Rob Tripp's Blog: Cancrime, page 4

February 14, 2017

Double cop killer denied release after denying he pulled trigger 43 years ago

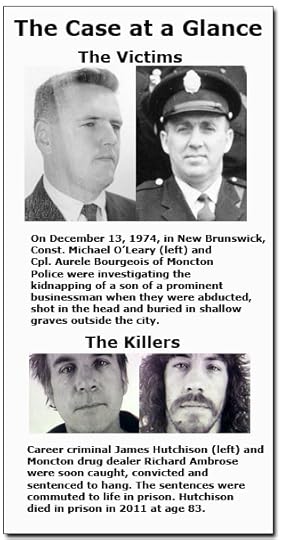

More than 40 years after Richard Ambrose (inset) was sentenced to hang for murdering two New Brunswick police officers, he is continuing to deny that he shot the victims. At a hearing in British Columbia this month, Ambrose, 68, told the parole board that he was only hired to “bury something” – he just didn’t know ‘something’ was the bodies of two policemen, Const. Michael O’Leary and Cpl. Aurele Bourgeois of the Moncton police department. At a hearing February 1 (read parole document, after the jump), the board refused Ambrose’s bid for full parole, noting that in the past year he has becoming increasing hostile with prison staff and he was charged twice with breaking prison rules. Ambrose, who has changed his name to Bergeron, was ordered to remain behind bars in B.C.

More than 40 years after Richard Ambrose (inset) was sentenced to hang for murdering two New Brunswick police officers, he is continuing to deny that he shot the victims. At a hearing in British Columbia this month, Ambrose, 68, told the parole board that he was only hired to “bury something” – he just didn’t know ‘something’ was the bodies of two policemen, Const. Michael O’Leary and Cpl. Aurele Bourgeois of the Moncton police department. At a hearing February 1 (read parole document, after the jump), the board refused Ambrose’s bid for full parole, noting that in the past year he has becoming increasing hostile with prison staff and he was charged twice with breaking prison rules. Ambrose, who has changed his name to Bergeron, was ordered to remain behind bars in B.C.

The parole board says, in it recent decision, that psychological testing completed recently showed that Ambrose is considered a moderate-high risk to reoffend. He’s considered a moderate risk for violence towards an intimate partner.

The parole board says, in it recent decision, that psychological testing completed recently showed that Ambrose is considered a moderate-high risk to reoffend. He’s considered a moderate risk for violence towards an intimate partner.

He has a long history of belligerence and threatening behaviour. The new parole record notes that “you have continued to make threats towards those you feel have wronged you.” It reveals that Ambrose made threats toward a lawyer who had worked for him. “The lawyer believed that you may be able to carry out such threats, so police and your [case management team] were both advised,” the written record of the February 1 hearing states.

Ambrose told the board that he wants to live on Vancouver Island, if he’s released but he provided no concrete release plan. He has no community support contacts in the area. Ever the pest, Ambrose warned the parole board that he intends to fight any decisions that keep him locked up and it’s his intention to “embarrass the Board and CSC” and pursue court action. Ambrose hasn’t been successful in the past. Last year, he was ordered to pay court costs to Corrections Canada after a failed court action.

Ambrose was released from prison on day parole in 1999 but, after a fall that caused a brain injury, he assaulted an intimate partner and made threats towards others. Ambrose has sometimes claimed that he doesn’t remember the 1974 murders that put him behind bars, because of his brain injury, although his latest claim that he didn’t pull the trigger seems to suggest he remembers precisely what transpired 43 years ago. The only person who could corroborate Ambrose’s claim about his lack of culpability is conveniently dead. James Hutchison, the mastermind of the 1974 kidnapping that led to the murders of O’Leary and Bourgeois, died behind bars in 2011 at age 83.

Hutchison and Ambrose kidnapped the 14-year-old son of a wealthy Moncton restaurateur, Cy Stein, in December 1974. Stein paid a $15,000 ransom to the kidnappers, who returned the boy unharmed. Police were hunting the kidnappers after the exchange. O’Leary and Bourgeois were part of the dragnet hunting the kidnappers and had been assigned to check out a suspicious car when they disappeared.

Hutchison and Ambrose subdued the two police officers and took them to a wooded area about 25 kilometres outside Moncton, where they were shot in the head and buried in shallow graves. (Read a detailed account of the crime).

Dale Swansburg, a retired RCMP officer who caught the killers, told me in 2009 that the pair should have been hanged. Their sentences were commuted to life in prison after capital punishment was abolished in 1976.

“When they committed the crime, there was capital punishment,” Swansburg said. “It should have been carried out.”

» Previous coverage of Ambrose and Hutchison and the 1974 murders

The written record of the February 1, 2017 parole hearing:

February 12, 2017

Infamous child killer Betesh admits crime was “bad” in penpal advert

Seven years ago, one of Canada’s most notorious imprisoned child killers, Saul Betesh (inset), began pursuing penpals on a U.S.-based website for lonely inmates. Betesh is now into his fourth decade behind bars and he’s still hunting friendship by letter. The reviled sex murderer has posted another online ad soliciting penpals, this time on a Canadian-based site. Betesh’s ad (screenshot after the jump) reveals that he’s no longer in Ontario – he was at medium-security Warkworth Institution near Campbellford, Ontario when he posted his 2011 ad – but he’s now at Pacific Institution, about 80 kilometres east of Vancouver. Six years ago, Betesh slyly concealed the horror of his crime. His ad described his offence only as “assault.” Now, he’s shown the temerity to confess he’s serving time for first-degree murder and acknowledges that “my crime was bad.”

Seven years ago, one of Canada’s most notorious imprisoned child killers, Saul Betesh (inset), began pursuing penpals on a U.S.-based website for lonely inmates. Betesh is now into his fourth decade behind bars and he’s still hunting friendship by letter. The reviled sex murderer has posted another online ad soliciting penpals, this time on a Canadian-based site. Betesh’s ad (screenshot after the jump) reveals that he’s no longer in Ontario – he was at medium-security Warkworth Institution near Campbellford, Ontario when he posted his 2011 ad – but he’s now at Pacific Institution, about 80 kilometres east of Vancouver. Six years ago, Betesh slyly concealed the horror of his crime. His ad described his offence only as “assault.” Now, he’s shown the temerity to confess he’s serving time for first-degree murder and acknowledges that “my crime was bad.”

Betesh says, in his new penpal ad (screenshot below, along with a screenshot of his 2010 ad) on Canadianinmatesconnect.com, that he’s a bit overweight, but that can be explained by 41 years of prison food. He’s a dungeons and dragons fan, a “practicing Druid Bard,” he plays chess, he works with stained glass and, he claims, sews quilts for charity. He also says that he reads, does work in the prison greenhouse and watches sci-fi television.

“In closing, I won’t lie to you,” writes Betesh, 66. “My crime was bad, but with treatment and a bit more time I feel I can once again become a productive member of society.”

As I said six years ago, when Cancrime revealed Betesh’s 2011 advertisement, he seems to have a knack for understating the gravity of his offence. “Bad” seems a miserably incomplete descriptor.

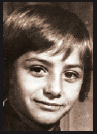

Betesh was convicted in 1978, along with Robert Kribs and Josef Woods, of the sexual torture and murder of 12-year-old Emanuel Jaques (inset right), a boy that Betesh plucked off a seedy section of downtown Yonge Street in Toronto, Ontario. Betesh offered Emanuel $25 to help carry camera equipment. Instead he took the boy to a flophouse above a body rub parlour where the boy was forced to engage in sex acts with the men. Betesh confessed the details to investigators and returned to the apartment with investigators to re-enact the murder. He explained that he and his accomplices were gay predators who regularly snatched boys off the street and forced them into sex acts. Betesh said he and Kribs took turns violating the boy for about two hours. After they had raped Emanuel, they fed him sleeping pills. They planned to release the drugged boy in a park, but Betesh said, in his confession that was read in court, that the pills didn’t work, so he tried to strangle the boy with a cord. After that failed, Betesh drowned Emanuel in a sink. The killers wrapped the child’s body in two plastic garbage bags and a plastic curtain and hid it behind a pile of lumber on the roof of the building. The conspirators were caught within days. A fourth man, Werner Gruener, was charged but was acquitted of first-degree murder at trial. Woods died behind bars in 2003. Kribs was denied parole in 2002.

Betesh was convicted in 1978, along with Robert Kribs and Josef Woods, of the sexual torture and murder of 12-year-old Emanuel Jaques (inset right), a boy that Betesh plucked off a seedy section of downtown Yonge Street in Toronto, Ontario. Betesh offered Emanuel $25 to help carry camera equipment. Instead he took the boy to a flophouse above a body rub parlour where the boy was forced to engage in sex acts with the men. Betesh confessed the details to investigators and returned to the apartment with investigators to re-enact the murder. He explained that he and his accomplices were gay predators who regularly snatched boys off the street and forced them into sex acts. Betesh said he and Kribs took turns violating the boy for about two hours. After they had raped Emanuel, they fed him sleeping pills. They planned to release the drugged boy in a park, but Betesh said, in his confession that was read in court, that the pills didn’t work, so he tried to strangle the boy with a cord. After that failed, Betesh drowned Emanuel in a sink. The killers wrapped the child’s body in two plastic garbage bags and a plastic curtain and hid it behind a pile of lumber on the roof of the building. The conspirators were caught within days. A fourth man, Werner Gruener, was charged but was acquitted of first-degree murder at trial. Woods died behind bars in 2003. Kribs was denied parole in 2002.

Betesh has never been reviewed for parole, even though he was eligible to seek full parole in 2002. He has waived his right for parole hearings, perhaps because he knows he will never be set free.

In prison, he has often been a lumbering pest, filing repeated complaints about his treatment. He engaged in numerous abortive hunger strikes to press demands. He always backed down, particularly in the face of derision by prison officials who noted that he was grossly overweight. In 2002, while he was incarcerated at Kingston Penitentiary, Betesh sent me a letter outlining his latest hunger strike manifesto, notably the ultimatum that he and a same-sex partner should be transferred together to another penitentiary. His demands were not met.

In 2011, he threatened to stop taking insulin to bring on kidney failure so that prison managers would face exorbitant costs to treat him. Betesh did not follow through on the threat.

The conviction in 1978 of Betesh, Kribs and Woods, set off a sweeping crackdown on Toronto’s Yonge Street sin strip of body rub parlours and porn houses.

Betesh’s recent ad on the Canadian Inmates Connect website and, below, his 2010 ad on an American penal site:

[image error]

February 8, 2017

Rapist’s return to Malaysia from Canada sparks calls for sex offender registry

There’s a growing clamour for creation of a sex offender registry in Malaysia, with the return to that country of serial rapist Selva Subbiah (inset), according to media reports from Malaysia. Subbiah, a remorseless and unrepentant predator who may be Canada’s most prolific rapist, was deported after completing a 24-year prison sentence for 75 crimes, including 26 sexual assaults against more than 30 victims. His sentence expired on January 29, 2017. Investigators believe he may have assaulted more than 1,000 women. He was flown to Malaysia on Monday, February 6, under guard.

There’s a growing clamour for creation of a sex offender registry in Malaysia, with the return to that country of serial rapist Selva Subbiah (inset), according to media reports from Malaysia. Subbiah, a remorseless and unrepentant predator who may be Canada’s most prolific rapist, was deported after completing a 24-year prison sentence for 75 crimes, including 26 sexual assaults against more than 30 victims. His sentence expired on January 29, 2017. Investigators believe he may have assaulted more than 1,000 women. He was flown to Malaysia on Monday, February 6, under guard.

A report in the Malaysian Times reveals that authorities are scrambling to figure out how to allay public fears while keeping tabs on a sexual predator who was assessed by Canadian authorities as a high risk to commit more violent sex crimes.

Other lawyers who agree said that the authorities should use the electronic monitoring device provided under POCA (Prevention of Crime Act) 1959 and POTA (Prevention of Terrorism Act) 2015. Lawyer Mohd Kamarul Arifin Mohd Wafa understood that POCA and POTA were to fight gangsterism and terrorism, but said they should be extended to include the effort to stop serial rape “especially if this is what society is asking for.”

The government itself seems to be leaning towards the creation of a sex offenders registry.

The Women, Family and Community Development said in a media statement on Sunday that there was an urgent need to speed up the creation of such a registry to monitor the movements of convicted sex criminals after their release.

Deputy Home Minister Nur Jazlan Mohamed had also called for such a registry for people to know if such an offender was residing in their neighbourhood.

Subbiah was detained in prison in Canada until he had served every day of his sentence because he was deemed too dangerous for early freedom. His parole records (available on Cancrime) noted that he continued to “demonstrate manipulative behaviour” behind bars, and, disturbingly, he insisted that many of the women who charged him “had lied in order to receive attention or monetary advantage.”

While it may look like Canada has dumped its problem on another country, Subbiah was long present illegally in Canada. He came to the country in 1980 on a three-month student visa that wasn’t renewed until 1983. The student visa was renewed multiple times but, in the meantime, Subbiah stole the identity of a Canadian, Richard Wild, and began masquerading as that man so that he could seek out sex assault victims while posing as a model talent scout or film producer. He Subbiah did not obtain permanent residency and was long ago declared a danger to society and subject to deportation. Subbiah eluded authorities by using fraudulent identity documents and multiple addresses. Below are photos of some of the documents found by police after Subbiah was arrested in Toronto in 1991.

[See image gallery at www.cancrime.com]

» One of the police officers who caught Subbiah explains how they ensnared him, in this podcast

» All coverage of Subbiah’s case

January 30, 2017

The inside story of how dogged cops caught Canada’s worst rapist

Canada’s worst rapist, a serial predator who may have assaulted more than 1,000 women, is free from prison and one of the investigators who caught him is certain he’ll strike again. But Selva Subbiah, 56, (inset) should not pose a threat in Canada. He’s being deported to his native Malaysia. Subbiah was caught more than 25 years ago because of the dogged work of police investigators who amassed a mountain of evidence that sent him to prison for nearly a quarter century. His penitentiary sentence in Canada expired January 29, 2017. Subbiah is an unrepentant manipulator and liar who insists that he presents “zero risk” to reoffend. Experts who have examined him conclude that he poses a high risk to commit more, violent sex crimes, despite treatment he’s undergone while behind bars. He was repeatedly denied parole because of the undiminished danger he poses. Subbiah was caught in 1991 by Brian Thomson and Peter Duggan, investigators in the Toronto police department. In the podcast (after the jump), Thomson recounts in detail how he and his partner ensnared Subbiah with an undercover operation and located a trove of evidence that was key to Subbiah’s conviction and lengthy sentence.

Canada’s worst rapist, a serial predator who may have assaulted more than 1,000 women, is free from prison and one of the investigators who caught him is certain he’ll strike again. But Selva Subbiah, 56, (inset) should not pose a threat in Canada. He’s being deported to his native Malaysia. Subbiah was caught more than 25 years ago because of the dogged work of police investigators who amassed a mountain of evidence that sent him to prison for nearly a quarter century. His penitentiary sentence in Canada expired January 29, 2017. Subbiah is an unrepentant manipulator and liar who insists that he presents “zero risk” to reoffend. Experts who have examined him conclude that he poses a high risk to commit more, violent sex crimes, despite treatment he’s undergone while behind bars. He was repeatedly denied parole because of the undiminished danger he poses. Subbiah was caught in 1991 by Brian Thomson and Peter Duggan, investigators in the Toronto police department. In the podcast (after the jump), Thomson recounts in detail how he and his partner ensnared Subbiah with an undercover operation and located a trove of evidence that was key to Subbiah’s conviction and lengthy sentence.

I’ve written often about Subbiah, while tracking his case for nearly 20 years. (Read all Cancrime coverage here, including parole records). After he was stabbed by fellow convicts at Kingston Penitentiary in 2009, Subbiah launched a federal court action that alleged that the parole board and Corrections Canada were negligent. In a patently absurd claim, Subbiah complained that the parole board violated his privacy by releasing the written record of a 2008 decision to me, which I then posted on Cancrime.com. Parole hearings are open to the public and the written records of decisions by the board also are publicly available. Subbiah claims other prisoners discovered he was a sex offender from the posting on Cancrime – sex offenders are reviled in prison. Subbiah’s claim was thrown out, after witnesses explained that his background was well known at the prison.

Subbiah served a 24-year sentence for 75 crimes, including 26 counts of sexual assault, 27 charges of administering a noxious thing and other charges of procure/attempt to procure as prostitute and extortion. He was convicted of crimes against more than 30 victims including four who were in a relationship with him. Most of his victims were in their twenties but at least four were under the age of 18 and one was 14. Most of his victims were incapacitated after they consumed a drink laced with Halcion, a powerful sedative. Subbiah undressed, raped and molested the drugged victims and took photos and videos. Most victims did not know what had happened to them. In many cases, Subbiah posed as a movie producer or recruiter for models to arrange meetings with women.

In the podcast (embedded above), retired police investigator Brian Thomson explains that he’s certain there were at least 500 victims and perhaps more than 1,000, based on the records that Subbiah kept, including photos and videos that police found when they arrested him.

Subbiah will be “closely monitored” in Malaysia, according to a report in a Malaysian newspaper.

Inspector-General of Police Tan Sri Khalid Abu Bakar, based in Kuala Lumpur, told the Sun Daily that Subbiah will be permitted to live as a normal citizen as he has served his prison sentence.

“We have no rights to [prevent] his entry to the country,” the officer said, according to the report. “He has finished his jail term in Canada and will be coming here.”

Subbiah resisted treatment while behind bars and schemed to contact new victims from penitentiary. Using a female accomplice on the street, he sought phone sex and photos from women.

Says Thomson: “He damaged and hurt so many lives.”

Chronology of a Predator

•1980: arrived in Canada on a student visa

•1981: convicted of possession of stolen property, granted conditional discharge

•1988: convicted of public mischief, fined $300

• late 80s: stole information and assumed the identity of Richard Wild

•1991: arrested by Toronto Police in sting employing undercover female officer, charged with two counts of sexual assault, administering noxious substance; more victims came forward after his arrest was publicized

•1992: pleaded guilty to 14 counts of sexual assault and six counts of administering a noxious substance, jailed 16 years

• 1997: pleaded guilty to another 55 charges relating to more than 20 victims

• 2008: parole board ordered him kept in prison until he served every day of his 24-year sentence because he poses a high risk to commit new, violent sex crimes

• Jan. 29, 2017: sentence expires, will be deported to Malaysia; in 2008, Subbiah told the parole board he had a “structured release plan” for his freedom in Malaysia and had “strong family support”

Podcast music: Music For Podcasts 2 (Lee Rosevere) / CC BY-SA 4.0

November 2, 2016

Shafia honour killers lose appeal at Ontario’s top court

Nearly 10 years after Afghan native Mohammad Shafia brought his 10-member family to Canada, Ontario’s top court ruled that the controlling and abusive father got a fair trial when he was convicted, along with his second wife and eldest son, of murdering four family members. Shafia, his wife Tooba and son Hamed were not victims of prejudice and are not entitled to new trials, the Court of Appeal for Ontario says, in a judgment released today (Nov. 2, 2016). The three were each convicted in January 2012 of four counts of first-degree murder. Sisters Zainab, 19, Sahar, 17, Geeti 13 and Rona Amir, 50, who was Shafia’s first wife in the polygamous family, were found dead June 30, 2009, inside a sunken car resting at the bottom of a shallow canal in Kingston, in eastern Ontario.

Nearly 10 years after Afghan native Mohammad Shafia brought his 10-member family to Canada, Ontario’s top court ruled that the controlling and abusive father got a fair trial when he was convicted, along with his second wife and eldest son, of murdering four family members. Shafia, his wife Tooba and son Hamed were not victims of prejudice and are not entitled to new trials, the Court of Appeal for Ontario says, in a judgment released today (Nov. 2, 2016). The three were each convicted in January 2012 of four counts of first-degree murder. Sisters Zainab, 19, Sahar, 17, Geeti 13 and Rona Amir, 50, who was Shafia’s first wife in the polygamous family, were found dead June 30, 2009, inside a sunken car resting at the bottom of a shallow canal in Kingston, in eastern Ontario.

The victims (from left) Geeti, Sahar, Zainab, Rona

Jurors during the murder trial heard that Mohammad Shafia orchestrated the killings, believing it would restore his family honour. He felt it was tarnished because three of his daughters violated strict cultural rules around modesty and obedience and Rona supported them. Jurors heard that Hamed researched locations and means to commit the murders.

The trio appealed the convictions, arguing that their trial was unfair because of “overwhelmingly prejudicial evidence” and “cultural stereotyping.”

They attacked the evidence of University of Toronto professor Shahzrad Mojab, who was permitted to testify at the trial about the origins of honour killings. She wasn’t permitted to offer an opinion about whether the deaths of the four Shafia family members were honour killings.

“Dr. Mojab’s evidence was overwhelmingly prejudicial and should not have been admitted,” the killers claimed, in a document filed with the court. “Her evidence invited the jury to improperly find that the Appellants had a disposition to commit family homicide as a result of their cultural background and to reject their claim that they held a different set of cultural beliefs.”

The manner in which Mojab’s evidence was presented “created enormous prejudice” and invited jurors to decide contested factual issues by relying on “cultural stereotyping,” according to the document.

“By reinforcing pre-existing stereotypes of violent and primitive Muslims, it created the risk that the jury’s verdict would be tainted by cultural prejudice,” the document states. It was prepared jointly by three lawyers representing the trio and argues that while some of Mojab’s evidence may have been admissible, the judge failed to “limit its scope and its potential for prejudice.”

The appeal court rejected the arguments.

“The evidence of Dr. Mojab was properly admitted as expert opinion evidence,” the court states, in its decision. “Its introduction was closely monitored to ensure what the jury heard did not exceed what the trial judge permitted after two pre-trial motions to exclude it. Neither the trial Crown nor the trial judge invited or instructed the jury to use this evidence in any impermissible way in deciding whether the Crown had proven its case beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Shafia also argued that the court should reconsider the conviction of Hamed because of new documents that he claimed he had obtained that purportedly show Hamed was not 18 at the time of the murders.

“The interests of justice do not warrant the reception of the proposed fresh evidence documents,” the court ruled.

In refusing to consider the material, the court noted that “tellingly, the only accurate source of information about Hamed’s date of birth – Tooba – has not filed an affidavit on the motion. Her police statement and trial evidence supports the conclusion that Hamed was 18 when the deceased were killed.”

***

Everything you need to know about the appeal court judgment, in less than four minutes:

» All Cancrime coverage of the case

» Buy my book on the case, Without Honour

July 15, 2016

Rapist/killer given most permissive parole

Killer James Giff convinced the parole board he’s not a threat to reoffend if given the least restrictive form of freedom from prison but, in an unusual step, the board barred the murderer from accessing social media such as Facebook and Instagram. Giff, who raped and stabbed a 16-year-old girl, then left her to die in a snowbank, was granted full parole, a form of early release from penitentiary that permits him to live on his own, without direct daily supervision. It’s a big step for a criminal once classified as a sadist, and who spent most of the past 30 years behind bars. The parole board decided, after a hearing July 7, that Giff won’t present an “undue risk to society” but it imposed several special conditions on his full parole (read them all in the parole document, after the jump). Giff has been living and working in Montreal.

Killer James Giff convinced the parole board he’s not a threat to reoffend if given the least restrictive form of freedom from prison but, in an unusual step, the board barred the murderer from accessing social media such as Facebook and Instagram. Giff, who raped and stabbed a 16-year-old girl, then left her to die in a snowbank, was granted full parole, a form of early release from penitentiary that permits him to live on his own, without direct daily supervision. It’s a big step for a criminal once classified as a sadist, and who spent most of the past 30 years behind bars. The parole board decided, after a hearing July 7, that Giff won’t present an “undue risk to society” but it imposed several special conditions on his full parole (read them all in the parole document, after the jump). Giff has been living and working in Montreal.

Giff was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years, after he raped and stabbed to death Heather Fraser, 16, in Smiths Falls, a small town in eastern Ontario, in 1985. Giff told me, in the only interview he’s ever granted, that Heather was a random target, a victim of his uncontrollable rage to kill and his furious hatred of women. He had intended to kill his girlfriend at the time, Annette Rogers. Giff committed the murder when he was 17 and he insists that he has changed.

A recent edition of the Cancrime podcast features an interview with Rogers. The accompanying story features a detailed account of the murder of Heather Fraser and the investigation that led to Giff’s arrrest and conviction. The story includes crime scene photos and other key documents available exclusively on Cancrime.

All of the decisions made by the parole board in Giff’s case are available in the PAROLE RECORDS library.

Here’s the written record of the decision made July 7, 2016, granting Giff full parole:

May 19, 2016

Psychopathic predator free again despite “harassing a vulnerable female”

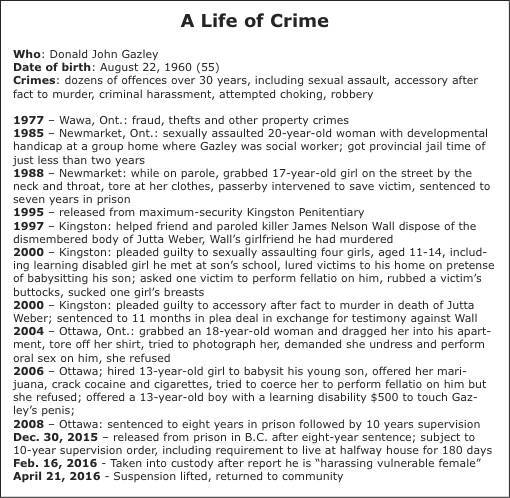

A psychopathic sex offender has been set free again in British Columbia, after being briefly detained, despite the revelation that he was “harassing a vulnerable female” near the halfway house where he’s under supervision and other troubling discoveries. Authorities expressed “significant concern” after learning that Donald Gazley (inset) secretly struck up a pen-pal relationship with a female sex offender in a U.S. prison – a woman who helped a man abuse her daughters. Gazley has a three-decades long criminal record that includes sex crimes against children and vulnerable adults and a conviction for involvement in a murder. He appears to be a rare and particularly dangerous offender – a sexual psychopath who preys on children and adults, male and female. Most offenders like him resist treatment and never stop committing crimes.

A psychopathic sex offender has been set free again in British Columbia, after being briefly detained, despite the revelation that he was “harassing a vulnerable female” near the halfway house where he’s under supervision and other troubling discoveries. Authorities expressed “significant concern” after learning that Donald Gazley (inset) secretly struck up a pen-pal relationship with a female sex offender in a U.S. prison – a woman who helped a man abuse her daughters. Gazley has a three-decades long criminal record that includes sex crimes against children and vulnerable adults and a conviction for involvement in a murder. He appears to be a rare and particularly dangerous offender – a sexual psychopath who preys on children and adults, male and female. Most offenders like him resist treatment and never stop committing crimes.

Gazley was taken into federal custody on February 16, 2016, seven weeks after he was released from a penitentiary in British Columbia. Sources tell me that Gazley had been released to a community residential facility, a site similar to a halfway house, in North Vancouver. His eight-year sentence for sex crimes committed in Ottawa, Ontario had expired but he was subject to a 10-year supervision order that included seven special conditions. The supervision order is a seldom-used legal leash reserved for dangerous, persistent criminals, particularly sex offenders who resist treatment.

Gazley was taken into federal custody on February 16, 2016, seven weeks after he was released from a penitentiary in British Columbia. Sources tell me that Gazley had been released to a community residential facility, a site similar to a halfway house, in North Vancouver. His eight-year sentence for sex crimes committed in Ottawa, Ontario had expired but he was subject to a 10-year supervision order that included seven special conditions. The supervision order is a seldom-used legal leash reserved for dangerous, persistent criminals, particularly sex offenders who resist treatment.

In late April, the parole board reviewed the troubling discoveries about Gazley’s behaviour during his seven weeks of freedom and decided to turn him loose again. His case management team recommended to the board that the suspension of his release be cancelled, even though the board was given “no further details about who you apparently harassed or how you harassed her,” according to the written record of the April 21, 2016 parole decision (read entire document below).

Gazley denied the harassment allegation.

“At your post-suspension interview when you were told by [Correctional Service Canada] that you were harassing a vulnerable female to the point in which she felt concerned for her safety, you claimed you had no recollection of doing so,” the parole document states.

Gazley is an admitted, chronic liar and manipulator. He confessed, during his testimony during a murder trial in Ontario in 2002, to lying “almost … all the time” when talking to police about the murder, before striking a deal for a lenient sentence in exchange for his testimony against the killer. Gazley was diagnosed in 1991, during a prison evaluation by a psychiatrist, as a “classic psychopath with all the typical features of superficial charm and good intelligence, manipulativeness, lack of true remorse, untruthfulness and insincerity.” (Learn more about Gazley’s past and psychopaths in this story and podcast).

Gazley has continued to reoffend despite going through many treatment programs during his multiple terms in prison and jail. His criminal record begins in 1977. Treatments given to sexual psychopaths “have shown little or no reduction in recidivism rates,” according to research by forensic psychologist Stephen Porter, an expert on psychopaths. His research shows that Gazley fits into a category of criminals who “can be expected to offend early, persistently, and often violently across the lifespan.” (Porter appears in Episode 4 of the Cancrime podcast)

Gazley was turned loose again by the parole board despite the alarming discoveries about his behaviour. New conditions were imposed that require him to continue living at a community based facility for another year, to immediately report any attempts to initiate sexual and non sexual friendships with females, not to associate with anyone involved in criminal activity or substance abuse and not to be “in, near or around places where children under the age of 18 are likely to congregate such as elementary and secondary schools, parks, swimming pools and recreational centres unless accompanied by an adult previously approved in writing by your parole supervisor.”

In addition to his sex-offending pen pal and his harassment of a female, authorities also found in his room at the halfway house a pamphlet for a youth business program. Many of Gazley’s victims have been boys and girls aged 11 to 14. A search of his room also turned up a list of names of federal offenders, including their confidential FPS (fingerprint sheet) numbers. Gazley claimed he was given the list when he was a peer counsellor in prison.

The new conditions were imposed on Gazley’s renewed freedom because he appears to be testing the boundaries of his supervision order and challenging authorities charged with watching him.

Despite his history of abusing vulnerable adults and children, and despite specific direction that he cannot “take on any role of trust, coaching or volunteering with community members,” he asked, after his release from prison in December, if he could volunteer as an English teacher for refugees. He was refused permission. He also has asked if he can work at a university campus in a position related to prison health care. On another occasion, Gazley asked staff at the halfway house to help him apply for a pass to attend a community centre so he could exercise and go swimming. Gazley also argued with his case management team, according to the recent parole record, when he was told he could not socialize with other sex offenders in the community. His case management team “notes the concern is significant given that associates have been a factor in your offending.”

Gazley has proven problematic for staff supervising him. He has complained that they have “spoken down” to him. He claims that he has been “isolated in the community” and he has expressed frustration at the way his case has been managed. The parole document reveals that, before Gazley was released from penitentiary in December, another inmate accused Gazley of sexually assaulting him.

The parole board decided to set Gazley free again because it concluded that he does not presently pose “a substantial risk of reoffending.”

“You are clearly a challenge for your [case management team] to manage,” the board stated. “You are argumentative and oppositional but to date you have apparently not breached any of your special conditions or disregarded the clear instructions of your CMT to the point that you have become unmanageable or that you were preparing to do so.”

***

The written record of the decision by the Parole Board of Canada April 21, 2016, lifting the suspension of Gazley’s release:

***

» Listen to Gazley in manipulation mode in Episode 4 of the Cancrime podcast

» Gazley’s parole records from 2013-16

May 13, 2016

Infamous Kingston Pen throwing open gates to public, again

When the Conservative government shuttered 178-year-old Kingston Penitentiary, Canada’s oldest prison, in the fall of 2013, it was briefly opened for two rounds of public tours. Tickets, at $20 each with proceeds to charity, were snapped up quickly and the website selling them crashed under demand. Many people were left disappointed. Unfulfilled curiosity for what lies beyond the 10-metre high, truck-thick stone walls will be satisfied this summer, with the announcement that public tours will resume in late June 2016 and run until the end of October. The tours are possible because the 20-acre complex is mostly empty and disused. While tours may offer a fascinating view of prison conditions, did you know you could have owned a piece of the pen, for a pittance?

When the Conservative government shuttered 178-year-old Kingston Penitentiary, Canada’s oldest prison, in the fall of 2013, it was briefly opened for two rounds of public tours. Tickets, at $20 each with proceeds to charity, were snapped up quickly and the website selling them crashed under demand. Many people were left disappointed. Unfulfilled curiosity for what lies beyond the 10-metre high, truck-thick stone walls will be satisfied this summer, with the announcement that public tours will resume in late June 2016 and run until the end of October. The tours are possible because the 20-acre complex is mostly empty and disused. While tours may offer a fascinating view of prison conditions, did you know you could have owned a piece of the pen, for a pittance?

Full details of the 2016 KP tour program aren’t yet available. A news release (full document below) issued today (May 13, 2016) notes that this is a co-operative project between the City of Kingston, Corrections Canada and the St. Lawrence Parks Commission, a provincial agency.

“In response to tremendous interest in KP, all three levels of government are working together to temporarily open the site to the public for the 2016 tourism season as part of the City’s larger visioning exercise,” the release states. It’s notable that authorities say the prison is being opened to the public “temporarily,” certainly an attempt to quell anticipation that this is a step toward turning the disused pen into a permanent tourist attraction – an idea that has been promoted since the closing in 2013.

Tickets for the tours will be sold exclusively through a parks commission-operated website and will go on sale in mid June. Tours will be offered six days a week from mid-June to August 31 and on select days September to October.

It appears that the chance to own a piece of KP has passed. When the Harper government announced it would close Kingston Penitentiary, along with the accompanying regional treatment centre and a prison in Quebec, it claimed it would save $120 million annually. Canada’s correctional investigator told me he never understood where those savings would come from. It’s possible that Corrections Canada thought it could earn a few bucks peddling the accoutrements of punishment, particularly given the knowledge that these bits and pieces were once the furnishings of the country’s most vile criminals – Paul Bernardo, Russell Williams, Saul Betesh and many others. It seems there were few buyers, and certainly, none willing to pay big bucks for the guts of Kingston Pen that were put on the block.

Corrections Canada tried to sell, through the government’s surplus goods website, hundreds of plastic bunk/desk units that were installed in many of Kingston Pen’s inmate cells. Screen captures that I’ve saved from the past few years (see them below) show that in the summer of 2015, CSC was still flogging them. Some sold for as little at $1.33 each (note the lot of 57 that sold for $76). Some individual pieces sold for $1.99. It appears that many of them didn’t sell and, as of May 2016, KP furnishings are no longer for sale on the surplus website. It’s unclear what those units would have cost Corrections when they were first installed at KP, but you can bet that it was far more than $1.33 each.

So what will you see if you take a KP public tour? This website, operated by a pair of urban explorers who call themselves Jerm & Ninja, offers terrific photos that were taken during one of the public tours in 2013 and also, clandestine photos taken during a short, unauthorized tour at the south perimeter of the prison.

[See image gallery at www.cancrime.com]

May 6, 2016

Witness to murder: “I will always blame myself”

Is a witness to evil, who does not intervene, culpable or guilty only of cowardice? Annette Rogers has been to this precipice. Her scarred conscience reflects her failure. She did not do the difficult thing, the right thing. If Rogers had, 16-year-old Heather Fraser (inset) might have survived her encounter with a killer. Fraser was raped and stabbed by James Harold Giff on a cold Monday evening, January 28, 1985, in Smiths Falls, a small town in eastern Ontario on the historic Rideau waterway. Rogers was Giff’s girlfriend at the time. For nearly 25 years, she kept a terrible secret about the murder, until she spoke to me in 2009 (the podcast, after the jump, features her interview). Rogers revealed that she was taken by Giff on the night of the murder – in an act that would forever bind her to that night’s horror – to the snowy park where he had left his victim after raping her and stabbing her twice. Heather wasn’t dead. Bleeding profusely, she was crawling on her hands and knees through nearly two foot deep snow toward a nearby street. Rogers says she heard – but could not see in the dark – Heather’s faint cries for help. Rogers did not do the right thing. She did not run to Heather’s aid, or call police or for an ambulance. She agreed with Giff’s demand for silence, and assistance. She became, for a time, an accomplice. Heather was found hours after she was attacked and was rushed to hospital where she later died. Rogers says her inaction stemmed from fear that Giff would kill her. He had threatened her many times in their abusive relationship, she says. After Giff was jailed for Heather’s murder, Giff warned Rogers that he would hunt her down after release and kill her. This lingering threat has driven Rogers, in an act of self flagellation, to attend every one of Giff’s parole hearings, to listen over and over again to the sordid details of his crimes, and to plead with authorities not to free him. Giff was granted day parole to a halfway house in Montreal in January 2015, but nine months later, his release was suspended, then reinstated. Corrections Canada, which was responsible for supervising Giff’s freedom, refused, at the time, to disclose why Giff’s parole was suspended. Recently, the Parole Board of Canada released documents (read them after the jump) that reveal Giff had a “change of attitude” that sparked concern.

Is a witness to evil, who does not intervene, culpable or guilty only of cowardice? Annette Rogers has been to this precipice. Her scarred conscience reflects her failure. She did not do the difficult thing, the right thing. If Rogers had, 16-year-old Heather Fraser (inset) might have survived her encounter with a killer. Fraser was raped and stabbed by James Harold Giff on a cold Monday evening, January 28, 1985, in Smiths Falls, a small town in eastern Ontario on the historic Rideau waterway. Rogers was Giff’s girlfriend at the time. For nearly 25 years, she kept a terrible secret about the murder, until she spoke to me in 2009 (the podcast, after the jump, features her interview). Rogers revealed that she was taken by Giff on the night of the murder – in an act that would forever bind her to that night’s horror – to the snowy park where he had left his victim after raping her and stabbing her twice. Heather wasn’t dead. Bleeding profusely, she was crawling on her hands and knees through nearly two foot deep snow toward a nearby street. Rogers says she heard – but could not see in the dark – Heather’s faint cries for help. Rogers did not do the right thing. She did not run to Heather’s aid, or call police or for an ambulance. She agreed with Giff’s demand for silence, and assistance. She became, for a time, an accomplice. Heather was found hours after she was attacked and was rushed to hospital where she later died. Rogers says her inaction stemmed from fear that Giff would kill her. He had threatened her many times in their abusive relationship, she says. After Giff was jailed for Heather’s murder, Giff warned Rogers that he would hunt her down after release and kill her. This lingering threat has driven Rogers, in an act of self flagellation, to attend every one of Giff’s parole hearings, to listen over and over again to the sordid details of his crimes, and to plead with authorities not to free him. Giff was granted day parole to a halfway house in Montreal in January 2015, but nine months later, his release was suspended, then reinstated. Corrections Canada, which was responsible for supervising Giff’s freedom, refused, at the time, to disclose why Giff’s parole was suspended. Recently, the Parole Board of Canada released documents (read them after the jump) that reveal Giff had a “change of attitude” that sparked concern.

NOTE: This is an updated version of a story first published in 2009. It includes new information, new documents and a new podcast that includes portions of my recorded interview with Annette Rogers not previously released.

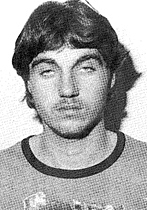

Rapist/murderer James Giff, at age 17

In its latest decision, dated April 22, 2016, the parole board ruled that Giff can continue to live in Montreal on day parole but he won’t be granted full parole, which brings far greater freedom, until a full hearing is held. The April 22 decision was made on paper. Giff’s case management team had recommended he be granted full parole. But the parole board noted that Giff “had been incarcerated for almost the entirety of your adult life, and that you have only been in the community on Day Parole for a relatively brief period of time.”

“Full parole is a major step in your reintegration into society, and brings with it stresses and risks with which you will be confronted,” the parole board decision states. “In order for the Board to properly evaluate the risk that Full Parole may present and to assess the extent to which it would be appropriate for you to take this further step, it will be necessary for the Board to meet with you in a hearing. At that time, you will have the opportunity to exchange with the Board with respect to your request to be granted Full Parole.”

Another parole document, the written record of a decision January 27, 2016, reveals that Giff was behaving “out of anger and a sense of revenge” when his parole was suspended late last year. The behaviour was linked to his failure to call a parole supervisor to report his arrival at a planned destination. Giff lost privileges at the community facility where he was living on day parole but he didn’t like the sanction. He became, according to the document, “legalistic and demanding” and, at one point, he “alluded to bringing down the institution.”

In the end, his parole was reinstated. Giff was permitted to continue to live at a community correctional centre. He is doing volunteer work and began working in January at a paid job as an assistant cook (he took cooking instruction in prison), though the employer is not revealed in the documents. He’s also taking karate lessons, which, the parole board notes, “like your faith, help you to maintain a balanced lifestyle.”

Giff continues to live under conditions that forbid him from using drugs or alcohol. He must report all intimate relationships and friendships with females and he must avoid contact with people in the drug subculture.

***

Here is my account of the murder of Heather Fraser, first published in The Kingston Whig-Standard newspaper November 2009:

Heather Margaret Fraser was the daughter every parent hoped to raise.

In Grade 6, she was named outstanding student in her school. In Grade 8, she was president of her student council. She was awarded one of the Girl Guides’ highest honours.

As a teen, she began to teach Sunday School at her family’s Presbyterian Church.

At Smiths Falls District Collegiate, she joined the student council. She won spots on school basketball, volleyball and badminton teams. She was a member of the school band.

With excellent grades, she was enrolled in the school’s gifted program. Outside of school, she played ringette and softball. She won medals in highland dancing competitions.

She worked part time at the canteen at the community centre and the arena.

The tall, brown-eyed Grade 11 student with short-cropped hair and a big smile had no enemies.

Though she lived in a small, historic eastern Ontario town known for its railway roots and a chocolate factory, her father Ian, a construction supervisor with Parks Canada, had always cautioned her about walking in some places, after dark.

Smiths Falls had an underbelly, though invisible to most. In a town of roughly 9,000 people, the regular troublemakers were well known to police, but mostly for petty crimes – break-ins, vandalism and fights fuelled by booze and drugs.

There had never been a sex murder in the town, until Jan. 28, a cold Monday in 1985 that fell one month after Heather’s 16th birthday.

Heather’s day began early.

Her mother Carolyn drove her to school shortly after 7 a.m. for volleyball practice.

After school, she attended a student council meeting.

It ended around 4:45 p.m. Friends saw her leave the school alone, bundled in her multi-coloured parka and blue sweatpants, around 5 p.m. Her books were stowed in her green canvas backpack.

Though she often called family for a ride, Heather decided to brave the 15-minute walk south from school to her home, despite the falling temperature and the fading light.

A cold southwest wind made it feel like –12 C. At eight minutes after 5, the sun set.

It was not fully dark when Heather reached Abbott Street. She followed the sidewalk that abutted the sprawling Parks Canada property where the Rideau waterway bisected the town.

The grassy expanse around the canal that lured children with fishing poles and picnickers in summer was now desolate, blanketed by 20 inches of snow. The day before, a few new inches had fallen.

Heather crossed the first of two bridges that spanned the waterway.

She was just three blocks from home when she met another solitary figure on the sidewalk.

James Harold Giff, a slight 17-year-old with bushy, shoulder-length brown hair, was wearing his signature Tuf Mac workboots. As he walked, the soles imprinted distinct wavy lines in the snow.

Heather did not know Giff.

Although they lived just a few doors apart, he existed in another world.

She might have run at first sight of him, if she had recognized the rage fermenting inside this troubled highschool dropout who viewed women as evil.

Giff had lasted just four months at Smiths Falls District Collegiate before continued brushes with the law landed him in a training school in the spring of 1983, at the age of 15.

He had been a drinking, thieving truant since the age of 11.

In 1984, he spent six months in a reformatory for his role in armed robberies at two Smiths Falls convenience stores.

Since his release, Giff had been living at his uncle’s house, at 58 Alfred St. Heather Fraser lived at the corner of Alfred and Abbott streets.

For parts of the past 24 hours, Giff had been guzzling cheap wine, swallowing Valium pills, and hunting the girlfriend with whom he lived, 17-year-old Annette Rogers.

He had threatened to choke, stab, or shoot the confused runaway who was his regular punching bag, the girl he often condemned as a lazy, stupid slut.

She was his slut, at least.

Like a terrified mouse, Rogers had scurried to a hiding place, waiting for the now-familiar fury to subside.

Something had clicked in her battered brain. She had the temerity to defy her abuser-lover and threaten to end their relationship.

At midday, Rogers spoke to Giff on the phone. He spewed more threats, warning her to come to their home and retrieve her belongings.

She refused to come out of hiding.

Her defiance stoked his rage.

Giff met Heather on the swing bridge that crossed the canal.

It was about 5:15 p.m.

She appeared, at least to him, like the stuck-up snobs who looked down their noses at him.

“Do you have a light?” Giff asked.

Heather said she didn’t smoke.

Giff pulled out the buck knife he always carried, the one he intended to use on Rogers.

The violent fantasies of harming women that had often possessed him were swirling in his brain.

“Follow me,” he told the terrified girl.

He ordered Heather to walk into the park, through the unbroken snow, away from the road and into the creeping darkness.

He marched her toward the rusting railway lift bridge at the western edge of the property.

•

Annette Rogers, in 1994

A sheaf of documents is sprawled across the thick pine table in Annette Rogers’ small kitchen, in a tiny eastern Ontario community where she lives with her husband and three children.

There are parole board reports, dozens of pages of victim impact statements – statements over which she laboured for hours, sometimes days – and newspaper clippings. The papers are a tangible reminder of a tortured life.

“People need to know the truth,” says Rogers, who seems too worn to be just 42.

Long, brown hair is pulled back from her face. She is calm. Words don’t always come easily or eloquently, but her message is clear.

“I think we better get the story out there, even if it’s going to cost me having to answer to a lot of things,” she says. “It needs to be done.

The truth is painful and she knows that she will be judged, not just for what she did, which has been obvious to most people, but for what she did not do, which has been secret, until now.

She was there, that cold night in the park nearly 25 years ago.

“I died that night,” she says, recalling Jan. 28, 1985.

So much life has since slipped away in a blur of drug abuse, self-induced torment and despair. After 16 years of therapy, frequent mental collapses and a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress syndrome, there is some clarity, and a fierce determination to keep a killer locked up and to purge her demons.

“He took me to the spot and I was one of the last people to hear her alive,” Rogers says.

When Giff found Rogers that day, she expected a beating or more threats, but instead, Giff asked her to go somewhere with him.

He told her he had done something terrible.

“He says, ‘I killed somebody,’ ” Rogers recalls. She did not believe him.

“I went along with him and the walk was pretty quiet because, you know, he wasn’t talking very much and I was still very uneasy.”

It was after 6 p.m., fully dark, when Giff led Rogers to the property along Abbott Street.

“When we got there, I didn’t hear nothing, did not hear nothing whatsoever so I walked up the bank,” Rogers recalls. “I walked up to where the bank is, the snowbank, and I stood there and I said like, ‘What are you talking about? I don’t hear nothing,’ and all of a sudden, you could hear her, very faint, yelling, trying to yell but she couldn’t even do that.”

Rogers did not go to toward the muffled sound of a young woman, crying out in agony.

She did not call police.

She did not go for medical help.

She went home with Jamie Giff.

Years of therapy have trained her to accept that she was a battered woman-child whose mind was traumatized, fractured, by what she saw and heard that night.

“I used to think that was a piss poor excuse for not doing the right thing, for not going and helping her, for not going to the police right there,” she says, her voice getting louder. “I could have done it.”

Now, she is pounding the table, her hand thumping the pine.

“I could have done it, you know,” she says, pausing to exhale in frustration.

She has been told, often, that she is not to blame.

“Ahhhh,” she says out of exasperation. “Does any of this make sense?”

•

Ken Graham, the police officer who pried a confession from Giff

Ken Graham has been retired 20 years from the Smiths Falls police department, but he has not forgotten Jan. 28.

“I vividly remember,” he says. “I was actually at the curling club, off duty and I was curling and I was hardly dressed for the winter.”

At 8:45 p.m., Graham received a phone call from his inspector.

Then a 10-year veteran of the department, Graham was ordered to come to the office immediately. A young girl had been assaulted in the Abbott Street park.

“I didn’t even have a gun with me, I didn’t even have my notebook, nothing,” says Graham, who became the department’s lead investigator on the case.

“It was bloody cold and we ended up spending a lot of time out in the cold that night and I wasn’t dressed for it,” he remembers.

The weather would be crucial to solving the crime.

“I don’t know what we would have done if it happened in the summer,” Graham says, standing atop the abandoned, elevated rail line that skirts the marshy Rideau shoreline.

He points, halfway down the bank below him.

It is the spot where Heather Fraser was pushed, perhaps thrown, onto the ground. Investigators found a large swath of matted snow, red stains and one mitt.

They had quickly found the isolated crime scene by following two sets of tracks, the only footprints in the sprawling park.

“It was like virgin snow,” Graham says. “There were no other footprints in the snow, so the only set of footprints into the scene were hers and his.”

At roughly 3 a.m., six hours after Graham was called away from his curling game, light snow began to fall. It could have been disastrous, but for the quick thinking of investigators, who needed to preserve evidence.

“We had to run down and get the manager of the liquor store to open the liquor store up so we could get boxes,” Graham says. “The boxes were being used to cover footprints in the snow so they didn’t get eradicated by additional snowfall.”

It is no more than 20 feet from the scene of the attack to the rusting, 97-year-old railway lift bridge that once raised like a giant steel jaw to allow boats to pass.

Unused for decades, it is now permanently frozen at a 45-degree angle so that the massive steel trestle pokes skyward, as if to mark this terrible place.

•

It was about 700 feet from the Abbott Street sidewalk to the lift bridge at the western edge of the canal property.

Two solitary figures walking in darkness would have been nearly imperceptible from the road by the time they reached the bridge.

Once they passed under the steelwork and curved north behind the concrete abutment and the railway embankment, they were invisible.

They walked only a few feet more before Giff, still brandishing his knife, put his coat down on the snowy slope.

He put his hand on Heather’s breast.

He knew what he was doing was wrong but he was full of rage and could not stop. He wanted to humiliate his victim.

Heather begged him to stop.

Giff raped her.

He used his knife to mutilate her vagina.

He plunged the knife into her upper right chest, through her parka, opening a wound one and a quarter inches long.

She was stabbed a second time, in the back, below the right shoulder blade.

Believing he had killed Heather, Giff scampered up the embankment, tossed his knife away and walked north along the disused railway line.

He had underestimated the tenacity of his victim.

With blood seeping from her chest, Heather began to crawl on her hands and knees, back along the same route that brought her to the embankment.

She lost her mitts, but clawed through nearly two-foot deep snow toward the lights of Abbott Street, scraping the skin from her knuckles.

She cried out for help.

By 6 p.m., Giff was at his uncle’s home on Alfred Street, looking for Annette Rogers. He had something to tell her – something to show her. He stayed only a few minutes before he left the house to search for her.

Carolyn Fraser was worried when she arrived at the family’s Abbott Street house just after 6 p.m. to discover that her daughter had not come home from school.

Her husband Ian suggested the oldest of their two daughters had likely stayed late at school for sports or other activities.

Carolyn Fraser phoned Heather’s friends then jumped in the car and drove to the high school, then to the youth centre.

No one had seen Heather since 5 p.m.

The worried mother drove home, expecting to find her missing child.

By about 6:30 p.m., Giff had found Annette Rogers and together they returned to the Abbott Street park.

Standing at the top of a snowbank, Rogers heard faint cries for help, enough to convince

her that Giff’s unbelievable boast about committing murder was real.

“He told me to get down and come with him or he would finish the job, which was me and it was my fault he did it and so I was to blame that she was there and that we had to get out of there because now I was an accessory and I would go to jail,” Rogers recalls.

The pair returned to 58 Alfred St.

It was 6:45 p.m. when Carolyn Fraser returned home again to find that there was still no sign of Heather.

Ian Fraser figured mother and daughter had missed each other at the school. Carolyn Fraser got back in the car and returned to the high school. Shortly after 7 p.m., she phoned her husband from the school. Heather could not be found.

Ian Fraser decided to retrace the route his daughter likely would follow to walk home.

He walked north on Abbott Street. Thirty feet north of the swing bridge, he noticed something in the snow, to his left, on the Parks Canada property.

It was nearly 7:30 p.m.

“I ran to it and when I got there I saw it was Heather,” Fraser later told police (read Ian Fraser’s entire statement to police). “She was hunched over on her hands and knees with her head down as though she was crawling.”

Remarkably, Heather had dragged herself more than 600 feet, to within 50 feet of the road.

“I turned her over on her side,” her father told investigators. “I asked her what was wrong and she just uttered one word, ‘Stabbed.’

“She was deep in shock, because her eyes were bulging and wide open. There was sort of a gurgling sound in her throat.

“After she said stabbed, I had her head in my arm and I could see that her shirt was dark and could feel that it was wet. I’m not sure if I opened her coat, not sure whether I unzippered it or not. I think I unzippered it.

“Her slacks were part way down, about her hips.”

Fraser hesitated only a moment before dashing to the nearby road where he flagged down two passing vehicles.

Heather was bundled into the back of a stranger’s van and driven to the Smiths Falls hospital.

She was cold and pale but conscious when she was wheeled into the emergency department. Staff worked furiously to stanch the bleeding and stabilize her. She was X-rayed and an intravenous tube was inserted in each arm.

In agony, she thrashed and moaned.

She could not answer questions.

Just after 8:30 p.m., she was in an ambulance racing to the Ottawa Civic Hospital.

Dr. Brian Penney, her family doctor, was in the ambulance, along with a nurse, an ambulance attendant and a police officer. Penney asked Heather if she knew him.

She nodded.

He asked if she could tell them what happened.

Heather winced, thrashed and shook her head.

At 9 p.m., she went into cardiac arrest.

The ambulance arrived at the Ottawa Civic Hospital at 9:12 p.m.

Heather was pronounced dead at 1:02 a.m. (read complete autopsy reports)

•

In February this year, Jamie Giff told the National Parole Board, in a hearing at Pittsburgh Institution in Kingston, the minimum-security penitentiary where he is now imprisoned, that he poses no risk to anyone, after 24 years behind bars (By 2014, Giff had been transferred to an aboriginal healing centre in Quebec).

Giff asked for unescorted passes that would allow him to leave prison for up to 72 hours at a time, without supervision, to travel to London, Ont.

He wants to open a bank account, get a driver’s licence, visit Fanshawe College, the YMCA and the local mosque.

Giff married while behind bars and has converted to Islam. He prays five times a day, he told the board. He has earned his high school diploma and has been a model prisoner.

He claimed that he no longer objectifies women and that he has been free of drugs and alcohol for years and has contained his rage.

Annette Rogers does not believe it.

She attended the hearing, faced Giff and read an eight-page statement, the fifth such statement she has submitted to the board.

“Please, I beg you, he is not ready to be released,” Rogers told the board members. “His lies are so deep that you have to see his little bit of therapy is not enough to let him in society and society to be safe.”

She reminded them that after Giff was convicted, he threatened to kill Rogers and her family.

Giff faced other problems in convincing the parole board that he could be trusted.

In group therapy sessions, he admitted, for the first time, to mutilating Heather Fraser. He said he deliberately cut her genitals to make her scream in terror because she wasn’t reacting the way he had imagined in his violent fantasies.

After the admissions, Giff was diagnosed a sexual sadist, a perpetrator who takes pleasure in inflicting pain and suffering.

Before the parole board in February, Giff said his group therapy confessions were lies, concocted because he had been warned by other participants that if he didn’t admit to acts of which he was accused, he would be forced to repeat the program.

The parole board denied Giff’s request for unescorted passes.

In July this year, the warden of Pittsburgh Institution granted a year-long package of escorted temporary absences that permit Giff to leave the prison daily from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. to do community service work in the Kingston area with the Salvation Army.

He also gets passes for “personal development.”

•

Ken Graham recalls sitting in a restaurant with his wife in the weeks after the murder.

The killer had not yet been caught.

She scolded her husband for his distracted behaviour.

“ ‘You’re doing it again, you’re looking at people’s feet,’ ” Graham recalls his wife saying.

The determined investigator was inspecting the footwear of every person who passed through the restaurant.

He was looking for those boots, boots with a distinctive sole.

Police had photographed and documented the pattern they found stamped in the snow of the Abbott Street park.

At the arch was an oval that encircled the words, “Oil Resistant.”

The words, “Star Valenti” appeared below the oval.

The front of the sole was wavy ridges.

Police weren’t yet sure they had found those boots, or its owner, even though they had quickly compiled a suspect list.

Jamie Giff was not on that first list. It included known sex offenders. Giff had no history of sex crimes and his criminal record was primarily minor assaults, robberies and thefts.

“To me, this was outside the range of crimes that I thought he was capable of,” Graham says.

There were other better suspects, but Giff succeeded in quickly pushing himself near the top of the list.

For days after the stabbing, a police cordon remained in place around the Abbott Street property.

Patrol officers guarded the perimeter.

A young man and woman walking past approached an officer to ask what was going on.

The officer noted a distinctive pattern being left in the snow by the young man’s boots.

Though Jamie Giff’s appearance had changed – Rogers had cut off most of his long hair – he was wearing the same size 8 Tuf Macs (see Giff’s boots) that he had worn Jan. 28.

“The [officer] noticed his boots and said, ‘Hey, those prints look familiar,’ so he actually hustled him right in the car and took him right over to where we were doing our investigation,” Graham says. “His boots were taken off him and photographed and measured and then he was released.”

Though he could have refused the police request to inspect his boots, Giff co-operated.

The designs in the sole of Giff’s boots matched the impressions found in the snow, but there seemed to be a discrepancy in the

size.

Graham went to Toronto, to the factory of the boot manufacturer. He retrieved sample soles from every size boot.

The manufacturer explained that each size of boot had a distinct number of ribs on the bottom.

“The rib count for his size was consistent with the rib count that was at the scene,” Graham says. “So he very quickly became a person of interest.”

Giff was approached by police repeatedly but denied any involvement in Heather’s murder.

He refused to provide blood or saliva samples and refused to take a lie detector test.

“We started to focus on him more and more,” Graham recalls.

Thorough police work also paid off.

Because of the scope of the crime, the Ontario Provincial Police had immediately been called in to help the small, Smiths Falls municipal police department.

Officers created a grid and collected every bit of snow from the railway embankment at the spot where they believed Heather was raped and stabbed.

The snow was hauled to the OPP station, where it was allowed to melt and pass through filters.

The filters were carefully packaged and taken to the Centre of Forensic Sciences in Toronto.

“In my humble opinion, it was a gargantuan effort to come up with some evidence,” Graham says,

In an era before DNA testing, the snow yielded invaluable clues.

Forensic investigators found fibres that were later matched to a coat that Giff owned.

They also found semen.

And they learned that the man who produced the semen was a secretor, someone whose blood type can be detected in saliva, tissue and semen.

The blood type of the rapist was relatively rare.

That set off a desperate hunt for the bodily fluids of everyone on the suspect list. Blood typing would eliminate many of the names.

Giff’s family handed investigators what they needed.

While his mother was being interviewed by investigators, Giff came into the room and lit a cigarette. He put it out, left it in an ashtray and left the room.

The investigator asked Giff’s mother if he could have the butt.

“To give her credit, she is his mother, but she said she didn’t believe he did it but if he did do it, he should be responsible,” Graham says.

Saliva from the cigarette butt was from a secretor with the same blood type as the killer.

The net was closing around Giff, but police could not yet definitively place him at the scene of the crime.

“He did that himself,” Graham says.

In early March, Giff was arrested on an assault charge unrelated to the murder. He was being held in the police cells.

For more than a month, investigators had dogged Giff, interviewing family, friends, acquaintances and, of course Annette Rogers.

She insisted he was innocent, though Graham knew that she had information she was concealing. He could not extract it from her.

On March 2, an acquaintance of Giff’s mother called police to say they were picking on the wrong guy.

“Why are you focusing on him?” Graham recalls the man asking. “He didn’t have anything to do with it.

“He just found her. He panicked and he left her. He didn’t kill her.”

Investigators were stunned by the revelation.

Graham believed Giff likely had grown tired of needling by friends and family asking why police were so interested in him. The veteran officer imagined Giff had finally explained away the police focus by saying he’d been at the crime scene, so of course his footprints were there, and perhaps other evidence.

Graham realized Giff should be interviewed immediately.

He and another senior officer brought him from the cells to a bland little room barely larger than a bathroom.

There were three, vinyl-padded chairs and one desk.

It was March 2. The case was about to crack wide open.

Giff acknowledged that he was passing by the Abbott Street property on Jan. 28 when he heard what sounded like a scream. He walked out through the snow, he said, to investigate.

“Ya, I went back, to the bridge,” he told the two investigators, in a tape recorded interview (read the transcript of the entire interview).

He said he walked to the old lift bridge, under the steelwork and around the corner to the railway embankment.

There, he claimed, he discovered a girl.

“When I found her, she was laying, up on her side. She had holes in her chest and she had her knee up,” Giff said.

“Uh huh, did she say anything?” Graham asked.

“She didn’t say, she didn’t say any names. The only thing she said was, just said, leave me here to die.”

“So what did you do?” the officer wondered.

“Well, okay, yous got hair from somebody’s head, right?”

“Uh huh,” Graham replied, though he was lying.

“More than likely, it’s gonna be mine,” Giff offered.

“Why would it be yours?”

“Cause I picked her up,” Giff replied.

He claimed that Heather suddenly went limp and appeared to pass out and, with that, he realized that if was seen carrying the wounded girl out of the park, he would be fingered as the person who attacked her.

He said he got scared and ran.

Then, the wily investigator cornered his prey.

Graham asked Giff if he remembered anything about Heather’s clothing.

“Um, there was a green, ah, what you call em, canvas bag there,” Giff said.

The bag was under the railway lift bridge, he said, describing accurately the spot where police officers found it that night.

Police had never revealed publicly that they had found the green canvas bag. Graham knew, because there were only two sets of tracks in the park – those made by Heather and by the killer – that Giff had, in fact, been there.

He had him.

“Okay, Jamie, I have a, ah, I’m gonna have to tell you something now,” Graham said. “That it’s my duty to inform you first of all that you have the right to retain and instruct counsel without delay. Do you understand that?”

Giff muttered, “Uh, huh,” though he did not yet seem to grasp the gravity of unfolding events.

“I wanna tell you now that, ah, you may be charged with first-degree murder,” Graham continued. “Do you wish to say anything in answer to the charge? You’re not obliged to say anything, unless you wish to do so but whatever you say may be given in evidence. Do you understand that?”

The caution continued for another minute, until Giff interjected.

“What’s this mean, I’m under arrest or something?”

Yes, Graham told him, touching off angry denials.

“I don’t care if I go to jail, I didn’t do it,” Giff insisted.

“You want to give a statement about it?” Graham asked.

“I’m not giving no statements at all.”

“Okay, well under the circumstances Jamie I think that ah, I already cautioned you on first-degree murder and from what you’ve told me…” Graham said, before Giff interrupted him.

“I, I, I, I knew, I knew, I was, yous were gonna, ah, screw me for this,” Giff sputtered.

“Well, we’re not screwing anybody Jamie.”

“Oh, no, well I’m getting pinned for it right here.”

Giff said he would not give a statement until he had a lawyer.

“I fuckin knew I shouldn’t a said nothing.”

“Well you’re wrong Jamie,” Graham said. “If you had anything to say, you should have come forward right from the start.”

“Ya, I shoulda, but I’m not familiar with people getting stabbed. And I ain’t familiar with people passing out when they’re stabbed in front of me. What am I s

upposed to do?”

Giff was charged with first-degree murder and pleaded not guilty.

He was convicted after an eight-day trial and sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years. Because he did not testify, he has never offered a public explanation of the crime. He refused to be interviewed for this story.

Giff admitted, midway through the trial, to the rape and stabbing, in the face of mounting evidence including damning testimony of an undercover police officer.

The officer masqueraded as an inmate and shared a cell with Giff in a detention centre.

“I did her,” Giff told the officer.

•

Annette Rogers still cannot adequately explain to others, or to herself, why she protected Jamie Giff and failed to help Heather Fraser.

“I will always blame myself,” she says. “She’s lost her life because of me, because I stayed in hiding.

“She didn’t deserve any of this.”

Seemingly as penance, Rogers has taken on the role of Giff’s nemesis. Despite the anguish she suffers from constantly revisiting her dark past, she vows to attend every parole hearing and argue that he is too dangerous to ever be trusted or freed.