Gullveig/Hei∂ and the Birth of Witchcraft in the North

This is the full text of an essay I wrote for the CIIS Women's Spirituality PhD program in 2016. Health reasons have forced me to leave the program, but I am sharing some of the work I completed in the interest of opening. I would change some of this essay today, in light of new information from Max Dashú's Book Witches and Pagans, Women in European Folk Religion which covers Gullveig and the Völuspá in depth and was not published at the time of my writing. I also have found the work of Marija Gimbutas and Silvia Federici to be particularly helpful.  THRICE BURNED AND YET SHE LIVES: CLAIMING THE RUNIC FEMININENow she remembers the war,The first in the world,When GullveigWas studded with spears,And in the hall of the High OneShe was burned;Thrice burned,Thrice reborn,Often, many times,And yet she lives.She was called HeiðrWhen she came to a house,The witch who saw many things,She enchanted wands;She enchanted and divined what she could,In a trance she practiced seidrrr,And brought delightTo evil women.--The Poetic Edda, Völuspá[1]Forward This is not a paper. It is a story. And like all stories of mythic time, it has no beginning and no end. As usual, living in perceived non-mythic time, I worry about making the story right, about remembering all of the elements that I am “supposed” to incorporate. As a student new to the study of archaeomythology, I am confronted with a set of “working assumptions”[2] developed by Joan Marler based on the work of Marija Gimbutas. Each assumption could take me in a thousand different directions, and choosing to focus on the fragments and fractures of northern European spiritual symbols feels overwhelming even as I write these words. Marler defines Gimbutas’ archaeomythology as, A discipline that covers such vast territory is intimidating, for I feel I have barely begun over this semester to scratch the surface of interlocking layers, specifically with regard to my subject: the fractured esoteric and religious traditions of northern Europe, defined here as modern Scandinavia, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland and the British Isles.[3] Yet when I sink into the dream of my ancestors, the curators and creators of these ancient artifacts, the runes, whose histories I seek, they laugh at my right and wrong. They say, “There is no one way, there is only the way.” Therefore I ask to honor them, these ancient peoples, their memory, with this work. And I dedicate this writing to Gullveig, the thrice-burned Goddess whose transformative murder in the Poetic Edda attests to the magical power of women in prehistoric northern Europe. Explorations of Gullveig ‘s story illuminate my own standpoint as a feminist scholar and seeker of northern European spirituality. It is through personal relationship with the runes that I have come upon the thread of their origins. It is through speaking the story of Gullveig that still she lives. With permission from the ancestors I seek to narrow the scope of my viewing and look at Joan Marler’s four working assumptions of archaeomythology as detailed by Professor Mara Keller:1. Sacred cosmologies are central to the cultural fabric of all early societies.2. Beliefs and rituals expressing sacred worldviews are conservative and not easily changed.3. Many archaic cultural patterns have survived into the historical period as folk motifs and as mythic elements within oral, visual and ritual traditions.4. Symbols, preserved in cultural artifacts, “represent the grammar and syntax of a kind of meta-language by which an entire constellation of meanings is transmitted.”[4] For the purposes of this paper I will be focusing on the last two assumptions in my investigations: the surviving cultural patterns recorded in the historic Norse myths, and the symbols preserved in northern European archaeology and folklore. It is from this symbolic fabric that my own journey with the runes begins, and where intersections may be found beyond the datable artifacts of recorded history, into the dust-blurred realms of pre-history, where symbols correspond the deep cultures of Old Europe as defined by Marija Gimbutas.[5] Gimbutas looks to the Neolithic in her vast study of Old European civilization, focusing on, “the peoples who inhabited Europe from the 7th to the 3rd millennia BC…referring to Neolithic Europe before the Indo-Europeans.”[6] As I trace back through time before the Vikings, before the Eddas, the Christian transcribed myths of northern Europe written in 13th Century Iceland, before the rune stones, my intuition pricks and my ancestors follow chill fingers up my spine. There is something, here, waiting to be known. Or, as my teacher Ingrid says:“Before the Vikings, before the Christians, before Odin and Thor....the Runes were.”[7]From Whence, the Runes My mother has a pendant inscribed in runes from her father’s hometown of Bergen, Norway. On one side it bears an engraving of a spinning wheel, on the other mysterious writing that captivated me as a child. In early college I paid a student of languages to translate the pendant for me. It was written not in new Norwegian, but in Old Norse and read, “Lake, River, Mountain, Norway.” I thought the words lovely, if pedestrian. I didn’t know that each letter was a rune, each symbol more than a word, but rather a “secret or whispered mystery”[8]. It would be nearly two decades before the runes would come into my life as beings and creatures that sing songs and inform. Modern scholars have puzzled at the origins of the runes. There is a conflict in the interpretation of the runes, for they are seen as either a pragmatic alphabet or a magical, ritual tool.[9] Logical conclusions run that runes were both. Adrian Poruciuc writes, “Much of the mystery that surrounds runes is actually due to the failure of practically all attempts at establishing where, when and by whom runes were “invented.””[10] Amid such flummoxing resistance to a developmental timeline, archaeological evidence appears to be equally obscure. The generally accepted oldest datable (and translatable) runic inscription on an archaeological object is on the Vimose comb from 160 CE Denmark,[11] which appears to bear the name of the comber. And an earlier find, the Meldorf fibula, from 50 CE in North Germany, is possibly a runic inscription…or proto-runic…or Roman,[12] the arguments prevail in the absence of evidence. In looking for the origins of the runes, I turn then to mythology for a clue as to where to pick up a trail deep and historically cold. In the Hávamál, a poem from the Elder Poetic Edda recorded 13th Century CE Iceland, the runes are attributed to a “taking” by the god Odin after sacrifice:I know that I hungOn the wind-blasted treeAll of nights nine,Pierced by my spearAnd given to Odin,Myself sacrificed to myselfOn that poleOf which none knowWhere its roots run.No aid I received,Not even a sip from the horn.Peering down,I took up the runes –Screaming I grasped them –Then I fell back from there.[13] And this is where the story begins to turn on itself, becoming a cycle in mythic time, an exercise in simultaneity rather than linearity. For the Hávamál poem is known as, “The Words of the High One”[14], and that high one is Odin, the all father, the sacrificial god. Where he takes the runes from may speak to their origins more fully than any allowable evidence, and may afford a continuity, a connection between the sacred symbols of past civilizations. I would argue that the origins of the runes are neither linguistic or exclusively mythic, but sacred feminine magic, held in the trust-memory of pre-historic, Old European civilizations. Their origins and functions have been long obscured. But in order to parallel the runes with both magic and the sacred feminine, there is another aspect of the tale. This is where I find the runes in my own life, again. Runic Mysteries and Skara Brae I may have arrived faster to the runes had I been more brave. In 1998 I traveled to Europe alone, a pilgrimage to the home of my dead grandfather, Sigurd Rosenlund, in Norway. I was supposed to arrive in London, then take a bus tour through England and Scotland, ending in the Orkney islands where there is a ferry direct to Bergen. But at the last minute I canceled. It was my first time traveling alone. I was twenty-three. I was afraid. Fast forward through linear time: I met my teacher Ingrid Kincaid, who calls herself The Rune Woman, in 2013. Through classes and in-depth gnosis work I developed a powerful relationship with the runes, seeing them as individual beings, in the same way each letter is both a symbol and a sound, each rune is the keeper of information. Last year an art commission from Ingrid drew me to the Orkney Islands again and it is there I found in Skara Brae the evidence I sought linking the runes to a deeper history than the Vikings or the Eddas, the comb or the fibula. Skara Brae is a Neolithic settlement in the Orkney Islands inhabited from 3200 BCE to 2200 BCE.[15] This time frame falls partially within the Old European definition of Gimbutas, though outside of the Old European geographical area typically viewed as southern continental Europe. What drew my attention to this particular complex was the presence of “pre-runic” writing. As I looked closely at the symbols carved at Skara Brae I recognized not just “pre-runic” markings, but runes.

THRICE BURNED AND YET SHE LIVES: CLAIMING THE RUNIC FEMININENow she remembers the war,The first in the world,When GullveigWas studded with spears,And in the hall of the High OneShe was burned;Thrice burned,Thrice reborn,Often, many times,And yet she lives.She was called HeiðrWhen she came to a house,The witch who saw many things,She enchanted wands;She enchanted and divined what she could,In a trance she practiced seidrrr,And brought delightTo evil women.--The Poetic Edda, Völuspá[1]Forward This is not a paper. It is a story. And like all stories of mythic time, it has no beginning and no end. As usual, living in perceived non-mythic time, I worry about making the story right, about remembering all of the elements that I am “supposed” to incorporate. As a student new to the study of archaeomythology, I am confronted with a set of “working assumptions”[2] developed by Joan Marler based on the work of Marija Gimbutas. Each assumption could take me in a thousand different directions, and choosing to focus on the fragments and fractures of northern European spiritual symbols feels overwhelming even as I write these words. Marler defines Gimbutas’ archaeomythology as, A discipline that covers such vast territory is intimidating, for I feel I have barely begun over this semester to scratch the surface of interlocking layers, specifically with regard to my subject: the fractured esoteric and religious traditions of northern Europe, defined here as modern Scandinavia, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland and the British Isles.[3] Yet when I sink into the dream of my ancestors, the curators and creators of these ancient artifacts, the runes, whose histories I seek, they laugh at my right and wrong. They say, “There is no one way, there is only the way.” Therefore I ask to honor them, these ancient peoples, their memory, with this work. And I dedicate this writing to Gullveig, the thrice-burned Goddess whose transformative murder in the Poetic Edda attests to the magical power of women in prehistoric northern Europe. Explorations of Gullveig ‘s story illuminate my own standpoint as a feminist scholar and seeker of northern European spirituality. It is through personal relationship with the runes that I have come upon the thread of their origins. It is through speaking the story of Gullveig that still she lives. With permission from the ancestors I seek to narrow the scope of my viewing and look at Joan Marler’s four working assumptions of archaeomythology as detailed by Professor Mara Keller:1. Sacred cosmologies are central to the cultural fabric of all early societies.2. Beliefs and rituals expressing sacred worldviews are conservative and not easily changed.3. Many archaic cultural patterns have survived into the historical period as folk motifs and as mythic elements within oral, visual and ritual traditions.4. Symbols, preserved in cultural artifacts, “represent the grammar and syntax of a kind of meta-language by which an entire constellation of meanings is transmitted.”[4] For the purposes of this paper I will be focusing on the last two assumptions in my investigations: the surviving cultural patterns recorded in the historic Norse myths, and the symbols preserved in northern European archaeology and folklore. It is from this symbolic fabric that my own journey with the runes begins, and where intersections may be found beyond the datable artifacts of recorded history, into the dust-blurred realms of pre-history, where symbols correspond the deep cultures of Old Europe as defined by Marija Gimbutas.[5] Gimbutas looks to the Neolithic in her vast study of Old European civilization, focusing on, “the peoples who inhabited Europe from the 7th to the 3rd millennia BC…referring to Neolithic Europe before the Indo-Europeans.”[6] As I trace back through time before the Vikings, before the Eddas, the Christian transcribed myths of northern Europe written in 13th Century Iceland, before the rune stones, my intuition pricks and my ancestors follow chill fingers up my spine. There is something, here, waiting to be known. Or, as my teacher Ingrid says:“Before the Vikings, before the Christians, before Odin and Thor....the Runes were.”[7]From Whence, the Runes My mother has a pendant inscribed in runes from her father’s hometown of Bergen, Norway. On one side it bears an engraving of a spinning wheel, on the other mysterious writing that captivated me as a child. In early college I paid a student of languages to translate the pendant for me. It was written not in new Norwegian, but in Old Norse and read, “Lake, River, Mountain, Norway.” I thought the words lovely, if pedestrian. I didn’t know that each letter was a rune, each symbol more than a word, but rather a “secret or whispered mystery”[8]. It would be nearly two decades before the runes would come into my life as beings and creatures that sing songs and inform. Modern scholars have puzzled at the origins of the runes. There is a conflict in the interpretation of the runes, for they are seen as either a pragmatic alphabet or a magical, ritual tool.[9] Logical conclusions run that runes were both. Adrian Poruciuc writes, “Much of the mystery that surrounds runes is actually due to the failure of practically all attempts at establishing where, when and by whom runes were “invented.””[10] Amid such flummoxing resistance to a developmental timeline, archaeological evidence appears to be equally obscure. The generally accepted oldest datable (and translatable) runic inscription on an archaeological object is on the Vimose comb from 160 CE Denmark,[11] which appears to bear the name of the comber. And an earlier find, the Meldorf fibula, from 50 CE in North Germany, is possibly a runic inscription…or proto-runic…or Roman,[12] the arguments prevail in the absence of evidence. In looking for the origins of the runes, I turn then to mythology for a clue as to where to pick up a trail deep and historically cold. In the Hávamál, a poem from the Elder Poetic Edda recorded 13th Century CE Iceland, the runes are attributed to a “taking” by the god Odin after sacrifice:I know that I hungOn the wind-blasted treeAll of nights nine,Pierced by my spearAnd given to Odin,Myself sacrificed to myselfOn that poleOf which none knowWhere its roots run.No aid I received,Not even a sip from the horn.Peering down,I took up the runes –Screaming I grasped them –Then I fell back from there.[13] And this is where the story begins to turn on itself, becoming a cycle in mythic time, an exercise in simultaneity rather than linearity. For the Hávamál poem is known as, “The Words of the High One”[14], and that high one is Odin, the all father, the sacrificial god. Where he takes the runes from may speak to their origins more fully than any allowable evidence, and may afford a continuity, a connection between the sacred symbols of past civilizations. I would argue that the origins of the runes are neither linguistic or exclusively mythic, but sacred feminine magic, held in the trust-memory of pre-historic, Old European civilizations. Their origins and functions have been long obscured. But in order to parallel the runes with both magic and the sacred feminine, there is another aspect of the tale. This is where I find the runes in my own life, again. Runic Mysteries and Skara Brae I may have arrived faster to the runes had I been more brave. In 1998 I traveled to Europe alone, a pilgrimage to the home of my dead grandfather, Sigurd Rosenlund, in Norway. I was supposed to arrive in London, then take a bus tour through England and Scotland, ending in the Orkney islands where there is a ferry direct to Bergen. But at the last minute I canceled. It was my first time traveling alone. I was twenty-three. I was afraid. Fast forward through linear time: I met my teacher Ingrid Kincaid, who calls herself The Rune Woman, in 2013. Through classes and in-depth gnosis work I developed a powerful relationship with the runes, seeing them as individual beings, in the same way each letter is both a symbol and a sound, each rune is the keeper of information. Last year an art commission from Ingrid drew me to the Orkney Islands again and it is there I found in Skara Brae the evidence I sought linking the runes to a deeper history than the Vikings or the Eddas, the comb or the fibula. Skara Brae is a Neolithic settlement in the Orkney Islands inhabited from 3200 BCE to 2200 BCE.[15] This time frame falls partially within the Old European definition of Gimbutas, though outside of the Old European geographical area typically viewed as southern continental Europe. What drew my attention to this particular complex was the presence of “pre-runic” writing. As I looked closely at the symbols carved at Skara Brae I recognized not just “pre-runic” markings, but runes.  [16] I had the same feeling of revelation when earlier this semester I saw the diagram of Old European script from Gimbutas’ book, Civilizations of the Goddess. Embedded in the ancient symbolic language of Old Europe are the distinct shapes of multiple runes, as well as numerous markings that parallel those at Skara Brae.

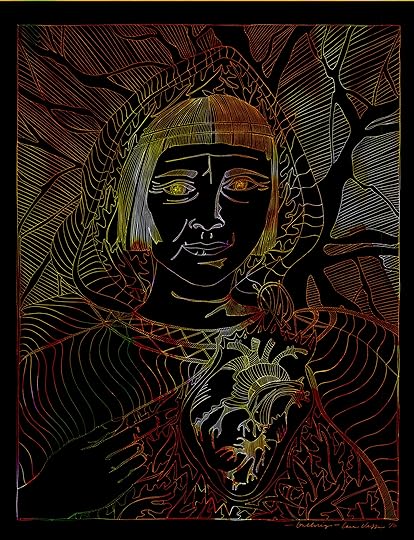

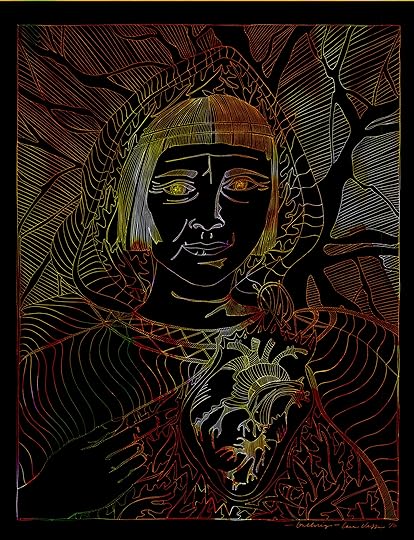

[16] I had the same feeling of revelation when earlier this semester I saw the diagram of Old European script from Gimbutas’ book, Civilizations of the Goddess. Embedded in the ancient symbolic language of Old Europe are the distinct shapes of multiple runes, as well as numerous markings that parallel those at Skara Brae.  [17] In his article, “Old European Echoes in Germanic Runes?” Adrian Poruciuc explores the parallels between the runes and the symbol systems of Old Europe, but resists the linearity/logical theory of development for the runic symbolic alphabet. “Runologists should give up striving to discover a single origin for the Germanic runic script and to view that script as only alphabetic.”[18] He cites the use of runes for divination as part of a broader, symbolic understanding rooted in a magical or sacred context, and parallels many of the rune signs with the Old European script.[19] When I view the ancient script of Old Europe beside the pre-runic symbols of Skara Brae, something stirs in my cells. There is a story here. A story the stones carry. One further artifact from the Orkney Islands is worth mentioning. This from the excavation at the Links of Notland. A tiny human shaped figurine, some 5000 years old. Her body marked with circles for breasts, and a deep V between them. They call her the Orkney Venus.[20] She is the oldest Neolithic human figure discovered in northern Europe. And she is distinctly female. The Runes and the Goddess If the runes are a magical symbol system from Old European culture, then we must turn to the stories, the myths, to further ground ourselves into Marler’s fourth working assumption about archaeomythology. For myths and stories contain sacred symbols, and these too can help us to create a fuller view of lost or obscured worlds. In looking to the myths, I ask: what is the relationship of the feminine to magic in the ancient northern European spiritual traditions? Is there evidence in the myths to support a transitional relationship between the pre-Indo European cultures of northern Europe and the cultures of pre-Indo European Old Europe? To attempt an understanding we turn to explore the ancient threads of the feminine through textual mythology, particularly looking at the stories of the Aesir-Vanir War, The Völva, The Norns, and Gullvieg to try to establish the origins of the runes and their relationship to the feminine. I begin with the storyteller, the potent memory of female magic in ancient northern European culture.The Völva In the Völuspá poem from the Poetic Edda, Odin calls forth a Völva, a witch or seer, from her grave. According to Max Dashú the word völva comes from, “Valr: The Norse name for a ritual staff, valr, gave rise to völva and vala, names for female shamans.”[21] This Völva is ancient, of the race of giants, or Jotun, old enough to remember the beginning of the world, the history of all the nine worlds and all the races:I remember yet | the giants of yore,Who gave me bread | in the days gone by;Nine worlds I knew, | the nine in the treeWith mighty roots | beneath the mold.[22] That the Völva comes from an ancient race that existed prior to Odin’s race of gods, the Aesir, is significant in our search for runic origins, as is the practice of seidr, or shamanic magic, both by Odin and the Völva in the Voluspá. In the Yngling Saga it is written, “Njord's daughter Freyja was priestess of the sacrifices (sei∂r), and first taught the Asaland people the magic art, as it was in use and fashion among the Vanaland people.”[23] In an interesting twist, if Freyja is practiced in the magic arts, she may be a descendant of the Völva Odin wakes by the very magic Freyja teaches him. The Goddess Freyja is one of the Vanir, a race of gods whose name may etymologically be rooted in words meaning “friend,” “pleasure,” or “desire,” and are often associated with fertility, divination and magic.[24] Odin is one of the Aesir, a word of questionable origin and the center of a debate about who are the elder gods in the Norse pantheon. Snorri Sturluson, scribe of the Sagas and Prose Edda in the 13th century, cites the origin of the word Aesir as Ásía, “the Old Norse word for Asia,”[25] which has its uses in the discussion to follow though it is in much debate. The Aesir are referred to as the high gods, or sky gods, and occupy a different realm in the Nine Worlds than the Vanir. The war between the Aesir and the Vanir is described in the Völuspá by the Völva: Now she remembers the wars, the first in the world.[26] That the ancient seeress from the race of Giants would remember the first of all wars is not in itself significant, but the fact that war did not always exist, but had a “first”, and her memory of the cause of the war, is incredibly important. This brings us to Gullveig, source of the first war, and feminine magic. Now she remembers the war,The first in the world,When GullveigWas studded with spears,And in the hall of the High OneShe was burned;Thrice burned,Thrice reborn,Often, many times,And yet she lives.She was called HeiðrWhen she came to a house,The witch who saw many things,She enchanted wands;She enchanted and divined what she could,In a trance she practiced sei∂r,And brought delightTo evil women.[27] The source of the Aesir-Vanir war was the abuse and burning of the Vanir goddess Gullveig. “In the Old Norse tongue, the name Gullveig means “gold drink,” “gold trance,” or “gold power.”’[28] The symbolism of gold in northern Europe is beautifully spoken to by Norse scholar Maria Kvilhaug: “The metal is obviously associated (in Old Norse poetry) with divine brightness, illumination within darkness, great cosmic forces and hidden wisdom.”[29] Gullveig is stabbed with spears, and three times burned, yet she emerges reborn three times as well, reborn as a different Goddess, with a different name, Hei∂. Lindow writes that, “In the sagas Hei∂ is a common name for seeresses, and it is also found in a geneology…presumably giants. The adjective heid, “gleaming,” and the noun heid, “honor,” would suit nicely here as well.”[30] The result of Gullveig’s initiation through death and rebirth is the creation of a powerful feminine presence, Hei∂, the seeress, the practioner of sei∂r magic. She is associated with magic wands, or staffs, prophecy, trance and her relationship with women is established in the final line of the stanza, as she “brings delight to evil women.”[31] The line about evil women in the Völuspá is questioned by Kvilhaug, who states, “The Norse word is illrar, which means bad, or wicked, and is the origin of the English word “ill”, “sick”. I have always suspected the original meaning to be “sick women”, because there are several Norse references to how the goddesses and witches may help sick women…Of course, “bad” can be just another word for unconventional.”[32] She also reminds us that the writers of the Eddas were Christian monks, to whom all feminine magic must be necessarily evil. Of a similar mind, Ralph Metzner translates the word as “contrary.”[33] Gullveig’s transformation is remarkable for its endurance, bringing to mind the transformative initiations of the Eleusinian Mysteries, incorporating the potent magic of death and rebirth into a new cosmic order. That her treatment inspires war between the Aesir and the Vanir is seen by many scholars as reflective of invasion patterns, similar to those described by Gimbutas’ Kurgan Theory. “Since the Vanir are fertility deities, the war has often been understood as the reflection of the overrunning of local fertility cults somewhere in the Germanic area by a more warlike cult, perhaps that of invading Indo-Europeans.”[34] The war ends in peace and reconciliation. From the sacrifice and initiation of Gullveig/Hei∂ emerges a specific form of women’s magic known to the Vanir goddess Freyja. After the peace of the Aesir and the Vanir, which may provide evidence of a partnership between divergent spiritual cosmologies, Freyja moves to Asgard and shares sei∂r with Odin. For this reason, Gullveig/Hei∂ is often seen as an aspect of the goddess Freyja, though I resist this merging due to a personal desire to keep the old stories and Goddesses complex, rather than simplifying them. And it is in the spirit of this complexity that I introduce the Norns who have a role both in women’s magic and in the origins of the runes.The NornsThere stands an ash called Yggdrasil,A mighty tree showered in white hail.From there come the dews that fall in the valleys.It stands evergreen above Urd’s Well.From there come maidens, very wise,Three from the lake that stands beneath the pole.One is called Urd, another Verdandi,Skuld the third; they carve into the treeThe lives and destinies of children.[35] The Norns are mystery figures in Norse myth. They seem to function in multiple ways, primarily as as the keepers of fate or wyrd both as individual spirits (plural: nornir) and as a sort of triple Goddess at the base of the World Tree. In the Völuspá translation above, the Norns emerge from the lake, or well of Ur∂ at the base of the World Tree. Ur∂ means Destiny, ““Ur∂” (pronounced “URD”; Old Norse Urðr, Old English Wyrd) means “destiny.” The Well of Urd could therefore just as aptly be called the Well of Destiny.”[36] Ur∂ is the name of one of the three Norns listed in the passage, as well as Verdandi, “becoming” or “happening,”[37] and Skuld, “is-to-be” or “will happen.”[38] Raven Kaldera says, “All three names of the Nornir bear connotations of evolution of time as a repetitive and circular process…The Nornir are thus "out of time", not bound by the constraints of that evolution.”[39] The Norns’ relationship with simultaneous, spiral or mythic time is potentially significant in the search for the runic connections with the divine feminine. They are from the well of destiny, and simultaneously are destiny itself. They are often seen as weavers, winding the thread of wyrd for individual and cosmic fate. Their number of three parallels an earlier mention in the Voluspá regarding three maidens emerging from Jotunheim, the land of giants:In their dwellings at peace | they played at tables,Of gold no lack | did the gods then know,--Till thither came | up giant-maids three,Huge of might, | out of Jotunheim.[40] The connection of the Norns to the Giants, thus kin to the Völva, is important. The Jotun are considered the primeval race in the Nine Worlds, those who were present at the beginning of historical time, but they are actually pre-historic and thus pre-temporal at least in a linear sense. It makes sense that they would be the keepers of destiny, in the same way the Völva is the keeper of oral history. They transcend the new Gods, both the Aesir and the Vanir, and yet are in a complex series of relationships with them for all of time. Dan McCoy’s translation of the Völuspá says the Norns, “carve into the tree,” but Ralph Metzner translates it as “they carve the staves,” the staves being the runes themselves. In this way we may see the Norns as the originators of the runes. In the next poem after the Völuspá, the Hávamál, Odin details his sacrifice and acquisition of the runes:Peering down,I took up the runes –Screaming I grasped them –Then I fell back from there. Odin is seen as hanging himself from the World Tree, over the Well of Ur∂, taking, grasping, the runes from the well. The well of the Norns is the source of their origin, the source of nourishment for the world tree, and the web of wyrd or fate. Are we to believe that Odin took, grasped the runes, screaming, without their permission? And so the story stretches. In the Völuspá Odin participates in the forced initiation of Gullveig/Heid and sees her receive the power of sei∂r. In the following poem, Odin experiences his own willing initiation, his hanging, his sacrifice, but instead of receiving the power of divine illumination like Gullveig/Hei∂ he has to effort and grasp. When he takes up the runes it feels like an act of appropriation, and it may well be. In the same way he had to learn sei∂r from Freyja, Odin needed to take the runes from the well of the Goddesses of Destiny. They were not freely given, nor did they prevent his grasp. Based on the mythology of the Poetic Edda, the source of magic in northern European pre-Christian traditions appears to be feminine. The origin of the Völva extends back to the race of Giants, to the beginning of time, suggesting that the magical and prophetic abilities of women (at least women of Jotun blood) are innate, primary. The removal of the runes from the well of the Norns posits an origin to the runes from a time before the gods. That Odin has to learn or take magical tools and abilities from women, through what amounts to acts of violence may serve as a metaphor for a transition in northern Europe from women’s power to male power. This isn’t to say that magic and the runes are the exclusive dominion of women. It is to imply that the powers of women in early northern European cultures were significant. In looking at the forms of the runes relative to other Old European script symbols, it would seem there could be a common root. And within Old European cultures there was a powerful reverence for the Goddess and the potency of women as life givers and connectors to divinity. Northern Europe had a divine cosmology that illustrates in myth an initial clash between two “races” of divinities, but the Vanir did not convert to the religion of the invader—presuming the Aesir did represent an invading force of new gods. Instead they made peace, exchanged wisdom, intermarried and co-created new stories together. Women in northern Europe were famously free during the Viking era, able to fight, divorce, hold property and rule in ways women elsewhere were not. The Oseberg ship burial, one of the most resplendent archaeological finds of the Viking age, is dated to 834 CE and contains the remains of two women with staffs.[41] That these women were Völvas seems a distinct possibility. Educator Kari Tauring says that, “Archeologists in Scandinavia have discovered wands (staffs) in about 40 female graves, usually rich graves with valuable grave offerings showing that Völvas belonged to the highest level of society.[42] Tauring also indicates that tradition of the Völva extended into recorded history, and the position of women as diviners and seers in the Germanic tribes was commented on by Julius Caesar and Tacitus.[43] Perhaps the merging of different cosmologies, and the sharing of magic empowered women in northern European societies, and allowed them to retain power even in the face of changing spiritual traditions, until a spiritual climate arrived that could not tolerate other beliefs or perceptions. I speak, of course, of Christianity. Is it possible that the magic of the ancient sacred feminine powers and the runes hold keys for surviving patriarchy and creating partner relationships? If Gullvieg/Hei∂ can transform through death and rebirth, allowing the magic of sei∂r into the world, continuing to practice even after such torment, if Freyja can teach her former enemy the power of this deep, feminine magic even after such tremendous betrayal, if the Norns in their wisdom can allow Odin to take the runes from the well and share their whispered secrets with humankind, what lessons can we, women, who have lived through thousands of years of burning, abuse and theft by patriarchy, learn? This question is poignant for me. I come to the magic of sei∂r as a woman of multiple ancestries, as an American living on beloved but uncertain land, far from my ancestral homes. I come to the runes as a mother to a son and daughters. I come as a seeker of the ways of my ancestors, called to discover their fragments and etchings, called to listen between the lines of their tales. I come afraid, for I have been taught to fear this wisdom of the symbols of my heritage due to their corruption and misappropriation in recent history. And I come unafraid, for the deeper I travel the more I find that sings to me. When we claim the runic feminine, when we stretch the threads of fate back far enough, through pre-history, and view their shapes, we claim our own pain and capacity for power, magic, and healing. As we step toward the fire, once again, we can remember that in death is transformation, rebirth, the greater mysteries. In this story that is my story, that is your story, reader, as you participate too, like the Norns, beyond the bounds of logical time and space, in the mythic cycle of creation, there is potential. A soul seed as rich as the one the Völva knows, from the beginning of time. In such a seed grows the world tree. [1] Dan McCoy, “Gullvieg,” Norse Mythology for Smart People, last modified May 12, 2016, http://norse-mythology.org/gullveig/. I prefer McCoy’s sensitive and nuanced translation of the Poetic Edda to the commonly quoted Henry Adams Bellows version from 1936.[2] Mara Keller, “Archaeomythology as Academic Field and Methodology Bridging Science and Religion, Empiricism and Spirituality,” class distributed article, 3.[3] Joan Marler, “The Body of Woman as Sacred Metaphor,” Adrian Poruciuc, “Old European Echoes in Germanic Runes?” Journal of Archaeomythology 7, (2011): 67.[4] Keller 4 quoting Joan Marler “Introduction to Archaeomythology,” ReVision Journal 23, 1 (Summer): 2, quoted in Keller, “Archaeomythology,” 3-4.[5] Marija Gimbutas, Civilizations of the Goddess (New York: Harper Collins, 1991), vii.[6]Ibid., vii.[7] Ingrid Kincaid, The Runes Revealed (Portland, OR: Inkwater Press, 2016), 1.[8] Susan Gray, The Woman’s Book of Runes, (New York: Barnes and Noble Books), 2.[9] Adrian Poruciuc, “Old European Echoes in Germanic Runes?” Journal of Archaeomythology 7, (2011): 67.[10] Ibid., 68.[11] Tineke Looijenga, “Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions,” Odroerir Journal Online Academic Library, (2014): 9. http://odroerirjournal.com/download/L... Ibid 9[13] Dan McCoy, “Origins of the Runes,” Norse Mythology for Smart People, http://norse-mythology.org/runes/the-... John Lindow, Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 164.[15] Skara Brae The Discovery and Excavation of Orkney’s Finest Neolithic Settlement, Orkneyjar, last modified February 25, 2016, http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/skar... Yan Goudryan, “Skara Brae and Neolithic Science,” The Creation of Time: A Philosophy of Science Blog, December 6th 2010, http://www.goudryan.com/the-coft/skar... Gimbutas, The Civilization of the Goddess, 310.[18] Poruciuc, “Old European Echoes,” 71.[19] Ibid., 70.[20] “Orkney Venus—early people—Scotland’s History,” Education Scotland, accessed May 16, 2016. http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/s... Max Dashu, “Woman Shaman Transcript of Disc 2: Staffs,” Suppressed Histories, last modified 2013, http://www.suppressedhistories.net/wo... Henry Adams Bellows, The Poetic Edda: Voluspo, Internet Sacred Texts Archive, accessed May 17, 2016, http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/poe/p.... I am using the Bellows translation here for clarity around the image of the World Tree.[23] Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla, The Online Medieval and Classical Library, last update unknown, http://omacl.org/Heimskringla/.[24] John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 311.[25] Ibid., 50.[26] Ibid., 51.[27] Dan McCoy, “Gullveig,” http://norse-mythology.org/gullveig/.... Ralph Metzner, “Freyja and the Vanir Earth Deities,” The Well of Remembrance: Rediscovering the Earth Wisdom Myths of Northern Europe, (Boston, MA: Shambhala, 1994), 166.[29] Maria Kvilhaug, “Burning the Witch! – The Initiation of the Goddess and the War of the Aesir and the Vanir,” Freyia Völundarhúsins Lady of the Labyrinth´s Old Norse Mythology Website, last update 2016, http://freya.theladyofthelabyrinth.co... John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 165.[31] Dan McCoy, “Gullveig,” http://norse-mythology.org/gullveig/.... Maria Kvilhaug, “Burning the Witch,” http://freya.theladyofthelabyrinth.co... Ralph Metzner, The Well of Remembrance, 167.[34] John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 53.[35] Dan McCoy, “The Origins of the Runes,” Norse Mythology for Smart People, http://norse-mythology.org/runes/the-... .[36] Dan McCoy, “Yggdrasil and the Well of Urd,” http://norse-mythology.org/cosmology/... John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 245.[38] Ibid 245[39] Raven Kaldera, “Shrine to the Norns,” Northern Paganism, last update unknown, http://www.northernpaganism.org/shrin... Henry Adams Bellows, Poetic Edda: Voluspo, http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/poe/p.... I use the Bellows translation here for the clear image of the giant maidens emerging from Jotunheim.[41] “The Oseberg Finds,” University of Oslo Museum of Cultural History, last modified December 10, 2012, http://www.khm.uio.no/english/visit-u... Kari Tauring, “What is a Völva?” last modified October 31, 2011, http://karitauring.com/what-is-a-Völv... Kari Tauring, “What is a Völva?” http://karitauring.com/what-is-a-Völva/.

[17] In his article, “Old European Echoes in Germanic Runes?” Adrian Poruciuc explores the parallels between the runes and the symbol systems of Old Europe, but resists the linearity/logical theory of development for the runic symbolic alphabet. “Runologists should give up striving to discover a single origin for the Germanic runic script and to view that script as only alphabetic.”[18] He cites the use of runes for divination as part of a broader, symbolic understanding rooted in a magical or sacred context, and parallels many of the rune signs with the Old European script.[19] When I view the ancient script of Old Europe beside the pre-runic symbols of Skara Brae, something stirs in my cells. There is a story here. A story the stones carry. One further artifact from the Orkney Islands is worth mentioning. This from the excavation at the Links of Notland. A tiny human shaped figurine, some 5000 years old. Her body marked with circles for breasts, and a deep V between them. They call her the Orkney Venus.[20] She is the oldest Neolithic human figure discovered in northern Europe. And she is distinctly female. The Runes and the Goddess If the runes are a magical symbol system from Old European culture, then we must turn to the stories, the myths, to further ground ourselves into Marler’s fourth working assumption about archaeomythology. For myths and stories contain sacred symbols, and these too can help us to create a fuller view of lost or obscured worlds. In looking to the myths, I ask: what is the relationship of the feminine to magic in the ancient northern European spiritual traditions? Is there evidence in the myths to support a transitional relationship between the pre-Indo European cultures of northern Europe and the cultures of pre-Indo European Old Europe? To attempt an understanding we turn to explore the ancient threads of the feminine through textual mythology, particularly looking at the stories of the Aesir-Vanir War, The Völva, The Norns, and Gullvieg to try to establish the origins of the runes and their relationship to the feminine. I begin with the storyteller, the potent memory of female magic in ancient northern European culture.The Völva In the Völuspá poem from the Poetic Edda, Odin calls forth a Völva, a witch or seer, from her grave. According to Max Dashú the word völva comes from, “Valr: The Norse name for a ritual staff, valr, gave rise to völva and vala, names for female shamans.”[21] This Völva is ancient, of the race of giants, or Jotun, old enough to remember the beginning of the world, the history of all the nine worlds and all the races:I remember yet | the giants of yore,Who gave me bread | in the days gone by;Nine worlds I knew, | the nine in the treeWith mighty roots | beneath the mold.[22] That the Völva comes from an ancient race that existed prior to Odin’s race of gods, the Aesir, is significant in our search for runic origins, as is the practice of seidr, or shamanic magic, both by Odin and the Völva in the Voluspá. In the Yngling Saga it is written, “Njord's daughter Freyja was priestess of the sacrifices (sei∂r), and first taught the Asaland people the magic art, as it was in use and fashion among the Vanaland people.”[23] In an interesting twist, if Freyja is practiced in the magic arts, she may be a descendant of the Völva Odin wakes by the very magic Freyja teaches him. The Goddess Freyja is one of the Vanir, a race of gods whose name may etymologically be rooted in words meaning “friend,” “pleasure,” or “desire,” and are often associated with fertility, divination and magic.[24] Odin is one of the Aesir, a word of questionable origin and the center of a debate about who are the elder gods in the Norse pantheon. Snorri Sturluson, scribe of the Sagas and Prose Edda in the 13th century, cites the origin of the word Aesir as Ásía, “the Old Norse word for Asia,”[25] which has its uses in the discussion to follow though it is in much debate. The Aesir are referred to as the high gods, or sky gods, and occupy a different realm in the Nine Worlds than the Vanir. The war between the Aesir and the Vanir is described in the Völuspá by the Völva: Now she remembers the wars, the first in the world.[26] That the ancient seeress from the race of Giants would remember the first of all wars is not in itself significant, but the fact that war did not always exist, but had a “first”, and her memory of the cause of the war, is incredibly important. This brings us to Gullveig, source of the first war, and feminine magic. Now she remembers the war,The first in the world,When GullveigWas studded with spears,And in the hall of the High OneShe was burned;Thrice burned,Thrice reborn,Often, many times,And yet she lives.She was called HeiðrWhen she came to a house,The witch who saw many things,She enchanted wands;She enchanted and divined what she could,In a trance she practiced sei∂r,And brought delightTo evil women.[27] The source of the Aesir-Vanir war was the abuse and burning of the Vanir goddess Gullveig. “In the Old Norse tongue, the name Gullveig means “gold drink,” “gold trance,” or “gold power.”’[28] The symbolism of gold in northern Europe is beautifully spoken to by Norse scholar Maria Kvilhaug: “The metal is obviously associated (in Old Norse poetry) with divine brightness, illumination within darkness, great cosmic forces and hidden wisdom.”[29] Gullveig is stabbed with spears, and three times burned, yet she emerges reborn three times as well, reborn as a different Goddess, with a different name, Hei∂. Lindow writes that, “In the sagas Hei∂ is a common name for seeresses, and it is also found in a geneology…presumably giants. The adjective heid, “gleaming,” and the noun heid, “honor,” would suit nicely here as well.”[30] The result of Gullveig’s initiation through death and rebirth is the creation of a powerful feminine presence, Hei∂, the seeress, the practioner of sei∂r magic. She is associated with magic wands, or staffs, prophecy, trance and her relationship with women is established in the final line of the stanza, as she “brings delight to evil women.”[31] The line about evil women in the Völuspá is questioned by Kvilhaug, who states, “The Norse word is illrar, which means bad, or wicked, and is the origin of the English word “ill”, “sick”. I have always suspected the original meaning to be “sick women”, because there are several Norse references to how the goddesses and witches may help sick women…Of course, “bad” can be just another word for unconventional.”[32] She also reminds us that the writers of the Eddas were Christian monks, to whom all feminine magic must be necessarily evil. Of a similar mind, Ralph Metzner translates the word as “contrary.”[33] Gullveig’s transformation is remarkable for its endurance, bringing to mind the transformative initiations of the Eleusinian Mysteries, incorporating the potent magic of death and rebirth into a new cosmic order. That her treatment inspires war between the Aesir and the Vanir is seen by many scholars as reflective of invasion patterns, similar to those described by Gimbutas’ Kurgan Theory. “Since the Vanir are fertility deities, the war has often been understood as the reflection of the overrunning of local fertility cults somewhere in the Germanic area by a more warlike cult, perhaps that of invading Indo-Europeans.”[34] The war ends in peace and reconciliation. From the sacrifice and initiation of Gullveig/Hei∂ emerges a specific form of women’s magic known to the Vanir goddess Freyja. After the peace of the Aesir and the Vanir, which may provide evidence of a partnership between divergent spiritual cosmologies, Freyja moves to Asgard and shares sei∂r with Odin. For this reason, Gullveig/Hei∂ is often seen as an aspect of the goddess Freyja, though I resist this merging due to a personal desire to keep the old stories and Goddesses complex, rather than simplifying them. And it is in the spirit of this complexity that I introduce the Norns who have a role both in women’s magic and in the origins of the runes.The NornsThere stands an ash called Yggdrasil,A mighty tree showered in white hail.From there come the dews that fall in the valleys.It stands evergreen above Urd’s Well.From there come maidens, very wise,Three from the lake that stands beneath the pole.One is called Urd, another Verdandi,Skuld the third; they carve into the treeThe lives and destinies of children.[35] The Norns are mystery figures in Norse myth. They seem to function in multiple ways, primarily as as the keepers of fate or wyrd both as individual spirits (plural: nornir) and as a sort of triple Goddess at the base of the World Tree. In the Völuspá translation above, the Norns emerge from the lake, or well of Ur∂ at the base of the World Tree. Ur∂ means Destiny, ““Ur∂” (pronounced “URD”; Old Norse Urðr, Old English Wyrd) means “destiny.” The Well of Urd could therefore just as aptly be called the Well of Destiny.”[36] Ur∂ is the name of one of the three Norns listed in the passage, as well as Verdandi, “becoming” or “happening,”[37] and Skuld, “is-to-be” or “will happen.”[38] Raven Kaldera says, “All three names of the Nornir bear connotations of evolution of time as a repetitive and circular process…The Nornir are thus "out of time", not bound by the constraints of that evolution.”[39] The Norns’ relationship with simultaneous, spiral or mythic time is potentially significant in the search for the runic connections with the divine feminine. They are from the well of destiny, and simultaneously are destiny itself. They are often seen as weavers, winding the thread of wyrd for individual and cosmic fate. Their number of three parallels an earlier mention in the Voluspá regarding three maidens emerging from Jotunheim, the land of giants:In their dwellings at peace | they played at tables,Of gold no lack | did the gods then know,--Till thither came | up giant-maids three,Huge of might, | out of Jotunheim.[40] The connection of the Norns to the Giants, thus kin to the Völva, is important. The Jotun are considered the primeval race in the Nine Worlds, those who were present at the beginning of historical time, but they are actually pre-historic and thus pre-temporal at least in a linear sense. It makes sense that they would be the keepers of destiny, in the same way the Völva is the keeper of oral history. They transcend the new Gods, both the Aesir and the Vanir, and yet are in a complex series of relationships with them for all of time. Dan McCoy’s translation of the Völuspá says the Norns, “carve into the tree,” but Ralph Metzner translates it as “they carve the staves,” the staves being the runes themselves. In this way we may see the Norns as the originators of the runes. In the next poem after the Völuspá, the Hávamál, Odin details his sacrifice and acquisition of the runes:Peering down,I took up the runes –Screaming I grasped them –Then I fell back from there. Odin is seen as hanging himself from the World Tree, over the Well of Ur∂, taking, grasping, the runes from the well. The well of the Norns is the source of their origin, the source of nourishment for the world tree, and the web of wyrd or fate. Are we to believe that Odin took, grasped the runes, screaming, without their permission? And so the story stretches. In the Völuspá Odin participates in the forced initiation of Gullveig/Heid and sees her receive the power of sei∂r. In the following poem, Odin experiences his own willing initiation, his hanging, his sacrifice, but instead of receiving the power of divine illumination like Gullveig/Hei∂ he has to effort and grasp. When he takes up the runes it feels like an act of appropriation, and it may well be. In the same way he had to learn sei∂r from Freyja, Odin needed to take the runes from the well of the Goddesses of Destiny. They were not freely given, nor did they prevent his grasp. Based on the mythology of the Poetic Edda, the source of magic in northern European pre-Christian traditions appears to be feminine. The origin of the Völva extends back to the race of Giants, to the beginning of time, suggesting that the magical and prophetic abilities of women (at least women of Jotun blood) are innate, primary. The removal of the runes from the well of the Norns posits an origin to the runes from a time before the gods. That Odin has to learn or take magical tools and abilities from women, through what amounts to acts of violence may serve as a metaphor for a transition in northern Europe from women’s power to male power. This isn’t to say that magic and the runes are the exclusive dominion of women. It is to imply that the powers of women in early northern European cultures were significant. In looking at the forms of the runes relative to other Old European script symbols, it would seem there could be a common root. And within Old European cultures there was a powerful reverence for the Goddess and the potency of women as life givers and connectors to divinity. Northern Europe had a divine cosmology that illustrates in myth an initial clash between two “races” of divinities, but the Vanir did not convert to the religion of the invader—presuming the Aesir did represent an invading force of new gods. Instead they made peace, exchanged wisdom, intermarried and co-created new stories together. Women in northern Europe were famously free during the Viking era, able to fight, divorce, hold property and rule in ways women elsewhere were not. The Oseberg ship burial, one of the most resplendent archaeological finds of the Viking age, is dated to 834 CE and contains the remains of two women with staffs.[41] That these women were Völvas seems a distinct possibility. Educator Kari Tauring says that, “Archeologists in Scandinavia have discovered wands (staffs) in about 40 female graves, usually rich graves with valuable grave offerings showing that Völvas belonged to the highest level of society.[42] Tauring also indicates that tradition of the Völva extended into recorded history, and the position of women as diviners and seers in the Germanic tribes was commented on by Julius Caesar and Tacitus.[43] Perhaps the merging of different cosmologies, and the sharing of magic empowered women in northern European societies, and allowed them to retain power even in the face of changing spiritual traditions, until a spiritual climate arrived that could not tolerate other beliefs or perceptions. I speak, of course, of Christianity. Is it possible that the magic of the ancient sacred feminine powers and the runes hold keys for surviving patriarchy and creating partner relationships? If Gullvieg/Hei∂ can transform through death and rebirth, allowing the magic of sei∂r into the world, continuing to practice even after such torment, if Freyja can teach her former enemy the power of this deep, feminine magic even after such tremendous betrayal, if the Norns in their wisdom can allow Odin to take the runes from the well and share their whispered secrets with humankind, what lessons can we, women, who have lived through thousands of years of burning, abuse and theft by patriarchy, learn? This question is poignant for me. I come to the magic of sei∂r as a woman of multiple ancestries, as an American living on beloved but uncertain land, far from my ancestral homes. I come to the runes as a mother to a son and daughters. I come as a seeker of the ways of my ancestors, called to discover their fragments and etchings, called to listen between the lines of their tales. I come afraid, for I have been taught to fear this wisdom of the symbols of my heritage due to their corruption and misappropriation in recent history. And I come unafraid, for the deeper I travel the more I find that sings to me. When we claim the runic feminine, when we stretch the threads of fate back far enough, through pre-history, and view their shapes, we claim our own pain and capacity for power, magic, and healing. As we step toward the fire, once again, we can remember that in death is transformation, rebirth, the greater mysteries. In this story that is my story, that is your story, reader, as you participate too, like the Norns, beyond the bounds of logical time and space, in the mythic cycle of creation, there is potential. A soul seed as rich as the one the Völva knows, from the beginning of time. In such a seed grows the world tree. [1] Dan McCoy, “Gullvieg,” Norse Mythology for Smart People, last modified May 12, 2016, http://norse-mythology.org/gullveig/. I prefer McCoy’s sensitive and nuanced translation of the Poetic Edda to the commonly quoted Henry Adams Bellows version from 1936.[2] Mara Keller, “Archaeomythology as Academic Field and Methodology Bridging Science and Religion, Empiricism and Spirituality,” class distributed article, 3.[3] Joan Marler, “The Body of Woman as Sacred Metaphor,” Adrian Poruciuc, “Old European Echoes in Germanic Runes?” Journal of Archaeomythology 7, (2011): 67.[4] Keller 4 quoting Joan Marler “Introduction to Archaeomythology,” ReVision Journal 23, 1 (Summer): 2, quoted in Keller, “Archaeomythology,” 3-4.[5] Marija Gimbutas, Civilizations of the Goddess (New York: Harper Collins, 1991), vii.[6]Ibid., vii.[7] Ingrid Kincaid, The Runes Revealed (Portland, OR: Inkwater Press, 2016), 1.[8] Susan Gray, The Woman’s Book of Runes, (New York: Barnes and Noble Books), 2.[9] Adrian Poruciuc, “Old European Echoes in Germanic Runes?” Journal of Archaeomythology 7, (2011): 67.[10] Ibid., 68.[11] Tineke Looijenga, “Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions,” Odroerir Journal Online Academic Library, (2014): 9. http://odroerirjournal.com/download/L... Ibid 9[13] Dan McCoy, “Origins of the Runes,” Norse Mythology for Smart People, http://norse-mythology.org/runes/the-... John Lindow, Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 164.[15] Skara Brae The Discovery and Excavation of Orkney’s Finest Neolithic Settlement, Orkneyjar, last modified February 25, 2016, http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/skar... Yan Goudryan, “Skara Brae and Neolithic Science,” The Creation of Time: A Philosophy of Science Blog, December 6th 2010, http://www.goudryan.com/the-coft/skar... Gimbutas, The Civilization of the Goddess, 310.[18] Poruciuc, “Old European Echoes,” 71.[19] Ibid., 70.[20] “Orkney Venus—early people—Scotland’s History,” Education Scotland, accessed May 16, 2016. http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/s... Max Dashu, “Woman Shaman Transcript of Disc 2: Staffs,” Suppressed Histories, last modified 2013, http://www.suppressedhistories.net/wo... Henry Adams Bellows, The Poetic Edda: Voluspo, Internet Sacred Texts Archive, accessed May 17, 2016, http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/poe/p.... I am using the Bellows translation here for clarity around the image of the World Tree.[23] Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla, The Online Medieval and Classical Library, last update unknown, http://omacl.org/Heimskringla/.[24] John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 311.[25] Ibid., 50.[26] Ibid., 51.[27] Dan McCoy, “Gullveig,” http://norse-mythology.org/gullveig/.... Ralph Metzner, “Freyja and the Vanir Earth Deities,” The Well of Remembrance: Rediscovering the Earth Wisdom Myths of Northern Europe, (Boston, MA: Shambhala, 1994), 166.[29] Maria Kvilhaug, “Burning the Witch! – The Initiation of the Goddess and the War of the Aesir and the Vanir,” Freyia Völundarhúsins Lady of the Labyrinth´s Old Norse Mythology Website, last update 2016, http://freya.theladyofthelabyrinth.co... John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 165.[31] Dan McCoy, “Gullveig,” http://norse-mythology.org/gullveig/.... Maria Kvilhaug, “Burning the Witch,” http://freya.theladyofthelabyrinth.co... Ralph Metzner, The Well of Remembrance, 167.[34] John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 53.[35] Dan McCoy, “The Origins of the Runes,” Norse Mythology for Smart People, http://norse-mythology.org/runes/the-... .[36] Dan McCoy, “Yggdrasil and the Well of Urd,” http://norse-mythology.org/cosmology/... John Lindow, Norse Mythology, 245.[38] Ibid 245[39] Raven Kaldera, “Shrine to the Norns,” Northern Paganism, last update unknown, http://www.northernpaganism.org/shrin... Henry Adams Bellows, Poetic Edda: Voluspo, http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/poe/p.... I use the Bellows translation here for the clear image of the giant maidens emerging from Jotunheim.[41] “The Oseberg Finds,” University of Oslo Museum of Cultural History, last modified December 10, 2012, http://www.khm.uio.no/english/visit-u... Kari Tauring, “What is a Völva?” last modified October 31, 2011, http://karitauring.com/what-is-a-Völv... Kari Tauring, “What is a Völva?” http://karitauring.com/what-is-a-Völva/.

THRICE BURNED AND YET SHE LIVES: CLAIMING THE RUNIC FEMININENow she remembers the war,The first in the world,When GullveigWas studded with spears,And in the hall of the High OneShe was burned;Thrice burned,Thrice reborn,Often, many times,And yet she lives.She was called HeiðrWhen she came to a house,The witch who saw many things,She enchanted wands;She enchanted and divined what she could,In a trance she practiced seidrrr,And brought delightTo evil women.--The Poetic Edda, Völuspá[1]Forward This is not a paper. It is a story. And like all stories of mythic time, it has no beginning and no end. As usual, living in perceived non-mythic time, I worry about making the story right, about remembering all of the elements that I am “supposed” to incorporate. As a student new to the study of archaeomythology, I am confronted with a set of “working assumptions”[2] developed by Joan Marler based on the work of Marija Gimbutas. Each assumption could take me in a thousand different directions, and choosing to focus on the fragments and fractures of northern European spiritual symbols feels overwhelming even as I write these words. Marler defines Gimbutas’ archaeomythology as, A discipline that covers such vast territory is intimidating, for I feel I have barely begun over this semester to scratch the surface of interlocking layers, specifically with regard to my subject: the fractured esoteric and religious traditions of northern Europe, defined here as modern Scandinavia, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland and the British Isles.[3] Yet when I sink into the dream of my ancestors, the curators and creators of these ancient artifacts, the runes, whose histories I seek, they laugh at my right and wrong. They say, “There is no one way, there is only the way.” Therefore I ask to honor them, these ancient peoples, their memory, with this work. And I dedicate this writing to Gullveig, the thrice-burned Goddess whose transformative murder in the Poetic Edda attests to the magical power of women in prehistoric northern Europe. Explorations of Gullveig ‘s story illuminate my own standpoint as a feminist scholar and seeker of northern European spirituality. It is through personal relationship with the runes that I have come upon the thread of their origins. It is through speaking the story of Gullveig that still she lives. With permission from the ancestors I seek to narrow the scope of my viewing and look at Joan Marler’s four working assumptions of archaeomythology as detailed by Professor Mara Keller:1. Sacred cosmologies are central to the cultural fabric of all early societies.2. Beliefs and rituals expressing sacred worldviews are conservative and not easily changed.3. Many archaic cultural patterns have survived into the historical period as folk motifs and as mythic elements within oral, visual and ritual traditions.4. Symbols, preserved in cultural artifacts, “represent the grammar and syntax of a kind of meta-language by which an entire constellation of meanings is transmitted.”[4] For the purposes of this paper I will be focusing on the last two assumptions in my investigations: the surviving cultural patterns recorded in the historic Norse myths, and the symbols preserved in northern European archaeology and folklore. It is from this symbolic fabric that my own journey with the runes begins, and where intersections may be found beyond the datable artifacts of recorded history, into the dust-blurred realms of pre-history, where symbols correspond the deep cultures of Old Europe as defined by Marija Gimbutas.[5] Gimbutas looks to the Neolithic in her vast study of Old European civilization, focusing on, “the peoples who inhabited Europe from the 7th to the 3rd millennia BC…referring to Neolithic Europe before the Indo-Europeans.”[6] As I trace back through time before the Vikings, before the Eddas, the Christian transcribed myths of northern Europe written in 13th Century Iceland, before the rune stones, my intuition pricks and my ancestors follow chill fingers up my spine. There is something, here, waiting to be known. Or, as my teacher Ingrid says:“Before the Vikings, before the Christians, before Odin and Thor....the Runes were.”[7]From Whence, the Runes My mother has a pendant inscribed in runes from her father’s hometown of Bergen, Norway. On one side it bears an engraving of a spinning wheel, on the other mysterious writing that captivated me as a child. In early college I paid a student of languages to translate the pendant for me. It was written not in new Norwegian, but in Old Norse and read, “Lake, River, Mountain, Norway.” I thought the words lovely, if pedestrian. I didn’t know that each letter was a rune, each symbol more than a word, but rather a “secret or whispered mystery”[8]. It would be nearly two decades before the runes would come into my life as beings and creatures that sing songs and inform. Modern scholars have puzzled at the origins of the runes. There is a conflict in the interpretation of the runes, for they are seen as either a pragmatic alphabet or a magical, ritual tool.[9] Logical conclusions run that runes were both. Adrian Poruciuc writes, “Much of the mystery that surrounds runes is actually due to the failure of practically all attempts at establishing where, when and by whom runes were “invented.””[10] Amid such flummoxing resistance to a developmental timeline, archaeological evidence appears to be equally obscure. The generally accepted oldest datable (and translatable) runic inscription on an archaeological object is on the Vimose comb from 160 CE Denmark,[11] which appears to bear the name of the comber. And an earlier find, the Meldorf fibula, from 50 CE in North Germany, is possibly a runic inscription…or proto-runic…or Roman,[12] the arguments prevail in the absence of evidence. In looking for the origins of the runes, I turn then to mythology for a clue as to where to pick up a trail deep and historically cold. In the Hávamál, a poem from the Elder Poetic Edda recorded 13th Century CE Iceland, the runes are attributed to a “taking” by the god Odin after sacrifice:I know that I hungOn the wind-blasted treeAll of nights nine,Pierced by my spearAnd given to Odin,Myself sacrificed to myselfOn that poleOf which none knowWhere its roots run.No aid I received,Not even a sip from the horn.Peering down,I took up the runes –Screaming I grasped them –Then I fell back from there.[13] And this is where the story begins to turn on itself, becoming a cycle in mythic time, an exercise in simultaneity rather than linearity. For the Hávamál poem is known as, “The Words of the High One”[14], and that high one is Odin, the all father, the sacrificial god. Where he takes the runes from may speak to their origins more fully than any allowable evidence, and may afford a continuity, a connection between the sacred symbols of past civilizations. I would argue that the origins of the runes are neither linguistic or exclusively mythic, but sacred feminine magic, held in the trust-memory of pre-historic, Old European civilizations. Their origins and functions have been long obscured. But in order to parallel the runes with both magic and the sacred feminine, there is another aspect of the tale. This is where I find the runes in my own life, again. Runic Mysteries and Skara Brae I may have arrived faster to the runes had I been more brave. In 1998 I traveled to Europe alone, a pilgrimage to the home of my dead grandfather, Sigurd Rosenlund, in Norway. I was supposed to arrive in London, then take a bus tour through England and Scotland, ending in the Orkney islands where there is a ferry direct to Bergen. But at the last minute I canceled. It was my first time traveling alone. I was twenty-three. I was afraid. Fast forward through linear time: I met my teacher Ingrid Kincaid, who calls herself The Rune Woman, in 2013. Through classes and in-depth gnosis work I developed a powerful relationship with the runes, seeing them as individual beings, in the same way each letter is both a symbol and a sound, each rune is the keeper of information. Last year an art commission from Ingrid drew me to the Orkney Islands again and it is there I found in Skara Brae the evidence I sought linking the runes to a deeper history than the Vikings or the Eddas, the comb or the fibula. Skara Brae is a Neolithic settlement in the Orkney Islands inhabited from 3200 BCE to 2200 BCE.[15] This time frame falls partially within the Old European definition of Gimbutas, though outside of the Old European geographical area typically viewed as southern continental Europe. What drew my attention to this particular complex was the presence of “pre-runic” writing. As I looked closely at the symbols carved at Skara Brae I recognized not just “pre-runic” markings, but runes.

THRICE BURNED AND YET SHE LIVES: CLAIMING THE RUNIC FEMININENow she remembers the war,The first in the world,When GullveigWas studded with spears,And in the hall of the High OneShe was burned;Thrice burned,Thrice reborn,Often, many times,And yet she lives.She was called HeiðrWhen she came to a house,The witch who saw many things,She enchanted wands;She enchanted and divined what she could,In a trance she practiced seidrrr,And brought delightTo evil women.--The Poetic Edda, Völuspá[1]Forward This is not a paper. It is a story. And like all stories of mythic time, it has no beginning and no end. As usual, living in perceived non-mythic time, I worry about making the story right, about remembering all of the elements that I am “supposed” to incorporate. As a student new to the study of archaeomythology, I am confronted with a set of “working assumptions”[2] developed by Joan Marler based on the work of Marija Gimbutas. Each assumption could take me in a thousand different directions, and choosing to focus on the fragments and fractures of northern European spiritual symbols feels overwhelming even as I write these words. Marler defines Gimbutas’ archaeomythology as, A discipline that covers such vast territory is intimidating, for I feel I have barely begun over this semester to scratch the surface of interlocking layers, specifically with regard to my subject: the fractured esoteric and religious traditions of northern Europe, defined here as modern Scandinavia, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland and the British Isles.[3] Yet when I sink into the dream of my ancestors, the curators and creators of these ancient artifacts, the runes, whose histories I seek, they laugh at my right and wrong. They say, “There is no one way, there is only the way.” Therefore I ask to honor them, these ancient peoples, their memory, with this work. And I dedicate this writing to Gullveig, the thrice-burned Goddess whose transformative murder in the Poetic Edda attests to the magical power of women in prehistoric northern Europe. Explorations of Gullveig ‘s story illuminate my own standpoint as a feminist scholar and seeker of northern European spirituality. It is through personal relationship with the runes that I have come upon the thread of their origins. It is through speaking the story of Gullveig that still she lives. With permission from the ancestors I seek to narrow the scope of my viewing and look at Joan Marler’s four working assumptions of archaeomythology as detailed by Professor Mara Keller:1. Sacred cosmologies are central to the cultural fabric of all early societies.2. Beliefs and rituals expressing sacred worldviews are conservative and not easily changed.3. Many archaic cultural patterns have survived into the historical period as folk motifs and as mythic elements within oral, visual and ritual traditions.4. Symbols, preserved in cultural artifacts, “represent the grammar and syntax of a kind of meta-language by which an entire constellation of meanings is transmitted.”[4] For the purposes of this paper I will be focusing on the last two assumptions in my investigations: the surviving cultural patterns recorded in the historic Norse myths, and the symbols preserved in northern European archaeology and folklore. It is from this symbolic fabric that my own journey with the runes begins, and where intersections may be found beyond the datable artifacts of recorded history, into the dust-blurred realms of pre-history, where symbols correspond the deep cultures of Old Europe as defined by Marija Gimbutas.[5] Gimbutas looks to the Neolithic in her vast study of Old European civilization, focusing on, “the peoples who inhabited Europe from the 7th to the 3rd millennia BC…referring to Neolithic Europe before the Indo-Europeans.”[6] As I trace back through time before the Vikings, before the Eddas, the Christian transcribed myths of northern Europe written in 13th Century Iceland, before the rune stones, my intuition pricks and my ancestors follow chill fingers up my spine. There is something, here, waiting to be known. Or, as my teacher Ingrid says:“Before the Vikings, before the Christians, before Odin and Thor....the Runes were.”[7]From Whence, the Runes My mother has a pendant inscribed in runes from her father’s hometown of Bergen, Norway. On one side it bears an engraving of a spinning wheel, on the other mysterious writing that captivated me as a child. In early college I paid a student of languages to translate the pendant for me. It was written not in new Norwegian, but in Old Norse and read, “Lake, River, Mountain, Norway.” I thought the words lovely, if pedestrian. I didn’t know that each letter was a rune, each symbol more than a word, but rather a “secret or whispered mystery”[8]. It would be nearly two decades before the runes would come into my life as beings and creatures that sing songs and inform. Modern scholars have puzzled at the origins of the runes. There is a conflict in the interpretation of the runes, for they are seen as either a pragmatic alphabet or a magical, ritual tool.[9] Logical conclusions run that runes were both. Adrian Poruciuc writes, “Much of the mystery that surrounds runes is actually due to the failure of practically all attempts at establishing where, when and by whom runes were “invented.””[10] Amid such flummoxing resistance to a developmental timeline, archaeological evidence appears to be equally obscure. The generally accepted oldest datable (and translatable) runic inscription on an archaeological object is on the Vimose comb from 160 CE Denmark,[11] which appears to bear the name of the comber. And an earlier find, the Meldorf fibula, from 50 CE in North Germany, is possibly a runic inscription…or proto-runic…or Roman,[12] the arguments prevail in the absence of evidence. In looking for the origins of the runes, I turn then to mythology for a clue as to where to pick up a trail deep and historically cold. In the Hávamál, a poem from the Elder Poetic Edda recorded 13th Century CE Iceland, the runes are attributed to a “taking” by the god Odin after sacrifice:I know that I hungOn the wind-blasted treeAll of nights nine,Pierced by my spearAnd given to Odin,Myself sacrificed to myselfOn that poleOf which none knowWhere its roots run.No aid I received,Not even a sip from the horn.Peering down,I took up the runes –Screaming I grasped them –Then I fell back from there.[13] And this is where the story begins to turn on itself, becoming a cycle in mythic time, an exercise in simultaneity rather than linearity. For the Hávamál poem is known as, “The Words of the High One”[14], and that high one is Odin, the all father, the sacrificial god. Where he takes the runes from may speak to their origins more fully than any allowable evidence, and may afford a continuity, a connection between the sacred symbols of past civilizations. I would argue that the origins of the runes are neither linguistic or exclusively mythic, but sacred feminine magic, held in the trust-memory of pre-historic, Old European civilizations. Their origins and functions have been long obscured. But in order to parallel the runes with both magic and the sacred feminine, there is another aspect of the tale. This is where I find the runes in my own life, again. Runic Mysteries and Skara Brae I may have arrived faster to the runes had I been more brave. In 1998 I traveled to Europe alone, a pilgrimage to the home of my dead grandfather, Sigurd Rosenlund, in Norway. I was supposed to arrive in London, then take a bus tour through England and Scotland, ending in the Orkney islands where there is a ferry direct to Bergen. But at the last minute I canceled. It was my first time traveling alone. I was twenty-three. I was afraid. Fast forward through linear time: I met my teacher Ingrid Kincaid, who calls herself The Rune Woman, in 2013. Through classes and in-depth gnosis work I developed a powerful relationship with the runes, seeing them as individual beings, in the same way each letter is both a symbol and a sound, each rune is the keeper of information. Last year an art commission from Ingrid drew me to the Orkney Islands again and it is there I found in Skara Brae the evidence I sought linking the runes to a deeper history than the Vikings or the Eddas, the comb or the fibula. Skara Brae is a Neolithic settlement in the Orkney Islands inhabited from 3200 BCE to 2200 BCE.[15] This time frame falls partially within the Old European definition of Gimbutas, though outside of the Old European geographical area typically viewed as southern continental Europe. What drew my attention to this particular complex was the presence of “pre-runic” writing. As I looked closely at the symbols carved at Skara Brae I recognized not just “pre-runic” markings, but runes.  [16] I had the same feeling of revelation when earlier this semester I saw the diagram of Old European script from Gimbutas’ book, Civilizations of the Goddess. Embedded in the ancient symbolic language of Old Europe are the distinct shapes of multiple runes, as well as numerous markings that parallel those at Skara Brae.