Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 411

July 20, 2014

July 19, 2014

Renée Sarojini Saklikar, children of air india

Introduction

This is a work of the imagination.This is a work of fiction, weaving fact in with the fiction,merging subject-voice with object-voice, the “I” of the author,submerged, poet-persona: N—who loses her aunt and uncle in the bombing of an airplane: Air India Flight 182.

This is a sequence of elegies. This is an essay of fragments: a child’s battered shoe, a widow’s lament—

This is a lament for children, dead, and dead again in representation. Released.This is a series of transgressions: to name other people’s dead, to imagine them.This is a dirge for the world. This is a tall tale. This is saga, for a nation.This is about lies. This is about truth.

Another version of this introduction exists.It has been redacted.

And so opens Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar’s first poetry collection,

children of air india: un/authorized exhibits and interjections

(Gibsons BC: Nighwood Editions, 2013), recent winner of the 2014 Canadian Authors Association Award for Poetry.

children of air india: un/authorized exhibits and interjections

is an investigative book-length study into the facts and fractures of what has been referred to as “Canada’s worst mass murder”—the bombing of Air India Flight 182 on June 23, 1985 that killed 329 people, including 82 children. Working from a vast archive, from newspaper reports to personal stories, Saklikar’s investigation through the material left behind and generated by such an event to create a rich and complex tapestry of grief, absence, rage, incomprehension, compassion and all the internal and external systems that surrounded the trajedy, including the “Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182,” which wasn’t released until 2010, and the subsequent trial and acquittal of the accused: “there is not reconciliation. There is plausible and implausible. / Catastrophic and unreasonable, / Eighty-two children under the age of thirteen. There is time-consuming and / inconvenient. / There is manual and reasonably balanced. There are costs.” (“from the archive, the weight—”). Throughout the collection, poems exist as examinations of what remains, composed as a sequence of autopsies, archaeological studies, explorations and regret at such a loss of human life and potential, reported to and by the narrator, described only as “N”:

And so opens Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar’s first poetry collection,

children of air india: un/authorized exhibits and interjections

(Gibsons BC: Nighwood Editions, 2013), recent winner of the 2014 Canadian Authors Association Award for Poetry.

children of air india: un/authorized exhibits and interjections

is an investigative book-length study into the facts and fractures of what has been referred to as “Canada’s worst mass murder”—the bombing of Air India Flight 182 on June 23, 1985 that killed 329 people, including 82 children. Working from a vast archive, from newspaper reports to personal stories, Saklikar’s investigation through the material left behind and generated by such an event to create a rich and complex tapestry of grief, absence, rage, incomprehension, compassion and all the internal and external systems that surrounded the trajedy, including the “Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182,” which wasn’t released until 2010, and the subsequent trial and acquittal of the accused: “there is not reconciliation. There is plausible and implausible. / Catastrophic and unreasonable, / Eighty-two children under the age of thirteen. There is time-consuming and / inconvenient. / There is manual and reasonably balanced. There are costs.” (“from the archive, the weight—”). Throughout the collection, poems exist as examinations of what remains, composed as a sequence of autopsies, archaeological studies, explorations and regret at such a loss of human life and potential, reported to and by the narrator, described only as “N”:Informant to N: in the after-time

My name is [redacted] and my mother was [redacted].I was three months old when my mother died.I am without memory of my mother. I am not familiar with this record of events.June 23, 1985 and after.I get older. I am her only child.

For such a weighty subject matter, Saklikar’s thoughtful questioning works through language as much as it does through subject, managing a playful display of sound and shape, allowing form and function to ebb and flow, strike and slice as required. Saklikar’s book-length investigation of such a tragic event through poetry is reminiscent of other recent titles by Vancouver poets, including Jordan Abel’s The Place of Scraps (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2013) [see my review of such here], Cecily Nicholson’s From the Poplars (Talonbooks, 2014) [see my review of such here] and Mercedes Eng’s Mercenary English (Vancouver BC: CUE Books, 2013) [see my review of such here], each of which explore, engage and challenge a series of dark histories through various experimental poetic forms. As Saklikar writes in the poem “C-A-N-A-D-A: in the after-time, always, there is also the before…”: “each story-bit / a laceration / inside her deep down / secrets / dismembered / one limb after another— / incident as saga, saga as tragedy, / tragedy as occurrence / so what a plane explodes / so what people die, they die every day / in her body, blast and counter blast / (Air India Flight 182) / her story and the stories of other people / interact—a toxin?” As Saklikar, who lost an aunt and uncle in the attack, responded in a recent interview conducted by Daniel Zomparelli for Lemonhound: “My hope for children of air india, which by the way comes to me only now, after the fact of writing it, is that readers/listeners will view it as a site of query, of contemplation: what does it mean to lose someone to murder, on both a micro-level, that is, on a personal level, but also within a macro-context, within a public event.”

Testimony: her name was [redacted]

She was seven years old.Her mother said: she was full of life.Her mother said: she was very pretty.Her mother said: she loved to dance.Her mother said: she loved music.Her name was [redacted].She was seven years old.

Published on July 19, 2014 05:31

July 18, 2014

rob's (ongoing) editing service: poetry manuscript reading, editing, evaluation

For a few years now, I've been offering, to anyone interested, evaluation, editing and otherwise help with shaping a poetry manuscript for potential publication. I'd be thinking a series of back-and-forths, including notes, questions and revisions. $200 for a manuscript up to 100 pages, or $250 for up to 150 pages.

For a few years now, I've been offering, to anyone interested, evaluation, editing and otherwise help with shaping a poetry manuscript for potential publication. I'd be thinking a series of back-and-forths, including notes, questions and revisions. $200 for a manuscript up to 100 pages, or $250 for up to 150 pages.If you are interested, send me an email at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail (dot) com.

Published on July 18, 2014 05:31

July 17, 2014

The Capilano Review 3.23: Languages

1

WE LAYalready deep in the macchia, when youfinally edged into view.Nevertheless, we could notdarken out to you:ruled bylightduress.

2

WHO FOUGHT FOR YOU?The lark-figuredstone from the fallow.No tone, only that mortalbrightness carriedwithin.

The heightwhirls itselfout, more violently stillthan you. (“from Schwarzmaut (Blacktoll) by Paul Celan,” Mark Goldstein)

As Jenny Penberthy writes in the “Editor’s Note” for the new issue of The Capilano Review , the “Languages” issue (May 2014) is filled with “Multilingual poetry, ‘the clockwork discourse of Doctor Who,’ the language of invertebrates, the Red River Twang, Chiac, the language of the Psalms, html, and much more. An extraordinary variety of voices and languages is embedded in these pages, each piece a response to TCR’s call for ‘translations of new or old texts, re-translations, comparative translations, experimental translation, language/s behaving in unexpected ways, multilingual writing, older Englishes, mimicry, mis-translation, fumblings between languages, faux-translation, trans-translation, the ‘languages’ of different genres and the interplay between them.’” One of the most striking sections in the issue has to be by Christian Bök, another interplay on bpNichol’s infamous Translating Translating Apollinaire as “Translating Translating Apollinaire (Gallifreyan),” raising the bar on a piece that Darren Wershler once translated into Klingon. Through his sequence of circular visuals, Bök translates bpNichol’s piece into “the clockwork discourse” of Gallifrayan, the language of the Time Lords in Doctor Who. There are some other lovely interplays throughout the issue, some by writers emerging as some of our most challenging and engaged, from Jordan Abel to Oana Avasilichioaei to Liz Howard to Sarah Dowling, as well as more established poets such as Colin Browne, Nicole Brossard, Erín Moure, George Stanley, Rachel Zolf, Peter Culley, Steve McCaffery, Ted Byrne and Stephen Collis. Collis’ contribution to the issue is a translation of Empedocles' Fragment 17. As he includes in his short piece on the translation:

I began translating Empedocles when, after publishing too many books too quickly, I didn’t know what to write, and didn’t want to write anything really. Translation, especially the slowness of translating ancient Greek, seemed the ideal stop-gap—the ideal way of feeding my compulsion, while in some sense avoiding writing. A means of resistance. A brake. Empedocles had been an interest since I re-read the Presocratics while working on a book about change. That dialectic—it struck me as a dialectic—of Love and Strife, of attraction and repulsion, union and division, stuck with me. Everything now especially seems such a tug of war—the things I want to join, defend, and hold together—those things I want to resist, cut loose, disperse forever. To at once love and struggle against a humanity bent on the beauty of creation and the ugliness of destruction. To find these human attributes incommensurable and yet indissoluble. Walter Benjamin: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” How to resolve this? I fear we cannot.

Part of the appeal of The Capilano Reviewis how each issue works to engage with the visual arts as well as writing. Allyson Clay, who provided the cover art, has a sequence of paintings reproduced in the issue, “Groundsplatpink,” which she writes of to introduce her section: “My recent body of paintings, collectively titled Groundsplatpink (2013/14), stems from my longtime fascination with how paintings, particularly abstract paintings, are written about and described. Such descriptions are ubiquitous in art history texts and catalogue essays dealing with modern and contemporary painting. Books about painting tend to concentrate on surface treatments. (Interesting writing about painting can also be found occasionally in ‘how to’ books on painting.)” Really, there’s an enormous amount of worthy material in this issue, and far too much to write about in a single posting, from the synaesthesia works by Nyla Matuk, visual works by Margeaux Williamson, Michael Turner’s essay, “Text-based Public Art Works in Vancouver,” and Colin Browne’s exploration of Apollinaire’s Vancouver. Well known as being a translator as well as one of our finest poets and thinkers, Moure, for example, includes “A tale of a translation in process: François Turcot’s Mon dinosaur,” composing an essay as a sequence of journal entries:

I’m almost halfway through a first draft of Montrealer François Turcot’s fourth book of poems, a homage to a father, his father, and a co-presence with the final days of co-being with his father. And, après, a meditation on his absence. It is a Book of Hours, lost by the father and rewritten by the son. The book accompanies me eerily in these first months that follow my own father’s finale, in Edmonton.

Here, almost halfway: what does it mean to be almost halfway? Time’s membrane?

As well as a piece by Brossard, there are three translations of her works, by Amy Butcher, Karen Ocaña and Lary Timewell, who writes:

love cobbles its unreal span, a fragile aboveamong animals amongst words among doves

in the present continuous we wake, are awokenrepossessed of now as our own, the body s/urgesall possible plurality, ecstatic narrative ofthe continuum caresses, (each)tendril-exfoliate, (each) root of (each)worldknows this a confoundment / an exhuberance

babies boom all day, full-bodied from the hip, become‘boys & girls’ rolling out from (onto) flat tradition script

to be ‘just & fair’ in the ‘near & far’, lostrealms & sentiments & solitudes requirevertiginous words & animal names, energies given thatin dreams from genre & gender escape

Published on July 17, 2014 05:31

July 16, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with andrea bennett

andrea bennett's

debut book of poetry is

Canoodlers

(Nightwood, 2014), which follows the growth and class leaps of a townie tomboy from Hamilton, Ontario. andrea's writing has been published in magazines across North America, including Maisonneuve, Geist, and Grain, and her poetry has been anthologized in books from McGraw-Hill Ryerson and Ooligan Press. In 2013, her nonfiction received an honourable mention in the Politics and Public Interest category at the National Magazine Awards.

andrea bennett's

debut book of poetry is

Canoodlers

(Nightwood, 2014), which follows the growth and class leaps of a townie tomboy from Hamilton, Ontario. andrea's writing has been published in magazines across North America, including Maisonneuve, Geist, and Grain, and her poetry has been anthologized in books from McGraw-Hill Ryerson and Ooligan Press. In 2013, her nonfiction received an honourable mention in the Politics and Public Interest category at the National Magazine Awards.1 - How did your first book change your life?

Canoodlers is my first book. I'm not sure how much it has changed my life, yet -- I'm just stoked to have a book out in the world. I don't have any perspective on what that means, yet.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I do write fiction and non-fiction as well as poetry, actually, but I'll stick to poetry here: I like to write poetry because the speaker of the poem is always some iteration of myself -- usually some puffed-up Walt Whitman-y version, and it's freeing to live there for a moment.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It took about four years to write Canoodlers. Some of the poems appear in the book almost exactly as I wrote them on the day I wrote them, and others went through several drafts. Usually, when I write a poem, I've been thinking about a situation or a feeling for a little while, and then some concrete image or phrase drops out of the sky and I sit and write (or stand with my phone, keying into a draft email) as quickly as possible. Mean per poem draft one pen-in-hand time estimate: 17 minutes.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I've noticed that a lot of poets tend to choose a sort of poem-project for their second books, and it's tempting to do that, but I tend to write short pieces, yes, and figure out the cohesive part or narrative part later on. Though I do have a feeling I know what ground my second collection will cover.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like reading. I get very nervous beforehand, but once I'm on stage, in front of people, I like it up there. For me, it's a completely different skill-set than writing, or editing; it's not part of my creative process. My creative process happens beforehand, and then I have to summon up the nerve to inhabit the voice I've written on stage.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I studied English literature as part of my undergraduate degree, and I read a bunch of theory, and I still read some theory, but not so much. What I'm looking for as a reader and a human being is new insight and new perspectives; maybe these come from theory, and maybe they come from novels, or good conversation. (Here's a question, though: why on earth does psychoanalytic theory still have legs?)

If I'm concerned by theoretical anything when I'm writing, it's probably rhetorical strategies. I am fascinated with the way speech expresses interpersonal power dynamics, etc. I am also personally invested in documenting townie Hamiltonian speech patterns for posterity, because that is where I'm from.

The current questions? I think the questions for poetry are the same as the in-general questions. The political and social and cultural and religious questions. Also, formally, what comes next? And, how do I participate in conversations about Canadian poetries without picking a side?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don't think there is a given writer's role, necessarily. Some writers find themselves in a spot where they want to speak publicly, and they have the platform to do that. A traditional platform, I mean. And that has to do with talent and insightfulness and perseverance, but it also has to do with structural power and privilege. And then there are untraditional platforms, like Twitter or Tumblr and, well, just starting your own blog, and other talented, insightful writers find audiences there. Long story short: the role of a writer can be to research and write about issues of public concern. A writer can be a public figure.

Or, a writer can write poetry on their liveaboard in the Burrard harbour in Vancouver, and that can be their role: writing good poems from their small corner of the world.

Or, something in-between.

I would like to say that the role of a writer is to be on the side of justice, but lots of awful people write books. Like Rush Limbaugh. He even won a *Children's Book Award*, for goodness sakes.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I sincerely love working with good editors: they are your best readers. They push you to do better, and they see new things about your work, and they cut what needs to be cut.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I think the best thing that a writer can do is to celebrate their successes, really feel them. Buy a bottle of bubbly, and spend a day enjoying the hard work that has finally paid off, and find a couple supportive friends, and do whatever it is you do to personally celebrate. (Because I don't know about you, but I certainly let myself feel all the rejections.)

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I love writing nonfiction! Who knew? I never realized that I could choose to write the kinds of things I liked reading in Harper's and The Walrus and Maisonneuve. I wrote my first feature in 2011. It began as a project for a class I took at UBC. Now, nonfiction features are arguably my favourite things to write. I read a lot and I care about politics and culture and religion, and I have that maybe-I'm-an-awful-person attraction to exploring conflict and injustice. So that's the appeal for me, there.

Poetry is a compulsion, which is probably why it is my first genre. I'd write it even if no one read it or published it. I have no clue why.

Fiction is my weakest genre, and the hardest for me. Mostly because you really have to live inside a story to tell it, and it's hard to find the time to do that, and it's the genre where I miss my MFA workshops most acutely.

I don't consciously move between genres… when I have an idea for something new, it comes two by two with its genre.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have absolutely no routine whatsoever :/. Some days I will write for hours and feel obsessed with my subject and resent my day job. I tend to be a better writer when I'm earning my rent money as an editor -- it's like the writing gears are already well-lubed (not a gross metaphor at all). That is not currently the case, so I steal whatever time I can. (I so miss being a full-time editor. Can you imagine a better job? I can't.)

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

If I'm feeling sad and uncreative and I can't write, I do the brunt work that goes into researching and writing non-fiction instead -- access to information requests, database searches, interview transcriptions. To stop feeling sad and uncreative, I get some exercise in a place that has trees and/or ocean.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of cigarette smoke + my mother's perfume (Calvin Klein Eternity).

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Exercise: swimming, cycling, running. Being physically present in my body influences my work, and I liken various aspects of writing to various aspects of training for those things when I'm searching for metaphors.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Four writers: Kim Fu, Alice Munro, Ted Berrigan, Marilyn Hacker.

Four books: Michael Winter's The Death of Donna Whalen, Fred Wah's Diamond Grill, Margaret Atwood's Cat's Eye, Miriam Toew's A Complicated Kindness.

Four articles: Ted Conover's "The Way of All Flesh," Marci McDonald's "Stephen Harper and the Theocons," David Foster Wallace's "A Supposedly Really Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again," Lawrence Wright's "Paul Haggis vs. the Church of Scientology."

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Get married, live on a boat, have a kid, own a hammock, read in the hammock. Feel like I'm the best at something, even if it's just for a minute.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would probably have been a lawyer. I wrote the LSAT and everything, but lost my nerve. I figured that if I couldn't stomach the thought of the debt I'd take on to get the degree, then my heart wasn't really in it.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Books were the way I learned about people and the world when I was a kid. Writing was a natural extension -- I couldn't communicate with my peers in person at school, so I communicated with my imagined peers through writing.

But I had a bit of an unstable childhood, so honestly my world of occupational possibilities was not terribly wide at first, because I was petrified of taking risks, particularly economic risks. So I never thought I'd be a writer. I thought I'd work in communications, or whatever, but then I couldn't do that, I just couldn't, I had to get out and take the risk after all.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I came to Miriam Toew's A Complicated Kindness kind of late, just a few months ago, and I loved it. Out more recently, I think Tash Aw's Five Star Billionaire and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Americanah are both great books. I also recently (re)watched two great (but not new by any means) films: Errol Morris's The Fog of War, and Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm currently working on a piece about Mormon missionary experiences with Kim Fu ( kimfu.ca ), and another piece about the impacts of LNG development on communities in Northeastern BC. And a piece about heading to the Creation Science Museum in Alberta last summer at the precise time the southern part of the province was flooding. I've also been writing prose poems. Mostly about my partner, Will, and the particular but general strangeness of falling in love with someone.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 16, 2014 05:31

July 15, 2014

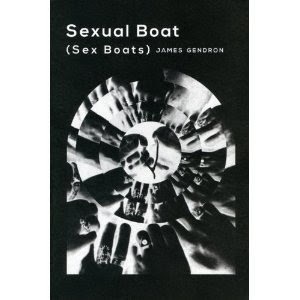

James Gendron, Sexual Boat (Sex Boats)

SEX BOAT

My open hands are innards.The one I hold toward youmasks a whole castlewhose gate/gatehouse

makes one evil.It makes our questions perfect.Like a gift, it ruins usgradually from inside.

Our true fate was dodged.Our fake fate was dodged.What could be left to us?

It’s never too lateto throw up.

Portland, Oregon poet James Gendron’s first trade poetry collection,

Sexual Boat (Sex Boats)

(Octopus Books, 2013), is constructed out of six sections of sassiness, sketchbook pieces, letters and sly talk in the form of short lyric poems. To be precise: five sections of short lyric poems, and one section, the fourth, made up of a sequence of lyric bursts. These are love poems caught up in longing, lust and sheer loneliness, aware of what has already been lost and just what else might be. Gendron’s pieces are composed nearly as train-of-thought explorations in lyric form. As he writes to open the fourth section, “IDEA”: “There are no ideas in death, just pain. It even hurts to take off my pants.” Whither the poem, James Gendron, for a poet who occasionally seems very pleased with the sound of his own voice. Very much in the vein of youth and the beginnings of real experience, these poems rattle and rail, clamour and clang about thoughtfully against the excess, embracing both light and the slow, steady dark.

Portland, Oregon poet James Gendron’s first trade poetry collection,

Sexual Boat (Sex Boats)

(Octopus Books, 2013), is constructed out of six sections of sassiness, sketchbook pieces, letters and sly talk in the form of short lyric poems. To be precise: five sections of short lyric poems, and one section, the fourth, made up of a sequence of lyric bursts. These are love poems caught up in longing, lust and sheer loneliness, aware of what has already been lost and just what else might be. Gendron’s pieces are composed nearly as train-of-thought explorations in lyric form. As he writes to open the fourth section, “IDEA”: “There are no ideas in death, just pain. It even hurts to take off my pants.” Whither the poem, James Gendron, for a poet who occasionally seems very pleased with the sound of his own voice. Very much in the vein of youth and the beginnings of real experience, these poems rattle and rail, clamour and clang about thoughtfully against the excess, embracing both light and the slow, steady dark.WASTING MY LIFE

Wasting my life in the gleaming snowaka cocaine. Did you realize the human bodyhas got over seven miles of braided thoughts?Under this girdle of fat I’m wasting away,in a sweater, eating from a bucket.In fat I see myself distilled more honestly than in my face.It stuffs me full of non-predestined life.

Pain: where do you come from?I feel you, because I’m emotional. And I feel youagain, because I’m remotional.

Published on July 15, 2014 05:31

July 14, 2014

Lisa Jarnot, a princess magic presto spell

My review of Lisa Jarnot's a princess magic presto spell (Solid Objects, 2014) is now online at The Small Press Book Review.

My review of Lisa Jarnot's a princess magic presto spell (Solid Objects, 2014) is now online at The Small Press Book Review.

Published on July 14, 2014 05:31

July 13, 2014

The Poetry of Phil Hall, selected with an introduction by rob mclennan (in-progress)

A few weeks ago, I signed the contract to edit a critical selected by poet Phil Hall, to appear as part of The Laurier Poetry Series published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Exciting, yes? Now, Phil and I are spending the next month or three working on a rough list of selections, before meeting up later in the fall to hammer out a final selection, and then on to our individual essays.

A few weeks ago, I signed the contract to edit a critical selected by poet Phil Hall, to appear as part of The Laurier Poetry Series published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Exciting, yes? Now, Phil and I are spending the next month or three working on a rough list of selections, before meeting up later in the fall to hammer out a final selection, and then on to our individual essays.Not that this is the first time I've worked on Phil Hall: see the essay I wrote on his work, or more recently, this review. Or, alternately, there was this (and of course, the short essay on such).

Phil and Ann were nice enough to have us out for lunch back in early May, which allowed he and I to discuss some of the considerations for how we might approach such a collection--although I suspect they really only invited us out so they could meet baby Rose (which we were both okay with).

Published on July 13, 2014 05:31

July 12, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joanne Arnott

Joanne Arnottis a Métis/mixed-blood writer, born in Winnipeg, Manitoba and based in Coast Salish territories on the West Coast. A publishing and performing poet since the 80s, and a blogger in more recent years, Joanne is mother to six young people, all born at home. An active participant in many online and in-world collaborating groups of writers, she is a mentor and piecework editor, an essayist, as well as a poet and activist.

Joanne Arnottis a Métis/mixed-blood writer, born in Winnipeg, Manitoba and based in Coast Salish territories on the West Coast. A publishing and performing poet since the 80s, and a blogger in more recent years, Joanne is mother to six young people, all born at home. An active participant in many online and in-world collaborating groups of writers, she is a mentor and piecework editor, an essayist, as well as a poet and activist. Arnott is a founding member of the Aboriginal Writers Collective West Coast, The Aunties Collective and Transcultural Academy (an international writers’ collective centered in Africa). She has served on The Writers Union of Canada National Council (2009), The Writers Trust of Canada Authors Committee, and as jury member for the Governor General's Awards/Poetry (2011). Halfling Spring: an internet romance (Kegedonce Press) is Joanne’s ninth book, and her sixth book of poetry.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book changed my life quite a bit: I dreamt of it! I was paralyzingly shy and deeply opinionated, so, having a book in the world meant that the world might ask me for my presence or opinion, which smoothed the path dramatically. I received the offer to publish as a result of showing my manuscript to a teacher on the other side of the country, so, it was miraculous, too, having a publisher phone up and say, “please?” This same publishing deity asked for my next book (before I’d conceived of one), and the next… that was a very solid footing that arrived as manna from heaven. (Thank you, Barb Kuhne!)My most recent work is far less fussy. I do not spend three years moving commas around, I publish sooner. I am of course twenty years older, but, there is a strengthening loop that happens between poet and world. Two decades in the biz has done a great deal for both my self-confidence, and my ability to hold a pen lightly.2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I started with fiction and poetry. My eldest sister studied at University of Windsor, when I was in high school, and she invited me in to many circles of poets, both the undergrads who soon became dependent on sherry and the professionals who spent hours debating what to name a gathering of poets, over many diverse cups, which thenceforth failed to gather (naming is all). I came away with the indelible impression that poetry is cool, far cooler than all other genres, and conducted myself accordingly. Just before high school I lived in rural Manitoba, in a house with few books, and so the books we did have loomed large in impact. One of these was a hefty compendium of best-loved English language poems, so that formed an excellent tutorial base, a wide gathering of voices all with distinct landscapes and rhythms. 3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Sometimes very long incubation, avoidance, endless raw writing that veers this way and that before I find the straightforward path: this is generally true of essays. Sometimes fruits dropping fully formed from my pen, all I need is to keep a basket nearby, and gather the harvest: this is generally true of poetry. Some poems become herculean wrestling matches, some poems want to be essays, and so, long processes of reconciling the bits until we have something that is polished and coherent. Going through the basket of poems to decide what to send to a magazine, or what to put where in a manuscript, is a pleasure and work too. Often it reveals patchy bits that require another polish, or new revelations that might be explored more fully.

Working with an editor is good, it helps a poet to recognize one’s own secret codes, as opposed to metaphors that speak to the beyond-me audience. This was most important in the early days, but even now each new manuscript reveals a few such items, and so I spell it out or say it different, or I teach my editor how to see things the way I do.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I am definitely a piecework operator, creating many unique pieces that I then combine into larger scrolls. I do intend to write a book that has been pre-sold, at some point, and do the whole query and pitch route: this chapter will cover that territory, etc. Sometimes a poem will arise with its title, and proclaim to be a book, in which case I do my best to accommodate.

Halfling spring is such a poem. It is based on a specific Anishnabe story, and rose out of a yearlong exploration of mermaid tales. Once written, it had the feeling of putting its finger precisely on the pulse of the whole flock of poems that I was writing. So that became the title of the book of love poems.

A Night for the Lady arose out of a similar stream—the poem articulating researches of the frame story from Arabian nights, on the one hand, and mermaid tales (a shorter poem with the same name) on the other. The former worked as a gathering-in poem, but not for the same collection as Halfling spring, so, the conversations with the world poems were gathered under this title, a kaleidoscopic gathering.

Halfling spring is much more focussed, strictly I and Thou.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings are essential to my process. I come out of an oral tradition, the Metis and the Irish as they came together in southern Manitoba, the French and the Scots. This may sound very important, but it is in fact very casual: sing! Talk! Around the time I started to move into book form, I read an interview with Maria Campbell, she admonished writers not to leave our work in the drawer. The work is not complete until it has been given to—or given back to-- the world.

I am very much an energy sort of person, so, I need to test my work aloud with an embodied audience, and read the energy exchange that happens, before putting the final burnish to the work. There is no way of substituting the idea of a poem for a real poem in action. Without experiencing my poem within a human gathering, without that palpable sense and visceral call and response, it is incomplete for me.

I do love to perform. There is a reciprocity different in the experience of textual exchange, though I have to admit, I do love textual swap formats too.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Yes. I am receiving, synthesizing, and returning energy to the world, as part of a collective living-breathing-balancing. I combine a syncretic approach and deep motivation. Ethics and aspirations are a part of it: Neal McLeod’s anthology, Indigenous Poetics, includes my essay, “small birds: songs out of silence,” and I delve the specifics there more deeply.

For myself, when I gaze across the wide range of poetries in Canada specifically, and poetry streams globally, I think the most pressing questions and challenges are around wholeness, a sense of collective integrity. Can we make space for all communities and poetics, all traditions of oratory and literary values of elegance, or will hell-bent for fragmentation flavours be a final chapter, privileging the urban over the traditional, secular over sacred, text and thought over voice and embodiment, etc.?

For me, whatever the genre, song is the most important value in the written word. It is a joy to listen to embodied oratory, and a pleasure to follow the lead of an excellent authorial voice through hundreds of pages.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The world is unfolding every moment. We are a part of that. There is the whole production of capital, ‘the people have a write to make a living.’ Those of us with the freedom of speech may feel an obligation to put it to good use, to pick up the pen for purposes of ‘witnessing.’

What I find most exciting is the work being done in the interface between oral and text, and between one language and literature and another, these cross-fertilizations. Canada has a huge volume of work that has not been fully integrated into our collective sense of CanPo, so, these are exciting times to be alive and at work.

Like it or not, the writer in Canada today is a public intellectual. Others will look to you for leadership and guidance. Wherever I am, whatever I am doing, I try to remain aware of the way that the world relies upon me, to make sense, as best I can.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I enjoy working with a good editor, and I have worked with many: only rarely did I find it quite baffling/unhelpful, a small handful of challenges. At the same time, I have met writers whose work was sidelined for decades, because a teacher or editor was indelicate and inappropriately matched: so, it’s a good question. For me it isn’t essential, my work is essentially completed before the editing begins, but, nonetheless clarifications en route to text publication is a normal part of the business.

I think the core revelation about editors is that the author has the final word: you are expected to negotiate, this is a great opportunity to learn and to teach, and the process isn’t something to be afraid of. If you feel the editor is not leading you where you want to go, and you feel you cannot communicate in a reciprocal way, you may be well advised to find a new placement for your work.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Don’t worry about me. Worry about your own self”

One of my pre-schoolers attempting to derail my editorial interventions: an awareness of roles and boundaries is always fruitful. I try not to obsess about things beyond my control, and to do well by everything that crosses my desk.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

Well, I am inherently a culture critic, it is simply how I was raised: I have listened to long monologues on the inappropriateness of cars, extreme excavations on religions and how they might be organized better, deep analyses on how the world works and how it “shouldn’t.” Polemics were part and parcel of surviving to adulthood. It is a family gift. Likewise, whatever I start off to write, becomes memoir/autobiography to some degree, that is somewhat reflexive, an inner bent or proclivity.

I love writing essays, I always have. What has been a challenge for me internally is, defining authorities—who has the right to make comment on what aspect of reality? I have published a book of talks and essays (Breasting the Waves, 1995), and have enough work to publish another: I went into hiatus after the first collection was published, ten years passed before I started writing essays again.

In recent years I have tended toward writing more about literature, still with a memoir or colloquial flavour, and less poetic perhaps so the thoughts will register as thoughts, ideas, and not simply as music. I became curious about the whole realm of secondary literature, and began to create that, too, as a less onerous form of literary production. The transit from wallflower to raconteur is an ongoing thing.

I have a strong interest in structures, and while that is expressed more in political or volunteer realms, it is certainly a part of my mind that is engaged in writing nonfiction and poetry, how to identify and bridge gaps, how to point out and smooth impediments, etc.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write every day, generally beginning in the email box and moving into deadline work, unless I am in a certain mood, at which time I will avoid the responsive-writing and focus inward, often starting in my journal and moving into word processing as the work progresses.

I love to sleep, to dream, and to wake. If I wake with a dream, I move first to the journal, before anything else.

If I don’t bounce awake, I may hit the alarm many times, to squeeze as much sleep and half-sleep as possible out of my day. Then I put on the kettle (a whistling kettle), call the kids for school, and commence.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

If I am uncomfortable, needing to communicate with no words coming, I turn to images, doodling in my journal or running image searches online. I do a lot of my processing laterally, so, making and sending illustrated letters, or adding a pictorial element to an essay or an interview, or a flock of poems I have found online. Researching friends and sending them pdf versions of themselves.

Another way to answer this question: sometimes I think of body tension and an inability to focus or settle into things as an accumulation of stories, a muscular glut of some sort. The process becomes one of identifying which stories I need to tell to which audience— may be a co-worker, may be a loved one, may be the world. I can tell what I need to say only by locating the correct alignment, and I feel myself substantially relaxing as the stories spill.

For deepest refreshment, I have to spend hours out of doors, along the rivers, the sea, among the grasses or trees.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Sage is a scent that goes right through me, setting me at ease. Dried grass, snow, old pipe or cigarette tobacco scents, fragrance of coffee, slow cooking meats. The scents of snow and of rain, a rain-fresh street.

[Related disclosure: I am allergic to many perfumes and chemical scents, so I find myself moving away from people wearing scented products, however much I may want to stay and converse.]

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

McFadden is not wholly correct: scrolls, inscriptions, architecture, oratory and song have all transformed into and inspired many books, more than we can count.

I have some impatience with books that reference only books, and thoughts that reference only other thoughts and thinkers: the nexus of embodied realms and the ancients with the breaking wave of the new, that’s a beautiful playground. Nature, music, fabric, visual art, people: science too. Excellent seascapes and geographies and cosmos/mologies.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Some of that I’ve touched upon already in recent interviews, long lists of influencers, teachers, fellow travellers; rafts of neo-pen pal correspondents, cascades of conversation of a textual nature.

I have a raft of indigenous writers with whom I keep in touch, AWCWC, old lady hunting and Storytellersplayspace, the conversational groups are a bit quiet these days, but the co-nourishing and the real world mutual supports carry on. Whether the e-group developed after real world gatherings or as an independent manifestation, it is essential for me to keep an inner balance, by keeping the roots watered and feeling (noticing) the sun through the trees.

I have been learning about Persian poetry through correspondence with poets, particularly Mahmud Kianush (UK), and about African literature more generally through collaboration and conversation with many different writers in a group headed by Ugandan poet-activist Beverley Nambozo and Zimbabwean novelist-filmmaker Tsitsi Darembenga (Transcultural Academy). A few other mixed writer e-groups, Canadian poets, and I’ve just met many new-to-me west coast writers via the Cascadia Poetry Festival, expanding the real world roster, following up with blog visits, research, reading, further conversations.

I have been taking part in a Reconciliation Through Poetry project via SFU/Centre for Dialogue, in honour of Chief Robert Joseph. One of the poets is also in the TA group, and another in AWCWC, so in some respects this is the current balance point.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Celebrate my birthday (in December) with a beach party (on a hot summer day)Pursue scholarly research in an academic (as opposed to a freestyle poetic) manner

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

My favourite jobs have been in print shops, there is something that I love about towering stacks of paper, different qualities and kinds of paper and print communications. Also, I love fabrics, making fabric would be a fine explorative alternative to what I do now, and selling these in the marketplace.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

In a family of artists, there is a certain amount of jockeying for space, for finding one’s own form within a spillingly creative productive environment. As fifth-born of nine, the best singers, visual artists, scientists, writers, performers had all been identified, the smartest, the most beautiful, the most charming, etc.

In the end, it comes down to what I can do quietly, without telegraphing to the world the insubordination of what I am producing. Of course, that only covers the moments of production, so, I have had to toughen up, to speak for myself (albeit clutching pieces of paper), and to learn to stand my ground. Letting the nascent orator out into light of day.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last two films I’ve most enjoyed are Detective Dee and the Phantom Flame, and The Way: each has a greatness in depth and richness of associations, cultural resonances.

The question of greatness among books is sending me down endless corridors of contemplation, touching on the functions of memory, the management of time, the years when I lay in my bed with banks of books around me, the more recent ages of work-dominated readings, books in manuscript print-out form and books in the process of creation. Amongst all of this wealth, can I bring one bright title into focus, and offer up its name?

20 - What are you currently working on?

Just diving into reading some three-hundred poems by writers of Africa, of which I may shortlist just fifteen. Then I will read thirty poems shortlisted by other judges, Richard Aliand Kgafela Magogodi, and they will read my fifteen, and we will engage in a process of choosing among the forty-five poem shortlist the winning poems of this year’s BN Poetry Award. BNPAhas been for five years an award for emerging woman poets of Uganda, and this is the first year when the contest is open to men as well as to women, and to African writers internationally.

TA blog: http://transculturalprojects.wordpress.com/

My blog: http://joannearnott.blogspot.ca/

Researching and writing about my family’s religious roots and routes, and about to receive some further skills development in relation to editing, with a specific focus on indigenous authors.

Tonight: AWCWC collective supper at Native Ed College to celebrate Jordan Abel’s BC Book Prize (Poetry), for The Place of Scraps

12or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 12, 2014 05:31

July 11, 2014

Touch the Donkey supplement: new interviews with McElroy, Martin, McCarthy + Baus

Anticipating next week's release of the second issue of

Touch the Donkey

(a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with first issue contributors Gil McElroy, Camille Martin, Pattie McCarthy and Eric Baus?

Anticipating next week's release of the second issue of

Touch the Donkey

(a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with first issue contributors Gil McElroy, Camille Martin, Pattie McCarthy and Eric Baus?Also: there's a new self-profile, "On starting a new poetry journal," newly posted over at Open Book: Ontario.

The second issue features new writing by Julie Carr, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Pearl Pirie, David Peter Clark, Susan Holbrook, Phil Hall and Robert Swereda. And, once the new issue appears, watch the blog over the subsequent weeks for interviews with a variety of the issue's contributors!

And of course, copies of the first issue are still available, with new writing by Camille Martin, Eric Baus, Hailey Higdon, rob mclennan, Norma Cole, Elizabeth Robinson, Rachel Moritz, Gil McElroy and Pattie McCarthy.

Really, why not subscribe?

The journal now even has its own Facebook group. How is it possible to resist?

Published on July 11, 2014 05:31