Michael S. Fedison's Blog, page 14

October 1, 2015

The Wormhole of Our Dreams

“Peering out his bedroom window, his eyes flattened into squinting slits, Mitchell Brant saw her.”

So begins The Eye-Dancers, but is this episode merely a dream or is it real? Or is it, in some strange, inexplicable way, straddling the sorcerer’s tightrope between the two worlds, with one foot in each?

This of course begs the question: What are dreams, anyway? And should we even preface references to them with innocuous terms like “merely”?

Marc Kuslanski, for one, would certainly answer with a resounding yes. Or, knowing Marc, he’d probably say, “affirmative,” but that is neither here nor there. Logical to the core, unwilling to grapple with the mystical or the unexplained, Marc believes that dreams are nothing more than a biological function, a by-product of sleep.

“We’re beings of electrical current, pure energy,” he explains in chapter four. “While we’re in our sleeping state, the brain needs something to do. It gets bored. So, it manufactures stories, adventures, even nightmares. It’s like a prisoner in solitary confinement. Nothing going on. No outside stimuli. So you need to create your own entertainment. That’s all dreams are, you know. Just the brain–your brain–killing time.”

Mitchell Brant, Joe Marma, and Ryan Swinton, Marc’s target audience for his mini-dissertation, don’t agree. They’ve each dreamed of the “ghost girl” three nights in a row (the reason they ask Marc’s opinion on the subject to begin with), and are convinced the dreams have significance. More than once, over the course of The Eye-Dancers, the characters are struck by the fine line that separates our dreams from our actual lives–to the point that they start to question where the one begins and the other ends. I suppose that’s a line we’ve all wondered about, at one time or another.

I’ve certainly had my share of dreams that have caused me to take a step back, examine, and delve into the heart of the matter. And I remember the day–a snowy, frozen January afternoon with the wind slamming into the house, the eaves whining in protest, the world a white snow globe, the flakes swirling, blotting out the yard–when my older brother told me about dying in dreams . . .

“You never see yourself die in your own dream,” he said. “Am I right? Or am I right?”

I looked at him, shook my head. He was wrong. There were multiple dreams I’d had, nightmares, where I knew I would die . . .

“But you didn’t see yourself die, did you?” he persisted. “You didn’t feel your heart stop. Didn’t feel the fangs gash into your neck. I bet you woke up right before it happened . . .”

I didn’t answer. It was as if he were inside my own head. He had nailed it to a T. Outside, a stiff gust of wind rattled the windows, invisible fingers seeking entry into the house, an escape from the cold.

“If you actually did see yourself die in your dream,” my brother went on, “we wouldn’t be having this conversation right now. When you see yourself die in your own dream–and I mean, really see yourself die, not wake up a second before you do–you really will die. Your heart’ll just stop, right there in your bed.”

“That’s dumb,” I said. “I mean, how could anyone know that for sure?”

“Ask around,” he said. “You’ll see.”

I did ask around, and eventually I realized my brother’s theory wasn’t rock-solid unassailable truth. But it stayed with me anyway, perhaps triggering a lifelong fascination with dreams–a fascination shared by many others. Dreams have been studied, speculated about, hypothesized, diced, sliced, and spliced for millennia, and surely, a thousand years hence, the field of oneirology will still be going strong. People want to know, have always wanted to know–what do our dreams mean? What do they represent?

Have you ever experienced such an unusual dream–not necessarily even a bad one–that, upon waking, you couldn’t help but ask yourself, “Why in the world would I ever dream that? Why would I even imagine something so completely bizarre?”

The rapid scene changes. The helter-skelter quality of the “stories” that unfold. The themes and dangers and desires that define the world of our dreams. What should we do with them? Anything? Or do we blissfully ignore them, relegating them to some neat, locked box, to be opened only when needed in passing–perhaps to amuse a dinner guest or scare a friend or impress a date–but never to be explored in depth, or grappled with in any meaningful way?

Maybe we tend to push our dreams to the background because, well–how else should we respond? We can’t let them cripple us or hinder us in our everyday lives. Perhaps more than that . . . even after all these years, all the scientific advances and data and studies, dreams remain elusive. No one can say, unequivocally, what they mean and why they occur. The answers are likely broad and layered anyway, dependent on the individual person and the individual dream in question.

Are dreams moving symbols, manifestations of our fears, needs, desires, memories, goals? Are they gateways to previous lives or vehicles for predicting the future? Could it be that they provide us with glimpses into the multiverse, our assorted lives sprinkled throughout alternate realities and dimensions? That they are, in effect, another version of reality and not actually “dreams” at all?

“You know what it felt like,” Mitchell Brant says shortly after he and the others have traversed the void and find themselves in the alternate-world town of Colbyville. “When she was in our dreams, it felt real.”

Who knows–maybe we even have it all upside down. Maybe, just maybe, there is another version of ourselves, somewhere, who, every night, “dreams” our lives here on earth, our days unfurling strand by delicate strand in the mind of our counterpart while they sleep. And maybe, while we are asleep, we, in turn, “dream” their lives for them–the two intersecting, interweaving, forever linked . . .

. . . in the wormhole of our dreams.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

September 10, 2015

(Not) A Day at the Beach

I sat in the chair, the gray, metallic surface hard and cold and unforgiving against my back. I rested my elbow on the small wooden desk attached to the chair’s right arm, my legs moving in restless spasms, up and down, side to side, as I waited.

The time had come. All of my preparation, the writing completed over the summer, had been accomplished with this moment in mind.

Would they like my story?

I felt reasonably confident sitting there. I had completed four short stories ahead of the semester, and, the previous week, at the end of the first class, I had handed out the one I thought was the most polished. It was titled “A Day at the Beach,” and I’d gone over it with the proverbial fine-toothed comb, sharpening themes, honing the focus, cleaning up the prose.

Even so, there were some very real nerves. This was my first-ever graduate-level writing workshop, after all. My classmates, about fifteen in all, were talented wordsmiths, and no doubt some of them were veterans of previous workshops–not rookies like me.

Two other intrepid souls had shared their stories with the class as well, and theirs as well as mine would be critiqued thoroughly over the course of the next couple of hours.

Whose story would be put to the test first?

The professor, a bald, bespectacled man in his late fifties with a thick British accent, announced, “To get things started, we have Michael Fedison’s ‘A Day at the Beach.'”

So much for that question!

My legs grew more restless as the professor called for someone, anyone, to get the critique under way.

A blond, bearded guy named John was all too eager.

“I began this story, and I didn’t really find what motivated this character to do the things he did,” he said, thumbing through the pages of his printed copy. “I kept waiting for that to change, for something to happen to show me something. But it never did.”

Ugh. I felt as if I’d been punched in the solar plexus.

To back up, all throughout the previous week’s class, the professor, in a sort of introduction-to-creative-writing lecture, had discussed the all-important function of character in storytelling. As I listened, I grew a bit concerned–not because I disagreed, but because “A Day at the Beach,” the copies of which were printed out and sorted in a stack at my feet, ready to be distributed to the class, was the exception to the rule. It was a theme-based story, attempting to tackle social mores, group psychology; and, packed within its dozen pages, I had tried to delve into big issues that affected us as a culture and world.

It was not in any way a character-driven story. Looking back now, I can clearly see the problems this presented. Lacking any real character development, the story needed to be a slam dunk in every other aspect to succeed–and even then, its impact would be muted. At the time, though, on that warm September evening deep into the 1990s, I hardly thought that mattered. Surely, the other students in the class would see the themes jumping off the page, and an intriguing discussion of said themes would emerge.

That’s not the way it happened. John’s opening salvo had broken the literary ice, and several of the others began to chime in.

One young woman, whose name I’ve long since forgotten, pointed out that the prose style was arrogant, and she felt talked down to as she read the story. Another student said she couldn’t follow the plot and agreed about the writing–it seemed forced, she said, awkward, the words self-conscious and without flow. Still another complained that “A Day at the Beach” had no forward momentum, no thrust that wanted to make him turn the page. It just sat there, flat and lifeless as a suffocated fish.

By this time, when I wished a hole would open up in the floor beneath my chair and swallow me, the professor asked me to explain my story, to discuss what I had wanted (and obviously failed!) to accomplish with it.

And that’s what I did. I talked about the different scenes, the character’s reaction to the events, even his name, all of which were symbolic. When I was finished, I felt a little better. Some of the students nodded and seemed a bit more receptive to the story than they had upon reading it. But it was a Pyrrhic victory. If I had crafted the story in the most effective manner, I wouldn’t have needed to explain it to the class. It would have explained itself, without any postscripts from me.

When I drove home that night, I felt beaten, defeated. I didn’t turn on the radio. I just drove in silence.

I wondered if perhaps I’d made a big mistake taking this class.

More than that, I wondered if I was really cut out to be a writer.

**************

In The Eye-Dancers, Ryan Swinton fears rejection more than just about anything else in the world. A class clown of sorts, when he tells a joke, he needs for others to laugh and enjoy the punch line.

As writers, we’ve all been there–and I’m not sure if it’s something we ever fully overcome. Is there anyone among us who is completely and unequivocally immune to reader response? We toil and we labor and we plot and we live and breathe through our characters . . . and then we share our work.

And when we do, no matter how much praise we garner or positive feedback we enjoy, it is also inevitable that we will receive criticism. It might come via a scathing remark from a friend or even family member, an angry email, or a negative review. The question is–when the critical words come, and they will–what do we do with them? Do we get angry? Do we ignore them, blissfully unconcerned? Do we take them to heart and begin to doubt our worth as a writer? Do we disregard the ninety-eight positive reviews and fixate on the two negative?

Perhaps, as with so many things, there is a happy medium, a middle path. Some criticism, after all, is valid, and should be weighed and considered. When students in that creative writing workshop said “A Day at the Beach” suffered due to a lack of a strong lead character, they were right. I would have been foolish to ignore that.

Other criticism, however, might not be valid. Overly general, vitriolic, or irrelevant critiques, while they may scald, can justifiably be ignored. How to discern the difference between sound, reasonable criticism that prods and encourages you to be better, reach higher, and hone your craft and critiques that offer little more than insecurity-inducing doubts that offer nothing of value can, admittedly, be a tricky and difficult task. The only way I know how to attempt it is to try to detach myself emotionally as much as possible and apply the criticism to the story as if the story had been written by someone else. With an objective eye (or as an objective of an eye as I can hope to attain under the circumstances!), I can then better digest the critique in a thorough and neutral manner and either learn from it or disregard it.

That’s easier said than done, of course–just one more aspect of the writing trade that is more art than science.

But whatever we do, it’s important to remind ourselves why we write to begin with–why we log the long hours, the writer’s block, the struggles, the joys, the failures, and the exhilaration of the creative process.

We have passions and loves and fears and longings that need to be expressed. We have words inside of us that must be poured out, calling, prodding, kicking, screaming to be let loose onto the page.

And we have a desire–no, more than that, a need–to share those words with others.

*************

I handed out two more short stories in that creative writing workshop. Neither was as well received as I’d hoped, but both represented progress over my first attempt. The feedback, though highly mixed, grew more positive with each effort, and by semester’s end, I was determined to keep at it, to keep trying, keep writing.

Sometimes the writing process is exhilarating, a mountaintop experience like no other; sometimes it is exhausting, draining, stripping you to the core. But it’s what I love. It’s what I am, and what I do.

Even if it isn’t always “A Day at the Beach.”

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

August 22, 2015

Writing What You Know (Or, Reading in Front of the Sixth-Graders)

“I think you’re ready, Michael,” she said. “You’re reading very well, and I want the big kids to hear it.”

On the one hand, I was thrilled. Of all the students in the class, I was the one Mrs. Northrup had chosen for the honor. But on the other hand, I was scared silly. I was six years old that fall, a first-grader who may have been reading well but who was also the shyest student in the class. Looking back, I am sure Mrs. Northrup realized this, and she had decided the task assigned would do me good.

Of course, being six, I didn’t share her professional and experienced perspective. She’d been a teacher for decades. I just knew that standing up in front of a classroom full of older kids and reading aloud to them seemed about as beneficial for my development as walking straight into the heart of an active volcano.

“Don’t worry,” she assured me. “You’ll do just fine.”

When the time came, book in hand, I trudged through the old hallways of Abraham Lincoln Elementary School, up the flight of stairs to the floor where the “big kids” had their classes, and, moving slower and slower with every step, arrived outside the assigned door. I wished Mrs. Northrup had accompanied me. She could have introduced me to the class, or done or said something to make it easier. But she had sent me up by myself.

I considered turning around and leaving, but realized Mrs. Northrup would get word of such a tactic before day’s end. No. I was stuck.

I knocked on the half-opened door, my heart beating faster, faster. There were sixth-graders in there! They seemed light-years ahead of me, and more intimidating than a pride of lions. The teacher–whose name I have long since forgotten–smiled at me and motioned for me to come in.

“You must be Michael,” she said. “Mrs. Northrup told me to expect you, and I was just telling the class that one of the top first-grade students would be coming up to read.” Great, I thought. More pressure. “Come along in!” she beamed.

I stood in place a moment longer, my mind still clinging, stubbornly, to potential escape routes. But when the teacher motioned for me to come in again, her smile widening, I did the only thing I could think of.

I turned my back to the class, took a deep breath, and sidled through the door. I heard someone in the class chuckle, but I didn’t turn around, wouldn’t turn around. In front of me, the blackboard still contained the teacher’s notes, in crisp, perfect chalk-script, from whatever lesson the class had been learning earlier that day.

No one said a word. I looked at nothing but the chalkboard–I didn’t dare glance back at the class, nor did I look at the teacher. I had a job to do, a task to complete, and I didn’t want to be in any way distracted.

I opened the book to the assigned spot, and began to read. The passage ran one entire page. I wasn’t sure the class could hear me with my back turned to them, but I didn’t stress over it. I just told myself to read the next line, the next sentence, the next paragraph, get through it, and then exit the room.

As soon as I read the last word, I began to side-walk toward the door. I moved as quickly as I could, and I didn’t turn around and walk face-forward again until I was in the hallway, heading toward the stairs, which would take me away from the sixth-graders and their classrooms and their lessons.

Not once, during the entire experience, did I turn to face the class.

*********************

It’s something every writer has heard, often drilled into them with the force and repetition of an iron-clad commandment: “Write what you know.”

We hear this so many times, in so many different places, and from so many reputable sources, it seems nearly impossible to argue. After all, who can argue against the truth? Besides, the advice seems to hold a lot of weight. When we write about experiences, situations, jobs, relationships we have experienced, don’t our words contain more validity? Don’t they resonate more, sing louder and more confidently?

Yes.

And no.

Let’s take a step back. What, exactly, does “write what you know” refer to? Is it to be taken rigidly, literally, basically saying that if I have never been fired from a job, to use a simple for-instance, that I cannot then write about a character in a story who is fired from their job?

Or is it more broad? Maybe, though I haven’t ever been fired, I still can imagine what such an experience might feel like. Perhaps I have been dropped from a sports team, turned down at an interview, caught doing something wrong at home that resulted in less-than-ideal consequences. The feelings I may have experienced during those situations may not be identical, one-for-one matches to getting fired, but do they really need to be?

Or take my first-grade experience related above. It’s a silly old story on the surface. (And that evening, after getting word of what happened, Mrs. Northrup called my mother on the phone to tell her all about it. They both had a good laugh over it, and eventually I did, too.) But the experience also contains a lot of very real, raw emotions: the fear of public speaking; feeling awkward and shy; the fear of performing badly under pressure; the possibility of being laughed at, ridiculed, or rejected; the burden of carrying the expectations of my teacher to represent her class well; the isolating journey up to an unknown, Brobdingnagian portion of the school, inhabited by “big kids”; and so on.

In other words, it is rich with emotional experience, feelings, internal memories that can be “borrowed,” so to speak, when writing about situations that, at first glance, seem radically different and unrelated, but, in actuality, when you probe deeper and drill down to the feeling level, are really quite similar. After all, what do we remember from our experiences, the good ones as well as the bad ones? The circumstances, obviously, but even more so, the feelings, the emotions, the pain or joy, the sadness or elation that resulted.

Writing what you know can be interpreted as only writing about things that are a one-for-one match with your own personal experience. That is a valid interpretation. But I would argue it is an unnecessarily constricting one. A fiction writer uses his or her imagination to create worlds, events, characters that, hopefully, allow readers to enter into the story, become engaged in far-off places, other time periods, or even just the next town over. If we as authors are reluctant to write things beyond the purview of our own literal experience, then we probably should not write fiction at all. With such strict parameters in place, creating a straitjacket on our literary endeavors, speculative fiction would never exist. There could be no time machines or werewolves, vampires or interdimensional voids that carry four seventh-graders to a faraway and alien world. There could be no Yellow Brick Roads or dreams and powers that lift us high up, “over the rainbow.” There could be no Morlocks or Superman or preternatural do-overs in Frank Capra Christmas classics.

Anytime I feel disqualified from writing a certain scene or character because I “haven’t ever done that before” or “been there before,” I just take a moment and think back to that scared, shy, and overwhelmed first-grader. If I just close my eyes and listen, really listen, I discover he has so much to share.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

August 6, 2015

Nothing in the Dark

It can be anything, really . . .

A sense of dread at the thought of standing up in front of a room full of strangers and delivering a speech.

A heavy, sickly feeling that grabs on tight and doesn’t let go whenever you think of that annual performance review or that interview for a new job.

A sense of doubt so severe, it causes you to sweat and second-guess and procrastinate when confronted with a certain nausea-inducing task.

The list can go on and on, scrolling through the virtual pages of our minds, memories, and backstories.

For Mitchell Brant, it’s a sensation of coming up short, a belief that he doesn’t quite measure up as is, inspiring him to lie and tell tall tales about himself. For Ryan Swinton, it’s the possibility that someone won’t laugh at one of his jokes, or that he might inconvenience or upset a friend. For Joe Marma, it’s that he will be judged as lacking, second-rate, always finishing behind his older brother in everything he does. And for Marc Kuslanski, it’s the frustration of uncertainty, the specter of problems and puzzles he cannot solve, of mysteries he cannot fathom.

Rejection. Disappointment. Failure. Misunderstanding. Heartache. Loss.

We are all afraid of something. We all must wrestle with our own personal ghosts and ghouls, worries and fears.

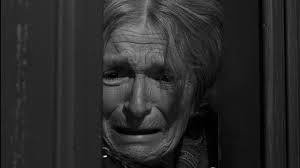

For Wanda Dunn, an old woman we meet in a third-season Twilight Zone episode titled “Nothing in the Dark,” the albatross that weighs her down is made clear from the start.

Wanda Dunn is terrified of death.

The story opens with Wanda holed up in her broken-down tenement, snow falling outside her windows. She spies someone on the step just beyond her door–a young man in uniform. She cowers in a corner, fearful of being seen. And then a whistle blows, a gunshot rings out, and the man falls.

Reluctantly, Wanda opens her door, just enough to peek outside. The man (played by a twentysomething Robert Redford) is lying in the snow.

He pleads to her, says he’s a police officer and that he’s been shot and needs help.

“You’re lying,” the old woman says. “Why can’t you leave me alone? I know who you are. I know what you are.”

It is here that Rod Serling provides the opening narration of the episode. In the voice-over, he tells us that Wanda Dunn thinks the man outside is, in actuality, Mr. Death in disguise.

But the police officer continues his appeal. “Unless you help me,” he says, “I’m going to die. I don’t think I can move.” He tells her his name is Harold Beldon and asks her to call a hospital.

She tells him she has no telephone, and cannot call anyone.

When he asks if he can come inside, out of the cold, she balks. “I’d have to unlock the door,” she says. “I can’t do that. I don’t want to die. I know who you are.”

He grimaces, clearly in pain, and tells her as much.

Eventually, and grudgingly, she opens the door and lets Officer Harold Beldon into her home . . .

Later, we see her tending to him, as he lies in a bed. She brews him some tea, not as afraid of him now, apparently comforted by the belief that he is who he says he is–just a police officer injured in the line of duty, and not the angel of death come to snatch her away.

As they talk, we learn that Wanda Dunn lives alone. There are no neighbors. They’ve all moved away. And she can’t open the door, seek out a telephone to call a doctor, even if there still were a neighbor.

“I can’t let him in,” she says.

“Mr. Death . . .” Officer Harold Beldon replies, catching on.

“I know he’s out there,” Wanda says. “He’s trying to get in. He comes to the door and knocks. He begs me to let him in. Last week he said he came from the gas company. Oh, he’s clever. After that, he claimed to be a contractor hired by the city.” He’d told her the building had been condemned and she had to leave. But “I kept the door locked, and he went away.”

The officer objects, pointing out that people all over the world die every day. How can one man, a single Mr. Death, be in all those places at once?

She says she doesn’t know, but she has seen him before. Every time someone she knew died, he was there. She admits, others don’t seem to see him, but she thinks she does because she’s old, and because her “time is coming.”

“I could see clearer than younger people could,” she says. And yet–his face is always different. She can never be sure it’s him at first glance, and that’s why she hides, shuts herself in, not allowing herself to venture outside.

“How can you live like this?” Officer Beldon asks.

To which she responds, “But if I don’t live like this, I won’t live at all. If I let down, even for a moment, he’ll get in.”

Suddenly there’s a knock. She doesn’t want to answer, but the officer urges her to. She opens the door a crack. A burly workman is there.

“I’m sorry, lady,” he says, “but I’ve got my orders. I can’t fool around any longer.”

The man forces his way in, and Wanda Dunn is certain it’s Mr. Death.

The man assures her he’s just a worker arriving to warn her that she needs to move out immediately. His crew is set to begin demolishing the tenement in one hour’s time.

“I’m surprised anyone still lives here,” he says. Hasn’t she read the notices, opened her mail? It’s an old building, he explains, dangerous. It’s got to come down.

“That’s life, lady,” he goes on. “People get the idea I’m some sort of destroyer . . . I just clear the ground so other people can build . . . It’s just the way things are . . . Old animals die, and young ones take their places. Even people step aside when it’s time.”

“I won’t,” she says, and implores Officer Beldon to help, explain to the man that she can’t leave. But the man asks who she’s talking to. There isn’t anyone else in the room but the two of them.

Pressed for time, ready to coordinate the demolition, the workman leaves, again issuing a warning that she needs to leave the building immediately.

But Wanda Dunn is no longer concerned about the workman or the tenement.

“He didn’t see you,” she says to the officer when they are once again alone. Officer Beldon tells her to look in the mirror. When she does, she can only see herself. The police officer has no reflection.

Finally realizing what has happened, Wanda exclaims, “You tricked me! It was you all the time! But why? You could’ve taken me anytime. You were nice. You made me trust you.”

He gets out of bed, asks, “Am I really so bad?” And tells her she’s not afraid of him, of death, but of the unknown. “Don’t be afraid,” he says. “The running’s over. It’s time to rest.”

He offers her his hand.

“I don’t want to die,” she says.

But he encourages her, softly, gently, and they touch.

“You see?” Mr. Death says with a smile. “No shock. No engulfment. No tearing asunder. What you feared would come like an explosion . . . is like a whisper. What you thought was the end . . . is the beginning.”

“When will it happen?” she wants to know. “When will we go?”

But they already have. He tells her to look at the bed. She sees herself lying there, lifeless.

Understanding at last, fearing no longer, she smiles, and, arm in arm, they walk out the door.

In the closing narration, Rod Serling sums it up like this:

“There was an old woman who lived in a room and, like all of us, was frightened of the dark, but who discovered in a minute last fragment of her life, that there was nothing in the dark that wasn’t there when the lights were on.”

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

July 23, 2015

The Value of the Junk Pile (Or, Discovering the Right Service Stance)

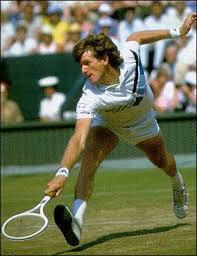

I was riveted, glued to the television set, watching a sport I had never paid any attention to, and realizing, even though I was just a kid, that sports history was being made.

To put it mildly, it was a surprise I was watching the 1985 Wimbledon Men’s Singles Final. Though I was a big sports fan, at the time my tastes were limited to football, baseball, basketball, and a little bit of ice hockey sprinkled in. Tennis? I didn’t know a break point from a deuce point; a baseline from a service line. But when my older brother John came into the family room on that hot July morning, he turned on “Breakfast at Wimbledon.”

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“I heard this guy has a huge serve,” he said. “I wanna watch it.” This was a surprise, too. John had recently graduated from high school, and I’d always looked up to him. Nearly a decade my senior, he was patient with me and rarely told me to get lost when I’d hang around with him and his friends. He’d been a star athlete in school, but, like me, had never really been a fan of the game of tennis.

Even so, he followed the world of sports enough to know that a significant story was being written on the lawns of the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club. Kevin Curren, a veteran of the professional tennis circuit, was making major waves, beating John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors in succession to reach his first Grand Slam final. Curren wasn’t regarded as a top player–but he had one of the game’s strongest serves. This my brother wanted to see.

Curren’s opponent that day was a seventeen-year-old prodigy named Boris Becker. Few people knew who he was at that time, apart from tennis aficionados. I certainly had never heard of him. But that was about to change. He shocked the tennis world, instantly becoming a worldwide star, by defeating Curren to become the youngest Wimbledon champion in history.

I was struck by Becker immediately. With his daring, net-rushing, athletic style, his charisma and hustle, he was a joy to watch. And, as it turned out, it was Becker, not Curren, who had the truly dominating serve.

I was hooked. I loved the one-on-one aspect of the sport, the geometry of the court, the strategy and tactics, the way the crowd would grow whisper-quiet between points and then erupt when a brilliant stroke was made.

The very next day, I went to the local public courts, borrowed one of my parents’ old wooden rackets (!), and worked on my serve. I hadn’t ever served a tennis ball before, so it took some getting used to. But, first and foremost, I adjusted my service stance to mimic Boris Becker’s. It was natural enough–he was a right-hander, and so was I, after all. So, I opened up my stance, just as Boris did, facing the corner of the court where I aimed to hit the ball.

Try as I might, it just didn’t feel right. I attributed it to my being a beginner. But as the days moved forward, as summer break rushed toward the inevitable and unwelcome start of another school year, I realized I wasn’t making much progress. My serve was still not working.

That’s when I understood. It wasn’t my serve I was practicing. It was Boris Becker’s. The stance that worked so well for him felt awkward and uncomfortable for me. It just took me some time to figure it out.

So I changed my stance, closing it up, with my front foot now to the right of my back one. I felt the difference right away. This position felt easy, natural, and fluid. My serve improved literally overnight. And to this day, I still serve with a closed stance.

At first, I bemoaned the fact that it took me so long to make the switch. Couldn’t I have become a better player, a better server, if I had just started in a closed stance to begin with? But then I saw the truth. I had to go through the awkwardness in order to pave the way for the finished product.

By learning what didn’t work for me, it made it easier and clearer to see what did.

**********************

Have you ever written a scene, or even an entire chapter, only to discover, after the fact, that it’s all wrong? It doesn’t need a little tweaking, or a few minor edits. It is just . . . wrong. Awful. A complete and unequivocal flop.

I’ve certainly written such chapters. In The Eye-Dancers, for example, I remember vividly the quagmire that was chapter eighteen. It was one of the longer chapters in the novel, and, after writing the first draft of it–all twenty or so pages–I reread it, and said, “What was I thinking? Seriously? This is horrible!” I was shocked that I hadn’t noticed this earlier, when I was in the process of writing the chapter. Admittedly, during the writing of the chapter, I was aware that the words were not flowing, the dialogue not coming smoothly. But I had no idea just how bad it was until I went back and read the entire thing.

My first reaction was predictable. I bemoaned the fact that I had just wasted so much time writing such drivel. I took a breath, shut off the PC, and resolved to keep away from the manuscript for at least a day. I needed a break.

When I returned to it two days later, I reread the chapter, this time with more patient and much fresher eyes. While I still thought the output was atrocious, I was able to focus more clearly and spot where it was I’d gone wrong. The germ of the idea was fine. It was the execution that was lacking. The chapter needed more energy, more gusto, more forward momentum. By rereading the first draft, the second draft came clear. The fog lifted, and I felt invigorated.

I rewrote the entire chapter, and this time the words came more easily, the dialogue popped, and the POV character (a tip of the cap to you, Marc Kuslanski!) came into sharper focus. When I read through it upon completion, I knew it was right–not perfect maybe–no chapter ever is. But right. I scrolled to the bottom of the screen, inserted a page break, and keyed the words, “Chapter Nineteen,” into the yawning mouth of the white space. I was ready to press on.

No doubt, it had been a frustrating and time-consuming experience, but I was thankful for the first draft of chapter eighteen. It was a necessary part of the process, a sharpening of the pen, so to speak, a way to clear the creative cobwebs and allow the real story, the true story, to come through.

I have no doubt I’ll have more “chapter-eighteen experiences” in the future. I’ve had a few already while writing the sequel to The Eye-Dancers. And, while I may never fully embrace these authorial detours, these mazes through the junk pile to sift out the trash and unearth the jewels, I will always appreciate and acknowledge, however grudgingly, their value.

Because, when it comes right down to it, sometimes you just have to serve a few double faults with the wrong stance before you can hit those perfectly struck aces with the right one.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

July 2, 2015

Author Interview with Jessica Wren

When I began blogging three summers ago, little did I realize how much fun and rewarding it would be. I was, to put it bluntly, clueless when it came to the blogosphere. So many aspects of blogging are great, but if I had to choose the best of the best, that would be easy–the many virtual friendships I have formed with so many talented and wonderful people throughout the WordPress community. I am continually humbled by all the support and goodwill that permeates this very special network.

One of those talented and wonderful wordsmiths is Jessica Wren. Jessica took the time recently to interview me on her great website, and now I am returning the favor, chatting with Jessica about the art of writing and about her engrossing novella, Ice, which I very much enjoyed.

It’s my pleasure introducing Jessica Wren. I hope you enjoy the interview!

*******************

1. Have you always known that you wanted to be a writer? When did you first discover that writing was something you had a passion for?

I have been writing for as long as I can remember. When I was twelve, I wrote a novelette. My seventh-grade English teacher did a serious review, writing on a piece of paper the good and the bad (this was, of course, before the Internet). The fact that someone took me seriously at that time spurred my confidence as a writer. I still have that review; it is one of my most treasured possessions.

2. What, or who, are some of your inspirations as a writer? Do you have any favorite authors? Novels?

Stephen King. I think I have read just about every work written by him, and Ice has been compared to some of his works (most notably, The Shining). I have also drawn inspiration from some of the Latino writers, mainly Isabel Allende and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. In fact, Ice was loosely based on One Hundred Years of Solitude. I created Minterville as an American Macondo.

3. If you could offer an aspiring writer any single piece of advice, what would it be?

Don’t listen to negative people. Pay attention to constructive criticism, of course, but if someone is actively trying to work against you, get as far away from him/her as possible.

4. In your novel, Ice, it struck me right away that there is virtually no cell phone presence in the town of Minterville. Of course this is mostly due to the telepathic Minter ability of the residents (more on that in a moment), but I couldn’t help but wonder if, in presenting the town in this way, that you might be making a statement about the smartphone culture we live in? Do you feel that society has gone too far in its dependence on smartphones and digital technology in general?

I never thought about it, but now that you mention it, maybe I was, subconsciously, trying to make a statement about the importance of community and ties, and how technology addiction can be damaging to one’s social skills. Cell phone reception is poor in Minterville because of their location deep in the woods, but the residents there are used to it and have come to rely on the Minter and person-to-person communication.

5.Speaking of the Minter, and the ability of the town residents to communicate on a telepathic level, I was struck by your portrayal of small-town America. Are you from a small town originally? Do you live in a small town today?

Today, I live in Brunswick, Georgia, which has grown a little too much for my taste. Minterville is modeled after Argyle, Texas (where I did live as a child). In Argyle (at least at that time), everyone knew everyone, there were many community events, and while we couldn’t communicate telepathically, we all knew each other’s phone numbers. It was also virtually crime-free.

6. Ice is written in several Parts, each Part narrated, in a first-person format, by a different resident of the town. That’s a very interesting literary technique, and one that presents the reader with different perspectives over the course of the novel. What inspired you to write the story in this manner, as opposed to a third-person narrative throughout or from the first-person point of view of just one character?

I chose to tell Parts 1 and 5 from Elliot’s point of view because he’s a mainly objective character. He was actually originally going to be my only narrator. However, my editor (who’s also my husband) pointed out that by doing that, I would miss out on the emotional depth that characters directly involved in the events, such as Andy (on the outside) and Carolyn (on the inside), could provide. I finally decided to keep Elliot as the narrator for the beginning and the end (before and after the main crisis) because of his objectivity and because as far as that particular town is concerned, he functions as an “everyman.” To be honest, I wish I had used the third-person.

7. One of the characters in Ice refers to the press as a “group of blood-sucking vultures.” Does this harsh critique of the press mirror your own views at all?

I do believe the media does “spin” stories to generate ratings, but my view is not nearly as harsh as Elliot’s. He is upset because he feels the media presence in Minterville is disruptive and that they are taking advantage of their tragedy to boost their own ratings (and once again, he is pretty much speaking for everyone).

8. There really isn’t a single main character in Ice. In effect, the entire town of Minterville is the main character. This brought to mind certain other works, such as Winesburg, Ohio, by Sherwood Anderson, a short story collection where the stories are not chapters in a single novel, but rather separate, individual stories that are connected through theme, characters, and location. Was it an intentional choice you made before writing the novel not to have one main character? Or did that evolve over the course of writing Ice?

It evolved over the course of the writing. It took me a lot of time and frustration to decide the best way to present this particular story. At one point, I was even planning to do it vignette-style (similar to Winesburg, Ohio). Out of everyone who reviewed Ice, I think you are the only person that got that Minterville itself was the main character. I made it a deliberate point of saying that the populace tends to be of one mind. One thing I deliberately avoided doing was presenting anything from Tom’s perspective, even though he is directly at the center of the action. As a “naturalized” resident, so to speak, he simply does not have the ability to think about things the same way everyone else does.

9. In a similar vein, did anything really surprise you as you wrote the novel? Did some things go in a completely different direction than you had at first envisioned?

Absolutely. For starters, the twist at the end involving Cierra was something I added in a week before publishing. I had to tone down a lot of the characters who were becoming too mean. Stephanie was originally a bully who verbally abused Elliot their whole lives, and Barbara was a lot nastier in the beginning. In one deleted scene, she told several of the other women involved that they deserved to die (for various reasons). Ice was a short story that I started writing for a contest that just kind of grew.

10. Ice is an emotional roller-coaster ride, with a lot of ups and downs as the characters navigate a terrifying situation. In the end, when it’s all said and done, what do you hope the readers of Ice will take away from the novel?

The main lesson is always trust your instincts. When your gut is telling you that something (or someone) is “off” it probably is. The other main things I am hoping readers will take away are compassion and empathy, and taking responsibility for one’s actions. The people of Minterville don’t for a single second blame the person whose long-ago misdeeds caused the whole incident, because when it was all said and done, he had done everything in his power (which included a plan to permanently get rid of the criminals at the expense of his own life) to avert the tragedy, and when he couldn’t, he alone accepted the consequences. I hope readers will notice that he never once blamed Manuela or anyone else for his decisions.

11. Will there be a sequel? What are you working on now?

I’m planning a whole Minterville series. Although it was the first published, Ice is going to be Book 7. Book 8, which I will write when I’m done with my current project (about that in a minute), will be called Chill and it will be a sequel in which Manuela gets a taste of her own medicine. Book 1 will be Blizzard (James Minter’s story), Book 2 is Freeze (Manuela’s story), Book 3 is Snow Storm (Tom Watson’s story), Book 4 is Shiver (Sebastian’s story), Book 5 is Frost (Barbara Jenkins’ story), Book 6 is Winter Winds (more about the events of 1993).

What I’m working on now is a four-part series called the Cadiz Beach Series. The titles will be Earth, Fire, Water, and Wind, which revolve around a criminal defense attorney named Vincent McPherson who tries to rid Cadiz Beach, Florida (another fictitious town), of the Irish Mob. I’m doing the rough draft for Earth now. Vinny (as he is called) defends two young people accused of killing the son of a notorious Irish mobster. This trial unleashes all the fury of the Mob on this small, beachfront community . . .

**************

Jessica Wren is a writer who has published exactly one ebook. She has created this page to share her infinite wisdom with professionals such as herself. A high school teacher in a small Georgia city, she knows everything about being a cop, a lawyer, a drug dealer, a serial killer, a teenage boy, and every other known identity. She gives top-notch professional advice about writing by which she consistently fails to abide. Her other talents include boring teenagers to death, aggravating her husband, driving extra-slow when others are behind her, and dropping food on her blouse. Jessica’s ultimate dream is to retire to a one-room shack with 20 cats, where she will sit on the porch and shout “Get out of my yard!” while swinging a broom at anyone who happens to pass by.

You can connect with Jessica on her website, her Twitter page, and on Goodreads.

Thank you, Jessica, for a great interview, and thanks so much to everyone for reading!

–Mike

June 19, 2015

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Or, The Dirt Hole at the Side of the Yard)

The summer when I was eight years old, I fell in love with digging. Not just any digging. Not some small pea-hole in the corner of the yard. No. I went all-in. I recruited my friend Matt, and together, we planned on digging our way straight through to the center of the earth.

Of course, the question had come up–where could we even undertake our mission? My mother wouldn’t go for us digging up her flower garden or vegetable garden. She wouldn’t want us to tear up the front yard, either. That didn’t leave us with many options. We asked if we could use the side yard.

The side yard consisted of a narrow alley that separated our house from our neighbor’s. Abutting our house was a red-brick patio that led to the back gate, but beyond that was a small strip of grassy real estate just begging to be ripped into. The thing was, that small strip wasn’t technically on our property. It belonged to our next-door neighbor, George.

George had lived in that house since it was built, decades ago. He lived there with his wife, daughter, son-in-law, and two grandsons (who, incidentally, inspired two of the characters in The Eye-Dancers!) At the time, he was a tall, jovial man in his sixties who, every Christmas, dressed up as Santa Claus. As far as I was concerned, there was no chance he’d tell us we couldn’t dig a dirt hole in the side yard.

And he didn’t. He said, “Go ahead!”

My father handed Matt and me a pair of shovels and told us not to overdo it. “Just take it easy,” he said.

By lunchtime, we’d already tunneled down several feet. When my mother came out to check on our progress, I was standing in the hole, nearly up to my chest. Matt was up top, examining a large rock we’d unearthed.

“I don’t think George thought you’d be digging a hole that deep,” she said, her eyes wide. I swelled with pride. All this in just a few hours . . .

We ate heartily, our appetites stoked, and then resumed with our work. We widened the hole, making sure we had plenty of elbow room, and created small earthen “steps” on one of the sides, ensuring that we’d be able to climb out once we dug in over our heads. By three o’clock that afternoon, we were both drenched in sweat. But we didn’t stop, didn’t slow down.

“We’re almost in all the way,” Matt said when the top of the hole was at eye level. “How far do you think we can go?”

“All the way,” I said. In my mind, we had only just begun. We had an entire summer before us, yawning like a chasm full of wonders. “And who knows what we’ll find down here. Maybe we’ll even see Merwks.” Merwks (not a typo–the “w” was very important!) were creatures who inhabited the depths of the earth. They were small, brown, furry monstrosities with no eyes and fangs sharp enough to sever stones. I had first imagined them two years earlier, and was convinced they existed. When I told Matt about them, he was sold.

“We better be careful,” he said. “Merwks have sharp teeth!”

We brought our shovels down again, and again, and again, striking earth, eager to discover ancient secrets, buried treasures, perhaps even a skeleton or two. We were tired, bone-tired, but our effort did not flag, our eagerness did not waver. There was a new universe that awaited, monsters in the dark we needed to reveal. Looking back now, I can still remember, clearly, vividly, the elation I felt that day. I was young and free, embarking on an adventure for the ages.

But then my mother came outside and put an end to it.

“That’s enough for today, boys,” she said. “Time’s up.”

We whined a little, but we were tired enough not to carry on with it too long. There was tomorrow, after all.

Or was there? My mother warned me that when George came home that night, he might not like seeing his side yard with a four-foot-deep hole smack dab in the middle of it.

“But he already said we could dig,” I protested.

“I’m not sure he realized how . . . committed . . . you were,” she said.

When George got back, we all joined him at the side of the yard. He smiled at me when I looked up at him.

My mother apologized for the size of the hole, told him she hadn’t expected it to be such a crater. But George held up a hand.

“They’re only kids once,” he said. “Let ’em dig.”

And so we did. Matt and I were at it the next day. We had Merwks to find.

*******************

Anytime I begin a new writing project, I need to feel excited. I might have a workable idea, a complex plot, an intriguing protagonist, but if I don’t feel completely fired up, I know, before I even start, that the story will go nowhere. Over the years, I have tried to force it, attempted to manufacture enthusiasm that wasn’t there organically. It never works. At least not for me.

When I wrote The Eye-Dancers, I truly believed it was a one-shot deal. Sure, I’d write other stories, other novels. I wasn’t retiring as a writer. But I didn’t plan or intend for there to be a sequel. Then, about a year and a half ago, I had–for lack of a better term–a vision.

I was lying in bed in the middle of the night–something had jarred me awake. A dream? A nightmare? Something my subconscious had been wrestling with, interacting with? I suppose I’ll never know. All I know is that, when I woke up, I visualized something with crystal clarity. I saw a huge building, larger than a dozen football fields, its walls and columns climbing high into a nighttime sky. I saw the four main characters of The Eye-Dancers—Mitchell Brant, Joe Marma, Ryan Swinton, and Marc Kuslanski–standing before the structure, gazing up at the sky. They weren’t looking at the moon or the stars or a meteor that had entered Earth’s atmosphere, afire, burning up as it sped toward the surface.

They were staring, transfixed, at a pair of blue eyes that stretched across the entire canvas of the night sky. The eyes glared at them, swirling, the blue in them darkening like a bruise. And I knew. I had a surge of momentum rush through me like a lava flow. I didn’t have a plot. I didn’t have a direction. But I had an inspiration, a need, to tell a story. There was no silencing it. It was time to write a sequel.

And as I sit here, eighteen months later, nearing the end of the middle portion of the novel, as the stretch run comes into view, just around the next bend, I still feel that enthusiasm, that desire, that need to make it all the way, to tell the story to the best of my ability straight through to the end.

That, I believe, is the key to it all. Whether you’re writing a novel or painting a picture, crafting a memoir or singing a song, you have to feel that same sense of wonder and excitement you once did, when you were eight years old. Sometimes, I think, writing novels is nothing more than my way of remaining a kid, discovering new adventures to explore, new avenues to traverse, new enthusiasms to pursue.

“May you live with hysteria,” Ray Bradbury once wrote, “and out of it make fine stories. . . . may you be in love every day for the next 20,000 days. And out of that love, remake a world.”

*********************

Matt and I continued to dig throughout that summer. Granted, our efforts waned as the calendar ticked on, as the start of the school year and third grade approached. But we kept at it, telling each other scary stories the deeper we went, wondering if our next shovelfull of dirt would finally unearth a sightless, sharp-fanged monster.

It never did. Try as we might, we never came face-to-face with a Merwk.

*********************

My parents still live in the old house, and, invariably, when I visit, I wander over to the side of the yard and walk along that narrow strip of grass. The dirt hole has long since been filled in, of course. But I always look, and remember.

The thing is, even to this day, I still believe in Merwks.

If you want to discover them, you just have to dig a little deeper.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

June 6, 2015

A Step-by-Step Journey–Or, Words of Wisdom from a Fictional Minor-League Catcher

In the 1988 romantic comedy Bull Durham, there is one sequence when veteran minor-league catcher Crash Davis pulls aside the young pitching phenom Nuke LaLoosh to offer words of advice. Davis knows talent when he sees it, and he knows that LaLoosh is headed, ultimately, for the Major Leagues. Though raw, and with much to learn, the young pitcher has a golden arm, blessed with a rocket-like fastball and an off-the-table curve. He has future superstar written all over him.

But he’s arrogant, hot-tempered, immature, and, Davis is sure, not at all prepared to handle the fishbowl lifestyle of the Major Leagues. And so on a road trip, as their minor-league team, the Durham Bulls, gears up for a new opponent, Davis instructs LaLoosh on the fine art of the interview.

“You’re gonna have to learn your cliches,” he says. “You’re gonna have to study them. You’re gonna have to know them. They’re your friends. Write this down: ‘We gotta play it one day at a time.'”

As LaLoosh does indeed write this down, he says, “‘Got to play’ . . . it’s pretty boring.”

Davis is quick to respond: “‘Course it’s boring, that’s the point. Write it down.”

He provides two other canned responses to interview questions, as well, both as cliched and dull as the first. Indeed–how many times have we heard this oft-repeated phrase: “One day at a time; one game at a time . . .”

“So, are you looking forward to playing the Yankees next month?”

“Next month? Next month? This is this month! We’re not even thinking of the Yankees. Who are they? We gotta take this one game at a time. If we start looking ahead to next month, the series against the Yankees won’t even matter because we’ll have lost the next few anyway.”

It’s frustrating for the interviewer and the audience alike. We listen to this, and think, “Can’t they ever be honest? Of course they look ahead. They have to. Anybody would.”

But maybe, just maybe, it’s not always just a tired cliche. Maybe sometimes, they’re actually telling the truth.

**********************

Have you ever been there? You’re writing a novel, or a memoir, or any long work of literature, and you know that just down the road, perhaps as near as the next chapter, a major development beckons. The protagonist will face a monumental challenge, a huge shift in the plot will occur, perhaps someone instrumental to the story will die. Regardless of the specifics, it is a crucial development, one of the most important sequences of the entire work.

But it’s not the chapter you’re working on . . .

Speaking of, the chapter you are working on is relatively minor. There are no groundbreaking events, no epiphanies or “aha” moments, no twists and turns that will create a sea change for the rest of the story. It’s a quiet chapter, understated, a small hors d’oeuvre before the meal is served, an undercard to kick off an evening where everyone in the audience is breathlessly awaiting the main event.

When I wrote The Eye-Dancers, there were certainly moments just like this. There is a short chapter where Ryan Swinton walks off from the group, needing some space to think and reflect. Later on, toward the climax of the novel, Marc Kuslanski has a similar conversation with himself, exploring the troubling reality of paradoxes, that not everything can be rationally and neatly explained.

It’s precisely at such times as these that Crash Davis’s advice to his young teammate most applies. Because–if we rush through the little scenes, the reflective and subdued chapters, if we slap them together without much effort out of sheer impatience to move forward, it won’t even matter what that earth-shattering revelation will be in chapter 29, or how our protagonist will manage to survive the dangers at book’s end. Regardless of how mesmerizing the big scenes are, they are built, in large part, by the “small” chapters and interludes that precede them.

I have found that, when writing a novel, the task sometimes seems so large, so daunting–often literally taking years to complete–that it’s dangerous thinking too far ahead. Granted, there needs to be some sense of direction. I know, for me, I like to have an idea where I’m going before I begin the first chapter, and at times, during the course of writing the story, if an idea strikes me for a scene several chapters off, I’ll jot it down to make sure I don’t forget it.

But if I start worrying too much about scenes as yet unwritten, developments around the bend, as it were, if I spend too much time stressing about specifics five or ten chapters hence, then I am in real trouble. Suddenly the scenes I am working on become harder to write, and I find it more difficult to concentrate on the task at hand. I may even get bogged down with doubts, wondering if the novel as a whole will be worthwhile or just some disastrous literary flop.

Indeed, if I am about to begin chapter 17, as I am in the sequel to The Eye-Dancers, even as I write this post, I need to focus exclusively on chapter 17. Not chapter 18, or chapter 19, or chapter 26. Even more specific than that, I need to focus on the next word, the next sentence, the next paragraph. For, when it’s all said and done (a fitting description in a post talking about an old cliche!), a story is indeed built one word at a time, one chapter at a time.

The Yankees next month? They can wait.

Just ask Crash Davis.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

May 22, 2015

A Versatile Blogger Award, Breaking More Rules . . . and a Thank-You

It seems hard to believe that I’ve been blogging for close to three years now. I remember vividly making the decision, in the summer of 2012, to create a blog devoted to my then-upcoming novel, The Eye-Dancers. With those first tentative steps, little did I realize how joining the WordPress community would add to my life and enable me to make many friends from around the world.

And that still impresses me, amazes me, even. You have to remember that I am old-school, having grown up in the ’80s and gone to college in the ’90s . . . my generation was the last one to come of age in a world sans email and chat rooms and social media and smartphones. So it still astounds me that we have such reach today, such an ability, such a platform–literally, a worldwide audience. Children growing up today likely take this digitalization of our world for granted. To them a smartphone is no more extraordinary than the mail would have been to me in 1989.

So for this lifelong reader, writer, classic movie lover, comic book aficionado, and Twilight Zone enthusiast, the WordPress community has been a tremendous blessing–right from day one. And it’s with great appreciation and gratitude that I accept the nomination of the Versatile Blogger Award from Melissa at Today, You Will Write. For those of you not familiar with Melissa’s fabulous blog, please take a virtual trip over there. You will be glad you did!

I actually was nominated for the Versatile Blogger award some twenty-six months ago, but I wanted to accept again so I could thank Melissa for nominating me and also thank everyone for all your support (more on this at the end of this post!). Additionally, the rules for this award have changed a little since March of 2013, and I wanted to take a stab at it. (Not that I follow rules when it comes to blogging awards!)

Speaking of, here are the rules for the Versatile Blogger Award:

Thank the person who gave you this award.

Include a link to their blog.

Next, select 15 blogs/bloggers that you’ve recently discovered or follow regularly.

Nominate those 15 bloggers for the Versatile Blogger Award with links to their blogs.

Finally, post 7 things about yourself. (Answer the questions from the person who nominates you, and then ask 7 of your own.)

Also remember to add the Versatile Blogger image to your post.

Here are the seven questions Melissa asked, and which I now will answer . . .

1. Who is your favourite author or what is your favourite book?

It’s very tough to choose just one! As for authors, I can’t really say I have a favorite–there are so many! Two, however, who have always served as inspirations are Ray Bradbury for his enthusiasm, imagination, and heart; and Truman Capote for his skill and talent–a master wordsmith if there ever was one.

A favorite book? Very difficult to choose just one. But if I absolutely had to, I would probably say To Kill a Mockingbird.

2. If you had a super power what would it be?

I’m not sure it’s a super power, but I would probably choose a photographic memory. I’ve always been keenly aware of all the things I forget. It strikes me that, if you think about your life, probably 99% of it is forgotten. Granted, much of it is trivial–what did you have for supper on June 17, 1999? What time did you go to bed on February 7, 2006? Even so, it seems sad that we forget so much.

3. If you could produce a movie, which one would you choose?

The Eye-Dancers of course!

4. How has WordPress helped you to become a better writer?

This is a great question, and I think the answer is–the regular (or, for me these days, semi-regular!) posting of articles. Maintaining a blog forces you to come up with (hopefully) original, creative posts on a fixed schedule. You can’t just wait until you feel inspired or when the spirit moves you. If you want to maintain something of a steady schedule, you have to write posts on a regular basis. This steady need to come up with original material has been a wonderful way for me to exercise my creative writing muscles. They are no longer permitted, since I’ve joined WordPress, to get flabby or out of shape!

5. What fun thing do you do to keep yourself from burning out?

Nothing cheers me up like watching reruns of, well, Cheers or The Honeymooners, or reading a corny old comic book. And when a physical release is needed, I have always felt at home on the tennis court.

6. When you were a child, what did you want to become?

For a very brief period, I toyed with the idea of becoming a marine biologist, and there was a time I wanted to be a detective, but for the most part, I have always wanted to be a writer.

7. If you could live anywhere in the world where would you go?

Right where I am–living in the hills of Vermont! A close second would be Prince Edward Island, Canada, the most beautiful place I’ve ever experienced.

Now it’s my turn to ask seven questions for anyone who wants to accept this award. Yes, it’s rule-breaking time! Rather than nominate fifteen bloggers, I want to nominate everyone who follows The Eye-Dancers website! I hope very much that some of you will accept this nomination and delve into the following questions . . .

1. You have the opportunity to step into a time machine and choose any destination you want: past or future. When and where would you go?

2. When you were growing up, did you have an idol? If so, who was it?

3. You have three choices, and only three: you can watch either a 007 movie, an Alfred Hitchcock classic, or a reality TV show. Which one do you watch?

4. What do you enjoy most about blogging?

5. What is something about you (it could be a hobby, interest, talent–anything) that most of your friends would be surprised to learn?

6. If money were not an object and you could do anything you wanted for a career or profession, what would you do?

7. There are three items on the table in front of you (only three!): a chocolate bar, a Stephen King paperback, and a Rubik’s Cube. Which of these do you reach for?

To conclude, I wanted to thank everyone who has visited, supported, and read The Eye-Dancers blog. Without your interest and participation these past three years, this blog would not exist today. Admittedly, I am not posting as often as I once did, as I continue to work on the sequel to The Eye-Dancers (which now, at long last, is close to having an official title!), but my appreciation for all of you is as strong as ever. You are the reason I enjoy blogging as much as I do. Hopefully the best is yet to come.

Thank you so much for reading these scribblings of mine all these many months!

–Mike

May 7, 2015

When the Lilacs Bloom

Spring, in my neck of the woods, is easily the most longed-for season of the year.

All too often, however, spring is like a bashful pixie, a reluctant, shy, embarrassed late-arrival to the all-season party where winter dominates the proceedings and monopolizes the conversation. Eventually, though, as the pages of the calendar flip forward, day by day, we reach the month of May, when spring finally unfurls its plumage, the self-consciousness gone, the reticence of March and April a forgotten thing.

Almost overnight, it seems, grasses that were yellow and brown turn a rich, verdant green.�� Buds appear, as if by magic, on the trees.�� Colorful grosbeaks and bobolinks return to the area, and the year-round songbirds sing louder and longer, as if basking in the long-awaited, nearly forgotten warmth.

And. perhaps most spectacular of all, May is when the lilacs bloom . . .

This weekend, I will take the seven-hour drive from Vermont, my adopted state for the past eleven years, “back home” to Rochester, New York.�� I’ll visit my parents, my brothers and sister, extended family, and old friends.�� I look forward to it.�� It is always nice visiting my roots, inspirations, the people and places who have been there for me from the beginning.

And, time permitting, I will also make a point to see the lilacs.

Rochester has long been nicknamed the Flower City, and no time of the year embodies this more than the month of May, and no single piece of real estate more so than Highland Park.

Situated on the city’s south side, Highland Park is home to the largest collection of lilac bushes in the United States, boasting more than 500 varieties of lilacs and 1,200 plants in all, bedecked on a green hillside that spans 22 acres.�� Every May, for a span of ten days, the park hosts the Lilac Festival. It’s an enormous event, bringing in more than 500,000 visitors from around the world.

For me, though, I most enjoy the park early in the morning, before the food and craft stands open, before the crowds gather–when there is still dew on the grass and when you can listen, without interruption, to your thoughts and luxuriate in the heady fragrance of the lilacs.

I savor it, savor them, drinking them in because I know they will be gone within a fortnight, the delicate petals fallen, the purples and pinks and lavenders stripped away, the color show over and done until the same time next year.�� It always seems sad that such a magnificent display should be so brief, such a bounty so fleeting.

Perhaps it is.�� But it also serves as a reminder.

************

Have you ever been struck by an idea, something so inspired, so riveting, so full of life and vitality that you instantly knew you had to let it out?�� Maybe it was a concept for a short story, or a new focus for a novel.�� Maybe it was a poem, gift-wrapped, arriving in total, the lines and rhythms dancing before your eyes like gemstones.�� Maybe it was a landscape or a street scene for you to paint, the contours, shadows, and nuances perfectly clear in your mind’s eye.�� Maybe it was a tactic, an approach, a way to sway your audience or win the approval of your coworkers on a long-debated and polarizing project.

Moments like these are energizing, and often hit us without warning, a creative bolt from the blue, as it were.�� They are as invigorating as they are rare.

Sure, ideas strike every day.�� But how many of them make you stop what you’re doing mid-thought, or distract to the point where you forget the supper in the oven or fail to see that red light switch over to green (the motorist behind you will certainly let you know should this happen–and yes, I speak from experience!)?�� I know for me, such ideas only occur infrequently, and there is no way of guessing when they will come.

I’ve tried to figure it all out.�� Is there something specific I tend to do that might encourage the best ideas to strike?�� Is there a certain TV show or movie I should watch?�� Maybe a book I should read?�� Or maybe a particular food . . . perhaps a “creativity diet” that exists, a certain combination of vegetables, starches, and nuts that assures at least one winning idea per day?

But if there’s a secret magic formula, I’ve yet to discover it.�� The muse strikes when it will, a capricious, fickle thing, as inscrutable as the undiscovered wonders at the bottom of the sea or the farthest reaches of space.

The truth is, those earth-shattering ideas that rock my creative world and send paradigm shifts running through every page of a manuscript are as rare and transitory as the lilacs that grace Highland Park for a fortnight every spring.�� And maybe that’s as it should be–for all of us.�� If they struck every day, they would no longer be special, no longer demand our attention and make us take notice.�� They’d become ordinary, just another check mark on the to-do lists of our lives.�� “Brush teeth, check.�� Make breakfast, check.�� Pick up groceries, check.�� Pay the bills, check.�� Be inspired by fabulous, Pulitzer-Prize-worthy idea, check.”

As tempting as it sounds (especially in those seasons of writer’s block) to have an ideas-on-demand app that we could tap into anytime we want, I kind of like it the way it is now.�� Not everything should be so convenient and easy.�� Some things are meant to be special.

Like Highland Park in the month of May . . .

. . . when the lilacs bloom.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike