Chris Baty's Blog, page 127

March 28, 2017

"Look at the people who inspire you, and choose one trait to take on in your own writing. It doesn’t..."

Reach out and pick the first gleaming fruit off their tree—perhaps, their love of description, their talent for playful banter, or even their deft weaving in of beloved pop culture.

See if you can focus on that skill as you prepare to write. See how you can work that gift yourself, or how you might have already been displaying your own talents with it without even thinking about it.”

-

Karuna Riazi is an online diversity advocate, essayist, and overwhelmed undergrad senior at Hofstra University. Her debut novel, The Gauntlet, is out today!

Your Camp Care Package is brought to you in partnership with We Need Diverse Books. Sign up to receive more Camp Care Packages at campnanowrimo.org

March 27, 2017

Camp NaNoWriMo

Camp NaNoWriMo is less than a week away! Have you created your writing project yet?

Each Camp session, we’re joined by published authors who act as “counselors” in your Camp Messages inbox as well as on the blog. Follow this link to check out our awesome lineup of Counselors who will be dispensing words of wisdom, advice, and encouragement to all our NaNo Campers this April. You’ll also find an archive of past Camp Counselor advice and both noveling and non-novel writing project resources for your own personal writing retreat.

Let’s get ready to write, Campers!

March 24, 2017

3 Important Things to Know When Writing a Graphic Novel

We’re getting ready for Camp NaNoWriMo this April! This month, we’re talking to Wrimos who are using the Camp format to work on non-novel projects. Today, participant Dawn Eastpoint shares some of the most important things to keep in mind when tackling a graphic novel:

Graphic novel: the union of the written word and sequential art. A medium that has recently come into mainstream appreciation, inspiring Creatives young and old.

There are three things I suggest you remember when you choose to create a graphic novel:

1. Page real estate is expensive.The number of words needed is a fraction of what’s in a novel or a script, but that lack of written communication needs to be compensated with clear, visual scenes to tell the story.

When do you show, and when do you tell? Too much of one or the other will result in a muddled sequence that frustrates your readers. Your graphic novel is 100% still-motion entertainment, so don’t bog it down with blocks of words or unnecessary pictures that mess with the pacing.

If your script or story says, “a tear runs down her cheek as sorrow overwhelms her,” don’t paste that word wall in as exposition. Show it happening. If your reader can see it then there’s no need to clutter the scene with narration.

Whether your chapter is 10 pages or 40 pages long, each one must count. In this limited space you have to convince your audience to love your world and your characters. You have to spin a tale of development, twists, subtext, and history with as few words and panels as possible.

2. Don’t overthink it.

2. Don’t overthink it.Grab a piece of paper, a sticky note, open a new document in your preferred word program, or use a crayon on whatever happens to be nearby.

Start writing.

Then do the same thing when you’re ready to draw. Take a marker to cardboard if that’s what works. And it doesn’t matter if you write or draw first, or do both simultaneously.

Don’t worry about details yet. Don’t know what anyone looks like? That’s cool. The dialogue isn’t developed yet? That’s cool, too. Can’t figure out what the bad guy is up to because there’s no backstory? It can wait.

This is why the next part is important.

3. Stick figures and blobs are your friends.

3. Stick figures and blobs are your friends.Visual storytelling–whether a 4-panel strip, an animated movie, or a graphic novel–starts with the “roughs.” They stay the focus for 80% of the work’s creation process.

Roughs are what they sound like: they’re the unrefined drawings that more often than not look like crap. Love your roughs, they are as important as the final product.

This stage is the easiest phase to see what works and what doesn’t, and the least amount of work to change or do multiple versions of. This process of creating and refining is called pre-production in most fields. Note the “pre.”

Properly executed pre-production work equals fast and smooth production right into final production with minimal changes. That means major savings in time, money, and sanity. Mostly sanity.

Do as many rounds of pre-productions as you need until the pages tell your story. Use your stick figures and blobs until you find the composition that works, the expressions that fit, the dialogue that says what needs to be said and still manages to work with the panels. Add pages, subtract them, add scenes and subtract them.

Save your sanity and do it all with stick figures and blobs. Add more details once you’re sure of a panel. Clean lines can wait. Color/shading/highlights can definitely wait.

You know what? There’s one more important thing:

4. Nothing is perfect!You have a deadline. Get it done and move on. You’ll love your work in the end.

Dawn Eastpoint is an illustrator, animator, Jack-of-All-Arts, writer, and avid lover of manga, anime, and cute things. She’s also mother to a rescue turtle, a yellow-eared slider named Gimli because he’s short, round, and can’t jump. She suffers from several medical conditions but doesn’t let them stop her from creating! Her muse won’t shut up and leave her alone, anyway. Dawn can be bribed with Starbucks, baby animals, and food things. You can visit her Patreon, DeviantArt, and Archive of Our Own pages.

March 22, 2017

5 Ways to World-Build

We’re getting ready for Camp NaNoWriMo this April! Camp is a great way to expand your writing style or work on a different type of project than you normally do. Today, participant VicJ Wizard discusses some of the ways that detailed world-building can add to your novel or writing project:

Writing is hard.

As a writer I can say I’ve had amazing ideas and even written them down (when possible, that is; of course these things never come to you at the right moment) but I have always struggled to continue on with the characters and worlds I created in those moments. This is where world-building becomes exciting and can help your ideas become clearer. World building can be extremely detailed–in fact, I bet some authors have spent more time building their worlds than writing their works. However, there are a few basics required to build any large-scale world in writing.

1. Cross-reference your details.I am currently so deep in my world-building that I am creating maps, histories for each of the races in my world, hierarchies, religions, and languages. It gets a bit overwhelming, especially when all the different categories cross over, which leads you down lots of different trails and never lets you fully complete one.

A great example is the pickle I am in right now: I have sketched out the history and written a historical timeline for each race represented in my novel. My hierarchy is done, and I have chosen the types of religions each group might have based on my ideas for what I want their people to be like. However, without having developed any languages, I have no consistent way of naming things like the deities of those religions or the time units each group might use (such as time, day, and month names). Looking at the fuller picture of the world I’ve built, I know I now need to crack down and create the languages.

2. Create a backstory.For a large-scale story, you should know the history of your world at least 200 years prior to your story line.

That sounds like a lot of effort! Why do I need this?

Because your characters are going to know this information. They will be familiar with the recent history of their world, and so should you.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking you are going to tell your readers those 200 years worth of background story. It might never even reach the pages of your work. But your characters need to know–and you as the writer need to know–just in case it comes up in conversation, or one of your scenes is based at a historic site, or somewhere that makes at least one of your characters think of a past event.

This step is also essential in setting up your story; past events can give you reasons and ideas for events that may happen to or around your characters.

3. Draw a map.Let’s face it: readers (myself included) love books with maps! Also, if the map is only in your head, you can easily forget which way is what and where you are going. Even if you can’t draw at all, you can still put some lines and dots on a page to make a basic map.

4. Create a social structure.Every world needs a hierarchy, social structure, or way that different groups of people live and interact together. You don’t need to build a very in-depth one for your world unless it’s important in your story line, but you still need one there. Is it a fantasy world with a king and queen, an emperor or empress, or is your world modern with government, political parties, and corporations? Whatever it is you need to know, your world needs to have structure if it’s going to be realistic enough for your readers to get immersed in it.

5. Think about the basics.Most societies have a language, calendar system, and some kind of belief system. If you don’t require such in-depth information for these, I’d suggest very basic ideas here at the least.

You can pick a name for beliefs or religions. What kind of belief system is in place? Is there a god or a goddess associated with each religion? Unless religion plays a huge role in your story, you can get away with basic information here.

When thinking about the languages in your story, decide if you will focus on one, or have characters speaking or writing different languages. If your main character understands the language that’s being spoken, they can usually just translate it. But if it’s written down or plays a big part in the story, you may need to think more deeply about what that other language looks or sounds like.

Having a calendar is a little more needed than the above two. What holidays does your world celebrate? How long are the days/weeks/months/years? What is the moon cycle? Of course you can always use our own, and change names of holidays if you don’t want to get into this aspect of the world-building, but some kind of calendar is required if you want to set your timeline and events out properly.

There are a great deal of websites and books out there that can help you build each of these aspects and tailor them to your world. Remember that if the question doesn’t suit your world, you can always change it slightly to be what you need!

Vicki has a Bachelor in English Literature (Honours), and is the founder of the first Literature and Writing Club at her university. She is also a writer, has a small blog, and is published in the university magazine and blog. She won her first NaNoWriMo in 2015 and is working towards extending it into a full length novel. Vicki has a vivid imagination, is addicted to TV, and loves reading, playing, and watching video games.

Top photo by Flickr user David Higgs.

March 20, 2017

Working Through the Worry: The Miracle of Composing a Collaborative Novel

In addition to the main NaNoWriMo and Camp events each year, NaNoWriMo provides free creative writing resources to educators and young participants around the world through our Young Writers Program. Today, educator Nick Kleese shares the success story of his class:

The first tears of our class novel came on the second day of writing. I remember: I was kneeling beside a desk, squinting at the laptop screen bright with the white glare of the early morning sun, attempting to guide a student through writer’s block. “What else could there be to write about?” the student demanded, nearly shaking with frustration.

I rambled for a moment, brainstorming through my own tired, foggy thoughts, before noticing the heaving beside me. I looked up from the screen and saw a face flushing red and eyes swimming with a writerly angst that was both very real and very unexpected.

Now, this is my first year teaching high school, and I’ve become good friends with anxiety and fear and their cousin: that feeling of I-have-no-idea-what-I’m-doing. I’m good friends, too, associatively, with existential despair.

Regardless, I have hope. I’ve gone back to my hometown, and I am comforted by its familiar, sprawling cornfields and calloused hands. As a farm kid, I see myself in my students: some, I know, will attend four year schools and then scatter. Many will opt for technical or vocational two-year programs to become certified welders, truckers, cosmetologists, administrative assistants. Others still will head straight to work, which, in my hometown, is a decision celebrated for its innate devotion to the art of work itself. Despite the initial emotional upheaval, I believed NaNoWriMo’s tangible–albeit lofty–goal would well suit my students’ pragmatism. I knew I could lean on my students’ proud diligence to get them through writing an entire novel–even if they believed writing wasn’t, as they put it politely, for them.

Our process, depending on the observer’s disposition and pedagogical beliefs, was either vibrant and bustling, or chaotic and terrifying. We spent the first few days frantically studying novel structure and character development, then two more days planning our own. I’d dug out a long, dusty scroll of white paper from the school’s storage closet and had it unrolled across the white board. We tacked it up, as a class, and drew Freytag’s Triangle long and uneven across it.

“Okay,” I said, turning to my apprehensive class standing with me. “What should we write?”

My students understood that, frankly, I had no idea how the novel would turn out. In my mind, we would plot the story in detail on the scroll, then divide it into twenty-some parts–one for each student to write. The students would meet with those whose parts came directly before and after theirs to discuss transition points, contemplate continuity issues, and debate the project’s potential to flop. My room became a hodgepodge of notes and diagrams and character sketches and spilled coffee grounds and chatting students who were wary, confused, frazzled, but willing to work.

“By positioning myself at desk-level, student level, the project became less about learning concepts and more about practicing, collaborating, and creating.”We worked nearly every day for a month. I’d write, too. My youth and scrawny frame helped me blend in–so much so that when the Dean of Students would enter with a clipboard of truancies, he’d stop, glance around, and ask, “Where’s Kleese?” The students would point me out among the desks, hunched over, typing away, perhaps only distinguishable from them by my coffee-spotted earthenware mug and tie.

By positioning myself at desk-level, student level, the project became less about learning concepts and more about practicing, collaborating, and creating. Voices would call across the room, directed at a peer or me or everyone, asking: “How do I punctuate dialogue?” “What if I want the ‘he said’ to come before the words?” “Where do I break paragraphs?” “What’s a synonym for ‘blue?’” Sometimes I would answer, and sometimes a student would beat me to a response. In this way, the novel not only forced students to ask authentic, necessary questions as writers (ones that I could only dream of being asked otherwise), but it also revealed writing’s vastly different meanings and challenges for each individual student. Some struggled to punctuate a sentence. Some were behind, as they worked a full time job outside of school. Others volunteered to spend their class time helping others. All wanted deeply to write the damn thing and to make it good.

Despite these differences, however, I would, at times, find my attention drifting during class, away from the novel and its hiccups and its chaos to the miracle around me. Everyday, in face of the difficulties and drama and anxieties that exist outside of my classroom, students showed up to write. Farm boys and doctor’s daughters, athletes and English Learners, artists and mechanics all sweat and cried (no bleeding, that I’m aware of) over a story about a teenager who redefines home. In a year marked by division and worry and uncertainty, I found affirmation in the spectacle manifesting daily in my classroom.

We wrote the damn novel. And, because we did, I have hope.

Nick Kleese is a first-year Creative Writing teacher at his alma mater of Washington High School in Washington, IA, where he also serves as the head Speech coach. If not in the classroom, you can find him helping on his family’s farm or running the crushed limestone trails of the Southeast Iowa prairie. He is currently working to transform his youthful naiveté into lifelong, sustainable optimism.

Washington High School is the local high school serving the farming community of Washington, Iowa, whose vision is to “prepare students for lifelong learning” by engaging, inspiring, and empowering every student.

Top photo by Flicker user Informedmag.

March 17, 2017

Short Stories: Don’t Underestimate Your Writing

We’re getting ready for Camp NaNoWriMo this April! This month, we’re talking to Wrimos who are using the Camp format to work on non-novel projects. Today, participant Paulinette Quirindongo dives into some of the advantages of short story writing:

The novel and the story are as old as your great-grand-ancestor, yet not as old as the art of storytelling itself. Both writing forms are centuries old: the modern form of the short story dating back from the 19th century (although its traditions in oral storytelling and fables are much older), and the novel as it is recognizable today from the 15th century. These have become the two main forms of fiction writing that have been used to question, to understand, criticize and interpret the world we live in.

Writing a short story or a novel is like creating a new world from paper and ink, then plastering it on to that little new planet that is waiting to be set free from the farthest depths of the universe: our consciousness. Many people seem to think this is a simple thing to do, but we writers we know that is not an easy job.

My first writing experience was in ninth grade. I was frustrated with the disappointing ending of my favorite series and, based on that frustration, began writing. Today I cannot stop feeling embarrassed about what I wrote in those three long notebooks, one for each year that I wrote. The three main reasons for my embarrassment are: (1) My story does not have one main topic, but infinite topics, (2) it has no coherence, and (3) I underestimated it. (The last one I will explain further on.)

In some ways, the art of writing a novel may seem easier than writing a short story, because in a novel you have some liberty when it comes to plot and subplots, characters, symbols, and settings. Short stories, on the other hand, typically have one plot, one setting, few characters, one or two symbols. Yet they still must have substance enough to have readers become invested in the characters and outcome of your story.

Anyone can write a short story, a novel, a poem, or short fiction, but each form of story should still be carefully crafted. Writing is not just putting words on paper, (although that is an essential part); is about concentration, preparation, and consistency.

“My advice to any of you that are planning to start a new writing form is: try it, explore it, savor it, and love it, but above all do not underestimate your writing and the type of writing form that you choose.”It can be easy to underestimate any kind of genre when when the stakes don’t seem as high. When it comes to short stories, people tend to think that because it is a small tale, you don’t have to care as much about plot, setting, coherence, and substance. On the other hand, the main reason people underestimate novel-writing is thinking that they can put everything into the story without a care in the world how it goes together. But with both formats, you need to ask yourself: is this bit necessary? Does it serve a purpose within the plot? How does it fit in?

A short story, yes, it must be short; but like a novel, it still needs substance, a plot, a meaning. In other words, it should still give the readers goosebumps when reading that new creation plastered into that 300 or 1,000 word count.

My advice to any of you that are planning to start a new writing form is: try it, explore it, savor it, and love it, but above all do not underestimate your writing and the type of writing form that you choose. It’s ok to be afraid of making mistakes, to feel insecure, and to think that your first draft seems bland or that that brilliant idea you had now seems dumb. It’s ok to feel like that, but do not let those demons stop you. It takes effort to try to keep to the point as we get ourselves lost in that small biosphere of writing, but it takes greater effort to face our fears and prove our doubts wrong.

Paulinette Quirindongo is a young writer from the island of Puerto Rico. She knows eight languages and is studying for her Master’s degree in History. She has participated in NaNoWriMo for the years 2013, 2014, and 2015, and hopes to participate again this year. She published her first novel in 2015 and is currently working on her second novel. She published one short story in the zinc magazine MicroCuento, created by students from the university she studied. Check out her website or preview her novel.

Top photo by Flickr user Jenn and Tony Bot.

March 15, 2017

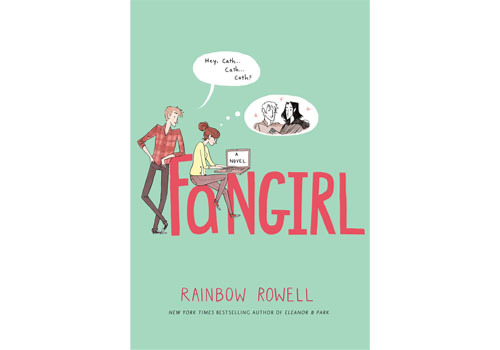

Books That Changed My Life: How “Fangirl” Brought a Fangirl Back to Life

In this blog series, NaNoWriMo participants can share their experiences with books that have changed their writing–and their world-views–for the better. Today, NaNoWriMo participant Monique shares her thoughts on a book that helped her embrace her voice and rediscover joy in writing:

It’s a secret/not-so-secret amongst my friends that I write fanfiction.

It all started way back in middle school when a friend showed me fanfiction.net and told me how all these writers bend and borrow from their favorite work to create something new. I didn’t think too much of the website at the time, but when a certain anime phase hit me like a truck (or, shall I say, like a ninja kick to the face), I wanted in on the fanfiction business. It was the perfect place for me to practice writing and to learn how to handle criticism and feedback. Gotta love the internet.

That phase leveled off around high school and my first two years of college. I didn’t get back into writing, but I got back into watching anime around the fall semester my junior year, which just so happened to be around the release of Fangirl, a book that practically threw me back into the business that made me love writing so much more.

The author of Fangirl, Rainbow Rowell, has said that the book was a product of her own NaNoWriMo adventures. This book was the one novel that drove me to open up a doc and start writing fanfiction non-stop over the next several days after finishing it.

Those days were surreal.

“Fangirl was the ultimate bridge that connected me back to writing.”

“Fangirl was the ultimate bridge that connected me back to writing.”If you aren’t familiar with any of Rowell’s work, I highly suggest checking her out. I read Eleanor & Park (and had to take some time to heal my heart) before reading Fangirl. Obviously, I was thrilled to read about a girl who writes fanfiction and was so immersed in her work. It took me back to the days when I wrote on fanfiction.net and updated my work every week for my “followers,” though I absolutely did not have as many as Cath, the protagonist of the book.

Speaking of whom, Cath’s power of writing fanfiction was not the only part of her I could relate to. The way Rowell captures her social anxiety and the ever-growing distance between her and her twin sister, Wren, also hit close to home. For example, I’d much rather attempt to work out at home alone than in a gym–which seems to be the realm of more social and graceful butterflies like my younger sister. I still have a thousand reservations about going to the gym, even though I know it’s a great choice for my health.

Gym anxieties and siblings aside, Fangirl was the ultimate bridge that connected me back to writing. College–and pressures of what to do after college–kept me from finding the same joy in writing assignments. If I did, it wasn’t good in my eyes and words were left scrapped in a deleted document. But upon closing the book and lying in my bed for a solid few minutes, I knew that my fingers were craving to do something that they hadn’t done for a long time.

I could go on about every single element I loved about Fangirl, but Cath’s devotion to fanfiction and the craft of writing was the motivation I so strongly needed after years of being bogged down. It’s part of the reason why I took screenwriting and creative writing during my last year of undergrad. It’s definitely the reason why I’m still writing fanfiction today.

Professor Piper, Cath’s fiction writing instructor, asks her class why they write. In some way, Cath’s answer is right; “I drop off from the real world, away from responsibilities and obligations that make my head spin. I disappear.”

That’s not the main reason why I write, though. My answer is simple: I love it. I love that writing will always and forever be my outlet. I love that I can work wonders with words and write something oh-so-pleasing for readers and for myself. I love that no matter how much I endure writer’s blocks and slumps, I can find myself coming back to doing it.

Now, to find someone who loves me like a certain character (whose name I won’t reveal because spoilers) loves Cath…well. At least writing is there for me.

Enough about me. Why do you write?

When she’s not pursuing a master’s degree in a field completely unrelated to fiction-writing, Monique, or Momo for short, caters to anime watchers and manga readers through fanfiction and all-caps discussions of alternate universes. She won her first Camp NaNo in 2014 and continues to participate in NaNo events whenever she’s able to. In the meantime, she continues to learn, improve, and most importantly, write. You can find Momo on Tumblr or Twitter.

Icon commissioned by Jazzmin.

Top photo by Flickr user Ida.

March 13, 2017

Writing Behind Bars

NaNoWriMo has found its way into elementary classrooms and universities, foreign countries and hometowns. But did you know that NaNoWriMo also has a place in the prison system? Dedicated volunteers like participant and author Neal Lemery help give inmates an opportunity to voice their stories:

Much of my writing inspiration comes from the stories of the young men I visit in the nearby youth prison. I tutor in their garden and help youth in their transition to parole with my guitar, cribbage board, and endless cups of canteen coffee.

Several of the young men joined me in the NaNoWriMo challenge this year, inspired by their English teacher and by my actually producing a real book out of last year’s efforts.

“We figured if you could do it, we could, too,” one youth told me.

Writing in prison? I wondered how anyone could manage it. The prison has twenty-five young men sleeping in each dorm room filled with bunk beds, a living area with a blaring TV, video games beeping and chirping, and the voices of two dozen exuberant teenagers. Meal times are marked by marches to a cafeteria two buildings away, through the often rain-drenched Oregon coast winter weather.

They often write for an hour or two after bedtime, even managing to borrow a flashlight from a guard after lights out. After all, they are earning English class credit.

Writing in full NaNoWriMo mode challenges me, even on the days when the Muse is happy and full of words for me to tap into my laptop. I’m spoiled: with my nice, comfy chair by the fire; a never-empty cup of tea; and nearby snacks in my nice, peaceful house. I clatter away, continually checking my daily word count. Still, I grumped to my unsympathetic wife about the pressure of 1,600 words every stinking day. November is a long month.

Wait a minute, I thought. What am I whining about? I’m not doing this in prison, with a stubby pencil and a cheap spiral notebook.

During the month, the students and I checked in with each other, with the usual grumps: losing sight of our plots, our characters petering out with a lack of adventures or personality quirks, and the annoyance of no time to go back and edit our daily blood-lettings on paper. My writing buddies kept pace with me, comparing word counts and plot twists twice a week when I visited. My fellow writing prisoners kept me filled in on their writing, needling me with all their youthful creative writing energy.

One guy was on work crew the whole month, cutting firewood and planting trees during the wettest November in twenty years.

“Oh, I wrote in the van, when we had our breaks and lunch,” he bragged. “I got most of my words done out there. But my notebook got a little soggy.” He grinned–a true NaNoWriMo martyr. Other guys wrote on their bunks, scrunched up and leaning against the metal frames, sitting on thin mattresses, writing their hearts out, making the word count.

At the end of the month, I was greeted with elation: “I won, I won!” the wood-cutting, tree-planting author shouted at me. “I got my 50,000 words, and I’m already thinking of the sequel for next November.”

I bought two NaNoWriMo winner T-shirts last year. I’ll wear mine with pride, but I know when he puts his on, his smile will be a lot bigger, and the T-shirt certainly more deserving.

Neal Lemery is the author of Mentoring Boys to Men: Climbing Their Own Mountains, and Homegrown Tomatoes: Essays and Musings From My Garden. He’s completed NaNoWriMo the past two years, with his 2016 efforts producing a novel. He’s a retired judge living on the Oregon coast.

Top photo by Flickr user Miranda Ward.

March 10, 2017

Camp NaNoWriMo: Breaking the Rules of Genre

We’re getting ready for Camp NaNoWriMo this April! Camp is a great way to expand your writing style or work on a different type of project than you normally do. Today, author Laura Goodin delves into the history of genre–and shows that you don’t have to put a label on your writing to make it work:

You know them, you love them, you use them. They’re comfortable and satisfying. They communicate a lot of meaning and background efficiently. And they’re something you share with thousands, even millions, of kindred spirits. They’re tropes, genre conventions, the rules for how a story should go.

Popular fiction, and speculative fiction in particular, began to be sorted into categories beginning around the late 1920s. Various pulp magazines and publishers began to go after the loyalty of specific readerships by giving them more and more of what they had shown (with their dollars) that they liked.

Three early examples were Weird Tales, founded in 1923 and specializing in sword-and-sorcery stories such as Robert E. Howard’s “Conan the Barbarian” tales; Amazing Stories, founded in 1926 and including a broader range of fantasy stories; and Astounding, John W. Campbell Jr.’s successful science-fiction pulp.

As this system rigidified, driven by publishers’ economic imperatives, it revealed a number of benefits to the other members of the writing ecosystem as well. Fans could quickly and easily gravitate toward the types of stories they loved, and could use these shared interests to form genuinely welcoming and fulfilling communities–in other words, fandoms. Booksellers could guide fans to what they loved, and make buying decisions based on predictable and consistent demand. And writers who worked within the expectations of a particular genre not only had a better chance at a reliable income, but might actually enjoy the challenge of making good art within those frameworks.

Because these benefits tend to reinforce each other, the expectations we have of a particular genre have become virtually inescapable. If I tell you that a story has a desert and a horse and a cowboy and a train robbery, you will immediately decide it’s a western. But what if the horse starts talking? Suddenly the story has become something else. But what? Which shelf does it go on?

Many, many writers are increasingly experimenting with mashups and genre-bending, in both published and fan fiction. They’re combining zombies and Jane Austen, landing Star Trek characters at Hogwarts, making ghosts from the future fall in love with Victorian-era jungle explorers. (I made that last one up, but it wouldn’t surprise me if someone had beaten me to it. If it intrigues you, feel free to use it.) This may feel like an innovation, but in fact it’s a return to our roots as writers of fiction that aims to enchant, astonish, and unnerve.

If you have the chance to read some of the “romance”* fiction of the mid- to late 1800s (and because you can get lots of it for free on Project Gutenberg, what’s stopping you?), you will find a heady and glorious chaos of genres, tropes, writing styles, character types, and themes. Writers couldn’t follow “the rules” because there were no rules yet. And that made for some superb and enthralling writing.

So when you sit down to write, maybe you’ll find it’s time to shake yourself up a bit. Time to break the rules. Time to keep asking yourself, “What else could happen instead? What else? Okay, but what else?” Keep pushing until you break through the limits of how you think your story is “supposed” to go. Take it somewhere new, terrifying, and utterly marvelous.

*The term “romance” was a generic category at that time for all types of fiction that dealt largely with the characters’ interactions with the outside world (such as what we now call adventure, science fiction, fantasy, or horror), rather than their inner intellectual or emotional lives. Laura’s academic journal article that expands on these themes can be downloaded from her web site.

Laura E. Goodin is an internationally published novelist, playwright, and poet. Her debut novel, After the Bloodwood Staff, came out in December from Odyssey Books, and her next novel, Mud and Glass–which started out as a NaNo novel–will be released in April, also from Odyssey. She lives in Melbourne, Australia, and teaches writing at Deakin University. She spends what little spare time she has fencing, riding, camping, and otherwise trying to be as much like Xena, Warrior Princess, as possible. Visit her website, blog or Facebook for more.

Top photo by Flickr user Chris Malec.

March 8, 2017

5 Famous Female Authors Who Wrote Under Male or Androgynous Pen Names

Throughout history, authors in all genres have used pseudonyms for a variety of reasons, sometimes writing under as many as three, or four–or more!–pen names. Today, in honor of International Women’s Day, we’ve compiled a list of some of the most influential women writers who have had to write under male or androgynous monikers at some point in their careers:

1. Zeb-un-Nissa

1. Zeb-un-Nissa(1630-1702)

Zeb-un-Nissa was an Imperial Princess of the Mughal Empire in India. She was a dedicated scholar, and fluent in three languages (Persian, Arabic, and Urdu). She is said to have loved reading so much that her personal library became the best in the Empire.

Zeb-un-Nissa was also an accomplished poet, and started writing and reciting her own poetry as early as 14 years old. Although her father, Emperor Aurangzeb, disapproved of her writing, she continued to do so under the male name “Makhfi”, which generally translates to “The Hidden One”.

Later in her life, Zeb-un-Nissa was arrested and imprisoned. Accounts vary on the reason for her imprisonment, but one theory is that her poetry threatened the austere, orthodox rule of her father. Although she died after many years in prison, her poems continue to be popular.

Via an excerpt from the Library of Congress website.

2. The Brontë Sisters

2. The Brontë Sisters(1816–1855)

Ok, so this means our list technically contains more than five authors. But we found it impossible to pick a favorite from the three sisters.

Although the names of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë are now well-known to everyone from high school students to classic novel enthusiasts, this was not always the case. When they began publishing their novels, the Brontë sisters used the male pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, respectively.

Charlotte summed up their reasoning for using the aliases best: “We did not like to declare ourselves women, because–without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’–we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.”

Via Heather Armitage in this article for Culture Up.

3. Pearl S. Buck

3. Pearl S. Buck(1892–1973)

Despite critical acclaim–including receiving a Pulitzer Prize for her novel The Good Earth and a Nobel Prize for Literature–Pearl S. Buck sometimes wrote under the masculine pseudonym “John Sedges” in the later stages of her career.

In her own words, Buck said that she chose a masculine pen name “because men have fewer handicaps in our society than women have in writing as well as in other professions.” She also felt that female authors “are not taken as seriously as men, however serious their work. It is true that they often achieve high popular success. But this counts against them as artists.”

Via Vanessa Künnemann in Middlebrow Mission: Pearl S. Buck’s American China.

4. Alice C. Browning

4. Alice C. Browning(1907–1985)

Alice C. Browning was an American teacher, writer, editor, and publisher. She lived and worked in Chicago, where she created platforms to highlight African-American voices in literature. From 1944 to 1946, Browning published a literary magazine, Negro Story, and later founded and directed the International Black Writers Conference.

In the words of Professor Bill V. Mullen in Writers of the Black Chicago Renaissance:

“Browning’s stories appeared regularly in Negro Story. Nearly always she wrote under the pseudonym ‘Richard Bentley.’ This possibly reflected her desire to mask her role as editor and writer for the magazine. It also was a symbolic reminder, for readers and friends who knew her, of the impetus for starting the journal: namely the feeling that Black women and women writers in particular were being shunned by mainstream literary markets. The pseudonym also gave Browning perhaps playful free rein to write and publish stories that foregrounded taboo gendered and racial themes.”

5. Joanne Rowling

5. Joanne Rowling(1965–Present)

It’s hard for us to imagine an alternate universe where Harry Potter isn’t one of the bestselling book series of all time. But before Harry ever took his first trip to Hogwarts, publishers weren’t so sure that the book would be a blockbuster hit.

Before the release of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, publishers were concerned that young male readers would refuse to pick up a book penned by a female author. They convinced author Joanne Rowling to go by the non-gender-specific initials “J. K.” to draw in that demographic of readers. (Fun fact: Ms. Rowling does not, in fact, have a middle name. She chose the “K” in honor of her grandmother, whose name was Kathleen.) In an interview, Rowling commented: “It was the publisher’s idea; they could have called me Enid Snodgrass. I just wanted it [the book] published."

Via Richard Savill in this article for The Telegraph.

While it may seem hard to imagine that publishers could still carry a (conscious or unconscious) bias against women–especially after success stories like Rowling’s–some recent social experiments have shown that this is still an issue. In honor of National Women’s History Month, let’s celebrate and recognize all the amazing women who write.

Chris Baty's Blog

- Chris Baty's profile

- 63 followers