Joshua Reynolds's Blog, page 19

August 14, 2021

Marceline, Marceline

I read a thing, not long ago, and it got me to thinking, and making notes for a story I’ll probably never write. I do that a lot. Ideas, and the notes that come with them, are a dime a dozen. I get five ideas before breakfast and five more after my first cup of coffee. Ideas are cheap. Time is expensive.

Anyway, “Medusa’s Coil”, by H.P. Lovecraft and Zealia Bishop. Like “The Horror at Red Hook”, I both enjoy and detest this story. It is, without a doubt, one of the most staggeringly, ridiculously, obtusely racist stories Lovecraft ever attached his name to. The denouement alone is infamous…

It would be too hideous if they knew that the one-time heiress of Riverside—the accursed gorgon or lamia whose hateful crinkly coil of serpent-hair must even now be brooding and twining vampirically around an artist’s skeleton in a lime-packed grave beneath a charred foundation—was faintly, subtly, yet to the eyes of genius unmistakably the scion of Zimbabwe’s most primal grovellers. No wonder she owned a link with that old witch-woman Sophonisba—for, though in deceitfully slight proportion, Marceline was a negress.

– Medusa’s Coil (1939)

C’mon, dude. At least try and be subtle about it.

Rereading the story, I was struck by the thought that the whole narrative might be topsy-turvy. Antoine de Russy is the epitome of the unreliable narrator, as are his son, Denis, and the painter, Frank Marsh. The picture they paint of Marceline Bedard (pun intended) is one overwhelmingly tainted by bigotry, misogyny and jealousy. And even then, her on-screen crimes amount to…falling in love with an idiot, being a bit shallow, showing interest in the wrong men, and, well, being not-white. As far as eldritch horrors go, she’s not exactly scary, is she? Other than the thing with the hair, I mean. Even that’s more ‘Lady, you come right out of a comic book‘ than, y’know, evil.

Too, Marceline is far more interesting a character than the nominal protagonists of the story. Where did she come from? How did she come to acquire the occult knowledge she possesses? Or control a group of mystics in Paris? What’s the deal with that hair? What’s her connection to R’lyeh and Cthulhu, if any? Did she ever meet Harley Warren, or Randolph Carter? What about Charles Dexter Ward or Nathaniel Wingate Peaslee?

Questions, people. I have them.

For me, “Medusa’s Coil” is a story in need of, if not reclamation, then at least some reinterpretation. Especially the ending. Marceline Bedard is too intriguing a character to wind up on the wrong end of a machete and buried in quicklime. At least, not permanently. But physical death isn’t the end, in Lovecraft’s universe. It’s often just a gateway, to a stranger, bolder existence. Randolph Carter found that out. And King Kuranes. Probably better not to mention poor Edward Derby.

What if Marceline escaped to somewhere else? What if the gorgon-haired adventuress stalks a new and more interesting world, with new dangers?

What if.

Like I said, notes for a story I might never write.

July 14, 2021

The French Connection

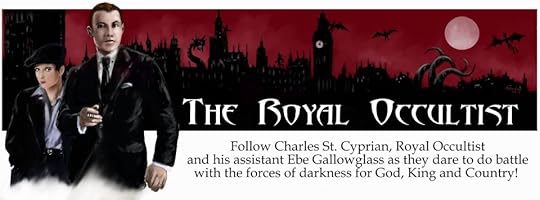

Today’s look at the world of the Royal Occultist features on another ally of Charles St. Cyprian, the so-called Necromancer of Paris, Andre du Nord.

Andre du Nord is the latest in a proud Gallic line of sorcerers, occultists and necromancers. The du Nords have owned land in the werewolf-haunted province of Averoigne since 1281 and they are one of the Heritiers de la Sorcellerie–the great sorcerous bloodlines of France–along with the de Marignys and the d’Erlettes, among others.

Though sorcery was in his blood, du Nord nonetheless required training. In his youth, he studied at the feet of a number of teachers, including the infamous Claude Mambres and the Flemish warlock, Quentin Moretus Cassave. It was while studying under Mambres that Andre first acquired the sobriquet, ‘Necromancer of Paris’ – a title he views more as burden than honour.

St. Cyprian and du Nord first met in Averoigne in 1913, not long after the former had become Thomas Carnacki’s apprentice and the latter had completed his own training in the necromantic arts. Later that year, the two men would participate in the 1913 Grand Prix, where they ran afoul of a rogue patisserie in Amiens. Their friendship survived this rocky start and flourished in the following years.

Since that time, du Nord has aided St. Cyprian in a number of cases, including the Carpathian Repatriation of 1920 and the ‘Immacolata Abominata’ incident in July of the following year. St. Cyprian has returned the favour numerous times, joining du Nord in his own investigations into the abnatural on behalf of the Parisian police, as well as the various governmental agencies that make use of du Nord’s talents. Together, the two men would apprehend the villainous Doctor Lerne and counter the monstrous schemes of the Count of Saint-Germaine.

A loner by circumstance, du Nord would eventually find an assistant in the former Tirailleur, Yusuf Ba. Together, the two men would confront demonic cats, forgotten goddesses and horrors from the stars in the years leading up to the Second World War.

Andre du Nord, like Baron Vordenburg, is one of the Royal Occultist’s international peers. And also like Vordenburg, he has a notable literary antecedent – Gaspard du Nord, the protagonist of Clark Ashton Smith’s short story, “The Colossus of Ylourgne”.

Observant readers will note that this isn’t the first time that I’ve mined that particular story for my own benefit – Ylourgne, and the alchemical experiments of the dwarfish necromancer Nathaire, are mentioned in another Royal Occultist story, “Dead Men’s Bones”. Given that “The Colossus…” is one of my favourite CAS tales, this is perhaps unsurprising.

I originally created du Nord as a means to give St. Cyprian a contact in Paris in the novel Infernal Express (now being serialised over at Curious Fictions, if you’re interested), and while his page time was limited, I grew to like him. On the surface, he’s quite a similar character, but there are enough differences there to make him interesting, I think.

Though I initially had no plans to spin du Nord off into his own stories, I’ve since had a change of heart and completed the first of what I hope will be many tales featuring du Nord and his assistant, Yusuf Ba. France is rife with fodder for occult detective stories, from the Court of Miracles to the Beast of Gevaudan. Like Vordenburg, I think he’s a character with a lot of potential, and I hope to be able to explore it in the future.

If you’d like to check out some of the Royal Occultist stories for free, head over to my Curious Fictions page. For more general updates, be sure to check the Royal Occultist Facebook page.

June 24, 2021

A Hard World for Little Things

Salvation is a last minute business, boy.

– Rev. Harry Powell

It’s a hard world for little things.

No film captures the truth of that statement better than Charles Laughton’s 1955 thriller, The Night of the Hunter. Starring Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters and Lillian Girsh, its a brutal film – a dark fairy tale, at once old fashioned and ahead of its time.

Mitchum’s Reverend Harry Powell, with his tattooed knuckles and mouthful of scripture is a murderous grifter – a travelling man, who preys on the little things…the innocent, the naïve, the gullible. Powell is a wolf in shepherd’s clothing, and he views his flock only as meat for the beast. Superficially charming, but with an edge that only adds to his compelling personality, Powell is a dark force that descends suddenly on his victims, with no warning, taking what he wants and justifying it as the will of God.

There is a rawness to Mitchum’s performance as Powell – a sort of earthy ferocity that drives the character forward through his every moment of screen-time. Powell is erudite, but not wise. Cunning, but not intelligent. He is a thing of cruel lusts and needs, but cagey enough to hide that side of himself from those not directly in his sights. Even so, something of his true self simmers in his voice, his eyes, the way he walks. The way his hands clench around themselves as he discusses his tattoos hint that he wants nothing more than to throttle the world – to break it to his will.

For all his outward piety, there is a monster under Powell’s skin. And it takes only a little pressure for it to rip its way free. He marries Shelley Winters’ Willa, seeking the money her husband hid away, but he cannot resist toying with her – indulging his instincts before finally doing away with his unassuming bride. Her children, wiser by far, flee into the night before he can do the same to them and he pursues like some ogre out of a fairy tale.

And there is much of the fairy tale about that pursuit. Laughton’s choice to emulate the German expressionistic films of previous decades only adds to this dreamlike quality, making it a sequence of long shadows and broken moments. As the children flee down the river, Powell follows, his voice haunting their trail. The good reverend is a direct forebear to later implacable monsters such as Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees, with a wit and wickedness to match Freddy Kruger. His relentless pursuit of the children is equal parts mythic and nightmarish – a wild hunt, though one pared to the symbolic bone. Something wild and inimical, in pursuit of the undeserving innocent. Wherever the children go, however far they flee, their tormentor is always there in the distance, drawing nearer with every passing moment, singing his mocking hymns.

But like all monsters, Powell has his nemesis. A force of good to match his evil, the sister love to his brother hate, the spinster Rachel Cooper, played by Lillian Girsh. And when the two collide, it is Powell who finds himself the hunted, before he is at last brought to bay and finally captured for his crimes. Cooper is the Van Helsing to Powell’s Dracula – a woman wise to the ways of the Harry Powell’s of the world, and capable of flinging his own pious darts back at him, of matching him hymn for hymn. It is their struggle for the souls of the children which dominates the climax of the film, and sees Powell’s inner monster rage forth with a wild, yelping screech. But Cooper does not flinch, and in the end, Powell is done in by his own savagery and impatience.

Yet Powell is no more diminished in defeat than Dracula or Frankenstein’s creation. He has made his mark, done his damage and though the world – and his victims – will eventually heal, the film makes clear that the shadow of Harry Powell will forever stalk them. His memory will linger on, well past the date of his demise.

But there is hope. Powell’s memory lingers, but so too does the kindness of his nemesis, Cooper. And the latter may well prove the stronger.

It’s a hard world for little things. But they abide and endure.

There’s too many of them. I can’t kill the world.

-Rev. Harry Powell

June 12, 2021

The Westenra Fund

A body drained of blood is found on Hampstead Heath. Three nights later, a white face is seen pressed against a window in Highgate. In Hampstead tube station, something titters in the shadows of the platform. In Surrey, a phone rings.

The agents of the Westenra Fund are on the case…

The origins of the organization known as the Westenra Fund are traceable to an incident in Purfleet, in 1889. A disparate group of men and women banded together to defeat one of the greatest evils to ever assail the shores of England. In the aftermath, the survivors swore an oath to defend their homeland from the scourge of vampirism.

Unlike the Ministry of Esoteric Observation or the office of the Royal Occultist, the Westenra Fund is a privately funded organisation, with only tenuous links to the British government. While this is mostly by choice, it is also due in no small part to the Fund’s proclivity for excessive collateral damage in pursuing their singular calling – the destruction of the sanguinary vermin known as vampires.

While the last English vampire was reported destroyed in 1908, the Fund has maintained its vigilance against the undead. It has even conducted international operations alongside the Calmet Society and other anti-vampire organisations, in Europe, Latin America and Canada.

The current head of operations for the Westenra Fund is also one of its main financial backers – Sir Arthur Holmwood, Lord Godalming. Godalming is an elderly, but still vigorous man who often insists on leading domestic operations himself. Foreign operations are often left to the mysterious Miss Harker, an unusually pale young woman of unsettling demeanour.

The history of the woman known variously as Miss Harker, (or, variously, as ‘Lady Godalming’, ‘Lucy Harker’, ‘the bloofer lady’ and ‘oh god oh Jesus it’s her run’) is shrouded in half-truths and mystery. Which is just the way she likes it.

The daughter of a solicitor and a school mistress, but the child of a monster, Harker was born with certain unnatural gifts. These gifts – as well as her fierce loyalty to Godalming – saw her swiftly become the most invaluable member of the Westenra Fund. To date, Harker has seen to the destruction of over thirty vampires, five at her own hands.

It was in her capacity as head of the Fund’s foreign operations division that she first encountered Charles St. Cyprian and Ebe Gallowglass. First forced to work alongside them during the Carpathian Repatriation of 1920, Harker and the Westenra Fund have since consulted with the Royal Occultist on numerous occasions. Godalming has also reportedly attempted to contact Baron Palman Vordenburg, but, as yet, the Baron has avoided meeting with the Fund’s representatives.

The Westenra Fund, like the Ministry of Esoteric Observation and the London Tunnel Authority, was created as something of a combination foil and plot generator for the Royal Occultist series. And of course, if you’re going to talk about the British Empire and vampires, you can’t really avoid a Dracula reference.

As always, when confronted by such a quandary, I tend to lean into the skid. Using Stoker’s novel as a starting point, I wove it into the fabric of the Royal Occultist series – the events of Dracula occurred, but not necessarily as written. For one thing, the then-Royal Occultist, Sir Edwin Drood, was involved, and there were more casualties. Dracula’s assault on England didn’t begin and end with one small group of Victorians, but rather was a pestilence that endangered London as a whole.

I doubt I’ll ever actually write about it in any detail. It’s probably better to leave it as a noodle incident – often mentioned but never fully explained.

That said, Lucy Harker is a fun character – conceived as an homage to various pop culture vampire slayers, she very quickly diverged into something interesting. If I ever have the time and inclination, I might even try and spin her off into her own stories. I think she’s a strong enough character to have a life of her own outside of occasional guest appearances.

Another note of interest – Harker and the Westenra Fund both first appeared in my now long out of print 2010 novel, Dracula Lives!. Though it’s debatable whether that novel exists in the same continuity as the Royal Occultist stories, Harker and the Westenra Fund are pretty much the same characters in both. But I’ll leave that up to readers to decide whether there’s a canonical connection.

If you’d like to check out some of the Royal Occultist stories for free, head over to my Curious Fictions page. For more general updates, be sure to check the Royal Occultist Facebook page.

May 21, 2021

Manly and Me

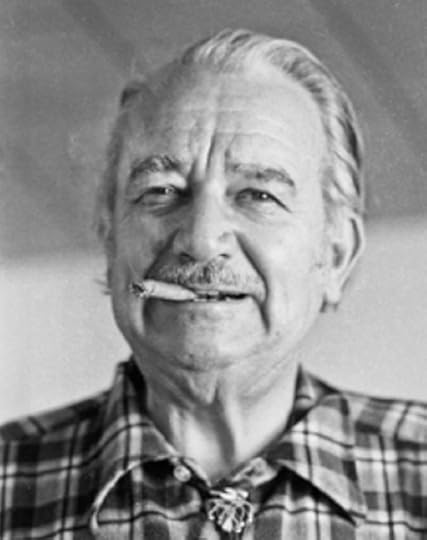

It’s Manly Wade Wellman’s birthday, and I want to talk about him.

Have you ever read Manly Wade Wellman? You’d remember if you had. His stories ran the gamut from science-fiction to horror, and the latter were, as the man said, a bit Johnny Cash meets the Cthulhu Mythos. He wrote about Sherlock Holmes and Professor Challenger fighting the Martians and about warrior-queens in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mostly, he wrote about the mountains, and the people who lived in them. And he did it well.

He influenced authors like Karl Edward Wagner and David Drake, as well as artists, musicians and a host of others, including film-makers. He influenced me, too. The first stories I ever wrote were Manly Wade Wellman pastiches. A lot of writers in the speculative fiction game start off with Lovecraft or even Howard, but I went straight at the big dog. The guy who wrote like I talked. He wasn’t some big-mouth Texan with a Celt fixation or the crazy-racist Yankee with a thing about fish and geometry.

No, he was a stand-up guy. Prolific, too. In those first few months of discovering him, it seemed like I could read and read and never run out of stories about John Thunstone, Judge Pursuivant and John the Balladeer. But I did. Luckily, there were enough that I could start over fresh when the time came and re-read them.

Everyone’s got that one writer that they can go to when they’re in need of inspiration or comfort. That one writer that seems to say everything that needs to be said about whatever is ailing you when you pick up their book. That, for me, is Manly Wade Wellman. I think “The Third Cry to Legba” is the perfect occult detective story, and that “Nine Yards of Other Cloth” is as fine a tale of romance, ravenous horrors and redemption as you’ll find.

‘Pray for Hosea Palmer’. That chokes me up every damn time. If you know what I’m talking about, you’re probably tearing up a little too, because…yeah. If you don’t, you need to educate yourself, because you’re missing out.

Manly Wade Wellman taught me more about writing than any English teacher or creative-writing professor. He taught me that stories had to have a rhythm, like songs, even if that rhythm is weird and wonky and sounds like Tom Waits on his twelfth coffin nail of a twenty-smoke set. That cadence is better than dialect, because you can never reproduce dialect without it looking silly, but cadence will carry the sound right where you want it to go in the reader’s imagination. He taught me about Gardinels and Shonokins.

I wish I could have met him.

Anyway, today’s his birthday, so I thought I’d just mention it.

Happy birthday, Mr. Wellman.

May 15, 2021

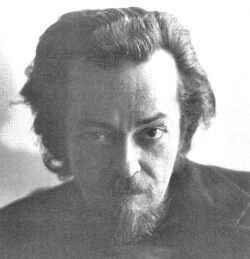

The Supernatural Sleuth

Yes, I can help you. But I can promise nothing!

– Anton Zarnak

Anton Zarnak is a man of mystery. With a jagged streak of silver running through his black hair from his temple to the base of his skull and his exotic features and peculiar mannerisms, Zarnak is almost as outré as the enemies he fights.

With a startling knowledge and a somewhat sinister history, Zarnak battled evil in three stories penned by his creator, Lin Carter-“Curse of the Black Pharaoh”, “Dead of Night”, and “Perchance to Dream”-as well as in a half dozen or so more contributed by the likes of Robert M. Price, CJ Henderson, Joseph S. Pulver Sr. And James Chambers. All of these stories, for those interested, are collected in Lin Carter’s Anton Zarnak: Supernatural Sleuth from Marietta Publishing.

Like the pulp characters Carter based him on, Zarnak is something of a Renaissance man. Educated at a number of prestigious universities, including the Heidelberg (where he studied theology with a certain Anton Phibes, according to “The Case of the Curiously Competent Conjurer” by James Ambuehl and Simon Bucher-Jones), the Sorbonne and Miskatonic University, he is an accredited physician, musician, theologian and metaphysicist.

He speaks eleven languages and has one of the finest and most complete collections of occult literature in existence. His home drifts like a soap bubble between Half-Moon Street in London, No. 13 China Alley in San Francisco and a cursed apartment building in New York; always decorated in oriental splendour, it is filled to bursting with esoteric paraphernalia, including a hideously decorated mask of Yama which always hangs in a place of honour above Zarnak’s desk.

And, as the saying goes, ‘so a man’s home, his mind’-Zarnak is the proverbial odd duck. By turns consoling and caustic, arrogant and affectionate, and almost inhumanly ruthless, Zarnak is no comforting Judge Pursuivant or soothing John Silence. He is singularly and irrepressibly Zarnak.

The Zarnak stories, like Robert E. Howard’s Conan, are perhaps best taken not as linear escalation (despite the wonderful work done in that regard by Matthew Baugh) but rather as a mythic cycle. Zarnak is bigger-than-life and a hero-with-feet-of-clay, moving between extremes of archetype throughout the stories.

In “Curse of the Black Pharaoh”, Zarnak is pulp-perfect; there’s no fear of him losing his battle with the devil-mummy of Khotep. In other stories, such as Carter’s second Zarnak story “Dead of Night” or “Keeper of Beasts” by James Chambers, Zarnak is very much on the back foot, scrambling for time he doesn’t have and a solution that won’t come in order to save those who’ve come to him for aid. Zarnak fails in both cases to accomplish what he set out to do, though his failure is mitigated by the perfidy of the victims themselves.

Of Zarnak’s origins, sources differ. Some hint that he was once a simple country doctor whose wife and newborn child were ripped from him by the fangs and claws of a werewolf. His hunt for the beast led him to become the world’s preeminent occultist. Other stories say that he stalked the snows of the high plateau of Leng as the lord and master of the hideous Tcho-Tcho people, and was the mouthpiece of the twin nightmares Zhar and Lloigor. Still others claim he is merely the next in a long line of supernatural defenders stationed at the strange house at No. 13 China Alley in San Francisco, trained in a distant monastery to confront the unimaginable horrors that lurk unseen along the borders between this world and the next.

Regardless of his origins, Zarnak stands as a fiercely intelligent and fearless sleuth and monster hunter. God, demon, beast or ghost, he pursues them all with exuberance and an almost diabolical mania. He is aided in these hunts by a grimly loyal man-servant, Ram Singh. Like Zarnak, Singh is something of an enigma. Some say that he owes Zarnak a debt of honour for rescuing him from a weretiger in his native India. Others say that Singh is the servant of whoever resides in No. 13 China Alley, and that his service to Zarnak is grudging at best. A Rajput or a Sikh depending on the story, Singh is the scion of a warrior caste with the skills to back it up. Swordsman, gunman, and occasional strangler and bone-breaker, Singh acts as Zarnak’s strong right hand, shielding his master from physical attack.

Besides Singh, Zarnak has a number of acquaintances, among them Anton Phibes, Dr. Stephen Strange and Jules de Grandin, who are all frequently mentioned in the stories, both by Carter and otherwise. Zarnak has fought side-by-side with Steve Harrison, Inspector Legrasse and Teddy London as well. These crossovers (acknowledged or otherwise) serve to add to the super-heroic nature of Zarnak. If HP Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos had a Superman analogue, it would be Anton Zarnak. He displays both great power and great responsibility, and his struggles often encompass great odds, whether global, dimensional or personal.

And when those odds finally prove too great, as Matthew Baugh so eloquently puts it, Zarnak “…leaves the world, not through death, but with the assumption of a new struggle.”

*Author’s Note: This essay originally appeared in 2011, at Black Gate Magazine.*

April 24, 2021

Dig the Dead

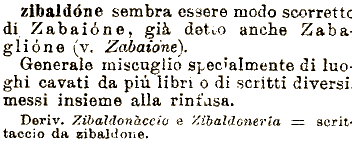

“The church of St. Mawgan, in Kerrier, was formerly at Carminowe, at the end of the parish. It was removed thence to its present site on account of the ghoulish propensities of the giants, who used to dig up the dead from their graves. The in-habitants tried in vain to destroy them by making deep pits, and covering them over with “sprouse” (light hay or grass) so that the unwary giants, walking over them as on firm ground, might fall into them and be killed. As this project failed, they were reluctantly compelled to remove the church to its present place, beyond the reach of their troublesome neighbours.”

– Rev. S. Rundle, Penzance Natural History Society, 1885-1886.

Just a neat little thing from my commonplace book. I ganked it from Cornish Feasts and Folklore (1890), by Margaret Ann Courtney, a book I found in a charity shop for 50p, along with the 1885 edition of The Ingoldsby Legends–also 50p. I wound up using it as the basis for my short story, “Unquiet in the Earth”, available in the anthology, Sockhops and Seances, from 18thWall Productions. Why not check it out?

If you’d like to read Cornish Feasts, you can check out and/or download a scanned copy thanks to the Internet Archive.

April 9, 2021

Untold Stories

“What are you complaining about, J? You’re getting paid, aren’t you?”

That was Derrick’s go-to whenever I started to moan about something – a bad review, a crap project, an editor I wanted to punch, that sort of thing. He knew just when to deliver that line, too. Just as I was building steam and my accent started to thicken, just when obscenities started to become punctuation…

“What are you complaining about, J? You’re getting paid, aren’t you?”

Boom. And down I went. Every time.

I don’t have many friends. Not good ones. I am not a friendly person. I am largely ambivalent to the affairs of others.

Derrick Ferguson was my friend. He died a few days ago. I found out today. I can’t imagine what his wife, Patricia, is going through. Though I don’t know her, I feel like I do, if only because Derrick was always talking about her. We talked to each other about our wives, our families, our aches and pains.

Mostly, we talked about stories.

We didn’t talk enough, though. Not lately. I had my excuses – work, my daughter, etcetera ad nauseum – but they all ring a bit hollow now. Survivor’s guilt.

I had another post planned today, but I knew that if I didn’t write something about him now, today, I probably wouldn’t. I knew the longer I waited, the less meaningful what I wrote would be. It would be anodyne and professional. The dutiful commemoration of a fellow professional.

But Derrick was my friend. We talked about stories. Stories we’d written, and wanted to write. The stories of others that we admired or hated, or both. We talked about our work, and what we were working on.

Derrick was always working, always coming up with stories he wanted to tell. Always trying to figure out the best way to get those stories out there, to the people who might want to see them. Who might need them.

“I don’t know, man – who’s this story for?” I asked, one time. Stupid question. I have – had – still have – a bad habit of thinking that ‘market’ and ‘audience’ are interchangeable. Derrick knew better.

He laughed – whatever else, I could always make him laugh – and said, “It’s for me, J. I just write what I want to read.”

He wrote what I wanted to read, too. Whatever it was, when it arrived in my mail box, on my computer, whatever, I put aside whatever I was reading at the time to dig in to it. Dillon, Sebastian Red, Diamondback Vogel – Derrick came up with some wild yarns. Some good stories.

Better than me on my best day.

Derrick knew how to write a story that would grab hold of you and not let go ’til you’d gotten to the end – and he’d leave you wanting more. Don’t believe me? Check one of his books out for yourself. There’s quite a few. Read them, then reread them.

Cherish them. Because there won’t be any more.

It’s selfish of me, but my head keeps spinning back to that singular thought. No more stories. No rematch between Diamondback Vogel and Nickelby Laloosh. No more Dillon, or Eli Creed. No more Xonira, no more…

No, that’s not true, is it?

The stories he wrote are there. And the stories he didn’t get to write are there too. An infinity of untold stories, in my head, and the heads of all the rest of us – those of us he taught and tended. Not just me but so many others.

Derrick meant so much to so many of us. Those of us he talked down off of the ledges, and out of making bad decisions. Those of us he convinced to keep going, to keep writing, to keep telling stories when we wanted to give up for whatever reason.

Those of us he told the secret of how to write a good story.

“I just write what I want to read.”

I forget that sometimes. Too often, of late.

I didn’t want to be reminded this way.

Do yourself a favour – do me a favour. Check out Derrick’s stories, if you haven’t already. Read his movie reviews, his interviews. Read them. Cherish them. Because he’s in every one of them. His humour, his soul. Derrick put himself into every story he told.

Just as he’s there in every story he didn’t get the chance to tell.

Rest in peace, my friend. The world was better for having you in it, and emptier by far with your passing.

I’ll miss you.

I’ll miss your stories.

April 2, 2021

Men From the Ministry

Today’s entry in the Royal Occultist Compendium delves into the bureaucratic wrangling of the Ministry of Esoteric Observation and Containment.

The Ministry of Esoteric Observation and Containment was formed in 1907, following the disappearance of Edwin Drood, the then Royal Occultist. Drood, a firm believer in the rational sciences and the observation, classification and regulation of the eldritch and aetheric, privately supported the formation of a governmental body to deal with what had, until then, been the sole province of the Queen’s Conjurer.

The Ministry, while small at first, wielded – and still wields – influence out of proportion with its size and oversight budget. As the world grows smaller and more complex, many in His Majesty’s government feel that final authority concerning occult matters should be held not by one man, but by an organisation of dedicated civil servants, who can be better prevailed upon to put the good of the nation first, and dedication to obsolete and eldritch and, frankly, heathen, matters, second.

As such, the Ministry is on record as believing that the responsibilities of the Royal Occultist would be better undertaken by the Ministry itself, all evidence to the contrary. To this end, the Ministry has made a number of attempts over the years to circumvent the office of the Royal Occultist – often to the detriment of those involved. Nonetheless, the Ministry shows no signs of relenting in its pursuit of these powers, or of those belonging to independent bodies such as the Westenra Fund or the London Tunnel Authority.

The Ministry is most often represented in its affairs by the enigmatic Mr. Morris – almost certainly a pseudonym – a bland individual of unassuming appearance and diffident manner. As the Ministry’s representative, Morris has made it his personal mission to take the lawless demimonde of London – and England – in hand. That includes the Royal Occultist. While Drood’s successor Carnacki often clashed with the Ministry in matters magical, his successor, Charles St. Cyprian, has worked with Morris and the Ministry on more than one occasion, including the Seeley Affair of 1921.

Despite this mostly amiable working relationship, however, St. Cyprian and Morris have found themselves at odds on occasion – something which has begun to occur with more frequency in recent years.

The idea of a governmental body tasked with investigating the occult isn’t a new one. It’s a fairly common trope of urban fantasy and modern occult detective fiction. Which, honestly, is why I decided early on to add it as a background element to the Royal Occultist – I love tropes and clichés, and a series like this should be full to bursting with them. Too, ‘the gentleman amateur replaced by a bureaucratic body’ is a trope of espionage fiction, which the series draws from as much as works by Hodgson and Benson, though somewhat more subtly.

The Ministry is often embodied in its appearances by a bureaucrat named Morris. Whether this is his real name or an assumed one is never revealed, but the implication is the latter. A fussy, egg-shaped man, Morris is a monster through and through – a sort of nastier George Smiley, only thirty years early and with fewer redeeming qualities. His successors – also named Morris – are, if anything, even worse, as seen in stories such “Unquiet in the Earth” and “Cheyne Walk, 1985”.

Morris, and by extension the Ministry, are good foils for St. Cyprian as well as good plot-motivators. If I ever run into trouble coming up with the impetus for a plot – it’s the Ministry’s fault. If I ever need a deus ex machina rescue – the Ministry can do it. If I ever need a villain that’s a cut above a werewolf or a cultist – rogue (or not so rogue) Ministry asset.

That said, I try not to use them too often. Like the Order of the Cosmic Ram, the Ministry is best used sparingly, and for bigger stories, with political or international implications. And like the Order, they’re always there, lurking in the background.

Observing.

If you’d like to check out some of the Royal Occultist stories for free, head over to my Curious Fictions page. For more general updates, be sure to check the Royal Occultist Facebook page.

March 21, 2021

Twice As Many Stars

Tomorrow when the farm boys find this

freak of nature, they will wrap his body

in newspaper and carry him to the museum.

– Laura Gilpin, “Two-Headed Calf”

I’ve got a handful of favourite poems. Most of them are weird or grotesque in some way, but beautiful nevertheless. In fact, their beauty is inextricable from their strangeness. They are monstrous, but affecting.

Laura Gilpen’s “Two-Headed Calf” is probably the gentlest of the lot. It’s a caress, rather than a slap.

Or maybe it’s a reminder of something – though what that might be is open to your interpretation.

But tonight he is alive and in the north

field with his mother. It is a perfect summer evening: the moon rising over the orchard

the wind in the grass. And as he stares into the sky, there are

twice as many stars in the sky.

– Laura Gilpin, “Two-Headed Calf”