Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 406

September 8, 2014

new poetry book + book launch/reading,

My new poetry collection, If suppose we are a fragment (BuschekBooks, 2014) launches this month at the RailRoad Reading Series at Pressed Cafe, 750 Gladstone Avenue: 7:30pm, Thursday, September 25, 2014. I'll be reading alongside Ricardo Sternberg, and will have copies of the new poetry collection, as well as my brand-new collection of essays,

Notes and Dispatches: Essays

(Insomniac Press, 2014) and

The Uncertainty Principle: stories,

(Chaudiere Books, 2014). This is my second title with BuschekBooks, after

A (short) history of l.

(2011); enormous thanks to John Buschek for the ongoing support! Also: much thanks to Camille Martin and Cole Swensen for the generous back cover blurbs, and to Felix Berube for the use of his artwork on the cover. The cover artwork graces Stephen Brockwell's living room, where the bulk of the book was composed during the first few weeks of January 2011, as Christine and I did a house-sit or two over at his place [see the report I wrote on such at the time].

My new poetry collection, If suppose we are a fragment (BuschekBooks, 2014) launches this month at the RailRoad Reading Series at Pressed Cafe, 750 Gladstone Avenue: 7:30pm, Thursday, September 25, 2014. I'll be reading alongside Ricardo Sternberg, and will have copies of the new poetry collection, as well as my brand-new collection of essays,

Notes and Dispatches: Essays

(Insomniac Press, 2014) and

The Uncertainty Principle: stories,

(Chaudiere Books, 2014). This is my second title with BuschekBooks, after

A (short) history of l.

(2011); enormous thanks to John Buschek for the ongoing support! Also: much thanks to Camille Martin and Cole Swensen for the generous back cover blurbs, and to Felix Berube for the use of his artwork on the cover. The cover artwork graces Stephen Brockwell's living room, where the bulk of the book was composed during the first few weeks of January 2011, as Christine and I did a house-sit or two over at his place [see the report I wrote on such at the time].

Published on September 08, 2014 05:31

September 7, 2014

George Stanley, North of California St.

It’s pretty shittyliving in a Protestant city& my heart too bleak for self-pity

I sit in the Cecilsurrounded by a passelof loudmouth’d assholes

I swill beerto still my fearof the coming year

& there are mornings when I wake upso riddled with psychic breakupI can hardly hold on to my coffee cup.

I lived here three monthsin a house where I never onceheard anyone say please or thanks.

Not the best indoor weatherfor getting your head togetherbut it’s a personal matter. (from “Vancouver in April”)

“[A]ssembled from the contents of four earlier, out-of-print” poetry collections is Vancouver poet George Stanley’s impressive

North of California St.

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2014). Subtitled “Selected Poems 1975-1999,” the book is constructed from the bulk of four of his Canadian poetry titles: Opening Day: New and Selected Poems (Oolichan Books, 1983), Temporarily(Gorse-Tatlow, 1985),

Gentle Northern Summer

(New Star, 1995) and

At Andy’s

(New Star, 2000). For years, George Stanley has been known as one of a selection of arrivals into Canadian literature from the San Francisco Renaissance, as he, Stan Persky and Robin Blaser each headed north into Vancouver from a rich series of circles that included poets Jack Spicer, Robert Duncan and Joanne Kyger. It is well known that Stanley was a student of Jack Spicer, and it was through Spicer himself that Stanley’s first poetry collection, the chapbook The Love Root (San Francisco CA: White Rabbit, 1958), was published.

“[A]ssembled from the contents of four earlier, out-of-print” poetry collections is Vancouver poet George Stanley’s impressive

North of California St.

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2014). Subtitled “Selected Poems 1975-1999,” the book is constructed from the bulk of four of his Canadian poetry titles: Opening Day: New and Selected Poems (Oolichan Books, 1983), Temporarily(Gorse-Tatlow, 1985),

Gentle Northern Summer

(New Star, 1995) and

At Andy’s

(New Star, 2000). For years, George Stanley has been known as one of a selection of arrivals into Canadian literature from the San Francisco Renaissance, as he, Stan Persky and Robin Blaser each headed north into Vancouver from a rich series of circles that included poets Jack Spicer, Robert Duncan and Joanne Kyger. It is well known that Stanley was a student of Jack Spicer, and it was through Spicer himself that Stanley’s first poetry collection, the chapbook The Love Root (San Francisco CA: White Rabbit, 1958), was published. It seems clear that North of California St.works to articulate a period of Stanley’s work where his poetry really began to cohere, changed through his arrival north of the border and beginning to interact seriously with Canadian poetry and poets, including George Bowering, bpNichol, Fred Wah and Barry McKinnon. It is as though this is the first writing of Stanley’s to properly be situated in Canada; even as his poetic gaze occasionally shifted back to the city and country of his birth, it became more and more through the filter of Canadian influence. It is from this perspective that he begins to adapt his worldview, as he writes to open the poem “The Berlin Wall”: “Why, now that it’s breached, broken, does it cause / such consternation in me? // CBC brings me / the cries of happy youth, the singing, people / climbing up on the new meaningless Wall, / drinking champagne —[.]” Having been involved in poetry events via Warren Tallman in Vancouver for some time, Stanley moved first to Vancouver 1971, and the five hundred miles north in 1976 to Terrace, returning only to Vancouver some twenty further years later.

December. Coloured lights sketchhouses of family. Arms control descendslike a gift of Titans. Like little pre-Christian menimagined thor, or Russian serfsa good Tsar. Up where satellites crawl,Star Wars lasers, power’d by earth’s rivers, may streak.Today benevolence speaks, sublunary commanders

& we’ve never been so far from the stars,that were our friends. (“Terrace ‘87”)

Stanley’s work has always seemed comfortable in that space between the past and the present, and between geographies, even as he articulates his immediate present, including his discomfort of being in the air or travelling on the Sky Bus, between the cities of San Francisco, Vancouver, Kitsilano and Terrace. In her lengthy introduction to the collection, poet and critic Sharon Thesen describes Stanley’s “Aboutism,” writing that “Since his move back to Vancouver in 1993 to take a job at Capilano College (later University), Stanley has more than half seriously promulgated the poetics of ‘Aboutism’, his rebuttal to the excesses of the ‘language-centred’ excesses of the poetic avant garde […] which concerns itself with its unfolding context: ideas, thoughts, locales, occasions, persons, and words.” She continues:

Aboutism and transportation are natural companions, one enabling the other throughout North of California St. Stanley’s first book is entitled Pony Express Riders; his next-to-last, Vancouver: A Poem, was written while riding the bus between North Vancouver and his home in Kitsilano, a journey that involves crossing Burrard Inlet on the Sea Bus. To get to and from Terrace, along with “CBC brass” and timber executives, Stanley would fly nervously on small planes, some of them bush planes. The “Mountains & Air” lyric sequence is an Aboutist text from the point of view of someone encountering a terra incognita. Stanley’s airplane poems are almost always about mortality and fatality. Flight is a subject that creates opportunities for fear of the loss of “plain reality,” of losing touch with the earth, which Stanley likens to “the truth.” The sense of loss, inspired by flight, of the world, the person, the real, and the familiar, is not a backward-glancing nostalgia for a “golden” past, which we know, or are told we know, is a fiction; but rather derives from a sensed absence or emptiness in the present. In an essay about the late James Liddy, an Irish contemporary of Stanley’s who taught poetry in the Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Stanley notes that Liddy’s poems (much like his own, I would say) “open outward into the world, thus allowing the incarnate (opposite of virtual) object to be subject.” As in Stanley’s own work in this volume, “the real refuses to submit to the schema, the length of time in the line. Images come faster than they can be accommodated; the charge is to grasp the moment in its flight.”

As Thesen describes in her introduction, “Not so much a career retrospective as a retrospective reading of these four books,” the current volume sets aside earlier works more in keeping with an earlier apprenticeship, including not just that first title, but his Tete Rouge/ Pony Express Riders (White Rabbit Press, 1963), Flowers (White Rabbit Press, 1965), Beyond Love (San Francisco: Open Space, Dariel Press, 1968), You (Poems 1957 - 67) (New Star Books, 1974), The stick: Poems, 1969-73 (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1974) and Joy Is the Mother of All Virtue (Prince George BC: Caledonia Writing Series, 1977), as well as a variety of single-poem broadsides, including The Rescue (San Francisco Arts Festival, 1964). The word “apprenticeship” might be apt, but inadvertently suggests a dismissal of an enormous amount of activity, far more than what the current volume acknowledges. Stanley himself articulates the difference between that much earlier work and some of the work presented in this new volume in his“12 or 20 questions” interview, posted October 25, 2011 at Dooney’s Café:

My first chapbook (The Love Root, White Rabbit 1958) was ephemeral. Just a few pages of mostly pretentious verse – i don’t even have a copy of it any more. It was the second chapbook (Tete Rouge/Pony Express Riders, White Rabbit 1963) and the third (Flowers, White Rabbit 1965) that immediately gave me a readership in San Francisco and beyond, and were a mark of my recognition as a poet by the older poets (Jack Spicer and Robert Duncan), as well as by Joe Dunn and Graham Mackintosh, the principals in White Rabbit Press.

My most recent work (“After Desire” [The Capilano Review 3.14] ) is intensely personal. This marks a shift from much of the poetry I had been writing over the previous three decades, where my aim was to understand the world — in particular, how capitalism works, first in Terrace BC (“Gentle Northern Summer”), where being so new to the community I could see it more objectively, with less distortion than familiarity would have brought. Later I wrote poems (“San Francisco’s Gone”) to understand the history of the city and of my family, especially my parents, who were both born there.

North of California St., then, might argue for as much as a difference in approach as a difference in perspective. In her introduction, Thesen argues for a lack of larger attention throughout Canadian literature for Stanley’s work, something that seems to have eluded him, despite the length, breadth and bulk of his publishing which, frustratingly, can even be argued as an offshoot of the fact that Stanley lives in the western part of Canada. In spring 2011, Vancouver’s The Capilano Review produced “The George Stanley Issue” [see my review of such here], which featured critical and creative appreciations by a list of Canadian and American writers alike, including Michael Barnholden, Ken Belford, George Bowering, Rub Budde, Steve Collis, Jen Currin, Beverly Dahlen, Lisa Jarnot, Reg Johanson, Kevin Killian, Joanne Kyger, Barry McKinnon, Jenny Penberthy, Stan Persky, Meredith Quartermain, Sharon Thesen and Michael Turner, as well as an interview with Stanley, and a small selection of previously-unpublished poems. Publications that have been produced since the period North of California St. covers include the chapbook Seniors (Vancouver BC: Nomados, 2006), and trade collections Vancouver: A Poem (New Star, 2008) and After Desire (New Star, 2013), as well as the more than two hundred pages of A Tall Serious Girl: Selected Poems1957-2000 (Jamestown RI: Qua, 2003), edited by Kevin Davies and Larry Fagin. This collection, too, was created out of a frustration for Stanley’s lack of attention, as the editors of that American selected open their introduction:

This book has emerged partly from a certain frustration experienced by its editors. The Canada—U.S. border, though long and notoriously undefended, is real. When George Stanley (then age thirty-seven, but so youthful-looking that he was often mistaken for a draft dodger) crossed it in 1971, he all but disappeared from American literary surveillance. Though he maintained contact with his friends in northern California, and though more than a few Americans collected his limited-edition books and photocopied manuscripts, Stanley’s work has been, in effect, excluded from the canon of “vanguard” American poetry, and from the odd process by which the poems of a small percentage of poets become accessible in the wider world of classrooms and far-flung literary scenes. Though Stanley’s recent volumes, issued by Vancouver’s excellent New Star Books, are distributed south of the aforementioned border, too often, in our discussions with American poets young and old, we found mention of Stanley’s work met with near-total ignorance. Stanley had been inexplicably omitted from Donald M. Allen’s The New American Poetry (1960), and thus lacked the glamour of that association.

Published on September 07, 2014 05:31

September 6, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jane Munro

Jane Munro’s sixth poetry collection is

Blue Sonoma

(Brick Books, 2014). Her previous books include

Active Pass

(Pedlar Press, 2010), Point No Point (McClelland & Stewart, 2006) and

Grief Notes & Animal Dreams

(Brick Books, 1995). Her work has received the Bliss Carman Poetry Award, the Macmillan Prize for Poetry, been nominated for the Pat Lowther Award, and is included in

The Best Canadian Poetry 2013

. She is a member of the collaborative group Yoko’s Dogs (

http://yokosdogs.com/

) whose first book,

Whisk

, was published by Pedlar Press in 2013. She lives in Vancouver.

http://janemunro.com

Jane Munro’s sixth poetry collection is

Blue Sonoma

(Brick Books, 2014). Her previous books include

Active Pass

(Pedlar Press, 2010), Point No Point (McClelland & Stewart, 2006) and

Grief Notes & Animal Dreams

(Brick Books, 1995). Her work has received the Bliss Carman Poetry Award, the Macmillan Prize for Poetry, been nominated for the Pat Lowther Award, and is included in

The Best Canadian Poetry 2013

. She is a member of the collaborative group Yoko’s Dogs (

http://yokosdogs.com/

) whose first book,

Whisk

, was published by Pedlar Press in 2013. She lives in Vancouver.

http://janemunro.com

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Daughters came out a long time ago: in 1982. I still like that book, and it was well received – it even got short-listed for the Pat Lowther Award. However, I don’t think it changed my life. Maybe having a book published always changes one’s life somehow. But, at the time, I was a single mother with three young children and a job. Finding time to write was a challenge.

As for comparing my most recent work, Blue Sonoma (Brick Books, 2014), with the previous book -- I think it’s a progression in tone, content and style from Active Pass (Pedlar Press, 2010).

In tone and content, Blue Sonoma is a tougher, sharper, book. At its heart is a partner’s crossing into Alzheimer’s. While working on it, I realized that dementia could serve as a metaphor for the forgetfulness of society.

In style, its poems are open form, but there are ghosts of eastern “closed” forms of poetry. “Darkling” is a long poem composed of shorter ghazal-like poems. “Old Man Vacanas” are my adaptations of a 12th Century South Indian form.

By contrast, Active Pass explores connections among the visual arts, yogic discipline, and self-regeneration. It includes ghazals, loose sonnets, and open-form poems.

In both books, the witness’s journey is ghosted by her emotional and spiritual shadowboxing with her own life.

But there’s another way to answer your question. If you count Whisk by Yoko’s Dogs (Pedlar Press, 2013) as the previous book to Blue Sonoma, the contrast between books is even more pronounced. With Yoko’s Dogs (Mary di Michele, Susan Gillis, Jan Conn and Jane Munro), I'm writing collaboratively in the renga tradition. These linked verses eschew narrative and metaphor, both important in Blue Sonoma. And, Whisk is more playful than Blue Sonoma.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve always loved poetry. And, as I said earlier, by the time I started writing seriously, I had three young children. Composing a poem was more doable than writing in a longer form.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

All of the above! It has really varied. But, generally, writing comes slowly and most projects require many drafts.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Routinely, I’ve been a drafter of short pieces – I think of them as “protopoems” – and sometimes do one a day as a practice. They stay in my notebooks until I’ve forgotten about them. At some point, I go through the notes and pull out bits and pieces that catch my interest. I’ll type these up and slowly begin to work on poems. Gradually, a sense of the book will emerge and then I may work more deliberately on composing it and poems for it.

But this isn’t the only way poems begin for me. There are times when a poem, or even a sequence of poems, will just arrive. I’ve often found writing retreats very productive.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. They’re definitely part of my creative process.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Hopefully, the books themselves address the theoretical concerns behind their composition, as well as the questions I’m trying to answer in my work. Blue Sonoma is my most recent attempt to answer your questions.

I wouldn’t presume to speak for other writers about what the current questions might be for them.

That said, I don’t write in a vacuum. I read and listen and engage. I am now, and have been for a very long time, fascinated with the art and craft – the poetics – of what I’m doing, and what other writers are doing. I’m interested in the philosophical questions around writing. But these are huge topics!

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Jane Hirshfield says, “A good poem is a bit like a volcanic island. It creates new terrain for the soul.” In a volcano, the stuff coming up was previously hidden. Poems can make visible—and invite us to pay attention to—individual and social shadows. If Jung’s right and we need to agree to the whole experience to get a full life, then incorporating what was molten and unformed into a concentrated pattern of words gives us new ground—a place to explore, camp out, maybe even plant a garden. Oddly, though it may at first strike us as “new terrain,” we recognize and trust its reliability and its continuity with the rest of our experience: now that it’s there, it’s there.

I think this is also true about writing in other forms.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Who will ever read your work with more attention and engagement than a good editor? Having one is a great gift. Responding to an editor requires an equal level of attention and engagement from me, but that’s also a pleasure. I’m grateful for the pressure this process puts on the poems, and the way it makes weaknesses apparent. Then the question is, what to do about the issues raised.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Write as if you are already dead.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

This varies. Most days, I write. Some days, I spend many hours at the computer, but there’s also the rest of my life. Writing projects go through different stages. Some stages are more intensive and demanding than others. My days usually begin quietly. When possible, I like a rather meditative start.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Dreams. Reading. Walking. Yoga. Friends. Laughter. Art. I don’t know – whatever I feel I most need.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Now? Since I’ve moved back to Vancouver, I don’t have an immediate answer. But, during the twenty years I lived at Point No Point, once I got beyond Sooke, I could smell a change in the air. I woke up every morning to the fragrance of ocean and rain forest. Home was on the wild coast of the Island. It smelled fresh – air blown over waves across the Pacific, picking up the scent of lichen and spruce, cedar and hemlock, sword ferns, alder and moss.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Again, all the above: books for sure, but also nature, music, science, films, visual art. Even yoga: I’m going back to India again this fall to study yoga. And, silence – if you count that as a form: silence and dreams.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

This is another huge question. I read eclectically and pretty steadily. Lots of writers and writings are now – or have been – important for me personally and important to my work. I can’t begin to cite them all, not even the recent ones.

15- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Flamenco dancing?

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I might have been a visual artist.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Practicalities. I didn’t have time to both paint and to write. For many years, I had to put much of my energy into carrying on with the rest of my life. That’s not a complaint – but there were choices.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The Blue Fox by Sjón

Off the Map (2005) directed by Campbell Scott

19 - What are you currently working on?

A prose narrative and poetry with Yoko’s Dogs.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 06, 2014 05:31

September 5, 2014

rob mclennan interviewed by verbicide magazine

Nathaniel G. Moore was good enough to interview me recently around my collection of short stories,

The Uncertainty Principle: stories,

(Chaudiere Books, 2014), and the interview is now posted up at Verbicide magazine. Thanks much, Mr. Moore!

Nathaniel G. Moore was good enough to interview me recently around my collection of short stories,

The Uncertainty Principle: stories,

(Chaudiere Books, 2014), and the interview is now posted up at Verbicide magazine. Thanks much, Mr. Moore!

Published on September 05, 2014 05:31

September 4, 2014

Chaudiere Books indiegogo campaign: new perks by Bolster, McNair and The Complete William Hawkins!

There are less than two weeks left in the Chaudiere Books Indiegogo Campaign

, and we've added a whole slew of new perks! You can pick up two signed above/ground press chapbooks by Stephanie Bolster (including her out-of-print first solo publication, Three Bloody Words from 1996), a complete run of the long poem magazine STANZAS (1993-2006) [see the bibliography for such here], the possibility of having your own single-page letterpress broadside printed by Christine McNair, or even participation in her upcoming bookbinding workshop! Also, you can pick up copies of two works by Ottawa poet and musician William Hawkins, including Dancing Alone: Selected Poems 1960-1990 (Broken Jaw Press, 2005) and our newly-announced forthcoming critical selected, The Complete Poems of William Hawkins (Chaudiere Books: spring 2015), edited by Cameron Anstee! As well, there are still copies left of the documentary on John Newlove, signed works by Griffin Prize-winning poet David W. McFadden and a wide array of subscription packages for Chaudiere Books and above/ground press. We've already announced the publication of Chris Turnbull's Continua for 2015, but watch for an announcement soon for our other forthcoming titles!

There are less than two weeks left in the Chaudiere Books Indiegogo Campaign

, and we've added a whole slew of new perks! You can pick up two signed above/ground press chapbooks by Stephanie Bolster (including her out-of-print first solo publication, Three Bloody Words from 1996), a complete run of the long poem magazine STANZAS (1993-2006) [see the bibliography for such here], the possibility of having your own single-page letterpress broadside printed by Christine McNair, or even participation in her upcoming bookbinding workshop! Also, you can pick up copies of two works by Ottawa poet and musician William Hawkins, including Dancing Alone: Selected Poems 1960-1990 (Broken Jaw Press, 2005) and our newly-announced forthcoming critical selected, The Complete Poems of William Hawkins (Chaudiere Books: spring 2015), edited by Cameron Anstee! As well, there are still copies left of the documentary on John Newlove, signed works by Griffin Prize-winning poet David W. McFadden and a wide array of subscription packages for Chaudiere Books and above/ground press. We've already announced the publication of Chris Turnbull's Continua for 2015, but watch for an announcement soon for our other forthcoming titles!

Published on September 04, 2014 05:31

September 3, 2014

Ongoing notes: early September, 2014

Summer turns to fall, and we start thinking about fall events, including the ottawa small press book fair, which turns TWENTY YEARS OLD with our event on November 8. How can twenty years have already passed? Madness. And of course, watch for my double book launch on September 25th at RailRoad, as well as the launch of the three fall Chaudiere Books titles (by Roland Prevost, Amanda Earland Monty Reid) in October at the Ottawa International Writers Festival!

Summer turns to fall, and we start thinking about fall events, including the ottawa small press book fair, which turns TWENTY YEARS OLD with our event on November 8. How can twenty years have already passed? Madness. And of course, watch for my double book launch on September 25th at RailRoad, as well as the launch of the three fall Chaudiere Books titles (by Roland Prevost, Amanda Earland Monty Reid) in October at the Ottawa International Writers Festival!And Christine returns to work the same week as the small press fair, which means I’m home with baby Rose full-time. Will there be less of me here? Only time, I suppose, will know for sure.

Keep your eyes on the Chaudiere Books Indiegogo! It ends mid-month, and there are still plenty of amazing perks that have yet to be picked up. Christine McNair’s bookbinding workshop? An entire run of the long poem magazine STANZAS? The John Newlove documentary? And books, books, books…

Austin TX: I’m intrigued by the compact poems in Sarah Campbell’s new title, we used to be generals (Austin TX: further other book works, 2014). The author of Everything We Could Ask For (Little Red Leaves Press, 2010), the former Buffalo resident and editor/founder of P-QUEUE has collected some fifty short, sharp poems that turn and defy expectation, providing meditative twists and cognitive twirls.

WHEN WE WERE CHILDREN

Enough was never enoughHours, barbaric and bloomingThe hole of itAll that waiting around

There is the loveliest sense of smallness to these poems, carved pieces of wood and glass that Campbell has crafted over a long period, some composed with a remarkable smoothness, and others, with a deliberate rough quality. Some even have a flavour of the surreal to them, breaking any sense of expectation, turning the poem slightly on its side.

THE GREATEST OF ALL GREAT

We saw our plansWhere they would have beenHad we not been still living

Mt. Pleasant ON: poet and publisher Kemeny Babineau’s new offering is the chapbook A Poem of Days (2014). Produced as “A cycle of journal entries” from January 7, 2013 to January 15, 2014, and subtitled “(for Nelson and you” (with the Nelson referred to as poet and bookseller Nelson Ball), Babineau sketches out a series of short journal poem/entries that accumulate into the small space of a year, writing out his own version of the poetic “day book” done in the past by such as Gil McElroy, Robert Creeley and others.

What is

the social value in this

:

Solitary musings

made quietly public?

The poems are short, self-contained and sharp, yet each seem to lean into each other in sequence, suggesting the sketches were constructed very much as a loosely-formed suite. One day follows another, and the moments Babineau chooses to highlight are very much influenced by Ball’s own work, as Babineau moves through single points, the significant pause, and an engagement with nature.

Sky, penciled in

Then sun, a clean

White eraser

If such appeals, Cameron Anstee also reviewed Babineau’s chapbook over at his own blog, offering some extended insight into Babineau’s published ouvre.

Published on September 03, 2014 05:31

September 2, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Leah Horlick

Leah Horlick

is a writer and poet from Saskatoon. A 2012 Lambda Literary Fellow in Poetry, her writing has appeared in So To Speak, Canadian Dimension, GRAIN, Poetry is Dead, Plenitude,

Force Field: 75 Women Poets of British Columbia

, and on Autostraddle. Her first collection of poetry,

Riot Lung

(Thistledown Press, 2012) was shortlisted for a 2013 ReLit Award and a Saskatchewan Book Award, and a second collection, For Your Own Good, is scheduled for spring 2015 with Caitlin Press. She currently lives on unceded Coast Salish territories in Vancouver, where she co-curates the city’s only queer and anti-oppressive reading series.

Leah Horlick

is a writer and poet from Saskatoon. A 2012 Lambda Literary Fellow in Poetry, her writing has appeared in So To Speak, Canadian Dimension, GRAIN, Poetry is Dead, Plenitude,

Force Field: 75 Women Poets of British Columbia

, and on Autostraddle. Her first collection of poetry,

Riot Lung

(Thistledown Press, 2012) was shortlisted for a 2013 ReLit Award and a Saskatchewan Book Award, and a second collection, For Your Own Good, is scheduled for spring 2015 with Caitlin Press. She currently lives on unceded Coast Salish territories in Vancouver, where she co-curates the city’s only queer and anti-oppressive reading series.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? When Alison Roth Cooley and I made wreckoning, with JackPine Press, it was a process of learning to make a beautiful object and a collaborative work out of a beautiful friendship. We were so *in* each part of the process -- Alison made the ink, we soaked the paper by hand, and bound the books ourselves in her attic. Combined with the thrill of getting an ISBN and having a launch, it felt like we really had made the book. In a lot of ways, Riot Lung was felt very solitary and significant, and something about the object coming through the publisher felt like being taken seriously in a different way. I was so fortunate to have been supported by a network of many women reviewing the book -- in Room, in Arc, in Herizons, and on Autostraddle, and that was a gift in the recent climate of sexism and reviewing in Canada.

Looking back, the poems in Riot Lung are these little yard lights that say "I'm here, too! Look!" and to have those framed within a book was a real dream. My new work is much more about an emotional landscape, and trying to light that particular path.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? As a personality, I tend to really fixate -- on images, on sounds, on little chunks of narrative -- and poetry is my favourite way to recreate that fixation and share it as a moment on the page or in performance. I have a hard time creating enough of an arc to write fiction that would satisfy me as a reader, and as for nonfiction -- I need the mask of poetry as a genre because so much of my work draws on personal experience. In many ways, I feel like my poetry is a particular kind of nonfiction organized around stanzas and line breaks.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My process tends to shift -- I used to write very quickly and edit in a way that was more like playing Jenga -- what can I remove without the poem collapsing? After my MFA, I'm much more of a glacier. I read and re-read. Poems take a long time. Editing is about whittling things all the way down to the bones.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning? Riot Lung was very much a collection -- this little string of fires that had been sort of burning away since I was a kid. My most recent manuscript was the first time I'd played with narrative from the beginning. It was exhausting and I loved it. It was like there was another poem waiting behind each draft that I finished; little nesting dolls of poems.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? Readings are very much a part of my process. I have to read out loud to make sense of my drafts, and since so much of my writing is about being within and outside of communities. A lot of times I feel like the act of reading the poem out loud -- for audiences to see it as part of my body and out of my voice -- is just as much a part of the poem.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are? How do you make art that contributes to collective processes? What's worth salvaging from the canon? How do you create something beautiful out of trauma and grief?

Can we dream up something new while telling each other stories about the past? Is this any good?

7 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? "To tell is to resist."Wonderful quote -- it's the epigraph from a graphic novel called Killing Velasquez by Philippe Girard, though I can't remember the original speaker.

8 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? There needs to be walks and tea and a lot of time, a lot of reading, and not very much talking.

9 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? Esther McPhee, July Westhale, Zoe Whittall, Sara Peters, Dorothy Allison, Amber Dawn, Billeh Nickerson.

10 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? Other occupations I have attempted, almost all in support of writing: tour guide, juice barista, burlesque dancer, children's bookseller, retail doormat, and transcription monkey.

11 - What are you currently working on? Polishing up the manuscript I developed during my MFA. Co-organizing a reading series. Sunbathing. Tending to my emergent cat allergies. Living the dream.

12 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? Compulsion, adrenaline, introversion, and love.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 02, 2014 05:31

September 1, 2014

Phil Hall, The Small Nouns Crying Faith

96 pages, isbn 978-1-927040-58-4, $20Toronto ON: BookThug, 2013

96 pages, isbn 978-1-927040-58-4, $20Toronto ON: BookThug, 2013Through nearly a dozen trade poetry collections, Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall’s poems have the durability and devastation of koans, and the envy of poets who encounter them. Much like the books that preceded it, his eleventh trade poetry collection, The Small Nouns Crying Faith (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2013), is deeply immersed in the world and history, yet contained by neither. The Small Nouns Crying Faith borrows its title from the poem “Psalm” by George Oppen, himself known as a “poet of attentiveness,” a quality easily attributed to the more than three decades of Hall’s work. Oppen’s small poem, originally published as part of the collection This in Which (1965), opens with “In the small beauty of the forest / The wild deer bedding down— / That they are there!” with the fifth and final stanza, that reads: “The small nouns / Crying faith / In this in which the wild deer / Startle, and stare out.” Reading Oppen and Hall side by side, the comparisons run deep—Hall composes poems from his Ontario landscape, shades of his darker past, notes on his literary forebears (whom he refers to as his “heroes”), numerous artifacts, and could just as easily reference, at any point, the importance of pausing to listen for deer.

Genealogy

Our expedition followed her cold-tea stare

to chunks of boiled turnip wrapped in waxed paper in a lunch pail near camp that first night the shortest verse in the Bible

was recorded as her only expletive

*

Hectares from where her breast had proffered the warmed bottlewas found a cigarette rolling-machine wrapped in a clown costume

*

On our last out-bound day we came upon Royal Family clippings

attached to corn-stalks by bobby-pins all these items (photos/articles) we harvested & catalogued except the pins (rusted/discarded) note

little brown saw-marks in the corners of the stiff ceremonies

*

From Gab’s-Gift-Unsubstantiatedto Skugog Island an au pair …

Phil Hall has long been a poet of deep attention, compiling and collecting into an accumulation of poems that speak of artifacts and smallness, and a humanity rarely lived and articulated so well in Canadian poetry. This is his first trade collection since he won the Governor General’s Award for Poetry and the Trillium Award, aswell as being shortlisted for the Griffin Prize, for Kildeer (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2011), a collection of self-described “essay-poems,” published as part of BookThug’s “Department of Critical Thought.” Hall’s latest collection of what have evolved into “essay-poems” continue to practice a folk-local, examining the small, local and deeply specific, composing striking lines and phrases that accumulate into individual pieces, as well as sections of a far-broader canvas. Somehow, his lines manage to self-contain in such a way that even a shift in the order might still make the entire collection no less capable, breathtaking and wise. As he writes in the poem “Plum Hollow”: “The failure of order is the work / disorder is not the work.” The collection also includes a small pamphlet-as-insert, “Faith,” a poem-sequence composed up of words and phrases plucked from the book as a whole, selected and rearranged to reveal both something new, and something about the entire project.

I would celebrate every detail

now I have changed my thinking on that

no such thing as not being at seathe alphabet does not end or begin

wild yet this inextricable quickening

During the Ottawa book launch of The Small Nouns Crying Faith on June 2, 2013 as part of the AB Series, Hall suggested thatbeing left-handed, it was easier for him to read from the collection from back to front. There is such a great comfort to the work in The Small Nouns Crying Faith, one that knows the important answers might only emerge from important questions, and the level of self-awareness and self-questioning is remarkably rare and deep. If a pen falls in a forest, might anybody hear?

They hate me in that province to this day

& I them without reason once years ago I was judge for a book award

& didn’t pick the friend-to-all who was dying

it would have been right to give the prizeto that last-effort by that decent man

but in those days I was all about the workthe work

which is not a sacred thing which is not even a thing

but the tracings of a social pact almost accidental always incidental

grudges age backwards elixir to plonk

our vowels are slackened& the folios unaligned (“The Small Nouns Crying Faith”)

A version of the second of the book’s five sections, “A Rural Pen,”appeared as a limited-edition chapbook with Cameron Anstee’s Apt 9 Press in 2013, a series of (as the author self-described in his acknowledgements) “hacked scrawls,” lifting its title from William Blaketo write short and quick meditations with fireworks-momentum. What is continually astounding about Hall’s writing, via his last few poetry collections, is in the series of shifts, whether gradual or sudden, that bolt through the poems. Move your way backwards through his work to the award-winning Killdeer (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2011), to TheLittle Seamstress (Toronto ON: Pedlar Press, 2010) to White Porcupine (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2007) and everything that came previous, and you will begin to understand the differences in tone, mood and question. Urban explorations and a dark rural history have shifted entirely to an ease and sense of peace in a country setting, sketching poems and fences and birds. His recent collections have continued his interest in exploring and questioning through collaged-fragments of turned and twisted phrases, composed as poem-essays, but more recently the poems have shifted into poem-essays that explore the purpose, means and goals of the writing itself. Precision is an essential quality to Hall’s poetry, even as it discusses the impossibilities of such precision. The poems question, respond, reiterate and shift, as the hand that scrapes the rural pen moves throughout the world, working to ask exactly what the meaning precisely means, and if that is even possible.

It can’t be October

in the stove I burn old New Yorkers (but always save the William Steig covers)

lake light quavers leaning as it again mulls overthe smoke-darkened Rene de Braux painting

Chris benisoned walls with / now I get toa man / a cattle-gad on each shoulder half-way / no hurry / a Roman bridge(double arches / quick weed-hints)

a stuccoed villa set in along a hillsideAnn has taken the Wolf River apples down to Margaret 92 mornings I try to read page-shaped ash

a quote my fire preserves all night from columns it has only one use for now

riven by passion, not profit. We contin (“Claver”)

Hall’s isn’t a poetry carved into perfect diamond form, but a poetry whittled from scores of found material to be arranged, pulled apart and rearranged. The poems are important for what they know, what they ask and reveal, and they might tell you, if you know to listen.

[Originally appeared in Rain Taxi (Minneapolis MN), Volume 18, No. 3 (fall 2013): pp: 36-37]

Published on September 01, 2014 05:31

August 31, 2014

STANZAS magazine + Missing Jacket magazine: some above/ground press bibliographies

Lately I've been digging through boxes around our little house, given that the scattering of some twenty-plus years of activity are in the same location for the first time, and I've been discovering an enormous amount of material I simply forgot about. Part of this digging around prompted me to post a bibliography of two of the journals above/ground press has produced over the years:

STANZAS magazine

(forty-five issues between 1993 and 2006) and

Missing Jacket: writing & visual art

(five issues between 1996 and 1997). Not that much earlier, I posted a bibliography of the above/ground press "poem" handout as well, and one for

The Peter F. Yacht Club

; its slightly out-of-date, but an updated version of such exists in my new

Notes and Dispatches: Essays

(2014). Perhaps I should keep digging around, and possibly work on bibliographies for drop magazine, and various of the other odds and sods I've been involved in over the years...

Lately I've been digging through boxes around our little house, given that the scattering of some twenty-plus years of activity are in the same location for the first time, and I've been discovering an enormous amount of material I simply forgot about. Part of this digging around prompted me to post a bibliography of two of the journals above/ground press has produced over the years:

STANZAS magazine

(forty-five issues between 1993 and 2006) and

Missing Jacket: writing & visual art

(five issues between 1996 and 1997). Not that much earlier, I posted a bibliography of the above/ground press "poem" handout as well, and one for

The Peter F. Yacht Club

; its slightly out-of-date, but an updated version of such exists in my new

Notes and Dispatches: Essays

(2014). Perhaps I should keep digging around, and possibly work on bibliographies for drop magazine, and various of the other odds and sods I've been involved in over the years...

Published on August 31, 2014 05:31

August 30, 2014

Little Red Leaves Textile Series: Beverly Dahlen + Sara Lefsyk

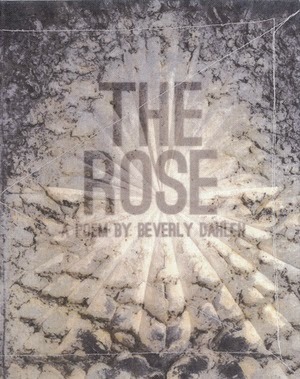

One of my favourite American chapbook presses, Little Red Leaves Textile Editionsare edited, designed and sewn by Houston, Texas poet Dawn Pendergast, with the covers for each title produced by materials found from a variety of sources. Over the past couple of years, I’ve written about her chapbooks here, among other posts. I keep hoping she might even answer the small press ’12 or 20 questions’ questionnaire at some point, possibly. First off: I like very much how the poem/chapbook of The Rose: A Poem by Beverly Dahlen (2013) is slowly pulled and stretched apart:

death rose

immortal rose

mortal rose

the stink of dying roses black at the heart

hedged edged etched each petal browning

failing falling

the invisible worm

San Francisco poet Beverly Dahlen’s second Little Red Leaves title—after

A Reading: Birds

(2011)—is, according to the website, “dedicated to Jay Defeo’s 2000 lb work with the same name.” The reference intrigues, and the internet explains that the late San Francisco visual artist Mary Joan Jay DeFeo (March 31, 1929 - November 11, 1989) was considered to be part of the Beat Generation, and “The Rose” (1958-66) is considered “her most well-known painting,” and one that “took almost eight years to complete and weighs more than one tonne.” Part of DeFeo’s piece is replicated on the cover of Dahlen’s small chapbook. Given the weight of the piece, the lightness of Dahlen’s poem is even more remarkable, able to articulate something of Defeo’s painting, writing “ghastly / ghostly / acid light,” to “sacred [sacrificial] star / dark star / im / ploded [.]” Furthering Dahlen’s ongoing series of response texts, “A Reading,” into the realm of responding to visual arts, I would be curious to hear some of the author’s thoughts on composing such a piece, if she would consider such a straight response, or something even akin to translation.

San Francisco poet Beverly Dahlen’s second Little Red Leaves title—after

A Reading: Birds

(2011)—is, according to the website, “dedicated to Jay Defeo’s 2000 lb work with the same name.” The reference intrigues, and the internet explains that the late San Francisco visual artist Mary Joan Jay DeFeo (March 31, 1929 - November 11, 1989) was considered to be part of the Beat Generation, and “The Rose” (1958-66) is considered “her most well-known painting,” and one that “took almost eight years to complete and weighs more than one tonne.” Part of DeFeo’s piece is replicated on the cover of Dahlen’s small chapbook. Given the weight of the piece, the lightness of Dahlen’s poem is even more remarkable, able to articulate something of Defeo’s painting, writing “ghastly / ghostly / acid light,” to “sacred [sacrificial] star / dark star / im / ploded [.]” Furthering Dahlen’s ongoing series of response texts, “A Reading,” into the realm of responding to visual arts, I would be curious to hear some of the author’s thoughts on composing such a piece, if she would consider such a straight response, or something even akin to translation.I TOLD THIS SMALL MAN: if I had a mule, a parachute and long flowing locks, I would jump out of this plane, put you in my shopping cart and push you clean to Brazil where we would change our names, cut our hair and join the local militia. After that, we would lead a small army of chickens to the sea and, after many days of floating, I would catch a small fish and name it Pavlov. Then, we would all jump into the sea and swim until we reached the large island of Europe, where we would start a mariachi band with my birth family and yours and the sun would set and we would all drink sugar water and go to sleep beneath a large curtain of black air.

Boulder, Colorado writer Sara Lefsyk’s second chapbook, after the christ hairnet fish library (Dancing Girl Press, 2013) is the utterly charming A SMALL MAN LOOKED AT ME(2014). Composed as a sequence of short prose sections, the design allows each paragraph/stanza to wrap over to the subsequent page, allowing for something far more compelling than had everything been standardized. It allows an interesting take on the prose, suggesting a more organic and linked progression from section to section. An imagistic sequence of self-contained pieces, each prose-section works to accumulate slowly into the realm of extremely short novella, heading towards a subtle and soft denouement. Where is this short work heading, exactly?

Published on August 30, 2014 05:31