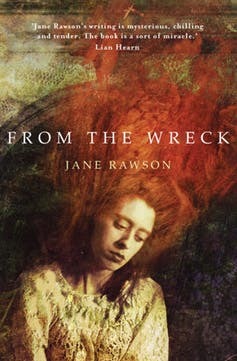

Closer to home, author Jane Rawson – who has written short stories and novels and co-authored a non-fiction handbook on “surviving” climate change – has described the stranglehold realistic writing has on Australian stories in an article for Overland, yet her own work evidences a new appreciation for alternative, novel modes.

Rawson’s latest book, From the Wreck, intertwines the story of her ancestor George Hills, who was shipwrecked off the coast of South Australia and survived eight days at sea, with the tale of a shape-shifting alien seeking refuge on Earth. In an Australian first, it was long-listed for the Miles Franklin, our most prestigious literary award, after having won the niche Aurealis Award for Speculative Fiction.

The Aurealis awards were established in 1995 by the publishers of Australia’s longest-running, small-press science-fiction and fantasy magazine of the same name. As well as recognising the achievements of Australian science-fiction, fantasy and horror writers, they were designed to distinguish between those speculative subgenres.

Last year, five of the six finalists for the Aurealis awards were published, promoted and shelved as literary fiction.

A broad church

Perhaps what counts as speculative fiction is also changing. The term is certainly not new; it was first used in an 1889 review, but came into more common usage after genre author Robert Heinlein’s 1947 essay On the Writing of Speculative Fiction.

Whereas science fiction generally engages with technological developments and their potential consequences, speculative fiction is a far broader, vaguer term. It can be seen as an offshoot of the popular science-fiction genre, or a more neutral umbrella category that simply describes all non-realist forms, including fantasy and fairytales – from the epic of Gilgamesh through to The Handmaid’s Tale.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: the Epic of Gilgamesh

While critic James Wood argues that “everything flows from the real … it is realism that allows surrealism, magic realism, fantasy, dream and so on”, others, such as author Doris Lessing, believe that everything flows from the fantastic; that all fiction has always been speculative. I am not as interested in which came first (or which has more cultural, or commercial, value) as I am in the fact that speculative fiction – “spec-fic” – seems to be gaining literary respectability.

(Next step, surely, mainstream popularity! After all, millions of moviegoers and television viewers have binge-watched the rise of fantastic forms, and audiences are well versed in unreal onscreen worlds.)

One reason for this new interest in an old but evolving form has been well articulated by author and critic James Bradley: climate change. Writers, and publishers, are embracing speculative fiction as an apt form to interrogate what it means to be human, to be humane, in the current climate – and to engage with ideas of posthumanism too.

These are the sorts of existential questions that have historically driven realist literature.

According to the World Wildlife Fund’s 2018 Living Planet Report, 60% of the world’s wildlife disappeared between 1970 and 2012. The year 2016 was declared the hottest on record, echoing the previous year and the one before that. People under 30 have never experienced a month in which average temperatures are below the long-term mean. Hurricanes register on the Richter scale and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology has added a colour to temperature maps as the heat keeps on climbing.

Science fiction? Science fact.

A baby Francois Langur at Taronga Zoo in June. François Langurs are a critically endangered species found in China and Vietnam.

A baby Francois Langur at Taronga Zoo in June. François Langurs are a critically endangered species found in China and Vietnam.AAP Image/Supplied by Taronga Zoo

What are we to do about this? Well, according to writer and geographer Samuel Miller-McDonald, “If you’re a writer, then you have to write about this.”

There is an infographic doing the rounds on Facebook that shows sister countries with comparable climates to (warming) regions of Australia. But it doesn’t reflect the real issue. Associate Professor Michael Kearney, Research Fellow in Biosciences at the University of Melbourne, points out that no-one anywhere in the world has any experience of our current CO2 levels. The changed environment is, he says – using a word that is particularly appropriate for my argument – a “novel” situation.

Elsewhere, biologists are gathering evidence of algae that carbon dioxide has made carbohydrate-rich but less nutritious. So the plankton that rely on them to survive might eat more and more and yet still starve.

Fiction focused on the inner lives of a limited cross-section of people no longer seems the best literary form to reflect, or reflect on, our brave new outer world – if, indeed, it ever was.

Whether it’s a creative response to catastrophic climate change, or an empathic, philosophical attempt to express cultural, economic, neurological – or even species – diversification, the recognition works such as Rawson’s are receiving surely shows we have left Modernism behind and entered the era of Anthropocene literature.

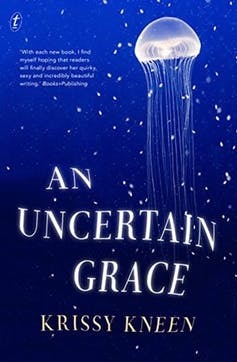

And her book is not alone. Other wild titles achieving similar success include Krissy Kneen’s An Uncertain Grace, shortlisted for the Aurealis, the Stella prize and the Norma K. Hemming award – given to mark excellence in the exploration of themes of race, gender, sexuality, class or disability in a speculative fiction work.

Kneen’s book connects five stories spanning a century, navigating themes of sexuality – including erotic explorations of transgression and transmutation – against the backdrop of a changing ocean.

Earlier, more realist but still speculative titles (from 2015) include Mireille Juchau’s The World Without Us and Bradley’s Clade. These novels fit better with Miéville’s description of “litfic”, employing realistic literary techniques that would not be out of place in Winton’s books, but they have been called “cli-fi” for the way they put climate change squarely at the forefront of their stories (though their authors tend to resist such generic categorisation).

Both novels, told across time and from multiple points of view, are concerned with radically changed and catastrophically changing environments, and how the negative consequences of our one-world experiment might well – or, rather, ill – play out.

Catherine McKinnnon’s Storyland is a more recent example that similarly has a fantastic aspect. The author describes her different chapters set in different times, culminating – Cloud Atlas–like, in one futuristic episode – as “timeslips” or “time shifts” rather than time travel. Yet it has been received as speculative – and not in a pejorative way, despite how some “high-art” literary authors may feel about “low-brow” genre associations.

Kazuo Ishiguro in 2017.

Kazuo Ishiguro in 2017.Neil Hall/AAP

Kazuo Ishiguro, for instance, told The New York Times when The Buried Giant was released in 2015 that he was fearful readers would not “follow him” into Arthurian Britain. Le Guin was quick to call him out on his obvious attempt to distance himself from the fantasy category. Michel Faber, around the same time, told a Wheeler Centre audience that his Book of Strange New Things, where a missionary is sent to convert an alien race, was “not about aliens” but alienation. Of course it is the latter, but it is also about the other.

All these more-and-less-speculative fictions – these not-traditionally-realist literatures – analyse the world in a way that it is not usually analysed, to echo Tim Parks’s criterion for the best novels. Interestingly, this sounds suspiciously like science-fiction critic Darko Suvin’s famous conception of the genre as a literature of “cognitive estrangement”, which inspires readers to re-view their own world, think in new ways, and – most importantly – take appropriate action.

A new party

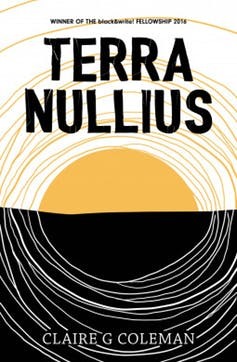

Perhaps better case studies of what local spec-fic is or does – when considering questions of diversity – are Charlotte Wood’s The Natural Way of Things and Claire Coleman’s Terra Nullius.

The first is a distinctly Aussie Handmaid’s Tale for our times, where “girls” guilty by association with some unspecified sexual scenario are drugged, abducted and held captive in a remote outback location.

The latter is another idea whose time has come: an apocalyptic act of colonisation. Not such an imagined scenario for Noongar woman Coleman. It’s a tricky plot to tell without giving away spoilers – the book opens on an alternative history, or is it a futuristic Australia? Again, the story is told through different points of view, which prioritises collective storytelling over the authority of a single voice.

Read more:

Friday essay: science fiction’s women problem

“The entire purpose of writing Terra Nullius,” Coleman has said, “was to provoke empathy in people who had none.”

This connection of reading with empathy is a case Neil Gaiman made in a 2013 lecture when he told of how China’s first party-approved science-fiction and fantasy convention had come about five years earlier.

Neil Gaiman.

Neil Gaiman.Julien Warnand/EPA

The Chinese had sent delegates to Apple and Google etc to try to work out why America was inventing the future, he said. And they had discovered that all the programmers, all the entrepreneurs, had read science fiction when they were children.

“Fiction can show you a different world,” said Gaiman. “It can take you somewhere you’ve never been.”

And when you come back, you see things differently. And you might decide to do something about that: you might change the future.

Perhaps the key to why speculative fiction is on the rise is the ways in which it is not “hard” science fiction. Rather than focusing on technology and world-building to the point of potential fetishism, as our “real” world seems to be doing, what we are reading today is a sophisticated literature engaging with contemporary cultural, social and political matters – through the lens of an “un-real” idea, which may be little more than a metaphor or errant speculation.

Rose Michael, Lecturer, Writing & Publishing, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

November 6, 2018

Book review: Bleak Harbor by Bryan Gruley

Bleak Harbor: A Novel by Bryan Gruley

Bleak Harbor: A Novel by Bryan Gruley

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

If you received a dollar for everytime someone said “X business is a license to print money” you’d have the first instance of that statement being true.

On the day before the Dragonfly Festival in Bleak Harbor, Danny Peters goes missing. Pete Peters, his stepdad, is having a quick beer after work at his medicinal marijuana shop before he and Danny go fishing when he receives a strange text message. Carey Peters is halfway through her long commute, thinking of her work problems, when she receives the message. At first, they aren’t sure if Danny has run off again or if something more sinister has happened until they receive the photo. But which of their secrets has gotten Danny in trouble?

From the very start, we see that this mystery will be built upon the layers of secrets Danny’s parents have been keeping. The twists and turns this gives us are tightly woven together. Pete and Carey feel like painfully human characters stumbling through life and now stumbling through the disappearance of their son. Danny is a refreshing and interesting portrayal of someone with autism, steering clear of the usual cliches and errors.

But I really did find it hard to engage with this novel. I liked Danny, but Pete and Carey weren’t particularly interesting or charismatic. It is hard to follow along with their trials and tribulations when you just want to slap them and tell them to talk to one another. As a result, it was hard to give this more than three stars despite how well the mystery was structured and the book was written.

I received an advance review copy of this book in exchange for a fair review.

November 4, 2018

Book review: Choke by Stuart Woods

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Given the title, you’d think at least one person would be strangled in this story.

Former Wimbledon contender and now tennis club pro, Chuck Chandler, has moved to Key West after sleeping with the wrong person’s wife. Learning from his recent lesson, he starts sleeping with someone else’s wife. This does not end well and he’s soon in the frame for murder. A retired NYC homicide detective, Tommy Sculley, is seeing out his days as the Key West detective training a local rookie. He thinks there is more to this murder than Chuck’s philandering would suggest. A lot more.

In my efforts to explore my local library’s offerings, I came across NYT Bestselling Author Stuart Woods. I didn’t really have any expectations and was rewarded with as much. The twist was something I figured out before the first murder. Admittedly, I didn’t pick the entirety of the finale, but those extra details were window dressing. Figuring out the twist that early would have been fine if the rest of the novel was more compelling, but it just wasn’t. An example of this is that the two main characters – Chuck and Tommy – aren’t particularly interesting. How can you make a philandering tennis pro boring?

To summarise, Choke was only okay. It was just interesting enough to keep you reading but once you’ve finished you can’t think of anything noteworthy about it. Well, except that the local tennis pro is probably trying to have sex with your wife.

October 28, 2018

October 25, 2018

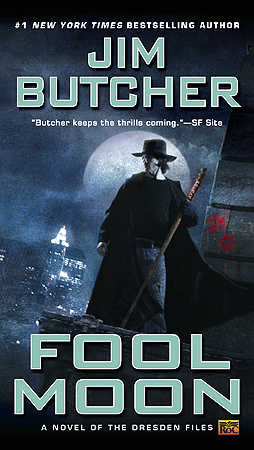

Book Review: Fool Moon by Jim Butcher

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

The chief said, ‘I’m going to need your badge, your gun, and your ability to turn into a werewolf.’

Harry Dresden is living on the memory of ramen noodles and hasn’t heard from his contact at the Chicago Police in ages. But with the full moon dawning, a spate of murders leads Lieutenant Murphy to call on his wizard skills. With the FBI sticking their nose in, Murphy under investigation, and a pack of werewolves on the prowl, Harry is up to his neck in trouble before the moon has risen.

Jim Butcher really does love to make Harry suffer. He is obviously a big believer in creating a large stack of insurmountable odds for each of Dresden’s adventures. This is both entertaining and frustrating. Entertaining because it keeps the suspense up. Frustrating because you kinda want there to be fewer fires layered under the frypan Dresden falls out of. Or to put it another way, you start asking, ‘Isn’t it time to kill the bad guys yet?’ Or to put it another way, the damned suspense nearly killed me.

This was another enjoyable Dresden adventure. I’m looking forward to my next one.

October 23, 2018

How many famous states does Australia have?

All of the Australian states and territories are famous, but for varying reasons. I’ll focus on the six main states and the two mainland territories, because I don’t know anything about the other places.

Australian Capital Territory (ACT): famous for being infested with politicians and bureaucrats. In keeping with tradition, the Aboriginal lands of Kamberra – meaning ‘meeting place’ – were stolen and renamed Canberra when we built our nation’s capital there.

New South Wales (NSW): famous for containing Sydney, the only Aussie city foreigners know, and the only part of Australia Sydney-siders think exists. Also, a great place for backpackers to rest for eternity in a state forest.

Northern Territory (NT): made famous, for better or worse, by Crocodile Dundee. Also famous for the highest (or nonexistent for a short while) speed limits on highways that results in four times the road death toll.

Queensland (QLD): famous for being approximately 50 years behind the rest of the country and being incredibly proud of that fact. See Katter Australia Party and Pauline Hanson’s One Nation for a clearer picture.

South Australia (SA): famous for their banking and barrels. Adelaide is okay.

Tasmania (Tas): famous for having lots of trees and people trying to save them. Also famous for gun control.

Victoria (Vic): famous for not being New South Wales. The state capital, Melbourne, is similarly famous for not being Sydney.

Western Australia (WA): famous for being so far away from everywhere else. Also has lots of mines and people wearing hi-vis clothing.

This post originally appeared on Quora.

October 21, 2018

Book vs Movie: Dracula – What’s the Difference?

[image error]

Since the annual American lolly festival is almost upon us, Cinefix is covering one of the classics. Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Francis Coppola’s 1992 Dracula.

Time for some straight talk. I don’t know how you discuss this particular adaptation without mentioning just how bad Keanu Reeves is in this film. Embarrassingly bad.

I actually tried to rewatch Dracula a couple of years ago and just couldn’t bring myself to sit through it all. Despite it being a bit of a who’s who of actors in the cast – and people like Tom Waits – it all feels so camp and silly. Even when I first saw it in high school, I remember Dracula being only average – with possibly the best visual explanation of the link between Dracula and Vlad the Impaler ever.

It is harder for me to talk about the book as I read it so long ago. And, let’s be honest here, I’ve since read way too many Anne Rice novels to not get the details confused. I read Dracula and Frankenstein at roughly the same time; because gothic horror novels are what pre-teen kids should be reading. Neither stood out for me as novels, but it is amazing how influential they have both been to genre fiction.

I wonder if there will be any modern equivalent. A novel that establishes an entire genre that is continuously reimagined, refined, and redefined such that we get analogues ranging from True Blood (coming out of the closet analogy) to Buffy (girl power).

October 18, 2018

Book review: The Carpet People by Terry Pratchett

The Carpet People by Terry Pratchett

The Carpet People by Terry Pratchett

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

‘Don’t do that! You’ll disturb the carpet people.’

The Munrungs have just had their village destroyed by fray, a natural phenomenon from above The Carpet. In the aftermath, Glurk and Snibril try to help their village flee the attacking Mouls, a people who regard all others as animals and rather good eating. It is then they realise that fray is pushing a path of destruction through The Carpet and that the Mouls are attacking every city and town in its wake. Can they save civilisation so that people don’t go back to hitting each other?

While I was reading this novel I kept having to remind myself that it was the heavily revised edition written by the 40-something Pratchett, not the 20-something of the original edition. This was Pratchett’s first novel and as an ode to fantasy fiction had just the right amounts of absurdism and humour, which I can’t see a 20-something nailing. If Pratchett was this good out of the gate then every other author would be left weeping into the keyboard. Hopefully, someone who has read both versions can point out the differences.

This is, of course, not a Discworld novel. Apparently, all reviewers have to point this out for some reason. As such, Pratchett’s style, particularly his satire, is less pronounced here. While I thoroughly enjoyed reading The Carpet People, for long-time Discworld fans this may feel a little light or insubstantial. Or maybe they just feel guilty about having vacuumed their house.