Michael S. Fedison's Blog, page 16

December 6, 2014

To Entertain or to Illuminate, That Is (Not) the Question . . .

On September 22, 1959, on the eve of the premiere of the new television series The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling sat down for an interview with Mike Wallace.�� Serling, by that time already considered one of television’s brightest writing stars, had amassed a formidable resume.�� He was known throughout the industry as television’s “angry young man” due to his ardent and very vocal criticism of the censorship so rampant in the medium at that time.

Determined to produce gritty, realistic scripts that dealt with injustice, inequality, and greed, Serling wrote for Kraft Television Theater, Playhouse 90, and other venues that featured live TV dramas of the day.�� His breakthrough script, “Patterns,” which aired in February 1955, launched him into orbit, and by the time of the Wallace interview, Serling, already a winner of three Emmy awards, was an established industry heavyweight.

At the start of the interview, Wallace credits Serling as the accomplished writer he is; he discusses Serling’s rise within the industry, and his ongoing battles against sponsor-mandated censorship.�� About midway through the conversation, the discussion takes a turn . . .

“You’ve got a new series coming up called The Twilight Zone,” Wallace says, and simply from his tone of voice, his delivery, one can sense Wallace’s disappointment.�� After all, in the interview, Serling himself admits to be being “tired,” and that he doesn’t “want to fight anymore”–with corporate sponsors and their dictates on what can and cannot be included in his scripts.�� The Twilight Zone, a short, half-hour sci-fi and fantasy excursion, was deemed by many, Wallace among them, as a sellout on the part of one of TV’s most serious and hard-hitting writers.

Wallace suggests the episodes will be “potboilers,” which Serling rejects, stating that he believes the shows will be “high-quality . . . extremely polished films.”

Undeterred, Wallace then says, “For the time being and for the foreseeable future [since Serling would be so focused on The Twilight Zone going forward], you’ve given up on writing anything important for television, right?”

Even here, Wallace is not finished. He quotes TV producer Herbert Brodkin as saying, “Rod is either going to stay commercial or become a discerning artist, but not both.”

To which Serling replies, “I presume Herb means that inherently you cannot be commercial and artistic.�� You cannot be commercial and quality.�� You cannot be commercial concurrent with having a preoccupation with the level of storytelling that you want to achieve.�� And this I have to reject. . . . I don’t think calling something commercial tags it with a kind of an odious suggestion that it stinks, that it’s something raunchy to be ashamed of. . . . I think innate in what Herb says is the suggestion made by many people that you can’t have public acceptance and still be artistic.�� And, as I said, I have to reject that.”

***************

When I was an English major in college, there was a fellow student, named John, who shared several classes with me.�� I’ve blogged about John before.�� In addition to wanting to create something new, uniquely his own, John also wanted to create something artistic, arcane, even inaccessible.

“If just anyone can understand it,” he said once, “then I’ve failed.�� I’m not writing for the layperson.�� I’m writing for the select few.�� If John Q. Public ‘gets’ my story, then what’s the point?�� Anyone can write a story like that!”

I understood his sentiment–up to a point.�� All writers, all artists want to say something, to have one of their stories or songs or paintings or performances move an audience to tears, open eyes, create dialogue, and promote new viewpoints.�� We all want our work to matter.

But I strongly disagreed with his assertion that a work is somehow elevated if it’s nearly incomprehensible; that a story can only have merit if it needs a literature professor to explain its themes, ideas, and structure to a room full of confused and bored students.

Sure, I want my stories to make people to stop, think, perhaps question things they hadn’t even considered before, or, if they had, maybe the story enables them to see something familiar through a different lens, changing their perspective, granting them a peek on the other side of the mountain, as it were.�� But to accomplish that, I don’t believe I, or any other writer, needs to create a piece that requires a literary road map through which to navigate.

Certainly it is my hope that The Eye-Dancers will prompt readers to step back and think about the very nature of what we term “reality”; to consider the mysterious, even seemingly otherworldly psychic connection two strangers can share; and to wonder at the possibility that we, each of us, are just one piece of an infinite puzzle that includes countless variants of ourselves scattered throughout worlds that parallel our own like invisible, silent shadows.

But more than this, it is my hope that readers will relate to the characters, cheer them on, root for them, get swept up in the flow and momentum of the story, and have fun as they read.

When I explained this to John, when I told him I wanted a wide swath of people to enjoy my stories, not just a select few, he simply shook his head and gave me a look that I could only interpret as pure pity.

************

The Twilight Zone remained on the air for five unforgettable seasons; and those “potboiler” episodes, those flights of fancy that delved into the genres of science fiction and fantasy, those “commercial” attempts at expression have endured and prospered.�� It can be argued, indeed, that The Twilight Zone is more appreciated, more loved, more respected now, on the precipice of 2015, than it was when it actually ran.

Serling himself expressed a possible reason for the show’s ongoing popularity.�� “On The Twilight Zone,” he once said, “I knew that I could get away with Martians saying things that Republicans and Democrats couldn’t.”�� He was able, in other words, to utilize imaginative storytelling, plots that took viewers by the hand and led them to strange, often frightening new worlds, to comment on and critique the social ills, prejudices, and personal crises occurring in our own, very real lives.

The Twilight Zone accomplished Serling’s vision and proved beyond a doubt that a story, a novel, a piece of art, does not need to choose between entertaining and illuminating its audience.

The great pieces, the truly memorable works that hold up through the dust and years and passing of decades and centuries are the ones that accomplish both.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

November 21, 2014

A Season of Thanksgiving, a Milestone Reached

I am always amazed at how time flies–or so it seems. “The more I see, the less I know for sure,” John Lennon once said. But it certainly feels like time speeds along, as if it were some majestic, brightly colored bird, wings outstretched, slicing through the crisp, still November air.

It is hard for me now, sitting in front of my trusty old PC, to believe that I began writing The Eye-Dancers back in the first decade of this century, or that I started to conceive of an Eye-Dancers blog more than thirty full moons ago. Perhaps, as Einstein said, time is an illusion. How else to explain the swift passage of months and years?

When I began this blog, I hadn’t a clue what I was doing. (It can be argued that I still don’t!) I had just written a novel, and planned on publishing it. Other than myself, a few friends, and immediate family members, not a soul anywhere on earth or beyond knew of the soon-to-be book. I needed a vehicle, something, anything, to “get the word out.” One of the things I decided upon was a blog devoted to the novel, its characters, its themes, its inspirations, and the process that went in to writing it in the first place.

It was a daunting task. I knew nothing, less than nothing, about blogging, and had no idea if anyone “out there” would want to learn more about the novel, read about my interests, my take on writing and creativity, read my short stories . . . It almost seemed egotistical. Who was I to begin a blog? Who was I to try and promote a book? The doubts were very real. As were the worries. When I posted my first blog entry, I wondered, first and foremost, if it would be the online equivalent to a black hole and if anyone would even see it or read it; and, second, what their response might be if they did . . .

But I also knew I had spent over two years writing and editing The Eye-Dancers. I felt strongly about it, and I did not want the book to lie in a dark dresser drawer, or on a computer hard drive, as the case may be, collecting (virtual) dust, hidden from the world.

“If you have built castles in the air,” Thoreau said decades and decades ago, from the mists and echoes of the nineteenth century, “your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.” That was what I intended to do. I had a hammer, a chisel, and a determination to keep at it.

Now I just needed to see how my posts would be received.

I learned very early on that there was no cause for concern. No one came on the site and blasted the concept. No one said, “Go home, you talentless wannabe. We don’t need another sci-fi/fantasy blog!” On the contrary . . . right from the first, fellow bloggers were welcoming, kind, interested, and, above all, supportive. For a new blogger like me, it was just the encouragement I needed.

Gradually, slowly, day by day, The Eye-Dancers blog grew. I remember the snowy winter day, nearly two years ago now, when I reached one hundred followers. One hundred! It was more than I had hoped for when I’d started. It served as a tonic, a motivation to keep at it and keep going.

Fast-forward to early November 2014, when The Eye-Dancers reached a milestone, going over 3,000 followers. I never would have imagined this website would stick around this long, or continue growing as it has–and it wouldn’t have, it if it hadn’t been for the WordPress community. I can’t thank each and every one of you enough.

Because of you–your comments, support, interest, and willingness to read these random scribblings I come up with, The Eye-Dancers site has evolved from a place where I originally intended to simply promote my novel to a community of dreamers and writers and artists and thinkers and poets and friends. It is a joy for me to be a part of.

So consider this post a thank-you, from me to you in this month of Thanksgiving. And though I’ve been blogging for over two years now, I can honestly say–this is still only just the beginning.

There are so many posts yet to write, so many blogs to enjoy, so many dreams to dream.

Perhaps that last part is the most important–for all of us. The Eye-Dancers, both the novel and the blog–is all about looking up at the stars on a clear night, seeing them sparkle, like distant diamonds in the sky, and having the courage and hope and faith to believe . . .

“Far away there in the sunshine are my highest aspirations,” Louisa May Alcott once wrote. “I may not reach them, but I can look up and see their beauty, believe in them, and try to follow where they lead.”

Thanks so much to all of you in the WordPress community for helping me, and inspiring me, to keep on reaching. You’re the best.

And thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

November 6, 2014

Short Story — “The Beggar”

The Eye-Dancers, it’s my hope, tackles, among other things, the very concept of what we term “reality.” What does “real” mean? And is the line that separates “reality” from our perceptions and dreams and nightmares truly as distinct as we might imagine? What other worlds and universes exist, and how can two strangers, so far apart it’s nearly impossible to imagine the distance, share a psychic connection, a cosmic bond, with one another?

Of course, there are many ways a story can question our perceptions and our views of reality. Over ten years ago, I wrote a short story titled “The Beggar,” in which the protagonist is confronted by something, and someone, who ultimately contradicts some of his long-held assumptions and challenges the way he looks at the world.

I hope you enjoy “The Beggar.”

“The Beggar”

Copyright 2014 Michael S. Fedison

*****************

Looking through the bus window, Mark saw the beggar. The old man was standing in front of a middle-aged blonde woman, no doubt asking, pleading, for money, just a dollar, just a quarter, anything to help out. Mark knew the routine. He’d been on the receiving end of it more than once.

“Look at that old loser,” Mark’s seatmate, a prematurely graying accountant named Harold Gardener, said. The bus slowly lumbered on, and the beggar disappeared, as if by magic. A Winchell’s Donuts, a Burger King, and the entire assortment of suburban paraphernalia came into view and then slipped past in a never-ending display of sprawl. “I’ve seen that freeloader way too many times. Why don’t they arrest him? Or shoot ‘im.”

Mark said nothing. He sat with Gardener several times a week—the accountant worked four blocks north of Mark’s office and never said good-bye when Mark got up to leave, so Mark had stopped saying good-bye, too—but he’d learned early on that they disagreed on most issues, the beggar among them. Gardener seemed to hate him, eyeing him as he would the carrier of some soul-infesting disease. But Mark could sympathize with the old man. Even the word beggar sounded distasteful to him. Maybe the guy was all right. Maybe he’d even been successful once.

“Filth, that’s what bums like that are,” Gardener continued. He glanced at Mark, as though awaiting a reaction. When he didn’t get one, he said, “I didn’t move my family out here to deal with filth like that. Know what I mean?” With that, Gardener faced forward, looking at the brown hair of a businesswoman seated in front of him.

Mark looked at Gardener. “I think you’re too hard on him. I mean, c’mon, filth?”

Gardener snorted. It was the kind of sound a man makes when in the presence of unspeakable stupidity. “I see enough of those bums in the city. Down by Coors and the train station. I don’t need to see them here.”

Mark thought of pursuing the conversation, but he didn’t. He knew Gardener’s view of the old man was set in granite, and it was just too early for an argument. Better to let it rest. Hopefully, they wouldn’t see the beggar again. The bus rarely passed him.

But Mark had seen the old man several times, never knowing when or where he’d turn up. The beggar seemed as unpredictable as the weather. The first time Mark encountered him, in fact, he had been walking down the litter-free streets of an upscale neighborhood.

♣

It had been a chilly day in mid-October, with a perfect Colorado blue sky and a tang in the air that felt so pure and fresh, Mark wanted to take a bite out of it. He was enjoying his daily lunch stroll, walking through the neighborhood behind his office. He rarely failed to take a walk at lunchtime, even during winter cold spells or spring snowstorms or summer rain showers. It was a running joke at the office. They said, rain or sleet or snow, Mark will take his walk, even more reliable than the postal service! You could set your clock to it. But he didn’t mind the teasing. At least he stood out for something. Besides, it was good to get away from the cubicles and the people and the stress. It was—

A gaunt old man with a full, gray beard and a tattered wool hat turned the corner at the nearest stop sign. He was heading toward Mark.

Mark did a double-take. The man’s appearance did not fit in with the affluent surroundings of the neighborhood. Most of the lawns were large and well-tended, and the houses—sleek, new ranches with attached garages and gigantic western-facing windows—all looked shiny and polished, as if they had just been given a coat of varnish.

Not wishing to judge a book by its cover but unable to avoid it, Mark quickly deduced the man was a vagrant. Trying to appear indifferent, acting as if it were the most natural thing in the world, Mark slowly crossed the street, wanting to avoid the man without making it look so obvious. He whistled a tune as he did, giving the performance an air of nonchalance it otherwise might have lacked. He focused his attention to the west. Over the rooftops of the ranches, the distant snowcapped peaks of the Front Range sparkled like sunlit diamonds.

“Pardon me, young man? Young man?”

Mark turned his head. The drifter was there, staring at him. He berated himself. While he had been carelessly enjoying the view, the old-timer must have snuck up on him.

“Do you live here?” The beggar had no teeth that Mark could see. His face was covered in a scraggly forest of white hair. His wool hat had holes in it. It looked nearly as old as the man who wore it.

“Uh, no, no, I just work here.” Mark was looking for an out. He could have simply walked away—he knew most guys would—but he couldn’t bring himself to do it. His wife had always told him how much she appreciated his sensitivity. Right now, he wished he could be as bottom-line oriented and callous as Gardener. “I work over on East Hampden. I’m just taking a walk.”

The old man nodded, then said, “It’s good that you have a job. I had a job once. A whole bunch of them. But I don’t have one now. What do you say, my young friend? Can you help a fella out? I didn’t eat any breakfast this morning, and my stomach’s groaning.”

Mark couldn’t believe how fast the man had launched into his sales pitch. He started to walk away.

“Hey, wait!” the old man said, following Mark. “Even a dollar would help! Even a quarter.”

Mark kept walking, but the man had caught up with him. “Why are you in this neighborhood, mister?” Mark asked. He picked up his pace. So did the beggar. “You might get arrested just for hanging around here. You shouldn’t be here.”

“Oh, I know,” the man said. He was huffing now, struggling to keep up with Mark. “People here are much too good to even look at me. But I wanted to do something different today. Is that so bad?”

“No, it’s just—”

“And then you came along, and I thought—‘well, what a break. That nice young fella will help me buy some lunch. Thank the Lord for his kindness’. That’s what I thought, yessir. Now, how about it, fella? Give an old man a break, huh? Just a few bucks. A few measly bucks. What’s it to you?”

They walked past a white ranch with skylights and a privacy fence to the rear and sides. A young woman in a ponytail was working in her flower garden, preparing it for winter. She eyed Mark and the beggar with suspicion. What is that grungy old man doing on my street? her look said. We don’t have people like that on my street. Mark shot her a disapproving look right back, and suddenly felt a strong impulse to give the man some money.

Turning a corner, walking past more polished, white ranches, Mark stopped. The beggar stopped, too, then bent over and gasped as if he had just sprinted five miles and needed to get his wind back.

“You walk too fast, young man,” the drifter said once he had sufficiently recovered. “Give an old guy a break.”

Mark took out his wallet, fished inside, then handed the man a ten dollar bill—and imagined how fiercely his wife would protest. He had been stopped by beggars before, and he almost always gave them something. One time, two summers ago, she let him have it after he had given some guy a twenty.

“What’s the point?” she had said. “All they do is go spend it on booze. They’re better off without it.”

“But he said he wanted to buy something for his daughter. He said—”

His wife rolled her eyes. “Oh, please, Mark. Spare me.”

“I thought you liked my sensitivity,” he said, a pout on his face. He fought to remove it. Pouting never worked with his wife.

“There’s a fine line sometimes,” she said, frowning, “between sensitivity and stupidity. Giving a beggar a twenty and thinking he’s gonna spend it on something other than booze? That, I’m afraid, crosses the line.”

That ended the discussion. He thought about pressing his case—the man’s eyes had looked so honest, so needy—but he admitted to himself that his wife was probably right. Still, what could he do about it? She’d told him before he had a face that attracted beggars.

“What?” he’d protested. “How so?”

“Because,” she’d replied. “They can see you’re a softie.”

Last year, they’d moved out of Denver and headed southeast. They now lived in a brick ranch several miles outside the city. Their neighborhood was quiet, even dull, but peaceful. And there were no beggars. He worked in Aurora, and for a while he hadn’t had to deal with any beggars there, either. But the old man in the wool cap changed all of that.

Handing the ten dollar bill to the man, Mark resolved not to tell his wife about it.

“Bless you, son, bless you!” the man gushed. He seemed like a kid on a treasure hunt who has just discovered the coveted prize. It made Mark uncomfortable. The man’s ridiculous display, his outright begging—he had no pride, no dignity. That’s what bothered Mark the most, and that’s what made him think he could never beg for money himself. “You don’t know how grateful I am!” the old man said.

“It’s okay, really,” Mark said. “Just go get something good to eat. No big deal.” He looked around at the white ranches. No one was outside. But that didn’t mean someone wasn’t watching this spectacle from behind a window. He told the old man he needed to get back to the office.

“Bless you, young man,” the beggar repeated when Mark started to walk away. “I’ll never forget this.”

I hope you do, was all Mark thought.

♣

The bus did not pass by the beggar again for a long while. And Mark himself had been spared dealing with the old man, too. After that first encounter, he’d been flagged down by the beggar a handful of other times—and he always gave the man a dollar or two, never again a full ten—but it now had been months since their paths had crossed. That was okay with Mark. He suspected his wife’s harsh view applied to this beggar as much as it did to any other—though he never recalled having smelled alcohol on the man’s breath.

As more time passed and he didn’t see the beggar, Mark wondered if maybe the old man had moved on to another section of town, or even died. It certainly was possible. He had to have been at least seventy, and, with his vagabond lifestyle, he couldn’t have been in good health. The possibility of the man’s death had no effect on Mark. It did not sadden him. What was an old drifter to him? Nor did it please him. He was positive the beggar’s death would please Gardener, though.

But the old man was not dead.

♣

“I swear, if he ever tries that with me again, I’ll punch ‘im, tear ‘im in half!” Gardener raged. “Old freeloading . . . ”

“Where’d you see him?” Mark asked.

“Right outside my office! Can you believe it? The nerve of those people!” The bus worked its way through streets still soaked from on overnight thundershower. But the sky was brightening by the minute, and warm spring sunshine filtered through the window, striking Gardener on the side of his face.

“I thought he might be dead. I hadn’t seen him in a while,” Mark said.

“Well, he’ll wish he was dead if he ever asks me for money again! Old piece of—”

Mark tapped Gardener on the elbow and nodded imperceptibly (he hoped) across the aisle. Gardener glanced in that direction, at the people seated across from him and Mark. An old woman with a floral dress sat next to a little girl with pigtailed blonde hair. The woman was glaring at Gardener—and Mark—and the girl was gaping at them with wide-eyed delight, as though she were hoping to hear a forbidden word. Mark had never seen either of them before, and he doubted he’d see them again.

Gardener clenched his teeth and whispered, “Great. Now I can’t even talk about it.”

“That’s why a wife is good,” Mark offered. “Great sounding board.”

Gardener shook his head. He’d said before he wasn’t the marrying kind.

“What did you say to him?” Mark asked. He didn’t understand why he cared, but for some reason, he did.

“I told ‘im—” Gardener said, his voice loud again, and Mark nudged him. Stealing a quick glance across the aisle, Mark was sure that if the old woman’s eyes could shoot laser beams, both he and Gardener would be vaporized by now. The pigtailed girl was still smiling. From the back of the bus, there was laughter. From the front, a few muffled words, but mainly silence, save for the drone of the bus’s engine and the swoosh of the tires as they sloshed through the rain-drenched street.

“I told ‘im to get his filthy, lice-infested self out of there,” Gardener said quietly, obviously fighting to keep his temper in check. “I told ‘im to go beg somewhere else, or go stand in front of the next garbage truck he sees. Then they could run ‘im over, pick ‘im up, and take ‘im to the dump with the rest of the trash.”

Mark said, “Man, you really hate that guy, don’t you?”

“Yup,” Gardener said. “Like I hate fleas, or roaches. Pests. Like I hate pests.”

♣

That day on his lunchtime walk, Mark crossed paths with the beggar. It had been so long since he’d seen him, it caught him by surprise. He was walking through a different neighborhood today, several blocks away from the office. The houses in here were not as polished, not as large, and several For Sale signs dotted the bottoms of lawns. He liked this neighborhood, in part because it did not feel so suffocating, in part because it had a lot of trees—primarily maple, Russian Olive, and spruce, but there were also a few aspen and dogwood. He also liked it that no one else from his office ever walked through this area. Some of the others strolled through the upper-class neighborhood close by, but no one came this far out. Any time he really needed to get away from it all, he came here.

He had been thinking of what to get his wife on their wedding anniversary in August. It would mark their eighth year together, which amazed him. It seemed just yesterday that they had exchanged their vows. He wanted to surprise her this time, really come up with something original. But before he could construct a mental list of potential possibilities, he spotted the beggar.

He had just turned a corner and was walking toward Mark, briskly, with a purpose, as if he’d known Mark would be walking down these streets today. Mark brushed that idea aside as sheer foolishness. Just a coincidence, that’s all, and not a very appealing one. He didn’t want to deal with the old-timer today. He hated the begging, the loss of all self-respect. If the drifter was not embarrassed at his own behavior, Mark was embarrassed for him. Instinctively, he felt for the bulge in his pants pocket—his wallet. He was pretty sure he had a few singles in there.

This time, Mark did not pretend he wanted to cross the street. He walked straight for the old man. The best thing to do, he figured, was to get this over with, give the man some small bills, then cut short the “bless you, young man” performance that would undoubtedly follow.

They approached each other. Mark looked down at the pavement. If the beggar wanted to stop him, he would. If not, Mark would keep right on walking. No reason to offer money unasked.

“Young man, young man.”

Why am I not surprised? Mark thought. He noticed the beggar was still wearing his wool hat, despite the heat of the day.

“Hey, slow down, and give an old guy a break, huh?” the man said. “Don’t make me run after you again.”

Mark came to a stop. He and the beggar stood on a sidewalk in front of a beige ranch with a roof that looked like it needed repairing. Mark thought that roof must have leaked last night, during the rain storm. A tall maple tree, its leaves still wet and glistening in the sun, provided the two of them with welcome shade.

“You remember me,” Mark said.

“Of course I remember you. Ten dollars last fall. Made me have a heart attack almost, chasing after you that way. And whenever I’ve seen you since, you’ve been generous.”

Mark winced. Generous? What was a dollar or two? He wondered if most people responded to the old man the way Gardener did. If so, it was easy to see how his pittance had seemed generous to the man. He reached into his pocket, pulled out his wallet, and took out a five dollar bill.

“Here you go, mister.”

The beggar just looked at the bill, then at Mark. Tears welled up in his eyes and spilled out into the tangled, gnarled beard that covered his cheeks. Then he shook his head. “No,” he said. “Not today.” He reached into his own pants pocket, and for a moment, Mark worried that the old man was going to pull out a gun. But all he had was a one dollar bill. “I know it isn’t much,” he said. “But take it, and please know I’d give more if I could.”

Mark stood there, and he felt his jaw drop open. He didn’t know if he should feel honored or insulted. What exactly was going on here? In the distance, from somebody’s backyard, he could hear the giggling of a little girl.

“Look,” Mark said, “just take this, okay?” He thrust the five dollar bill out further. “Go buy lunch with it.”

The beggar shook his head fiercely. “No! Take my dollar! I’m giving it to you. Don’t you see? I’m giving it to you! I don’t want your money today. Please take it.” The man’s hand was trembling, and the dollar fell to the ground. Mark snatched it up. “Keep it,” the old man said, then started to walk away.

Mark easily caught up with him. “Wait!” he said. “I don’t need your money, mister. Take it back, and take the five, too.”

The beggar brushed past Mark. He continued walking. Shaking his head even harder, he said, “You don’t understand, you don’t understand.” Then he reached the next intersection and turned the corner.

Mark just stood there on the sidewalk, feeling stupid and sad. He folded his five and the beggar’s one and stuffed them into his wallet.

“Thanks for the dollar, old man,” he said.

In the distance, he heard the little girl giggle again.

♣

Gardener wasn’t on the bus today. He was probably in bed with the flu. A nasty bug was going around. It was September, and a cold snap had come in strong and bitter, blowing down from the mountains and reminding everyone that winter was not far off. Mark heard that the people of Vail had awakened to nine inches of snow that morning. But that just made him smile, as he thought of the anniversary gift he had bought for his wife last month—a weekend stay at her favorite ski lodge the second weekend of December. He had everything reserved, right down to the privacy booth in the restaurant she liked. All he needed now was for the mountain weather to cooperate. With nine inches of snow already, things were headed in the right direction.

Mark sat by the window. People on the sidewalk were bundled in winter coats and scarves. They were shivering, not used to the below-freezing temperatures. Just last week, it had been in the eighties.

“Whew, it’s freezing out there,” Mark heard someone say. A young woman with flushed cheeks sat down beside him. “Feels like February.” She took off her hat and scarf and placed them in her lap. Long black hair fell over the puffed bulk of her winter coat. She looked familiar to Mark, but he had never sat next to her before.

“Yeah,” he said. “Good weather for sleeping in, huh?”

“Tell me about it,” she said. “I wish I could. But, duty calls, y’know?”

He just smiled. The bus slowly worked through its rounds. Three stops before he would get off, Mark spotted the beggar. He had his coat wrapped tightly around himself, and he was talking to a young blond-haired man on the sidewalk. Mark saw the blond man hand the beggar a bill. He couldn’t tell what denomination, but he saw the old drifter smile and nod, almost bow, and he could read the lips: “Bless you, son, bless you.”

The bus pulled away from the curb.

“I don’t think I could ever do that, could you?” the woman next to Mark said.

“Do what?”

“Give away money like that guy just did. I mean, I feel bad for someone who doesn’t have a bed to sleep in at night and all, but, I mean, like, what do they do with five bucks? It isn’t gonna really help them get a life or anything.”

“No,” Mark agreed, “but maybe it can buy them a hot meal.”

The woman shrugged. “That’s what the shelters and soup kitchens are for. They can get their meals for free there. It just bothers me, the way they come up to you and just, like, beg. They have no respect, for themselves or anybody else. Being that poor, I guess it makes you self-centered, y’know? Never thinking of anything but your own needs. Always wanting to take.” She shook her head. “I wouldn’t give him a penny.”

At the next stop, she got up.

“Keep warm,” she said, then headed for the door.

Mark nodded and smiled. But he didn’t feel warm at all.

*****************

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

October 25, 2014

Hail and (Never) Farewell

Have you ever wondered, “What if?” What if you could fly–not with the aid of an eighty-ton aerodynamic metal ship, but simply with the rising and falling of your arms? What if you could travel to Mars, or Jupiter, or Venus, and, once there, discover that other forms of life, non-earthly forms of life, exist elsewhere in our solar system? What if you could go backward in time, millions and millions of years, to a green, jungled past inhabited by monstrous flying reptiles and larger-than-life thunder lizards that we of today can scarcely imagine?

Have you ever asked?

Of course you have. We all have. “What if?” it can be argued, is the great creative expression, the launch pad to unforgettable stories and adventures.

One of my favorite authors, Ray Bradbury, frequently asked, “What if?” And, in fact, he asked the very questions presented above.

The stories that resulted, masterpieces such as “Here There Be Tygers,” “The Long Rain,” and “A Sound of Thunder,” among many others, are gems of the highest order.

But there was another “What if?” question the prolific author asked . . . What if you never had to grow old? What if you could stay forever twelve, forever young, regardless of the date printed on your birth certificate?

The resulting story, “Hail and Farewell,” is not as well known perhaps as some of Bradbury’s more recognizable tales. But that takes nothing away from the story’s impact, power, and poignancy.

“Hail and Farewell” is about a twelve-year-old boy named Willie. When we first meet Willie, and indeed, when anybody first meets Willie, he seems like any other twelve-year-old. He looks twelve; he’s not inordinately big for his age–in fact, he is quite small. If you were to walk by Willie on a street corner, you probably wouldn’t look twice–just an ordinary boy, perhaps returning home from school or strolling to a Saturday matinee or walking over to a friend’s.

But Willie is not your average, normal twelve-year-old boy–not by a long shot. Willie is not, in actuality, twelve at all. He is forty-three. That’s what his records show, those are the facts. But Willie discovered, long ago, that, in terms of outward appearance, he is forever twelve. He cannot grow old. He’ll never wrinkle, lose his hair, acquire the maladies and infirmities of old age. A blessing of the highest order? Perhaps. But Willie also has a price to pay . . . a repeating cycle with no end.

He can never settle in, never remain. He is a drifter, moving from town to town, school to school, state to state. He learns of couples with no children, patiently, thoroughly researching his opportunities, trying to discover the people in whose lives he can inject some love and laughter, if only for a little while. And then–Willie just appears. He knocks on a door, rings a bell, and when the door opens, he introduces himself, and, if the stars are aligned, he will have found a new home, a new temporary set of parents. He will stay with them, love them, bond with them. But then he will need to leave. After all, how can a boy remain twelve forever? Classmates will mature, graduate, go on to college and careers. Parents will gray and grow old, all while Willie stays a boy, always on the threshold of adolescence, but never quite reaching it. So he can stay for two years, maybe three, and then he is gone . . .

Bradbury’s story essentially asks the question, “Would it be a blessing to remain forever young? Or a curse? Or maybe a little of both?”

Those are questions each reader must answer for him- or herself.

But there is another way each of us can remain forever twelve. In our own way, we all have a little bit of Willie in us . . .

**************

In The Eye-Dancers, main characters Mitchell Brant, Joe Marma, Ryan Swinton, and Marc Kuslanski are all twelve years old. They are all also inspired by friends I knew growing up; and so, as I wrote the novel, I was, in many ways, twelve years old again. I spent the better part of three years continually entering the minds and consciousness of my pre-teen characters, seeing the world through their eyes, hearing it, feeling it, experiencing it as a twelve-year-old might. (Some might argue I operate that way anyway, all the time, as my default mode! But that is a post for another day.)

It is also my hope that readers of The Eye-Dancers are able to share in that experience, too, hopping on, as it were, a literary time machine traveling back, back . . . to younger days–days that seem, sometimes, almost forgotten, like yellowed pages in a time-worn scroll. But then, when you rediscover them, when the aroma and memories and sights and sounds and experiences flood back in, you realize–they were there the whole while, stacked in a neat pile just outside the door.

The door just needed to be opened.

**************

“But of course he was going away,” Bradbury writes in “Hail and Farewell,” as Willie must leave another couple, and begin anew. . . . “His suitcase was packed, his shoes were shined, his hair was brushed, he had expressly washed behind his ears, and it remained only for him to go down the stairs, out the front door, and up the street to the small-town station where the train would make a stop for him alone. Then Fox Hill, Illinois, would be left far off in his past. And he would go on, perhaps to Iowa, perhaps to Kansas, perhaps even to California; a small boy twelve years old with a birth certificate in his valise to show he had been born forty-three years ago. . . .

“In his bureau mirror he saw a face made of June dandelions and July apples and warm summer-morning milk. There, as always, was his look of the angel and the innocent, which might never, in the years of his life, change.”

We are all like Willie, I think, each in our own way. But where Willie lives in a perpetual state of comings and goings, hellos and good-byes, bonding and heartbreak, we need not have to experience his gift in such a transitory manner.

As writers, readers, dreamers, we can all say “Hail,” without the need of ever having to say, “Farewell.”

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

October 11, 2014

“Nick of Time”–Or, a Three-Month Holiday Promotion!

In a second-season Twilight Zone episode titled “Nick of Time,” newlyweds Don and Pat Carter, on a honeymoon trip cross country to New York City, are temporarily stranded in the small town of Ridgeview, Ohio, while their car is repaired. With several hours to kill, they enter a nondescript diner.

As they sit down at a booth, they notice a “mystic seer”–a penny fortune-telling machine. “Ask me a Yes/No question,” the machine reads. “One cent per question.”

Don, up for a promotion at his place of employment and obsessing over the outcome, honeymoon or no, inserts a penny and asks the machine about it. Has he been promoted at work? He presses down on the lever, causing the machine to jingle, and a slip of paper spits out.

“It has been decided in your favor,” the slip reads.

Don decides to make a long-distance call back home, to the office, to find out if this is really true. It is. He’s made it.

“And he knew,” Don says, sitting back down at the booth, pointing at the mystic seer.

Amused, he decides to ask the fortune-teller another question. Would they really have to wait four hours for their car to be fixed?

“You may never know,” the machine responds.

Taken aback, Don asks more questions. The answers are cryptic, threatening even, but they always fit, always make sense. He grows more frantic, while his wife becomes concerned. Why is he taking this thing so seriously?

The seer suggests they should remain in the diner until three o’clock. Looking at his watch, Don sees it’s only quarter after two.

“If we don’t stay here till three, something bad will happen to us?” he asks the seer.

The machine answers, “Do you dare to find out?”

With each answer, Don’s wife grows more upset. “Let’s go,” she says. But Don stalls, says he hasn’t finished eating, hasn’t ordered ice cream yet. Finally, at five minutes before three, Pat coaxes him to leave the diner.

As they walk outside and cross the street, a car nearly runs into them. They escape unscathed, but it was a close call. Don looks at the church tower clock across the street as soon as they reach safety. Exactly three o’clock–just as the seer warned.

He convinces his wife to go back inside the diner. Why is the machine so accurate? He is determined to find out.

“You don’t really think that gizmo can foretell the future, do you?” Pat asks him once they’re back inside.

“Well, it foretold ours,” he says.

She refutes this, saying it was Don himself who provided the machine with the details. All the seer did was churn out vague generalities.

Don asks the machine if it knows about the car that almost hit them.

“What do you think?” the ejected card reads, in response.

He then asks if it will still take four hours for their car to be fixed.

“It has already been taken care of,” the seer responds. Not a minute later the mechanic from across the street steps inside and tell them, by a stroke of luck, the part he needed turned up, and their car is all set.

Once again, the “mystic seer” is proven to be right.

Pat is still unconvinced. Don tells her to ask the seer a few questions. She tries to trick the machine, asking if they’ll reach Columbus by tomorrow, even though they don’t plan on driving through Columbus at all.

In response, the seer answers, “If that’s what you really want.”

Question by question, Pat becomes more agitated, more unglued.

“It’s not possible to foretell the future, is it?” she asks.

“That’s up to you to find out,” the machine replies.

“You’re just a stupid piece of junk, aren’t you?” Pat shouts.

The seer answers, “It all depends on your point of view.”

That does it. Pat has had it. She tells Don they need to leave, that he can’t let this machine run his life for him.

He is torn. The machine is predicting his future! How can he just walk away?

His wife implores him. She tells him he can decide his own life. He doesn’t need some penny fortune-telling machine to decide it for him. “I don’t want to know what’s gonna happen,” she says. “I want us to make it happen.” It is up to them to make the most of their lives, to determine the roads and byways they travel along.

Don understands. He gets up, tells the seer they will go where they want to go, whenever they please. He has been freed from the grip of fear and superstition . . . in the “nick of time.”

********************

If there were in fact a “mystic seer” available to me, I might even now know who will win The Eye-Dancers promotion that runs today straight through the holiday season, and into 2015. As it is, it will have to remain a mystery until the promotion ends.

The details of the promotion are simple. Between today’s date and January 4, 2015, if fifty copies of The Eye-Dancers are sold, a winner will be chosen to win a $125 gift card to a retailer of their choosing. Amazon? B & N? A favorite restaurant or department store? The choice is yours.

Beginning today (October 12) and ending January 4, 2015, if you buy The Eye-Dancers, wherever it is sold, in either paperback or ebook format, please notify me–either with a comment on this website, or via email at michaelf424@gmail.com. I will keep track of each person who buys the book during this time frame and then, on Monday, January 5, 2015 , the day after the promotion ends, I will randomly select the winner of the $125 gift card–provided, of course, that fifty copies of the book have sold during the promotional period.

The Eye-Dancers, the ebook, is available for purchase at the following online retail locations . . .

Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/The-Eye-Dancers-ebook/dp/B00A8TUS8M

B & N: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-eye-dancers-michael-s-fedison/1113839272?ean=2940015770261

Smashwords: http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/255348

Kobo: http://store.kobobooks.com/books/The-Eye-Dancers/nKFZETbWWkyzV2QkaJWOjg

And The Eye-Dancers, the paperback is sold at . . .

and CreateSpace, https://www.createspace.com/4920627

Even without the aid of the Twilight Zone‘s “mystic seer,” I hope you’ll take part in this promo!

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

September 27, 2014

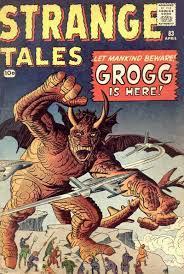

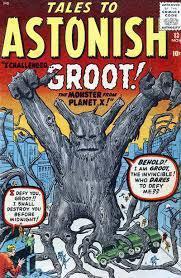

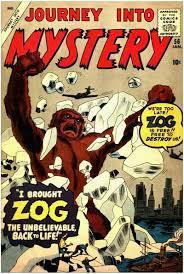

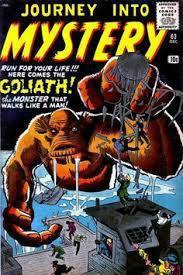

Embracing Your Inner Grogg, Zog, and Groot!

There are so many aspects, so many parts to the process. An idea strikes, giving birth to a story–perhaps it’s a short story that can be crafted in a day; perhaps it’s a novel that will take months, even years to complete. But here, now, at the outset, that’s not important. All that matters is the desire, the need, to write.

It doesn’t take long for that to change, and for the situation to become more complicated. I know, for me, if I have written a short story, there is the initial euphoria of finishing it. A job well done. But now–where to submit it? Will anyone want to publish it? A dozen rejection slips later, a crisis of confidence hits. Who was I fooling? It isn’t any good. Maybe it’s not as polished as I thought–so I go back, edit it some more, and then resubmit to a dozen more magazines. Eventually, I have so many rejection slips and form letters, I can wallpaper my office with them. But I keep submitting, keep believing. It just takes one . . .

And as for the novel . . . multiply the above by a thousand. Whereas the short story is a sprint, a forty-yard dash, the novel is a marathon, a test of endurance. At some point, I know, I will question the entire project. There will come a low point, when energy reserves have been depleted, when ideas hide underneath rocks and behind thick, impenetrable walls, when I ask myself–“Is this story going anywhere? Where do I take it? What do I write next?” Writer’s block, while in the middle of a novel, is a grim feeling. All the work already put forth now appears for naught, stuck in the middle of a chapter that refuses to cooperate.

I had to confront this middle-of-the-story crossroads while writing The Eye-Dancers–the point where the novel will either take off and infuse me with a literary second wind, or die on the vine, withering under a sweltering summer sun, thirsting for ideas that never arrive. For me, and for The Eye-Dancers, this defining moment occurred in chapter 18.

I was slightly more than halfway through the novel, and felt pretty good about what I had so far. But chapter 18 was a quagmire. It was a pivotal chapter, and one of the longest in the novel. I couldn’t seem to get it right–everything I wrote came up flat, like soda left out on the porch all night long. I wrote a first draft–ugh. Lifeless and forced. Reluctantly, bemoaning the wasted effort, I deleted every word of the chapter and began anew. The second draft proved no better. I threw my hands up, literally. Was my concept wrong? Should I take a step back and rethink the whole thing? I remember taking a long walk, thinking, figuring, looking at the impasse from all angles. But nothing came to me. Nothing sounded right.

It brought to mind something George Orwell once said: “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.”

Later that day, at a total loss, I flipped through some of my old comic books, looking for something, anything.

I found it.

**************

When I was in junior high school and began collecting comic books seriously, I never thought I would buy any issues that weren’t superhero-related. The Fantastic Four, The Amazing Spider-Man, The Avengers, and later Batman and Superman were my focus. But as I learned more about the history of the medium, realizing how rich and layered old comics were, I decided to branch out. One of the gems I later discovered was what collectors often refer to as “pre-hero Marvels.”

Prior to The Fantastic Four number 1 (November 1961), Marvel Comics published a small line of adventure and sci-fi comics–certainly not unique in those days. Even DC, creator of Superman and Batman, incorporated a quality line of non-hero comic books. But what made the Marvels special were the monsters . . .

With names like Grogg, Groot, and Zog, just to name a few, these larger-than-life creatures jumped off the page.

I can easily imagine an exuberant ten-year-old in 1960, at the height of the phenomenon, spinning the comics rack at the local corner store, trying to decide which monster-book to plunk his dime on.

The stories, with titles such as “I created Sporr, the Thing That Could Not Die,” were formulaic, silly, and, frankly, ridiculous. But they were magic, too.

What’s more, they were fun.

*******************

That particular day, seeking something of an escape from the writing process, I opened Tales of Suspense number 29 (February 1962). Tales of Suspense is the same title that, ten issues and just over one year later, would introduce the world to Iron Man–but I wasn’t thinking of the Golden Avenger as I flipped through the story, laughing and smiling all the way through “The Martian Who Stole a City.”

The story was dated, predictable, and by no means a masterpiece. But it was just the tonic I needed. It made me feel twelve years old again. It infused me with optimism, a sense of wonder, and it instilled in me a belief that anything was possible, and that any obstacle to creativity can be hurdled and left far behind in a sun-streaked rearview mirror.

Energized, invigorated, I went back to the book, dared to key in the first word of the revised and revised and revised again chapter 18, which expanded to the first sentence and then the first paragraph. Two pages later, I paused, pumped a fist. The logjam had broken. The mind-block had lifted, disintegrated, like smoke on the wind.

It was a necessary reminder that, no matter what our Amazon sales ranking, no matter what or how many reviews we have, no matter how hard it sometimes is to get our thoughts and visions onto the page, when it’s all said and done, we are doing something we were born to do. Something we need to do. Something we love.

Ray Bradbury once wrote, “Zest. Gusto. How rarely one hears these words used. How rarely do we see people living, or for that matter, creating by them. Yet if I were asked to name the most important items in a writer’s make-up, the things that shape his material and rush him along the road to where he wants to go, I could only warn him to look to his zest, see to his gusto. . . . For the first thing a writer should be is–excited. He should be a thing of fevers and enthusiasms.”

As I continued to type, the words now pouring out of me like lava, the classic issue of Tales of Suspense number 29 still lay there, in full view, on my desk.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

September 12, 2014

The Greatest Distance Is Only a Thought Away (Or, A Morning on the Beach)

I have always loved the sea. From the first time I experienced an ocean beach, I felt drawn to it, its vastness, the steady rhythm of the waves, the sounds and smells and textures. Growing up in Rochester, New York, hundreds of miles from the Atlantic coast, I didn’t have the chance to visit the sea very often (though Lake Ontario is a pretty fair facsimile!). And so, whenever my family would take a trip to the coast, I always looked forward to it, counted down the days. The trips never disappointed.

But there was one trip, one particular experience, that stands out, apart from the rest.

It was midsummer 1994, and my family and I took a two-week expedition to Prince Edward Island, Canada–to this day, the most beautiful place I have ever seen. We toured the Island, took in the sights, the rich red dirt roads and farms and quaint seaside villages. But most of all, we went to the beaches. PEI is famous for its beaches. We stayed at a hotel right by the shore.

One morning, at dawn, I woke up. I don’t know why. I just felt an urge to get up early and experience the day. Everyone else was still asleep. I quietly let myself out of the hotel and walked down the narrow footpath, through grasses still moist with dew. Off to the left, a raven, an early riser himself, pecked at something in the grass, ignoring me. I continued on to the beach, empty at this hour, as the sun began its ascent in the east.

I walked along the beach, my feet making patterns in the sand, down to the water’s edge. A gull flew overhead, calling out, perhaps demanding a scrap of food I didn’t have. The water was warm as it flowed over my feet and around my ankles–just another of PEI’s many charms. Despite its northern location, the ocean water surrounding the Island is the warmest anywhere along the Atlantic coast north of Virginia.

The waves were gentle that morning, the breeze blowing in softly off the water. I looked out, as far as I could see. The sky was some nameless variant of pink, the sun rising, slowly, steadily, the start of a new day. Another gull–or perhaps it was the same one–squawked again, its call echoing, echoing.

I peered at the horizon. It was hard to tell where the sea ended, and the sky began. It all appeared to be joined somehow. Not separate, but whole. Not two, but one. That’s when it happened . . .

I suddenly felt something, I wasn’t sure what. It was a jolt, like a surge of electricity, but it was also airy, gentle, a feather swaying, nearly weightless. I closed my eyes, opened them, and I saw.

I saw, in my mind’s eye–so clearly it was as if I were seeing it directly before me–a distant beach across the water. It was hours later there. People were milling about. And some of them were looking to the west, looking toward me. Maybe they, too, were feeling something above and beyond themselves.

***********************

In The Eye-Dancers, Mitchell Brant, Joe Marma, Ryan Swinton, and Marc Kuslanski travel through the void, whisked to a parallel world through an unexplainable psychic connection with the “ghost girl” who haunts their dreams. While Marc, ever the rational scientist at heart, attempts to explain their remarkable situation through the principles of logic and quantum mechanics, Mitchell–inquisitive by nature, intuitive, with an imagination constantly in overdrive–believes there is much more to it than the laws of physics can explain.

And yet, he, too, wants a reason, something to grab hold of, something that might begin to explain why this happened, how this happened, and how Monica Tisdale, the “ghost girl,” was able to draw them into her universe.

At novel’s end, when she once again walks in the shadows and secret places of his dreams, Mitchell asks her, point-blank . . .

“Why did you ever come to me in the first place? We . . . I . . . don’t even live in your world.”

To which Monica Tisdale answers, “I never really picked you. I didn’t say to myself, ‘I need to get Mitchell Brant to help me.’ I just called, and you were there.”

But Mitchell needs more than that. It’s not good enough, doesn’t go far enough . . .

“‘But the distance,’ he said. He couldn’t even fathom it. The void. The gulf. ‘You and me, we’re so far apart.'”

“‘Are we, Mitchell?’ she said. ‘Are we really?'”

Later, upon reflection, in his own words, Mitchell states . . .

“Maybe more than anything, I learned that everything’s connected. . . . I’m not sure how I can explain it to make sense. It’s like, even the things that seem so far away you can’t even imagine . . . even those things are right there with you. And the people, too.

“Maybe we’re all connected to each other, in ways we can’t even really understand. And that’s okay, I guess. Because maybe we don’t need to understand it.

“We just need to believe it.”

**********************

Standing on that beach along the sandy shores of Canada’s garden province, the sunlight warming the morning air, I felt a part of the whole, as if a million invisible fibers extended from me, in all directions, everywhere, across the expanse of the globe. I thought of the fish beneath the water, miles offshore, swimming, pursuing, surviving. I thought of giant squid and crustaceans and blue whales, slicing through the water like living, breathing ocean liners, and blind, glowing creatures with fangs and stings, as yet undiscovered by humankind.

Looking across the surface of the waves, their rhythm timeless, eternal, I thought about the continents on the other side. What were people doing at this moment? And I realized–everything. Babies were being born in London, Moscow, Johannesburg, and Rome. Somewhere in Berlin, there was a car crash; elsewhere, there was an unexpected visitor popping in unannounced, perhaps a long-lost son returning home and bringing smiles to his parents’ faces. In Ankara, in Casablanca, in Madrid and Paris and Warsaw and every town and village and hamlet in between, life was happening. People laughed and cried, some shared and felt good; others were alone, in run-down apartments or dark alleyways, thinking of surrendered choices and opportunities now irretrievably lost.

Here I was, standing by myself on a fine Island morning, the sea and the wind and the gulls my only company, and yet–I was everywhere, plugged in, one small cog in an infinite and incomprehensible machine.

The gull squawked again, as if acknowledging my thoughts, and then another gull swooped in low, and then another, and another.

I watched as, moments later, they flew out over the water, becoming smaller and smaller, until they vanished, like a sea mirage.

It was then that I heard voices. Other early risers were coming now, the beckoning of an Island summer day too much to resist.

The spell broken, I turned around and headed back for the hotel.

As I walked, I thought of sandy beaches halfway around the world, fish that swim in the dark, and stars that shine, like diamonds, in the night sky. I realized, the light from some of those stars, distant beyond imagining, takes millions of years to reach our planet.

Yet reach us it does.

Thanks so much reading!

–Mike

August 28, 2014

A Trip Back Home, a Paperback, and a Promotion

I can still remember the first time.

I was seven years old. I don’t remember the shop, or even what kind of shop it was–a bookstore, perhaps? A drugstore? An eclectic little gem with knickknacks and mementos gracing dusty, wooden shelves? I don’t know. That detail has escaped, leaking through the holes of conscious memory, a magic trick of the mind. But the rack, the spinning rack–I remember that.

The rack was taller than I was, filled with issue after issue of comic books. The covers promised grand adventures, larger-than-life stories, journeys through space and time. I spun the rack, mesmerized by the squeaking sound it emitted, the covers whirring past in a blur.

When the rack finally stopped spinning, I looked at the comic book directly in front of me. The Fantastic Four, number 209. I’d heard of Marvel’s first superhero team, of course, but I was also aware that my older brother, who collected comics, thought they were overrated. He was Spider-Man fan. But the scene depicted on the cover carried my seven-year-old mind far away, up high, soaring with the stars and comets and planets from galaxies so remote I couldn’t even fathom the distance.

I knew I had to have that issue.

The rest, as they say, is history. That single issue of The Fantastic Four began a lifelong love of science fiction, comic books, and, really, stories of all sizes, shapes, and genres. I wrote my first short story that fall. I began to read more and more for the sheer fun of it, not simply because it was assigned for school. A handful of years later, I was introduced to the world of Ray Bradbury, as I lost myself in stories of carnival rides and astronauts, time travelers and Martians. High school dawned, and I read Shakespeare, Bronte, Dickens, and Steinbeck. When college arrived, it didn’t take long for me to declare a major–English.

My life has always revolved around books. The feel of them, the texture of the pages as you turn them. The musty, magical smell of a comic book from 1952, an artifact, a relic from a bygone era. Boys with cameras or baseball gloves smile at me from advertisements sixty years old, spanning the chasm of decades, infusing me with a sense of nostalgia for a time period I never even experienced or saw.

The physical presence of books–the weight and heft of the volume–these elements add to the experience. Reading a book, an actual, physical book, is different from reading its equivalent online or on a Kindle or smartphone. Not necessarily better, just different. More complete, perhaps, engaging more of the senses, providing for a more intimate and personal experience. “There is no friend as loyal as a book,” Hemingway once said, a sentiment I have often shared over the years.

And so it is with great excitement that I can announce–The Eye-Dancers, published as an ebook late in 2012–is now also available as a paperback. It seems fitting that the publication of The Eye-Dancers in hard-copy form should happen now. This weekend, I head back home to Rochester, NY, visiting the old house where I grew up; the house where I learned to love books, not just for the stories, but for the characteristics themselves–the binding of the spine, the wrinkles and imperfections, the crisp, fresh smell of new editions, or the heady aroma of decades-old volumes, the yellowing pages succumbing to the oxidation and literary alchemy of time.

I’ll bring a physical copy of The Eye-Dancers with me to Rochester, I’m sure. And perhaps, at some point, some quiet, still moment, I’ll wander into my old bedroom, open the book, and remember . . .

******************

The Eye-Dancers, the paperback, is available for purchase . . .

and at CreateSpace, https://www.createspace.com/4920627

Additionally, The Eye-Dancers, the ebook, is now on sale for just 99 cents, through the end of September, at the following online retail locations:

Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/The-Eye-Dancers-ebook/dp/B00A8TUS8M

B & N: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-eye-dancers-michael-s-fedison/1113839272?ean=2940015770261

Smashwords: http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/255348

Thank you to everyone for all the wonderful and ongoing support!

And thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

August 15, 2014

It’s Magic!

“Pick a card, any card,” he said, and winked.

I went for the top card on the deck, but pulled my hand back. That would be too easy.

“Crafty,” he said, smiling. I shrugged. I was twelve years old, and this was the first time I’d ever met him. “Cousin Ed,” we called him. He was actually my grandmother’s cousin–I wasn’t even sure what that made him to me. I just knew he was fun, lived in Boston and spoke with an accent so thick you could hear the chowder coating each syllable, and loved to perform card tricks.

“C’mon, Mike,” my oldest brother said. The entire family was gathered around the table. It was a warm, humid evening in late July, the windows opened, the metallic hum of the cicadas and the steady, thrumming chorus of the crickets filtering in. “Will you pick a card already? Geez! This isn’t exactly rocket science here.”

Cousin Ed laughed out loud at this and tapped on the deck. “Listen to your brother,” he said.

I picked a card near the bottom of the deck.

“Okay, now show everyone here your card,” Ed said, “except for me, of course.” My mother and father, brothers and sister moved in close as I showed them the card. It was the seven of diamonds. It’s funny–the things you remember through the years. I have forgotten so many things–countless details that have evaporated from my conscious memory like smoke on an autumn wind. But I remember the seven of diamonds . . .

Ed held out the deck, cutting it in two and shielding his eyes for effect. “Kindly put the card back,” he said.

I did, and faster than the eye could follow, he slapped the deck back together and began to shuffle. He shuffled like no one I had ever seen, his hands a blur, his fingers maneuvering, redirecting, reconfiguring. We all knew we were in the presence of a master of his craft. He made the hyper-speed shuffling look easy.

This went on for over a minute. And then, finally, Cousin Ed placed the deck, facedown, on the table and tapped the top card.

“Turn the top card over if you would, my good man,” he said. But it wasn’t the card I had chosen. “Darn!” Ed said. “Guess I must’ve tapped the deck too hard.” “Hard” came out “hahd,” the “r” silent, the chowder sticking to the word, rich and thick like paste.

He tapped the deck again, then turned it over, revealing the bottom card. “Now I know that must your card,” he said.

I shook my head, and my sister snickered behind me.

“Hmm.” Ed rubbed his chin, then fanned the deck, face-up, along the surface of the table. He rubbed his chin harder, thinking, frowning, and then reached for the seven of diamonds. He said nothing as he held up the card; he just smiled. The smile said it all.

“How . . . ?” my brother said.

Ed bowed, smiled wider. “It’s magic,” he said.

Later, I had a moment with Cousin Ed alone. I asked him, point blank–how had he done it?

He told me it was all in the sleight of hand, the art of shuffling, the showmanship and banter, and, most important of all, making the audience’s eyes follow where he wanted them to go. “It’s not much of a trick, once you know the secret,” he admitted. “That’s how tricks are. It’s the not knowing that makes them magic.”

I didn’t want to hear that, and again urged him to show me how he’d done it.

“Aw, why not?” he said. “Not sure when I’ll be out here visiting again. But I’m tellin’ ya, you’re gonna be disappointed . . .”

And when he was through, when the dense morning fog had rolled out to sea, replaced by the clear, bright light of day, I realized he’d been right.

The trick had lost its luster.

The magic was gone.

*************************

There are many details authors must account for in a single novel. Events that occur in chapter two reverberate throughout the story and affect the goings-on in chapter twenty-six. Characters grow and evolve. Twists and turns arise, unexpectedly, sprinkled in as if by mischievous literary elves intent on leaving their pixie footprint on every page.

And sometimes, especially in science fiction and fantasy–but by no means limited to speculative fiction–the unexplainable happens. Time warps occur. A series of deja vu moments takes place for the protagonist that somehow seem connected–but to what? And when? And where? Or, as the case may be, mysterious little “ghost girls” with swirling blue eyes haunt the dreams of seventh-grade boys and open portals to other, distant dimensions.

Much to Marc Kuslanski‘s chagrin, the endless blue void in The Eye-Dancers; the strange psychic connection the boys share with Monica Tisdale, the “ghost girl”; and the extent and methods of her paranormal abilities are never explained. They are hinted at, lived through, coped with . . . but never explained.

I debated this as I wrote the novel. Should a coherent, logical (or perhaps even pseudo-logical) bow tie of an explanation be given? Should the unexplainable, in fact, be explained? What would be gained if it were? What would be lost?

There was a moment during the writing process when I thought back to old Cousin Ed and his card trick, the way I had felt, like a pin-pricked balloon, when he shared the secret with me. And I knew the approach I needed to take.

Granted, Marc, always the scientist at heart, tries to explain everything that happens, using quantum theory as the bedrock of his analysis. But the novel never fully confirms, or refutes, his conclusions. Perhaps some of them are correct. And perhaps others are 100% wrong.

It is left for the reader to decide.

******************

After Cousin Ed returned to Boston, I was determined to learn how to shuffle like a pro so I could perform his card trick when school opened in the fall. I spent hours that summer practicing, and on the first day back to class, I made sure to bring a deck of cards with me.

At lunch, with several students watching, I whipped out the deck, asked for someone to pick a card. Any card.

When it was over, I had achieved the desired end result. I wasn’t nearly as skilled as Ed, but the performance was good enough to mystify and confound. My friends asked, “Hey, how’d you do that?”

I shrugged, smiled.

“It’s magic,” I said.

And no matter how many times they asked, I never did reveal the secret.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

July 31, 2014

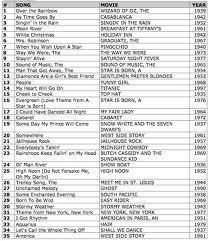

Pausing for a Look–Over the Rainbow

So . . . which scene is it for you?

The tornado sequence, perhaps, filmed in atmospheric black-and-white, and no doubt the cause of countless nightmares for young children throughout the decades?

Or maybe it’s the magical moment when Dorothy first enters Oz, as the monochrome of black-and-white suddenly gives way to a vibrant palette of color.

Not quite, you say? Then how about the legendary Wizard of Oz himself being exposed for the fraud he is, hiding behind the curtain?

But of course, who can forget the Silver Screen’s most iconic villain, The Wicked Witch of the West, melting away? “I’m melting, I’m melting!” is such a famous line, it has been mimicked and re-created many times over on both stage and screen in the years since.

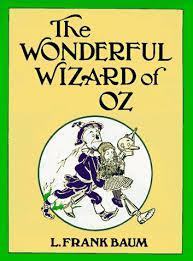

Indeed. There are many unforgettable scenes in The Wizard of Oz–arguably the most beloved motion picture in Hollywood history. There are so many such scenes in the 1939 classic, based on L. Frank Baum’s novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, that, at first blush, it may seem impossible to choose just one as a favorite.

But for me, there is one sequence from the movie that stands apart, not only as my favorite scene in The Wizard of Oz, but one of my favorite scenes of all time, anywhere, from any film or TV show–the “Over the Rainbow” scene, featuring the film’s heroine, Dorothy Gale, and her dog, Toto. The irony is–the sequence was very nearly removed during the cutting process.

Perhaps that’s because it doesn’t depict houses flying in the wind, witches soaring through the night on broomsticks, or cowardly lions and tin men and talking, walking scarecrows.

The “Over the Rainbow” scene occurs just five minutes into the movie. Studio executive Louis B. Mayer and producer Mervyn LeRoy both thought it should be deleted because, they argued, it “slowed down the picture.” If not for the sturdy resistance on the part of others associated with The Wizard of Oz, “Over the Rainbow,” the signature song of Judy Garland’s career, most likely would have withered and died.

After Dorothy is unable to get her aunt and uncle to listen to her about an unpleasant run-in she and Toto had (“Find yourself a place where you won’t get into any trouble,” her aunt snaps), she wanders off into the barnyard, loyal Toto at her side.

“Some place where there isn’t any trouble,” Dorothy muses. “Do you suppose there is such a place, Toto? There must be. It’s not a place you can get to by a boat, or a train. It’s far, far away. Behind the moon, beyond the rain . . .”

And here she begins to sing of a place “over the rainbow way up high,” where all your “troubles melt like lemon drops.”

It must be pointed out that Mayer and LeRoy were right about one thing. The “Over the Rainbow” sequence does in fact slow the picture down. I would argue, however, that this effect makes The Wizard of Oz a better movie, and a far more memorable one.

*******************

When the adrenaline rush and creative maelstrom of a novel’s first draft gives way to the laborious and painstaking process of revision and rewriting, we often delete far more than we add. And that’s the way it should be. In his memoir On Writing, Stephen King suggests authors should be able to cut at least 10 percent of their total word count from a first draft. First drafts are generally padded, bloated things, gorged and made fat with too much description, too much repetition, and chock-full of sentences, paragraphs, entire scenes just begging to be tossed into the pit of discarded excess.

It’s natural, when trimming the bulging waistline of a first draft, to look for scenes that slow down the action of the story, that seem to lack relevance or that do not advance the plot. And most of the time, such scenes should indeed go. But sometimes . . . yes, sometimes, there are exceptions.

The Eye-Dancers, for example, is a novel told through the point of view of four main characters–Mitchell Brant, Joe Marma, Ryan Swinton, and Marc Kuslanski–and one of my primary goals when I wrote the story was to enable readers to get into the mind of each character, get to know him, and, hopefully, root for him. There are several “slower” scenes where the boys talk among themselves or where one of them wanders off by himself to think, ponder over his problems, and try to figure out his place in the universe.

While it’s true action sequences and scenes that serve to advance the plot should and do reveal aspects of character, they cannot capture the thoughts, fears, aspirations, dreams a character might have in a quieter moment. Nor can they portray an everyday scene, where we can witness the characters interacting over events that are mundane and normal as opposed to earth-shattering. Without such scenes, little islands of stillness amid the roller-coaster ride of action, intrigue, and death-defying chase sequences, we cannot pause long enough to know and like (or dislike, as the case may be) each character over the course of the story.

***************

When the forward momentum of The Wizard of Oz pauses, just long enough for Dorothy to sing “Over the Rainbow,” we as the viewers are introduced to one of the primary themes of the movie–magic, fantasy, the promise of a place far, far away bursting with color and life and sights to stir and astound the senses. We get a foreshadowing of Oz itself, of the quest Dorothy and her friends-in-waiting will undertake.

And, perhaps most important of all, we get a glimpse of the girl herself. We share in her dreams, her wishing upon a star if you will, her ability to see and imagine beyond the nondescript reality of her daily life.

This was not lost on history. On June 22, 2004, sixty-five years after The Wizard of Oz debuted in theaters and exactly thirty-five years removed from Judy Garland’s death, the American Film Institute voted “Over the Rainbow” as the greatest movie song of all time.

So the next time you’re sweating over the edits of your second draft and are all too eager to cut a scene that does not push the action along, take a breath, read it again, and reconsider.

Maybe, just maybe, the scene in question will transport your readers to a land “heard of once in a lullaby,” where “happy little bluebirds fly.” where the “skies are blue,” and “the dreams that you dare to dream really do come true.”

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike