Katja Rowell's Blog

March 28, 2020

Impact of Past Food Insecurity

I’m hearing from foster care providers and adoptive parents. This highly anxious time, the disruption of routine, missing friends etc. is not surprisingly leading to increased food-seeking behaviors and anxieties, and a resurfacing of trauma. Perhaps a child is only a few weeks out from living in a food-insecure home, or they may have a decade or more of regular, reliable and filling meals behind them with a secure attachment. One mother wrote to ask about her teen who was adopted several years ago from a situation with severe neglect and food insecurity to the point of significant growth delay. Her daughter’s anxiety and food-seeking are spiking now, even after thousands of meals showing up like clockwork.

A history of neglect, food insecurity, dieting, or being restricted as a child can lead to anxieties and challenges into adulthood. If you or your children are experiencing increased anxiety and focus on food for any reason – bare shelves at the stores, media images around those bare shelves, or you’re having trouble accessing enough or your usual foods, I’m so very sorry you are going through this. I’ll share a few ideas specifically in this scenario for the mother of the teen, but that may help others:

Reassure her that her reactions are expected and common in times of increased stress and real (or even the hint of) food insecurity.

Stock up (not buy out the store of a 6 month supply) if you can on staples, on high energy foods, on her favorites.

Expect her to eat more, to look for food between meal and snack times, to favor her “comfort” foods. To eat when she’s bored. Try not to shame or blame when she does.

Ask her what might be helpful. Perhaps a granola bar on her night-table may help her know if she wakes up that she can eat. See how that goes.

Consider moving meals and snacks a bit closer together for a while. Try not to miss those times. Consider posting a schedule with times for eating and stick to it.

Consider offering her control when possible: baking, helping with menu planning, asking her for a few options for acceptable crackers or cereals, just in case they are out of his usual.

Don’t worry about vegetables for now. Focus on full bellies.

Touch base with her therapist if you have one. She may also be eating more as a means of self-soothing. This is not a bad thing. Recognize that food can give comfort and is one means of coping in this scary time. If she has other coping skills, include those into the daily routine.

Listen to her fears and concerns, or just the Tik Tok video she loves. She may not connect any of this in her rational/thinking brain to early food insecurity and that’s okay too. Expect her to “regress” a bit, or seek out more connection. Or, she might need time alone or with her friends online.

Include fun movement or walks, dancing, yoga if you can. Maybe some mediation apps or other tools you have for addressing the anxiety. Limit evening screen times if you can and focus on good sleep habits.

Don’t focus on weight or worry or comment about your or anyone else’s weight changes during this time.

Seek help if things worsen or you continue to have concerns.

And most of all, be kind to yourself and your daughter as you get through this. Remind her that she’s strong, you’re strong. You got through so much already, you will get through this too!

For more, check out my book, Love Me, Feed Me: The Adoptive Parents’ Guide to Ending the Worry About Weight, Picky Eating, Power Struggles and More

May 24, 2019

Healing Food Preoccupation and Trusting Hunger and Fullness

Mom read my first book, Love Me, Feed Me and we had one phone call to answer questions. (The book is “for” adoptive and foster parents, but is the same work I do with children who come to their families by birth.) A few points to note:

When transitioning from a control to a responsive, trust approach, eating will likely get worse for a short time before it gets better.

Children who ate any and everything may become more picky when they don’t feel the compulsion to eat.

Sweets preoccupation is generally improved by including them regularly and reducing shame around these foods. (Browse through blog posts here, just search “sweets.”)

Eating can feel soothing. Sometimes eating for comfort is okay. This mom recognizes that and is also building the child’s toolkit for self-soothing.

Children who have had a rough start can be trusted. Children can be fed in ways that bury internal regulation skills, or in ways that support them.

“The first few weeks were CRAZY!! There was a lot of gorging and never-ending eating at meals and at times it felt like all they were doing was eating. BUT…. Oh my goodness what an improvement since! Yes, there is still some insecurity around food, which I suspect may not ever completely disappear, but there is a lot of security as well.

As you know, my younger daughter would eat so much (did not ever know when to say enough) that she would cry because of her full tummy. Now she will really say when she doesn’t want any more and she’s full – and this could be after only half her plate is done or after 2 plates so it is a sign of her starting to listen to her body. Where before she would eat anything in front of her, now she is becoming more discerning. Which is a huge improvement. The other day I offered beet salad which she hadn’t had before, and she said “I’ll try a piece” tasted it and said, ‘No thanks, Mama I don’t want that.’ That is huge – for her to say no to any food.

I have seen a lot of improvement with my older daughter as well. While she also has struggled with portions – she’s the one with the super sweet tooth. When it came to any “forbidden food” she would not be able to concentrate on anything else. We have been following the having ‘forbidden foods’ every day and not making it ‘special’ and we have seen how, slowly, it’s becoming normal to her and not that absolute obsession.

Birthday parties have become less stressful too. We have realized that she is a comfort eater so when she feels anxiety she feels that food will help her cope – e.g. she gets extremely anxious in a new environment and will start looking for food. We are working on helping her find other ways to deal with her worry, like maybe we can talk to someone to make us feel better, or we can hold on to something special that helps us feel calmer (like her teddy, deep breaths sometimes help etc. She still talks a lot about food – not in ‘I want this or I want that” but she will, for example, always ask us what we had for lunch at work etc. That’s ok, it’s where she finds comfort and we are just continuing on our journey.

Generally, the greatest part is when we are out and they have something they love in front of them – like fries– and it isn’t a frenzy to just eat eat eat. They will not take a few bites and run off to play then come back for more etc. Secure that they can move away and still have their needs met later.

I can honestly say that, while before we were always on edge around food, now it just is what it is and it’s actually a huge relief. Almost seems that when we let go of it in our minds, the whole perspective changed, including our kids’ perceptions. What a mind shift and I’m so glad we did it now!”

Thanks for this mom for sharing her journey! See my series on Max and on the Worry Cycle for more information (NACAC Beyond the Stash article is a resource you can forward to caseworkers, clinicians, etc.) Learn as much as you can before jumping in if you are dealing with this issue. Generally, the younger a child is, the easier this process is, and the less time it takes to see progress. This family has been working on this for a few months…

Hang in there and good luck!

June 10, 2017

My kid gets dessert every night and is still obsessed with sweets!

A few moms this week have emailed to ask about sweets. Both have similar stories, and I’ll try to give a general answer here as this comes up often.

Paraphrased concerns:

“We eat really well at home, almost all whole grains, very little if any processed sugar, whole fruits and veggies. My kids enjoy a good variety of foods. We do allow one treat a day. The kids get to choose when they eat it, but it’s all they talk about. Also, when they have access, they have trouble controlling how much they eat. It’s not just candy or cake, but white bread and white rice, which we don’t eat at home…”

A few quick thoughts: I’ve seen many resources for parents advise that children get one treat a day. If this works for your kid, great! Congrats! However, what I mostly hear about are parents dismayed to find out that their child is lying to them, not fessing up to the cupcake at school, or finding treats on the school lunch debit card printout when the child swears he isn’t ordering those items. In my experience, a strict one treat a day rule sets kids up to have to lie to get the foods they want.

I’m not sure why some kids are okay with one or no sweet foods a day, while others are more interested… Probably a combination of factors; just like adults, some kids have a sweet tooth, others prefer potato chips. Some kids seem to melt with pleasure with a treat, and others don’t really seem to get much pleasure from food at all. And, a big factor is restriction. There are many studies that show that restricting access to sweets (or other things for that matter) often makes children crave them even more. And from personal and client experience, allowing children access, within structured and balanced meals and snacks often lessens the child’s interest. (For a great summary on the idea of food addiction, check out this post by Evelyn Tribole RD.)

When I first started out with M, I used the “one treat a day” approach, and it seemed to work for a while, mostly as all her food was consumed at home or sent to daycare or preschool. As she got older, and as the black market for sweets heated up at school, and the opportunities for treats increased, I noticed she wouldn’t mention treats that she had and I knew I had to adjust my approach.

Over the years, her interest in sweets has gone up and down. When it is up, I decide to allow more than I might otherwise feel comfortable with. She doesn’t have to lie. So the reality is that most days she gets 2-3 sweet items in an otherwise balanced intake, during meal and snack times (except occasional candy between meals, and occasional sneaking is developmentally expected.) So breakfast might be popped popcorn with butter and a little sugar, with fruit and milk. She might pack two Oreos with lunch (as often as not they are traded for chicken drumsticks or come back uneaten) and she might get a popsicle or cookie for dessert with dinner. Lunch is often left-overs, includes a fruit or veggie etc. Sometimes there is no dessert.

This may be more sugar than is “ideal” (though I imagine about what many of us had as children, remember when school cafeterias served ice-cream!!!), but I also see her leave half a piece of cake because she is full, ask for “as many vegetables as you can cram into that stir-fry”, and be able to enjoy outings and not obsess over sweets. Her growth is stable, and she has many opportunities to move her body, and gets lots of good sleep. Meanwhile a friend came over to bake, and she literally ate sugar from the sugar bowl. Many clients share that their children have been found sneaking and bingeing on treats at school or with friends. Helping children be able to relate and manage those high-interest foods takes some trial and error, and may look different for different children.

But here are some ideas:

Perhaps serve more than you might otherwise like to for a time. I view it as “innoculating” them against out-of-control behaviors that are common, and I believe set kids up for binge eating problems.

“Some days there are no desserts, some days we have three. It balances out.”

Don’t diet, shame, or tease around certain foods (or weight). Young children can feel shame enjoying treats (as young as four), and shame and deprivation are implicated in binge cycles.

Serve dessert with dinner.

If they don’t finish dessert, or they seem to slow down, let them save it for later, even breakfast! “Looks like you are getting full. Would you like to save the rest and have it with breakfast?” Having ice-cream or some cake with breakfast feels really cool! With milk and some fruit, it’s good energy to start the day. Be matter-of-fact when it’s happening. This has seemed to make a big impact for us.

Limit any nutrition talk that might spoil their enjoyment or bring shame into eating, limit nutrition talk in general. If the lectures haven’t helped so far, they probably won’t, and might make matters worse. Nutrition talk needs to be age appropriate, and in general, less is more.

You do get to say “no.” “I’m sorry you’re sad we’re not having ice-cream now, we had DQ for snack and we will have it again soon.” (See post below from Disney incident…)

If they are preoccupied with a food, consider bringing it into the rotation. Serve bagels every few weeks, or make white rice every fourth time you make rice. Avoid setting up certain foods as “bad” or “good”. Serve the bagels with a favorite veggie or fruit.

Try a dry-erase menu board, where you can write down what’s for dinner and dessert for a few days in a row, may stop the pestering.

Occasionally let them have as much as they want. Link to Ellyn Satter’s Forbidden Foods guide on the “treat” snack. (And Halloween how-to.)

Those are a few thoughts. Not easy stuff for sure, especially in a culture that makes so much money on disordered attitudes around food and bodies. Good luck! Oh, and I talk about this and much more, including the research that I found most compelling in my book, Love Me, Feed Me.

Some old related posts for fun:

Disney cruise where our waitress brought my kiddo a sundae for breakfast…

How permission helped one mom get a grip on sugary cereals

Putting treats out of site doesn’t mean forbidding them

A mom shares her Halloween success

Max’s healing from food preoccupation series, including an M&M a-ha moment in part 1.

July 20, 2015

Study on Kids and Weight: The Missing Piece of HOW Kids are Fed, or Restricted

I was curious to read this study, Eating Habits Matter Most With Overweight Children but was surprised that restriction wasn’t taken into account. (I have only read this article so far. This is a quick post with musings on the topic.)

“Our results show that in relative terms, the BMI of children who are particularly triggered by food increases more when compared with others. But we also found the opposite effect: a high BMI leads to children becoming even more triggered by food over time (at around 6 to 8 years old). As they get older, they are even less able to stop eating when they’re full,”

and…

“…many of these children find it difficult to know when they are full and therefore need their parents’ help to regulate their food intake (for example, one serving at dinner).”

I wish their findings had been examined through the lens of restriction, that is parents trying to get the child to eat less to weigh less, or to prevent weight gain. There is research that restricting children is associated with increased EAH (eating in absence of hunger) and higher BMI. And restriction can trigger more interest— thinking of a study I read once with Kindergarteners given graham crackers restricted to certain times and amounts. Result: the children were WAY more interested in them throughout the day (and ate more) than when they were simply available without comment or restriction. Studies comparing overt (“You’ve had enough!”) and covert (not having certain foods available) restriction add to the puzzle, but I would love to have seen more discussion about restrictive feeding in this article.

My take? Children who are restricted from early on are not supported with the developmental task of self-regulation and the process is sabotaged and the skills are buried (not lost I believe). I believe this phenomenon may be at least partly (if not wholly) what the study is describing. (Setting aside for the moment, the problematic labels and categories of “normal” and “overweight” in the first place, this study does seem to look at trajectory over time.) And there is controversy about what comes first, the large appetite, or the restriction, but I would argue large appetite when supported with responsive feeding is not problematic…

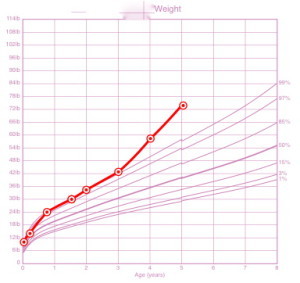

What I see most often with clients is the infant or child with the hearty appetite, who may be larger than average, then someone sounds the alarm about obesity (I’ve had a handful of clients who were exclusively breastfeeding told by MDs to cut out nighttime and other feedings for 4 and 5 month old babies who were “obese”…) Parents then restrict (or the parent restricts from the start worried the child will be “obese”), and the child who was growing steadily, perhaps larger than average, becomes very interested, preoccupied, or ‘obsessed’ as many parents call it, and then the weight acceleration can really take off (as it did for this child).

This study summary seems to further the idea that bigger children can’t be trusted to self-regulate, or that we should worry about larger appetites and children who find food pleasurable. It seems to encourage parents to restrict children in the name of teaching portion control since it implies these children are not capable of knowing when to stop. (Ironically, many of the parents of children with extreme picky eating that I work with are often told that their children are incapable of sensing hunger and are told to push food on their children…)

I think the parallels of adults and dieting and the flip-side of tuned in eating can help adults empathize. What do adults think about on diets? What did you think about on your last diet? (Mine was about 15 years ago on South Beach, and I was obsessed with having a bowl of cereal, but I digress…) Adults become preoccupied with thoughts of food, and tend to disinhibit (those four bowls of cereal on day 10 were ah-mazing!) Adults may have enough social graces and cognitive control not to pester everyone around them and beg and whine for food all day like a toddler or preschooler might…

And finally:

“…we know that in order to promote the development of normal eating behaviour, it is important for children to decide how much they want to eat. If children are pushed to eat everything on their plates, they may stop relying on their own body’s signals, and eat until the parents are happy.”

The author acknowledges that allowing children to decide how much to eat promotes normal eating behavior. Making children eat more than they are hungry for, she warns, can drown out the body’s signals. Why is there such resistance to the idea that making children eat less than they are hungry for also means they can’t rely on signals coming from their own bodies? I welcome research and discussion in this area, but worry that studies like this may lead folks to a false conclusion that makes matters worse, not better.

We CAN trust children with hearty appetites and larger bodies to tune in to hunger and fullness cues.

For more: I did a series about Max, a 3 1/2 year-old client with food preoccupation and how it was the restriction that fueled it, and responsive feeding through the Division of Responsibility that allowed the child to self-regulate and no longer obsess about food.

I could write more about this article and statements I found problematic, but I think this is enough for today!

I’d love to hear what others thought about this summary. Please join the discussion on facebook.

April 22, 2015

Extreme Picky Eating Help is here

It’s been awfully quiet around the Feeding Doctor’s blog… For the last few years I’ve been working on writing and now marketing Helping Your Child with Extreme Picky Eating: A Step-By-Step Guide for Overcoming Selective Eating, Food Aversion, and Feeding Disorders launches (officially) May 1. If you order now, your copy will ship in the next few days!

Jenny McGlothlin SLP is my coauthor. She developed and runs the STEPS feeding program at the UT Dallas Callier Center for Communication Disorders. Jenny is not only an award winning therapist, but a teacher and champion for children with extra needs. I was able to shadow Jenny at work recently, and every interaction I saw confirmed that she is a qualified, compassionate, and skilled clinician. She educates and examines, hugs and supports. I could not have asked for a better person to work with these past several months.

Working with children with extreme picky eating, I saw worried, often exhausted, confused parents trying to do as directed, and getting nowhere. Not only were their children not getting better in terms of their anxieties and accepted number of foods, but the strain on the parent-child relationship was often severely tested by the battles at the table. First and foremost, Jenny and I wanted to create a resource for parents that would hold at it’s core the precious relationship between parent and child and the need for parents to nurture, nourish and bond, not to bribe or distract. We include discussions of typical development, why children struggle, and how parents and children find themselves in unpleasant and counterproductive feeding struggles. We then give a step-by-step process to turn around the anxiety, restore peace to the table, figure out what to serve, when and how, and how to gauge progress and determine if and what kind of therapy may be warranted.

Please check out www.extremepickyeating.com for more information (where I will be blogging for the time being) and as always on Facebook where I will share general feeding links, articles and random findings that pique my interest, or my ire.

Here are a few reviews of the new book!

Katja Rowell and Jenny McGlothlin have crafted a book that provides very specific suggestions to help parents both understand and address their picky child’s eating. It belongs in the library of every parent and therapist who wants to support a child’s (and a family’s) positive relationship with food and mealtimes.

Suzanne Evans Morris, PhD, SLP New Visions

Rowell and McGlothlin expertly illuminate the complex emotional world of children with extreme picky eating and the caregivers who struggle to feed them. Helping Your Child with Extreme Picky Eating is a masterpiece of practical strategies, compassion, and reassurance perfect for parents, pediatricians, and anyone who remembers hating ‘just one more bite.’

Jessica Setnick MS, RD, CEDRD pediatric eating disorder specialist, cofounder of the International Federation of Eating Disorder Dietitians, and author of The Eating Disorders Clinical Pocket Guide

Sign up for the newsletter here.

Follow extreme picky eating help on facebook

November 4, 2014

Halloween Joy, and What are You Afraid of?

I wanted to share this email (with permission) from a former client. We had two calls a few years back addressing her concerns about nutrition and higher-than-average (but healthy) weight and appetite.

Note the contrast between anxiety and the sense of calm enjoyment.

Hi Katja,

It’s Halloween night and our whole family had such a wonderful time! Halloween is fun for our family and we are not full of anxiety. Maya and Andre (5 and 7) got home from school and into their costumes. The candy was in a huge basket by the door, but they didn’t have any because they knew they’d get some later – they didn’t beg or sneak or whin

e. They ate dinner and waited for friends and then ran around the neighborhood gleefully collecting candy. It was cold outside and so they were the ones who decided they had collected enough and wanted to go home. They came in and sat in front of the fire place and dumped out their candy in a huge pile. They ate some, spit some out, traded some, shared some with us, dumped the things they didn’t want back into our big basket and then packed it back into their bags and headed up to bed when we said it was time. Seriously, it was that easy. They fell asleep within a few minutes. I actually think they got more exercise tonight than they normally do on a school night. They ran and ran.

I was thinking about how this is many kids’ favorite holiday and we talked about how many adults ruin it. On the playground after school this week, I heard lots of anxious talk from parents: “What do you do about candy?” “We buy it from our kids,” “I only get natural suckers from the coop,” “We have a candy fairy come in the night who takes all the candy and leaves a toy,” “If we didn’t take the candy, our kids would be obsessed. They would never forget about it and they would eat it all.”

I am so relieved that I have a plan that works so well for us. Halloween is FUN! They kids don’t actually eat that much sugar and they feel in control and not deprived. It feels great for us as parents not to be on their case and fighting with them. It’s great to be able to avoid that power struggle altogether. I will add that part of what really helped us tonight is that at one of our last stops along our trick-or-treating route, there was a family grilling burgers and brats in the front lawn. It had been awhile since dinner and the kids gobbled them up. I’m sure that made a huge difference in how well bed-time went. It’s a great reminder that offering a balance of foods is important.

I’ll stop rambling now, but I just wanted to let you know that your hard work really does make a difference…”

How does it feel?

Responsive feeding and parenting is at it’s core (to me) about how it feels in the moment with your child and how your child reacts, whether we are talking about buying their candy, or enforcing a “no thank you” bite rule. In workshops, I ask parents to reflect:

How do you feel in this moment?

How is your child responding?

Is the dynamic bringing you closer to your child, or increasing conflict?

Is the dynamic increasing anxiety or power struggles?

Use your anxiety, worry and weariness of conflict as your guide. If there are areas you worry about, where the anxiety spoils parenting or meals, that’s an invitation to learn more, and an opportunity to find the right help. Do you really need to worry? (For example, almost all of the nutrition analyses I have seen for children where protein intake was a concern showed children consuming more than enough protein…)

Conversely, when parents express relief, and a sense that a new approach feels good, you can trust that intuition, or at least consider it in your decision making process.

Is your current approach helping or not? What are you afraid of? What other ways could you address your worry and enjoy your kids and your family more…

Where have you learned more and worried less, with good results?

October 15, 2014

Part of a “Complete” or “Good” breakfast?

I remember watching Saturday morning cartoons in the late ’70s. The cereal commercial barrage always ended with, “Part of a complete breakfast!”

That complete breakfast included juice, milk, cereal, toast and butter and some kind of fruit (or a close variation). It seemed like a wholesome spread! You’d have to sit down for that meal.

Recently I caught an ad for a ‘sugary’ cereal and the phrase was changed to “Part of a good breakfast.” The meal included: cereal, milk and an unpeeled clementine.

I’m fascinated by the change. What stands out immediately is how much less food there is: no butter and the filling whole wheat toast is gone, and orange juice has too much sugar for our ‘modern’ nutrition thinking and would never appear on an ideal breakfast. (I’m not saying kids needed to eat all of the choices from the ‘complete’ photo, but to be able to choose from sources of fat, protein and carbs is balanced.)

What are your theories for the change? Is this another byproduct of the war on childhood obesity? Cutting calories? Recognizing that few families sit down to a spread most days?

Then this came along, from the New York Times on what children around the world eat for breakfast. Now, having a photographer in your house might mean you make an extra effort, but what struck me was that many pictures showed several choices for the kids— little pickled dishes in Japan, cheeses and olives and more in Turkey… Yummo!

Now THAT’S a complete breakfast!

Tips for picky eating

Add more choices, don’t take away.

Think outside the box. Leftovers may be a perfect “breakfast” food.

Serve breakfast family-style, add a small bowl of frozen blueberries, or other choices…

Put your scrambled eggs, or quartered bagels on a plate in the middle of the table too.

You never know when she’ll be ready. Remove obstacles to trying.

I also noted how the child in Amsterdam from the NYT piece enjoyed white bread with butter and chocolate shavings, and that sprinkles are a breakfast staple. Yet we aren’t inundated with stories about obesity and horrible eating habits in the Netherlands.

Maybe a “good” or “complete” breakfast varies from country to country, child to child and day to day.

Just some breakfast musings.

July 14, 2014

Kitchen Essentials and RV Livin’

In nine days, my family and I will embark on a grand adventure. We are taking the opportunity for a mid-life (we hope) reboot and hitting the road to live, travel, cook, home-school and all the rest in a 38 foot used RV we picked up a few months ago. We’ll be gone a full calendar year. I’ll be able to write and continue to work with clients by phone, though I don’t imagine I’ll be able to do any house-calls from the road (unless you are in the same state park…).

While I’m focused now on packing and getting ready, the one thing I am most curious about is how I will adjust to cooking in a kitchen with about 2 feet of counter space and an 8 cubic foot fridge, which is much smaller than my Twin Cities home fridge.

Our main challenges are space and weight. We don’t want to burn out our axles (apparently). Our indoor kitchen has three propane burners, a small oven and a microwave. We will have an “outdoor” kitchen with a small propane grill and two burners and a small fridge.

Things I will miss: knowing the grocery stores I shop at, having a Whole Foods, Target and local coop within three miles of my home, my basement freezer, my stand-mixer, the rice-cooker, roomy pantry, my food-processor for making smoothies…

I will bring my large crock-pot that has a simmer feature, our air-popper since we make a lot of popcorn for snacks and it’s not too heavy, my hand immersion blender, two-slice toaster, two silicone muffin pans, one 9×9 Pyrex baking dish, one Pyrex round casserole dish with top, and the standard gear like a peeler, spatula, wisk, paring knife, Santoku, these grippy cutting mats…

So, my question to you is…

What gadgets would you take with you, what would you be able to live without, how would you replace them (i.e make rice in the slow cooker which I have yet to perfect)…

What essential pantry items/spices would stay, what could you live without?

When we moved the last time, I had two laundry baskets full of sauces and stuff, and there just isn’t room. For example, I plan to only bring 2 vinegars: white balsamic and cider— okay, maybe three and bring the rice vinegar…

You see what I’m up against? Help!

Any tips (or favorite resources) for shopping, pantry and cooking with small spaces and likely with some weeks in “food deserts” are welcome! I figure we may be eating more dried fruit and frozen fruits and veggies…

June 25, 2014

Learning to Tune In: Part 5 Food ‘Obsession’

This is the final of a 5 part series. Read Part 1: Healing a Child’s Food “Obsession”: Max’s Story

Part 2: Is My Child “Obsessed with Food? and Part 3: What Are You Worried About? and Part 4: Trying to Get Kids to Eat Less Backfires.

The Trust Model (division of responsibility) is healthy feeding and was described as “responsive feeding operationalized” in the Journal of Nutrition and Education (2011). You provide, plan, and feed so your child can let go of the anxiety, fear, and worry that is making it hard for him to tune in to his internal cues and eat well, and to just be a kid… This long post is a brief introduction to a complex process of supporting food preoccupied children so they can learn to tune in again (or for the first time). What this process entails is often a complete shift in thinking and approach to feeding. Not easy.

Guiding Principles

Follow the DOR. You decide: what, when, where. Your child: how much from what you provide. And:

Accept your child as he is right now.

Try not to focus on your child’s weight.

Focus on behaviors, such as sitting down for breakfast or not grazing.

Establish and maintain bedtime routines and aim for adequate and regular sleep.

Provide the opportunity for regular, fun movement.

Meals and Snacks

Serve a small portion of dessert with the meal.

Two to three times a week, serve a “treat” snack that includes “forbidden foods.”

Eat meals together if you aren’t already.

Serve family style: put all the food out in bowls.

Be sure you have plenty of food.

It’s okay to say “no” if there isn’t enough to go around, or if a food is expensive. Your child can satisfy his hunger and appetite with other foods. “I’m sorry, there isn’t enough steak for anyone to have seconds, you can have more potatoes or salad if you’re still hungry.”

Serve regular meals and snacks—every two to three hours for younger kids, every three to four hours for by around Kindergarten.

You can end meals at around 30-40 minutes (you don’t have to let them sit and eat for two hours.) “In five minutes, we’ll go play Legos.” (Rather than, “Dinner is over, you’ve had more than enough.”) He might try to eat a lot and quickly when it’s time for the meal to be over. in the beginning.

You don’t get to forget a meal or snack. You remember it so they don’t have to worry about it.

Make snacks balanced and filling. Yes, offer her more—even if you worry about weight. When a child can be satisfied in terms of hunger at meals and snacks, she can stop thinking about food until the next time to eat in a few hours.

“Snacks were supposed to be 1/2 cup of plain fruit or vegetable. She would wolf it down and want more. I think she was really be starving by the time dinner came around and she would eat fast and beg for more. There were days I could control her eating, and then others where she ate massive amounts. I never understood how my chubby child was always saying she was hungry.” — Kayla’s mom (Turns out the intake analysis proved what mom was observing with some days around 900 calories, and others closer to 3000. Interestingly, her weekly average was within the recommended range even though her BMI was in the “overweight” range.)

Include low, medium, and high-fat choices.

Don’t “accidentally” run out of the high-calorie, or “red-light” foods.

Don’t try to skip snacks or meals if she is busy doing something else.

“I was told to lie to the kids by our RD (dietitian). It felt absurd. My kids were smarter than that. They figured out that I only ‘ran out’ of the stuff they really liked and wasn’t supposed to let them have, like rice, pasta, meat…” —Leah, mother of two

How the Process Usually Unfolds

Once parents institute structure, family meals and the DOR (critically, allowing the child to decide when he’s had “enough”), this is how the transition, which can be divided into two general parts, typically unfolds with clients.

Stage One: “This Is So Scary”

Predictably, at first he will likely eat more. A lot more. (See the first several sections of Max’s Story.) This is when, without proper preparation and support, most parents panic and give up. Many parents I hear from have already “tried” to let the child decide how much and couldn’t get through the transition. It was simply too scary. Stage One is called “This is So Scary” from the parent’s point of view because it’s mostly about parents’ fear of weight gain, uncontrolled eating and doubt that their child is capable of knowing what ‘full’ is. There are also a lot of practical questions about how to apply this model that come up day to day.

Amy, mother of Teresa, age four, wrote on my blog, “We did it for four days, and I couldn’t stand it. She ate more than my husband, so we went back to preplating her portions.”

Try not to react to how much she is eating. Your child will eat more than you are comfortable with. Don’t count slices of bread or pizza, and don’t comment. This is tough. You will want to chime in with, “That’s your fourth piece of bread. Honey, aren’t you full yet?” It won’t help, and it could make her want to eat more. It distracts from her internal cues. When you pick her up from a party and her friend’s mom says with a frozen smile, “She is such a good eater; she ate six pieces of pizza,” try to deflect attention and say, “Oh, I’m glad she enjoyed it, sounds like it was a great party. Thank you.” Avoid explaining or apologizing in front of your child. Stay calm and send your daughter the message that you trust her, and she will figure it out.

While in stage one and still eating a lot, children may rather quickly become less anxious, and more calm at the table and maybe away from the table as well. He may seem happier and more playful. This is the progress you want to watch for in Stage One and it is critical, the basis for all other progress.

Another child, two weeks in, shows signs of recognizing what it feels like to be full, leaving food, and leaving the table without extraordinary measures. “Today at lunch, she didn’t eat much, asked for more of something, then as soon as we gave it to her, she said she was done. Another day, she left the table voluntarily to go play, something she had never done in her two and a half years.”

‘Normal’ in the Transition

Knowing what is ‘normal’ will help you get through it. During the transition, your child is aware that things are different and is trying to figure out the new rules, asking if she can have more chicken, even with chicken already on her plate. She is learning to trust that she decides how much to eat from what you offer and that she doesn’t have to be preoccupied about when she will eat next, because you are being reliable about that. This will all help her learn to tune in to cues from her body, instead of being ruled by anxiety and that feeling of scarcity. The younger the child is and the more able parents are to stick with it, the faster the transition usually goes. For my clients, with young toddlers, Stage Two can come as early as a few weeks in, and often by two months, there are many signs of progress. Older children, or with more severe restriction may take longer. Preschoolers usually show progress in a few months, and within six months are well into Stage Two. Adolescents may benefit from their own support around food or body image issues. (Because of my practice model, most of my clients have been preschoolers or early grade-school.)

Stage Two: Emerging Skills

If parents can make it long enough to see even these earliest glimmers of self-regulation emerging, as well as less food obsession, it helps build faith in the process. Stage two is characterized by emerging skills, but he will still “overeat” and seem food preoccupied much of the time.

“Well, we went for a burger, and lo and behold, she had about half the bun, one bite of meat and said she was done. We were so surprised. I have learned that what she loved one day does not always mean she will like it in the same amount or at all the next— which is a change, because she used to eat anything and everything in large quantities.” — Alexis, mother of Greta, in Stage Two

More signs of emerging skills to look out for (and journal):

She is less frantic or preoccupied with food.

His rate of eating is slowing down.

He is playing with food.

He is opening up to the idea of sharing foods, as in, “This is for my brothers,” or “I had mine, that is Daddy’s.” (Even if he goes on to eat the food, acknowledging is step one.)

She may appear to savor foods more, rather than gulping or stuffing.

She will leave food on her plate.

He will leave a meal voluntarily.

She becomes more choosey about what she will or won’t eat.

He is consuming large meals but also smaller ones, as in, “He ate a huge amount at dinner, and it was really scary, but I noticed he ate less at breakfast the next day.”

She engages more with others at mealtimes, and plays at play dates and parties after checking out the food.

You begin to see patterns, such as more at breakfast or after nap and less mid-morning.

He is getting a little more “naughty” at the table. He’s not preoccupied with how much he can eat and is testing other limits like any other child.

Freed From Worry, Room to Play

Many parents report that once the child was less preoccupied with food, spontaneous play and movement increased on its own—even very early into the transition. The child who in June wouldn’t leave her mother’s side at the beach (because she was constantly begging for food) was running and splashing in the water by the end of summer. These children discover the playground when they are not wandering from one parent to the next for snack handouts.

Realize that people (kids are people too) differ with their level of interest in food. Some children will always eat faster or take more pleasure in food than others. (There are studies that suggest this is an inborn trait, with “picky” eaters showing different sucking patterns even as infants.) Clearly, some children get more pleasure from eating, and this is not a problem within the context of a healthy feeding relationship.

Remember also that these are emerging skills. She will still pester you about treats and perhaps eat quickly or “overeat” at times. In addition, many of these behaviors are normal for small children, and even the child who is eating competent will occasionally beg for treats and “overeat.”

“We were all still sitting at the table talking when she announced she was DONE and wanted to get down to go and play. I let her down with no comment, of course, but I was jumping up and down inside!!” — Rebecca, mother of Adina, age two-and-a-half

There is hope…

See my resources section for one page handouts (feeding tips for preschoolers sample) to fill in some of the blanks. Recommended reading, Your Child’s Weight, Helping Without Harming and my book, Love Me, Feed Me

If you would like to join a new private facebook group for parents (moderated to be a safe space), send a “friend” request to Bon Appetites (little girl with pony tails) and you will be invited to join the group (and then she will promptly unfriend you). She’s not being mean, just protecting privacy.

Read Part 1: Healing a Child’s Food “Obsession”: Max’s Story

Read Part 2: Is My Child “Obsessed with Food?

Read Part 3: What Are You Worried About?

Part 4: Trying to Get Kids to Eat Less Backfires

Parts of this post are excerpted from my book, Love Me, Feed Me

If a young person is also dieting, or you suspect s/he is purging or is concerned about body image, you may be dealing with an eating disorder. For more information, visit NEDA’s website and talk to your child’s doctor if you are concerned.

June 17, 2014

Trying to Get Kids to Eat Less Backfires: Part 4 Food ‘Obsession’

This is part 4 of a 5 part series on food preoccupation. Read Part 1, Max’s Journey of Healing, Part 2, Is My Child Obsessed with Food? and Part 3 What Are You Worried About?

Health Care Providers Recommend Restriction

Like the rest of us, many clinicians simply aren’t aware of the research. They cling to simplistic ideas like, “It’s just calories in, calories out,” and the belief that cutting a few calories here and there adds up, like a math equation, to a certain number of pounds lost. But the issue is far more complex.

The vast majority of primary-care physicians get little training in nutrition and none in relational or responsive feeding, despite stacks of research. I did not know, and will admit to being ill informed when I was in clinical practice as a family doctor. I had to learn for myself, seek extra training, and even undo a lot of misinformation. I do not accuse my colleagues of bad intentions; I know they are dedicated, caring, compassionate professionals who really want what is best for children, but they are unaware, and this has serious consequences.

If you are a health care provider, ask yourself how it feels to practice in the current approach (decreasing calories, portion control, restricting access to highly-palatable foods, pushing exercise, focusing on weight…) Does it work? Do you dread talking to families about weight? Are you confident that what you are doing is helping and not harming? These were the questions that helped me approach this issue with an open mind. I was not satisfied with my outcomes with the standard approach, which both my patients and myself seemed to intensely dislike.

Clinicians, like the rest of us, tend to focus on what children eat and ignore how children are fed. They assume the child who is accelerating with weight is simply drinking too much sugar-sweetened beverages or eating too much fat or too many calories. Their approach most often will be one of cutting calories or trying to get the BMI below the 85th percentile, even if a higher number may be healthy for your child. One pediatric dietitian (RD) shared that the goal at the weight-loss center she worked at was for all children to reach the 50th percentile! (See Part 3 for thoughts about weight and BMI…) And, a handout with calorie limits, 60 minute exercise recommendations and a list of fat-free or sugar-free foods is faster for the time-strapped clinician than learning about and supporting the complexities around eating, feeding, meals and more…

One mother reached out after the RD she saw at a university-based pediatric weight loss clinic recommended diet soda and Crystal Lite as “preferred beverages” for her two-year-old. This felt wrong to her, and despite following the calorie and “red-light-food” limits for six months, her daughter became more food “obsessed” and her weight was accelerating.

A Diet By Any Other Name is Still a Diet

Most of us know that diets don’t work, and while most clinicians are more savvy and no longer recommend outright “diets” for children, they still talk about letting “weight catch up with height,” “portion control,” “green-light, red-light,” and other kinder and gentler descriptions. (Many clinicians still do recommend outright diets with strict calorie limits.) The bottom line is that if you are trying to get your child to eat less so she will weigh less, it’s restriction, it’s a diet, and it will almost always increase her interest in food and probably increase her weight as well.

Which of the following tactics have you tried or have been recommended to you?

Using a highchair tray longer than necessary to keep food out of reach.

Pre-portioning foods and refusing when she wants more.

Making the child wait 20 minutes before she can have more.

Distracting with toys, video etc. to get the child to eat less.

Pushing low-calorie, “green-light” foods.

Not allowing favorite high-calorie or high-fat foods (red-light foods).

Trying to fill the child up on water before eating.

“Running out” of favored foods.

Shaming or scary talk about health risks or fear of fat, praising or selling low-calorie foods.

Repeatedly asking the child if she is “full yet” while eating.

Making the child exercise a certain amount to cancel out calories.

Others?

These tactics backfire because they undermine internal regulation, or eating based on signals coming from inside the body regarding hunger, appetite and fullness. The parents’ job is to provide balanced offerings, at regular times, eat together, and the child’s job is to eat as much or as little as he or she wants from what is provided at those planned, sit-down meals and snacks. This is known as the Division of Responsibility. Things go wrong when the parent tries to do the child’s job (decide how much to eat) or when the child is allowed to do the parent’s job, or when the parent doesn’t reliably provide enough food.

Note: Some food “rules” seem to ‘work’ for some kids; temperament, genetics, history around food, pleasure from food, restriction etc. will determine how your child reacts. If one child doesn’t miss the “junk” food when it’s removed from the home, fine, but for the child where the removal and restriction increases the focus, pushing harder and limiting more is unlikely to be the answer.

For extra credit, here’s an article challenging the idea of food “addiction” from Evelyn Tribole RD, co-author of Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Program that Works.

If you would like to join a new private facebook group for parents (moderated to be a safe space), send a “friend” request to Bon Appetites (little girl with pony tails) and you will be invited to join the group (and then she will promptly unfriend you). She’s not being mean, just protecting privacy.

Read Part 1: Healing a Child’s Food “Obsession”: Max’s Story

Read Part 2: Is My Child “Obsessed with Food?

Read Part 3: What Are You Worried About?

Stay tuned for the final installation, part 5, Learning to Tune In…

Parts of this post are excerpted and adapted from my book, Love Me, Feed Me