Joshua Reynolds's Blog, page 20

March 3, 2021

Nothing for Nothing

It’s in the trees! It’s coming!

– Professor Harrington

Magic always has a price – and someone must pay it. While Julian Karswell never uses those exact words in the 1957’s Night of the Demon, they are nonetheless at the heart of the film. Directed by Jacques Tourneur, starring Dana Andrews, Peggy Cummins, and Niall MacGinnis, the film is based on M. R. James’ seminal story of sorcerous vendetta, “Casting the Runes” and largely follows the same beats. If Dana Andrews’ Holden is a more acerbic protagonist than James’ Dunning, then MacGinnis’ Karswell is far more charismatic figure than his literary namesake.

While the Karswell of James’ story is a reclusive, largely unpleasant academic, the cinematic version is a more boisterous and compelling figure. Here, Karswell is not the sorcerer in his tower, but rather a priest of the faith, delivering miracles to his flock – he pulls back the curtain, returning his audience to the easy beliefs of childhood. He is a salesman, selling the idea of power to the gullible and the faithful alike. This impression is only enhanced by MacGinnis’ performance – by turns oily, charming and menacing, he is the consummate showman, unable to resist any opportunity to display his prowess to an appreciative – or otherwise – audience. And it is this compulsion that proves his eventual undoing.

Karswell is a Faustian figure, equal parts tempter and tempted. He plies his opponents with flattery, hints of secret knowledge, and veiled threats. Those he cannot charm, he attempts to tempt – or frighten. And like the Devil, he saves his best tricks for the most stubborn audiences. Because those tricks are not without cost. One cannot get nothing for nothing. Everything has a price, especially when one traffics with spirits.

It is in his private moments that we see the true Karswell – not the clownish trickster or charming demagogue, but merely a man like any other, frightened of the forces he has conjured and can only barely control. His followers fear, and so too does he. That fear is the price he pays for his power, as MacGinnis so eloquently declaims at one point. Like the storm he summons to impress Holden at the film’s midpoint, Karswell’s magics are easier to call up than to control. His reputed mastery of the dark arts is as much a dodge as his academic qualifications – overblown and illusory.

In the end, that is why Karswell is so desperate to convince others of his power. The more who believe, the more who can pay the price in his stead. Like Maturin’s Melmoth, he collects souls in order to buy back his own – or at least pay down the interest. Unlike his followers, Karswell implicitly understands the true nature of the pact he has made, and what its cost will ultimately be – if not someone else’s life, then his own.

You get nothing for nothing. And once unleashed, the Devil must have his due.

Some things are more easily started, than stopped.

– Julian Karswell

March 1, 2021

Dr. Voronoff of Wych Street

Let’s start the week off right with a few more odds and sods from my commonplace books. This time, its all about non-existent streets, monkey testicles and lost plays.

Wych Street. Decrepit Elizabethan housing, projecting wooden jetties, and the mysterious ‘bookstalls of Wych Street’. Demolished in 1901, but…what if? I think this one stuck in my head just because of the name, likely from the Old English wice, meaning ‘bend’ or somesuch, though you could also draw a link to ‘witch’, for obvious reasons. One street, broken into two and erased. I’m fascinated by the psychogeographic implications of such an act. Wych Street was an edgeland between old London and new, broken apart at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. But what if it was still there, in some form? What if Wych Street, with its strange bookstalls and decrepit houses, was, like its name, bent just out of sight?

Dr. Voronoff and his monkey testicles. This…pretty much speaks for itself, right? Experimental surgery. Monkey testicles. Mad scientist. Monkey testicles. Animal-to-human transplants. C’mon. I shouldn’t have to explain this one.

The Isle of Dogs. 1597 play by Ben Jonson and Thomas Nashe. Performed once and immediately suppressed, for unspecified reasons. A satirical comedy, possibly aimed at the Queen. Players were arrested, homes were raided, and also, stolen jewels were involved, maybe. A lot of weird elements, adding up to a larger, more complex whole. Was it all about politics? Or did it have more to do with a certain stolen diamond? All of the above? Who knows–probably make a good story, though.

February 24, 2021

The Cavalier Occultist

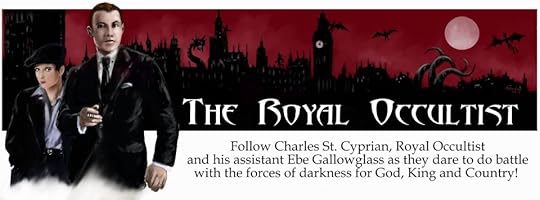

Today’s entry in the Royal Occultist Compendium takes a look at one of the earliest holders of the office – Prince Rupert of the Rhine, 1st Earl of Holderness, Duke of Bavaria, soldier, admiral, scientist, slave-trader and sportsman.

Rupert was the holder of the offices of Royal Occultist during the turbulent period of history known as the English Civil War. It is unknown what incident marked Rupert’s elevation to the office of Royal Occultist not long after his arrival in England, but he soon proved his aptitude for the esoteric during the Affair of the Buckinghamshire Devil in 1642.

With the broken remains of the eponymous devil buried beneath an innocuous field, Rupert set about proving his worth as both a military commander and the Queen’s Conjurer. However, his career as Royal Occultist was fraught, to say the least. The civil war was a period of mass chaos, marked by witchcraft and necromancy on an unprecedented scale as dark forces sought to take advantage of the troubles.

From the renegade alchemist O’Neill to the degenerate d’Amptons of Derbyshire, Rupert’s opponents were too numerous to properly record. Even so, he managed to assemble one of the largest occult libraries in the Occident, as well as a not inconsiderable arsenal of mystical artefacts over the course of his tenure, and he is known to have developed and refined a number of rituals still used by the holder of the offices to this day.

Despite this, his conduct during his tenure was not without blemish – Rupert was not above attempting to turn the horrors he faced to his own advantage, such as his attempt to bind the monstrous Knights of St. George to the Royalist cause or his association with a certain mysterious ‘Lapland lady’, who often accompanied him on his investigations in the shape of a white dog.

Indeed, Rupert is known to have used vile sorceries against the King’s enemies on no less than two occasions, and is rumoured to have made an attempt on Oliver Cromwell’s life through mystic means.

Rupert was stripped of the offices in 1655, and soon after, his quarrels with the Royalist court-in-exile sent him to the Germanies, where he is known to have consulted with a certain Baron Vordenburg of Styria on the matter of the Devil Ferenczy, as well as the Circus of Night. He re-assumed the post briefly in 1660 following the Restoration in order to combat the machinations of the Kind Folk, but, weary and disinterested, soon stepped aside, in favour of his former apprentice, the aptly-named John Cadmus.

Like Dee, Rupert’s influence is strongly felt throughout the series, despite only appearing in a single short story (“Scholar’s Fire”) thus far. He’s one among a number of historical personages that I tapped early on to be former holders of the office of Royal Occultist. I thought that by interweaving real and imaginary people, I could give the stories a bit of grounding.

Too, Rupert, like John Dee, is interesting in and of himself. Scientist, artist, statesman…Rupert was a Renaissance man in the truest sense of the word. Though like many such individuals, Rupert had his dark side – his participation in the slave trade, for instance. While his willingness to use black magic against his enemies is something I added, I feel it’s in keeping with Rupert’s character, especially after his return to England during the Restoration. A battered Rupert, weary, sick in body and soul, makes for almost as interesting a Royal Occultist as the dashing young cavalier. Especially when you add the taciturn John Cadmus into the mix.

I envisage the Rupert/Cadmus relationship as a bit like that of Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe, albeit with more sinister overtones. I’d like to write more stories with the two – that period of history is full of interesting nooks and crannies to explore.

If you’re interested in learning more about Rupert, I recommend Charles Spencer’s book, Prince Rupert: The Last Cavalier (2007).

If you’d like to check out some of the Royal Occultist stories for free, head over to my Curious Fictions page. For more general updates, be sure to check the Royal Occultist Facebook page.

February 7, 2021

The Phantom Fighter

“Tomorrow is another day, and who knows what new task lies before us?”

– Jules de Grandin

‘He was…rather under medium height, but with military erectness of carriage that made him seem several inches taller than he actually was. His light blue eyes were small and exceedingly deep set and would have been humorous had it not been for the curiously cold directness of their gaze. With his blonde moustache waxed at the ends in two perfectly horizontal points and those twinkling, stock taking eyes, he reminded me of an alert tom-cat.’

Such is the stout Dr. Trowbridge’s description of Jules de Grandin, late of Paris, the Surete and the Sorbonne, upon first meeting the irascible little French physician in the 1925 story, “Terror on the Links”. Cat-eyed and ebullient, de Grandin is the epitome of the phrase ‘it’s not the size of the dog in the fight, but the size of the fight in the dog’. He defends Harrisonville, New Jersey, and by extension, all of mankind, against the spawn of Satan, using forbidden knowledge and firearms alike.

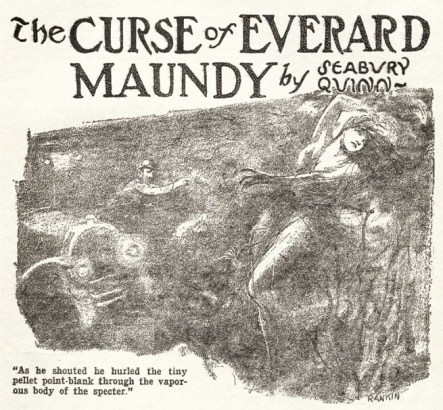

Jules de Grandin and his ever-present companion, Dr. Trowbridge, were created in 1925 by Seabury Quinn for Weird Tales and went on to feature in close to a hundred stories, with the last, “The Ring of Bastet”, appearing in 1951. Quinn, in the introduction to the 1976 Popular Library collection, The Adventures of Jules de Grandin, says that de Grandin is ‘…a sort of literary combination of Topsy and Minerva, that is, he just growed.’

It’s hard to imagine it being otherwise, given the sheer vibrancy of de Grandin from the start. De Grandin, like his more passive predecessor Dr. Hesselius, is a physician, and approaches the supernatural as an illness to be confronted. Unlike the kindly Hesselius, however, de Grandin is no amiable general practitioner, but a surgeon—flamboyant, precise and ruthless.

While characters like Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence, or William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki might be considered the archetypal occult detectives of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, then de Grandin is, perhaps, the primogenitor of those who came after.

In de Grandin one can see the antecedent of such later two-fisted occultists as John Thunstone, Anton Zarnak and Titus Crow. Thunstone, created by Quinn’s contemporary (and friend) Manly Wade Wellman, often cameos in the de Grandin stories and vice-versa. The stories themselves, told from the perspective of the redoubtable Dr. Trowbridge, owe more than a nod to Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, with Trowbridge being a less perspicacious stand-in for Watson. De Grandin himself, however, is less Holmes than Agatha Christie’s clever Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot, given a pulp hero’s sheen.

De Grandin is an active fighter of evil. He is a hunter of monsters, a buster of ghosts and a banisher of eldritch entities of all stripes and persuasions. Indeed, given what hints de Grandin drops as to his lineage, it might be that he was simply pursuing the family business.

But not all of de Grandin’s opponents were of the supernatural variety—many were of a more human persuasion, though no less vile than the ghoulish Monsieur and Madame Bera of “The Children of Ubasti” (1929) or the vampiric Baron Czuczron of “The Man Who Cast No Shadow” (1927) for all that they were men, rather than monsters. For instance, in “The Isle of Missing Ships” (1926), de Grandin and Trowbridge battle a murderous pirate with a penchant for feeding his victims to a giant cephalopod.

In “The Great God Pan” (1926), the duo confronts the leader of a sinister sylvan cult. And, in the horrific “The House of Horror” (1926), de Grandin discovers the lair of mad surgeon, and the pitiful mewling things he’s made of his victims. Svengalis, trained snakes and cultists abound in the ninety-odd stories, appearing just as much as werewolves, vampires, and witches. There were also any number of science-fictional antagonists—the ape-man of “Terror on the Links”, for example or the eponymous psychic of “The Brain-Thief” (1930).

Given his wide variety of foes it should come as no surprise that while other occult investigators relied on hoary Atlantean wisdoms, magical blades or the blessings of benevolent gods, de Grandin put more faith in a well-oiled automatic and a professional psychological or physical diagnosis. What bullets don’t put down, blades would, or topical ointments or electricity or even, in the case of the aforementioned giant cephalopod, poison. But the most potent weapon in de Grandin’s arsenal is perhaps is his chilling ruthlessness.

He is not above using the innocent to draw out whatever beast he is stalking, as he does in “The Children of Ubasti”, when he convinces a young woman into acting as bait for a pair of rapacious ghouls, or in simply gutting a helpless enemy, as he does to the human antagonist of “The Isle of Missing Ships”.

There is little doubt that that ruthlessness served de Grandin well. Unlike the dour John Kirowan or the unfortunate Laban Shrewsbury, de Grandin never met an enemy he could not out-think, out-fight or simply out-gun. His propensity for simply obliterating the supernatural menaces he faced made him a name to conjure with, in occult investigative circles. It is hard to imagine de Grandin coming up against an enemy, no matter how vile, that he could not handily defeat. But even if he did, there is no doubt that Jules de Grandin would face that foe nonetheless, with a twinkle in his eye and an automatic pistol in his hand.

While the stories can become formulaic, there’s no mistaking the sheer, unbridled enthusiasm that they were written with. Seabury Quinn was the most popular contributor to Weird Tales in his time, handily beating out such luminaries as HP Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, and the Jules de Grandin stories are, in large part, the reason for that.

While hard to find for many years, the de Grandin stories have recently come back into print thanks to Night Shade Books, in both hardback and digital format. All of the stories are now available, and I highly encourage you to try out at least the first volume.

*Author’s Note: This essay originally appeared in 2011, at Black Gate Magazine.*

January 22, 2021

Fierce, Cruel and Deadly

…expect something that’s fiercer, more cruel and deadly than anything that ever walked the earth.

– Professor Townsend

A severely deformed man stumbles through the desert. Falls. Dies. But that is only the beginning, as the tiny Arizona town of Desert Rock is soon besieged by a horror unlike any other. So begins the 1955 big bug classic, Tarantula.

It’s one of the better giant-insect films, both in terms of production and acting. It’s also one of my favourites, along with Them! (1954) and The Black Scorpion (1957). The special effects are fairly advanced for the time, and the opening sequence with its stumbling, irradiated victim in his striped pyjamas, is darkly effective for a number of reasons. John Agar does his usual workmanlike job as square-jawed leading man. Jack Arnold, the director, was responsible for a few other favourites of mine, including Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954).

Unlike the Lovecraftian overtones of the former, however, Tarantula is, at its core, a Promethean fable for the Atomic Age. The eponymous monstrosity is neither fish nor fowl, to mangle an old saying. It isn’t an outsider trying to get in, nor is it something ancient imposing itself on the modern era.

Even so, there is a whiff of the eldritch to its creation. Radiation and strange chemicals might as well be the tools of necromancy as far as these sorts of films go. The tarantula is summoned like Karswell’s demon, and loosed upon the Earth when its ritual (re: atomic) bindings falter. An unfettered devil, running riot.

It is a child of Frankenstein – in spirit, if not blood. Even as Frankenstein’s monster was born out of an attempt to defeat death, the tarantula’s apotheosis has its origin in an experiment meant to help mankind. It is made into what it is through modern alchemy, and loosed upon the world thanks to the hubris of its creator. But unlike the monster of Frankenstein, the tarantula is no tormented child turned wicked.

Instead, the beast is a disaster made flesh, a hunting horror predating upon an unsuspecting populace. It is not evil, for it is beyond such things. If anything, that only makes it more terrifying. Like the ants of 1954’s Them!, the tarantula is an inhuman intelligence in its purest form. A thing that cannot be bargained with, intimidated or tricked. Remorseless and savage, it hunts as it was designed to do – both by evolution and the atomic alchemist who made it into something monstrous.

As it stalks its prey beneath the desert sun, the tarantula is nothing less than an atomic nemesis, giving us our due in payment for the sin of hubris – it is a walking bomb, bringing destruction wherever its shadow falls. And even its demise brings no true comfort, for the terrible forces which created it still exist, hanging over the heads of the survivors.

Even as they exist today.

I think I’ve had enough of the unknown for one afternoon.

– Stephanie Clayton

January 15, 2021

The Brazen Head of Frankenstein

In lieu of real content, have a few random assortments from my commonplace book. Automatons, Italian cinema and a grimoire. All the ingredients for an interesting weekend.

Brazen heads. Mechanical or magical automaton. Answers any question put to it, albeit in a ‘yes or no’ sort of way. Connected to alchemy and occultism. Also, ‘the Skull of Balsamo’ is too good not to use in some fashion. Either as a title or a macguffin. Possibly a Royal Occultist story.

The Monster of Frankenstein. Il Mostro di Frankenstein. 1920s Italian silent horror film. Lost film. Very little is known about it, though I fully expect someone to show up in the comments and say otherwise. This is one of those things that I really, really want to do something with, but for the life of me, can’t figure out what. Is it the germ of a Royal Occultist story? A ghost story? I’ll figure it out eventually.

The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses. Grimoires. I do love grimoires. Especially ones used by Moses to defeat the magicians of Egypt. And ones mentioned in Manly Wade Wellman stories. These things are like multi-tools. Good for any sort of story, really.

January 5, 2021

The Black Pharaoh

Permit not thou to come nigh unto me him that would attack me in the House of Darkness.

-Book of Dead

Nephren Ka. The name of an old horror from a forgotten time. Little is known of the being known as the Black Pharaoh. Scattered references in ancient writings were all that remained to mark the existence of a creature intentionally obscured from history.

Obscured, that is, until the year 1919, when occultist Edward Bellingham and his Esoteric Order of Thoth-Ra discovered the long-hidden tomb of the Black Pharaoh and brought him back to London. During a ghastly unwrapping ceremony, the monster was freed from his ancient prison. Luckily, the Royal Occultist was on hand to return the savage mummy to the sleep of ages.

Or so he thought.

Nephren Ka returned again and again to bedevil St. Cyprian and Gallowglass. Each time,the mummy returned, stronger and more cunning than before. The creature even found allies in the ancient cults that served the same dark gods as Nephren Ka had in life. But each time, St. Cyprian and Gallowglass managed – if barely – to seemingly destroy the creature through fire and sorcery. Only time will tell if his most recent return was also, finally, his last.

I love mummy movies – like The Mummy’s Hand, or The Mummy’s Curse – and mummy stories – like Conan Doyle’s “Lot No. 249”, Charles L. Grant’s The Long Night of the Grave, Lin Carter’s “Curse of the Black Pharaoh”, or Steve Duffy’s “The Night Comes On” – so it’s probably no surprise that I’d try to wedge one (or several) into the Royal Occultist series.

There’s something about a mummy that just fits the 1920’s horror aesthetic. Interest in Egyptology and occultism were growing in the West, and the idea of an ancient terror wandering the foggy streets of London is a potent one. I’ve gone to that particular well numerous times – probably too many – but it’s hard to resist.

Appropriately, Nephren Ka has proved to be one of my most enduring villains. Like the Hound, he’s an homage to the old monster movies I enjoyed as a kid. And like them, he returns again and again, each time worse than before. But while he’s not the only mummy to appear in the Royal Occultist stories (did I mention that I like mummies?), he is the most dangerous.

I’d love to make Nephren Ka a reoccurring foe for future Royal Occultists, having him pop up in the Fifties, the Seventies and so on, being brought back to un-life by cults, mad scientists and the like. For some reason, I’ve got this image of a crumbling mummy tearing apart Piccadilly Circus stuck in my head.

If you’d like to check out some of the Royal Occultist stories for free, head over to my Curious Fictions page. For more general updates, be sure to check the Royal Occultist Facebook page.

January 3, 2021

The Ghost Seer

Does a night like this fill you with vague longings? Do you yearn to discover the secret of the universe-to know more than is good for man to know-perhaps to peer into the future?

– Aylmer Vance

Aylmer Vance made his first appearance on the nightmare stage in 1914. The creation of husband-and-wife writing team Alice and Claude Askew, Vance appeared in eight consecutive issues of The Weekly Tale-Teller between July and August.

The stories ranged from grotesque to gentle, and are, by and large, of a slower pace than those featuring Vance’s contemporaries, such as Carnacki. Only one of the stories has been regularly anthologized (“The Vampire”), with the rest languishing in obscurity until the release of recent collections by Ash-Tree Press and Wordsworth Editions respectively.

Like John Silence, Vance inhabits an England of soft spiritual influence, where elementals, ancient memories and ghostly manifestations cling to the unseen corners and visit just long enough to inject the mundane with a booster shot of the strange. The apparitions that Vance faces are utterly human in their aspect, if not their motivation. Death is no barrier to the desires of the flesh or the dreams of the determined, and it is when these elements intrude on the hard-won peace of the Edwardian mind that the Ghost-Seer must intervene.

The majority of the Vance stories are told at a remove, with Vance himself narrating these tales after the fact to his companion, Dexter. A humble barrister, Dexter provides an identifiable viewpoint character for the reader. However, he does manage to get in on the action once or twice, most notably in “The Vampire”, where he is instrumental in rescuing an innocent victim of the eponymous monster.

Vance is often late to the party when occult oddities rear their head, unable to effect a solution or worse, inadvertently causing the very misfortune he sought to prevent. In “The Invader”, for instance, his efforts lead to the death of a friend and the spiritual disembodiment of the man’s unfortunate wife. And in “The Fear”, Vance can only recommend the absolute destruction of the client’s castle in order to quell the haunting – a favourite method of ending spectral threats in the Vance stories.

Indeed, compared to a character like the dynamic Shiela Crerar, poor Vance is a bit of a wet noodle when it comes to the occult. He shows all the knowledge of a dedicated opponent of the more malevolent forces of the supernatural world, but displays a distinct lack of gumption. The only exception to this is in “The Vampire”, where Vance functions as a traditional occult detective, puzzling out the gruesome mystery to a man’s recurrent anaemia, and effectively ending the threat of the blood-sucker in question.

There’s a strange sort of fragility to the character of Vance. A tenderness that brings tears to his eyes when he recounts the sad fate of the doomed couple in “The Invader” or the determined final walk of the young would-be bride in “The Indissoluble Bond”. Other, contemporary, occult investigators display a gruff professionalism in their business. They are sympathetic, but not so empathic to the almost embarrassing degree that Vance displays.

Indeed, Vance is less an investigator than an apologist in some respects. He treats supernatural beings as a naturalist might treat wild animals, seeing them not as opponents, but as fascinating subjects of study and wonder. That they become involved in the business of humans is, to Vance, a distressing prospect.

Such softness of outlook might be explained by the events of “Lady Green-Sleeves”, where Vance’s first (and only) true love is revealed – perhaps unsurprisingly – to have been a ghost. Regardless of its origins, this softness of spirit hampers his abilities as an occult investigator.

Vance is more apt to throw himself down on a bed of rushes and watch the majestic spin of the stars in the night sky than he is to face down a hungry horror from beyond the veil. Indeed, in at least two cases (“The Stranger”, and “The Fire Unquenchable”), he withholds his knowledge and aid from the afflicted in order to facilitate the desires of the supernatural entities in question.

Still, despite being largely ineffective and occasionally downright unhelpful, Vance does his best to try and aid those he deems to be truly in danger. The ever-faithful Dexter at his side, he offers gentle counsel and advice, trying his best to steer his clients, friends and companions out of the murky, dangerous waters of the occult world. He faces the creeping fear of Camplin Castle and the blood-thirsty horror of Blackwick with neither hesitation nor recrimination.

There is more to this dichotomy, perhaps, than weak characterization. Vance displays a similar otherworldliness to John Silence, acting as if he is privy to secret things which colour his judgement in certain moments; a superior sense of the spiritual, which forces him to act not just as protector, but as mediator and facilitator. A keeper of some esoteric balance which is visible to none but Vance himself.

Perhaps the Ghost-Seer simply knows more than he’s telling.

*Author’s Note: This essay originally appeared in 2011, at Black Gate Magazine.*

December 31, 2020

2020 in Review

What to say about this year that other, better writers have not already said? Still, I might as well try. Like most, it’s been a year of ups and downs for me, professionally and otherwise. A professional partnership ended unexpectedly, but new opportunities arose and my career continued on much as it has for the past decade. I managed to write two books, despite (gestures vaguely at the world) everything, as well as a handful of short stories. I had four books on the shelves this year. I made some new contacts, got some new contracts, did some interviews and had some revelations.

I did some soul-searching as well, concerning my continuing issues with work/life balance. Anyone who’s been following me for any length of time knows that I’m a workaholic – an addict of productivity. If I’m not working I tend to…wind down. When I am working, I vanish into my own head for days at a time.

This issue has hounded me for a long time – since I got my first job. I live to work, and work to live. I work even when I’m supposed to be on vacation. If we’ve ever talked in person, rest assured that I was almost certainly writing something in my head at the same time. I write when I’m awake, when I’m asleep, while eating. I don’t know how to relax – never have.

It’s not a healthy way to live, and though I’ve made some improvements in regards to exercise and food – for instance, I’ve lost around twenty pounds this year, putting me at the slimmest I’ve been, well, ever – I still tend to get too wrapped up in work to function like anything approaching a normal human being.

I know that authors I admire have had similar problems, resulting substance abuse issues, failed marriages and worse – bleeding onto the page is a common cause of death, in this profession. Thankfully, I have no intention of following their examples. One of the reasons I changed the way I approached this blog was due to these issues. I also scaled back my professional writing this year, turning down a number of opportunities I might otherwise have jumped at, in order to spend more time with my family. I intend to do the same going forward into 2021. Or at least I intend to try.

A new year, a fresh start. But the same old hounds are on my trail. They always will be. But the distance between us is growing.

December 28, 2020

Invisible Empire

“An invisible man can rule the world. Nobody will see him come, nobody will see him go. He can hear every secret. He can rob, and rape, and kill!”

-Dr. Jack Griffin

The Invisible Man first hit theatres on the 13th of November, 1933. Directed by James Whale, starring Claude Rains and Gloria Stuart, based on the 1897 novel by H.G. Wells. Like many of Whale’s films, it has a strong undercurrent of absurdist humour, which only serves to amplify the horror. Too, Whale allows the characters to guide the plot, rather than the reverse. While the structure of Wells’ novel is there, Whale and screenwriter R.C. Sherriff breathe a raw vitality into the characters that is otherwise lacking in the source material.

It’s one of my favourites, for a lot of reasons. The humour, for one. Whale delighted in injecting the absurd into the horrible – brief moments of the ridiculous, to leaven the darkness. Praetorius’ mausoleum picnic, or Una O’Connor, shrieking forever, into a void, for instance. The Invisible Man could be considered the ancestor of such ghoulish comedians as Freddy Krueger, mocking his victims with a dry wit, even as he throttles them. He laughs, he chortles, he capers – he’s having fun, you see. It sets him apart from Larry Talbot’s dolorous moaning or Dracula’s arrogant pomposity, though he’s no less deadly than his fellow Universal Horrors.

Rains’ Dr. Jack Griffin is manic monster, alternating between oily menace and brutal savagery, save when confronted by his fiancee, Flora, as played by Stuart. In those moments, Griffin’s natural decency shines through – here is the man he was, the man he should be. Inevitably, however, those moments of lucidity crumble, leaving behind a ruin of a human being, rotten with hatred and desire.

As with later horrors, Griffin is no supernatural menace, arising from antiquity. Instead, he is a scientific abomination, a thing of test tubes and beakers, rather than tombs and gypsy curses. But like Frankenstein’s creation, there is an element of the eldritch to him – monocane might as well be an alchemical concoction, after all, and its effects are as much magical as they are scientific. As his affliction progresses, Griffin descends into monstrosity, as if being rendered invisible has given him license to revel in every secret thought and ugly desire that afflicts mankind.

And it is a revel. Griffin’s rampage through Sussex is positively bacchanalian. A drunken riot – violent, noisy, and humiliating. He engages in lewd behaviour and spiteful acts, amidst the more mundane carnage. Unlike the Wolfman, Griffin is in this for the giggles. He relishes the power that comes with his new abilities, even as he loses his grip on his humanity.

Griffin’s later murderous rampage is made all the more horrific by the tattered remnants of that very humanity. He is no golem of dead flesh, or blood-drinking night walker, seeking victims out of anger or to satisfy an unholy need. Instead, he is simply a man, with a man’s strength and a man’s cunning, but cursed with a freedom no man has ever known. His crimes are a man’s crimes, committed for the deranged joy of it. He wishes to crash trains and murder great men, because he wants to be feared.

Griffin is a maniac who becomes a monster, thanks to his invisibility.

Worse, he is a man who becomes a maniac, thanks to an accident.

And that is the true horror of Griffin’s story. That, under the right (or wrong) influence, anyone might lose all sense of self, and become someone else. Someone relentless and predatory, capable of anything.

A monster.

“Here I am. Aren’t you pleased you found me?”

– Dr. Jack Griffin