Stephen Morris's Blog, page 20

October 21, 2019

St. Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs of Cologne

Statue of St. Ursula and her companions (clustered together beneath her cloak) in the church of St. Ursula in Cologne.

St. Ursula (Latin for “little bear”) was among the most popular saints of Western Europe during the Middle Ages. She and her companions–later versions of her life story report that she had 11,000 women with her although there were doubtless a much smaller group of women actually with her, probably 11 that was later expanded by a error in transcription–travelled to Cologne from Wales and were martyred in Cologne; there are records indicating that the women were executed AD 400.

The church of St. Ursula in Cologne is Romanesque, built in the 11th century atop the ancient ruins of a Roman cemetery, where the virgins associated with Saint Ursula are said to have been buried. The church has an impressive reliquary created from the bones of the former occupants of the cemetery. It is one of the twelve Romanesque churches of Cologne and was designated a basilica in the canonical, if not architectural, sense in June 1920.

The “Golden Chamber” of the church contains the remains of St. Ursula and her companions who are said to have been killed by the Huns. The walls of the Golden Chamber are covered in bones arranged in designs and letters along with relic-skulls. The exact number of people whose remains are in the Golden Chamber remains ambiguous but the number of skulls in the reliquary is greater than 11 and less than the 11,000. These remains were found in 1106 in a mass grave and were assumed to be those of the legend of St. Ursula and the virgins. Therefore, the church constructed the Golden Chamber to house the bones.

The small village of Llangwyryfon, near Aberystwyth in west Wales, has a church dedicated to St. Ursula. The village name translates as ‘Church of the Virgins’. She is believed to have come from this area. The Order of Ursulines, founded in 1535 by Angela Merici, and devoted to the education of young girls, has also helped to spread Ursula’s name throughout the world. St. Ursula was named the patron saint of school girls.

It has been theorized that the character of St. Ursula is a Christianized form of the Norse goddess Freya, who welcomed the souls of dead maidens. Other 19th-century scholars have referred to the goddesses Nehalennia, Nerthus and Mother Holda.

The post St. Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs of Cologne appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

October 11, 2019

Walsingham and Prague and Loreto… and Nazareth

Detail from the marble chapel built around the Prague replica of the Holy House from Nazareth. Construction started in 1626 and the Holy House was blessed on 25 March 1631.

The marble facade of the Holy House in Loreto, Italy is very similar to the marble facade of the Holy House in Prague.

Everyone agrees that Jesus grew up in Nazareth. He lived there with the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph. So how can so many places in Europe claim to have the Holy House of the Virgin Mary?

There was a chapel of the Virgin in Loreto, Italy since the late AD 1200s. It contained a small replica of the house in Nazareth for the faithful to visit if they could not go on pilgrimage to the Middle East. Monks (often referred to as “angels”) brought a few stones from Nazareth to add to the Holy House in Loreto. During the Renaissance, an elaborate marble façade was built around the Holy House to protect it and then a large church was built around the marble chapel. “Our Lady of Loreto” is the title of the Virgin Mary with respect to the Holy House of Loreto and her statue, carved from Cedar of Lebanon, is a “Black Madonna” (owing to centuries of lamp smoke).

Other replicas of the Holy House were constructed in many places. The most famous are in Prague and Walsingham. (The Holy House in Walsingham was destroyed by order of King Henry VIII but new shrines of the Mother of God were built there in the late 1800s and early 1900s.) The original statue of the Mother of God was thought to be destroyed when the Holy House–often called “England’s Nazareth”–was destroyed but it might have been cleverly hidden instead. A statue of the Virgin in the Victoria and Albert Museum might be the original; read about it here.

The post Walsingham and Prague and Loreto… and Nazareth appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

October 4, 2019

Protection of the Mother of God (Part 2)

A medieval bas relief in Venice of the Mother of God protecting the faithful gathered under her veil.

An archway atop a small pedestrian bridge in Venice depicts the Mother of God protecting the faithful with her veil.

Western Christian depictions of the Protecting Veil of the Mother of God are often called “the Virgin of Mercy” and are sometimes associated with Christ’s remarks that He “longed to gather your children [the people of Jerusalem] together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings….” (Matthew 23:37) The Mother of God is shown with the faithful of many social ranks and classes gathered on their knees beneath her outstretched cloak. As she is the bridge that unites earth to heaven, having nurtured Christ in her womb and giving birth to God-made-man, her image is frequently seen near bridges. (The Latin word for “priest” (pontifex) comes from the Latin for bridge-builder because priests also act as bridges between Heaven and earth, divinity and humanity.

Probably the oldest Western version of this image is a small panel by Duccio of c. 1280, with three Franciscan friars under the cloak, in Siena. The Franciscans seem to have been devoted to the idea of the Virgin’s protecting veil and were important in spreading this form of iconography, which remains important in much of Latin America.

The image of Our Lady in Walsingham was not the Virgin of Mercy with her protecting veil but the shrine of Walsingham did celebrate the feast of Our Lady of Mercy as its patronal feast day. The popularity of the Walsingham shrine led many to call England “the dowry of the Virgin” and thus celebrate the Virgin of the Dowry on the same day as well.

The importance of the Virgin’s mercy and protection underlines the communal nature of Christianity and the dependence of the faithful on each other–as well as on particular saints–in times of adversity. In the gospel, it is rare that a sick person is healed because of their own faith; usually the sick are healed because their friends had the faith to approach Christ and ask that He heal the sick or cast out the demon(s) from the possessed. It is the faith of their friends which heals and saves those most in need.

The post Protection of the Mother of God (Part 2) appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

September 27, 2019

Protection of the Mother of God (Part 1)

A medieval icon of the Protecting Veil of the Mother of God from Novgorod, currently in Moscow.

The Protecting Veil (or more simply, the Protection) of the Mother of God is one of the most popular festivals of the Slavic churches. Known as “Pokrov,” is celebrated on October 1. It commemorates a 10th century vision at the Blachernae church in Constantinople where several of her relics (her robe, veil, and part of her belt) were kept. On Sunday, October 1 at four in the morning, St. Andrew the Blessed Fool-for-Christ, who was a Slav by birth, saw the dome of the church open and the Virgin Mary enter, moving in the air above him, glowing and surrounded by angels and saints. She knelt and prayed with tears for all faithful Christians in the world. The Virgin Mary asked Her Son, Jesus Christ, to accept the prayers of all the people entreating Him and looking for Her protection. Once Her prayer was completed, she walked to the altar and continued to pray. Afterwards, she spread Her veil over all the people in the church as a protection.

St. Andrew turned to his disciple, St. Epiphanius, who was standing near him, and asked, “Do you see, brother, the Holy Theotokos, praying for all the world?” Epiphanius answered, “Yes, Holy Father, I see it and am amazed!” In the icon of this event, we see the Mother of God standing in the midst of the church with her arms reaching out in prayer and her veil stretching out between her hands. The angels and saints surround her. Below, St. Andrew the Fool for Christ is depicted, pointing up at the Virgin Mary and turning to his disciple Epiphanius.

According to the Primary Chronicle of St. Nestor the Chronicler, the inhabitants of Constantinople called upon the intercession of the Mother of God to protect them from an attack by a large Rus’ army (Rus’ was still pagan at the time).

The Pokrov icon may be related to the Western Virgin of Mercy image, in which the Virgin spreads wide her cloak to cover and protect a group of kneeling supplicants (first known from Italy at about 1280).

The post Protection of the Mother of God (Part 1) appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

September 20, 2019

Tracts for the Times: “Remember your calling!”

The series Tracts for the Times urged the English clergy to remember that they were priests of God rather than minor functionaries of the British government.

I have always been a firm believer in the power of tracts to educate people and that such education can produce results in changed lives. In my parish, I wrote several tracts that were available in the back of the church; many of these proved to be extremely popular and were reprinted several times. Another series of church tracts, the Tracts for the Times, were even more popular and led to significant changes in the Church of England.

The first of the Tracts for the Times, a series of 90 pamphlets to educate English Christians about Church history as well as classic Christian belief and practice, appeared on September 9, 1833. The tracts were widely available and very inexpensive; the popularity of the tracts, produced by the leaders of the Oxford Movement who wanted the Church of England to reclaim her status as a Church and not simply the “Religious Department” of the British government, resulted in many people using the name “Tractarian” to refer to this movement to restore pre-Reformation thought and practice.

The first 20 tracts appeared in 1833, with 30 more in 1834; the series concluded with Tract 90 in 1841. After that the pace slowed, but the later contributions were more substantive on doctrinal matters. Initially these publications were anonymous, pseudonymous, or reprints from theologians of previous centuries. The authorship details of the tracts were recovered by later scholars of the Oxford Movement. The tracts also provoked a secondary literature from opponents. Significant replies came from evangelicals, including that of William Goode in “Tract 90 Historically Refuted” (in 1845) and others.

Tract 1, by John Henry Newman, was primarily addressed to English clergy and urged them to remember that they were priests of God and not simply functionaries of the British government. The tract mourned that too many clergy were more concerned about social status and privilege than with preaching the Gospel, teaching their people, and celebrating the services of the Church. The tract urged the clergy to remember that they were ordained in the Apostolic Succession and that this gift was not to be taken lightly.

“Therefore, my dear Brethren, act up to your professions. Let it not be said that you have neglected a gift; for if you have the Spirit of the Apostles on you, surely this is a great gift: “Stir up the gift of God which is in you.” Make much of it. Show your value of it. Keep it before your minds as an honorable badge, far higher than that secular respectability, or cultivation, or polish, or learning, or rank, which gives you a hearing with the many. Tell them of your gift…. Speak out now, before you are forced, both as glorying in your privilege, and to ensure your rightful honor from your people. A notion has gone abroad, that they [British politicians] can take away your power. They think they have given and can take it away. They think it lies in the Church property, and they know that they have politically the power to confiscate that property. They have been deluded into a notion that present palpable usefulness, [measurable] results, acceptableness to your flocks, that these and such like are the tests of your Divine commission. Enlighten them in this matter. Exalt our Holy Fathers the Bishops, as the Representatives of the Apostles, and the Angels of the Churches; and magnify your office, as being ordained by them to take part in their Ministry.”

The tract warned that there was a coming conflict. The conflict would be between those who considered the Church of England to be the Body or Bride of Christ and those who thought the church was simply a convenient institution to be amended however they saw fit. These two radically opposed viewpoints would force clergy to take a stand and the tract warned clergy that they would face the consequences of their choice align with one side or the other on Judgement Day.

The post Tracts for the Times: “Remember your calling!” appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

September 13, 2019

Nazis Pervert the Swastika

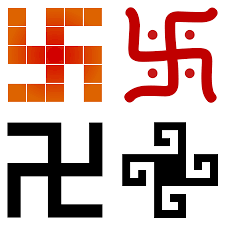

Various depictions of the swastika, a sign of life and health, which was adopted by the Nazis in 1935. The swastika is now seen by most as the infamous emblem of the most pernicious evil in human history.

The swastika, an ancient symbol of life and health, was adopted by the Nazi regime as their official logo on September 16, 1935. The symbol is now seen by most people as exclusively the emblem of the most wicked political system ever devised.

The swastika–the name swastika comes from Sanskrit word swastik, which means ‘conducive to well being’ or ‘auspicious’–is an icon which is widely found in human history. In northern Europe it has also been called a sun-wheel. A swastika generally takes the form of a cross, the arms of which are of equal length and perpendicular to the adjacent arms, each bent midway at a right angle. The earliest known swastika is from 10,000 BC found in the Ukraine. (It was engraved on wooden monuments built near the final resting places of fallen Slavs to represent eternal life.)

In several major religions, the swastika symbolizes lightning bolts, representing the thunder god and the king of the gods, such as Indra in Vedic Hinduism, Zeus in the ancient Greek religion, Jupiter in the ancient Roman religion, and Thor in the ancient Germanic religion.

Some say the swastika represents the north pole, and the rotational movement around the center or axis of the world. It also represents the Sun as a reflected function of the north pole. It is a symbol of life, of the life-creating role of the supreme principle of the universe, the absolute God, in relation to the cosmic order. Medieval Christians used it a way to depict the life-giving power of the True Cross on which Jesus was crucified and destroyed Death.

The Nazis’ principal symbol was first the hakenkreuz, “hooked-cross” (which resembles the Swastika) which the newly established Nazi Party formally adopted in 1920. The emblem was a black swastika (hooks branching clockwise) rotated 45 degrees on a white circle on a red background. This insignia was used on the party’s flag, badge, and armband and became the flag of Germany in 1935.

The post Nazis Pervert the Swastika appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

September 6, 2019

“Happy Birthday!” to the BVM

The Nativity of the Virgin by Andrea di Bartolo (1360/70 – 1428). He was an Italian painter, stained glass designer, and illuminator of the Sienese School mainly known for his religious subjects. He was active between 1389–1428 in the area in and around Siena. (This painting hangs in the National Gallery)

A feast in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary’s birth seems to have been held in Syria and Palestine in the sixth century. This celebration was accepted and adopted by the Roman Church at the end of the seventh century. It spread very slowly through the rest of Europe but by the twelfth century, it was observed throughout both Western and Eastern Europe as one of the major feasts of Mary. It remained a holy day of obligation among Roman Catholics until 1918.

In many places of central and eastern Europe the Feast of Mary’s Nativity is traditionally connected with ancient farming customs and celebrations, much like Thanksgiving Day in the U.S. September 8 itself marks the end of the summer in popular reckoning; September 8 also marks the beginning of “after-summer” and the start of the fall planting season. A blessing of the harvest and of the seed grains for the winter crops is performed in many churches.

In central and northern Europe, according to ancient belief, September 8 is also the day on which the swallows leave for the sunny skies of the South.

In the Alps, the “down-driving” (Abtrieb) begins on September 8. Cattle and sheep are taken from their summer pastures on the high mountain slopes where they have roamed for months, and descend in long caravans to the valleys to take up their winter quarters in the warm stables. The animals at the front of the procession wear elaborate decorations of flowers and ribbons; the rest carry branches of evergreen between their horns and little bells around their necks. The shepherds and other caretakers accompany the procession, dressed in all their finery and decorated with Alpine flowers, yodeling, and cracking whips to provoke a multiple echo from the surrounding mountain cliffs. Arriving at the bottom of the valley in the evening, they find the whole village or town awaiting them in a festive mood. Ample fodder is served to the cattle in the stables, and each family has a banquet that includes the farm hands. In some sections of Austria all the milk obtained on Drive-Down Day is given to the poor in honor of our Lady, together with the meat, bread, and pastries left over from the feast in the evening.

If, however, the farmer who owns the cattle has died during the summer, the “downdriving” is performed without decorations and in silence. Each animal then wears a mourning wreath of purple or black crepe.

In the wine-growing sections of France, September 8 is the day of the grape harvest festival. The owners of vineyards bring their best grapes to church to have them blessed; in Greece, the first grapes are ripe a month earlier so the Greeks bring the grapes into church to be blessed on August 6; the French have the grapes blessed and afterward tie some of them to the hands of the statue of the Virgin. The Feast of Mary’s Nativity is called “Our Lady of the Grape Harvest” in those sections, and a festive meal is held at which the first grapes of the new harvest are consumed.

The post “Happy Birthday!” to the BVM appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

August 30, 2019

St. Aidan of Lindisfarne, a Model Pastor

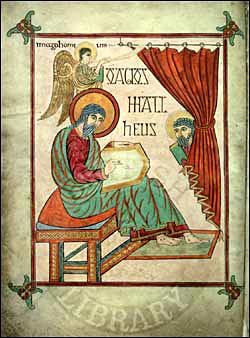

Full-page miniature of the Evangelist Saint Matthew, accompanied by his symbol, a winged man blowing a trumpet and carrying a book; folio 25v of the Lindisfarne Gospels produced about 100 years after St. Aidan founded the monastery.

St. Aidan of Lindisfarne (died 31 August AD 651) was an Irish monk and missionary credited with restoring Christianity to northern England. He founded a monastic cathedral on the island of Lindisfarne and served as its first bishop. He travelled throughout the countryside, spreading the gospel to both the Anglo-Saxon nobility and the socially disenfranchised (including children and slaves).

In the years prior to Aidan’s mission, Christianity, in northern England was being largely displaced by Anglo-Saxon paganism. However, the young king Oswald vowed to bring Christianity back to his people—an opportunity that presented itself in AD 634, when he gained the crown of Northumbria. King Oswald requested that missionaries be sent from the monastery of Iona in Scotland. At first, they sent him a bishop named Cormán, but he alienated many people by his harshness, and returned in failure to Iona reporting that the Northumbrians were too stubborn to be converted. Aidan criticized Cormán’s methods and was soon sent as his replacement. Aidan became bishop in AD 635.

Allying himself with the pious king, Aidan established a monastic community on the island of Lindisfarne, which was close to the royal castle, as the seat of his diocese. An inspired missionary, Aidan would walk from one village to another, politely conversing with the people he saw and slowly interesting them in Christianity:

“He was one to traverse both town and country on foot, never on horseback, unless compelled by some urgent necessity; and wherever in his way he saw any, either rich or poor, he invited them, if infidels, to embrace the mystery of the faith or if they were believers, to strengthen them in the faith, and to stir them up by words and actions to alms and good works. … This [the reading of scriptures and psalms, and meditation upon holy truths] was the daily employment of himself and all that were with him, wheresoever they went; and if it happened, which was but seldom, that he was invited to eat with the king, he went with one or two clerks, and having taken a small repast, made haste to be gone with them, either to read or write. At that time, many religious men and women, stirred up by his example, adopted the custom of fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays, till the ninth hour, throughout the year, except during the fifty days after Easter. He never gave money to the powerful men of the world, but only meat, if he happened to entertain them; and, on the contrary, whatsoever gifts of money he received from the rich, he either distributed them, as has been said, to the use of the poor, or bestowed them in ransoming such as had been wrong fully sold for slaves. Moreover, he afterwards made many of those he had ransomed his disciples, and after having taught and instructed them, advanced them to the order of priesthood.” (Venerable Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. Book III: Chapter V)

His pastoral emphasis on prayer, fasting, Christian education and his own personal humility is similar to all the famous pastors such as St. John of Kronstadt and the Cure d’Ars.

There are four wells associated with St. Aidan which are said to work miracles of healing, especially of asthma and skin diseases.

He is known as the Apostle of Northumbria and is recognised as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Catholic Church, and the Anglican Communion.

The post St. Aidan of Lindisfarne, a Model Pastor appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

August 24, 2019

St. John the Baptist Beheaded

This Coptic icon for the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, shows St. John ‘in clothing of camel’s hair’, with a cross (here in the Coptic Tau (T) form), beholding his own head. The axe at right refers to this line from his own preaching: “And even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Therefore every tree which does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.” [Mt 3.10; Lk 3.9]

Western and Eastern Christians commemorate of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist on August 29. However, in Italian folklore the story of the daughter of Herodias became attached to June 23, St John’s Eve, which is the night before the Feast Day of St. John the Baptist, June 24. (Usually, a feast day of a saint commemorated the death of that saint to celebrate her/his martyrdom; the feast of St. John the Baptist is one of the very few saints’ days to mark the anniversary of a saint’s birth. Click here for my earlier post about St. John’s Nativity and Midsummmer. Click here for another post about Midsummer and St. John’s Wort.) In Rome, youths would gather in front of the cathedral of Basilica of St. John Lateran on the night of June 23, because Herodias traveled in the air.

“Salome of the Seven Veils” is the name by which the “daughter of Herodias” is generally known in modern American culture. J.B. Andrews in his 1897 folklore article (Neapolian Witchcraft, Folklore Transactions of the Folklore Society, Vol III March, 1897 No.1) wrote:

It is believed that at midnight then [St. John Baptist’s Eve, June 23] Herodiade may be seen in the sky seated across a ray of fire, saying:

” Mamma, mamma, perche` lo dicesti?”

“Figlia, figlia, perche’ lo facesti? “

“Herodiade” or “Erodiade” is the Italian version of the name Herodias.

Sabina Magliocco in her incredible article Who Was Aradia? The History and Development of a Legend, The Pomegranate (see The Journal of Pagan Studies, Issue 18, Feb. 2002) explained what Herodiade was doing in the airs on June 23, the Eve of St. John Baptist’s Feast Day:

According Sabina Magliocco, there was an early Christian legend or folklore derived from the bibical account (Matthew 14:3-11, Mark 6:17-28) of Herodias and Herodias’ daughter. When the head of the saint was brought forth on a platter, she-who-danced-for-the-head-of-the-Baptist had a fit of remorse, weeping and bemoaning her sin. A powerful wind began to blow forth from the saint’s mouth, so strong that it blew the famous dancer up into the air, where she is condemned to wander.

Titus Flavius Josephus, a first-century Jewish historian provides the name of stepdaughter and niece of Herod Antipas as Salome, but Josephus makes no mention of the infamous dance. Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews recounted that after the excution of John that Herod, Herodias, and her daughter Salome were exiled Lugdunum, near Spain.

However, the name “Salome” does not appear in the biblical accounts of the beheading of John the Baptist. In the Latin Vulgate Version, the girl is refered to as the “daughter of the said Herodias.”

At some point, the “daughter of Herodias” and “Herodias” became conflated in folklore in early medieval Europe.

Probably because the holiday of St John the Baptist was widely celebrated during the Middle Ages, a great deal of religious folklore surrounds Herodias. Magliocco also explained:

Diana in the Canon Episcopi, a document attributed to the Council of Ancyra in 314 CE, but probably a much later forgery, since the earliest written record of it appears around 872 CE (Caro Baroja, 1961:62). Regino, Abbot of Pr¸m, writing in 899 CE, cites the Canon, telling bishops to warn their flocks against the false beliefs of women who think they follow “Diana the pagan goddess, or Herodias” on their night-time travels. These women believed they rode out on the backs of animals over long distances, following the orders of their mistress who called them to service on certain appointed nights. Three centuries later, Ugo da San Vittore, a 12th century Italian abbot, refers to women who believe they go out at night riding on the backs of animals with “Erodiade,” whom he conflates with Diana and Minerva (Bonomo, 1959:18-19).

Eventually there developed a widespread belief that Herodias was a the supernatural leader of a supposed cult of witches, apparently asociated with or synonymous with the legendary witch-queens Diana, Holda, Abundia, and many others. In Italy, Raterius of Liegi, Bishop of Veronia in the 9th century c.e. complained that many folk believed that Herodias was a queen or goddess and that they also claimed a third of the earth was under the dominion of Herodias. Herodias was supposed to preside over the night assembly or night flight.

In parts of Italy, the dew formed on St. John’s Eve was often said to represent the tears of the daughter of Herodias. This dew was believed to have healing virtues and promote fecundity. June 23 was also known as la notte delle streghe. It was once customary in Rome to build bonfires outside the Basilica of St. John Lateran in anticipation of the night flight led by Herodias. (Read my previous post on the bonfires of June 23 here.)

The post St. John the Baptist Beheaded appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

August 16, 2019

St. Agnes in Navona

The shrine and relic (skull) of St. Agnes in the church of St. Agnes on the Piazza Navona.

The church of St. Agnes “in Agone” is a stunning 17th-century church in Rome, Italy. It faces onto the Piazza Navona, one of the main urban spaces in the historic center of the city and the site where the early Christian Saint Agnes was martyred in AD 304 at the ancient Stadium of Domitian. Construction of the modern church began in 1652 at the instigation of Pope Innocent X whose family palace, the Palazzo Pamphili (currently rented out to serve as the embassy of Brazil) is next door to this church. The church was to be effectively a family chapel annexed to their residence (for example, an opening was formed in the drum of the dome so the family could participate in the religious services from their palace).

The name of this church–St. Agnes in agone— is unrelated to the ‘agony’ of the martyr: “in agone” was the ancient name of Piazza Navona (“piazza in agone”), and meant instead, in Greek, ‘on the site of the competitions’, because Piazza Navona was built on the site of an ancient Roman stadium which was used for footraces. From ‘in agone’, the popular use and pronunciation changed the name into ‘Navona’, but other roads in the area kept the original name.

Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers is situated in front of the church. It is often said that Bernini sculpted the figure of the “Nile” covering his eyes. (The four rivers are those which were thought to flow out of Paradise–the Garden of Eden–to bring fresh water to the rest of the world.)

The other church of St. Agnes in Rome — the Church of St. Agnes outside the Walls (Sant’Agnese fuori le mura)–is built outside the ancient walls of Rome atop the Catacombs of Saint Agnes, where the saint was originally buried, and which may still be visited from the church. Most of her relics are still there; only her head is at the Piazza Navona church. (I was recently given The Geometry of Love, a wonderful book by Margaret Visser about this church “outside the walls.” I highly recommend it!)

A view of the high altar in the church of St. Agnes on the Piazza Navona in Rome.

The post St. Agnes in Navona appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.