Dave Armstrong's Blog, page 37

July 2, 2012

Reply to William Goode, Contra Sola Scriptura, Part 4 (Goode Denies the Infallibility of the Church; Is the Bible Its Own Judge, Minus the Church?)

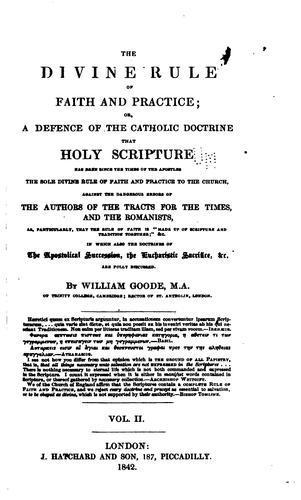

See the Introduction. Goode's words will be in blue. This installment is a response to portions of The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice , Volume Two (1853: second edition: revised and enlarged).

* * * * *

Having thus endeavoured to show, that Holy Scripture is our sole infallible and authoritative Rule of faith, we shall now proceed to prove, in like manner, in opposition to the doctrine that Tradition or the Church is the infallible and therefore authoritative Judge of the meaning of the Divine Rule of faith, that Holy Scripture is the sole infallible Judge of controversies respecting the truths of revelation. . . . By this position, then, we mean, that it is in Holy Scripture only that we can meet with any infallible determination respecting the points in dispute. When controversies arise. Scripture only can decide and terminate them; and if Scripture does not terminate them, it is either because they concern things which are not there delivered, and which, therefore, do not come to us with the authority of divine revelation, or because Scripture is misinterpreted; and in either case there is no further infallible authority on earth to appeal to for judgment. (p. 124)

Goode sets the stage for the next phase of the debate . . . I will be looking to see how much Scripture Goode can produce as supposed proof of his position.

The foundation upon which this truth rests is, as we have seen, briefly this; That as God is the only infallible Judge of controversies in religion, and as his voice can be recognised with certainty only in the Holy Scriptures, those Scriptures are consequently our only infallible Judge of controversies on earth. (p. 126)

Goode then suggests (on p. 127) Isaiah 8:19-20 (RSV, as throughout) as one such instance ("this is the rule by which all other informants are to be tried"):

And when they say to you, "Consult the mediums and the wizards who chirp and mutter," should not a people consult their God? Should they consult the dead on behalf of the living? [20] To the teaching and to the testimony! Surely for this word which they speak there is no dawn.

The problem with this exegesis is that it is not Scripture alone that is being referred to (as several Protestant commentaries will testify). It is, rather, the prophetic word that comes through Isaiah (more analagous -- strictly speaking -- to oral apostolic tradition than to Scripture). We see this from the context of verse 16, where Isaiah is commanded by God to "Bind up the testimony, seal the teaching among my disciples."

Goode then gives examples (p. 127) of Jesus sending the Sadducees and Pharisees to the Scripture for proof of His assertions. But this is not in dispute. Catholics use biblical prooftexts just as Protestants do, and argue on that basis (as a perusal of any papal encyclical or document of an ecumenical council or the Catholic Catechism will quickly prove). The question at hand is, rather, what happens when folks go to the Bible but come up with variant interpretations. What then? Catholics say that the Church and passed-down apostolic tradition (the history of doctrine) and apostolic succession decide. Protestants say that . . . well, they simply repeat that Scripture decides, but this is clearly no solution when men differ in their conclusions: each citing the Bible in his real or alleged behalf. They can say that till they're blue in the face; it won't resolve the practical problem of contradictory conclusions.

Hence it follows, that Scripture may be variously interpreted by men, and yet give in the sight of God an amply sufficient and clear judgment, to bring those in guilty before him who do not interpret it aright. And the reason is plain; because, in all important points, men are prevented only by their own prejudices, corruption, or carelessness, from rightly understanding it. (p. 128)

No doubt sin is often a factor, but this, too, is too simplistic. I call this refrain "the sin argument." Protestants use this whenever someone else interprets the Bible in a way that they think is incorrect. They quickly conclude that it is sin or stupidity that is the cause (in the other guy, of course). This almost mocks entire traditions in Protestantism that disagree with each other. How are these conflicts resolved? By each group accusing the others of sin and intellectual carelessness?

Luther differed with Calvin on the nature of the Eucharist. Both men differed from the Anabaptists, who held to adult believer's baptism only (and were drowned because of it), and disagreed with each other as to what baptism conveyed. Equally brilliant men (equally adept at Bible scholarship) arrive at completely different conclusions. Because of this, we need a final say that is separate from the Bible itself. The logical answer is: the Church: itself mentioned as authoritative in Scripture. And we observe the Church infallibly deciding on a doctrinal issue (whether Gentiles ought to be circumcised or to follow Jewish law in its entirety) in the Jerusalem Council of Acts 15).

Shall we say, then, that the Scriptures containing that word are insufficient, and ill calculated to act as a judge now to us on earth, when we are told expressly, that that word will be our judge at the future day of account? (p. 128)

No. Scripture is sufficient in and of itself to judge between doctrinal truths and falsehoods on almost all matters that come up. What we "shall" say is that fallible, fallen men still clearly need an infallible teaching body, that will prevent the inevitable dissension from arising among men (for whatever reason). Christians need one body, one faith, one voice to keep unity. We've all seen what the Protestant principle has resulted in: many hundreds, if not thousands of competing denominations.

Is it not equally calculated to act as a judge now to us on earth, as it will be at the future day of account at the bar of Christ? And if by that word we are to be then judged, then the statements of that word are clear and determinate, and sufficient of themselves to determine all controversies on the essentials of the gospel at least; and it will be our wisdom to use it now for the same purpose, and "judge ourselves" by it; making that our rule of judgment here, by which we are to be judged hereafter. And if this is done with simplicity and sincerity, and prayer to God for his blessing, we know, from the promises of a faithful God, that such an inquirer shall not err fundamentally. (p. 128)

It's remarkable that Goode can summon up all this sunny, optimistic, idealistic faith in a system that has clearly (in practice; in history) failed to produce doctrinal unity by these principles. A "faithful God" will bring about the attainment truth for the individual. Indeed He can, and does do so. That is not our beef; we say that if Goode has all that faith in God guiding individuals, why does He lack it, with regard to God leading His Church as a whole, and preserving it from doctrinal error? Is God too limited to do that?

Apparently, Protestants think that He is, because they always deny the very possibility of an infallible Church. Catholics have much more faith than that: we believe that God is powerful and good enough to guide His Church (composed of sinful human beings), and through the Church, all Christians, to attain to the highest theological and spiritual truths. We don't tie God's hands, or casually deny that He is able to do what is plainly needed to bring about unity in doctrinal matters.

And is it to be argued, that, because of this, that is, because men cannot be brought to see and confess the truths there revealed, the revelation is insufficient to show men the truth? The question is, not whether men interpret the Bible variously, but whether, that being the case, the fault is not in man, and not in the Bible being fairly open to different interpretations in the essentials of the faith? (p. 139)

This is beside the entire point and the problem. The difficulty is not at all due to the insufficiency of the Bible. The difficulty lies in the fact that a book (even an inspired one) is not automatically self-interpreting, to such an extent that all reasonable and good men will completely, spontaneously agree with the doctrines that it truly teaches. Even reasonable and good men (forget all the sinners and theological ignoramuses!) won't do that.

An authoritative Church is, therefore, necessary because of the frailties, fallibility, and folly of men. We can argue pipe-dream abstracts and unattainable ideals all day long with Protestants (men should come to agreement based on the Bible Alone, so Goode tells us, with all faith and a sparkle in his eye), but the fact remains that this system and rule of faith is not working, and people are being led astray and led down the road to hell every day by virtue of accepting some false doctrine promulgated by the denomination they happen to be in. It's denominationalism and individualistic folly that the Bible never countenanced at all.

If truly the Bible alone was able to put an end to all controversies, why does the Church of England (Goode's denomination) have a creed at all (Westminster Confession), or its 39 articles? Why bother? If authoritative pronouncements are completely unnecessary, since Scripture has all that covered, and all truth is perfectly evident in it to one and all, why have those? But it does, and it does so because it is instinctively realized (by this sect and virtually every other Christian group) that men benefit by creeds and confessions of faith. As soon as one even summarizes Scripture by such means, human involvement or "tradition" if you will, is involved. There is no way out of it.

Again, I stress that the Catholic objection has nothing to do with running down the intrinsic merits of inspired Scripture: God's unique revelation. It has everything to do with how men receive (or don't receive) and interpret that revelation. God has given us the gift of the Church in order to confirm biblical truth and to guide men on the right course. It's not like this is something that the Bible does not refer to. There is such a thing as a Church (!!), and it does have those dreaded, despised attributes of authority and indeed, infallibility!

It is necessary for the well-being of the Church to lay down what it holds to be the doctrines of Scripture as a protest against the misinterpretations of heretics, and to expand that Confession of faith from time to time according as heresies arise, in order to keep her communion as far as possible pure. And this holds good of a particular Church as well as of the whole Universal Church. (p. 155)

Exactly! How this doesn't concur with what I have been arguing, I will let you, the reader, judge. But, as we saw before, Goode can occasionally make a statement like this, but immediately disclaim any strong authority to make a creed binding, or (heaven forbid!) a Church claiming to be infallible: that most dreaded of all scenarios.

When the authorities of any Church separate one who obstinately maintains what they deem to be fundamental error from their communion, they do so, not as persons possessing any infallible guide besides the Scriptures, but in the exercise of the ministerial authority given to them by the Church, and each party is responsible to the great Head of the Church alone for their conduct. (pp. 157-158)

This is what is called "a distinction without a difference." Folks can be removed from a Christian group for denying what that group holds in important particulars; yet everything held by the group is always provisional (never ever ever infallible) and perpetually subject to correction from any individual in the group? Does that mean that a Luther-like individual can be removed from a denomination for being a good Protestant, exercising his conscience and private judgment? It certainly does mean that; once we follow through with the logic involved. That makes no sense at all, but it is an inevitable state of affairs, given the illogical chaos of private judgment, never-ending denominationalism and sola Scriptura.

* * *

Published on July 02, 2012 15:09

Reply to William Goode, Contra Sola Scriptura, Part 3 (Oral Tradition in the NT; Fathers vs. Tradition?)

See the Introduction. Goode's words will be in blue. This installment is a response to portions of

The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice

, Volume Two (1853: second edition: revised and enlarged).

See the Introduction. Goode's words will be in blue. This installment is a response to portions of

The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice

, Volume Two (1853: second edition: revised and enlarged).* * * * *

Further, it is to be considered, that the gospel was not a revelation altogether new, being, in all its great features at least, only a development of the types and prophecies of the Old Testament, where the language of the inspired writers of the New Testament leads us to recognise a very full adumbration of its whole doctrine. Thus, St. Paul describes himself to Felix as believing all things written in the law and the prophets, with a manifest reference to his Christian faith, (Acts xxiv. 14.), and when arguing with the Jews, he reasoned with them out of those Scriptures, (Acts xvii. 2.), and says, that the revelation of the mystery of God in the Gospel is "by the Scriptures of the prophets, according to the commandment of the everlasting God, made known to all nations for the obedience of faith." (Rom. xvi. 26.) (p. 74)

This is true. The two Testaments are harmonious: the New being a consistent development of the Old. Sola Scriptura is not observed in either one, as I have been demonstrating.

Consequently, we have, even in the Old Testament, an adumbratory representation of all the great truths of the Gospel. Are we, then, to suppose, that when besides this we have four different accounts of the doctrines and precepts which our Lord delivered while on earth, and above twenty epistles by the Apostles to different churches, that we must still go beyond the Scriptures to find any important truth? (p. 74)

Catholics believe in the material sufficiency of Scripture, too. We deny its formal sufficiency as a rule of faith. It has to be interpreted within the framework of an infallible tradition and Church (it doesn't follow from that, that either is "above" Scripture). Failing that, we get the chaotic situation in Protestantism, with multiple hundreds of contradictory doctrines, and consequently, necessarily much falsehood being believed. That was never God's will, because He is the God of truth. The devil is the one who is the father of lies; hence every falsehood is giving glory to him, not God.

. . . our opponents seem to think, that they have a ready answer, for they say, that Scripture itself is in favour of their doctrine of Tradition. (p. 75)

Indeed it is.

I shall now, then, proceed to consider the passages adduced by them in proof of this assertion, and show how utterly destitute of foundation is the argument so raised. (p. 75)

Excellent!

To sum up all, then, in one word, what Mr. Keble and the Romanists have got to prove, before they can in any way avail themselves of these passages [1 Tim 6:20; 2 Tim 1:14; 2:2], is, (1) that Timothy's deposit embraced something of importance not in Scripture; and (2) that Patristical Tradition is an infallible informant as to what that deposit was; which are precisely the two points "assumed with some confidence," with scarcely an attempt at a proof. (p. 78)

This is a fair and valid point. I would agree that passages of this sort are not strong or definite "proofs" of a precise nature, etc. On the other hand, I would contend that they offer a contextual framework in which the notion of an authoritative tradition makes sense; and is (apart from the questions of particulars and specificity) plausible. Secondly, it is just as difficult (if not more so) to argue that mentions of such oral tradition could not possibly contain anything not explicitly dealt with in Scripture, as it is to positively speculate upon what exactly is being referred to. Because of the lack of particulars, both cases are difficult to make in a compelling fashion (from passages such as these), since both necessarily entail mere speculation.

Another of the passages brought forward by our opponents in support of their views, is that in 2 Thess. ii. 15. "Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions which ye have been taught, whether by word or our epistle." And I will venture to say, that, beyond the occurrence of the word "traditions" in it, there is not a pretext for so applying it. The Epistles to the Thcasalonians, we must observe, were, with the exception possibly of St. Matthew's Gospel, the first written of all the books of the New Testament. And St. Matthew's Gospel was written more especially, in the first instance, for the use of the Jewish converts. Consequently the Thessalonians had, at the time when these Epistles were addressed to them, no other books of the New Testament. . . . Much, therefore, at least, that we learn from the Scriptures, must have been communicated orally to the Thessalonians by the Apostle; as, for instance, the ordinances of Baptism and the Lord's Supper. They had no Scriptures professing to give them an account of our Lord's Gospel. And these were traditions which they had themselves received from the mouth of the Apostle himself. And who denies, that the oral teaching of the Apostles was of equal authority with their writings? So that the argument from this passage runs thus, — Because the Thessalonians, when destitute of the Scriptures, were exhorted by the Apostles to observe all things that he had himself delivered to them, either orally or by letter, therefore we, possessing the Scriptures, are to conclude, that there are important points of Apostolical teaching not delivered to us anywhere in all the various books of the New Testament, and are bound to receive Patristical Tradition as an infallible informant on such points. Now the chief question at issue is, whether we have that oral teaching, in any shape in which we can depend upon it, in the writings of the Fathers. (pp. 79-80)

To make this passage at all suitable to their purpose, they must show, that there was something important in the oral teaching of the Apostles, which is not to be found in any of the books of the New Testament; a notion, against which we can array the whole body of the Fathers; (of which it is apparent from Mr. Newman's thirteenth Lecture that our opponents are fully conscious; although they attempt to get over the difficulty, by asserting, that, though all things essential are there, yet they are there so latently, that we cannot find them, until Patristical Tradition has pointed them out ;) or at least they must prove, that the Patristical report we possess of the oral traditions of the Apostles, is an informant sufficiently certain to bind the conscience to belief. The same answer will suffice for a similar passage in a subsequent part of the Epistle, viz., 2 Thess. iii. 6. (p. 81)

My present purpose is not to engage in a patristic debate (I'm sticking to strictly the biblical arguments made on both sides), but in passing I will cite St. Augustine -- held in the very highest esteem by both Catholics and Protestants --, and show how far off the mark Goode is, with regard to patristic thought. Lutheran Church historian Heiko Oberman notes concerning St. Augustine:

Augustine's legacy to the middle ages on the question of Scripture and Tradition is a two-fold one. In the first place, he reflects the early Church principle of the coinherence of Scripture and Tradition. While repeatedly asserting the ultimate authority of Scripture, Augustine does not oppose this at all to the authority of the Church Catholic . . . The Church has a practical priority: her authority as expressed in the direction-giving meaning of commovere is an instrumental authority, the door that leads to the fullness of the Word itself.

But there is another aspect of Augustine's thought . . . we find mention of an authoritative extrascriptural oral tradition. While on the one hand the Church "moves" the faithful to discover the authority of Scripture, Scripture on the other hand refers the faithful back to the authority of the Church with regard to a series of issues with which the Apostles did not deal in writing. Augustine refers here to the baptism of heretics . . .

(The Harvest of Medieval Theology, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, revised, 1967, 370-371)

Likewise, Anglican Church historian J. N. D. Kelly comments on Augustine:

According to Augustine [De doct. christ. 3,2], its [Scripture's] doubtful or ambiguous passages need to be cleared up by 'the rule of faith'; it was, moreover, the authority of the Church alone which in his eyes [C. ep. Manich. 6: cf. De doct. christ. 2,12; c. Faust Manich, 22, 79] guaranteed its veracity.

(Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, fifth revised edition, 1978, 47)

Thus, the two renowned Protestant Church historians above directly contradict Goode's assertion that the Protestant "can array the whole body of the Fathers" against the notion of "an authoritative extrascriptural oral tradition" (Oberman's description of St. Augustine's position). Hence, St. Augustine observed:

As to those other things which we hold on the authority, not of Scripture, but of tradition, and which are observed throughout the whole world, it may be understood that they are held as approved and instituted either by the apostles themselves, or by plenary Councils, whose authority in the Church is most useful, . . . (Letter to Januarius, 54, 1, 1; 54, 2, 3; cf. NPNF 1, I, 301)

I believe that this practice [of not rebaptizing heretics and schismatics] comes from apostolic tradition, just as so many other practices not found in their writings nor in the councils of their successors, but which, because they are kept by the whole Church everywhere, are believed to have been commanded and handed down by the Apostles themselves. (On Baptism, 2, 7, 12; in William A. Jurgens, editor and translator, The Faith of the Early Fathers, three volumes, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1970 and 1979 [2nd and 3rd volumes], Vol. III, 66; cf. NPNF 1, IV, 430)

[F]rom whatever source it was handed down to the Church - although the authority of the canonical Scriptures cannot be brought forward as speaking expressly in its support. (Letter to Evodius of Uzalis, Epistle 164:6; NPNF 1, Vol. I, 516)

But those reasons which I have here given, I have either gathered from the authority of the church, according to the tradition of our forefathers, or from the testimony of the divine Scriptures, or from the nature itself of numbers, and of similitudes. No sober person will decide against reason, no Christian against the Scriptures, no peaceable person against the church. (On the Trinity, 4,6:10; NPNF 1, Vol. III, 75)

For many more similar examples in the fathers, see my book, The Church Fathers Were Catholic: Patristic Evidences for Catholicism and my web page on the Church fathers.

Mr. [John] Keble [see biography] proceeds to cite two other passages in support of his view.

Much later, we find St. Peter declaring to the whole body of Oriental Christians, that in neither of his Epistles did he profess to reveal to them any new truth or duty, but to 'stir up their minds, by way of remembrance of the commandment of the Apostles of the Lord and Saviour.' (2 Pet. iii. 1.) St. John refers believers for a standard of doctrine, to the word which they had heard from the beginning, (1 John ii. 24,) and intimates, that it was sufficient for their Christian communion, if that word abode in them. If the word, the commandment, the tradition, which the latest of these holy writers severally commend in these and similar passages, meant only or chiefly the Scriptures before written, would there not appear a more significant mention of those Scriptures: something nearer the tone of our own divines, when they are delivering precepts on the Rule of faith? As it is, the phraseology of the Epistles exactly concurs with what we should be led to expect; that the Church would be already in possession of the substance of saving truth, in a sufficiently systematic form, by the sole teaching of the Apostles. (pp. 22, 23.) (pp. 81-82)

These are two excellent biblical indications of a robust oral apostolic tradition. St. Augustine refers back to such things and gives them the utmost respect, but Goode proceeds to mock Keble's sensible application of them:

I have given the passage in full, to show the reader precisely Mr. Keble's mode of reasoning upon these texts; and one is almost tempted to ask. Can the writer be serious in making these observations, or is he sarcastically showing how utterly destitute of evidence is the cause he professes to defend? St. Peter and St. John (says Mr. Keble) refer Christians of their age to the commandments and instructions which they had received orally from the Apostles, and did not say to them, directly one or two books of Scripture had been written, (which they might or might not possess,) you must forget all which the Apostles told you, and be careful to believe nothing but what you find written in one or two books which have been published by the Apostles, which you must get if you can; and therefore we, who have all the books of the New Testament, including four accounts of the Gospel, who have never had any instructions from the Apostles, and are at the distance of eighteen centuries from them, are to take the Patristical report of their oral traditions as binding our consciences to belief. Such an argument, I must say, carries with it much more than its own refutation. (p. 82)

Goode caricatures Keble's argument, then shoots down the straw man (the oldest "sophist's trick" in the book). Keble (in the latter portion) is making an argument from plausibility, as I have done in previous installments. Goode admits that there is no express statement of sola Scriptura in the entire Bible. Keble, for his part, argues (quite sensibly and rationally) that if Scripture alone were in mind in these passages, that it is probable Bible passages would have been mentioned, since they so often are. Therefore, failing that, it is reasonable to conclude that tradition is solely or primarily in mind.

As to the "either/or" mentality that Goode's caricature presents: it isn't present in Keble's own words and argument. But Goode (note carefully) apparently must conclude that any deference to tradition at all has to be in some extreme exclusivistic / dichotomous sense that would exclude Scripture, and bind consciences. Keble (far as I can tell) is simply noting that there is reference to an authoritative oral tradition. Goode is incorrect in imagining that Keble is trying to prove anything more than that. He can legitimately quibble about content and application, but the presence of such tradition in the New Testament is beyond argument. Its repeated presence runs contrary to sola Scriptura. Goode can try to laugh that off and war against straw men, but such tactics won't advance his burden of proof at all.

There remain a few other passages, which are sometimes adduced by the Romanists on this subject, which it may be well to notice before we pass on; but they are precisely similar in character to that given above from the Epistle to the Thessalonians, and need no other explanation than what has been given for that. Thus, the Apostle says to the Corinthians, ''I praise you brethren, that ye remember me in all things, and keep the ordinances, . . . as I delivered them to you." (1 Cor. xi. 2.) Well; what were these traditions? Were they anything more than what we have in Scripture; and if they did include more, where is the informant who will certify us of them? Resolve these two questions, and then proceed to apply the passage accordingly; but until these questions are satisfactorily resolved, the passage will prove no more than that the Corinthians did right in following the precepts which the Apostle had given them, which nobody doubts. And we may observe, that the Apostle has told us, in a subsequent part of the same chapter, what one of these traditions was, viz., the institution of the Lord's Supper (See ver. 23 et seq.); and thus we see, that the only one of these traditions which is mentioned, we have (as we might expect) in the Scriptures of the Evangelists. (pp. 82-83)

Lack of specificity in these passages is far less a "difficulty" for us than lack of any statement at all in favor of sola Scriptura is a difficulty for the Protestant, who insists on making a biblically vacant notion (i.e., a purely man-made tradition) their very pillar of authority. Any authoritative tradition at all is fatal to the sola Scriptura position. but lack of specificity in many biblical passages referring to tradition is simply that: lack of specifics. It doesn't prove that such tradition doesn't exist, because we don't know all the particulars of it from Scripture alone. As Goode alludes to: we can reasonably deduce some of that content by the treatment of it in the fathers (as my Augustine example illustrated).

Both sides, therefore, deduce and make indirect arguments to some degree, from the biblical data. But it is a question of no direct biblical evidence (the sola Scriptura position) -- remember, Goode already conceded that -- vs. numerous biblical evidences, albeit of a usually vague and general nature. The former is a much greater difficulty than the latter. And it's only one of many internal difficulties in the Protestant view, that taken together, prove altogether fatal to it.

* * *

Published on July 02, 2012 09:48

July 1, 2012

Reply to William Goode, Contra Sola Scriptura, Part 2 (Concession That the Bible Contains No Precise Statement of SS; OT Jews Accepted SS?; Jesus vs. Tradition?)

See the Introduction. Goode's words will be in blue. This installment is a response to portions of

The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice

, Volume Two (1853: second edition: revised and enlarged).

See the Introduction. Goode's words will be in blue. This installment is a response to portions of

The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice

, Volume Two (1853: second edition: revised and enlarged).* * * * *

Let it be observed, then, first, that it is not affirmed by us, that we have, in the Holy Scriptures, every thing that our Lord and his Apostles uttered; nor that what the Apostles delivered in writing, was of greater authority than what they delivered orally. It is undeniable, that we have not all that they delivered. St. Paul, in his Second Epistle to the Thessalonians, appears to allude to information which he had given them orally, and which he does not state in his writings. (2 Thess. ii. 5, 6.) It is likely that this might have been the case in some minor points. Nay, it is possible, that the Apostles may have given to some of their converts, on some occasion, a more full and luminous exposition of this or that doctrine, than what we find in Scripture. I will even add, that it is possible, that, as there has been a succession of God's people from the beginning, so the substance, or at least a portion of such additional matter, may have been propagated from one to another, and have thus come to the children of God of our own day, commended to the spiritual mind by its own light; but as far as regards any direct proof, or external evidence, of its Apostolical origin, utterly destitute of any such claim upon us; though I should rather, with Theodoret, attribute any similarity of sentiment that has prevailed among the children of God on such points, to their having all been partakers of the influences of the same Spirit. (p. 64)

We say not, that it embraces everything which God might have revealed, nor even all which the Apostles did actually deliver, but that it includes all which we can know to be of divine revelation. (pp. 65-66)

Sensible qualifications . . .

(1) Let us observe the arguments and objections derived from Scripture itself on this point. (p. 70)

Finally! Now we are to the necessary heart of the argument: proving it from Holy Scripture, and not some mere arbitrary assertions of men.

Now, here I admit at once, that there is no passage of the New Testament precisely stating, that the Christian Rule of faith is limited to the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament; and for the best of all reasons, viz., that such a statement would, at that time, (i. e., during the publication of the books of the New Testament,) have been utterly inapplicable to the circumstances of the infant Church, and untrue. For a little time there were no Scriptures of the New Testament, and the Scriptures which we possess were gradually written, and did not at once find their way into the whole Christian Church, and no one ever dreamed that the oral instructions of the Apostles were not, to those who heard them, as authoritative as their writings. (p. 70; my bolding)

This is nuanced and refreshing to see; however, it doesn't erase the self-defeating difficulties inherent in sola Scriptura. It creates even more, because the inspired writers could have easily made a general statement of the principle of sola Scriptura, to be fully implemented later. God is, after all, behind inspired writings. He knew that the New Testament was to be a known entity by the 4th century (just as inspired prophets in the Old testament knew the future: since God was guiding them with their prophecies). He could have led the Bible-writers to state that when Scripture was finally canonized and determined, once and for all, that it was to be the sole rule of faith.

Why in the world would He not do so? Why leave the so-called "pillar" principle to the fallible speculations and ruminations of men, rather than the authority of inspired Scripture itself? After all, the New Testament was already categorizing Paul's writings as Scripture (2 Pet 3:16). It could have, therefore, easily made a statement of this nature about Paul's writings, and also ( I would contend, as a plausibility argument) about the gospels, which were very well-established early on. That is the great bulk of the New Testament.

Thus, Protestants (by Goode's free concession) are forced to speculate in an extrabiblical fashion, as to the Bible being the supposed sole rule of faith? This has been my strong criticism all along: sola Scriptura (with the greatest irony) is a man-made unbiblical tradition. Goode is losing this debate by default: by his own fatal admission. Sola Scriptura is, I reiterate, by Goode's criterion, literally a tradition of men, since it's not in the Bible (so he says). Thus, it is subject to the same withering criticisms that Goode subjected all tradition whatsoever to in hundreds of pages in his first volume (we can't possibly trust it, etc.); where he argued that only the Bible can be such a guide.

If sola Scriptura is simply yet another fallible tradition of men, what good is it? To apply it to Scripture is to do exactly what Goode excoriates the Catholic Church for doing: applying authoritative interpretations to Scripture and demanding obedience to her authority in doing so. Thus, the Protestant must apply a very unProtestant principle (binding authority of a non-biblical principle) in order to make sola Scriptura their fundamental principle, which is utilized in constructing everything else in their theology. How odd, and how viciously self-defeating . . .

Goode freely admits that there is no such statement. Thanks, Mr. Goode! That saves me a ton of trouble proving that it doesn't exist (proving a negative always being difficult or impossible). My opponent graciously grants it. It may be his own death-blow, though . . .

They among whom the Scriptures were originally promulgated had been themselves hearers, — that is, very many of them, — of our Lord and his Apostles, and, to them, the unwritten word was as authoritative as the written. Consequently such a statement could only have been made as a prospective announcement, applicable only to a subsequent period of the Church. Was it, then, to be expected, was it, indeed, possible, that the Apostles should precisely fix the period at which, or the persons to whom, their writings would be the sole infallible Rule of faith, when, with the earliest Christians, it would evidently depend very much upon situation and circumstances, how far this was the case? (p. 70)

Of course it is entirely possible, plausible, and to be fully expected, if indeed sola Scriptura were true. Goode just finished, in the lengthy preceding section, showing how Scripture is inspired; i.e., God-breathed. Inspired Scripture includes infallible prophetic analysis of future events. The book of Revelation plainly does this. The mention of some supposed principle of sola Scriptura doesn't have to be date-specific, only content-specific (referring to the NT canon, as later to be determined).

St. Paul himself refers prophetically to future events:

Acts 20:29-31 I know that after my departure fierce wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock; [30] and from among your own selves will arise men speaking perverse things, to draw away the disciples after them. [31] Therefore be alert, . . .

So what is the great difficulty / impossibility of Paul or someone else clearly stating the principle of sola Scriptura: a thing that Protestant like Goode devotes three volumes and over 1000 pages explaining? Goode is straining at gnats.

But though we have not, and were not likely to have, such an announcement in Scripture, we have there what may answer as well, the determination of a parallel case, viz., that of the Jews at the time of our Lord's incarnation. We learn clearly from Scripture, that the Canon of the Old Testament was to them at that time (the divine voice being no longer heard among them) the sole Rule of faith; and that the traditions of the Fathers, notwithstanding their pretended divine origin, were not worthy of being considered the Word of God. (p. 71)

This is simply untrue. If Goode is relying on this argument, he will fail miserably. For one thing, the Pharisees, who were the mainstream Jewish group at the time of Christ, and the primary tradition from which developed Christianity, believed in the oral Torah. Moreover, the New Testament on several occasions, refers to extrabiblical tradition as authoritative ("Moses' Seat": Matt 23:1-3; a rock that followed Moses in the desert: 1 Cor 10:4; cf. Ex 17:1-7; Num 20:2-13; Jannes and Jambres: 2 Tim 3:8; 1 Pet 3:18-20 draws directly from the noncanonical book of 1 Enoch 12-16; Jude 9, 14-15 cites 1 Enoch 1:9; etc.).

That is only the beginning of the arguments against the Jews as allegedly sola Scriptura advocates. I've devoted two lengthy posts to these considerations:

The Old Testament, the Ancient Jews, and Sola Scriptura

Biblical Evidence for the Oral Torah (Hence, by Analogy, Oral Apostolic Tradition)

That the Scriptures of the Old Testament were to the Jews of that period the sole authoritative Rule of faith, we have, I conceive, very sufficient testimony in Scripture. In the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, our Lord himself evidently refers to them as bearing that character, when he makes Abraham reply to the rich man begging for some messenger to be sent to instruct his brethren on earth; " They have Moses and the prophets, let them hear them." (Luke xvi. 29.) And still more clearly, in his reply to the lawyer who asked him, "Master, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?" "He said unto him. What is written in the law? How readest thou?" (Luke X. 25, 6.) And so in the scene of temptation in the wilderness, he meets the tempter at every turn with the written word as his guide and rule. (Matt. iv. 1 — 10.) (p. 71)

All this proves is that Scripture is materially sufficient: a thing that Goode himself says is an agreement between Catholics and Protestants. Scripture is the most readily quotable source of authority, and used as such by Jesus (and by myself and Catholics all down through history). It doesn't follow that it is the only such source.

Further; to them and to them alone our Lord constantly appealed, in proof of the truth of his doctrine, as the rule of judgment. (p. 71; my bolding)

This is untrue. I already stated the example of "Moses' Seat" above. That is not an Old Testament terminology; it is straight from rabbinical tradition. After appealing to this, Jesus told His followers: "so practice and observe whatever they tell you" (Matt 23:3). Thus, He grounded pharisaic authority on a non-biblical principle, and then advised His followers to follow their teaching.

Moreover, Jesus cited or at least strongly alluded to -- dozens of times -- deuterocanonical texts (as is true of the entire NT), as we see in lists of such proposed references (such as Jimmy Akin's). Here are two examples:

1a) Mark 9:48 where their worm does not die, and the fire is not quenched.

1b) Judith 16:17 Woe to the nations that rise up against my people! The Lord Almighty will take vengeance on them in the day of judgment; fire and worms he will give to their flesh; they shall weep in pain for ever.

2a) Luke 12:20 But God said to him, `Fool! This night your soul is required of you; and the things you have prepared, whose will they be?'

2b) Wisdom 15:8 With misspent toil, he forms a futile god from the same clay -- this man who was made of earth a short time before and after a little while goes to the earth from which he was taken, when he is required to return the soul that was lent him.

Goode is thoroughly mistaken, if he thinks that the New Testament writers never cited anything as trustworthy tradition beyond the Old Testament.

"Search the Scriptures." (John v. 39.) "Ye do err, not knowing the Scriptures." (Matt. xxii. 29.) (p. 71)

Of course; proves nothing, however, of the truth of sola Scriptura. And so far from appealing to or even recognising any "tradition," he (as we have seen) only mentions traditions in the way of rebuke. See Mark vii. 1—13, where the "commandment of God" and "the word of God" are identified with Scripture, and put in opposition to the "traditions" of the Pharisees, which are called without distinction "the commandments of men." (p. 71)

This very common myth promulgated by Protestants, is also a falsehood. Jesus contrasted true apostolic tradition with the false traditions of men (false tradition is italicized; true tradition bolded):

Matthew 15:3 He answered them, “And why do you transgress the commandment of God for the sake of your tradition?”

Matthew 15:6 So, for the sake of your tradition, you have made void the word of God.

Matthew 15:9 “In vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the precepts of men.”

Matthew 16:23 But he turned and said to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a hindrance to me; for you are not on the side of God, but of men” (cf. Mk 8:33).

Mark 7:8-9, 13 You leave the commandment of God, and hold fast the tradition of men.” And he said to them, “You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God, in order to keep your tradition! . . . thus making void the word of God through your tradition which you hand on. And many such things you do.”

Now, if Goode and other Protestants want to quibble and say that Jesus doesn't use the specific word "tradition" (paradosis) positively, I retort that the usages above are (in context) equivalent. I showed this in my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism :

It is obvious from the above biblical data that the concepts of Tradition, Gospel, and Word of God (as well as other terms) are essentially synonymous. All are predominantly oral, and all are referred to as being delivered and received:

1 Corinthians 11:2: "Maintain the traditions . . . . even as I have delivered them to you."

2 Thessalonians 2:15 "Hold to the traditions . . . . taught . . . by word of mouth or by letter."

1 Corinthians 15:1 ". . . the gospel, which you received . . ."

Galatians 1:9 ". . . the gospel . . . which you received."

1 Thessalonians 2:9 "We preached to you the gospel of God."

Acts 8:14 "Samaria had received the word of God."

1 Thessalonians 2:13 "You received the word of God, which you heard from us, . . ."

2 Peter 2:21 " . . . the holy commandment delivered to them."

Jude 3 ". . . the Faith which was once for all delivered to the saints."

In St. Paul's two letters to the Thessalonians alone we see that three of the above terms are used interchangeably. Clearly then, tradition is not a dirty word in the Bible, particularly for St. Paul. If, on the other hand, one wants to maintain that it is, then gospel and Word of God are also bad words! Thus, the commonly asserted dichotomy between the gospel and Tradition, or between the Bible and Tradition is unbiblical itself and must be discarded by the truly biblically-minded person as (quite ironically) a corrupt tradition of men. (pp. 12-13)

Jesus uses "commandment" (singular) in the sense of apostolic tradition, as seen in other similar passages besides 2 Peter 2:21 (1 Tim 6:14; 2 Pet 3:2; 1 Jn 2:7).

Moreover, it is evident from the whole of our Lord's teaching, that in his references to Scripture he appealed to the conscience of individuals as the interpreter of Scripture, and willed them to judge of the meaning of Scripture, not by " tradition," or any other pretended authority, but by their own reason and conscience. (p. 72)

This was not the case with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, to whom He appeared (Lk 24:13-16). He listened to their messianic interpretation of the events of His own life (24:17-24). But their private judgment was wrong. Jesus rebuked them:

Luke 24:25-27 And he said to them, "O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! [26] Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?" [27] And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.

They needed authority, and the true messianic Old Testament tradition, explained by Himself to them. The same principle is shown in the story of Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch:

Acts 8:30-31, 34-35 So Philip ran to him, and heard him reading Isaiah the prophet, and asked, "Do you understand what you are reading?" [31] And he said, "How can I, unless some one guides me?" And he invited Philip to come up and sit with him.. . . [34] And the eunuch said to Philip, "About whom, pray, does the prophet say this, about himself or about some one else?" [35] Then Philip opened his mouth, and beginning with this scripture he told him the good news of Jesus.

Why didn't Philip rebuke the eunuch's Catholic-sounding plea recorded in 8:31? He didn't deny that, and didn't tell him he could understand everything by himself (according to the infallible wisdom of sola Scriptura). Rather, he authoritatively interpreted the passage for him. And it was the same in the Old Testament:

Nehemiah 8:8 And they read from the book, from the law of God, clearly; and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading.

And they alone who did so could receive him, for Tradition and the Church, in our opponents' sense of the words, were against him; (p. 72)

This wasn't the case with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, nor the Ethiopian eunuch. Goode appears to be highly selective in his use of Scripture, and to be prone to excessive claims ("always," "never," :they alone . . ."). This is bad in argumentation, because one is left in a very vulnerable spot when the opponent produces clear exceptions to a supposed universal rule.

We thus find, then, that though there is no direct testimony in the Old Testament to its perfection as the sole infallible Rule of faith to the Jews in the time of our Lord, such assuredly it was, and that for the same reason that the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament are so to us, namely, that through the uncertainty of Tradition there was nothing else which had any sufficient evidence of its being the word of God. (p. 73; my bolding)

Excellent. Goode makes the same concession with regard to the Old Testament, so that now he has expressly admitted that both Old and New Testaments do not directly state that they are the sole infallible rules of faith. I commend him for his honesty and transparency. Thus, a clear statement of the essence of sola Scriptura is absent from the entire Bible. This is manna from heaven, for the "best" defender of sola Scriptura to freely grant and concede a central plank in Catholic opposition that I have been stating for over 20 years.

What does the Protestant fall back on, then, given this crucial lack of biblical evidence for one of their two "pillars"? Well, they fall back on the weak and merely rhetorical reed of "not x." Sola Scriptura "must" be true because it ain't tradition! It's the default position. It's not Catholicism, therefore, it's true. Very compelling, isn't it? We always knew that sola Scriptura was a desperate and flimsy rationale, used to reject Catholic authority. That's how Luther and Calvin conceived it, and it has been the same ever since. But it's compelling to see a Protestant champion of it admit so openly that it has no direct biblical demonstration. I contend that -- failing that -- it is viciously circular or self-defeating:

1. It is altogether to be expected that a source that is claimed as the only infallible one, would make the claim in the first place, and not simply assume its own status as self-evident, and thus requiring interpreters to dig deep to find such a supposed teaching only indirectly or by complicated deductions.

2. Such a plain assertion is the only way that the claim can escape vicious self-contradiction:

A) There is but one infallible source of Christian authority (thus saith sola Scriptura).

B) The claim of A is either infallible or fallible.

C) In order to be infallible, by the system's own criteria, it must be in the Bible itself (A).

D) But it is not. Therefore, Protestants are relying on a fallible assertion of men (no different than any other tradition) in order to establish that a document is infallible. This makes no sense. It's thoroughly incoherent and inconsistent. Protestants rail against tradition and then turn around and are forced to use one in order to supposedly overthrow all tradition as authoritative. It's ludicrous.

E) Moreover, Protestants claim (as part and parcel of the myth of sola Scriptura) that all the most essential teachings of the faith are plainly spelled out in Scripture. They make sola Scriptura the pillar and support of their entire system of theology and authority. Obviously, then, it is a supremely important and "essential" principle to them. Therefore, by their own claims for sola Scriptura in this regard, we would fully expect that they could come up with some evidences for it from Scripture: and indeed, direct, explicit, plain ones. But Goode admits (with rather spectacular honesty) that there are none! This is, I contend, a fatal blow to the whole superstructure of sola Scriptura. Protestantism (almost unbelievably so, given all the high and sublime claims) rests entirely on an arbitrary and unbiblical tradition of men. There is no way out of the conundrum.

. . . in the time of our Lord, the Canon of the Old Testament was the sole Rule of faith to the Jews . . . (p. 73)

This is a falsehood. In fact, the Jewish canon was not finally set until after Christ. It was thought for a long time that a supposed "Council of Jamnia" held by the Jews in the late first century closed the Jewish canon, but even this hypothesis is now widely questioned, and the finality of the Jewish canon may have been as late as 200 A. D. See, e.g., "'The Old Testament of the Early Church' Revisited," by Albert C. Sundberg, Jr. See also, Wikipedia, "Council of Jamnia."

***

Published on July 01, 2012 19:11

June 29, 2012

Reply to William Goode, Contra Sola Scriptura, Part 1 (Definitions and Premises; Ezekiel 3)

See the Introduction. His words will be in blue. This installment is a response to portions of

The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice

, Volume One (1853: second edition: revised and enlarged).

See the Introduction. His words will be in blue. This installment is a response to portions of

The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice

, Volume One (1853: second edition: revised and enlarged).* * * * *

Note Goode's subtitle: "A Defence of the Catholic Doctrine That Holy Scripture Has Been, Since the Times of the Apostles, the Sole Divine Rule of Faith and Practice to the Church: Against the Dangerous Errors of . . . the Romanists, as, Particularly, That the Rule of Faith is 'Made Up of Scripture and Tradition Together,' Etc." [my bolding]

It's always good to know exactly what a person proposes to defend (matters of definition). For in-depth definitions of sola Scriptura, right from three Protestant advocates today (White, Geisler, Mathison), see the Introduction to my book, 100 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura . The idea is that neither the Church nor apostolic tradition can be regarded as infallible. Scripture is, in the Protestant view, the "sole" rule of faith.

But as I will demonstrate for the nth time, Scripture itself teaches no such thing, and I guarantee that Goode won't find it, just as other champions of the false doctrine have failed miserably in their attempt to desperately find something in the Bible to uphold the heart and essence of this man-made tradition. But it's interesting to watch them try, and thus I eagerly look forward to seeing what Goode can come up with, as the supposed "best" defender of sola Scriptura. Can his case withstand the slightest scrutiny? Read on and see!

The great fundamental principles upon which Popery rests arc precisely those here advocated, namely, (1) the interposition of a mediating priest through whose ministrations alone we can hold communion with God, and the consequent denial of the soul's "direct and independent communion" with Him, (2) the denial of the supremacy of "the written word" to the consciences of individuals, and the setting up of another "spiritual authority" in "the teaching and authority of the Church," that is, the clergy, superior to it; and (3) the making the laity of the Church dependent upon the clergy for all spiritual gifts and graces.

As it respects the first and last of these points, I must content myself here with thus pointing them out to the reader's notice. But as it respects the second, which is intimately connected with the subject of this work, there is one remark which I cannot but offer, and that is, that it is a doctrine which, whatever may be its character in other respects, is at least utterly subversive of the very foundation upon which the Reformed Church of England stands. With the doctrine of the Supremacy of Holy Scripture to the consciences of individuals, and the right of private judgment in contradistinction to "the authority of the Church," she stands or falls. For, her Reformation was effected by comparatively a few individuals acting against the authority of the Church both of the East and West, . . .

The very ground, therefore, upon which our Church stands, is that of the right of private judgment; and the question of the justice of her charge of heterodoxy against so large a portion of Christendom she leaves to the judgment of the great day. When, therefore, her ministers advocate the doctrine of "the authority of the Church" over the consciences of men, they are in fact subverting the very foundations on which their Church is built. (Preface to 1853 edition, pp. xli-xliii)

Note the viewpoint here. Church and Bible are pitted against each other: quite unlike what we find in Holy Scripture. It's the usual Protestant "either/or" dichotomous mindset. The very pillar ("stands or falls" . . . "very ground") of Protestantism is a false and unbiblical dichotomy: "the right of private judgment in contradistinction to 'the authority of the Church'" [my italics]. It's a remarkable display of fallacious tunnel-vision. I will be looking to Goode's supposed biblical proofs for these dangerous man-made innovations of the 16th century.

The word of God, however conveyed to us, binds the conscience to the reception of whatever it may deliver. Every statement that has competent evidence of its divine origin, written or unwritten, demands our faith and obedience. There is no room in such a case for doubt or inquiry. All that we have to consider is, What is delivered? And what is delivered is to be received upon the affirmation of its Divine Author. (p. 1; my bolding)

This allows for some semblance of authoritative oral tradition, which ultimately runs contrary to sola Scriptura. We shall see at length how Goode incorporates this into his opinion. My interest in this Part 1 is to document his own definitions and fundamental principles. Then we'll observe how he attempts to defend them from Scripture, insofar as he does that at all.

Moreover, if God has given us a revelation, and requires of us as individuals a reception of the truths and precepts he has revealed for our everlasting salvation, then does it especially concern us as individuals to look to the evidences of that which comes to us with the profession of being his word, that we may separate the wheat from the chaff, and not be misled in matters affecting our eternal interests. This, I say, it becomes us to do as individuals, because we are to be judged by God individually; and if we have possessed the opportunities of knowledge, it will be no plea in bar of judgment that the church or body to which we belonged taught us error, for even death may be awarded us under such circumstances, though our blood be required of those who have misled us. (See Ezekiel iii. 18, 20, &c.)

This our responsibility to God as individuals, it is most important for us to keep in view, because it shows us the indispensable necessity of ascertaining, to the satisfaction of our own minds, that it is divine testimony upon which we are relying in support of what we hold as the doctrines of Christianity. Then only are we safe, for if our reliance is placed upon anything else, we immediately lay ourselves open to error. He who embraces even a true doctrine on insufficient grounds, exposes himself to the admission of false doctrine on similar grounds. And it is more easy and pleasant to build on a false foundation than the true one, for the former has no certain limits, which the latter has. The whole superstructure of Romanism has been erected on a few false principles admitted as the foundation. And belief grounded upon a false foundation or insufficient grounds is generally but weak and wavering; and if it be shaken, true and false doctrines fall together. (pp. 2-3)

In a typically Protestant manner, Goode only sees individualistic and "private judgment" elements in the notion of authority, and completely disregards the legitimacy of God-ordained ecclesiastical authority. This is seen in his casual treatment of Ezekiel 3:18, 20. Goode thumbs his nose at the authority expressed here. It all comes down to the individual. It's true that individuals are judged in the end. We all stand before God alone, and will have to give account of our lives and actions, done with free will. But there is also authority, and we can't simply reject it out of hand. Here is the larger context of Ezekiel 3 (RSV, as throughout):

Ezekiel 3:1, 7, 11, 16-21, 27 And he said to me, "Son of man, eat what is offered to you; eat this scroll, and go, speak to the house of Israel.". . . [7] But the house of Israel will not listen to you; for they are not willing to listen to me; because all the house of Israel are of a hard forehead and of a stubborn heart.. . . [11] "And go, get you to the exiles, to your people, and say to them, `Thus says the Lord GOD'; whether they hear or refuse to hear.". . . [16] And at the end of seven days, the word of the LORD came to me: [17] "Son of man, I have made you a watchman for the house of Israel; whenever you hear a word from my mouth, you shall give them warning from me. [18] If I say to the wicked, `You shall surely die,' and you give him no warning, nor speak to warn the wicked from his wicked way, in order to save his life, that wicked man shall die in his iniquity; but his blood I will require at your hand. [19] But if you warn the wicked, and he does not turn from his wickedness, or from his wicked way, he shall die in his iniquity; but you will have saved your life. [20] Again, if a righteous man turns from his righteousness and commits iniquity, and I lay a stumbling block before him, he shall die; because you have not warned him, he shall die for his sin, and his righteous deeds which he has done shall not be remembered; but his blood I will require at your hand. [21] Nevertheless if you warn the righteous man not to sin, and he does not sin, he shall surely live, because he took warning; and you will have saved your life.". . . [27] But when I speak with you, I will open your mouth, and you shall say to them, `Thus says the Lord GOD'; he that will hear, let him hear; and he that will refuse to hear, let him refuse; for they are a rebellious house.

"Ecclesiastical" authority (highlighted in bolded portions) is all over this passage: it's the very essence of it. The prophet is God's messenger. He brings God's words and revelation and teaching. He is to be obeyed, with dire consequences if his advice isn't heeded. He's the "watchman." All of this is quite analogous to Catholic authority, but Goode can only see individualism. He sees only what he wants to see (i.e., what Protestantism has deemed relevant and important).

Nothing in the passage shows some alleged "right" of every atomistic individual to reject authority as he sees fit; to make determinations of the legitimacy of the authority or its teaching. That's all arbitrary Protestant man-made tradition: superimposed onto the Bible. The Bible teaches no such thing.

The individual Israelite is to "listen" to the prophet (3:7), "hear" his words (3:11) and not be "stubborn" (3:7) and hardhearted (3:7) and "rebellious" (3:27) when he delivers the "word of the Lord" (3:11, 16-17, 27) as God's "watchman" (3:17), who gives "warning" (3:17-21). It's the same exact notion if we substitute "bishop" or "pope" for prophet. Thus we observe a remarkable Old Testament instance of proto-Church authority, but Goode only sees individualism, save one passing concession to the blood of the flock being on Ezekiel's head if he doesn't fulfill his prophetic calling of warning them against doom and rebellion.

What does it mean for Ezekiel to be a "watchman" over Israel (Hebrew, tsaphah: Strong's word #6822)? Lutheran scholars C. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, in their massively scholarly ten-volume Commentary on the Old Testament, comment on this role of Ezekiel and its ecclesiological implications:

. . . Ezekiel is like one standing upon a watchtower (Hab. 2:1), to watch over the condition of the people, and warn them of the dangers that threaten them (Jer. 6:17; Isa. 56:10). As such, he is responsible for the souls entrusted to his charge. . . . An awfully solemn statement for all ministers of the word. (Vol. IX, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, rep. 1982, p. 59)

Apostles were the successors of the prophets, and bishops of the apostles. Hence St. Paul warned his followers to exercise their grave responsibilities, similarly to what we see in Ezekiel:

Acts 20:28 Take heed to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God which he obtained with the blood of his own Son.

And belief grounded upon a false foundation or insufficient grounds is generally but weak and wavering . . . (p. 3)

I couldn't agree more!

In matters of faith, therefore, the divine rule is our sole authoritative rule; in matters of practice there maybe added to those which are prescribed by the divine rule, by the authority which Christ has left with his church for the direction of its rites and services, such as are necessary to the maintenance of peace and order. (p. 5)

This is a helpful distinction; showing more nuance than some defenders of sola Scriptura (typical of the wider latitude and freedom of thought of Anglicanism). I would note in passing, however, that this tolerance of practice and ecclesiastical tradition in this sub-doctrinal respect, is not consistently granted to the Catholic Church. So, for example, little quarter is given to us if we distribute communion in one form only (as traditionally), or require priestly celibacy: both practices and not dogmas.

All of a sudden, wicked "Rome" is not allowed to make those determinations, and in doing so is exercising arbitrary and indefensible raw power; whereas saintly, sanctified, all-wise Canterbury is freely granted this prerogative. The double standard is (no doubt) never even noticed . . . Such is the fruit of prejudice upon consistent rational thought.

Both for the fact that Scripture is the word of God, and for the correctness of the doctrines we deduce from Scripture, we carefully give both the child and the ignorant man all the proofs their condition renders possible; . . . (p. 6)

Excellent! I'll be perusing these "proofs" very carefully to see if they hold water, as to the notion of sola Scriptura.

. . . while the Romanist demands belief on the authority of what he calls the church, that is, on grounds which the past history and present state of the church show to be a nullity.(p. 6)

No!; we ground it on the testimony of Scripture itself on the authority of the Church (an example of which we saw above, in Ezekiel 3 . . . ). If Scripture teaches about the existence an authoritative and infallible Church, then there is such a thing, and we bow and submit to its authority on the testimony of Scripture (and sola Scriptura crumbles). Which church this described scriptural church is, today, is, of course, a separate issue that has to be determined, on historical and rational grounds.

We also ground the notion, additionally, on the universal testimony of the Church fathers, just as Goode unsuccessfully attempts to base the legitimacy and truthfulness of sola Scriptura on their testimony as well. But patristic testimony is beyond our present purview. Both sides appeal to Scripture. The question is which has a better, more consistent, plausible case: taking into account all of Scripture: not just carefully selected "prooftexts." I'm focused like a laser beam on those arguments, in this critique.

We have, then, to determine the limits of the divine revelation we can ascertain to have come down to us from them.

Here, again, it is generally admitted, that the most sacred record of this revelation is to be found in the Holy Scriptures.

But it cannot be denied, that when the apostles were delivering to men that divine revelation with which they were charged, they delivered it by word of mouth as well as in the writings that have come down to us, and that they first delivered it orally, and afterwards penned the writings they have left us. The question, then, for our determination is this, Whether we have any record or witness of their oral teaching, such as can be received by us as a divine revelation supplementary to, and interpretative of, the writings they have left us. (p. 7)

Good presentation of the true issues at stake. All proponents of sola Scriptura have to grapple with the question of the relation of authoritative apostolic oral pronouncements and Scripture. If any of these oral teachings were preserved alongside Scripture, without particular reference in the latter (or at least not explicit reference), then it seems that sola Scriptura, as defined, cannot stand.

The Protestant defender has to find some way to argue that all such beliefs made their way into Scripture ("inscripturation") and that none whatsoever survived apart from Scripture. That's pretty difficult to do, and I have as yet seen no biblical indication of such an idea. I contend that it is yet another man-made tradition, arbitrarily invented "on the spot" out of the need to bolster the larger man-made tradition of sola Scriptura as a principle of authority.

We hold also that the consent of many of the most able and pious ecclesiastical writers of antiquity (and what is called catholic consent is nothing more than this) in favour of any particular view of divine truth, is an argument of great force in defence of that view, not from the improbable possibility of such consent having been derived from the oral teaching of the apostles, but rather from the probable evidence afforded by such consent, . . .

Further, we do not deny, that any man who differs from the true catholic church of Christ in fundamental points must be in fatal error, and that the faith of that church in such points must in all ages be the same; we do not deny, that there may have been fuller communications made by the apostles to some of their first followers on some points than we find in the Scriptures they have left us; we do not deny the possibility that interpretations of Scripture brought to us through the Fathers may have originally emanated from the apostles; we do not deny, but on the contrary firmly maintain, that the true orthodox faith, in at least all fundamental points, is to be found in the writings of the primitive Fathers, and therefore that it is very necessary, as a matter of evidence, that in all such points our faith be such as can find some testimony for it in their writings: . . . (p. 19)

Good statement of commonly held elements . . .

Speculative arguments have been adduced on the question on both sides, which, however plausible they may appear to the general reader, are far from being trustworthy. Thus, the advocates for the exclusive authority of the Holy Scriptures have often urged, that the Scriptures being given by God for the instruction of mankind in religion, they must be perfect for the accomplishment of the purpose for which they were given, and therefore must contain all that has been revealed for that purpose. But it does not follow that, because the Scriptures were given for that purpose, they are necessarily all that has been given. (p. 20)

True and helpful qualification . . .

The great object of the following work, then, is to demonstrate, . . . that there is nothing of which we have sufficient evidence that it is Divine or inspired testimony but the Holy Scripture; and consequently that the Holy Scripture is our sole and exclusive Divine Rule of faith and practice. (p. 21)

There is some clever wordplay here and failed attempted parallelism of non-equivalent notions. Goode confuses inspired works (Scripture) with infallible or binding authority, as if the latter is not a present and necessary category, or as if the only authority we can have must be inspired ("God-breathed" or theopneustos). Catholics and Protestants agree that Scripture is inspired. That is not where the dispute lies; therefore all arguments devoted to proving that are entirely beside the point in the debate over the rule of faith.

The problem lies in assuming what one needs to prove. It is illogical and not reasonably demonstrated that the only authority must be inspired. Therefore, Goode has no basis for moving from stating that Scripture is inspired, to concluding, "consequently that the Holy Scripture is our sole and exclusive Divine Rule of faith and practice." He merely assumes that all carriers of the rule of faith are inspired as well as infallible. But there is also such a thing as an infallible Church or tradition that is not inspired, yet still has binding and (possibly) infallible authority. Goode's task is to disprove the latter categories, and from Scripture; rather than to casually assume -- with no argument or proof -- that they are impermissible aspects of the rule of faith.

We shall see that much of the argumentation in favor of sola Scriptura is simply circular argument or begging the question; assuming what one needs to prove. This is always the case; I've never seen a single exception, in my twenty years of active Catholic apologetics.

* * *

Published on June 29, 2012 13:49

June 27, 2012

Goode Defense of Sola Scriptura the Best? We Shall Examine It and See!

In my eternal and perpetually disappointing search for Protestants who actually try to make a serious rational defense of the Protestant doctrine of sola Scriptura from Scripture itself, I have now (almost desperate to find something; anything!) arrived at William Goode (1801-1868): an English evangelical Anglican. His relevant work is, The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice , originally two volumes in 1842, and then revised and enlarged to three volumes in 1853. I have located them online (Vol. 1 / Vol. I [alt] / Vol. II / Vol. III), and of course they are in the public domain.

Recently, I was crushed yet again when I discovered that David T. King, despite the title of his book ( A Biblical Defense of the Reformation Principle of Sola Scriptura ), did not make such a case from Scripture, apart from a few (very weakly argued) instances, which I replied to.

I've already done an 18-part reply to the work of William Whitaker, a highly-touted 16th century advocate of sola Scriptura. Possibly we have a book in the offing at some future date: my replies to both Whitaker and Goode. As we would expect, Goode, like Whitaker -- both Protestant "champions" over against the lowly, wicked papists -- , receives glowing accolades from today's Protestants (particularly the fringe anti-Catholic ones) who follow sola Scriptura, and/or seek to justify it themselves:

But of all the treatments dealing with sola Scriptura, the work of William Goode, The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice, has never been surpassed. (David T. King, ibid. [2001], p. 17)

. . . classical works on . . . sola scriptura, such as William Whitaker’s late 16th century classic, Disputations on Holy Scripture, or William Goode’s mid 19th century work, Divine Rule of Faith and Practice. (James White, blog post, 8-18-10)

I heartily commend to your reading William Goode's The Divine Rule of Faith and Practice . . . a genuinely scholarly work on sola scriptura. . . . Everywhere I turn, William Goode is referenced in the literature. (D. Phillip Veitch, Anglican message board, 3-20-09)

I will be examining these volumes specifically to see how Goode makes his case from Scripture . That is my sole interest. I will offer up rebuttals to any significant biblical argument that actually deals with the heart and stated definition or essence of sola Scriptura: the notion that only Scripture is the sole infallible guide for the Christian: to the exclusion of an infallible tradition or infallible Church (the latter two notions both accepted by Catholics). I have no interest in arguments for inspiration or material sufficiency or other relative side issues, because Catholics already agree with those.

Future installments of this series will be listed below:

* * *

Published on June 27, 2012 16:32

June 26, 2012

Rebuttal of David T. King's Defense of Sola Scriptura from Romans 16:15-16 and 2 Timothy 3:16-17

.

.

Pastor King's words from his book will be in blue.

* * * * *

My normative policy of time-management or stewardship of my time under God, and maintenance of sanity for nearly five years now is to refuse to waste time debating theology with the small fringe group of anti-Catholic Protestants (i.e., those who deny that Catholicism as a system of theology and spirituality is Christian, and who claim that in order to be a good Christian, one must reject quite a few tenets of Catholicism). I do, however, make exceptions on rare occasions.

I have continued to interact with historic Protestant anti-Catholic works, and I did, e.g., in the case of William Whitaker, a prominent 16th century advocate of sola Scriptura (18-part reply). I also have lots of material (including two books) concerning major Protestant figures Luther, Calvin, Chemnitz, Zwingli, Bullinger, and others.

The self-published, three-volume set (one / two / three) on sola Scriptura by David T. King and William Webster (2001) is clearly relevant in relationship to my current book, 100 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura . Volume One (A Biblical Defense of the Reformation Principle of Sola Scriptura) is virtually a polar opposite of my title. I say the Bible opposes the notion; he maintains that it supports it. That makes for some good debate (and as anyone who knows me is aware, I immensely enjoy debate). It's stimulating and fun, and educational, all at the same time.

I had originally intended to do a multi-part rebuttal, as I did with Whitaker, but I have discovered that King scarcely makes any arguments from the Bible, for the purpose of establishing sola Scriptura proper; thus this will be my sole reply. I will have to seek out another work that actually tries to prove the doctrine from Scripture. That is what interests me: not more circular logic and man-made traditions spewed endlessly.

Pastor David T. King is a Presbyterian, and graduate of Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi. He is pastor of Christ Presbyterian Church (OPC) in Elkton, Maryland, and was formerly affiliated with PCA.

Unfortunately, most of the books that deal with this topic in the greatest depth (e.g., others by Keith A. Mathison, Bishop "Dr." James R. White, and R. C. Sproul), come from anti-Catholics. Be that as it may, we can handily refute these arguments from a Catholic and thoroughly biblical perspective.

Now onto King's few biblical arguments in favor of sola Scriptura:

If unwritten tradition was . . . intended to function perpetually as an authoritative norm alongside Scripture, why did Paul fail to mention such a concept when speaking of 'the revelation of the mystery kept secret since the world began?' (p. 44) [see Rom 16:25-26]

He doesn't have to, anymore than he can write the following extended treatment of many important aspects of the Christian life without ever mentioning Scripture:

I stated along these lines in my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism (2003):