Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 402

October 18, 2014

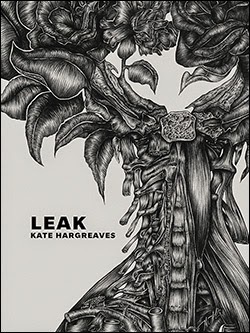

Kate Hargreaves, Leak

SPLINTER

Windsor splints me. Splints shins—feet bat-battering asphalt cracks thud thud thwack thwack thwack thwack shoelace plastic tip clipping concrete. thfooooo—exhale fast against damp armpit air. Pause one foot on pavement, other shoe rolling over ants and grass and woodchips two feet from dog shit sizzle in the haze. thhoooo—exhale re-tie loop over around and through, tie the ears together and tap toe towards sneaker end. Stand. Sweat slips between vertebrae, over spine juts like waterfall rocks—slish slide slim. On feet and level with horse heads over sparse hedge over-pruned by ninety-five degree weeks and days, nights of dry roots, brown branches, crisp. Rind warming in racer-back lines, heat-dying Friday afternoon onto shoulders arms and calves. Out and back: laterals around perambulator pushers and camera couples pausing to snap the elephant and her babies. thfoooooo—thfoooooooo—hard breaths in time with glitter on the wet streets calves and quads suck blood and O2 from head spinning and concrete clumps cling to clay soles. Windsor sticks to my sneakers, sod, cement, gum, cast-iron eggs and birds catch on my laces. thfooooooo—exhale, and scuff rubber on road, to scrape off stones, cedar chips, Tim Horton’s cups and spare change. Shin splints. Cable-knit air chokes my out-breath. thf—bronze base casts over my shoes. Drags me toward river railings and drills toes into sod. Headphones pumping dance dance dance till your dead at path-side. Playlist over. Riverside runner: artist unknown. Bronze, textile and sports tape. Splint into the soil.

Windsor, Ontario poet Kate Hargreaves’ first trade poetry collection,

Leak

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2014), is striking for the sounds she generates, allowing the language to roll and toss and spin in a fantastic display of gymnastic aural play so strong one can’t help but hear the words leap off the page. Utilizing repetition, a variety of rhythms and homonyms, Hargreaves’ poems mine the relationship between language and the body, and rush and bounce like water through seven suite-sections: “Heap,” “Chew,” “Skim,” “Pore,” “Chip,” and “Peel.” As she writes to open the poem “HIP TO BE SQUARE”: “Her hips sink ships. Her hips just don’t swing. Her hips fit snugly in skinny jeans. Her calves won’t squeeze in. Her hips check.” She manages to make the clumsy, awkward and graceful tweaks and movements of the body into an entirely physical act of language, bouncing across the page as a rich sequence of gestures. Given the fact that she also published a collection of short fiction,

Talking Derby: Stories from a Life on Eight Wheels

(Windsor ON: Black Moss Press, 2012), “a collection of prose vignettes inspired by women’s flat-track roller derby,” this writer and roller derby skater’s ability to articulate text in such an inspired and physical way shouldn’t be entirely unexpected, but the fact that it is done so well is something of a marvel.

Windsor, Ontario poet Kate Hargreaves’ first trade poetry collection,

Leak

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2014), is striking for the sounds she generates, allowing the language to roll and toss and spin in a fantastic display of gymnastic aural play so strong one can’t help but hear the words leap off the page. Utilizing repetition, a variety of rhythms and homonyms, Hargreaves’ poems mine the relationship between language and the body, and rush and bounce like water through seven suite-sections: “Heap,” “Chew,” “Skim,” “Pore,” “Chip,” and “Peel.” As she writes to open the poem “HIP TO BE SQUARE”: “Her hips sink ships. Her hips just don’t swing. Her hips fit snugly in skinny jeans. Her calves won’t squeeze in. Her hips check.” She manages to make the clumsy, awkward and graceful tweaks and movements of the body into an entirely physical act of language, bouncing across the page as a rich sequence of gestures. Given the fact that she also published a collection of short fiction,

Talking Derby: Stories from a Life on Eight Wheels

(Windsor ON: Black Moss Press, 2012), “a collection of prose vignettes inspired by women’s flat-track roller derby,” this writer and roller derby skater’s ability to articulate text in such an inspired and physical way shouldn’t be entirely unexpected, but the fact that it is done so well is something of a marvel.PORE

She pores.She pores over her psychology textbook.She pores over the late-night pita menu.She pours water over tea steeps and pours.She pore-reduces. She scours.She scrubs.She pores over her blackheads in the mirror.She skins.She skins her ankle with a dollar-store pink plastic razor.She nicks.She grazes.She snacks at half-hour intervals throughout the day: trail-mix, dried cranberries, arugula, celery.She scans the fridge for leftover spinach.She pours olive oil and vinegar on lima bean salad.She pours oil on troubled waters.She waters the daffodils.She never rains.She showers.She buzzes her head.She hums.She drones.She counts. She sorts.She: out of sorts.She’s out on a limb.She limps.She wilts.She droops.She drips coffee on the floor.She sips.She slips on wet tiles.She sinks.

Published on October 18, 2014 05:31

October 17, 2014

'Poet pushes together fragments in new book'

I had a little article on my Ottawa book launch for If suppose we are a fragment (BuschekBooks) in Carleton University's weekly paper, The Charletan, recently.

I had a little article on my Ottawa book launch for If suppose we are a fragment (BuschekBooks) in Carleton University's weekly paper, The Charletan, recently.For the sake of full disclosure, I include the text of the little interview the writer of the article, Phelisha Cassup, conducted with me, via email:

1. How did you chose the title? What inspired it? Is there any specific moment or story that it was derived from?

I’m not completely sure where the title of If suppose we are a fragment originated. It sounded good when rolled off the tongue, and on the page as well. Given that it was composed during a very early period in my relationship with my now-wife, the poet Christine McNair, one might make speculations on the nature of the fragment, and how relationships are about pieces slowly fitting together into each other.

2. What advice do you have to aspiring writers/journalists?

Just write. To aspire means nothing until you do.

Also, read as much and as widely as possible. Edits and revision are essential, but only after the first draft. Be fearless, but never reckless. Listen to the parts of you that aren’t often acknowledged. Be open to ideas that might not make sense at first, or at all to anyone else. And be patient: any craft takes years and some thousands of hours to perfect. You don’t have to solve it all in one day, or even one year.

3. Do you have any current projects on the go?

Multiple. I’m currently attempting to complete a manuscript of short stories, as well as a poetry collection. I’m also editing a selected poems by the Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall, who is currently writer-in-residence at the University of Ottawa.

4. What was the hardest part of creating this work?

After twenty-plus years of writing full time, the work ethic is there, the patience is there, and the attention is there. The hardest part? Often, the hardest part is attempting to find a home for completed manuscripts. Publishing has shifted over the past decade or so, away from taking chances on riskier works and seriously reducing the possibilities for sales across the country (the reduction in bookstores and reviewing meaning fewer books are receiving any attention at all). It is making it hard for a great many of us to find publishers.

5. Is it hard to balance family, your new baby (Congrats again!!), with writing?

Thanks much! Balance is always a tricky thing, whether considering relationships, employment, schooling or anything else. This past year has been an enormous shift, certainly, going from full days of work to half-days, trading time with Christine until her maternity leave ends. Once she goes back to work, I’ll be attempting to carve writing spaces over the next few years around the occasional childcare, the uncertainty of naps and my own exhaustion.

6. What makes this piece unique from others?

Itself.

7. Where can your works be purchased?

I’ve a number of works available for online sale at https://alllitup.ca , and most of my publishers each have websites where one can purchase books. Failing that, one can simply visit my table at the semi-annual Ottawa small press book fair in November. The twentieth anniversary edition of the fair occurs on Saturday, November 8, 2014 on the second floor of the Jack Purcell Community Centre on Elgin Street. Otherwise, one can always send me an email at rob_mclennan@hotmail.com and we can do something more directly.

8. Any other things you want the students of Carleton to know/ read?

The In/Words Reading Series, run through Carleton University’s In/Words Magazine and Press, is perhaps the most fun reading series currently in town. For information on any and all Ottawa literary information, including readings, book fairs, calls for submissions and other such notices, one should constantly be paying attention to www.bywords.ca

Published on October 17, 2014 05:31

October 16, 2014

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Amanda McCormick on Ink Press

Ink Press Productions letterpress prints books, broadsides, and other art. We hand-make journals and other paper goods out of found materials. Our main goal stems from the human need to create. IPP was founded by Amanda McCormick, with close help from Tracy Dimond and Juliannah Harrison.

Ink Press Productions letterpress prints books, broadsides, and other art. We hand-make journals and other paper goods out of found materials. Our main goal stems from the human need to create. IPP was founded by Amanda McCormick, with close help from Tracy Dimond and Juliannah Harrison. inkpressproductions.com

1 – When did Ink Press first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?

Ink Press began with espresso ink , a literary journal I founded in 2009. When I moved to Baltimore in 2012, I met Tracy Dimond who founded a writing workshop called Gin & Ink. We bonded over our vision for art with community.

In 2012 we decided to partner to create, Ink Press Productions: a multi-leveled project committed to building community and delivering affordable-handmade art to the public.

Together we have learned that the most limited resource we have is time.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?

When I was younger, I wanted to be a journalist so I became the editor of my high school newspaper, Paw Print. Since then, I have consistently been involved in the printing & distribution of books. I have come to want to know what books can be rather than try to prescribe what they are.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?

Engage in the collective dialogue by supporting each other and DON’T be boring!

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?

We’re not boring—haha jk. There are a lot of great independent presses out there doing amazing things. I can’t pin down what makes us different—maybe it is that we are operated by Tracy Dimond & Amanda McCormick? There are no other versions of us in the world.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new chapbooks out into the world?

There are so many ways to get books out into the world. The first one and maybe most important is to do it! Make it happen and don’t consider your limitations. Everyone has limitations just like everyone has abilities. As a publisher I was lucky to find a collection of people who are interested in me and my artistic vision. Likewise, they have their own artistic goals. I realize how important it is for people to cooperate in life and art. In that way, I’d say the best way to get a book out into the world is to plant an idea and let it grown with the people around you & find more seeds: make the process fun and meaningful and build it in an environment that is generous and grateful.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?

The type of editor I am depends a lot on the situation. Sometimes I like to dig deep and work close with the write and their work. Other times, like in the case of the chapbook contest, I am looking for something that leaves me speechless (in a good way).

7 – How do your books and broadsides get distributed? What are your usual print runs?

We mostly distribute hand-to-hand at readings or events or through Internet sales. We do not have a set number of books to print but we are interested in the exclusivity of smaller runs. Having limited resources plays into how we create but we welcome that challenge.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?

Tracy and I both work very intricately on most projects. We also have regular input from other artists, our friends in Baltimore. Plus, our publishing process is in collaboration with the writer. There are great benefits to publishing handmade books as a team—in fact, I could and would not want to do it if I didn’t have the people I have to do it with. It challenges me to compromise but that is not a drawback.

9– How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?

Being a publisher has changed the way I view my own writing in the same way that the my daily activities influence my writing—I can hardly remember a time I was interested in writing without also being interested in book-making and publishing. From that, the benefit of working closely with other talented and ambitious writers is that they inspire me and I get to take that inspiration to my own writing and art.

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?

I am totally for DIY publishing! It is empowering and gives you a freedom to do as you please with your work. We’ve published my chapbook and Tracy’s book, but we also love opportunities we have to work with other writers. We didn’t publish either of our books for the sake of publishing, but rather because they were strong conceptual projects that we wanted total creative control over. Unlike anything, I see DIY publishing as a conceptual gesture to move away from the institutionalization of art: it is important for artists to know that they aren’t obligated to be legitimized through an establishment. That said, I also think it is important to connect with other people that you admire in independent publishing and putting my writing in the hands of another publisher is a great way to do that. Yes! Publish my book! Submitting work to another press is a way to say “I care enough about what you are doing to trust my writing with you.”

11– How do you see Ink Press evolving?

It is hard to see how Ink Press Productions will evolve even in the coming year. I feel all we can do at this point, with our resources, is keep it up and do our best to work toward a sustainable future.

I would like to see IPP become an organization that supports art and provides a source of security for people devoted to a life of creating.

12– What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?

As a publisher, the thing I am most proud of accomplishing is the connections I have built with others artists of similar missions. Of course I am proud of our books and the events that we hold, but all of those things are nothing without the people involved.

Time is the most frustrating resource. Tracy and I both have jobs and are going to school, so we’re very careful to not overload our publishing schedule. We have big plans to build up Ink Press Productions, but we have to acquire capital and credibility in order to grow.

14– How does Ink Press work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Ink Press in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?

Hmmm, this is a tough question. I feel like everything we do is an attempt to engage with the literary community, both immediate and extended. We use our artistic gestures to be a part of a conversation centered in many of the things I’ve already been talking about. I suppose the most direct connects we have are through the project-based collaborations we do with other presses. For example, this past spring we partnered with sunnyoutside press to put on an event producing the “2-Hour Chapbook” for the Buffalo Small Press Fair. Currently, we are working with jmww to create a handmade edition of their chapbook contest winner. This fall, we are partnering with EMP, a local arts collective, to build a workshop series focused on writing and handmade books.

15– Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?

We try to have a launch event for every book we publish. We like to celebrate our accomplishments! In addition, we do a number of readings and events. We are interested in exploring how we can create something innovative and artistic in a space for the public to be involved. We want people to be proud of what they create, so we strive to add it to a public. So yes, any public event is important for the press.

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?

We use the Internet for sales and promotions. We’re still trying to navigate the internet side – handmade art encourages someone to feel it’s body. The internet works best for visual and audio work, but we have been able to stay connected with people through the internet.

17– Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?

We only open submissions for particular projects. Otherwise, we publish books mostly through solicitation of writers we know and admire. When someone approaches us directly, we will always consider their work. We ask that they email us the project.

18– Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.

I’m Just Happy To Be Here by Mark Cugini: We met Mark a few years ago. He asked if we would consider his manuscript. After he emailed it to us, we knew we wanted it. His poems are a poetry party in a Staten Island duplex, but they are also full of sincerity. He strikes a beautiful balance.

Work Ethic by Tim Paggi: We are in the MFA in Creative Writing & Publishing Arts program at the University of Baltimore with Tim. Both of us loved his writing from the first workshop we had together, so we talked about soliciting a chapbook from him. The discussion of despair and hope, through neon and food imagery, drew us in. We felt we could make a beautiful book with him and were overjoyed that he agreed before his manuscript was even finished.

espresso ink V : A literary anthology on CD. This was a really fun project because it was something that we never attempted before and it involved so many people. We took some of our ideas about community and performance and combined them into a handmade / letterpressed CD and ‘lyric book.’

12 or 20 (small press) questions;

Published on October 16, 2014 05:31

October 15, 2014

above/ground press: 2015 subscriptions now available!

Twenty-one years and counting. Can you believe it? There's been a ton of activity over the past year around

above/ground press

, from the rebuilding of

Chaudiere Books

(the trade extension, one might say, of above/ground) to the founding of the poetry journal

Touch the Donkey

(included as part of the above/ground press subscription!). Just what else might happen? Current and forthcoming items include works by Kate Schapira, Gil McElroy, Jennifer Baker, Gregory Betts, Stephen Brockwell and Kemeny Babineau (2014) and Elizabeth Robinson (2015), as well as a whole slew of publications that haven't even been decided on yet.

Twenty-one years and counting. Can you believe it? There's been a ton of activity over the past year around

above/ground press

, from the rebuilding of

Chaudiere Books

(the trade extension, one might say, of above/ground) to the founding of the poetry journal

Touch the Donkey

(included as part of the above/ground press subscription!). Just what else might happen? Current and forthcoming items include works by Kate Schapira, Gil McElroy, Jennifer Baker, Gregory Betts, Stephen Brockwell and Kemeny Babineau (2014) and Elizabeth Robinson (2015), as well as a whole slew of publications that haven't even been decided on yet.2015 annual subscriptions are now available: $50 (in the United States, $50 US; $80 international) for everything above/ground press makes from now until the end of 2015, including chapbooks , broadsheets , The Peter F. Yacht Club and Touch the Donkey (have you been keeping track of the array of interviews posted to the site?).

Anyone who subscribes before November 1st will also receive the last above/ground press package (or two) of 2014, including those exciting new titles by derek beaulieu, Kate Schapira, Jennifer Baker, Kemeny Babineau, Gregory Betts and Gil McElroy (plus whatever else the press happens to produce before the turn of the new year).

Why wait? You can either send a cheque (payable to rob mclennan) to 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1H 7M9, or utilize whichever paypal button that applies to you:

Canadian subscriptions:

American subscriptions:

International subscriptions:

And keep checking notices for The Factory Reading Series . There’s so much more to come.

Published on October 15, 2014 05:31

October 14, 2014

The Examined Space, by rob mclennan : Ottawa Magazine,

I had a back-page piece in the September issue of Ottawa Magazine, solicited by Dayanti Karunaratne, that I am extremely happy with, on Centretown, history and neighbourhoods. In case you didn’t happen to see such on newsstands, I reprint (with permission) here:

I had a back-page piece in the September issue of Ottawa Magazine, solicited by Dayanti Karunaratne, that I am extremely happy with, on Centretown, history and neighbourhoods. In case you didn’t happen to see such on newsstands, I reprint (with permission) here:Ottawa Journal |by rob mclennanThe Examined Space

I’ve lived in Ottawa long enough to appreciate the layers that exist in the city, and long enough to become bored with the repeated self-designation of sleepy government town. One has to know where to look. Perhaps during such a period of urban development is the best time to re-think a self-portrait. The unexamined space, one might paraphrase, ain’t worth living in.

The bulk of my twenty-five years — in some half-dozen houses — have been in Centretown, and I’ve long been aware of the former lots granted to Colonel John By and William Stewart, which were part of the central core of what was once a Victorian town of lumber and rail. Before that, this was the site of some hundreds of years of native settlement, exploration, and travel. Montreal Road, for example, is quite literally the road to Montreal, and lies on the trails First Nations peoples established as they travelled back and forth between what wasn’t yet Ottawa to what wasn’t yet Montreal.

To live in any space or landscape, one should at least make some attempt to understanding it, both as a current entity and a historical one. There were the riots that regularly began between Irish Shiners and French in Bytown throughout the early part of the 19th Century, culminating in the infamous Stoney Monday Riot of 1849. For their own safety, the police wouldn’t interfere with most of these fights until they began to threaten the more expensive neighbourhoods further east beyond Lowertown. Imagine: in 1845, we were the most dangerous city in the Commonwealth. From these events, we remember Joseph Monferrand, who later became known as Big Joe Mufferaw, the legendary hulk of a man waist-deep in a number of those battles.

The bulk of Centretown is the former Lot F, picked up by Colonel By in 1834, with the southern stretch picked up by William Stewart, where he and his wife eventually created Stewarton, with streets his wife Catherine named for their children: Ann (later renamed Gladstone), Catherine, McLeod, and Isabella. To understand a space is to understand what it has come through. There is the used bookstore at Bank and Frank streets that housed a punk club beneath, back in the 1970s. There is the former theatre still known as Barrymore’s that every so often someone inquires about, wondering why someone doesn’t clean up the outside. Confederation poet Archibald Lampman once lived on Florence Street with his mother. Elvis performed at the Auditorium on Argyle Street, the same stadium that once housed the Ottawa Senators — it was later demolished and replaced with the YM-YWCA.

There are more recent events as well. The collapse of the wasted space that occupies Bank and Somerset streets, at the husk of the Duke of Somerset building, for example. Imagine: someone with money could refurbish such as an Ottawa version of Toronto’s Gladstone Hotel, providing much-needed hotel space downtown, a martini bar and a cool arts space.

At the corner of Bank and Argyle streets, there was the crossbow murder of crown attorney Patricia Allen by her husband in 1991. There are events we remember because we need to remember them.

The shifts are constant, continuous, and to be expected. Condos arise like mushrooms, including around McLeod and Bank, within the former village of Stewarton. Recently, we discovered that the house we lived in, just west of the intersection, was once owned by a friend’s great-grandparents. He sent wedding portraits from the 1920s of his grandparents as they stood in our driveway. Ottawa poet, songwriter, and cabdriver William Hawkins claimed to know the house in the 1970s as a very sketchy rooming house, as he delivered various unsavory types to a front door we would grace for two years. The house itself, with our enviable third-storey turret, was one of the first on our block, constructed in 1895. That stretch of McLeod sits on such a ripple of bedrock that basements become, from house to house, of a completely random depth.

Some might resist the construction of condos in the city’s core, but it far beats the alternative. Most of the 1990s seemed to include every second or third business closing, and it felt as though the plan was to actually exclude downtown residents. I feared for Ottawa turning its downtown into a dead core, much like what Calgary had been for a long time. The revitalization, done properly, can provide new energy to a city that requires both renewal and the knowledge of what had come before.

And, as Saskatchewan poet and Chinatown resident John Newlove once wrote, the past is a foreign country. And yet, so much is familiar. He lived on Rochester Street for 17 years, the longest he lived anywhere. Arriving from British Columbia in 1986, he once claimed to live in Ottawa, “for his sins.”

A recent postcard-sized story of mine reads: “Every city constructed out of a series of markers, of landmarks, but what happens to a city when it is constantly in danger of losing? What happens to memory when a city is constantly new? There is nothing to hold on to, there are no regulars to keep the rent in your restaurant. There is no heart, no soul, no loyalty. When a city is constantly new, it runs the risk of losing all meaning.”

This knowledge provides a richness to the landscape. Part of why we resisted the condo-company attempting “South Central” was precisely for the sake of our own history. We don’t need a new name. We already have one.

Ottawa-born rob mclennan is the author of, among others, The Uncertainty Principle: stories, the non-fiction Ottawa: The Unknown City, and the poetry collection If suppose we are a fragment. He blogs at robmclennan.blogspot.com

Published on October 14, 2014 05:31

October 13, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ella Zeltserman

Ella Zeltserman

is a Soviet-born poet living in Edmonton, Canada, where she is an active member of the local poetry community. Her poetry has been published in a number of anthologies and magazines. Her first poetry collection is

Small Things Left Behind

.

Ella Zeltserman

is a Soviet-born poet living in Edmonton, Canada, where she is an active member of the local poetry community. Her poetry has been published in a number of anthologies and magazines. Her first poetry collection is

Small Things Left Behind

.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Small Things Left Behind is my first poetry collection. I am not sure publishing it changed my life, but the process of writing the book did. I had these images, emotions and family stories inside me for a long, long time. Being finally able to put them into verse and onto paper felt very liberating. I have a sense of accomplishment as if I finally did something I meant to do for a while.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry is the most natural form of expression for me. I grew up reading poetry. From Pushkin’s fairy tales read to me by my mother to Akhmatova’s and Brodsky’s poems that I read throughout my life on an almost daily basis. Even my attempts at prose come too poetic, with images dominating the text.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The first draft of a poem comes very fast (or not at all). But the final version takes time. I often put the poem aside for it to settle; it may take a day or a year for the “final” version to take shape, there are no hard rules. Some poems come to a final version almost the same as how they are first written. Others end up different to the point of being unrecognizable. Some insignificant thought or image ends up being “the poem.” Again, no hard rules.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The poems can come from anything: a sound I hear, a smell that triggers some memories, some visual images. In Akhmatova’s words: “if you only knew /from what kind of trash the verses grow/ without any shame”.

Small Things Left Behind was written mostly in 2008-2009. I did not sit down to write a book. It was a very productive writing period and after a while it became obvious that there was a major theme developing. I put the collection together in 2010 and sent it to Simon Fraser’s Writing Studio competition. It got on the short list. Happily it did not win and I worked on it for another year, editing and adding more poems. In 2011 I was lucky enough to be selected to participate in the Sage Hill Poetry Colloquium and work with Al Moritz. The final version of the book comes from that time.

I have a few suits of poems that were written at once. They are short, chapbook length. As a rule I write individual poems, that may or may not form a book.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy reading my poems. It is the sharing of the poem’s emotions with the audience that attracts me, the triggering of these emotions in the listeners, the sense of being heard and understood. There are times I find I don’t read well, that I don’t deliver, that I am not heard. It is very frustrating. The good part of that is it forces me to review a poem, to edit even a “finished” poem. I often read that poem again to see if the tweaking changed the audience response to the piece. In that sense performing is a part of my creative process.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t have a particular theory that I apply to my writing. I tend to think about the why and how of poetry, and the value of poetic expression in different cultures and times.

There are a number of topics that interest me and occupy my poetry. The fate of individual and families living in a totalitarian regime is one of them. They are denied freedom. What is freedom? Why do we seek it? These concerns underline my first book “small things left behind”. The book is published, but my interest is still there. I keep writing.

I consider myself a lyrical poet, still grappling with the life’s love-death-remembrance that constantly bubbles underneath our everyday (often mundane) going-on. My second manuscript (which is at the moment still searching for a publisher) came out of this minor obsession.

Another minor obsession: Why do people kill in the name of better, more ideal world? Terrorism is not a new phenomenon. It has been present throughout our history. There are periods that it catches minds like wild fire. I look at the time prior to the Russian Revolution and ponder why would a woman mathematician born into nobility or a poet see killing as a way to happiness for mankind. Poetry gives me a tool to explore, but the poems come slowly, so far too slowly to put a collection together.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I see myself as a poet, which in my mind is different from the general “writer”. I come from the period in Russian culture where poets were considered to be the oracles, the prophets. Poets, such as Evtushenko, were gathering stadiums full of listeners. I come from a culture where poets were imprisoned or killed for their verses, where readers were imprisoned or killed for reading their poetry. Despite that I live in a different culture and different times, the period and the culture I came from sets (and sometimes confuses) my attitude towards poetry and poets. Here and now, I think poets give voice to people who can’t speak. We hear more of the world and can put it into words.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I find the process of working with an editor the essential experience. I am a perpetual editor, can’t leave the poem alone, nothing is final. Somebody has to stop me. Besides, I like to be questioned. I’ve been lucky to work with Peter Midgley. I found respect and understanding. It’s been a rewarding process.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Hard to choose. The one from Nikolai Ostrovsky I learned as part of the Soviet brainwashing at a very early age “Life is given once and you must live it such a way as not to feel torturing regrets for wasted years”. I always treated it with sarcasm and mocking. It is enough to say just a few words of the sentence and every former Soviet would start laughing. But I realize more and more that I apply it to my life, and Churchill’s “Never give in, never, never…”. These two gentlemen often bring me to a sharp corner. That’s where I remember The Beatles’ “Let it be, let it be”.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t have any writing routine. It happens any time of the day, sometimes in a car in a parking lot, or in the doctor’s office. When I travel I often stop in the middle of the street to write something down. But I am most productive at my computer in my office at home. I am a late raiser. I don’t function well in the morning. I often get to my desk by noon.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I usually don’t do anything. Just wait until it comes back. Since I don’t work on a particular topic or book at any given time, I don’t feel the need to write more poems to finish the project, so I don’t feel stalled. There are simply times I don’t feel like writing. That time usually passes. As far as inspiration - it is inside.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Freshly baked yeast dough. Flowering Mock Orange. Keemun tea. Melting snow.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music. Paintings. Architecture. Autumn.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Jane Austen. Pushkin: I reread his Evgeny Onegin every 5-6 years and find a new meaning every time and am as taken by the beauty of his verse as when I was 15 years old. Anna Akhmatova. Josef Brodsky.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to learn to sing.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

For me it is the other way around. I have already been: an accountant, an auditor, systems analyst, caterer, glass artist, business owner. I came to Canada without any English. Writing was not in the cards. I am happy that I ended up being able to be myself – a poet.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I actually do a lot of something else, but nothing else engages my whole being the way writing poetry does. I feel truly alive as the words form in my head and then miraculously become a poem.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

A couple of books comes to mind: Olga Grushin Dream Life of Sukhanov and Vera by Stacy Schiff. Movies: Kaos , Character, The Return .

19 - What are you currently working on?

I see two books forming from what I am writing now.

The topic of individual/collective fates in the 20th century totalitarian countries continues to occupy me. I have written a number of poems about my family history. It started from “100 years of family guns” and as I continue I see the book growing out of it.

I have a lot of poems written while traveling that have a unifying theme and voice despite being written over a long period of time and in different countries. One day I hope it will become a book.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 13, 2014 05:31

October 12, 2014

Sawako Nakayasu, The Ants

Art Project

I am observing an ant trail from the tenth floor of a building, and photograph the exact same frame, once per second, sixty times, in order to have an accumulated minute of ants. Later, much later, I go back to the same exact spot where the ants once were, and place a grain of rice in the exact location of each ant in each frame. I am growing satisfied with the precision of my accumulation of ants and time as represented by grains of rice, until my postwar Japanese mother finds me and slaps me upside the head for wasting all that rice and tells me to get back inside and do my homework.

The deeper I enter Sawako Nakayasu’s new work,

The Ants

(Los Angeles CA: Les Figues Press, 2014), the more impressed I am through her blend of prose-poem, lyric short story and intricate meditative surfaces. Composed as a suite of short prose-poems, Nakayasu’s The Ants utilizes the subject of the ant to explore ideas far greater than those held simply to those of ants, and in deft, subtle ways that make you barely aware of such until you’re far deep inside. And yet, this is a book about, also, exactly what the title claims—ants—a subject matter that has occupied her work for some time. As she writes as part of the “Thank You” notes at the end of the collection: “INSECT COUNTRY is an ongoing investigation and tutelage under the auspices of the universe as lived by insects, mostly that of the ant variety. Works produced, conducted, performed, committed, or documented thus far include texts, performances, a collaborative book defacement, an open poetry studio, several chapbooks, a podcast, the naming of a non-collective, and various other plans involving film, dance, and music. Collaboration proposals are also welcome.”

The deeper I enter Sawako Nakayasu’s new work,

The Ants

(Los Angeles CA: Les Figues Press, 2014), the more impressed I am through her blend of prose-poem, lyric short story and intricate meditative surfaces. Composed as a suite of short prose-poems, Nakayasu’s The Ants utilizes the subject of the ant to explore ideas far greater than those held simply to those of ants, and in deft, subtle ways that make you barely aware of such until you’re far deep inside. And yet, this is a book about, also, exactly what the title claims—ants—a subject matter that has occupied her work for some time. As she writes as part of the “Thank You” notes at the end of the collection: “INSECT COUNTRY is an ongoing investigation and tutelage under the auspices of the universe as lived by insects, mostly that of the ant variety. Works produced, conducted, performed, committed, or documented thus far include texts, performances, a collaborative book defacement, an open poetry studio, several chapbooks, a podcast, the naming of a non-collective, and various other plans involving film, dance, and music. Collaboration proposals are also welcome.”Desert Ant

Says “and” with every step, so that it sounds like this: “and and and and and and and and and and and and and,” and so on. By the time I make my way to the same desert, I have been collecting and carrying an accumulation of nouns over the past, oh I don’t know how many days, and so I insert them in between the steps of the ant. Cilantro, tennis, phone, hand. Needle, rock, hair. Mingus. Monk. Mouth. I have been ignoring the dirty looks the ant keeps giving me, but finally I cave in, which means I stop to listen carefully. I am informed that I have thrown off the rhythm of “and and and and and.” I am informed that this shall not continue. I am given several options. I choose Monk, so for a while we do “Monk and Monk and Monk and Monk and Monk and Monk and Monk.” I thought we were doing okay, but before I know it the ant is out of sight, and then before I know it, the ant has made a decision, and then before I know it, the ant is in my mouth, and mouth, and mouth, and mouth, and mouth, and mouth, and mouth.

The author of a small handful of prior works, including Texture Notes (Letter Machine Editions, 2010) [see my review of such here], Hurry Home Honey (Burning Deck, 2009) and Mouth: Eats Color –Sagawa Chika Translations, Anti-translations, & Originals , as well as being translator of The Collected Poems of Sagawa Chika (Canarium Books, 2014), The Ants manages to accomplish something far greater than the sum of its parts, utilizing the short prose accumulation structure of her Texture Notes (another remarkable book I would highly recommend) to further her structural linkages between and through a suite of interconnected poems that sit in the crux of lyric poem, prose and short essay. The remarkable thing about this work is just how smoothly she writes about ants and not-ants, utilizing a series of serious and semi-serious explorations, inquiries, memories and even dreams to speak of such small, seemingly-insignificant creatures as well as larger issues of human interaction, social and political responsibilities and the whole of human civilization. Is this merely a book about ants? No, but this is very much, too, a book about ants.

Sign

Look at all those years upon years of co-called civilization and enlightenment and industrialization and this is where it has brought us. Are we any smarter? No. Are we any happier? No. Are we any prettier? No. No. None of the promises came true, and all we have to show for anything is that we can now sign in to all our favorite high-security locales using an ant proxy that sits behind the liquid of the computer monitor, and this is the truest sign of bratwurst or frog legs or pro-wrestling, oh I just can’t say it, that mythical p-word that means that we are somehow doing better than we were before.

Published on October 12, 2014 05:31

October 11, 2014

10 1/2 months;

Given I was adopted at ten months, Rose is now the age I was when I became me ("I've been me most of my life," I tell people), and have been lately comparing images of her to the earliest ones I have of myself ("at 10 1/2 months," mine says on the back). At least so far, I have no baby photos. Is it strange to make such comparisons? I know I have photos of Kate at the same age, somewhere, but so much has been in storage for so long, I still seek them out.

Published on October 11, 2014 05:31

October 10, 2014

Blog Hop: what the stories make of us,

The lovely and talented Montreal writer Tess Fragoulis (who we really don’t hear enough from) tagged me in this “Blog Hop” meme [her answers to the same questions are posted here]. I agreed to participate before I realized that I had already done such, under a different title, earlier in the year. Given that I answered such on my current poetry work-in-progress (our wee babe adds much, but slows all projects down, as you might imagine), I thought it might be worth going through the process again (especially since I’d already said yes) for the sake of my current fiction work-in-progress.

The lovely and talented Montreal writer Tess Fragoulis (who we really don’t hear enough from) tagged me in this “Blog Hop” meme [her answers to the same questions are posted here]. I agreed to participate before I realized that I had already done such, under a different title, earlier in the year. Given that I answered such on my current poetry work-in-progress (our wee babe adds much, but slows all projects down, as you might imagine), I thought it might be worth going through the process again (especially since I’d already said yes) for the sake of my current fiction work-in-progress.[Photo of myself on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 4, 2014, taken by Stephen Brockwell]

What are you working on?

For the past couple of years, I’ve been accumulating a collection of short stories tentatively titled “On Beauty.” I’m not entirely convinced by the title, but have set such considerations aside for a while, allowing myself to focus on the stories themselves.

The collection is made up of roughly eighteen short stories, each constructed to be roughly three manuscript pages in length (I suspect the manuscript is nowhere near long enough yet). What appeals to me is in a compact exploration of character and situation, attempting to say an enormous amount in a very small space in the most compact language possible. What appeals are those small or large moments of a character’s life or consideration that have enormous repercussions later on, even if that character might not be aware of the whats and the whys of those triggers. We are such complex creations, and so little of what we do, what decisions we make and why are really understood, even in the midst of our actions. My fiction appears to focus quite heavily on that, for reasons I, myself, have yet to determine.

The title originally came from picking up a copy of the Zadie Smith book of the same name; I’d read a piece by her in Brick: A Literary Journal a few years back and been extremely impressed [I even wrote about that here], so when I saw such at a used bookstore in Perth, Ontario (the former BackBeat Books and Music, when Christine McNair and I did a reading there), I had to pick it up. I have to admit, the book didn’t strike me—I suppose it wasn’t whatever it was I thought I expected (I know this is my issue and not hers); I was surprised by the information overload Smith was providing, and I felt that however skilled the work, there was just too much in the way of what I wanted from the story (I’ve since gone through a collection of her essays, and the book was spectacular).

I am interested in the small moments, and in brevity, wishing to include only the information that is essential to the story. I am not interested in providing needless physical description, for example. So much can be suggested through so very little; and so much of it distracts, and has nothing to do with the goings-on of the action (or, inaction) itself.

So far, I’ve had stories from the manuscript appearing in a few venues, including online at Numero Cinq , matchbook lit , Control Lit Mag and The Puritan , in print at Grain magazine, Matrix magazine and Atlas Review, and one forthcoming this month in The New Quarterly .

There was a period I’d hoped to complete the manuscript before the baby arrived, but that didn’t happen; then I’d hoped to complete the manuscript before Christine’s maternity leave ends in November, but I don’t really see that happening either. Now I’ve got my eyes set upon spring. Optimistically.

It might not be moving as quickly as I might like, but I’m still pretty pleased about it, overall. It feels as though I am accomplishing something that is really moving my work forward in a very positive direction.

How does your work differ from others of its genre?

I would think the lyric density alone might be enough to differentiate my work from the work of others in the same genre. I also tend to steer clear of dialogue.

I also tend to focus on particular moments, often leaping over a whole slew of action sequences: the moments of my fiction appear to either work up to a particular action, or away from a particular action, exploring the results of such. There is so much more to explore after the effects of an action, as opposed to the action itself.

I admired very much an episode of Mad Men that, instead of focusing on a particular wedding (which, narratively, wasn’t terribly important), decided to focus on what happened around and after that wedding. So many television programs would have focused on the wrong thing: a wedding episode. There is something about well-written television and film (such as Mad Men, or the film Smoke ) that have prompted my fiction for quite some time. How does one tell a story without giving anything away, and yet, leaving enough space to suggest what hasn’t been shown?

Of course, also, the decade-long swath Brian Michael Bendis recently finished carving through The Avengers over at Marvel Comics (he’s currently working his way through an impressive run at All-New X-Men ) is a display on how long-form storytelling is constructed: magnificent.

Why do I write what I do?

I think anyone writes the way they do because it is the only way they know how. Throughout my twenties, during my first few attempts at fiction, it took me far too long to abandon ideas of what I thought fiction was supposed to be and look like, instead of attempting to discover exactly the form that worked best for my own writing, and my own processes. Once I finally managed to clear that hurdle, it was far easier to continue and complete manuscripts that I was happy with.

We do what we do because we can’t do it any other way. And yet, experimentation and exploration are (obviously) essential to any writer’s craft and development. But I could never be able to (even if I wished to) compose a straightforward literary work akin to, say, David Adams Richards or Guy Vanderhaeghe. Even as a reader, the form simply doesn’t appeal.

When it comes to fiction, I’m difficult to impress: I often consider literary fiction to be far too long and wordy, and overly and unnecessarily descriptive, and so the amount of books of fiction I deliberately stop reading mid-way through are endless. Fortunately, I have been enormously impressed by recent works of fiction by Tessa Mellas, Marie-Helene Bertino, Lydia Davis, Lorrie Moore, Lynn Crosbie, Ken Sparling, Michael Blouin, Jim Shepard and Douglas Glover (for example). It does happen; I just wish it would happen more often.

A decade back, I was amazed to finally read Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections (despite finding many of his non-fiction opinions rather annoying); it was one of the first books over two hundred pages I’d read that I couldn’t see to excise a single word.

I’m currently in the midst of the new Diane Schoemperlen collection, and am duly impressed (as I suspected I would be—I love her work).

How does my writing process work?

Slowly, and accumulatively. I begin with longhand, and once I’ve exhausted such, I enter fragments, sections, sentences and paragraphs into the computer. I then print out the story-in-progress and spend time scribbling on the page, adding and subtracting, and composing additional fragments via longhand in my notebook to then return to the computer and go through the process again. Some of the stories in the manuscript-so-far have gone through this process daily for many months. Some have taken nearly three years to complete, and others I haven’t quite decided on yet. There is still much to do.

For further interviews, I tag thee: Cameron Anstee; Aaron Tucker;

Published on October 10, 2014 05:31

October 9, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Anna Leventhal

Anna Leventhal is a Journey Prize-nominated author originally from Winnipeg and currently based in Montreal. Her work has been published in Geist, Matrix, Maisonneuve, The Montreal Review of Books, and several short fiction anthologies, and has been broadcast on CBC radio. She won a Quebec Writing Competition award and was shortlisted in the Canada Writes: Hyperlocal competition. She was contributing editor for the Invisible Publishing collection

The Art of Trespassing

. Her first collection of short fiction,

Sweet Affliction

, appeared in April 2014.

Anna Leventhal is a Journey Prize-nominated author originally from Winnipeg and currently based in Montreal. Her work has been published in Geist, Matrix, Maisonneuve, The Montreal Review of Books, and several short fiction anthologies, and has been broadcast on CBC radio. She won a Quebec Writing Competition award and was shortlisted in the Canada Writes: Hyperlocal competition. She was contributing editor for the Invisible Publishing collection

The Art of Trespassing

. Her first collection of short fiction,

Sweet Affliction

, appeared in April 2014.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

This is my first book. It's been out for about a month; most of my friends are still talking to me, so maybe they haven't read it yet. Not much has changed, except for how I'm now super rich.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I like character and I like narrative voice, and those two things are very present in fiction. Maybe it's because I need distance? I used to do some theatre, and I could only really get into a character if I was allowed to do an accent. Otherwise I felt too self-conscious - I'd get paralyzed with how weird my own voice sounded to my ears. Even if it was a terrible embarrassing accent that no one should ever have to listen to, it gave me enough distance from myself to get really into whatever I was doing. Fiction might be something like that - the idea that you can get into another person's senses and temporarily forget that you're the one ultimately calling the shots. Fiction is the easiest way for me to lose myself in the work.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don't take notes in preparation to write a story. Usually I have an idea for a first line, or the vague shape of a character, or a dynamic between characters that I want to sit with for a while. From that point it's fairly steady going - but getting to that point can take ages. I can tool around for weeks, looking for the right tone or angle. I revise a lot but try to write a full first draft before I go back and tinker too much.

I'm never sure exactly where a short story is going to end up. There's a point in the writing at which I always think "This could be a novel. This could be Moby Dick." But then the narrative possibilities start to collapse on themselves and I see the story heading toward an end point that is much closer than I might have thought.

4 - Where does fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

When I started Sweet Affliction I did have the idea that it was going to be a book, not just a "collected works" kind of thing. I had characters I wanted to carry over from one story to the next, I had a vibe (for lack of a better term) I wanted to run with. I had themes I wanted to think about, many of which overlap in the stories. That said, I didn't write the individual stories with the other stories in mind, or only peripherally so, like background noise that you can tune out if you want to.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I really like reading out loud, not just my own writing but in general. So I enjoy public readings for that reason, on purely pleasurable terms. In terms of it contributing to my process, I probably get more insight into my work from hearing other people read it than I do from reading it myself. A reader with a good voice can totally change the way you think about what you've written. I'd like to have Gordon Pinsent on retainer.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The main question I try to answer is How do we live? That's a question with theoretical, ethical, and practical answers. More specifically I'm interested in the weirdness of having a body, how we reproduce (people, yeah, but also ideas, structures, problems), what sticks us together and pulls us apart, what makes us do what we think is the right thing.

By definition I think all writing is concerned with transformation, but I don't think about that too hard when I'm writing.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Revolution.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Try to err on the side of doing something.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

There's the ideal writing day and the typical writing day. On the ideal day I get up, run 5 k, eat breakfast, make coffee, sit down and pound out masterful prose for a few hours, nap, go to my day (night) job. Maybe see a friend for coffee somewhere in there. A typical writing day I make coffee, stare at my computer, check the internet, open a word file, realize I'm out of coffee, make more coffee, check internet, reread what I wrote the day before, pace around, flip through the work of a real writer, make more coffee, realize I'm too caffeinated to write, clean my house, decide I've had enough and watch Buffy for four hours. I aim for the ideal, usually end up closer to the typical.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

For me writing is born less of awe or beauty than of bemusement, frustration, estrangement, confusion. So if I need fuel I can ride the bus, hang out at a bar, watch people in a park or hospital. I get a lot of ideas for writing while on public transit or airplanes. Something about the proximity to humans and the lack of breathable air.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cigarettes and cat pee.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Once a spider wove an entire perfect orbital web on the chair on my balcony in the time it took me to write and then delete a single paragraph. I tried not to take it personally.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I think influence comes in several overlapping circles: writers who made you want to be a writer in the first place; writers who let you know it's okay to write about what you want to write about; writers you imitate or echo, consciously or not. A few of mine are Annie Dillard, Saul Bellow, Amy Hempel, Grace Paley, Miriam Toews, Sean Michaels, Melissa Bull, Jeff Miller, Michelle Sterling, Miranda July, Margaret Atwood, Flannery O'Connor, Greg Hollingshead, Denis Johnson, Arthur C. Clarke, Lynda Barry.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Learn to play piano.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think I'd have made a good surgeon.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

As poorly suited as I am to a life of writing, I'm way worse at everything else.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi; Jesus Christ Superstar .

19 - What are you currently working on?

A novel, a screenplay, and some new fiction. The novel's been marinating in my hard drive for half a year - I'm hoping that the next time I check on it, it will be unrecognizeable and amazing. The screenplay's gonna make me super rich. The new fiction's ultimate form hasn't totally revealed itself yet but it's pretty fun - it's about work and sex.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 09, 2014 05:31