Lara Vesta's Blog, page 4

September 11, 2017

Listening to Spirits

In March of 2016, I was at my parent's house in southern Oregon dreaming. In the dream I received a job offer from Pacific University and was ecstatic--I love teaching and had taught for five years, from 2007-2012, before taking time away to care for my children and start a business. The promise of a regular paycheck, benefits and a return to the collegiality and support of academia was, I believed, a Goddess-sent remedy for years of poverty cycles. Plus, I was enrolled in a PhD program in Philosophy and Religion at CIIS, focusing on Women's Spirituality. I loved the program and the education I was receiving aligned with my long term goals: to bring spirituality--specifically non-religious ritual and earth-based community practice--into a higher education environment. I had done this as a lay person for years, using ritual in all of my university English classes with great effect. And I had created a course called Community Stories, which used ritual to build a container for personal/social/cultural story examination and the creation/implementation of a civic engagement project. I loved my work.But physically, I had struggled to sustain a full-time teaching schedule ever since I had a bacterial infection in 2009, two years after I started teaching. Combined with long distance parenting, blended family making and advocating for my son, who is on the autism spectrum, full-time teaching became more burdensome each year. Especially challenging was the fact that as a term employee I was used to mop up courses senior faculty were only required to carry as a small portion of their course load, mostly required, writing intensive classes like Expository Writing and First Year Seminar. While I loved--truly loved--teaching those classes, helping non-writers tell their stories in engaging ways, the amount of grading made the course hours drift long beyond the time spent teaching and prepping. There are a variety of strategies professors use to get around reading tons of papers, including peer review and bookend grading (reading just the introduction and conclusion of a work) but this was not the culture of Pacific. Nor is it a personal characteristic. I care about my students too much to not read their work.By the time I left teaching I was burnt out and disheartened. Self-employment was hard, too, but once I found my niche (community teaching, go figure) after years of various endeavors (ceremonial celebrant, spiritual business consultant), I could craft a schedule supportive of my fatigue and mostly avoid the worst crashing. It's called coping, and it is a good strategy. But I didn't know what I was coping with just yet. So when I took on graduate school, ok, that was a lot to bring in to an already full life, I started having unusual symptoms. By the time I was dreaming at my parent's house in March of 2016, I had uterine fibroids, a cyst on my liver, a cyst on my ovary and a sinking sense that something was pretty wrong in my physical body. In the dream I received the job offer from Pacific, and I was joyful. But then I looked at the dream's version of my schedule. It was ALL writing intensive courses. The spirits said, no way, and I said, oh well, it was worth looking at. But I knew in the dream it would be a bad idea to take on such a schedule. I knew.When I woke up, I had an email with a job offer from Pacific and a schedule JUST like the one in my dream. Can you guess what I did?***I took the job. I became very sick. I still haven't recovered, almost a year later.***Spirit came to me in a dream this summer, on the full moon of August. A woman insisted that I teach a class in Ancestral Connection, a topic close to my heart and a big part of my own spiritual path. I told her I don't teach anymore. She would not let it go. Finally I said I would teach it, and with the pull of spirit led timing, was told it needed to begin on the first of November and proceed for four Wednesdays. When I woke up I checked the calendar. November 1 is on a Wednesday. Okay.I could choose to not listen. I'm in another big transition right now. We are moving out of the city, where I've lived for the past decade, where my husband works, where two of my children go to school. We are moving in large part because I can't work consistently, I still haven't improved in the way we've hoped and we are having to accept that dealing with my ME/CFS might be a long process. We can't afford to live here on one income. We could barely afford it on two. The move is daunting, my energy low. To live with spirit is to listen. I am a dreamer, I receive information in my dreams. Not just symbolic illusion, but clear communication. It is a pathway for my ancestors--one of many. The woman in my dream demanded I teach, never mind I've given it up, never mind the timing. If I follow, the wyrd weaves pattern. If I resist, it knots and twists, new paths emerge. Some take me to the same place, the hard way.Ancestral Connectionis offered by donation with a suggested contribution of $100 to help my family transition into our new living situation. Support your local wyrd sister. Lean on in, let's listen together.By this and every effort may the balance be regained.

In March of 2016, I was at my parent's house in southern Oregon dreaming. In the dream I received a job offer from Pacific University and was ecstatic--I love teaching and had taught for five years, from 2007-2012, before taking time away to care for my children and start a business. The promise of a regular paycheck, benefits and a return to the collegiality and support of academia was, I believed, a Goddess-sent remedy for years of poverty cycles. Plus, I was enrolled in a PhD program in Philosophy and Religion at CIIS, focusing on Women's Spirituality. I loved the program and the education I was receiving aligned with my long term goals: to bring spirituality--specifically non-religious ritual and earth-based community practice--into a higher education environment. I had done this as a lay person for years, using ritual in all of my university English classes with great effect. And I had created a course called Community Stories, which used ritual to build a container for personal/social/cultural story examination and the creation/implementation of a civic engagement project. I loved my work.But physically, I had struggled to sustain a full-time teaching schedule ever since I had a bacterial infection in 2009, two years after I started teaching. Combined with long distance parenting, blended family making and advocating for my son, who is on the autism spectrum, full-time teaching became more burdensome each year. Especially challenging was the fact that as a term employee I was used to mop up courses senior faculty were only required to carry as a small portion of their course load, mostly required, writing intensive classes like Expository Writing and First Year Seminar. While I loved--truly loved--teaching those classes, helping non-writers tell their stories in engaging ways, the amount of grading made the course hours drift long beyond the time spent teaching and prepping. There are a variety of strategies professors use to get around reading tons of papers, including peer review and bookend grading (reading just the introduction and conclusion of a work) but this was not the culture of Pacific. Nor is it a personal characteristic. I care about my students too much to not read their work.By the time I left teaching I was burnt out and disheartened. Self-employment was hard, too, but once I found my niche (community teaching, go figure) after years of various endeavors (ceremonial celebrant, spiritual business consultant), I could craft a schedule supportive of my fatigue and mostly avoid the worst crashing. It's called coping, and it is a good strategy. But I didn't know what I was coping with just yet. So when I took on graduate school, ok, that was a lot to bring in to an already full life, I started having unusual symptoms. By the time I was dreaming at my parent's house in March of 2016, I had uterine fibroids, a cyst on my liver, a cyst on my ovary and a sinking sense that something was pretty wrong in my physical body. In the dream I received the job offer from Pacific, and I was joyful. But then I looked at the dream's version of my schedule. It was ALL writing intensive courses. The spirits said, no way, and I said, oh well, it was worth looking at. But I knew in the dream it would be a bad idea to take on such a schedule. I knew.When I woke up, I had an email with a job offer from Pacific and a schedule JUST like the one in my dream. Can you guess what I did?***I took the job. I became very sick. I still haven't recovered, almost a year later.***Spirit came to me in a dream this summer, on the full moon of August. A woman insisted that I teach a class in Ancestral Connection, a topic close to my heart and a big part of my own spiritual path. I told her I don't teach anymore. She would not let it go. Finally I said I would teach it, and with the pull of spirit led timing, was told it needed to begin on the first of November and proceed for four Wednesdays. When I woke up I checked the calendar. November 1 is on a Wednesday. Okay.I could choose to not listen. I'm in another big transition right now. We are moving out of the city, where I've lived for the past decade, where my husband works, where two of my children go to school. We are moving in large part because I can't work consistently, I still haven't improved in the way we've hoped and we are having to accept that dealing with my ME/CFS might be a long process. We can't afford to live here on one income. We could barely afford it on two. The move is daunting, my energy low. To live with spirit is to listen. I am a dreamer, I receive information in my dreams. Not just symbolic illusion, but clear communication. It is a pathway for my ancestors--one of many. The woman in my dream demanded I teach, never mind I've given it up, never mind the timing. If I follow, the wyrd weaves pattern. If I resist, it knots and twists, new paths emerge. Some take me to the same place, the hard way.Ancestral Connectionis offered by donation with a suggested contribution of $100 to help my family transition into our new living situation. Support your local wyrd sister. Lean on in, let's listen together.By this and every effort may the balance be regained.

Published on September 11, 2017 14:40

August 19, 2017

Resources for Resilience

These are some of the resources that have helped me understand the context and complexities of racism, allyship and the universal need for identifying and transforming systems of oppression. I come to these resources as a woman living in America of (presumed) European descent who is racialized as white. I am also the mother of multiracial children who are often—but not always--racialized as white. I am learning, it is a slow process, my education incomplete. But the journey of this education is what I wish to share, because dismantling the destructive paradigms that perpetuate racist, sexist, speciesist, homophobic ideologies requires solidarity on the path. I am indebted to my Building Conscious Allyship class at CIIS for many of these resources.You might wonder first at my use of the term "racialized as white," rather than calling myself a "white woman." Racilization is an active word that gives context to what happens to all of us, regardless of our ethnic or cultural backgrounds, in a race focused society. Race is one of those maddening points of simultaneity, as most social scientists agree that there is no genetic basis for racial separation, we are as a collective society racially mixed, and therefore racial categorization is something that happens based on perception. Yet, in spite of the illusion of race, racial discrimination is very real, and the formations of race occur regardless of the non-reality of racial purity. Thus racialization is something that happens to all of us, and while as a person who is racialized as white it is important to acknowledge the special treatment this racialization offers, it is equally important to recognize the universality of racialization and that it is an active principle, thus subject to change. Identity, therefore, can be transformed by simultaneously holding race as unreal, and understanding racialization.The creation of whiteness and other race categories occurred to protect and preserve the power of a particular racist perception, one intimately linked with capitalist goals, but not all people who would now be racialized as white were seen as deserving of the benefits and privileges of whiteness. The complex history around the creation of whiteness and other race categories is interwoven with the advent of "modern" slavery systems, the privatization of land, the genocide of women during the witch hunts, the destruction of non-Christian indigenous spiritual traditions—including those in Europe—and the colonization of continents. Understanding this history can help us see how we are all oppressed by the systems that perpetuate racism, (let's name some: Patriarchy, White Supremacy, Capitalism, Religion) and work together to create new systems to live by.Resources:On RacializationEveryone is Racialized from the University of Calgary:“The term ‘racialization' is very helpful in understanding how the history of the idea of ‘race' is still with us, impacts us all, profoundly, though differentially, as well, especially as the term emphasizes the ideological and systemic, often unconscious processes at work. It also emphasizes how racial categories are "constructed", including whiteness, but socially and culturally very real.Racialization is the very complex and contradictory process through which groups come to be designated as being of a particular "race" and on that basis subjected to differential and/or unequal treatment. While white people are also racialized, this process is often rendered invisible or normative to those designated as white, and as such, white people may not see themselves as part of a ‘race' but still as having the authority to name and racialize ‘others'. The process by which people are identified by racial characteristics is a social and cultural process, as well as an individual one. That is, a social order might "racialize" a group through media coverage, political action, and the production of a general consensus in the public about that group. An individual might "racialize" another individual or group by particular actions (e.g., avoiding eye contact, crossing the street, asking invasive questions) that designated the target individual or group as "other" or "not-normal." Racialization is a fluid process. A particular community might be "racialized" at a point in history but then later "pass into" whiteness (e.g. Italian Canadians). Whiteness and Whites can also be racialized but this process must incorporate anti-racist and alliance principles so that whiteness is perceived as a power-base, not a target."The Process of Racialization: From the University of York:“MANY SOCIOLOGISTS PREFER TO USE THE TERM RACIALIZATION AS OPPOSED TO RACE IN ORDER TO EMPHASIZE THE FACT THAT RACIAL CATEGORIES ARE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONS THAT CHANGE IN TIME AND SPACE AND CIRCUMFERENCE, AND ARE ATTRIBUTED WITH STATUS AND MEAN}”Aspiring Social Justice Ally Identity Developmentby Keith Edwards: Really useful in understanding the progression of ally psychology. I used this in comprehending my own identity progression with regard to spiritual artistic appropriation. See this blog post.The Problem With PrivilegeAndrea Smith:Speaking privilege is not enough.“Consequently, the goal became not to actually end oppression but to be as oppressed as possible. These rituals often substituted confession for political movement-building. And despite the cultural capital that was, at least temporarily, bestowed to those who seemed to be the most oppressed, these rituals ultimately reinstantiated the white majority subject as the subject capable of self-reflexivity and the colonized/racialized subject as the occasion for self-reflexivity.”Healing from Whiteness BlogSpecifically I found useful:How do I claim my own indigenous humanity as a white person?Cultural Amnesia: How the Celts Became WhiteWhat exactly is cultural appropriation and why is it harmful? (video)Marina Watanabe helps define cultural appropriation with regard to capitalist exploitation and spiritual symbolism. A worthwhile watchCaliban and the Witch by Silvia Federici (links to pdf of book, but you can also find it for sale)The history of the body in the transition to capitalism. As a woman of European descent this book helped me understand the history of the witch burnings, my ancestral patterns of fear, and the connection with racism, capitalism and Christian privilege. The Uses of AngerAudre Lorde“I have no creative use for guilt, yours or my own.”Coalition Politics by Bernice Johnson Reagon Johnson“We’ve pretty much come to the end of a time when you can have a space that is “yours only”—just for the people you want to be there.”Letter from Birmingham Jailby Martin Luther King, Jr.“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”Books that illustrate new stories, new systems, political, spiritual, personal:Woman on the Edge of Timeby Marge PiercyThe Fifth Sacred Thingby StarhawkLast thoughts:I find sheet mulching to be particularly cathartic. As someone with a disability that prevents much physical action, I can write and speak and turn my attention to making wild gardens, full of metaphor, newsprint dissolving in the bodies of worms, roots weaving through the baselessness of this time that is no time. Grow, seeds of new culture, seeds of the ancient. Chant with me: Grow grow grow grow grow.

These are some of the resources that have helped me understand the context and complexities of racism, allyship and the universal need for identifying and transforming systems of oppression. I come to these resources as a woman living in America of (presumed) European descent who is racialized as white. I am also the mother of multiracial children who are often—but not always--racialized as white. I am learning, it is a slow process, my education incomplete. But the journey of this education is what I wish to share, because dismantling the destructive paradigms that perpetuate racist, sexist, speciesist, homophobic ideologies requires solidarity on the path. I am indebted to my Building Conscious Allyship class at CIIS for many of these resources.You might wonder first at my use of the term "racialized as white," rather than calling myself a "white woman." Racilization is an active word that gives context to what happens to all of us, regardless of our ethnic or cultural backgrounds, in a race focused society. Race is one of those maddening points of simultaneity, as most social scientists agree that there is no genetic basis for racial separation, we are as a collective society racially mixed, and therefore racial categorization is something that happens based on perception. Yet, in spite of the illusion of race, racial discrimination is very real, and the formations of race occur regardless of the non-reality of racial purity. Thus racialization is something that happens to all of us, and while as a person who is racialized as white it is important to acknowledge the special treatment this racialization offers, it is equally important to recognize the universality of racialization and that it is an active principle, thus subject to change. Identity, therefore, can be transformed by simultaneously holding race as unreal, and understanding racialization.The creation of whiteness and other race categories occurred to protect and preserve the power of a particular racist perception, one intimately linked with capitalist goals, but not all people who would now be racialized as white were seen as deserving of the benefits and privileges of whiteness. The complex history around the creation of whiteness and other race categories is interwoven with the advent of "modern" slavery systems, the privatization of land, the genocide of women during the witch hunts, the destruction of non-Christian indigenous spiritual traditions—including those in Europe—and the colonization of continents. Understanding this history can help us see how we are all oppressed by the systems that perpetuate racism, (let's name some: Patriarchy, White Supremacy, Capitalism, Religion) and work together to create new systems to live by.Resources:On RacializationEveryone is Racialized from the University of Calgary:“The term ‘racialization' is very helpful in understanding how the history of the idea of ‘race' is still with us, impacts us all, profoundly, though differentially, as well, especially as the term emphasizes the ideological and systemic, often unconscious processes at work. It also emphasizes how racial categories are "constructed", including whiteness, but socially and culturally very real.Racialization is the very complex and contradictory process through which groups come to be designated as being of a particular "race" and on that basis subjected to differential and/or unequal treatment. While white people are also racialized, this process is often rendered invisible or normative to those designated as white, and as such, white people may not see themselves as part of a ‘race' but still as having the authority to name and racialize ‘others'. The process by which people are identified by racial characteristics is a social and cultural process, as well as an individual one. That is, a social order might "racialize" a group through media coverage, political action, and the production of a general consensus in the public about that group. An individual might "racialize" another individual or group by particular actions (e.g., avoiding eye contact, crossing the street, asking invasive questions) that designated the target individual or group as "other" or "not-normal." Racialization is a fluid process. A particular community might be "racialized" at a point in history but then later "pass into" whiteness (e.g. Italian Canadians). Whiteness and Whites can also be racialized but this process must incorporate anti-racist and alliance principles so that whiteness is perceived as a power-base, not a target."The Process of Racialization: From the University of York:“MANY SOCIOLOGISTS PREFER TO USE THE TERM RACIALIZATION AS OPPOSED TO RACE IN ORDER TO EMPHASIZE THE FACT THAT RACIAL CATEGORIES ARE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONS THAT CHANGE IN TIME AND SPACE AND CIRCUMFERENCE, AND ARE ATTRIBUTED WITH STATUS AND MEAN}”Aspiring Social Justice Ally Identity Developmentby Keith Edwards: Really useful in understanding the progression of ally psychology. I used this in comprehending my own identity progression with regard to spiritual artistic appropriation. See this blog post.The Problem With PrivilegeAndrea Smith:Speaking privilege is not enough.“Consequently, the goal became not to actually end oppression but to be as oppressed as possible. These rituals often substituted confession for political movement-building. And despite the cultural capital that was, at least temporarily, bestowed to those who seemed to be the most oppressed, these rituals ultimately reinstantiated the white majority subject as the subject capable of self-reflexivity and the colonized/racialized subject as the occasion for self-reflexivity.”Healing from Whiteness BlogSpecifically I found useful:How do I claim my own indigenous humanity as a white person?Cultural Amnesia: How the Celts Became WhiteWhat exactly is cultural appropriation and why is it harmful? (video)Marina Watanabe helps define cultural appropriation with regard to capitalist exploitation and spiritual symbolism. A worthwhile watchCaliban and the Witch by Silvia Federici (links to pdf of book, but you can also find it for sale)The history of the body in the transition to capitalism. As a woman of European descent this book helped me understand the history of the witch burnings, my ancestral patterns of fear, and the connection with racism, capitalism and Christian privilege. The Uses of AngerAudre Lorde“I have no creative use for guilt, yours or my own.”Coalition Politics by Bernice Johnson Reagon Johnson“We’ve pretty much come to the end of a time when you can have a space that is “yours only”—just for the people you want to be there.”Letter from Birmingham Jailby Martin Luther King, Jr.“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”Books that illustrate new stories, new systems, political, spiritual, personal:Woman on the Edge of Timeby Marge PiercyThe Fifth Sacred Thingby StarhawkLast thoughts:I find sheet mulching to be particularly cathartic. As someone with a disability that prevents much physical action, I can write and speak and turn my attention to making wild gardens, full of metaphor, newsprint dissolving in the bodies of worms, roots weaving through the baselessness of this time that is no time. Grow, seeds of new culture, seeds of the ancient. Chant with me: Grow grow grow grow grow.

Published on August 19, 2017 11:02

July 21, 2017

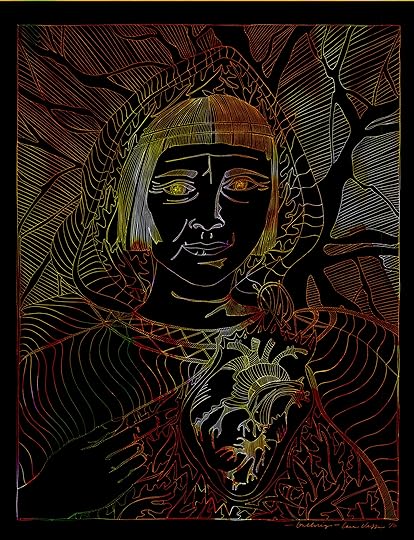

Connecting With the Ancestors

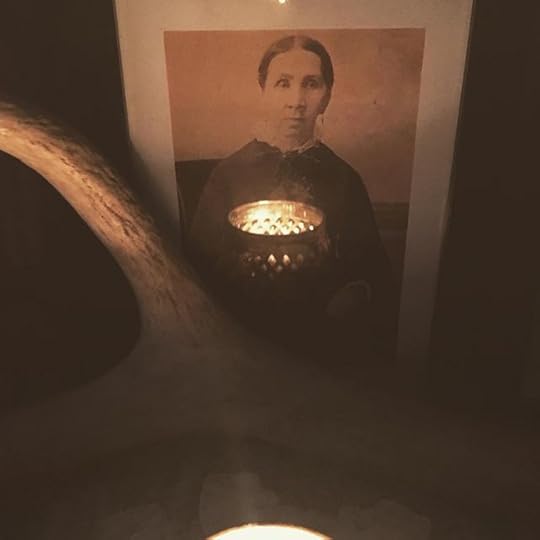

Our ancestors are hungry. In modern culture they are longed for but forgotten, or avoided, no longer the intermediaries between human life and divinity. This past week I wrote about ancestral connection, something I began four years ago and a path I continue daily to surprise, amazement and empowerment. I received many comments about yearning for ancestral connection, wondering how to build relationship with ancestors absent, or when the only known ancestry--family history--is painful and harmful. What follows is the beginning of my discovery, source and resource, on this journey. There is too much for one post, but here are some introductory ideas on how to work with your ancestors.First, some perspective. We all have millions of ancestors. The math is complicated by concepts like pedigree collapse and bottleneck situations (major death events like the plague) but on a theoretical level, everyone alive today is related to almost everyone else going back to about 8,000 BCE. So there are a lot of people to work with in our bloodlines. We tend to think of ancestors as those we know, and so if our immediate family is absent, messed up or unavailable, there can be a reluctance to pursue ancestral work. But ancestry is spirit work. You carry within you the genetic code of many. The patterns of people who performed atrocities, yes, they are in there. But also you contain those who perfomed magic. Healing. Nourishment. Who made beauty. Who await your attention.Ancestor work is especially important now for a number of reasons. The primary one is that we are so distant from living close to the earth and the beings of nature. Who better to teach us about place based, earth centered living than relatives who lived this way for thousands of years? We all have people of the earth in our lineages. Each one of us. Some of us come from traditions that are buried and deeply fragmented, but dreaming and walking with our ancestors can help unearth the wisdom inherent in our bones.I should also state here that I'm not an expert, I'm a seeker on a particular path. I practice the religious traditions of my ancestors from Northern Europe and so much of my work is focused on those spiritual methodologies. I do include information from my time in the Women's Spirituality program at CIIS, and welcome insights from those practicing in other traditions. My children are multiracial, and one of the reasons I began this path was so that they could have a rich, complete spiritual identity. As a woman racialized as white, it has been revolutionary to explore my ancestors and offer to my children a fuller understanding of their European lineage. It also has led me away from spiritual appropriation. What I seek is available in my lineage history if I'm willing to dig deep and confront my fears.This work may bring up a lot of fear. We have been conditioned to look outside ourselves for spiritual information. Not only this, but many women of European descent carry deep trauma from the witch hunts, a kind of ancestral obliteration where we had to hide our relationships with the spiritual and magical. Many of the indigenous spiritual traditions in Europe were intentionally dismantled first by church policy, then by political violence. (Huge intersectionality here with the witch hunts, the advent of capitalism, the colonization of the Americas and the beginning of the global slave trade--there is a root of widespread oppression in this time. See the book Caliban and the Witch by Sylvia Federici for more about this complex of shared history.) It was not that long ago in blood time. I find that whole swaths of information in my family line are obscured from me in ritual or meditation, and so the work of claiming is about persistence.First Steps for Ancestral ConnectionGather as much information as you can about all of your ancestors, including those you may know such as parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles. Start assembling family stories, anecdotes, photos, documents. Look at where you have resistance or wish to simplify matters. I have a friend with a powerful paternal Hispanic presence in her family, who had never explored her mother's Scottish roots because she saw them as less interesting. When she began to investigate her resistance she found an intense connection with the magical practices of Scotland, and was able to uncover the synergy between her paternal and maternal lineages. Resistance can often mean the presence of power, and complexity is strength. We are made of multitudes, you don't have to choose or preference one, and often different ancestries will call to you at different times.If you have little or no information about your ancestors, don't despair. They are already in you. You can access your ancestors at any time. A lack of information does not mean a lack of connection. You don't need anything except intuition and will to connect with your ancestors. Tools for CommunicationAncestor Altars: Gateway to the Bloodline Crafting an altar for the ancestors in your home is most effective when you are clear on your intention. Is it to heal bloodline trauma? To create new connections? To discover their spiritual practices? Once you know the purpose of your altar, allow yourself to be led to the colors and textures that reflect your purpose (once you have a relationship with the ancestors they will let you know intuitively what they do and don't prefer). You may choose to add photos of your actual ancestors, images of places they came from, objects that belonged to your family, or symbolic art representing your intention. Then make offerings. Traditional offerings to the ancestors include food, beverages, fresh flowers, herbs and stones. Tend the altar with a daily ritual practice. It doesn't need to be big, five or ten minutes of attention is enough to begin some energetic collaboration. (For more information on ritual practice, see the 13 Days of Ritual in the Wild Soul School.)Dining With the AncestorsA simple way to let your ancestors know you are thinking of them is to set a place at the table and ritually feed them with your family. This can be done in a quiet, informal way, or in a more formal ritual where you call in your ancestors to eat with you. Make a plate of food for the ancestors. Once you complete the meal, you may place the food on your altar, removing it the following morning or when the meal feels done.Sharing Drinks With the AncestorsToasting the ancestors with your beverage of choice (preferably something delicious) then pouring out some of the liquid onto the earth in their honor is a traditional way of making offering and including the ancestors in your daily life. This may be done with regularity. If indoors, you can simply pour a cup for your ancestors, toast them, and leave it on your altar. Thanking the AncestorsThey are the reason we all exist. Those millions of lives cycled through time so that you could be born at this particular place, with this unique set of characteristics and circumstances. If you have children, the potentiate of the ancestors is even more vital: they live through you and into your offspring. In my spiritual tradition the female ancestors are called the Disír, and have a vested interest in aiding the perpetuation of the lineage. Thanking the Disír, thanking all of the ancestors for the gifts you've received, for the safe passage of a child into this world, or for future protection, is a powerful practice. Dedicating your work in this life to the ancestors and descendants helps orient your offerings in the scope of spirit time. Daily Power Practice--Ancestor WorkAttune to ancestral wisdom by opening and closing each day with them in intention. MorningIn the morning, as part of a ritual practice, ask your ancestors:What would you wish of me today?See what comes forward. This might be a meditation, a journaling exercise or an art practice. Keep a record of your process. The instructions of the ancestors might be obscure at first, but after a while they will become more clear.EveningAs you go to bed at night, imagine yourself in a circle of protection. From this place, set an intention to dream with your ancestors. Ask for guidance on any issue, or for further relationship. In the morning, write down any images or symbolic information. And give thanks.In the next few weeks I'll offer several posts with more information on specific ancestral connection, including my own journey and a ritual meditation that I've used in The Power Class with incredible results. Most ancestor work must come from your own direct experience. With this in mind, I offer some reading with a caveat: you won't ever find without what is already available within. No one can communicate with your ancestors like you. Because they are yours. Alu.A few books I've found helpful on my path:Ancestor Reverence essay by Luisah Teish in Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Women's SpiritualityThe Well of Remembrance: Rediscovering the Earth Wisdom Myths of Northern Europe by Ralph MetznerWitches and Pagans by Max DashuThe Black World chapter in Neolithic Shamanism by Raven KalderaThe Motherline by Naomi Ruth LowinskyMay this work reach those who need it. May the balance be regained.http://www.genetic-genealogy.co.uk/supp/ancestor_paradox.html

Our ancestors are hungry. In modern culture they are longed for but forgotten, or avoided, no longer the intermediaries between human life and divinity. This past week I wrote about ancestral connection, something I began four years ago and a path I continue daily to surprise, amazement and empowerment. I received many comments about yearning for ancestral connection, wondering how to build relationship with ancestors absent, or when the only known ancestry--family history--is painful and harmful. What follows is the beginning of my discovery, source and resource, on this journey. There is too much for one post, but here are some introductory ideas on how to work with your ancestors.First, some perspective. We all have millions of ancestors. The math is complicated by concepts like pedigree collapse and bottleneck situations (major death events like the plague) but on a theoretical level, everyone alive today is related to almost everyone else going back to about 8,000 BCE. So there are a lot of people to work with in our bloodlines. We tend to think of ancestors as those we know, and so if our immediate family is absent, messed up or unavailable, there can be a reluctance to pursue ancestral work. But ancestry is spirit work. You carry within you the genetic code of many. The patterns of people who performed atrocities, yes, they are in there. But also you contain those who perfomed magic. Healing. Nourishment. Who made beauty. Who await your attention.Ancestor work is especially important now for a number of reasons. The primary one is that we are so distant from living close to the earth and the beings of nature. Who better to teach us about place based, earth centered living than relatives who lived this way for thousands of years? We all have people of the earth in our lineages. Each one of us. Some of us come from traditions that are buried and deeply fragmented, but dreaming and walking with our ancestors can help unearth the wisdom inherent in our bones.I should also state here that I'm not an expert, I'm a seeker on a particular path. I practice the religious traditions of my ancestors from Northern Europe and so much of my work is focused on those spiritual methodologies. I do include information from my time in the Women's Spirituality program at CIIS, and welcome insights from those practicing in other traditions. My children are multiracial, and one of the reasons I began this path was so that they could have a rich, complete spiritual identity. As a woman racialized as white, it has been revolutionary to explore my ancestors and offer to my children a fuller understanding of their European lineage. It also has led me away from spiritual appropriation. What I seek is available in my lineage history if I'm willing to dig deep and confront my fears.This work may bring up a lot of fear. We have been conditioned to look outside ourselves for spiritual information. Not only this, but many women of European descent carry deep trauma from the witch hunts, a kind of ancestral obliteration where we had to hide our relationships with the spiritual and magical. Many of the indigenous spiritual traditions in Europe were intentionally dismantled first by church policy, then by political violence. (Huge intersectionality here with the witch hunts, the advent of capitalism, the colonization of the Americas and the beginning of the global slave trade--there is a root of widespread oppression in this time. See the book Caliban and the Witch by Sylvia Federici for more about this complex of shared history.) It was not that long ago in blood time. I find that whole swaths of information in my family line are obscured from me in ritual or meditation, and so the work of claiming is about persistence.First Steps for Ancestral ConnectionGather as much information as you can about all of your ancestors, including those you may know such as parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles. Start assembling family stories, anecdotes, photos, documents. Look at where you have resistance or wish to simplify matters. I have a friend with a powerful paternal Hispanic presence in her family, who had never explored her mother's Scottish roots because she saw them as less interesting. When she began to investigate her resistance she found an intense connection with the magical practices of Scotland, and was able to uncover the synergy between her paternal and maternal lineages. Resistance can often mean the presence of power, and complexity is strength. We are made of multitudes, you don't have to choose or preference one, and often different ancestries will call to you at different times.If you have little or no information about your ancestors, don't despair. They are already in you. You can access your ancestors at any time. A lack of information does not mean a lack of connection. You don't need anything except intuition and will to connect with your ancestors. Tools for CommunicationAncestor Altars: Gateway to the Bloodline Crafting an altar for the ancestors in your home is most effective when you are clear on your intention. Is it to heal bloodline trauma? To create new connections? To discover their spiritual practices? Once you know the purpose of your altar, allow yourself to be led to the colors and textures that reflect your purpose (once you have a relationship with the ancestors they will let you know intuitively what they do and don't prefer). You may choose to add photos of your actual ancestors, images of places they came from, objects that belonged to your family, or symbolic art representing your intention. Then make offerings. Traditional offerings to the ancestors include food, beverages, fresh flowers, herbs and stones. Tend the altar with a daily ritual practice. It doesn't need to be big, five or ten minutes of attention is enough to begin some energetic collaboration. (For more information on ritual practice, see the 13 Days of Ritual in the Wild Soul School.)Dining With the AncestorsA simple way to let your ancestors know you are thinking of them is to set a place at the table and ritually feed them with your family. This can be done in a quiet, informal way, or in a more formal ritual where you call in your ancestors to eat with you. Make a plate of food for the ancestors. Once you complete the meal, you may place the food on your altar, removing it the following morning or when the meal feels done.Sharing Drinks With the AncestorsToasting the ancestors with your beverage of choice (preferably something delicious) then pouring out some of the liquid onto the earth in their honor is a traditional way of making offering and including the ancestors in your daily life. This may be done with regularity. If indoors, you can simply pour a cup for your ancestors, toast them, and leave it on your altar. Thanking the AncestorsThey are the reason we all exist. Those millions of lives cycled through time so that you could be born at this particular place, with this unique set of characteristics and circumstances. If you have children, the potentiate of the ancestors is even more vital: they live through you and into your offspring. In my spiritual tradition the female ancestors are called the Disír, and have a vested interest in aiding the perpetuation of the lineage. Thanking the Disír, thanking all of the ancestors for the gifts you've received, for the safe passage of a child into this world, or for future protection, is a powerful practice. Dedicating your work in this life to the ancestors and descendants helps orient your offerings in the scope of spirit time. Daily Power Practice--Ancestor WorkAttune to ancestral wisdom by opening and closing each day with them in intention. MorningIn the morning, as part of a ritual practice, ask your ancestors:What would you wish of me today?See what comes forward. This might be a meditation, a journaling exercise or an art practice. Keep a record of your process. The instructions of the ancestors might be obscure at first, but after a while they will become more clear.EveningAs you go to bed at night, imagine yourself in a circle of protection. From this place, set an intention to dream with your ancestors. Ask for guidance on any issue, or for further relationship. In the morning, write down any images or symbolic information. And give thanks.In the next few weeks I'll offer several posts with more information on specific ancestral connection, including my own journey and a ritual meditation that I've used in The Power Class with incredible results. Most ancestor work must come from your own direct experience. With this in mind, I offer some reading with a caveat: you won't ever find without what is already available within. No one can communicate with your ancestors like you. Because they are yours. Alu.A few books I've found helpful on my path:Ancestor Reverence essay by Luisah Teish in Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Women's SpiritualityThe Well of Remembrance: Rediscovering the Earth Wisdom Myths of Northern Europe by Ralph MetznerWitches and Pagans by Max DashuThe Black World chapter in Neolithic Shamanism by Raven KalderaThe Motherline by Naomi Ruth LowinskyMay this work reach those who need it. May the balance be regained.http://www.genetic-genealogy.co.uk/supp/ancestor_paradox.html

Published on July 21, 2017 09:53

July 14, 2017

The Work of Self-Love

Transition is life work. Every day is a cycle of transition. Every change a moment of transformation. Right now I am in transition, a myth cycle like Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey or Maureen Murdoch's Heroine's Path. Transition is multiple and mutable, it happens in the micro and macro levels. Sometimes the road of trials is predictable and smooth. Other times, we get caught in the unexpected, the extraordinary. Even the good things in our lives--births, partnerings, new endeavors--can carry the weight of passage. Death is present in every change and however welcome, honoring the past, the lost, bringing into integrity the grief, the truth, this is the work of living fully. :: Ritual helps navigate transition. Even small rituals create psychic trails in the wilderness of our lives. An ancestral familiarity is opened as we connect with forces beyond the moment, our blood wisdom, our sacred craft. Rituals move us through the known and the unknown with greater ease. Ronald Grimes writes in Deeply Into the Bone that missed rites of passage leave holes in us, that we are haunted as by ghosts when we don't honor our transitions. :: This can feel daunting. So many unmarked passages accumulate in our lives, how can we possibly come into integrity with every transition? We can't. But we can begin to practice effective rituals daily, to build in the rooting and honoring of transition through self-care and story shaping. Tiny though they are, daily ritual practices open the door for a powerful wholeness. :: In 13 Days: A Ritual Practice we are going to create and sustain these daily anchor rituals for 13 days, beginning August 2nd, traveling through the full August moon and resting at the waning half moon in Taurus on August 14th. If you haven't already, register for the free practice at The Wild Soul School. I will be sending out more information about additional resources via the Wild Soul School early next week. :: Photo by the amazing @lorijo45

Transition is life work. Every day is a cycle of transition. Every change a moment of transformation. Right now I am in transition, a myth cycle like Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey or Maureen Murdoch's Heroine's Path. Transition is multiple and mutable, it happens in the micro and macro levels. Sometimes the road of trials is predictable and smooth. Other times, we get caught in the unexpected, the extraordinary. Even the good things in our lives--births, partnerings, new endeavors--can carry the weight of passage. Death is present in every change and however welcome, honoring the past, the lost, bringing into integrity the grief, the truth, this is the work of living fully. :: Ritual helps navigate transition. Even small rituals create psychic trails in the wilderness of our lives. An ancestral familiarity is opened as we connect with forces beyond the moment, our blood wisdom, our sacred craft. Rituals move us through the known and the unknown with greater ease. Ronald Grimes writes in Deeply Into the Bone that missed rites of passage leave holes in us, that we are haunted as by ghosts when we don't honor our transitions. :: This can feel daunting. So many unmarked passages accumulate in our lives, how can we possibly come into integrity with every transition? We can't. But we can begin to practice effective rituals daily, to build in the rooting and honoring of transition through self-care and story shaping. Tiny though they are, daily ritual practices open the door for a powerful wholeness. :: In 13 Days: A Ritual Practice we are going to create and sustain these daily anchor rituals for 13 days, beginning August 2nd, traveling through the full August moon and resting at the waning half moon in Taurus on August 14th. If you haven't already, register for the free practice at The Wild Soul School. I will be sending out more information about additional resources via the Wild Soul School early next week. :: Photo by the amazing @lorijo45

Published on July 14, 2017 12:35

June 27, 2017

A Prayer for My Untended Dead

It is hard to focus when there is a ghost in your office, especially a spirit as cannily gorgeous and witty as the late Dr. Lorelle Browning. I heard her coming down the hall, sparks of light gleaming from her layers of jewelry, a delicious laugh and fragrance marking the space-time continuum. It would be impossible not to welcome her in. Here she is now, standing in the corner, waiting for me to say something real. Lorelle died of cancer, the first of three women in my life to succumb in a short six months. When she died I hadn’t seen her for years. Our last day together in 2012 was a spring one, chill and rain. I had just finished packing my belongings and was preparing to leave Pacific University, where I received my MFA, where I taught as a professor of writing for five years. Lorelle was department chair and took me to lunch as a gesture of farewell. Halfway through a Caesar—lemony, herbed--she grabbed my hand, “I’m going to get you back here,” she said, squeezing with determination. Faith in her undeniable power.And, she did. The Norse had a word for ancestral spirits, community guardians, their beloved dead: Dísir. The Dísr could be single (Dís) or collective, would appear to tell the fates of children at birth--good fairies around Sleeping Beauty’s cradle--and just as easily the Dísir could cast lots determining who should die. Dísir were specifically female, powerful, respected and feared. They had a vested interest in the continuation of their lineage so would let you know if you were making errors in judgment. The Dísir’s curse—discomfort for the recipient in this lifetime--could be curative, collective, a balm for future generations. There were feast days for the Dísir, lengthy celebrations of ceremony, offerings and theatre. Reverence of the dead extends cross cultures, with elaborate rituals including the exhuming of the bones, preservation of the corpse, ancestor honoring celebrations such as Dia De Los Muertos. Yet in America our experiences of and with death are alarmingly blunt. Our beloveds die, we grieve for a proscribed period of time (the average paid leave is three days), and return to life as normal. Our public shrines include the usual places of worship, roadside crosses and the occasional spontaneous memorial. Our mourning is private, and its expression brief. I learned of Lorelle Browning by reputation. My former husband was a student of hers in the 1990’s. A business major and self-described non-reader, English classes terrified him. He said Lorelle swept in on the first day of class quoting Shakespeare and standing on desks for oration. He had never experienced a teacher so passionate about her chosen field, and she shocked him into reading, studying and investigating language as art. She opened his mind, and in this way I can thank her for that early relationship, for my two children. If my former husband hadn’t met Lorelle and started reading I’m pretty sure we would never have married at all. Like many Americans I am the child of immigrants. My people come from Norway, Sweden, Ireland, England, Scotland, Germany and Czechoslovakia. The earliest traversed the Atlantic in the 1600’s. The most recent, my maternal grandfather, Sigurd Rosenlund, came to the US from post-war Norway in the 1950’s to attend college at UC Berkeley. With this varied background we don’t have any set rituals around our dead. Some of us are religious. My cousin is an evangelical minister. My paternal grandparents were both raised Catholic but later left the church after the Paso Robles parish priest refused to bury my devout Czech great-grandmother, Mary Uchitel, in the sanctified churchyard soil. They couldn’t find her birth certificate, or proof of baptism, so in death she was never Catholic at all. My beloved dead are burned or buried quickly and with little ceremony. Tucked away in corners of cemeteries in California and Oregon, scattered on the waves of the Pacific Ocean and the Bergen fjord. They are not forgotten but spread out so we miss them but do not visit them. We miss them and move on. The rest of my American-dead ancestors rest in piecemeal places: Kentucky, New Jersey, New Hampshire, the Dakotas, Washington State. Lately I have begun to trace them, following a path of irregular lines and incomplete records. Genealogy is elitist. There are vast resources devoted to my educated, professional ancestors, like Isaac Huntoon, founder of Anacortes, Washington. Disappeared are the migrant workers, the illiterate and those fleeing oppression from Russia or famine from Ireland. Learning their stories, I try to gather up their bones, to bring them into some unknown, unlived in, home. In my heart, my mind, my memory I reconstitute an imaginary geography, a resting place for the untended dead. I told Lorelle about my former husband one day, standing on the graves of pioneers before Marsh Hall on the Pacific campus. I had only been there for a few weeks, starting as a teaching associate after receiving my MFA a few months before. I didn’t know then that teaching had been hard for Lorelle after an early stroke, or that she was still recovering her physical capacity. But in that moment we exchanged something more pertinent than information—a tracing of vulnerability and mutual admiration that leads to the connection of friends. I was raw that year. I grew up in southern Oregon and my education has always felt inadequate compared to my colleagues with their R1 degrees and research fellowships. I am a storyteller, an artist and writer who is missing whole chunks of early grammar and the literary canon. Thinking of myself as an academic would mean pretending I was one… exhausting. I’ll admit I laughed the first time someone called me Professor. In 2007, as a teaching associate with a degree in Fiction, I’d spent much of the past decade pregnant, nursing and tending my two children. I’d never taught a college class before, and though I knew a few faculty who were mothers, there were no other single moms in sight—which makes sense given that the university didn’t (still doesn’t) have child care. I felt new and dumb, scared and alone. Lorelle didn’t have children. In the eulogy, delivered by her charismatic brother, I learned more about her than I had known in life. The truth is we were not close. I had never met her husband or visited her home. We didn’t socialize off campus. She was a mentor more than a friend. Luisia Teish says that to honor the dead you should cover a table or altar in white cloth, and place a clear glass of water with a teaspoon of strong spirits in it. Raven Kaldera says that ancestors must be propitiated with regular offerings of food, dedications of music or flowers, and that once you start working with them you can’t stop without risking displeasure. My children’s father is Hispanic, and each year in our household we build an ancestor altar at the cross-quarter day between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice: the witch’s new year for my ancestors, Dia de Los Muertos for his. We leave it up for a few weeks, or a lunar cycle and make food for the dead: strong coffee for my grandpa Sigurd and great-grandma Louise, almond pastry for my grandma Barbara. Each morning before I write I light the candles on the altar and speak to the dead, to let them know I am listening. Albert Einstein said we could live as if everything was a miracle, or as if nothing was. And as I get older I feel the truth in these words. I could believe that the past is the past, over and done, that my ancestors and the dead I love have disappeared from this plane and will never return. This, to me, feels shortsighted and lacking context. When did we stop believing that those we love are with us? When did we stop bathing the bodies of our newly deceased, holding the traditional three day wakes while their souls left the earth, telling their stories, tending their graves, never leaving them in our lives alone? In January of 2012 I was walking through downtown Portland with my partner when Lorelle called in her official capacity asking about my teaching schedule for the next year. I told her I wouldn’t be returning. I’d finally received a diagnosis after years of exhaustion and illness amid unrelenting transition. I had a low-grade uterine infection, present for nearly twenty-four months. A double course of antibiotics set me on the road to healing but I was wiped out. Not just from the illness, but from the academic culture, the pressure to perform, the constant sense of inadequacy. In many cultures consumption of the dead is seen as literal. Our communities are buried in the ground, where we plant and gather food. We are not ever separate from the dead, there is a communion, life to life. We are not divided from the sacredness of dying, knowing we would be food for the future. Martín Prechtel in his book The Smell of Rain on Dust: Grief and Praise says, “When you have two centuries of people who have not properly grieved the things that they have lost, the grief shows up as ghosts that inhabit their grandchildren.” I feel the ghosts of my ancestors in me like strands of cat gut, strung tight over my synapses. They vibrate painfully in a longing for home, the desire to find a place of origin, to learn the language and songs, piece together a creative mythology that allows for a present past, a mythic present. I know that at middle age I am just beginning my losses. My grandmother, the youngest of twelve, lost both of her parents by the time she was twenty-five and all of her siblings by fifty. Each day, each year is a potential for more loss. And instead of clinging , I wish to be faith-full, full of ways to honor in each day the loved ones who are no longer flesh, crafting in community rituals that breathe the life of death into each cyclic year. My ancestors lost and lost: homes, lands, families, friends, languages, identities, religions. Their lives were journeys of displacement, generational dispossession: For Jane who arrived on the famine ships from Ireland, who lost her husband at sea and set sail again from New York to San Francisco with her infant daughter. For Irene whose mother died in childbirth along with her twin brother, whose father died soon after, who was sent to live with relatives in Kentucky, Chicago, New Jersey. For Frank whose parents claimed they were Catholic but may have been Jewish, fleeing from persecution in Russia to the tundra of Canada, then the harsh plains of the Dakotas, then to migrant work in almond orchards of California. For my grandfather, Sigurd, who left Norway at the end of World War II to get an education. The universities in Norway were decimated by the war, and receiving the news of acceptance to study chemistry in the United States felt like salvation to him. Boarding the ship to New York he didn’t realize he was saying goodbye to his homeland forever, for in the years of his absence he would meet my grandmother, marry and make the US his home. And in that first year away at school his mother would die. He wrote later, with pain that is tactile, even generations removed, about never seeing his mother again. This loss, this longing is twofold: we long for home, for place, for the landscape of knowing. We long for people, for the home of relationship we find within them. At the crux of these longings: connection, durability, eternity, remembrance. I dream of Lorelle. In the last, months ago, she smiled at me and tapped my shoulder with one bold and manicured nail. “You are an academic,” she said, her eyes sparking with what I miss most. Her intelligence. Her brain of fire. Or maybe I didn’t dream this, I can’t find it in any of my journals. But it is so vivid, this memory, her insistent touch. What we lose we make again, in memory and practice we invent new philosophies, legacies and lineage. Because if everything is a miracle, then the miraculous might bring us to what Edward P. Jones describes as, “seeing again for the first time.” Because of that dream that was perhaps not a dream, I applied and was accepted to the PhD in Philosophy and Religion program at CIIS in San Francisco. And because of this dream I accepted a position to teach again, this year, at Pacific University. Which is why I am squatting in this office with Lorelle in the corner. Where she wants me to tell you what I know. I know our dead are untended and they haunt us for it. We wonder when we will get over it, get past the suffering and struggle. We wonder when we will become ourselves again in the face of so much loss. Yet the duration of our grief is centuries long, existing beyond our lifetime. In Germany psychologists have begun vastly popular programs to treat unhealed ancestral grief, to repair rifts in the stories, to tend what was before unseen. Lorelle had just been awarded her second Fullbright fellowship when she was diagnosed with cancer. I don’t have all of the details, I wasn’t present at her end. I do know the reason that I wasn’t able to visit in her last months was because the university she had devoted her life to had a practice that would remove her from the payroll if she was unable to work. Removal from the payroll meant removal from health benefits. So her colleagues worked a necessary subterfuge to keep Lorelle working even as she died. Projects, projects for the dying. She is nodding now over me, and my skin is goosebumped, my throat tight. I come from a line of strong, courageous women, we all do, but we never get to say exactly how strong we really are. To speak it is a risk that once bore our deaths by burning or drowning, accusations of witchcraft. Now we risk our livelihoods, our futures by expressing what we bear. In secret we might whisper, how did you survive that pain? I told Lorelle about my uterine infection. And she shared that she had Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. We carried within us a similarity our exteriors did not show. To admit these things openly as academics carries stigma, and already in my semester this year I feel like I don’t want to rock the boat. In the past four years I have been self-employed, have moved twice, homeschooled my children. With this autumn I remember how much I love teaching, it makes me feel joyful, it expands my heart. A paycheck just made its way into my bank account and will appear again at the end of this month for the next eleven months. My current husband and I have a dual income and health insurance for the first time in our eight-year relationship. But as I write this I realize I can’t forgive a system that made it impossible for me to be a supported single mother and a professor, to work my way out of the poverty that early academic careers require. And I can’t forgive a system that would take a dying woman off of her insurance policy, that would force her disabled partner to bear not just his grief but outstanding debt. Lorelle, I see you and I remember.Lorelle, I see you and I won’t forget.Is this enough? Here in the late light of a September afternoon the ghost of my mentor, Dr. Lorelle Browning, nods her head and smiles, but mouths the word no. When my maternal grandmother Barbara died two years ago there was talk about a celebration of life. We had a small ceremonial acknowledgement, just my immediate family and my cousin, where we toasted and told Barbara’s stories and ate her famous fudge bar cake. But we have yet to all come together, her children and grandchildren, strung along the West coast, to scatter her ashes and memorialize her passage. At my graduate school residency last summer, I learned that I have deep roots on Barbara’s side in San Francisco. My grandmother’s father grew up on Iowa Street, the son of Jane, the Irish immigrant and her second husband John, also from Ireland. They lived in a house that was later demolished to make room for the 405. When I booked an Air B&B in the Mission District I found myself next door to St. Peter’s Cathedral. I felt something in the early morning air there, a dense familiarity as I walked through the district to school in SoMa each day. It wasn’t until later I learned that St. Peter’s was the Irish community center for that part of San Francisco. Jane, John, and their children, including my great-grandfather, walked the same streets to worship. We know more than we know. Somewhere in us the dead live, legions of them, in our blood and bones and cells. I love the studies on immunological memory, on genetic transference, proving that we do not just fade out from existence but persist, in our legacy, the bodies of our descendants, neighbors, colleagues and friends. The university bought a first folio page of Shakespeare’s –to honor Lorelle. It will be displayed as part of the permanent collection. I have a meeting this week with the university chaplain, to talk about creating non-religious spiritual programming for the students. Last fall I taught a class for a colleague where I had participants imagine the connection of their ancestors, as far back as they could go, roots of memory and heritage filled the earth below us humming with excitement and instruction. A student told me this week that she studied abroad in Ireland at the urging of her ancestors in that very class. A seed, blown, sometimes finds its way home. This year I call on my Dísir, my sacred female ancestors, to watch over me as I endeavor to remember my beloved dead. Toward this, Lorelle, a beginning propitiation.An imperfect action.With imperfect words.**I wrote this essay in the fall and became seriously ill in December of last year, so am currently not employed--at all, let alone by Pacific University--and am no longer a student at CIIS.