Katja Rowell's Blog, page 2

June 10, 2014

What Are You Worried About? Part 3 Food ‘Obsession’

This is part 3 of a 5 part series on food preoccupation. Read Part 1, Max’s Journey of Healing and Part 2, Is My Child Obsessed with Food? This is a long post because the fear of fat and the consequences of that worry are so harmful, and that worry is the biggest barrier to supportive feeding…

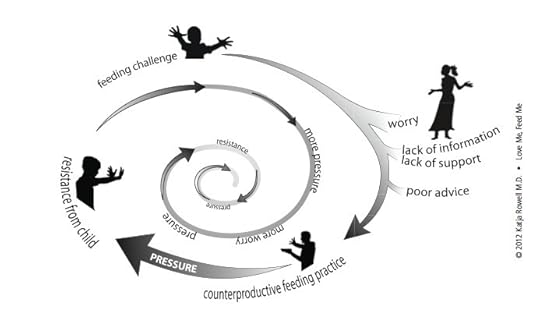

The food preoccupied child is anxious and works hard to get food. The worried parent keeps food from the child. The harder the child works to get food, the harder the parents have to work to keep food away, even resorting to padlocks on the pantry. The worry in this scenario behind the counterproductive feeding is almost universally about weight. The child is perceived as challenging to feed because he is “too big,” might get to be too big, or his appetite is “too big” (the worry is still that the big appetite will make the child fat)…

Parents receive harmful feeding advice from the experts they turn to, who are often unaware of the research and don’t understand that restricting children is harmful and can harm the feeding relationship. Trying to get a child to eat less, or banning “forbidden foods” can lead to a child who is preoccupied, eats more when she has the opportunity, and may weigh more than nature intended. First do no harm.

What Is “Overweight” or “Obese?”

Until we address the fear that drives the restriction, parents will have an almost impossible time trusting the child with eating. As Max’s mom shared in Part One, “I don’t think I can accept having a fat child… I worry about his health.”

When I use “overweight” or “obese” in quotations, I refer to the cutoffs and labels on the standard body mass index (BMI) and growth charts. The child growing above the 85th percentile is considered “overweight,” while the child growing at or above the 90th percentile is labeled as “obese.”

This girl is considered “overweight.”

This girl is considered “overweight.”

Are these labels meaningful? Consider:

In other countries, the cutoffs for “normal,” “overweight,” and “obese” differ. Does it make sense that a child at the 90th percentile in America is “obese,” but if he travels to England, that same child is merely “overweight?” They use different cutoffs. This is a clue that these labels are not necessarily clinically meaningful for an individual child.

A decade or so ago, the child growing at the 90th percentile was considered “at risk” of becoming overweight, and as with adults, the cutoff points and classifications were lowered. Overnight, almost 30 million American adults went to bed with “normal” and woke up “overweight,” with no change in actual health.

In a young child, five pounds can span the label of “normal” to “obese,” and 1/8 of an inch can change the “diagnosis.” While the clinical significance of a few pounds is questionable, the the label is not.

Labeling children has not been shown to improve health and is more likely to make your child less healthy. Regardless of actual weight, children labeled “overweight” or “obese” feel worse about themselves, exercise less, and are more prone to practice disordered eating, diet, and gain weight. Parents who are told their child is overweight tend to resort to trying to get the child to eat less, with more dieting and, ultimately, weight gain. “Knowing” is not necessarily a good thing.

Remember that a child growing consistently—even at a high percentile—is larger than the majority of her peers. But to label her as “overweight” when she may be healthy weight for her is wrong, implying a health risk that may not be there. (This article on assessing growth curves explains, “Many children who are otherwise perfectly normal exhibit growth percentiles at the extremes of the growth curves.” It’s worth a read.) Almost always, the child of the parents I work with is a larger-than-average but healthy child, enjoying good nutrition, with a lot of effort on the part of the parent. Then a worry, either from the parent or from a health care provider who labels the child as “overweight” or “obese,” sets off the cycle of worry, restriction, and food preoccupation, and often accelerated weight gain. Like Max, whose initial growth was perceived to be problematic in Part 1, with higher than average but steady growth, and resulting restriction.

What Children Weigh Now Does Not Reliably Predict Adult Weight

I cringe when families tell me that restriction and outright diets (and diet soda) are recommended for a child of two or three years. As larger-than-average children grow up over the years, they trend toward slimming IF they are supported well with eating and activity. (That is a big IF on purpose.) Child BMI is not reliably predictive of adult BMI. According to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, “a substantial proportion of children under 12 or 13, even with BMIs higher than 95th percentile, will not develop adult obesity.” (Note: There is increasing predictability as BMI increases, and the older the child.)

The youngest age at which I have seen restriction recommended was for four-and- a-half-month-old Mia, an exclusively breastfed baby. The pediatrician told Mom that Mia was “obese,” to cut out nighttime feeds, and to try to hold Mia off her feeding for 30 minutes when she seemed hungry. Within weeks, mom’s milk supply was down to nothing, and this family was on the road to dealing with a child with an increased interest in feeding. In this case, the doctor recommended feeding in a way that was not responsive to Mia’s needs (or her moms), which set up their feeding struggles.

“But, can my child be healthy if she’s above average weight?” This is the fear. I hear you. This was my main stumbling block as I was learning.

This section will seem to defy every cherished belief about weight and health that our culture and most medical practitioners hold true: The idea that every “extra” pound shortens your lifespan—that weight is linearly related with death and sickness. It is not. There are many healthy people at a variety of weights. Yes, some conditions are correlated (different than causation) with higher weights (mostly adult BMI of 35 or 40 and above), but in studies when fitness level and other disease risk factors were taken into account, the level of fatness did not predict disease. In addition, more research is confirming that health improves (as evidenced by blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol improvements) with healthy behaviors, even without weight loss. You can be fat and fit. If you are reacting strongly to this statement, you are not alone; I remember literally scoffing the first time I heard this.

My main point is that if you hear yourself saying, “Yes, but she can’t be healthy and be overweight,” I urge you to read and learn more. If you don’t believe your child can be healthy if she isn’t slim, it will be difficult to trust her and help her become a competent eater. The following books can help start the process:

Rethinking Thin by Gina Kolata

Big Fat Lies: The Truth About Your Weight and Your Health by Glenn Gaesser, PhD

Health at Every Size by Linda Bacon, PhD

Intuitive Eating by Tribole RD, and Resch RD

Your Child’s Weight: Helping Without Harming by Ellyn Satter, MS, RD, LCSW

It took me two years of reading, challenging my training and my biases to embrace the Health at Every Size (HAES®) Approach.

HAES® is not an excuse to “indulge” children or ignore accelerating weight, as some critics may claim. Feeding a child well and supporting healthful behaviors takes effort and planning. Ellyn Satter’s Trust Model and Health at Every Size® simply endorse and support health rather than weight as a goal, and a more stable and healthy weight often results.

When a client says, “Yes, but I don’t want her to struggle with her weight like I did.” I find it helps to ask, “If your child continues to be restricted, food-obsessed, and binging when she gets the chance, what do you see for her future relationship with food and her body?” After some discussion, we usually come to the same conclusion: that the child will struggle with her eating as an adult—and be heavier than nature intended her to be.

What are you worried about?

If you would like to join a new private facebook group for parents (moderated to be a safe space), send a “friend” request to Bon Appetites (little girl with pony tails) and you will be invited to join the group (and then she will promptly unfriend you). She’s not being mean, just protecting privacy.

Read Part 1: Healing a Child’s Food “Obsession”: Max’s Story

Read Part 2: Is My Child “Obsessed with Food?

Stay tuned for parts 4 and 5…

Parts of this post are excerpted and adapted from my book, Love Me, Feed Me

June 4, 2014

Is My Child ‘Obsessed’ With Food: Part 2

“I don’t even worry about her weight much, but her food obsession scares me to death. I struggled with an eating disorder, and I feel like the only thing she thinks about is when and how much she will eat.” – Alexis, mom to Greta age 2 1/2

Most parents of children who are preoccupied with food know there is a problem. Parents often rate their stress around food and their child as, “11 out of 10.”

The word parents use most often is food “obsession.” I prefer “food preoccupation” so as not to confuse the heightened interest, awareness and anxiety around food with the more clinical obsessive-compulsive behaviors. In addition, the word “obsession” has a more negative and blaming tone, while preoccupation invites empathy and understanding.

Your child’s interest in food is excessive if it takes time and attention from other activities, to the detriment of your child’s social or emotional development.

Max’s mom (from Part 1): We never play. He’s always pestering for food. If my husband is cooking, he’s right there, crying and pitching a fit. He even kicks and hits when he gets really mad if we don’t give him food.

Your child’s interest in food is excessive if dealing with it takes intense energy and effort on your part, is upsetting or causes conflict and frustration.

“…we’ve tried to control portions, push protein and veggies, tell him to eat slow, tell him about being healthy and eating healthy foods, to chew and enjoy food. We’ve seen a dietitian who recommended portion control and making him eat vegetables first, and talking about red-light and green-light foods, but that led to huge fits. He eats really fast— just inhales food then tries to get more. He’s always trying to get more.” (Part 1)

The following are signs that your child may be preoccupied with food:

He regularly eats rapidly, gobbles and stuffs food.

It takes effort to get her away from the meal or highchair: games, TV, and other distractions.

You bribe with a favored food to get him to leave a meal.

She is frantic, clingy during meal prep or around food.

At playgrounds/parties, he is more interested in eating than playing. He eats, whines, or cries to eat the whole time.

She exhibits high emotion around meals, whining and crying while waiting, negotiating and begging for food.

You feel like a “food cop,” not a parent, going to elaborate lengths such as these: Other children are fed at different times. You are not allowed to mention food or eat in front of her. You plan outings and vacations based on where you can best manage her eating.

The occasional pestering for sweets or for food while you are cooking is age appropriate. The difference is when your child’s interest in food gets in the way of being a kid.

If you have dealt with food preoccupation, or you’ve healed from your own excessive focus and interest in food, what have you learned? What has helped, what hasn’t?

If you would like to join a new private facebook group for parents (moderated to be a safe space), send a “friend” request to Bon Appetites (little girl with pony tails) and you will be invited to join.

Read Part 1: Healing a Child’s Food “Obsession”: Max’s Story

Stay tuned for parts 3, 4 and 5…

Parts of this post are excerpted and adapted from my book, Love Me, Feed Me

June 2, 2014

Another Veggie Study. Will it Change How You Feed?

Good reminder: often and early exposures help children learn to like veggies says an article about a recent study, which confirms earlier findings— most children learn to like foods with repeated exposures, and most parents give up after only a handful of tries. (Reminds me of my favorite “green bean study” which states that parents aren’t always good at knowing what foods a child “likes,” and to keep offering that food.)

Good reminder: often and early exposures help children learn to like veggies says an article about a recent study, which confirms earlier findings— most children learn to like foods with repeated exposures, and most parents give up after only a handful of tries. (Reminds me of my favorite “green bean study” which states that parents aren’t always good at knowing what foods a child “likes,” and to keep offering that food.)

This study (original here) seems to contradict earlier studies that suggested that a small amount of sugar, or flavors may improve acceptance of veggies and bitter tastes.

There was also little difference in the amounts eaten over time between those who were fed basic puree and those who ate the sweetened puree, which suggests that making vegetables sweeter does not make a significant difference to the amount children eat.

I have often seen flavor improve variety. I’m thinking of a nine-month old client who refused most veggies and “never seemed hungry,” who ate three roasted potato wedges when she was allowed to have the ones the parents were eating that were lightly seasoned with a sprinkle of salt, fresh herbs and garlic. (Mom emailed me ecstatic, wondering what to do with all her home-made purees of plain leeks and potatoes.) It’s complicated you see. Was it the spoon? The mom’s sense of relief and reassurance after our home visit? The new schedule that allowed for an appetite instead of the frequent feedings?

And then there is this:

Most children (40%) were “learners” who increased intake over time. Of the group, 21% consumed more than 75% of what was offered each time and they were called “plate-clearers”. Those who ate less than 10g even by the fifth helping were classified as “non-eaters”, amounting to 16% of the cohort, and the remainder were classified as “others” (23%) since their pattern of intake varied over time.

It may be helpful for parents to understand that children come with different approaches towards new foods…

The present investigation demonstrated that children respond differently to an intervention aimed at enhancing vegetable intake.

…and that appetites vary— often from birth. But, the labels rub me the wrong way. What does a label of “plate-clearer” vs. “non-eater” imply? Is it good or bad to be a plate-clearer? Is the implication that they eat more than they need or are at risk of ‘overeating’ and need more control? Will a parent of a “plate-clearer” worry and try to limit the child’s intake? Is the child a “plate-clearer” partly because they have already been restricted? Similarly, “non-eater?” How will that not worry a parent? Worry and poor support often combine and the parent may find himself in a counterproductive feeding cycle. My guess is that many ‘plate-clearers’ as well as ‘non-eaters’ are happy and healthy. (Would terms like “early acceptors” or “enthusiastic acceptors” or “cautious” be better? What terms might you use?)

Not really a “family” meal, and older kids eating purees? Limits and questions from the study.

Not sure how they controlled for feeding practices in three different countries. Was one provider more pressuring, or more familiar than another? (A parenting feeding survey was filled out, but only four of the variables were considered, and the parent wasn’t always doing the feeding.) The exposures occurred in private daycare centers or in the home in children recruited for the study, and the veggies seem to have been presented before the meal or snack in at least two of the countries. It seems that the adults were not also enjoying the purees as part of a communal meal… (don’t have time to read the original original studies that describe in detail.) It’s a relatively small number of children, and they only were in one of the groups, for example they were not offered plain artichoke initially and then offered artichoke with some sweetness. The study occurred over two months, I’m not clear what the time-frame was for the exposures, two weeks, ten consecutive days? We don’t have long-term data from this one study.

In addition, the older kids were fussier, which we know, but I don’t know many three year-olds who would eat artichoke puree. Heck, I’m not sure I would eat artichoke puree. But, they might like to peel the leaves off and eat the actual heart? My daughter enjoyed the communal eating of artichokes in preschool. We eat them rarely since good ones are hard to find in Minnesota, so it’s a treat and we dip the leaves in balsamic (husband grew up with butter so he does that) and then throw the leaves in a big bowl in the middle of the table. (But she probably would have been characterized as a “plate-clearer”— is that bad?)

My take-home message from this study and in general?

Yes, serve a variety of foods, including veggies early and often. But don’t panic if you don’t or didn’t. I’ve admitted before that with a move, a husband taking a bar exam and starting a job with crazy hours, and feeling in general overwhelmed and with little support, I didn’t provide a dizzying array of variety while my kiddo was learning to eat solids and she’s done fine so far. The attitude and atmosphere and feeding relationship are critical to raising a competent eater over time.

If you find the “evidence” confusing, you are not alone. One study says add sugar, another says don’t, and yet another found that offering a sweet taste after a bitter one seemed to increase acceptance… How to keep it all straight? Don’t worry, don’t sweat it, do your best. Eat together, enjoy it.

The best evidence to guide how you feed is your child. Responsive feeding, being tuned in to your child, her temperament and her reactions will guide you. If she’s rejected broccoli plain for weeks on end but gobbled it up when you served it from your stir-fry with honey and terriyaki, then go for the honey and terriyaki. Keep serving it plain if you like it that way too. If she happily tries one bite of everything and joyfully decides she loves Kohlrabi, great. If not, it’s the wrong approach.

Your child’s appetites can be supported and trusted whether she eats a lot or a little. If your child is happy, healthy, eating a fair variety and growing in a steady and healthy way, EVEN if it’s above the 90th% or below the 5th%, then that’s just how she is. Now erase “plate-clearer” and “non-eater” from your mind.

Don’t pressure your child to eat veggies, and don’t try to get her to eat them because it’s “healthy.”

Don’t panic if your “non-eater” isn’t loving artichokes by preschool. Some children take far longer to learn to like veggies, and the less you pressure, the better. I was eleven before I was offered my first artichoke, in my twenties before I had Thai food or sushi and enjoy them all.

What have you learned about your kids and eating? Has anything surprised you? What reaction do you have to the labels?

May 28, 2014

Healing a Child’s Food “Obsession” (Part 1): Max’s Story

This is not Max, but isn’t he cute? Now Max also enjoys treats as a part of a healthy relationship with food.

This is not Max, but isn’t he cute? Now Max also enjoys treats as a part of a healthy relationship with food.Helping Max Heal From Food ‘Obsession’

One of the most common issues I support parents around is the child who is preoccupied or “obsessed” with food. After a call with a client who has turned the corner, I was inspired to share their story. Max is on his way to becoming a competent eater. What this journal-style blog illustrates is the process, the doubt, the transformation, and that leap that parents make as they transition from trying to get a child to eat less to trusting the child to eat based on internal hunger and fullness cues.

Parts 2-5 of this series will begin to explore how to know if an interest in food is beyond typical, weight worries, why parents are told to restrict, why it backfires, and what I observe during the transition. At the end of each post following this one, there will be instructions to join a private Facebook group for parents struggling with this issue. While Max’s mom said, “No one understands,” she is far from alone. Most of my client calls are variations on common themes. A major reason for this series is that I have longed for a parent support group for my clients, a safe community of other parents who understand the challenges and can support one another. This series will introduce the issues, and with a group of volunteer moderators, we are ready to give it a try. But first, the hope and Max’s story:

Background

Max is 3 1/2 years old, the second child of a professional couple in San Francisco. He has a 5 year-old brother who is in the 10th percentile and not very interested in food. His parents are married. Max sleeps well and is highly intelligent and verbal. BMI is stable around the 85th% (overweight). His mother is slim, and his father has struggled with dieting and weight gain as an adult. The following are paraphrased highlights from client notes told in Mom’s voice, with permission. Details have been changed…

How it was: “His favorite teacher came to me with tears in her eyes. She said, “I love Max, but something is seriously wrong with him.” If food comes up in a story she is reading, Max spends the rest of the class talking and asking for food. He won’t stop. The teacher referred us to a child psychiatrist who said Max has OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder), but we found a different one who is just going to do play therapy and see what comes up.

Max never says he loves me. He doesn’t hug or cuddle like his brother did. We never play. He’s always pestering for food. If my husband is cooking, he’s right there, crying and pitching a fit. He even kicks and hits when he gets really mad if we don’t give him food.

My friend is a psych nurse. She says it’s probably a medical issue. Max has seen an endocrinologist and everything was normal. We are supposed to have him tested for Prader Willi syndrome next.

When he was a baby, he was 70-85% for weight, and the doctor said he was big, so I worried. He seemed to eat so much. I thought if I don’t limit how much he eats, he’ll get even bigger. I was limiting from when he was about 6 months old. I remember him crying after every meal and bottle. Since then we’ve tried to control portions, push protein and veggies, tell him to eat slow, tell him about being healthy and eating healthy foods, to chew and enjoy food. We’ve seen a dietitian who recommended portion control and making him eat vegetables first, and talking about red-light and green-light foods, but that led to huge fits. He eats really fast— just inhales food then tries to get more. He’s always trying to get more. No one understands what I’m going through.

I was a chubby kid until about third grade, then I thinned down. I’m slim naturally, but my husband is getting bigger and is always on a diet. I don’t want my son to struggle like my husband has. My husband doesn’t know when to stop eating, maybe it’s genetic? My husband was athletic and lean until he started working in an office and so many hours. He is stressed and doesn’t have time to exercise, he misses meals and overeats.

The family reached ‘rock bottom’ when the entire Labor Day holiday revolved around Max crying for more food. Mom found a few blogs about the Division of Responsibility and jumped in with structure and letting Max eat as much as he wanted. Mom contacted me for support.

Early November 2013, First Call: We started about eight weeks ago letting him eat as much as he wants at mealtimes. I can’t watch. It makes me crazy. He eats SOOO much. I’ve snapped a few times. I just cry after meals. I see that he is happier and more relaxed, but he’ll never stop eating. He eats until his tummy hurts. I don’t know if I can decide to let him be happy but obese or miserable and healthy. His doctor lectures us about diabetes and heart disease and mentioned food addiction. Maybe he’s just addicted to food?

He eats two full bagels with cream cheese, and they are big ones, I am full before I finish one, and he wants more food, pancakes, bananas… We can hardly get him away from the table.

Sometimes he sits and plays with his cereal after he’s eaten two bowls. Before, he would eat any food in front of him and never left any. Is this the beginning of him listening to his body?

He puts food on his plate and looks at me, almost like a challenge, just to get a rise out of me.

He screams within five minutes of snack being over. He screams for fruit and crackers. I know I’m not supposed to, but I give it to him. The first few weeks he would eat it and ask for more, but now half the time, he just carries it around.

Late November, Second call:

Max said “I love you” for the first time and he even climbed onto my lap. He stayed for about five minutes and let me tickle his back. Then his head snapped up and he said, “I’m hungry.” It was like he forgot for a few minutes and then remembered again. My heart just broke. I was so excited, but he can’t stop thinking about food.

The psychiatrist says she is seeing progress and we haven’t even told her what we are doing at home.

Mid December, Third Call: We hired a new babysitter, and we’ve told her a little of our struggles, but she hasn’t noticed anything! I was able to play Matchbox cars with Max for more than an hour while she cooked and helped my older son with his homework. This was the first time in Max’s life that we played like this. Ever. The first time someone was in the kitchen and he wasn’t right there.

I watched Max playing and having a blast at daycare. The phone rang, and it was amazing. He looked up, kind of blinked and said, “I’m hungry!”

My mother notices that Max is doing so much better at her house. She is totally supportive of our new approach. It’s still really hard to get Max to leave the table at home, but apparently there he hops down and plays. Why is Max doing this to me? He still pesters me for food and it makes me crazy. If I eat anything in front of him, he has to have it.

With my in-laws, he ate a huge meal and complained about his tummy hurting. I was so embarrassed. I don’t know how I can trust Max. I think he is gaining weight. It terrifies me. I know he’s happier but I worry about his health. I don’t think I can be okay with having a fat child. I feel stuck.

EMAIL: He’s eating huge meals, I can never trust him. He’s as happy as I’ve ever seen him but I can’t stop crying.

Strangers will comment about how thin his brother is, and how “big and strong” Max is. I know people pay attention to how much he eats, and he does have that little tummy. There is just so much talk about my kids and their bodies.

If I try to suggest dinner is over, he puts up a fit. I’m so embarrassed. I know my in-laws are judging me and Max.

January 2014, Fourth Call: Things are so much better at home. He never carries fruit around anymore. I have to really think about it or I forget how much progress we have made.

I wonder if my anxiety sets him off so he eats more, or if him eating more sets off my anxiety. I can’t tell which comes first. He still sometimes eats really big meals. Will he ever be ‘normal?’

We went to the grocery store and he saw the candy and immediately asked for it. I said, “Sure, choose a candy” and he picked M & Ms. Normally I would have told him he could have maybe five, and I know he would have pestered me the whole way home for more. He asked how many he could have and I said he could eat as many as he wanted. I honestly felt so relaxed, I didn’t care if he ate the whole bag. Then he ate about four or five and said he’d save the rest. I wanted to let him know he could eat them all and we could always buy more another time, but he just kept them in his hand and put them in the pantry when we got home. It blew my mind. I’m happy now that he is actually pestering me for those more ‘normal’ foods like candy or ice cream and not begging for more pasta or chicken.

He asked for seconds on noodles, and I gave it to him and I was cutting his meat and then he just said, “I’m done.” Pasta was the one food I thought he would never turn down, he always begged for more of it. I almost cried tears of joy.

Late January, Sixth Call: I used to think he wasn’t affectionate. But he is. Max now climbs onto my lap, says, “I love you” all the time. Our psychiatrist says he’s doing great. No need to see us anymore.

I know now not to discuss eating at all, or tummies, or nutrition. The less we talk, the more relaxed I feel and the better he does.

We were all fighting nonstop before this. My husband and I were always fighting over Max’s eating. It’s so much better now I can’t believe it. My husband has noticed how much calmer I am too and more relaxed, but it’s still not easy. I try not to talk to him about it. He’s so sick of it. I think my husband is being better about not missing meals too.

I look forward to talking to you all week. No one understands this. I know this is the right approach now. My biggest challenge will be my in-laws. They are both slim and very focused on healthy eating and exercise. They think that being thin is the only way to be, and that being fat is a moral weakness. They talk about how much Max eats and his tummy all the time.

His teacher pulled me aside and said he is like every other kid now. He can share snacks, he plays, she thinks he is learning better too.

Getting him down from the table after dinner isn’t a problem anymore. Sometimes we share an apple after dinner and he just says, “I’m full.” And gets down. It feels like a miracle. I feel so grateful we did this, and I’m finally trusting that Max can learn to eat well and have a healthy body and be happy.

Stay tuned for part 2: Is Your Child ‘Obsessed’ with Food?

May 8, 2014

Spaetzle cooking fun and new food tips

photo from jamesbeard.org and recipe for dill spaetzle

photo from jamesbeard.org and recipe for dill spaetzleLast night red cabbage and maple-dijon glazed pork were on my meal plan, but what to cook with it? I’d made potatoes already twice this week, and didn’t want noodles… Spaetzle! I’d had home made only once about 20 years ago, thought it looked complex, heck there are even special gadgets to make them! I looked up the recipe in Joy of Cooking, glanced at a few online resources and thought it looked like fun.

If you want to get messy, do what I did… I made the dough then tried smooshing it into the boiling water with the back of a spoon through a colander as instructed, which was hard work and ineffective. With my daughter’s help we tried the back of a bowl, like a press, and then her hands (messy!, sticky!, and careful with the steam and boiling water!). We cooked in batches though honestly we didn’t even finish 1/3 of the batter as it was sticking to us, bowls, colanders… They cook in about 15-30 seconds!My daughter scooped out finished ones and put them in a sieve and then in a bowl. Then reheated for 30 seconds in the microwave. It was lots of fun and the spaetzle were tasty! We didn’t fry them in butter, but maybe next time. I liked the bite to them, in contrast to noodles.

I’m wishing I had taken pictures, but my hands were so messy and sticky I simply couldn’t! Spaetzle gadget is on my wish list for sure. Whole family enjoyed them.

Tips:

When trying something new, have a few options that are accepted or favorites. My daughter likes the pork chops and red cabbage, so I knew she wouldn’t go hungry if the Spaetzle was a flop. Same for me actually! Can also plan on a more filling dessert.

Serve new foods with a familiar sauce to make that flavor bridge. Put a ketchup bottle out if that’s the preferred condiment.

I omitted the nutmeg and kept things simple: eggs, flour, salt, baking powder and milk.

Give kids a context. “These are made with the same things as the noodles you like.” Or, “This is how Germans made noodles, aren’t they fun looking?”

Children are more likely to try something they helped cooked, but no guarantee! Remember not to pressure them to eat.

Cooking new foods is fun, messy, and a learning experience! What new things have you tried recently and how did it go??

March 18, 2014

Parents on dessert with dinner

I asked my facebook readers and a few past clients to share their experiences with serving dessert with the meal. For many workshop attendees or new clients, this is the idea they struggle most to accept: “How will I get them to eat anything if I can’t bribe with dessert?” or, “I can’t accept that he gets rewarded with something he likes if he hasn’t eaten anything healthy first.”

After serving family-style, serving a child-sized portion of dessert at the same time as other foods is the second most helpful tip, according to my clients. I also find that for families who do this from the start, they are much more likely to have children who are able to enjoy all kinds of foods and grow in healthy ways.

Note: dessert can include fruit, cookies, ice-cream, popsicles, apple-sauce, yogurt, home-made or store-bought… You don’t have to have dessert every day or even most days. You don’t need to eat dessert if you don’t want to. I personally would rather enjoy more turkey curry with rice than eat ice-cream, but we include a dessert most nights for our daughter.

Families find lots of ways that works for them. If what you are doing works for you and your child, keep up the good work. If however you are tired of negotiating, your child is anxious at the table, not enjoying a great variety, preoccupied with sweets, or having trouble eating the right amounts for healthy growth, consider serving dessert with dinner.

I will admit to a selfish motive for this post. Often, a skeptical client needs to hear that it works from other formerly skeptical parents. I plan to link to this post in my consult summaries for years to come! Thanks to all the parents who shared. Please feel free to leave your comments/experience below as well.

Musings on serving dessert with the meal

My 18 month old usually seizes on her dessert first and eats some of it, but then switches back and forth among different foods for the rest of the meal and often leaves some dessert. My feeling is she’s probably going to eat some dessert whether she’s hungry or not (at least if she’s like me) so may as well let her weave it in with her hunger rather than stuff it in after finishing some prescribed portion of “healthy food.”

*

Mine are 2 (not picky) and 4 (picky). Dessert with dinner works quite well at my house. The kids still sometimes ask for more of dessert, but they don’t persist for long. And it doesn’t seem to affect their overall intake. When they are hungry and the food is familiar and stuff they would eat normally, they eat anyway. If they are not hungry or the food is too challenging then they may not eat much of it after their dessert–but it would have been that way anyway. Occasionally my 4 year old will take bites of dessert, bites of dinner, bites of dessert. Sometimes I suspect starting with dessert actually stimulates my 4 year-old’s appetite or at least lowers her resistance to the meal as a whole.

*

I couldn’t believe how well this worked. She would lick her homemade smoothie pop, then eat some beans, then lick the pop and go back and forth. Half the time, dessert melts now while she eats dinner!

*

My daughter was obsessed with fruit. We don’t really do cookies and such, but she would whine and cry for fruit at meals. She would eat so much that she wouldn’t eat anything else. Katja suggested we try to serve fruit like dessert at mealtimes, a reasonable portion with the meal, and after three days, she was more calm at the table, and more interested in the other foods. She ate more of the other foods, veggies, beans etc. We are vegetarians too, and to see her not so anxious and whining for fruit and enjoying meals and eating more balanced was amazing. If someday she gets as interested in cookies and the sugary stuff, I think we’ll start serving it so she doesn’t get so obsessed.

*

This works great at our house. My children are 4 and 6. It helps us avoid the “dessert” concept and in fact, we don’t refer to it as dessert at all. A sweet something (cookie, a few M&Ms, licorice, fruit, etc.) is just offered on the plate with the rest of the meal, a few times weekly. For us, it has helped keep all foods on the same playing field, avoids bartering and gives more eating autonomy to my children; they are offered a variety of foods and can choose how much to eat and at what point in the mealtime. They eat slower, and there’s no pressure or after-dinner expectations. When they’re done, they’re done.

It helps reduce anxiety. Food is food. Serving dessert with meals levels the playing field and opens up curiosity and space for other foods, rather than just fixating on if and when dessert is coming…

Back when we bought into dessert was a reward for eating dinner, both my kids were sweet tooth junkies. Now that dessert is just part of the meal, it’s impressive to see how well they self regulate the sweets, and choose foods they appear to need over eating a lot of something because it’s available for a limited time. With one typical and one selective eater, a little treat before dinner helps take the edge off whatever is distracting them from eating, often leaving most the dessert and choosing more of the meal.

*

This is also the thing that helps my clients the most. It ends the daily struggles of “did I eat enough?” and really keeps everyone on their side of the DOR*.

*

I notice that serving dessert with dinner lessens the kids’ anxiety about WHEN dessert will happen and if they’ll get enough. It also normalizes the whole idea that dessert is food and not an event.

*

The dinner table was a pretty scary, anxiety-ridden destination for my son. We started DOR about 6 months ago when my son turned 3 years old. Every dinner is now family style on pretty platters and often lit by candle light (huge positive change) and some sort of treat is included. It made the table approachable again. Screams of “no no no!” have changed to “I’m ready, Mmm, looks good”. Sometimes he grabs a treat first, but many times it’s only a few bites and he’s grabbing real food that he didn’t touch in the past. He still doesn’t eat huge portions, but removing the fear of food is such positive progress. (*SE is selective eater which is beyong typical picky eating and involves anxiety, and often a history of a feeding challenge like oral motor problems, reflux etc.)

*

Prior to the DOR, I… Like so many used dessert as a bribe. Only he resisted most desserts anyways and that tactic failed. The first few weeks of the DOR were very difficult and our dinners were 100% safe…oreos, chips and bananas for dinner? Sure! After weeks of DOR and anxiety visibly lessened, we faded out 100% safe, to 50% safe to 1-2 safe with dinners. Safe includes desserts, fruits, snacks. Whatever he likes. The most amazing part of this is losing what I like to call the OMG factor. Typically, kids will pile cookies on their plates and eat like its a “forbidden” food. My SE takes 2 oreos, eats a carrot, takes a bite of rice, finishes a cookie. All food is equal! This is the healthiest relationship with food I’ve ever seen! It seems to calm him down, give him comfort that he HAS something to eat and enjoy while exploring the other options!

*

My kids fixate on dessert if told it is coming after dinner and will be “done” earlier to facilitate getting the sweet stuff sooner. When we have served dessert with dinner (2 gummy worms, fruit, one piece of chocolate or one cookie), they go back and forth, but eat more of the ‘real food’ than if focused on getting a dessert. It also takes away bargaining. . . I love that part.

*

After the novelty of dessert with dinner wore off, we found that our kids sometimes go for dessert first but not always. Our younger child (who has been raised with DOR since birth) typically alternates between the entree and the dessert and often doesn’t bother finishing the dessert.

*

We don’t do dessert with every meal… depends on what we have around, what else we’ve eaten that day etc. My kids know that dessert happens when it is gonna happen and that it is almost random.

*

When we have dessert (cookies or ice cream typically), I give it to her with dinner. Sometimes she finishes it and sometimes she doesn’t. Initially she would try to eat all of it even when full, until I reassured her we could save it for later (with a snack or meal over the next day or so). This took the internal pressure off of her to finish in case she might not get to have all of hers. Now, I can say “should we save it or are you done with it?” If she says she’s done, I can toss it. At 9 years of age, she now has the language and thinking and trust to be able to communicate this without my cues. Since my eating has been a struggle, it’s reassuring that I can use DOR with her so she will not have the same struggles I have. Sometimes she asks for ice cream or cookies, etc. I will often honor this request in the next day or two and tell her that we can at an upcoming meal or snack. Typically we have dessert 1-2 times a week.

*

We don’t have dessert every night, but it is fairly common (especially following this year’s – our first – trick or treating at Halloween). We have always followed DoR with our now 3.5 year old, and find that when sweets are offered as part of the meal she’s just as likely to eat only part of the sweet as she is to eat all of it. Another poster mentioned how their children seem to eat better overall when a sweet is included with the meal, and we sometimes see the same. I think our daughter can get too hungry and feel a little overwhelmed by the time dinner rolls around, and having that very palatable item included in the meal just gets things started for her – sort of like priming the pump.

On the idea that if you never serve sweets, they won’t want them:

OH how I wish it were that simple. I am a wholefoods/health food devotee, have been for 25 years. I made all my own baby food from scratch, never brought processed food or sweets into the house, and only ever offered up “real” foods to my daughter. If/when she was ever offered a treat (which was limited to special occasions like birthdays) it was made by me from scratch using whole grains, no refined sweeteners, etc. I truly believed that if I never exposed my child to anything but whole, real foods that she would never develop a taste for sweets and would always make “healthy” choices. BOY was I wrong. Around age 3 my daughter became hyper aware of all the treats that other kids were being offered and began to ask questions about why other kids got to eat sweets and she didn’t. I still held my ground about no sweets in the home, but loosened my grip when at parties, etc. Her interest in sweets continued to grow and she felt confused and sad about why I never offered ice cream or cookies at our house. And then the lying and hiding started–when she had a treat at school or a friend’s she would lie and say everyone else had some, but not her, or she would stash treats in her pockets and secretly eat them behind closed doors when she returned home. She was feeling ashamed and scared and because I so value my relationship with my daughter, I knew things had to change and so I have slowly loosened the reigns around sweets and other “junk” food. For some kids, out of sight out of mind may work, but not for my child.

And from one busy commenter: It works!! Just that simple.

*DOR is the Division of Responsibility. Parent decides what, when, where and child decided how much to eat from what is provided. Always includes something the child can eat. A big part of Satter’s trust model of feeding is to serve dessert with the meal as well as regular sit down family meals and planned snacks.

For more on serving dessert with meals, sweets and treats strategies and getting back on track with your child’s eating, check out my book, Love Me, Feed Me on Amazon.com

February 10, 2014

Constipation and Picky Eating

“I have been trying to get her to drink more to deal with her constipation, but I feel like it’s making her drink less and she resents it.”

This issue keeps coming up for clients, so I thought I would post this excerpt from my book, Love Me Feed Me, with some minor changes and additional thoughts… (Excerpt in italics.)

Sometimes a painful diaper rash or other issue can set up the cycle of withholding stool that the child can simply “out-clench,” in spite of a diet full of fruits and fiber. Other times, low fiber or fluid intake can contribute. In addition, some children with food intolerances may experience constipation.

For some reason, more often than not I see constipation and later toilet training in children who are also selective eaters where there are significant feeding battles. I don’t understand the connection, but I have theories: A medical issue, pain from constipation is decreasing the child’s appetite, or the child is very intent on doing things on his or her own time frame…

If your child is chronically constipated, she is probably not very comfortable. It can also lead to decreased appetite and, at times, intense abdominal cramping and even vomiting—not to mention pain with BMs and, rarely, anal fissures, which are very painful and make matters worse . A fissure is like a paper cut on the sensitive anal tissue, and it hurts as badly as it sounds. Some children can have a BM most days and still have significant constipation. If your child has unexplained abdominal pain, soiling of the underpants (encopresis, which happens when stool leaks around a firm ball of stool), or a distended abdomen, then impaction and constipation need to be ruled out. A simple X-ray can be diagnostic if the history is not clear-cut. Very rarely, there are anatomical reasons for chronic constipation, but most often it is a “functional” problem that can be corrected without surgery…

Once a child is significantly constipated for weeks or months, the colon stretches, and this becomes a “chronic” condition. The colon is made of smooth muscle, and like any other muscle, it can get out of shape. There is no quick fix. It takes up to six months for a dilated colon to heal and get back into “shape” and proper function. Many families will try medication for a few days or even a week, thinking things are better and stopping treatment only to have the problem resume almost immediately. Parents often get angry with the child and think they are being naughty. Truth is, if a child has had significant constipation or pain, the body’s natural reflex is to hold the BM in. Over time, it can be hard for them to understand and pick up on what their bodies are telling them. As parents stand over the sweating, purple-faced withholder shouting, “Let it out of your body, you will feel better!” the child simply can’t comply.

In general, I recommend optimizing intake of liquids, fruits, and vegetables. However, chances are if you are reading this, this is already a challenge! So, when that fails in the short term, MiraLAX laxative, which is flavorless and disappears when stirred into liquids, is an amazing tool to use while you work on feeding. The goal is to help your child have a daily, soft, pain-free BM for months. And by soft, I mean the consistency of toothpaste. Sorry for that image, but it helps define “soft.” If you find a fiber product, or something else that works for your child, you and your doctor can go with that. My main point is that it takes lots and lots of time. You basically need to overpower the child’s ability to hold in the BM. Keep up the beginning dose, and decrease the dose over a period of time as long as symptoms don’t return.

Stay home when you start this process and expect soiling and accidents initially, but every few months wean the dose down and see what happens. Your child might be on Mira-LAX for 18 months or more, but hopefully by then she will have learned to respond to her body’s cues. Oh, and don’t forget to relax yourself, don’t pressure, stay emotionally neutral, and don’t stop too soon.

A little more about functional constipation. Kids can forget how to have a BM properly. Even if they want to, pain leads to the reflex clenching or constriction of the sphincter. Kids lose the ability to understand the input, and know which muscles to relax to allow the BM to pass. This is also called “pelvic floor dysfunction” and can happen in adults as well. Physical therapy in can help. I have not worked with children who did PT, but it is an option to look into PT in children . (Be wary of behavioral approaches some sites offer to address diet, that almost always means pressured feeding.)

Making Them Eat More Fruits and Veggies Almost Never Helps

Children with constipation and feeding battles are vulnerable to more pressure with feeding. Well-meaning doctors and dietitians think that pressuring and forcing a child to drink more or eat more fruits of vegetables will do the trick. This approach is problematic for two major reasons.

With established constipation, increased fruit/veggies or water intake most likely won’t resolve the issues on it’s own.

Pressure is still pressure and it is still most likely to backfire and make children eat less well or drink less. Your child’s reaction will let you know. If he is amenable to attempts to increase his intake of liquids, fruit and fiber, fine. If he resists, it won’t help and may worsen eating problems and constipation.

A few ideas: Start with a soluble fiber supplement like citrucel. If it results in soft daily stools, continue to feed well with the DOR and support. If it doesn’t do the trick, move up to Miralax. Start with the recommended dose and titrate until daily soft stool (ask your doctor for help). Stay with the same dose for 6-8 weeks then try to decrease by 1/2 teaspoons every 8 weeks or so. If the BM gets hard again, go back up to the last dose.

While your child is on the Miralax, optimize feeding well with the Division of Responsibility (DOR). Boost liquid intake by serving liquids in fancy cups, from straws, have a “bubbler” at home so she can help herself. Have tea parties, and try not to pressure. Serve favored fruits and veggies often. Watermelon is mostly liquid for example. Look for those juicy fruits. Consider serving dried fruits or freeze-dried fruits. Look for recipes together than include fruits and veggies. Try to switch to whole grain alternatives of accepted foods like waffles or crackers. Have her help you prepare foods if she likes it. She’s more likely to try it, but it’s no guarantee. (Cucumber salad is a great one for example, and simple.) Serve fruits and veggies with favorite sauces and dips. With her knowledge, think about adding frozen fruits and veggies to smoothies, or add flax seed oil. Consider a multivitamin with Omega oils or a fish oil chewy. Consider a probiotic food source or supplement if she accepts them. (Yogurt, yogurt drinks or capsules.) There is some evidence that these products can promote gut health, and if they are accepted it doesn’t hurt.

I hope this is a helpful start to a tough topic. What have your experiences been?

* Miralax and other laxatives appear safe to use for the longer time-frames it takes to deal with chronic constipation. Talk with your doctor if you have questions.

February 6, 2014

Negative Emotions and Appetite

Our kitchen table is as much a stress-free zone as we can make it. If something tough comes up during mealtimes, we ‘put a pin in it’ and talk after dinner. Recently, it hit me how profoundly negative emotions can kill appetite, when something came up during the meal that was emotionally charged for our daughter.

Watching her reaction took me right back to my own childhood. It didn’t happen often, but if something came up that I was embarrassed about or when I felt guilty (I was exquisitely sensitive to guilt and shame) during a meal, I remember that my appetite instantly disappeared— and I had a big appetite. My eyes would brim with tears, my mouth fill with saliva, my face would flush and heat would engulf me, all in a matter of seconds. If I happened to have food in my mouth, I remember wanting to spit it out and swallowing with great difficulty. Even if it was something I was enjoying, the meal….was…over. I had not thought of that for so long until I saw a similar response in my 8 yo competent eater who pushed her plate away saying, “I don’t want to eat anymore.”

On that occasion, we took a few minutes to process, calm down and promise to talk later. After a few minutes pause, the meal went on and she ate a few more bites. For children who are anxious about food, or have challenges that may already make their appetite cues less easy to read, trying to preserve the table as a pleasant oasis will help support intake and picky eating. Think of it this way, with everything else going on in stressed out bodies— knots in their tummies, flushed skin, increased heart rate (stress response) it’s impossible to hear other cues. Whether they need fuel or not, they simply can’t feel hunger.

Start now, declare your table a stress- and conflict-free zone.

Acknowledge tough feelings and promise to talk about it after the meal or if you have to, leave the table for those hard conversations.

What do you think? Do you remember feeling this way? Do you see your children react to stress with a decreased appetite? Have you seen your child’s appetite bounce back after removing meal-time stressors or battles?

January 31, 2014

Survey Says? Chicken Suqaar is Favorite School Lunch

I had lunch the other day with my second grader. I watched as tiny Kindergartners (I swear they look smaller every year) hung on to precariously balanced trays with pineapple juice slopping everywhere as they happily served themselves carrots and celery from the veggie bar.

This is not a lengthy erudite discussion about school lunches, weight worries etc., but just my challenge to the assertion that kids* can’t or won’t eat “grown up foods” or anything other than fries and pizza. They can and do.

I surveyed the 5 children with whom I could converse amidst the low roar of a room full of grade schoolers. “What are your three favorite lunches at school?”

There were pizzas and burgers, and Italian dunkers in the list, but the only one all 5 kids listed was chicken suqaar, a traditional Somali dish.

I feel lucky that our school district has some pretty great, tasty, and balanced meals, even if overall we agreed that the sweet potato fries could use a little salt… But I digress.

Here are a few reasons why I think these kids were enthusiastic about a “challenging” food:

There are no adults coercing, encouraging, or shaming them into choosing one food over another. It was their idea.

It is served with a familiar food: rice.

It tastes good.

The school menu has had high expectations for kids since their first day of Kindergarten with a varied menu.

The foods like Chicken Sugaar show up fairly regularly (about twice a month), with an alternate wrap sandwich if they aren’t ready to try something new yet. (I watched this work when M saw a new menu item and she decided to check it out the first time by watching others eat it with her home-packed lunch that day, but tried it the second time around.)

The cafeteria has lovely posters with bright colored foods with descriptions like “crunchy” and “sweet.’ There are no posters (this time) or obvious messaging about what they have to or should eat.

For another district doing amazing things for the kids, check out ITS Meals at Provo. I get hungry looking at their posts and want to know how to get such a talented food artist at every school!

*I do a lot of work with and advocacy for families with children who have food aversions and are selective eaters. I am referring to the general population here, knowing full well that some children will struggle, but the idea that kids in general can’t enjoy a variety of foods is what I am getting at with this post.

January 14, 2014

Scaring Parents to Motivate Healthy Feeding? (With a Note About Accurate Measurements)

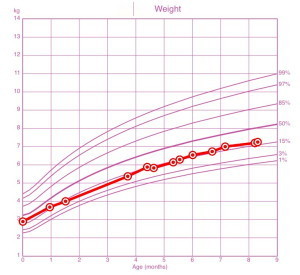

Does this look like the chart of a child who is “failing to thrive?”

Worry, worry, worry! All good parents are doing it!

“She’ll need a feeding tube if you can’t get her to eat more.”

“She has pre-prediabetes…”

The parents I talk to, and emails I read are increasingly suffused with fear and anxiety. A very few cases are true emergencies, with children dropping weight or refusing anything by mouth, but many terrified and tearful parents are facing relatively minor feeding issues and some are even within the range of normal.

I don’t mean to belittle the fear. There should always be an investigation to see if the fear is warranted, but I hope to address with this post my belief that parents are being manipulated and bullied with fear tactics that are at times unwarranted and are almost always unhelpful.

Look at the growth chart above. This is from an infant who was misdiagnosed with “failure to thrive” and a “feeding disorder” and the parents were simply sent away with the vague threat of “Get her to eat more or she’ll need a feeding tube.” (The clinical snapshot? A child with a recent infection and antibiotics with decreased appetite and intake, a mom already anxious, now terrified that her daughter is in grave danger. The trigger was a misplotted weight measurement, but the seeds of fear had been planted and fertilized…)

With that threat of a feeding tube and no support, I’ve had parents admit to screaming at children to eat, force-feeding them while pinned to the floor, sobbing, begging, bribing, holding an infant’s head and forcing in the nipple… Before listening to parents with feeding problems for the last several years, I would have judged. Now I save my judgement for the system and the clinicians who so poorly serve parents and children.

I hear from parents of larger-than-average kids told their child has “pre-prediabetes” and told the child will die young if they don’t get them to lose weight. Many of these dire warnings are based on arbitrary BMI cutoffs alone with no clinical or historical risk factors, and “pre pre diabetes” is not a thing.

Scared parents without proper support and information can easily fall into counterproductive feeding practices and unwittingly make matters worse. Alas, I believe instilling fear is the intention, that somehow if parents are scared enough, they will magically get 100 more calories in a day or get the child to stop sneaking sweets at friends’ houses.

Trying to make a child eat more or less, overriding the cues of a screaming or anxious or withdrawing child feels awful and doesn’t help. Feeding from a place of confidence and feeling supported, even in the face of real challenges and uncertainties, gives parents and children the best hope.

Have experts tried to scare you? When were you scared but felt supported? If you feel like a doctor or nurse or feeding expert is using threats and fear-mongering to try to motivate you to achieve calorie or weight goals, is it working?

And PLEASE if there is ever a weight or height measurement that is concerning, insist on a recheck, and PLEASE plot it yourself. I cannot tell you how many growth charts I see with errors.