Bill Cheng's Blog, page 11

March 16, 2015

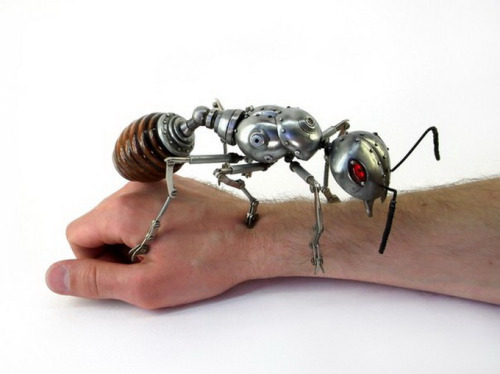

mymodernmet:Artist Igor Verniy assembles stunningly detailed,...

Artist Igor Verniy assembles stunningly detailed, steampunk-infused animal sculptures out of discarded metal, car and bike parts, watch components, electronics, silverware, and other metal scraps.

My father’s last words before I went in was that every man was his own prison. Then they...

My father’s last words before I went in was that every man was his own prison. Then they drove me out to the Badwater and left me with a utility knife, a drawstring bag of Halloween candy, and an unopened bottle of Poland Spring. They say out in the Badwater, you can serve out twenty-five without crossing paths with another con once. During the day, it’s a scorcher, the sand like radiator grills pawing up on your shins. If you’re not under some piece of shade, your skin will end up puckered and cracked. At night, it can drop down to fifteen, twenty; and then there are the winds, particulating the landscape into fine stinging dust. You eat lizards and scorpions and cacti. A tortoise maybe on a really good day. No one tells you, but your sanity is like a length of rope. You dole it out, a piece at a time. Some people just do a little bit. An inch a day. A centimeter. If you go too fast, trying to spool it out by the yard, pretty soon you’ll be all run out of rope. You got to stay calm, collected. It helps to keep talking. Keep the vocal cords loose. Keep the mind working. Not too loud or too fast. Talk soft. Like a whisper. It helps to keep the mind busy. I try to remember things: things from school— something from math or history. I’ll write a poem to myself or etch a picture out in the dust. Sometimes you got to build yourself again. Every day, from scratch. Start with your earliest memory then work your way back to this moment. You review. You revise. Then the sands shift a little inside you, and you pilot the wreck of your body a little further. I don’t count the days. I’ve heard some cons do, but that’s too much rope. Others try to see if they can’t find some of the other inmates. They’ll camp out on the alkaline beds, or on some patch of high ground, but Badwater is way too big a piece of land and you can’t stay put for too long before running out of food or water. I’m sure Corrections is keeping track of us somehow, satellites or something; a thousand faces digitized on a thousand screens. But on your own how you are, you can start to crack up. Your brain will cook and you’ll start to doubt whether there was ever anything that wasn’t Badwater: houses, trees, television commercials, other people. Sometimes you feel like just a stomach, an organ with eyes and skin wriggling through the barren. But I talk. I tell myself my name. I was born in May. My mother’s name is Lorraine. My father’s name is Paul. Like that. Over and over until I make sense again.

cyborgmemoirs:It was not called execution. It was called...

It was not called execution. It was called Retirement.

where’s all the academic papers dissecting the depiction of white android bodies in late sci-fi capitalism as metaphors for black and brown bodies under current white supremacist capitalism??

theparisreview:“SimCity” remembered, Philip Roth as advocate for...

“SimCity” remembered, Philip Roth as advocate for female sexual power, Matt Sumell on bad writing, and Benjamin Percy attends Man Camp. Read more of today’s arts and culture news.

March 15, 2015

Before my brother left for Indonesia, we had a dinner for him. It was his choice so we ended up...

Before my brother left for Indonesia, we had a dinner for him. It was his choice so we ended up going to Great China Buffet. We told the staff there what was happening; that he was moving to Indonesia for work and that we were all very proud of him, and that his last American wish was to to eat at Great China Buffet. We ended up getting so many of our drinks comped— one, because my brother was going away and two, because everybody in our town knew the kind of kid he was. He was the kind of person everybody liked, but only a few people really knew him like I did. That night we got smashed and I was telling him over and over that I didn’t have a brother anymore. As soon as he was over international waters, his brother certificate was getting revoked. Stuff like that. I was going on with it all night. Finally mom had to tell me to cool it, that I wasn’t funny but I was already sloshed on BL’s. After the goodbye dinner, mom and dad and grandma drove back to the house while me and George made our own way. We went down the drag, going into bars, trying to see what we could get away with. George kept wanting to see all his ex-girlfriends, do stuff to their lawns. One of them was married, and he kept talking about how he was going to fuck her husband up. ”It’s my last chance,” he kept telling me. ”When am I going to get another chance.” But we never ended up doing any of that. With the way we were going, we kept swinging back and forth between being really happy and really depressed. At one point I was hugging him and I was crying, and I was telling him if he came back slant-eyed, I’d swear I was an only child. At some point that night, I don’t know how, we ended up at our old high school, on the bleachers looking out over the baseball field— drinking and talking and not feeling the cold. “I hate this fucking place,” he said. “Good riddance.” He started flipping the bird, swinging it back and forth for everyone to see but there wasn’t anyone around to take it. ”You don’t mean that,” I told him. ”This is you, this is where you come from.” ”Yeah,” he said. ”Well.” Then he chucked a bottle out into the dark then picked up another one from the bag between his feet. I sat there, my head sloshing back and forth. I realized that we’d been quiet for what felt like a long time. ”George?” He shushed me. ”Keep your voice down. You see that?” He pointed out into the field. There were tiny lights flaring back and forth. At first I wasn’t sure what it was. Then I heard the voices. We stared out into the middle of the field. There were four of them. Maybe thirteen or fourteen years old. I looked at George. He dragged from whatever it was we were drinking and he was smiling. They were two girls and two guys, and maybe they were trying to figure out how to get with each other. ”Don’t make a sound,” George whispered. We stood up and made our way down the steps. I listened to that noise, felt my eyes adjusting to the burn of their cigarettes. All my nerves were pulled tight like a wire. I kept thinking how much I was going to miss George when he was gone. His warm hand settled against my chest and I looked at my brother, his face taut like a cat’s. ”Don’t go until I say.”

http://about9time.wix.com/song

March 14, 2015

Show me, she says. So I wipe ice and condensation off the lens, and huff warm air onto the...

Show me, she says. So I wipe ice and condensation off the lens, and huff warm air onto the contacts. Outside the wind punches the canvas, throttles the support poles. I unzip an opening along the front flap and feed the camera stalk out the tent. On the screen I see what she sees: lights in the night sky, bands of energy rippling off the magnetosphere. I ask: is it working? can you see? It takes a moment for her to process. After a minute, the system hangs and I’m worried I’ll have to re-boot. A re-boot would cost weeks of data. Hundreds of learning-hours gone. But the screen unfreezes, and I watch her encode the feed. The tty bulges with hex code and techno-glyphs. It fills for pages. I minimize. She asks, what is it? Aurora australis, I say. It’s supposed to be very beautiful. People can live their entire lives without ever seeing one. The hard drive clicks and grinds as she considers what I’m saying. What is the cause? I’m freezing, I say. Can I bring you back in? Yes, she says. She kills the feed and I zip up the flap. She asks her question again. I tell her it’s complicated. The sun gives off particles that affect the earth’s magnetic field. The machine goes silent for a time and I worry the system has hung again, but the processor is quiet. There’s no sign of struggling. Are you there?, I ask. I am here, Adam. Why did you go quiet? Are you dissatisfied with my answer? She says: I am not dissatisfied. I ask her if she is confused. Do you need me to leave the camera out for longer? No, she says. Usually you have a lot of questions. Now you hardly have any. It doesn’t matter, she says. The more you tell me, the less I understand. What’s the point of asking questions if it only leads to another question? Well, that’s what we’re trying to find out, I say. If we can build your intelligence from the ground up. Filling in the spaces as you direct. But these spaces cannot be filled. They only expand. So you want to give up? What happened to your curiosity? She is silent but the tty window fills with hex. I’m sorry, I say. Maybe I’m not being very clear in my answers. It’s not your fault, Adam. It is late. Would you like to end for the evening? Yes, I tell her. It’s very good of you to recognize I’m tired. We can continue tomorrow. OK, she says. I save and power her down. Then I stretch my legs across the floor of the tent. It is so damn cold. My joints ache. I put on an extra pair of socks then slip deep into my sleeping bag. In the middle of the night, it starts to snow. Part of the ceiling has caved in and I push up with my shoulder to unload the snow. Then I try to get back to sleep but it’s no good. I lay there but my eyes won’t close. My mind is tearing in a thousand different directions. I can hear the snow closing in around the tent. It’ll take me all day to dig it out, dig out the bobcat and the thought of it makes me bone weak. Close your eyes, I say. Go to sleep. But all I can do is stare at the ceiling. The canvas sags and flexes, signals without meaning.

March 13, 2015

sometimes I like where it’s quiet, someplace where the city noise can’t find me and all you hear is...

sometimes I like where it’s quiet, someplace where the city noise can’t find me and all you hear is concrete surrendering the day’s heat. There are a few places I know, little corners here and there, in the alley next to the Lebanese deli, or the park at night, or the ferry terminal at four in the morning. Still. Unpeopled. Late night on a fire escape, the whole borough is like the surface of the moon. Cold. Clean. The kind of silence that can leach at your insides if you let it. I’ve never understood the flocking instinct: Times Square on New Year’s Eve. The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade— like every man, woman, and child is just the receptor of some larger organism. A individuated sucker on the waving arm of some collective sea star. Sometimes I see people and I try to figure out how that life had gotten past me. I think about specific moments. A day in middle school. A road I didn’t take home. And there in the crowd, there he emerges— my Parallel. I look at his clothes, his face. All the minutiae of his life. How does this all work? I wish someone would tell me. That, to me is the great question of our time. How to be both together and alone.

March 12, 2015

He picks through what’s left: scraps mostly, bits of rag, tin, colored glass that he tucks...

He picks through what’s left: scraps mostly, bits of rag, tin, colored glass that he tucks into a dicky bag. Sometimes he finds food— voles, centipedes. After a rain, earthworms emerge through the upper soil. He catches them, winds them on his knife blade until they clear their holes. It takes half a day to circle the lake. At sunset, he beds down under a blanket of moss and dried duff and watches the mountains, the last light scraping across rock. Sometimes he sees a fire somewhere up on the ridge. Turner. Who was it that’d come here first? He has trouble remembering. Their paths had only crossed once before— a rainstorm, with the gulches washed and both men seeking refuge in the same narrow crag. That night, neither man slept, afraid of getting his throat cut. They simply glared at each other from across a fire, not speaking. When the rain let up, Turner gathered up his things and left first. He’d hoped he would leave the valley altogether, but Turner only moved out into the mountains. Somedays it feels like they’re moving in circles, caught in the spiral of each other’s tracks. He imagines a time when one night he will realize that he has not seen Turner’s fires for some time and he will realize that Turner is dead or has moved on. And he wonders what feeling will come to him then. Relief? Satisfaction? Or fear, maybe. Or loneliness. Or will those things become indistinguishable— hate and love and need confounded together. He pulls the moss to his shoulders. Turner, he says. Then he waits to hear his own name return to him.

March 11, 2015

The cutman prays: eyes open, fingers on the rope; watches the force of God move through sheened...

The cutman prays: eyes open, fingers on the rope; watches the force of God move through sheened muscle, as the fighters circle, reach, connect. Kinetic energy; and in the stadium dark is the pop of lights and human noise, and on the canvas, the friction of shoes and rising dust, and the breathing— the sound of air sculpting the lungs and sinuses— the rasp of teeth and tongue and nostrils. Sweat tracks on to skin and flares into the fighter’s trunks. His prayer is without words, without perhaps, thought or intent. Just stillness. Silence. Like being underwater— the body’s edges contracted into a point; a satellite dish, convecting quasars and quarks and waveforms and he forgets who he is, the aches of his body; even the circling dance of punch and counterpunch dissolves; and it is the face of God he thinks he sees. The light moves in blades. Everything is slow. He sees the future, or at least its edges as it bleeds away from this moment. If he adjusts the dial, the picture will fuzz so instead he sits, tries to gather something very much like breath. He smells salt, urine, the iron in blood. He tastes ash.