Tyson Adams's Blog, page 29

January 3, 2019

Book vs Movie: Hellboy – What’s the Difference?

[image error]

This month’s instalment of What’s the difference? from CineFix looks at Mike Mignola’s graphic novel and Guillermo Del Toro’s Hellboy?

In the interest of full disclosure, I’m not a fan of Hellboy: movie or comic. Yes, I know, how dare you not love Del Toro’s amazing artistic vision! I’ve watched both Hellboy movies multiple times and have not loved them (and despite liking the Blade trilogy, Blade 2 isn’t my favourite – but Pan’s Labyrinth was fantastic). The comics I probably didn’t give them a fair chance, as I tried reading one omnibus after not enjoying the first film.

Anyway, the point I wanted to highlight from the video was something I think too many adaptations fail to do. When you are talking about a series of comics or books, there is often some prevailing themes, motifs, and imagery to them that may be less noticeable in any one edition, but taken as a whole it is important.

Because movies are often only drawing on one book at a time, or drawing on one run (or story arc) of a comic, important aspects may be lost. An example would be the Tim Burton or the Adam West takes on Batman versus the Christopher Nolan version. The latter drew upon more of the Batman comics than the earlier adaptations (not that either of those adaptations was bad*).

So while this doesn’t necessarily result in a direct adaptation, it does result in an adaptation that is faithful to the source material in the elements that matter.

*I’m pretending that the Joel Schumacher adaptations don’t exist. Akiva Goldsman is probably more to blame, given he has a long track record of making everything he is attached to that bit worse.

January 1, 2019

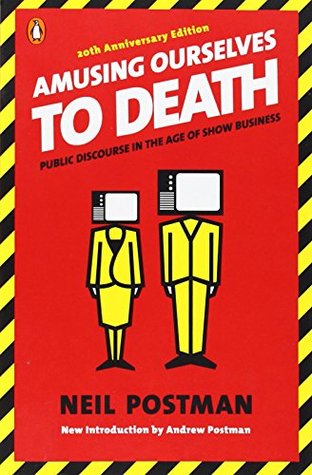

Book Review: Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business by Neil Postman

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business by Neil Postman

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

Being prophetic is really easy when you make a “kids these days” argument.

Amusing Ourselves to Death is Neil Postman’s ode to the “good old days” before television when entertainment wasn’t ruining everything. TV bad, reading good!

I decided to read this book after it once again started to be referenced as prophetic in the modern age. The first time someone mentioned this book to me I couldn’t help but feel the argument was likely to lack substance – you can amuse and inform at the same time.* What I found in this book was a supposition that isn’t without merit – slogans and sound bites can be influential whilst lacking any substance – but is argued in a cherry-picked and biased manner.

One example is how Postman claims that political campaigns used to be written long-form to influence voters, whereas now (meaning then in 1985, but many say it is highly relevant today) we get political messages in sound bites and 30-second adverts. This argument underpins his work and is at best convenient revisionism, at worst it is naive drivel. To suggest that there is no modern day long form political articles (and interviews, etc) is rubbish, just like the idea that the historical long-form articles he alludes to were well read by the masses is rubbish.

Another example is Postman claiming that media organisations aren’t trying to (in general) maliciously misinform their audience. We know that this isn’t the case. Even at the time this was written there were several satires addressing how “news” is deliberately framed for ratings (e.g. Network, Brave New World, the latter he references in the book). Either he has a different interpretation of malicious misinformation or he just thinks the media are incompetent.***

Now, his idea that we should be trying to educate kids to be able to navigate this new media landscape – instilling critical thinking, understanding of logic, rational thought, basic knowledge so that we are less likely to be fooled – is laudable. I completely agree. I’d also agree that there is a desperate need for this in people of all ages when we have an attention economy in place that is less interested in informing you than making sure your eyeballs stay glued for the next advert. I think this is why Postman’s book has resonated with people, the arguments aren’t without merit. But they are also deeply flawed and problematic.

I can’t really recommend this flawed book, but it isn’t without merit.

Interview with Postman:

* This modern review from an education professional sums up this point:

“Instead of striking a balance between the use and over-use of media in education, Postman has completely shut down the debate in the belief that there is no good way to use visual media like the television and film in education. If you take his thesis to its logical conclusion, the number of technological tools in the classroom would be reduced to the overhead projector, the ScanTron grading machine, the copier and the laser pointer, and the field of educational technology would be greatly reduced in the process.”**

** Read this review particularly carefully. The author cites a number of problematic sources for claims made, such as Ben Shapiro, David Barton, Glenn Beck, Jonathan Strong (of The Daily Caller). All are known to deliberately misrepresent their sources (e.g. see my review of Ben Shapiro’s book covering this issue).

***Hmmm, could be something to that argument. As I regularly say, don’t attribute to malicious intent that which could be incompetence.

NB: I don’t normally post reviews of books I haven’t enjoyed (3 stars or more out of 5). It is my intention that this particular review will be one of few exceptions.

December 30, 2018

Top 10 Posts of 2018

[image error]

Last year I wrote one of these “Top 10” lists discussing my year of blogging. I enjoyed it so much that I thought I’d do it again.

Let’s start with the stats. Because stats are awesome. Trust me.

I had a couple of goals for my blogging in 2018. I wanted to post more regularly and have more engagement (likes and comments) as I felt like there were periods in previous years when I’d not post for weeks at a time, and views weren’t translating to people liking and commenting. Wow, the last part of that sentence makes me sound needy… Anyway, I managed to write ~46,000 words in 135 posts, easily better than previous years, and reviewed 75 books. The consistent posting seemed to keep the month-to-month views more consistent than other years, with ~22k visitors and ~27k views (down a bit on last year). Likes and comments were the highest ever and more consistent per post with +600 likes and +250 comments.

Thank you to everyone for reading, following*, liking, and commenting this year. As I continue my writing efforts the views and interactions here keep me motivated.

1) The Actual 10 Most Deadly Animals In Australia

Once again reigning supreme. Originally written for one of those comedy list sites, I’m glad so many have enjoyed this post.

2) Do People In Australia Ride Kangaroos?

Second year in second place. One of my trademark snarky Quora answers. Its popularity both last year and this year shows that I need to write more articles about Australian animals.

3) Book vs Movie: The Bourne Identity – What’s the Difference?

This post was shared on a movie site and had a spike in views. I especially appreciated the belligerent commenters** who came to lecture me on all the points I could have included in a 10,000-word essay on the topic in my 400-word post.

4) Shark Attack

This is one of my older posts discussing the overblown coverage of shark attacks. I actually prefer the post I wrote a few years after this one, but probably need to revisit this topic with more recent stats. Which people can ignore in favour of the older post that pops up first in their search…

After watching Vin Diesel leap a souped-up V8 over a decidedly murky shark-filled estuary, I felt the need to write this post. I wrote another more recently summarising the series thus far. This will probably become a regular series given they have sequels, spinoffs, and a massive audience for years to come.

6) 20 Proven Benefits of Being An Avid Reader

Two places higher than last year, this article was a repost of a listicle, but unlike the original list, I’ve actually included links to references. Not that you’d know it since they have deleted the original.

7) Book vs Movie: Silence of the Lambs – What’s the Difference?

A post from last year that only seemed to find an audience this year. I’m not joking, literally 97% of the post’s views came this year. Another in my long-running series utilising the videos from CineFix.

8) 7 Types of Narrative Conflict by Mark Nichol

An older reblogged post that I added a few points to. I would actually like to write my own version of this to compile a number of posts I’ve made on this, such as 6 Story Arcs.

One of my art share posts. I do like sharing cool book-related pictures, cartoons, or comics. Hopefully, it gets more people to buy their stuff – hence the links I add to those sorts of posts.

10) Mythtaken: Shark Attack Deaths

Two shark posts in one list. It seems people are looking for shark attack statistics. Almost as if more people are going into shark territory and are surprised to discover sharks there. This post is 4 years old and some of the stats are 6 years old, so I should probably revisit this topic. Does anyone else hear an echo in this list?

Next year I’d like to see something from 2019 make the Top 10 for views. Two posts came close this year, but the perennial favourites keep attracting attention.

See you in 2019!

*I haven’t been keeping track of my follower numbers but know they have been steadily increasing in the last 2 years. I do appreciate the follows and everyone who ends up reading the posts on email instead of showing up in the site statistics.

**My commenting editorial policy precludes people thinking they can behave like they are on Twitter, Reddit, or Facebook, so you don’t have to see those posts.

December 28, 2018

New Year’s Resolutions For Writers

December 23, 2018

A Public Domain Festive Season Gift

It’s that time of year once more. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank all of you readers, followers, and friends for spending time with me and my random collections of (mostly book related) posts in 2018.

Before the New Year, I’ll post one of those Top 10 post lists to discuss the highlights of my 2018 blogging… and the stats, you know I love talking stats.

As a gift for this festive season, I wanted to share some free books with you all. You see, for the first time in over 20 years, on the first of January, books from 1923 will enter the US public domain.

Yes, it has been 75 years already… Wait, quick maths tells me that 1923+75=1998, so shouldn’t these books have already been available in 1999? Why, yes, yes they should have. But apparently, the US Congress decided that for totally justifiable reasons [insert eyeroll] that books from 1923 to 1977 needed an expanded copyright term of 95 years.*

I’ve blogged previously about how copyright has excluded a lot of titles from the public domain. This essentially made any out-of-print titles disappear. And academics like Rebecca Giblin have been researching how copyright needs to change.

But now (some of) the drought is over. Google Books will offer the full text of books from 1923, instead of showing only snippet views or authorized previews. The Internet Archive will add books to its online library, and stores will be able to make these titles available for cheap (studies have shown that public domain books are less expensive, available in more editions and formats, and more likely to be in print—see here, here, and here.)

A few examples of books that will now be available in the public domain:

Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan and the Golden Lion

Agatha Christie, The Murder on the Links

Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis

e.e. cummings, Tulips and Chimneys

Robert Frost, New Hampshire

Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet

Aldous Huxley, Antic Hay

D.H. Lawrence, Kangaroo

Bertrand and Dora Russell, The Prospects of Industrial Civilization

Carl Sandberg, Rootabaga Pigeons

Edith Wharton, A Son at the Front

P.G. Wodehouse, works including The Inimitable Jeeves and Leave it to Psmith (Source)

So have a happy holiday and enjoy whatever festivities you celebrate at this time of year with a free book!

[image error]

*See more on copyright from Rebecca Giblin’s Author’s Interest project.

December 20, 2018

Who Can You Trust? Unreliable Narrators

[image error]

The first rule of this month’s It’s Lit! is that you don’t talk about the narrator.

Unreliable narrators are an interesting topic. To some extent, I regard all narrators as flawed in some way. Unless you have omniscient narration you always have a limited viewpoint, and it could be argued that even with omniscient you still aren’t pulling away from the main narrative so it is limited as well. So I would argue that unreliable narrators are more a case of how unreliable are all narrators.

Who is the most powerful character in fiction? Villains may doom the world, heroes may save it, but no one has more control over the plot than the narrator – expositing the who, what, where, when and how directly into the reader’s mind. But how can you tell that the person telling you the story is telling you the whole story?

It’s Lit! is part of THE GREAT AMERICAN READ, a eight-part series that explores and celebrates the power of reading.

Hosted by Lindsay Ellis

December 18, 2018

Book Review: The Way of Zen by Alan Watts

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

When you sit, sit. When you browse Twitter, browse Twitter… Maybe there’s a reason social media causes stress.

The Way of Zen by Alan Watts is an introduction to Zen Buddism and its roots in Taoism and Mahayana Buddhism. It was one of the first books of its kind and tries to explain “Eastern” concepts to a “Western” audience.

After my forays into various “Western” philosophers and philosophies, I thought it was time to investigate some others that weren’t just footnotes to Plato. Having already read the Dao De Jing and a more modern guide to Zen, I thought reading a bit more on Zen would be interesting. Watts certainly covers some quite different ground to Zen in the Age of Anxiety and puts the Dao in more context.

This was certainly less of a philosophy text and more of an overview or introduction to Zen. One of Watts’ central aims was to make sure the reader understood how the “Western” philosophical tradition has a strict adherence to certain logical structures which the “Eastern” philosophies like Zen do not. This was certainly an important distinction and something that must have helped popularise Zen Buddhism outside of the “East”.

I will have to explore this topic further.

December 16, 2018

Book to Movie: Mary Poppins – What’s the Difference?

[image error]

This month’s What’s the Difference? from Cinefix looks at one of the movies that you probably only realised was based on a book when they made a film pointing that fact out: Mary Poppins.

Having not read the books, I don’t have much to say about this month’s What’s the Difference? I would like to segue into a topic that the recent Saving Mr Banks raised. I think there are some interesting points to be made about the differences between mediums when it comes to how and what is remembered.

Truly great books will generally be read by fewer people than the number who will watch a middling film adaptation. Make a great film from a great book and you will still reach more people with the film. I’ve previously mentioned how as many people saw the final Harry Potter movie as there were sales of all of the Harry Potter series of novels. So even if we just go on audience size alone, it is fair to say that a movie adaptation will shape people’s memory of an artwork.*

Of course, it is worth noting that the movie Saving Mr Banks is somewhat revisionist. Tad important to know this as large media companies dominate the landscape of society. I mean, next thing you know Americans will use movies to try and tell us they turned the war by capturing an Enigma machine…

This video essay by Lindsay Ellis talks about the Revisionist World of Disney:

*Further to this point is should this influence the author’s decision to allow a movie/TV adaptation knowing that their writing will take second place to the more popular medium?

December 13, 2018

What is the most satisfying genre of book for an author to write?

[image error]

I would posit that there are two things that are important to an author when writing with regards to the genre:

That the author enjoys the genre they are writing in;

That the genre suits the story they are writing.

I’d also argue that the first point is far more important than the second. I say this mainly because I want to provide a very superficial argument on the second point.

In a panel discussion entitled Bestsellers and Blockbusters on ABC TV’s Book Club, thriller author Matthew Reilly made mention of some literary authors who had been tempted to try writing thrillers – because money. Always about those big juicy bucks. Those authors didn’t really like the thriller genre and as a result, they didn’t understand how to write them and thus failed to write entertaining thrillers.

I have previously discussed one example of what Matthew raised in the above video. In 2014, the literary award-winning author Isabel Allende decided to dabble in crime fiction with Ripper. No, seriously, that was the title. Allende didn’t enjoy the experience. She was quoted as saying she hates crime fiction because:

It’s too gruesome, too violent, too dark; there’s no redemption there. And the characters are just awful. Bad people.

Allende went further to say that Ripper was a joke and ironic. The response to this was for crime genre fans to condemn her, bookstore Murder by the Book sent their orders back, and Goodreads ratings suggest it is one of her worst received books. Maybe next time she will not make those comments whilst on the promotional tour. Or, you know, not write something she doesn’t enjoy. One of the two.

Authors obviously have to invest a lot of time and energy in creating a novel. If they aren’t enjoying the experience, then that is likely to spill over into the quality of the end creation. So they are likely to invest time and energy in doing something they enjoy so that readers will enjoy it. Or try to grin and bear it as they go after some big juicy bucks.

The second point that authors consider is what genre suits the story they are trying to tell.* Genre can help define and shape the story. So the genre often acts as the stage or setting for the story. Think of science fiction and themes of social protest, or fantasy exploring social constructs, or horror exploring ways to dismember work colleagues. Obviously, some genres will be more suitable for telling certain stories.** As a result, the genre will be an important consideration in the writing process.

In summary, an author is likely to write in a genre they enjoy and utilise the genre that helps tell their story. To my mind, this is how an author thinks about the genre.

*Sometimes the opposite approach is used to give us a space western or sparkly vampires.

**Of course, shifting the usual themes and tropes from one genre to another can be a way to create stories as well. Where would we be without Firefly?

This post originally appeared on Quora.

December 11, 2018

Why it is (almost) impossible to teach creativity

Relishing the independence of the mind is the basis for naturally imaginative activity.

Relishing the independence of the mind is the basis for naturally imaginative activity.Shutterstock

Robert Nelson, Monash University

Industry and educators are agreed: the world needs creativity. There is interest in the field, lots of urging but remarkably little action. Everyone is a bit scared of what to do next. On the question of creativity and imagination, they are mostly uncreative and unimaginative.

Some of the paralysis arises because you can’t easily define creativity. It resists the measurement and strategies that we’re familiar with. Indisposed by the simultaneous vagueness and sublimity of creative processes, educators seek artificial ways to channel imaginative activity into templates that end up compromising the very creativity they celebrate.

For example, creativity is often reduced to problem-solving. To be sure, you need imagination to solve many curly problems and creativity is arguably part of what it takes. But problem-solving is far from the whole of creativity; and if you focus creative thinking uniquely on problems and solutions, you encourage a mechanistic view – all about scoping and then pinpointing the best fit among options.

It might be satisfying to create models for such analytical processes but they distort the natural, wayward flux of imaginative thinking. Often, it is not about solving a problem but seeing a problem that no one else has identified. Often, the point of departure is a personal wish for something to be true or worth arguing or capable of making a poetic splash, whereupon the mind goes into imaginative overdrive to develop a robust theory that has never been proposed before.

For teaching purposes, problems are an anxious place to cultivate creativity. If you think of anyone coming up with an idea — a new song, a witty way of denouncing a politician, a dance step, a joke — it isn’t necessarily about a problem but rather a blissful opportunity for the mind to exercise its autonomy, that magical power to concatenate images freely and to see within them a bristling expression of something intelligent.

New ideas are more about a blissful opportunity for the mind to exercise autonomy.

New ideas are more about a blissful opportunity for the mind to exercise autonomy.

shutterstock

That’s the motive behind what scholars now call “Big C Creativity”: i.e. your Bach or Darwin or Freud who comes up with a major original contribution to culture or science. But the same is true of everyday “small C creativity” that isn’t specifically problem-based.

Read more:

Creativity is a human quality that exists in every single one of us

Relishing the independence of the mind is the basis for naturally imaginative activity, like humour, repartee, a gestural impulse or theatrical intuition, a satire that extrapolates someone’s behaviour or produces a poignant character insight.

A dull taming

Our way of democratising creativity is not to see it in inherently imaginative spontaneity but to identify it with instrumental strategising. We tame creativity by making it dull. Our way of honing the faculty is by making it goal-oriented and compliant to a purpose that can be managed and assessed.

Alas, when we make creativity artificially responsible to a goal, we collapse it with prudent decision-making, whereupon it no longer transcends familiar frameworks toward an unknown fertility.

We pin creativity to logical intelligence as opposed to fantasy, that somewhat messy generation of figments out of whose chaos the mind can see a brilliant rhyme, a metaphor, a hilarious skip or roll of the shoulders, an outrageous pun, a thought about why peacocks have such a long tail, a reason why bread goes stale or an astonishing pattern in numbers arising from a formula.

We pin creativity to logical intelligence as opposed to fantasy.

We pin creativity to logical intelligence as opposed to fantasy.Shutterstock

Because creativity, in essence, is somewhat irresponsible, it isn’t easy to locate in a syllabus and impossible to teach in a culture of learning outcomes. Learning outcomes are statements of what the student will gain from the subject or unit that you’re teaching. Internationally and across the tertiary system, they take the form of: “On successful completion of this subject, you will be able to …” Everything that is taught should then support the outcomes and all assessment should allow the students to demonstrate that they have met them.

After a lengthy historical study, I have concluded that our contemporary education systematically trashes creativity and unwittingly punishes students for exercising their imagination. The structural basis for this passive hostility to the imagination is the grid of learning outcomes in alignment with delivery and assessment.

It might always be impossible to teach creativity but the least we can do for our students is make education a safe place for imagination. Our academies are a long way from that haven and I see little encouraging in the apologias for creativity that the literature now spawns.

My contention is that learning outcomes are only good for uncreative study. For education to cultivate creativity and imagination, we need to stop asking students anxiously to follow demonstrable proofs of learning for which imagination is a liability.

Robert Nelson, Associate Director Student Experience, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.