Michael S. Fedison's Blog, page 13

March 4, 2016

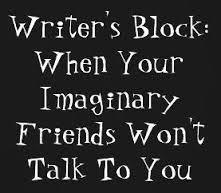

The Challenge of Writing . . . When There Are No Words

It was one of those landmark days, the kind of day where people later ask, “Where were you when that happened?” The kind of day that leaves its mark, whether you want it to or not, intractable, like a brand on your soul.

It was Tuesday, January 28, 1986, two days after I had celebrated my birthday. I was in junior high that year, and my love for all things astronomy had me fired up and eager for the events that were to take place on that cold, blustery winter morning.

It was big news and a highly anticipated moment–the launching of the space shuttle Challenger, complete with its seven-person crew, including the first teacher ever to venture into space, Christa McAuliffe. But it was a school day, after all, and at the time of the launch, I was in Earth Science class, taking a quiz. The teacher, a bald, bespectacled man in his midfifties who gave us quizzes twice a week, without fail or exception, had the radio turned on, with live coverage of the launch. It was hard to concentrate on the quiz.

At 11:38 a.m., EST, liftoff! The voices on the radio buzzed with excitement. I remember putting down my pencil, looking out the window, imagining . . .

But not for long. I didn’t want to flunk the quiz, so I proceeded to the next question. I read it once, twice, finding it hard to focus on the words. As I finally honed in on the answer, the voices on the radio began to shout. At first, I tried to ignore them. I figured they must have been excited, that’s all. But the shouting didn’t stop; it intensified. Something clearly wasn’t right.

That’s when the words, tinny, with a hint of static, filtered through the classroom. “The space shuttle Challenger has exploded!”

What? I was sure I was misunderstanding, my hearing compromised by the distance and volume–the radio was a good thirty feet away from me, and not turned up very loud. But then I looked at my desk mate, Anita. She and I had known each other since we were toddlers. We’d gone to kindergarten together, lived a half mile apart, on the same suburban street. The expression on her face told me immediately that I had not misheard.

Pandemonium on the radio. Our teacher turned the volume up, and I thought of the absurdity of trying to take a quiz at a moment like this. The flight had lasted all of 73 seconds before disaster struck. The commentators were all shouting, exclaiming, already speculating what might have gone wrong. In the desk in front of me, Joe and Tony, two good friends, looked back at Anita and me, open-mouthed, wide-eyed.

There were no words. What could anyone say? We just sat there, staring into the empty space of the room, at the radio, as if we might be able to will the reporters to say something different, or perhaps turn back time to just before the launch, and warn the crew not to fly.

There are no words. I said it again and again in my mind.

There are no words.

********************

That night, at home, I watched clip after clip of the nightmare. It stung and horrified on an almost personal level, as I had entertained the idea of becoming an astronaut when I grew up. I loved adventure, the planets, the endless blackness of outer space, the promise and mystery of a universe waiting to be discovered.

I didn’t want to continue watching the shuttle explode, over and over, but I couldn’t seem to help it. I stared at the television screen deep into the night, hoping for the impossible.

Finally I went to bed. But I couldn’t sleep. I thought of the crew–how long were they even aware that there was a problem on the Challenger? Did they have ten seconds’ warning? Five? Two? Or were they caught completely by surprise? And the families, the loved ones . . .

There are no words.

But then I thought about that. Was that really true? The destruction of the space shuttle Challenger was a catastrophe, something that would never be forgotten, but life was full of moments, both good and bad, that so often seemed beyond the purview of language. Even little things, precious things, were hard to put into words: a first kiss, moving away from home for the first time, falling in love, saying good-bye. And didn’t everyone experience their own personal canyons and tragedies? The death of a loved one, the betrayal of a close friend, the loss of a lifelong dream, blown apart like shrapnel on the wind.

How could any of these experiences be captured, truly, in words?

Life, I thought, as I lay there, awake, unable to close my eyes. How can anyone really write about life, the things that matter? The things that resonate?

Even then, as a junior high student, I knew that, for me, writing was akin to breathing. I couldn’t imagine a life without it. But most of my stories as a kid were adventures, space explorations, without much depth or emotion. I sensed I was arriving at a crossroads. The way I felt lying there, the thoughts swirling in my head, the ideas and motivations abounding, I wanted so much to be able to convey it all in a story, through the power of the written word.

Words often seemed so lacking, so trite. How could raw emotion, the depths of the heart, be expressed through them? Could they? Or was the whole thing futile?

That night, I resolved to try, to learn, to find a way. And if I didn’t, or couldn’t, I would keep trying, and never give up. I wanted to do more than just send readers on grand explorations to other planets or faraway eras. I wanted to be able to move them, to have them see themselves on the page, to laugh and cry and engage with the characters.

I thought of other stories I had read, where this wonderful thing, this literary sleight of hand, as it were, had happened, where I magically was able to relate to some black-and-white construct on the printed page, the bones and cartilage fleshed out with muscle and skin and heart, imagined and created by a writer decades, or even centuries, ago.

My hopes and goals as a writer have not changed since that long, sleepless night thirty years ago. Perhaps all writers, all artists, feel this way. We want to create something meaningful, something that reaches others and moves them, makes them laugh at the triumphs and cry at the losses, makes them pull for our characters and root for them as if they were old friends.

We want to be able to fill in the gaps, to convey on the page the pain and suffering, the gladness and joy, the broken dreams and irretrievable, lost hopes of childhood, the promise of a better tomorrow in spite of it all.

We want to write, and communicate, and share, and express . . . when there are no words.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

February 21, 2016

When a Pee-Wee-Sized Idea Turns into a Bases-Clearing Home Run

It’s happened to me more times than I can remember. An idea strikes, out of the blue, an inspiration from the creative ether, and I feel energized, inspired, eager to begin a new story.

But then a funny thing happens.

I realize, sometimes after keying in the first few sentences, sometimes while thinking about the idea more fully, before having written a single word, that my construct, this gift from the muse, is in fact woefully underdeveloped. Perhaps it represents a situation, a concept, a character’s epiphany, a new twist on an old theme–it is a good starting point for a story, but it is not, by itself and in itself, a story. Not even close. Once the white-hot glow of new creation cools to a steady simmer, once I step back and examine things with a cool and analytical eye, I realize I am nowhere close to beginning a story. There is still much to flesh out.

This is precisely what happened with The Eye-Dancers. One night, while still in high school, I had a vivid dream of a girl outside my bedroom window. She was just a child, maybe seven years old, standing in the light of the street lamp, out in the middle of the road. But she was no ordinary child–the light went right through her. She was more ghost than girl, more apparition than flesh-and-blood human being. She beckoned for me to come outside, and I remember, all these years later, how real it all seemed. When I woke up moments later, the bedsheets were in a tangle at my feet, and my skin was wet with perspiration. Immediately I jotted down the essentials of the dream, knowing, instinctively, that this was the germ of a story. The girl from my dreams couldn’t be wasted, tossed into some discarded literary oblivion from which she might never be heard from again. She needed to come alive, on the printed page, the centerpiece of a story I was sure I was meant to write.

The thing is, it took twenty years for that story to materialize, two decades for the pieces to fit together into a coherent and structured whole. Many times, I doubted if I would ever be able to work this “ghost girl” into a story, but finally, in a far-off and futuristic 21st century, Mitchell Brant and Joe Marma and Ryan Swinton and Marc Kuslanski emerged, one by one, against a backdrop of parallel worlds and nightmares come to life, and the “ghost girl” at last had a home.

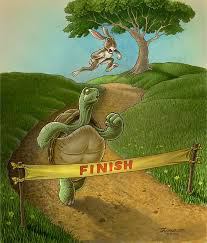

But that’s the way ideas often are. Every now and then, when we’re lucky, they arrive fully evolved, fleshed out, ready to lead us where they will. Much more frequently, at least in my experience–they come in pieces, bit by bit, at their own pace, and in their own time. They cannot be rushed, and they cannot be forced.

They demand our patience.

*******************

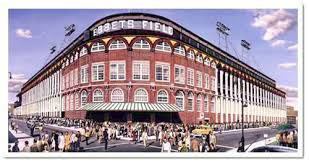

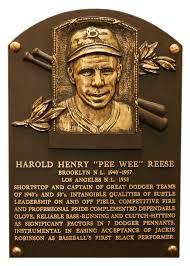

Harold “Pee Wee” Reese was so small as a child that he didn’t manage to get onto his high school baseball team until his senior year, and even then it was for only six games. Nicknamed “Pee Wee” as a boy because of his mastery of playing marbles, Reese weighed all of 120 pounds as a high school senior. Few talent scouts indeed would have predicted a future in baseball for the diminutive infielder.

But Reese continued to play the game he loved, and when his amateur church league team played their championship game on the minor league Louisville Colonels field, personnel for the minor league club were impressed by what they saw. Maybe the small kid with the slick glove and quick feet had a future in the game, after all.

Within two short years, Reese was playing shortstop for the Brooklyn Dodgers, in the Major Leagues. His big-league career got off to a rocky start, as he broke a bone in his heel during his rookie campaign of 1940, and then the following year, Reese led the Majors in errors. But as time went on, it became clear that Pee Wee Reese was a keeper. The Dodgers never traded him or released him; he would go on to play for the heroes of Flatbush for sixteen years.

Never a great pure hitter, Reese still managed to get on base with regularity, drawing walks and using his savvy to set the table as the leadoff batter in the National League’s most feared lineup, featuring the power of Duke Snider, Roy Campanella, Carl Furillo, the skill of Junior Gilliam, and the all-around mastery of Jackie Robinson. It was in regard to Robinson, in particular, where Reese made his most profound mark, helping his teammate along during Robinson’s trailblazing and tempestuous rookie year of 1947. Reese, the team captain, played such a pivotal role that Robinson later wrote, “Pee Wee, whether you are willing to admit what your being a great guy meant (a great deal) to my career, I want you to know how much I feel it meant. May I take this opportunity to say a great big thanks and I sincerely hope all things you want in life be yours.”

Pee Wee Reese retired from baseball as a player in 1958, the year after the Dodgers moved to the West Coast. (He lost three years of his career in the 1940s while serving in World War II.) In 1984, deservedly, and long overdue, the Little Colonel, the captain of the Dodgers, was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

******************

It’s easy to wish that all ideas, when they come, arrive fully formed and ready to go, complete with all major plot developments, character motivations, and even, perhaps, subthemes and story tangents. And sometimes they do. In particular, there have been times when an idea for a short story has hit me with such force, such actuality, I knew it was a winner, and all I had to do was sit down at my keyboard and let the tapestry of the idea unravel, word by word. Ideas like this are the phenoms, the high school superstars who even the most nearsighted of scouts can discern have a bright and accomplished future.

But you can’t count on them. They are the Halley’s Comets of the literary world, only coming round once every blue moon, teasing us with a glimpse, a flourish, and then vanishing, like mist, once again into the farthest depths of the cosmos.

No–most ideas take work, thought, honing, patience. It’s often easy to become frustrated with such ideas, works-in-progress as they are. But if we allow these soft-spoken and demure gems the time they need to grow and mature, we may just have a winner on our hands.

Sometimes, even a Pee Wee can make it all the way to the top.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

January 30, 2016

The True Fortune in “The Fortune Cookie”

Recently, I came across some of my old stories, written when I was still in middle school and high school–not, as today, via a keyboard and word processing program, but with a yellow mechanical pencil, the lead on the pages now faded by the onslaught of years. I’m not sure why I was rummaging about. It was one of those quiet, gray, nondescript January days in New England, when the world seems to be slumbering, taking a long nap before reemerging, green, and flowery, in the spring.

I suppose it was just something to do. I went through long-neglected boxes and plastic tubs, uncovering memorabilia, books I hadn’t flipped through in years, old school assignments, and, yes . . . old stories. Looking at the sheets of paper, realizing my handwriting had improved not at all since high school, I sat down beside a window and began to read.

The stories are decades old. Honestly, I had forgotten some of them even existed, but now, with the pages in my hands, the words before my eyes, they came back to me. Yes. “The Penny.” I hadn’t thought of that one in years! A cliched clunker with a predictable climax–though when I originally wrote it, surely I’d thought it was a nail-biter. “The Wager,” “The Martian Library,” “The Right One,” “Pea Soup on a Foggy Day” (don’t ask!). I read them all. I couldn’t put them down. It was easy to cringe at the over-the-top writing, the lack of believable characters, the flawed motives, the well-worn plot devices. Had I really liked these stories when I’d written them? But then I began to view them with a more forgiving eye. I’d just been starting out, after all. They were my first forays into a craft that takes a lifetime to hone, and even then, there is always room for improvement.

But there was more there than just words to read and critique. There were memories, old feelings that came back to the surface after being submerged for decades, hopes and dreams and ways of looking at the world when I was twelve and fourteen and seventeen.

That’s when I pulled out “The Fortune Cookie.” I remembered that one well. I had written it as a senior in high school, and back then thought of it as my best work, easily my most accomplished story at the time. I remember that summer, shortly after graduation, submitting it to a handful of magazines, hopeful, confident that one of them would accept it. They didn’t. It wasn’t the first time I’d received rejection slips–but it did hit me harder that summer. Why didn’t they like the story? Could I have been so wrong in my assessment of it? Wasn’t it any good?

Rereading it now, through the cold, hard light of two decades’ worth of perspective and experience, I am able to admit–it’s not a publishable story. It’s not entirely flawed. There are some good scenes, some taut dialogue, and the conclusion, unlike the other stories I had written as a teenager, actually does pack a punch. But it’s still the work of a beginning writer, barely finding his voice, still with so much to learn. Even today, as I write this post, there is a part of me that is tempted to revise the story, edit it, prune it, sharpen it, make it better. But I don’t. And I won’t.

“The Fortune Cookie,” for all its flaws, is irreplaceable–a piece front and center in my own personal literary time capsule. It belongs to a different era, just before the dawn of the Internet and email, and years before smartphones and social media. It was written, in that faded mechanical-pencil lead, by a teenage version of myself, approaching the story from a different angle, with a different skill set and a different point of view, than the way I’d approach it today. As frustrating as it might be to read it now, with all of its warts and fallacies and portions of illogic, “The Fortune Cookie” will remain as it is, in its original format.

I’ve never been one to keep a journal. I’m not sure why. I tried a couple of times, but quickly grew bored with it. I suppose I’ve always needed the added layer of taking my personal experiences and using them in stories that I make up, worlds that emerge from somewhere deep within my subconscious, perhaps mirroring our own, perhaps quite different. For whatever reason, I’ve always felt a need to create something new, as opposed to reporting on and writing about true events. But in doing so, I have often felt the lack of a journal as a loss. There is no record of how I felt on September 6, 1992 or June 29, 2001, or October 5, 1987. It’s hard not to lament sometimes and wish I had such things recorded, in a weathered and bound notebook that I could access anytime I wanted, that provided a peek, however brief, however terse, into the shadows of my past.

That’s when I stop myself, and come to understand the true value in the poorly written stories from my youth. When I read “The Fortune Cookie” today, there are certain passages that take me back, completely, to my senior year in high school, to the day when I hunched over the same wrinkled pages I hold now. I can remember the feelings that raced through me as I wrote the last scene, the way the pencil couldn’t move fast enough, unable to keep pace with the speed and direction of my thoughts. I can remember sitting down to write the first word, feeling inspired, fired up, and realizing, then as now, that there is no high so dizzying as a new idea that needs to be let loose onto the page. I can even remember the feelings I had as I wrote specific sentences, the onrush of adrenaline, the urging to press on.

And so, in many ways, “The Fortune Cookie,” and stories like it, are my journals–and will continue to be. I can imagine a time, thirty years hence, looking back at this very post and thinking, “Remember when?” Or rereading portions of The Eye-Dancers and recalling exactly the way I felt as I wrote the scene. It doesn’t end. It doesn’t have to be confined to a different decade or a previous century. It will go on as long as words are written, thoughts shared, and hearts and souls expressed onto the printed page.

Do you have any old stories lying around, collecting dust, hidden in a dark corner of the attic or a forgotten folder on your hard drive? When you come across them, your own “Fortune Cookies,” as it were–perhaps cringing at the words, perhaps smiling, perhaps a little of both–I hope you decide to keep them.

I know I will.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

January 14, 2016

The Paradox of Now (If “Now” Truly Exists)

It all seems so straightforward, so matter-of-fact.

We recently witnessed the passing of the torch from 2015 to 2016. Time to put away the old year and venture forth into the new, complete with resolutions, optimism, goals, and hopes. The ongoing passage of time, the catalog of days and weeks and months, would appear to be an irrefutable, self-evident, obvious truth, The clock ticks, we grow older, hopefully wiser, and nothing stands still.

But is it really so obvious? Is it really the kind of thing we can disregard as a fact so unchangeable, so plain, it’s not even worth thinking about or discussing?

Ar first blush, yes. We can glance at our calendars, our schedules, our itineraries, and know, unequivocally, that we have this time thing figured out. It is what it is, as they say.

Or maybe not.

*************

One of the themes in The Eye-Dancers has to do with the way we perceive reality. Can dreams and “real life” truly be separated by a hard, Maginot-like line of demarcation? Or are there, possibly, gaps along the edges, where the two dimensions intersect and become enmeshed?

Is the life we know, here, now, on this earth, really the only life we live? Or are there alternate versions, parallel worlds, going on beside us, without our even knowing it?

Nearly midway through The Eye-Dancers, Marc Kuslanski, the class science wiz, explains how he understands all of this . . .

“Everything in existence fits together,” he says. “The smallest subatomic particle, the worst hurricane, the largest whale, the layers upon layers of reality. All of it. And what quantum mechanics tells us is–there are infinitely multiple versions of each of us. Infinitely multiple versions of our own earth. You couldn’t even begin to count them all.”

Could it be possible that time works in a similar way?

************

Then again, what is time, exactly? Is it nothing more than our means of measuring it, slicing it up like so much fruit, into bite-sized pieces? Can it really be tamed in such a systemized, linear fashion?

We hear it often: “Don’t dwell on the past. The past is over and done. Don’t live too much for tomorrow. Tomorrow may never arrive. And, even if it does, what you do right now, in this moment, will directly affect what happens in the future anyway. Therefore, focus only on the now. Live in the moment, firmly where your feet are planted.”

Sound advice! But let’s delve a little deeper.

If we ask the question, “What is time?” then it seems to follow we must also ask, “What is ‘now’?” On the surface, the answer seems so elementary, as a certain Victorian detective might say, the question itself appears almost rhetorical. Because, of course, “now” is “now”! It can be nothing else. Right now, I am keying these words into this post (which, hopefully, you are not regretting reading!). There. I just keyed in this sentence. Now.

But wait. Can’t we slice “now” up even further? I am keying in this word, this letter, this space . . . You are reading these words, one at a time. Which of these is “now”? Should it be quantified by the minute? The second? The millisecond? The nanosecond? How precise do we need to be? This is far from a trivial question. How we measure “now” greatly affects our perception of it.

If we define the now as a minute in time–perhaps we have something to work with. A minute isn’t long, but long enough to perform many things, think thoughts, dream dreams. Living in the now, in this case, seems attainable.

But what if we define “now” as a moment, a breath, a blink of an eye, a beat of the heart, here and gone so fast that by the time it disappears, the next moment arrives, and then the next and the next and the next, one to another merging into a living, continuous, moving thing with no beginning and no end.

If we view “now” like this, time is expanded, and we view it as an eternal, something that cannot really be measured and itemized and saved. If “now” operates more like a wave than a particle, as it were, more like whitewater rapids than a still, tranquil pond, then what is this term we call time?

“The present is the ever-moving shadow that divides yesterday from tomorrow,” Frank Lloyd Wright once said.

William Faulkner added, “Clocks slay time . . . time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels; only when the clock stops does time come to life.”

Where does that leave us? Are we, like Martin Sloan in the classic Twilight Zone episode “Walking Distance,” “trying to go home again,” listening for “the distant music of a calliope, and hear[ing] the voices and the laughter of the people and the places of [our] past”?

Maybe time, as we know it, live it, define it, conceive of it, is an illusion. Maybe “now,” as opposed to something we can take hold of and posses, is, in actuality, a wisp, a billow of smoke rising against a blue winter sky, a flickering flame constantly in motion, never resting, never stationary. Tomorrow’s dreams and hopes are, in an eye-blink, yesterday’s forgotten memories, tucked away in some vaulted corner of the mind.

It is, by necessity perhaps, a mystery.

Centuries ago, Augustine may have said it best: “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks. I do not know.”

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

December 23, 2015

Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas (in St. Louis or Anywhere)!

There are magical moments in movies, in stories, in life–they become frozen in time, as it were, there to be captured, and recaptured, like old friends always ready to greet us with a hug and a smile.

There are, for example, signature moments I can recall from my past–memories, highlights, experiences that remain vivid and true, though decades may have elapsed. All I have to do is close my eyes, remember, and I am transported back, across a chasm of time and distance, as if by magic.

Favorite scenes in books, movies, television shows offer a comforting helping hand, as well, only in this case, you don’t need to remember anything. You can reread a favorite passage, rewatch a favorite scene–experiencing anew the special bond these creations share with you.

For me, one such movie is Meet Me in St. Louis, which hit the theaters in 1944 and starred Judy Garland, just five years removed from her signature role of Dorothy Gale, in The Wizard of Oz. In Meet Me in St. Louis, a period piece, Garland portrays Esther Smith, against the backdrop of the 1904 World’s Fair. Though much of the movie takes place in warmer months, I will always view Meet Me in St. Louis as a Christmas classic.

I’ve always enjoyed old movies. Even as a kid, I’d happily tune in to old black-and-white classics, films from yesteryear, featuring larger-than-life icons like Cary Grant, Clark Gable, and Katharine Hepburn. So it was no surprise, one snowy December night, when I was fourteen years old, that I was watching Siskel and Ebert. I used to watch their show every week back in the day, enjoying their analysis, their banter, their arguments. But on this night, on the eve of the yuletide, they closed their program by showing a clip from Meet Me in St. Louis.

“Here’s Judy Garland singing ‘Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,'” Gene Siskel announced–and instantly I entered into a story, a set of characters, a movie I had never seen or experienced. But none of that mattered, because when I watched that clip–Garland’s character singing one of my favorite holiday songs to Margaret O’Brien, who plays her little sister in the film–it made no difference that I didn’t know the context of the scene or how it interacted with the overall flow of the film.

All that mattered was a magical performance, a holiday classic, a song and a scene that transcended its WWII-era audience and, somehow, managed to speak to me, a teenager in western New York State, born decades after the movie was filmed.

And today, more than seventy years after Judy Garland sang “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” on the Silver Screen, may the song’s spirit and sentiment reach everyone this holiday season.

“Let your heart be light,” and may your “troubles . . . be out of sight . . . as in olden days, happy golden days of yore; faithful friends who are dear to us gather near to us once more.”

Wishing all of you a happy and joyous holiday, and a blessed and merry New Year.

See you all in 2016!

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

December 15, 2015

The Inner/Outer Writing Paradox (Or, From an Old Oak Desk in New England)

Where is your special place, the place where you block out the clutter and noise and distractions, and let your creative energy flow?

Mine is an old oak desk that my father used to use when he was a student in school, decades ago. It’s solid, heavy, and not designed for the accoutrements of 21st-century digital technology. But it’s my little oasis to think and dream and create.

My father actually passed the desk on to me while I was still living with my parents, a high school student with my eyes peeled toward the future, the promise of ten thousand tomorrows, of horizons to be explored and aspirations realized. We are old friends, my desk and I. The oak is scarred in spots, dented in others, victim to the long passage of time and the elements. But the imperfections merely serve to make it more approachable, more real, more mine.

I’ve spent countless hours sitting at the old desk, pecking away at my keyboard, working through stories and ideas and inspirations–some of which took shape and became full-bodied manuscripts and novels; others that died a quiet, gray death, falling into the oblivion of the unfinished and uncompleted.

Through it all, one thing has remained constant–the desk, my sturdy oak friend, has always offered solitude and seclusion–it’s just me, tucked away in my den. There are times, at night, the drapes drawn, the house dark and still, as if surrounded by a giant, soundproof glove, when I feel like the only person, the only creature, on earth.

Writing is a lonely task–sometimes, it seems, the loneliest of all, especially when the words won’t come, the characters won’t cooperate, the sentences and paragraphs refuse to flow into anything resembling a coherent whole.

And yet, and yet . . .

There is a paradox at work here. From the solitude, a reaching out; from the stillness, a sharing of words and thoughts and ideas–sending them out, perhaps with confidence, perhaps with trepidation, to be read and contemplated and critiqued by others. What was originally crafted in the quiet of a bedroom, the seclusion of a Thoreau-like woodland getaway, is now dispersed, as if by magic, away from the confines and isolation of self and out toward the vastness of an ocean of readers.

And yet still, there is a paradox within the paradox. I, like many writers, am a lifelong introvert. I recharge my batteries when I’m alone, lost in thought and wonder. I suppose I’ve become a bit more skilled at social gatherings through the years (though perhaps my friends may disagree!), but mingling among partygoers or making small talk in a group setting has never, and will never, come naturally to me. Much like Mitchell Brant or Marc Kuslanski, I tend to feel awkward and clumsy in such situations. When I observe my extrovert friends or family members, the effortless way they break into, or begin, conversations, I cannot help but admire them for their skills and panache. They make something I struggle with look easy.

But the funny thing is–the majority of them would likely never dare to share the intense, personal accounts we writers do on a regular basis–often, to people we don’t even know. A paradox, indeed, that an introverted writer feels the desire, the longing, the need, to become naked and vulnerable, sharing his feelings, fears, dreams, memories, foibles, passions, ideas, loves with anyone who chooses to read them.

It’s as if the solitary act of writing needs to shed its literary cocoon and fly out the window, looking for places to land. There is value, of course, even in writing just for yourself. Diaries and journals through the ages lend proof to this truth. But within every writer’s heart, isn’t there a calling, as if a voice were whispering, to share the depth and breadth of her essence? The ideas, expressed as words on a page, are disconnected from the whole, separate from the world, so long as they reside only in our computer hard drive or in a dusty corner of our dresser drawer.

And the world, as it were, may contain only a handful of readers–perhaps family members and a few close friends–or it may include everyone, the reach as limitless as our imaginations. The power of the Internet certainly offers such reach. We write a blog post in New England, or Berlin, or San Francisco, or Prague, and we, through the simplest of clicks, instantly share it across the globe. And we, more than likely, wish for our words to be read, and, hopefully, appreciated and digested and thought about, by as many people as possible.

Perhaps writers, then, are, in actuality, closet extroverts? Or, maybe more accurately, writers are people, and feel the same longing all people share–to be recognized, to be understood, to be heard. We just go about it in our own way.

We try, “in utter loneliness,” as John Steinbeck once said, to “explain the inexplicable.”

So the next time you tuck yourself away in your room or your office or your secluded writer’s cabin in the wild, and you feel a pang of guilt that you’re not spending that time with your family or your friends (a feeling I’ve certainly experienced on numerous occasions), perhaps you can offer them (and yourself) a reminder.

Tell them that you have something inside of you, insisting, unceasing, that must come out, something so personal, so inherently you, that no one else on earth can produce it. And that it’s a wistful thing, ungraspable, really, like a phantom flower that materializes out of thin air, but when reached for, vanishes like mist. All we can do, while sequestered in our little writing corner, the door shut, the phone off, is try to capture that feeling, that idea, that insistence within us and express it to the best of our abilities.

And then, when we step back out into the light of day, share it with the world.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike

November 27, 2015

Author Interview with Nicholas Conley

Recently I had the pleasure of reading Pale Highway, a novel by Nicholas Conley. Nicholas has been a longtime follower and supporter of The Eye-Dancers blog, and I am thrilled to feature him here.

In this season of thanksgiving, I am reminded of all the wonderful virtual friends I’ve made since launching this website over three years ago. As I’ve said several times in previous posts, when I began The Eye-Dancers blog, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I’d never blogged before, and was a neophyte in ever sense of the word.

The great people of WordPress welcomed me right from the start, and it’s been a pure joy to be a part of this very special community.

Nicholas was one of my earliest followers, and it’s an honor to interview him today.

If you haven’t visited his blog, I highly recommend that you do so, and his latest novel, Pale Highway, is a fantastic read and an impeccably crafted work of literature.

I hope you enjoy the interview!

*************

1. I’m always fascinated by titles. I know, for me, sometimes a title comes before I even write the first word of a story. Other times (as with the WIP I am writing now), titles are elusive, shy, hiding in the literary underbrush and daring you to find them. How was it with Pale Highway? It’s a wonderfully evocative title. Did it come to you early on in the process? Or did it come much later?

I know what you mean, I love titles. For me, I can’t even start writing a story until I know the title, because so much of my central narrative is always framed by whatever concept the title evokes. When I first started researching for Pale Highway, I spent a long time pondering possible titles, most of them relating to Gabriel’s dementia, but nothing felt like it quite captured it. Then, there was one night where I just got this lightning bolt to the head, and this title—Pale Highway—came to me out of nowhere. When it did, it was the first time I truly understood what the novel was about, and the message that Gabriel’s story had to say about the human condition.

2. In a similar vein, each individual chapter has its own title. Did that prove to be a challenge at all? Or did the chapter titles flow easily throughout the process? Did you name each chapter prior to writing it, or did some of the chapter titles come later?

Chapter titles I tend to play around more freely with, changing them as I go, and seeing what jumps out at me. Since I tend to use shorter chapters that are focused on a single idea or moment, the chapter titles will often pop out to me midway through writing the chapter.

3. It’s interesting to hear how writers tackle a long work of fiction. Before you started Pale Highway, did you have a detailed outline of each chapter? Or–did you have a more general outline, with major plot points and perhaps an ending in mind? Or did you have essentially very little idea where the story would take you, and just decided to enter into the project without any concrete or firmly predetermined plans?

I’m the sort of person who always has to-do-lists, reminders, alarms and all of that stuff, so I’m definitely a detailed outliner. I outline a long time before I even start writing, usually on a chapter by chapter basis. Once I start writing, I do give my characters and story room to break free from the outline and do what they want—which they often do—but having a basic road map helps me stay focused, and keep the narrative tight.

4. Sort of a follow-up to the previous question, but, during the writing process, were there things that occurred that greatly surprised you? For example, did a character say something or do something, almost out of his or her own volition, that you just didn’t see coming? Was there ever a twist in the plot that just “happened,” on its own as it were, and afterward, you thought to yourself, Where did that come from? In short, how many surprises did you experience during the writing of Pale Highway?

Oh yeah, those surprises are one of the best parts of writing! The plot itself stayed pretty on track all the way through, but Gabriel himself often surprised me with his cunning insights, his occasional sardonic cracks, and the decisions he made. Victor, the rather strange fellow resident who Gabriel befriends, surprised me many times as well.

5. The novel is wonderfully written and beautifully layered. It flows so well. How long did it take to write, from beginning (first-draft stage) to end (ready for publication)?

Thank you, it’s amazing to hear that. After putting so much work into it for such a long time, that sort of comment makes my day!

I started coming up with the story ideas that would lead to Pale Highway back in 2012, even before The Cage Legacy came out. These concepts went through a lot of transformation after that point, but as a whole, Pale Highway was something that I worked on for the better part of three years. I’ve been anticipating its entry into the world for a long, long time.

6. The novel explores scientific and medical ideas–they are integral to the story. How did you balance the need to provide sufficient scientific details but at the same time not inundate the reader with too much information? It would seem this is like walking a tightrope. You need enough to make the material resonate but not so much that readers’ eyes glaze over. Pale Highway accomplishes a perfect balance. Was this something you consciously “game-planned” for before writing the first draft?

You said it perfectly, about how it’s like walking a tightrope. In order to explain the scientific ideas that impact the story—and on a character level, to demonstrate what kind of person Gabriel Schist was before Alzheimer’s, as his ideas were the most defining aspect of his persona—it required that I put in just enough information about his theories to explain what they were, while also not doing a massive info dump that takes the reader out of the story. I hope that I struck a good balance.

7. The novel, through the point of view of its protagonist, Gabriel Schist, explores several fascinating theories about the immune system. Prior to writing Pale Highway, did you need to perform a lot of research on the immune system? Or was it a subject you already had studied and pursued previously?

The Alzheimer’s aspect of the novel was one that I had already researched with my own experience, working in the Alzheimer’s unit of a nursing home. Gabriel’s theories about the immune system, however, I needed to do an insane amount of new research about in order to understand. I can’t even begin to tell you how many books, essays and articles I read on the subject.

I saw it like this: if Gabriel was the kind of man who was defined by the world as a “mad genius,” then it was important that I had a good understanding of what his work was about. I also figured that in this sort of alternative reality that Gabriel lives in—a world in which he found an AIDS cure back in the 1990s—Gabriel’s theories were going to have to be unconventional, strange, something that isn’t usually explored by the establishment. Once I started reading about the work of Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, something clicked, and I knew where to focus my studies on.

8. There are several flashback chapters expertly placed throughout the story that show different sides of Gabriel, and at different periods of his life. I found it interesting (and highly effective) that most of these flashback chapters were presented in points of view that were not Gabriel’s. The chapters, therefore, not only allow us to see Gabriel at various points in his life, but they also allow us to see him through the eyes of others, rounding out our perception of him. When did you make the decision to write these flashback chapters in different points of view? Was that something you knew you wanted to do right from the start? Or did that come about later in the process?

You got it. I knew early on that for the main story line—Gabriel being an Alzheimer’s patient in a nursing home—I wanted to keep it in Gabriel’s POV, to show that world through his eyes, to show what a nursing home looks like when one is a resident suffering from a neurodegenerative disease. But on the same token, I also knew that I wanted to tell the flashbacks from the perspective of others as much as possible, so that we could get to know Gabriel as a young man in the same way that others would encounter him—brilliant, quiet, introverted—while also having that slice into his older mind, so we’re able to understand him, form a full mental picture, and hopefully relate to a character somewhat outside the norm.

9. Pale Highway is a multi-layered novel, tying together medical themes, the plight and care of the elderly, not to mention various metaphysical and even theological ideas. It is also an in-depth character study. How did such a layered idea come to you? The novel is a mosaic of so many themes. Was this an idea that came to you all at once, or did it evolve, piece by piece, over a period of years?

I knew back in 2011 that I wanted to write a book about Alzheimer’s, and with that in mind, I started piecing together what kind of book I wanted to write. Once I knew who Gabriel Schist was, I knew that the central narrative had to be centered on his final attempt at redemption, a quest to do one more meaningful thing in his life. With him being an immunologist, this meant that the clear thing to do was have him try to cure a bizarre new disease, and so the book became science fiction.

The idea of writing this book as a literary novel, or even just a sci-fi novel, seemed limiting to me. It would have prevented me from delving into the more metaphysical aspects of what I wanted to express. Because while Pale Highway is about Alzheimer’s at its core, it’s also about death, life, and what it means to be a human being. Finally writing my way to the third act of this novel, and delving into these issues, was one of the most cathartic experiences of my life.

10. What did you find to be the most challenging aspect of writing Pale Highway?

The research was the hardest part to start with, but by the time I started writing I had a good handle on that. Writing about the traumatic experiences that Gabriel goes though, as more and more pieces of his brain fall away, was painful. By the time that Gabriel’s Alzheimer’s symptoms begins to worsen, I’d developed such a connection to him that it felt much like watching a friend with Alzheimer’s, and knowing that I couldn’t do anything to help him.

11. What did you find to be the easiest aspect?

Writing about the nursing home itself, with all of its flaws, problems, humorous moments, and overall this pervading sense of bittersweet tragedy. In all honesty, I could’ve written at least 30 books about Bright New Day, the residents there, how it all works. I never see nursing homes properly represented in the media, so it was great to put that out there.

12. Who are some of your favorite authors and literary inspirations?

So many. I always say Stephen King first, primarily because reading his Dark Tower books as a teenager was one of my most inspirational experiences, and I don’t think there’s ever been another book series I’ve been so enveloped in. I also love Richard Matheson, Kurt Vonnegut, Cormac McCarthy, and Philip K. Dick.

13. If you could offer just one single piece of advice to an aspiring author, what would it be?

It’s all about perseverance. Inspiration is the electrical charge that powers your work, but perseverance is the cord that connects it to the wall.

14. What are your future writing plans? Are you currently working on a new project?

I have multiple works in progress, all in various different states of development. Part of my writing process, after finishing a first draft, is to put it aside for at least a month and then come back to it with fresh eyes, so I’ll often write another first draft between these two drafts. There’s one novel in particular that’s rising to the top right now, so I’m pretty sure that’s going to be my next book.

15. Where can readers find and download your work?

You can find me on www.NicholasConley.com, and my blog is linked to from there. You can also follow me on Twitter at @NicholasConley1. Always happy to meet new readers! I wish I could send complementary coffee cups over the net, but unfortunately technology has not yet advanced to that level. Someday, maybe…

************

Nicholas Conley’s passion for storytelling began at an early age, prompted by a love of science fiction novels, comic books and horror movies. When not busy writing, Nicholas spends his time reading, traveling to new places, and indulging in a lifelong coffee habit. In order to better establish himself on the planet Earth, Nicholas has currently made his home in New Hampshire.

To learn more about him, take a stroll over to www.NicholasConley.com.

Thank you, Nicholas, for a great interview, and thanks so much to everyone for reading!

–Mike

November 12, 2015

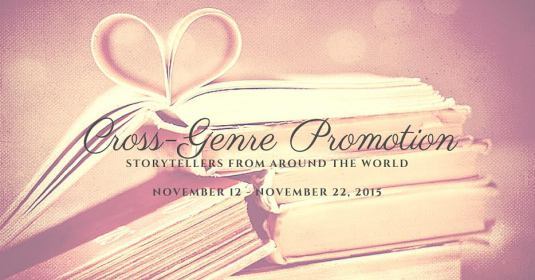

What You Need (Or, Hopefully, Want!) to Read–a Cross-Genre, Multi-Author Promotion

In the first-season Twilight Zone episode titled “What You Need,” which aired on Christmas Day 1959, an old peddler named Pedott walks into a drinking establishment, carrying with him his sack of wares.

He approaches a young woman, seated alone at a table, and asks her, “Something for you, miss?”

She hands over a bill, asking for some matches, but the old man stares at her, looks into her eyes, and exclaims, “You don’t need matches, miss. I’ll tell you what you need.” And he hands her a small bottle of cleaning fluid, “guaranteed to remove spots of any and all kinds.”

“It’s what you need,” he assures her, and she takes it, no doubt baffled by the display.

Pedott approaches the bar, where a man referred to as “Lefty” is drinking liberally.

“Whaddaya got, pop?” Lefty asks between drinks.

“Many things,” the old peddler answers. “Many odds and ends. Things you need.”

Lefty tells him there’s no chance he has what he needs in his bag full of merchandise–a new left arm.

The bartender breaks in, explaining that Lefty used to be “quite a pitcher in his time.” He even pitched a couple of years for the Chicago Cubs. But then “his arm went sour.” Now Lefty comes into the bar each night, “looking for a baseball career at the bottom of a bottle.”

Pedott tells Lefty there are other opportunities, new career paths he can pursue. Pitching isn’t the only way he can earn a living. Lefty scoffs at this, his demeanor downcast, bereft of hope.

Suddenly the old man has a brainstorm. “I think I know what it is you need,” he says, reaching into his bag and fishing out a bus ticket to Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Lefty laughs. “Now, what’s in Scranton, Pennsylvania, old man?”

But then the phone rings. It’s for Lefty–a job offer from one of Lefty’s old managers to coach for a minor league baseball team in Scranton. He tells Lefty to take a bus to Scranton and meet the GM to interview for the job.

Lefty of course wants to know how Pedott knew he’d get a call from Scranton, but the old man has quietly departed the scene, exiting the bar. Oh well. Lefty isn’t about to stress over the details. He finally has an opportunity. He just wishes he had nicer clothes.

“I sure wish I could get this out,” he gripes, pointing at a stain on his jacket. “I’d like to look halfway decent when I meet the GM.”

The woman with the just-procured cleaning fluid walks up to him, shyly saying she couldn’t help but overhear, and that she has just the thing.

She tries it on the spot, applying the fluid to Lefty’s jacket stain. “When this dries, you won’t even know you had a spot there,” she says.

As she applies the cleaning fluid, their eyes meet. There is an unmistakable attraction.

The old peddler certainly knew what each of them needed . . .

*********************

I am especially fortunate to be a part of a multi-author, cross-genre promotion that, just maybe, can give old Pedott a run for his money. The talented wordsmiths taking part in this promo offer a wide assortment of stories and styles–there is something here for everyone.

The details of the promo are straightforward. Each of the authors involved will run their own special promo on their books, beginning today and ending on November 22. What titles are they featuring in the promo and what, exactly, does their promo entail? Where can you find and download their books? I invite you to click on each of the links below to discover the answers.

I hope you enjoy this eclectic literary smorgasbord!

Barbara Monier –Contemporary Literary Fiction

John Howell — Fiction Thriller

Shehanne Moore — Historical Romance

Janice Spina –Middle-Grade Junior Detectives Series

Luciana Cavallaro –Historical Fiction–Mythology Retold

Evelyne Holingue –Middle-Grade Fiction

Jo Robinson –Nonfiction Publishing Guide for Newbies, Short Stories, and Mainstream Fiction

Sonya Solomonovich –Time-Travel Fantasy

Jennifer Chow –Adult Cozy Mystery (The beginning of a new series)

Nicki Chen –Historical Fiction–WWII China

Katie Cross –YA Fantasy

**************

As for The Eye-Dancers, as part of this joint promotion that includes authors from around the globe, I am discounting the e-book version to 99 cents, straight through to November 22. You can find it at the following online retail locations . . .

Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/The-Eye-Dancers-ebook/dp/B00A8TUS8M

B & N: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-eye-dancers-michael-s-fedison/1113839272?ean=2940015770261

Smashwords: http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/255348

Kobo: https://store.kobobooks.com/en-us/ebook/the-eye-dancers

**************

I thank each and every author involved for joining together and taking part in this cross-genre event. It is an honor to be a part of this with you.

And I thank everyone for reading!

–Mike

November 1, 2015

From Frost to Thor, with a Cup of Hot Cocoa (Or, the Literary Dualism of a New England Stick Season)

I sometimes wonder what it would be like to live year-round in balmy, gentle conditions, where palm trees sway in midwinter and heavy, insulated coats are strange accoutrements only seen on television. I’ve never experienced anything like that–not even close. I grew up in Rochester, in upstate New York, famous (or infamous, depending on your point of view) for its long winters and the lake-effect snow machine that produces blizzards and white-outs with alarming regularity.

So, what did I ultimately do? Move to Southern California, the South of France? Tahiti? Not quite. I moved to Vermont, colder and harsher still than Rochester! I have no regrets. Vermont is a rural gem, a rugged little state tucked away in the far northwest corner of New England. It’s one of the most beautiful places you will ever see. It is also, to put it mildly, a land of extremes. Few locales on earth experience such robust, exaggerated seasons–there is nothing subtle about the weather in New England. The region, according to Henry Cabot Lodge so many years ago, yet still as appropriate today as when he proclaimed it, “has a harsh climate, a barren soil, [and] a rough and stormy coast.”

And yet . . . there is one time of year in New England that is more subdued, nondescript, and soft-spoken, almost shy in its fundamental drabness . . . The month of November, tucked away in hiding for so long, creeps up on the calendar, whisper-quiet, as if inching forward on its tiptoes. And, once arrived, it has a personality, a starkness, all its own.

The flowers and blooms of spring are a distant memory, as are the ripe fields, muggy nights, and poolside gatherings of high summer. October, with its breathtaking, almost narcissistic display of reds, golds, and oranges, is still fresh in the mind’s eye, but it’s a brief performance, a limited run. The hillsides, afire with splashes of color only a fortnight ago, now lay stripped, with row on row of gray tree trunks and skeletal limbs reaching for the cold, late-autumn sky.

So, yes. In many ways, November (what the locals sometimes refer to as “stick season” around here) is a somber, even depressive month. The days grow successively shorter, colder, as the interminable New England winter approaches. There is a stillness to the land, a sharp crispness to the air, and all too often a succession of leaden-sky days with low-lying clouds hovering like bruises over the earth.

There is also, at least for me, a sense of slowing down, of stepping back, looking over the bare, windswept terrain and pausing for reflection.

It’s easy to see, walking along a Vermont country road littered with the desiccated harvest of fallen October leaves, or climbing a knoll and looking out at the ancient, rounded spine of the Green Mountains, how this area has served as an inspiration for some of the world’s great writers and poets. Something in the rocky soil, the rugged, unyielding terrain, the windswept contours of a rolling New England field in the fall instills a serious quality to an author’s prose, or a poet’s verses. Frost, Emerson, Thoreau, Plath, Hawthorne, Longfellow, Dickinson . . . the list goes on and on. Surely, there is something special about this place.

I feel it throughout the year, but at no point does it affect me more than the month of November. November brings out the serious and the brooding in my writing, makes me want to try my hand at poetry (a proclivity I rarely feel over the course of the eleven other months) and pen an introspective novel, light on the action and saturated with layered themes, obscure symbols, and tortured, existential characters. I want to reach, pursue, challenge myself to write about the subterranean undercurrents of life, raging beneath the surface, often hidden beneath a civilized and well-practiced facade. I want to produce art, works that inspire and examine, question and illuminate.

Worthy aspirations, all, but sometimes, when unchecked, they can become an albatross, long-winged and sharp-beaked, weighing me down, choking off my airflow. I appreciate the masters of the craft and serious literature as much as anyone, and hope a small smattering of my own output can be labeled “literary,” but at the same time, at least for me, there is an element even more important than the profound, more essential than the sublime.

Thankfully, the month of November also speaks to this lighter aspect.

I find November, with its protracted evenings and roaring, crackling hearth fires and frost-covered windows, to be one of the coziest times of the year. There are few treats I enjoy more on a cold fall night than preparing a mug of hot chocolate, maybe popping a generous portion of popcorn, and settling in to watch an old black-and-white classic–nothing extraordinary, not necessarily an Oscar- or Emmy-winning masterpiece, but rather something fun, silly even. Perhaps I’ll binge-watch episodes of The Honeymooners, or tune in to a corny old sci-fi movie with bug-eyed monsters, mutated spiders, or ever-expanding gelatinous blobs from outer space.

Other times, I’ll dig into my vintage comic book collection, perhaps pulling out a science-fiction title from the 1950s like Strange Adventures or Mystery in Space. If I’m feeling more superhero-minded, maybe I’ll flip through an old issue of Journey into Mystery with the Mighty Thor or, Mitchell Brant‘s favorite, The Fantastic Four. Whichever choice I make, a classic sitcom; a cliched but riveting movie produced decades ago, short on character but high on smiles; or a vintage comic complete with nostalgic ads and the musty, old smell all comic book collectors know and love, I’m just glad that Old Man November, with all its grays and dark, wistful sighs, has its lighter side to help me keep things in balance.

It’s a noble thing, a calling, really, for artists and writers and creative souls the world over to want to imbue their work with meaning and thoughts, words, and images that move their audience from tears to laughter and back again. It’s something every serious artist should have, and cultivate. But if our creative process isn’t also fun, if we don’t love what we do, that, too, will be reflected in the final output.

“Write only what you love,” Ray Bradbury once said, “and love what you write. The key word is love. You have to get up in the morning and write something you love.”

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a date with some hot cocoa, freshly popped popcorn, and a legion of telepathic crab monsters.

Thanks so much reading!

–Mike

October 17, 2015

The Lack of a Writing Calculus

I stood there, waiting, agonizing, worrying. But he would not be rushed. He would not speed-read through the story to satisfy my doubts and give me the answer he knew I wanted.

I couldn’t stand in place, so I started to pace his office, going round and round in front of his desk. He had to like the story. He had to. Dr. Sutherland was my academic advisor, had been my professor in three classes over the past two years, and knew how much I wanted to be a writer. When I’d asked him if he’d read a five-page story I’d recently completed, he agreed. I appreciated his willingness to read something that had nothing to do with the syllabus or the program. He was doing me a big favor. But now, with me wearing out the beige carpet in his small corner office, perhaps he regretted his decision.

Finally, he flipped over the last page of the story and placed it, face-up, on his desk, strewn with ungraded essays, a half-eaten ham sandwich, and a mug of cold black coffee.

I stopped pacing, waited for him to tell me what he thought. Outside his door, all was quiet in the hall. It was late afternoon on a chilly western New York November day, the trees beyond his window going bare for the coming winter.

I could stand it no longer. I coughed. “Well? Do you think it’s any good?”

He smiled, sat back in his swivel chair, put his hands behind his head. He even glanced out the window for good measure.

“You know,” he said, “writing’s a funny thing, Mike. A funny thing . . .”

I waited for him to continue. He didn’t. Was he trying to torture me? Of course, I knew his idiosyncrasies and his mannerisms well. I’d seen them on display in the classroom many times, and, generally, I liked them. But not here. Not now. My heart rate increased, and I just looked at him. I was a junior in college, but at that moment, I felt eight years old, a child seeking the approval of a respected and admired uncle.

“I remember when I was your age,” he said. There was a knowing look in his eyes. “Long time ago . . . I wanted to be a writer. Poet, really. I’d write poems about nature, love, hate, war, peace–you name it. I tried it all, experimented with form and language. Sent some of my work off to journals. Made my own chapbook. And yeah, I’d share my poems with others, ask them what you asked me just now. ‘Is it any good?’ ‘Do you like it?'” He smiled again. “Well. In my case, I guess the answer was clear enough. I’m here now, right?” He spread his arms, looked around his office. “I’m not out on Walden Pond writing prize-winning verse. But then–maybe the answer wasn’t clear. Not really. I stopped submitting after just a few rejections, told myself I had no future in it. I got my PhD, and here I am, teaching writing. It’s the path I chose, that’s all.”

I nodded. I appreciated the disclosure, but what was he saying? Where was he going with this? Was he trying to tell me, in a roundabout, oblique manner, that I wasn’t any good as a writer?

“Writing’s not like physics,” he said. “There’s no writing calculus, Mike. There are no formulas. It’s not two plus two equals four. It’s an art. It’s not a science. There is no piece of writing, in the history of the world, that is universally admired as perfect, or even great. Shakespeare has his critics. Hemingway. Show me a perfect novel. To Kill a Mockingbird? Maybe. I’d sign off on that one. But I know colleagues–respected colleagues–who dismiss it as overrated.”

He paused, as I reflected on his words. Through the window, behind him, I saw a flock of geese, flying low, their honking audible even through the glass and the walls. Flying south for the winter–if not today, then tomorrow or next week. I felt a shiver, thinking of the long, unending stretch of cold that lay ahead, the gray months of snow and frost and winds whipping in off the lake.

“Look,” Dr. Sutherland said, sitting upright in his chair now. “My opinion of your story doesn’t mean very much. Your opinion does. Is this your best work? Have you edited it two times over? Three? Four? Have you chopped every extraneous word? Did you write the story from a personal place? Does it matter to you? Those are the things that count. Everything else is just an opinion. Personal taste. Some people like Faulker. Others prefer Fitzgerald. There’s not one right answer.”

He shook his head. “That’s the beauty, and the torment, of creative writing.”

************************

I like to think I’ve matured as a writer since my junior year in college. I like to believe I’m not as reliant on the approval of others, not as much of a worrier over the work I produce. But, truth be told, I often still struggle with the same things. Sometimes when I write a blog post, or finish a new short story or chapter in a novel, I ask myself, “Yeah, but is it any good? Does it work? Will anyone really get it, or have I failed to bring out the drama, the themes, the motivations, and the meaning? Is it flat? Does it just sit there, lifeless, on the page?”

It’s something Marc Kuslanski would rail against. Marc always seeks the right answer, the factual solution to the problem. Without a formula in place to “prove” that a piece of writing is first-rate, that a scene works, that a character resonates, Marc would quickly grow frustrated.

I think, at times, all writers have a little Marc Kuslanski in them. I know I do. When writing a particular scene is akin to having a dental hygienist scrape the plaque from my teeth, when the words seem stuck and unwilling to come out, when the characters perform their own version of the literary silent treatment, I find myself wishing for a true, definable, and irrefutable writing calculus.

In moments like this, when I can’t seem to overcome the inevitable insecurities and doubts of the writing trade, I take a step back, force myself to remember the conversation I had with my academic advisor on that late fall day in the 1990s, as the twentieth century took its last, dying gasps before giving way to a new millennium. I remember his words, his advice, and I try my best to apply them.

*********************

As I turned to leave his office, Dr. Sutherland held up his hand.

“I wanted to thank you for sharing your story with me, Mike,” he said. “I know–believe me, I do–that it’s not easy.”

I didn’t know if he was finished, so I stood there a moment longer.

“Keep at it,” he said. “Don’t give up. Keep writing.”

“Thanks,” I said. I smiled. There was nothing else he might have said that would have meant as much.

Walking out into the fading November afternoon, the sun already sinking low to the west, I felt as though I were walking on air.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike