Stephen Morris's Blog, page 21

August 9, 2019

St. Roch in Lisbon–and New York!

In this interior view of the Church of St. Roch in Lisbon, you can see the famously expensive Chapel of St. John the Baptist. One reason it was so expensive os the large amount of lapis lazuli used on the front of the altar and the walls of the chapel.

My recent post about St. Roch was much more popular–and sparked some very interesting comments and responses–than I had anticipated and prompted me to think a little bit more about the good saint.

The most famous church dedicated to St. Roch is in Lisbon, Portugal. (There are a half dozen churches dedicated to him in the metropolitan area of New York City.) The church in Lisbon was the earliest Jesuit church in the Portuguese world, and one of the first Jesuit churches anywhere. The Igreja de São Roque was one of the few buildings in Lisbon to survive the disastrous 1755 earthquake relatively unscathed.

When built in the 16th century it was the first Jesuit church designed in the “auditorium-church” style specifically for preaching. It contains a number of chapels; the most notable is the 18th-century Chapel of St. John the Baptist which was constructed in Rome of many precious stones and disassembled, shipped, and reconstructed at São Roque in Lisbon; at the time it was reportedly the most expensive chapel in Europe.

The history of the church is fascinating. In 1505 Lisbon was being ravaged by the plague, which had arrived by ship from Italy. The king and the court were even forced to flee Lisbon for a while. The site of São Roque, outside the city walls (now an area known as the Bairro Alto), became a cemetery for plague victims. At the same time the King of Portugal sent to Venice for a relic of St. Roch, the patron saint of plague victims, whose body had been brought to Venice in 1485. The relic was sent by the Venetian government, and it was carried in procession up the hill to the plague cemetery.

The inhabitants of Lisbon then decided to erect a shrine on the site to house the relic. This early shrine had a “Plague Courtyard” for the burial of plague victims next to the shrine. In 1540, after the founding of the Society of Jesus in the 1530s, the king of Portugal invited them to come to Lisbon and the first Jesuits soon arrived. They settled first in All Saints Hospital (which no longer exists). However they soon began looking for a larger, more permanent location for their main church, and selected the Shrine of St. Roch as their favored site. They used the old shrine for a while but built the current church in 1555-1565.

St. Roch himself is usually represented in the garb of a pilgrim, often lifting his tunic to demonstrate the plague sore, or bubo, in his thigh, and accompanied by a dog carrying a loaf in its mouth. The Third Order of Saint Francis claims him as a member and includes his feast on its own calendar of saints, observing it on August 17. There is a popular street festival in his honor in Little Italy at the end of August each summer; read about it here.

The post St. Roch in Lisbon–and New York! appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

August 2, 2019

Maccabees and Moses and St. Peter

Statue of Moses by Michelangelo, in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. The relics of the Maccabees were kept in this same church.

The veneration of the Maccabean martyrs is unique in the Judeo-Christian tradition: they are the only martyrs commemorated by Jews and Christians alike. The seventh chapter of the Second Book of Maccabees (in the Old Testament) tells the story of seven faithful Jewish brothers who maintained their fidelity to the Law of God in the face of persecution during the tyranny of Antiochus IV in the second century B.C. The New Testament book of Hebrews commends these martyrs of Maccabees as exemplars of living faith (Heb 11:35).

These seven Jewish brothers and their mother were arrested and ordered to eat the un-kosher flesh of a pig. The horrific murder of these Maccabean martyrs was so terrible and gruesome that we derived an English word from it—-macabre.

The festival of Hanukkah in December celebrates the revolt led by the Maccabees against the Syrian emperor Antiochus IV. Christians have long commemorated the Maccabees on August 1 and the relics of the 7 Maccabee brothers, with their mother and teacher were long kept in the Church of St. Peter’s Chains (Rome). The relics were sent to Germany to be housed in a church in Cologne (the same city where the relics of the Magi are kept); evidently the Maccabean relics had been kept in Cologne before they had been sent to Rome.

By keeping the Maccabean relics and the statue of Moses in the Church of St. Peter’s Chains, we can see the connection between the Law of Moses and those Maccabean martyrs who died for refusing to abandon that Law. Even more, their memory is joined with the imprisonment and eventual martyrdom of the Apostle Peter. (We know that the festival of Hanukkah was still fairly new in the first century AD but that Jesus celebrated it with the apostles in John 10:22-23.)

You can find a very interesting article (in German!) here about the relics of the Maccabees that includes close-up photos of the golden reliquary which contains their bones. (If you open the page using Chrome, it will offer to translate the page for you–I want to thank my daughter Rebekah for teaching me that trick!)

The reliquary itself is fascinating. It was apparently made in 1500; it is a wooden box in the form of a church, covered with gilded copper plates. The walls of the shrine and top portions are composed of 40 scenes in which the story of the Maccabee brothers and their mother is placed in parallel with the suffering of Christ and His mother Mary. One of the most obvious examples is the contrast of the flagellation of the Maccabee brothers and the flagellation of Jesus. On the front of the shrine is the Coronation of Mary and the Coronation of the Maccabees, while on the back the Ascension of Christ is depicted with the heavenly glorification of the Maccabees.

The shrine for the Maccabees’ relics in St. Andrew’s Church (Cologne, Germany).

The post Maccabees and Moses and St. Peter appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

July 26, 2019

Saint Panteleimon and His Liquid Blood

Relics of St. Panteleimon/Panteleon in a German church (municipality Vogtsburg im Kaiserstuhl, Baden-Württemberg), Niederrotweil,

St Pantaleon Church (built 1735–1741).

Saint Panteleimon (known by Pantaleon during his life, he changed his name shortly before his death, meaning “all-compassionate”), is counted in the West among the late-medieval Fourteen Holy Helpers and in the East as one of the Holy Unmercenary Healers. He was a physician and a martyr who was beheaded during the Great Persecution of AD 305. After the Black Death of the mid-14th century in Western Europe, as a patron saint of physicians and midwives, he came to be regarded as one of the fourteen guardian martyrs, the Fourteen Holy Helpers.

Eastern Christian icons of St. Panteleimon show him holding a small box of medicinal herbs which he can feed a patient with a spoon which he holds in his other hand. This makes him look like an Orthodox priest, about to give Holy Communion with a spoon, which underscores the connection between “health” and “salvation;” both words share a common linguistic root. Jesus’ miracles of healing in the Gospels are taken as paradigms of salvation: to be saved is to be spiritually healed and to be healed is to be saved.

When he was beheaded, his relics–including the spilled blood–were collected and preserved. A phial containing some of his blood was long preserved in the Italian city of Ravello. On the feast day of the saint (July 27), the blood is said to become fluid and to bubble.

He was also a popular saint in Venice, and he therefore gave his name to a character in the commedia dell’arte, Pantalone, a silly, wizened old man (Shakespeare’s “lean and slippered Pantaloon”) who was a caricature of Venetians. This character was portrayed as wearing trousers rather than knee breeches, and so became the origin of the name of a type of trouser called “pantaloons,” which was later shortened to “pants”.

You can read a fascinating article about St. Panteleimon and the liquid blood relic here; be sure to scroll down the page a little to find it. There is another blood relic of St. Panteleimon kept at a monastery in Madrid; you can see a television report about it here. You can also read another blog post about other saints with similar blood relics here.

A contemporary Russian icon of Saint Panteleimon, holding his spoon to administer medicine as a priest holds a spoon to share Holy Communion with the faithful.

The post Saint Panteleimon and His Liquid Blood appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

July 19, 2019

Dog Days, Part 2–with St. Roch

A statue of St Roch made in Normandy in the early 16th century. His pilgrim’s hat is adorned with the keys of St Peter, indicating Rome as his destination. The dog which brought him food is traditionally shown at his side.

Where is St. Roch when we need him?! The summer has been especially sweltering this week in New York. The combination of heat and humidity has made it officially feel like 100+ on several days. Whew!

St. Roch, the patron of dogs, is celebrated on August 16 during the last period of the sultry Dog Days of summer. (Disease–such as plague–was thought to be especially likely to spread during the hot Dog Days so his association with both dogs and illness contributes to his association with the Dog Days of summer.) He lived from AD 1295-1327 and is invoked against the plague as well as being considered the patron saint of dogs, falsely accused people, and bachelors.

When he was 20 years old, Roch’s parents died. He distributed all his worldly goods among the poor (like Francis of Assisi) and set out as a pilgrim for Rome. Coming into Italy during an epidemic of plague, he was very diligent in tending the sick in the public hospitals and is said to have effected many miraculous cures by prayer and the sign of the cross and the touch of his hand. He himself finally fell ill. He withdrew into the forest, where he made himself a hut of boughs and leaves, which was miraculously supplied with water by a spring that arose in the place; he would have perished had not a dog supplied him with bread and licked his wounds, healing them.

St. Roch is usually portrayed with the dog licking his plague-wounds. Plague-related images of St. Roch often include the most popular symbols of plague: swords, darts, and arrows. There was also a prevalence of memento mori images, such as dark clouds and comets, which were often referenced by physicians and writers of plague tracts as causes of plague. The physical symptoms of plague–a raised arm, a tilted head, or a collapsed body–began to symbolize plague in post-Black Death painting as well.

Plague saints offered hope and healing before, during, and after times of plague. A specific style of painting, the plague votive, was considered a talisman for warding off plague. It portrayed St. Roch or another saint as an intercessor between God and the person or persons who commissioned the painting–usually a town, government, lay confraternity, or religious order to atone for the “collective guilt” of the community. Rather than a society depressed and resigned to repeated epidemics, these votives represent people taking positive steps to regain control over their environment. Paintings of St. Roch represent the confidence in which renaissance worshipers sought to access supernatural aid in overcoming the ravages of plague.

The post Dog Days, Part 2–with St. Roch appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

July 12, 2019

Dog Days, Part 1

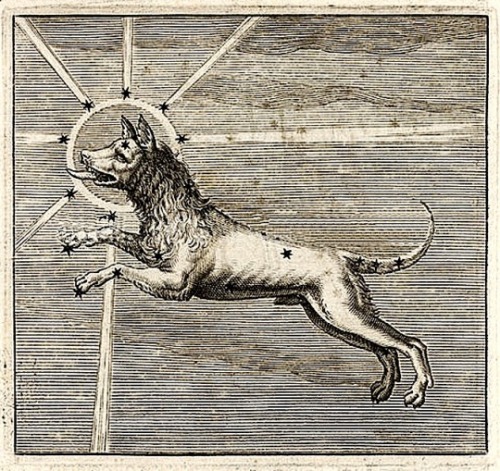

The star Sirius is part of the constellation called the “Large Dog” and is seen during the hot, sultry days of July and August.

The phrase “dog days” refers to the sultry days of summer, especially in mid-late July and August. The Romans referred to the dog days as diēs caniculārēs and associated the hot weather with the star Sirius. They considered Sirius to be the “Dog Star” because it is the brightest star in the constellation Canis Major (Large Dog); the association of the star Sirius with summer heat is found in an early Greek poem, Works and Days by Hesiod in 700 BC.

The Canis Major constellation was classically described as Orion’s dog. The Ancient Greeks thought that Sirius’s emanations could affect dogs adversely, making them behave abnormally during the long, hot “dog days.” The excessive panting of dogs in hot weather was thought to place them at risk of excessive dehydration and disease. In extreme cases, a foaming dog might have rabies, which could infect and kill humans whom they had bitten. For the ancient Egyptians, Sirius appeared just before the Nile’s flooding season, so they used the star as an indicator of the flood and associated the star with water and the wet condition of the land. Greeks and Romans, however, associated the appearing of the star with the summer wildfire season when dry fields of crops could easily be set afire by stray sparks. Their association with the star was not wet and watery but hot and dry.

Astrology associates the constellation Cancer with water and those born June 22-July 22 find it hard to achieve anything unless they feel safe and comfortable in their home lives. As such, they tend to be great at creating home environments for those that they love – both emotionally and physically. The constellation Leo (July 23-August 22) is associated with fire and those born during this period are considered theatrical and passionate people who love to bask in the spotlight and celebrate themselves. They are natural leaders.

Western Christian church calendars even noted the Dog Days. According to the 1552 edition of the The Book of Common Prayer, the “Dog Daies” begin July 6 and end August 17. The 1559 edition of the Book of Common Prayer indicates readings for July 7 and end August 18, the beginning and the end of the “Dog Daies.” This corresponds very closely to the lectionary of the 1611 edition of the King James Bible (also called the Authorized version of the Bible) which indicates the Dog Days beginning on July 6 and ending on September 5.

The post Dog Days, Part 1 appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

June 28, 2019

Deposition of the Sash of the Mother of God & The Visitation

A 17th-century Russian icon of the Deposition of the Sash of the Mother of God.

July 2 has long been a feast day of the Mother of God in both the Eastern and Western Churches although the feasts each had a somewhat different emphasis.

According to legend, the Mother of God died and was buried by the apostles in a tomb in Jerusalem. Three days later, Thomas the Apostle, who had been delayed and unable to attend the funeral, arrived and asked to have one last look at the Virgin Mary. When he and the other apostles arrived at Mary’s Tomb, they found that her body was missing. According to some accounts, the Virgin Mary appeared at that time and gave her belt (also called sash or cincture) to the Apostle Thomas. Another version of the story recounts how the Mother of God gave her sash to one of the women tending her as she was dying and the sash was passed down in that woman’s family from generation to generation.

Traditionally, the sash was reportedly made by the Virgin Mary herself, out of camel hair. Whether it was given to St. Thomas or the woman tending the dying Virgin, the sash was kept at Jerusalem for many years. It was brought to Constantinople in the 5th century, together with the robe of the Virgin Mary. The robe and the sash were both deposited in the Church of St. Mary at Blachernae. The sash was embroidered with gold thread by the Empress Zoe, the wife of Emperor Leo VI, in gratitude for a miraculous cure. The anniversary of this deposition of the sash of the Mother of God at Blachernae is celebrated every year by the Orthodox Church on July 2.

Later, the Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos (1347–1355) donated the sash to the monastery of Vatopedi on Mount Athos, where it remains to this day. (I was given a relic of the sash on Mt. Athos by a good friend of mine; I highly prize it. I have also been given a small stone from Golgotha by a parishioner and a small stone from the tomb of the Mother of God in Jerusalem as an ordination gift.)

July 2 was the traditional date for the Western Church to celebrate the Visitation of the Mother of God and St. Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist (Luke 1:39-57). Feeling the presence of his Christ in the womb of Mary, John, in the womb of his mother Elizabeth, jumped with excitement. Elizabeth greeted her cousin Mary as “the Mother of my Lord,” realizing that the baby was not just kicking in her womb for no reason. (Many western Christians moved the Visitation feast to May 31 in 1969.) Keeping the Visitation on July 2, however, strikes me as a fitting way to promote unity between Eastern and Western Christians and to foster goodwill among the adherents of a common, “mere” Christianity.

Read more about the Visitation here and here. You can read more about the Deposition here. See Mere Christianity here.

A contemporary icon depicting the Mother of God giving her sash to St. Thomas the Apostle after her Dormition (Assumption).

The post Deposition of the Sash of the Mother of God & The Visitation appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

June 17, 2019

Corpus Christi: Wafer vs. Bread

Contemporary hosts made for Holy Communion are often whole wheat and do not appear as glistening white as wafers produced with white flour.

Wafers have been used for Holy Communion by Western Christians since the late 1200s. Before that, unleavened bread–made without yeast–was used. (Western Christians adopted the use of bread without yeast in imitation of the matzah–unleavened bread–used at Passover and the Last Supper in the Gospels. The matzah was not like the crackers now sold in grocery stores; matzah and the unleavened bread used by Western Christians was more like tortilla or gyro bread.) Eastern Christians have always used bread made with yeast.

I remember in the 1970s how people joked, “It takes more faith to believe that a wafer is bread than it does to believe that it becomes the Body of Christ!” This was because the wafers do not look like anything most people think of when you ask them what bread looks like. It turns out this is because wafers are NOT technically bread at all! Both are baked goods made with flour but they are not the same just as cake and crackers are also baked goods made from flour but are not bread. Bread, by definition, is made from dough and must be kneaded and formed by hand; wafer is made from batter and is never touched until after it is baked. The first reference to Western Christians using wafers instead of bread are from the late 1200s and many people objected precisely that wafers were “not real bread.”

People also objected that the wafers were not made by monks as priests as the unleavened bread used at Mass had been. People did not think that layfolk–even nuns–should be baking the bread used for Holy Communion. (It did become common later for nuns to make wafers for churches to buy and this was a way for nuns to support themselves. Since the 1960s, making wafers for Holy Communion has become a big business that you can read about here.)

It is unclear how rapidly wafer-use spread among Western Christians but they became used uniformly across Europe by the late 1600s. Why did wafers become so popular? One reason might be that wafers did not spoil as quickly as real bread, even if it was made without yeast; this made it easier to keep the Blessed Sacrament reserved. Also, some people thought the bread or wafer used for Communion should be glistening white and it is easier to control the color of wafers than bread. Some people thought that the wafers never being touched until after they were baked was emblematic of Christ’s birth from the Virgin Mary; these people favored the use of wafers rather than bread that was touched as it was kneaded and formed.

It became standard to make a large wafer for the priest to elevate for people to reverence at the Elevation and just before Communion; the wafers that would be consumed by the layfolk were much smaller discs that were coin-sized. Preachers suggested that the coin-size wafers should remind people that God was like a vineyard owner who could hire people all day long and would pay all the workers the same coin at the end of the day (Matthew 20:1-16).

Want to know more? There are three books about the different kinds of bread used for Holy Communion:

1. Fractio Panis by Barry Craig (Germany, 2011).

2. Bread and the Liturgy: The Symbolism of Early Christian and Byzantine Bread Stamps by George Galavaris (Wisconsin, 1970).

3. The Bread of the Eucharist: Early Christian Eucharist and the Azyme Controversy, by Edward Martin (Rome, 1970).

The elevation of the Host in a contemporary celebration of the Solemn Mass by Dominican religious.

The post Corpus Christi: Wafer vs. Bread appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

June 7, 2019

D-Day … and Lidice

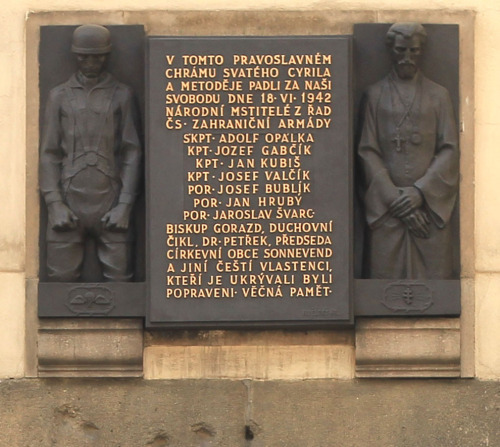

Memorial plaque for Lidice at the Orthodox cathedral of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Prague. A Gestapo report suggested Lidice was the hiding place of the assassins, since several Czech army officers exiled in England were known to have come from there.

The commemoration of the 75th anniversary of D-Day was all over the news this past week. This 75th anniversary has brought the horrors of the Nazi regime and the struggle of World War II to the consciousness of many people who are otherwise forgetful of what happened. Another anniversary of another event, also important in the struggle against the Nazi evil, is still often forgotten but deserves to be remembered.

June 10, 1942 – In one of the most infamous single acts of World War II in Europe, all 172 men and boys over age 16 in the Czech village of Lidice were shot by Nazis in reprisal for the assassination of SS leader Reinhard Heydrich. The women were deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp where most died. Ninety young children were sent to the concentration camp at Gneisenau, with some later taken to Nazi orphanages if they were German looking. The village was then completely leveled until not a trace remained.

The Nazis destroyed the town by first setting the houses on fire and then razing them to the ground with plastic explosives. They did not stop at that. Instead, they proceeded to destroy the church and even the last resting place – the cemetery. In 1943 all that remained was an empty space. Until the end of the war, the site was marked by notices forbidding entry. The news of the destruction of Lidice spread rapidly around the world.

But the Nazi intention to wipe the little Czech village off the face of the Earth did not succeed. Several towns throughout the world took the name of Lidice in memory of the Czech village that met such a horrific fate. Also, many women born at that time were named Lidice. The once tranquil village Lidice continued to live in the minds of people all over the world and after the war the Czechoslovak government decided to build Lidice again.

You can read the story of the assassination and the reprisals here. A recent movie is an excellent depiction of the historic events.

The post D-Day … and Lidice appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

May 31, 2019

St. Boniface of Mainz

The cathedral of Mainz became the ecclesiastical center north of the Alps, through the work of St. Boniface. It acquired the title of “Holy See” during the 10th century. The columnin the plaza is from the Roman period of the area; its base is adorned with small monuments to four different periods of the city’s history.

St. Boniface of Mainz was born in England and was a leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the 8th century. He organized significant foundations of the Church in Germany and was made archbishop of Mainz by Pope Gregory III. He was martyred on June 5, AD 754, along with 52 others, and his remains were returned to Fulda, where they rest in a sarcophagus which became a site of pilgrimage. He became the patron saint of Germania, known as the “Apostle of the Germans.”

St. Boniface is said to have been killed by pagans as he was chopping down one of the sacred trees they worshipped, thinking it was sacred to Odin or Thor. Boniface was known for cutting down the sacred trees and groves to demonstrate how powerless the old pagan gods were to defend their trees. He is sometimes given credit for inventing the Christmas tree as a further demonstration that the old gods were vanquished: not only could they not prevent the Christians from chopping down the sacred trees but the Christians were able to bring the trees indoors–something no devout pagan would ever do!–and use the trees to celebrate the birth of Christ.

The cathedral in Mainz, first built shortly after St. Boniface was killed, was one of the most important medieval churches north of the Alps. Besides Rome, the diocese of Mainz is the only diocese in the world with an episcopal see that is called a Holy See (sancta sedes). The Archbishops of Mainz traditionally were primas germaniae, the substitutes of the Pope north of the Alps. During the Middle Ages, the Archbishop of Mainz also had the right to crown German kings (and queens). The crowning in Mainz awarded the monarch the kingdom of Germany, and a subsequent in Rome granted him the Holy Roman Empire (this was simply a technical distinction). Once crowned in Mainz, the monarch had claim to rule Western Europe.

During the Nazi period, the Bishop of Mainz, Albert Stohr, formed an organization to help Jews escape from Germany.

The post St. Boniface of Mainz appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

May 24, 2019

May 29: A Day of Contrasts

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 signaled a shift in history and the end of the Byzantium Empire. Roger Crowley’s readable and comprehensive account of the battle between Mehmet II, sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and Constantine XI, the 57th emperor of Byzantium, illuminates the period in history that was a precursor to the current conflict between the West and the Middle East.

May 29? A day of infamy and a day of celebration!

May 29, 1453 – The city of Constantinople was captured by the Turks, who renamed it Istanbul. This marked the end of the Byzantine Empire as Istanbul became the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

May 29, 1660 – The English monarchy was restored with Charles II on the throne after several years of a Commonwealth under Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

Known as “Black Monday,” the day that Constantinople fell to the Turks, was a tragedy of epic proportions. The Ottoman Empire, established in the newly-conquered territory, allowed Jews and Christians to practice their religion but with great difficulty. Many were killed for their faith. The treatment of the Greeks and the Armenians by the Ottomans is said to have inspired Hitler’s plans for the Final Solution; “Who speaks today of the extermination of the Armenians?” Hitler asked, just a week before the September 1, 1939 invasion of Poland. An excellent study of the heartbreaking events of Black Monday can be found here.

King Charles I, the Martyr, was King of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1625 until his execution on 30 January 1649 by Oliver Cromwell, a stern and rigid Puritan. Cromwell ruled until his death from natural causes in 1658 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. The Royalists returned to power along with King Charles II in 1660, and they had Cromwell’s corpse dug up, hung in chains, and beheaded. Charles II was one of the most popular and beloved kings of England, known as the Merry Monarch in reference to both the liveliness and hedonism of his court and the general relief at the return to normality after over a decade of rule by Cromwell and the Puritans.

Also on May 29, 1913 – Igor Stravinsky’s ballet score The Rite of Spring receives its premiere performance in Paris, France, provoking a riot.

The post May 29: A Day of Contrasts appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.