Stephen Lycett's Blog, page 4

August 29, 2018

Lost Houses

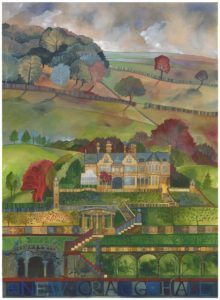

Whilst I was nearing the end of Mr Blackwood’s Fabulorium in early 2016, I had to take time out to write the text for Lost Houses of the South Pennines, the booklet (later a book) which accompanied my artist daughter Kate’s exhibition at Bankfield Museum in Halifax. The houses in question – there were ten of them – have disappeared, in some cases without trace, or been reduced to a few scattered stones. Had I started the project earlier, some of the stories might have found their way into Mr Blackwood.

Take, for example, the story of New Cragg Vale (picture below). Of Hinchliffe Hinchliffe’s mills near Mytholmroyd, the local rector wrote: ‘If there is one place in England that needs legislative interference it is this place; for they work 15 and 16 hours a day frequently, and sometimes all night. Oh! it is a murderous system and the mill owners are the pest and disgrace of society…!’ Workers were fined for unpunctuality, children beaten for minor misdemeanours. Small wonder, then, that the most hated name in Cragg Vale was that of Hinchliffe Hinchliffe. He died as a recluse in Southport and was survived by only one of his five children, Helen. Although she was said to have been spoiled by her father, she grew up to be very different in outlook. She was married three times. Her third husband was a 22 year old bank clerk from Harrogate named William Algernon Simpson. Helen Hinchliffe was then 48. William Algernon Simpson (or Algy Simpson-Hinchliffe, as he chose to be known) initiated a new social era in Cragg Vale. Between 1904 and 1906 he extended and re-modelled Hinchliffe Hinchliffe’s house at Cragg Vale. He and his wife spent lavishly – and not just on themselves. Newspapers of the time reported eagerly on tea parties, picnics for the workers and social events for schools and clubs: ‘Christmastide was again celebrated with no unstinted hand by Mr and Mrs Simpson-Hinchliffe. A beautiful tea was in the school for the children, after which they were invited into the upper room, and as they entered it their breath was almost taken away with the glorious sight which met their view. Standing in the middle of the room was a huge Christmas tree, from which were suspended toys of almost every imaginable character. These were given to the children along with a tin of Harrogate toffee and an orange.’ A further report tells how Algy, dressed at Father Christmas, accidentally set his beard alight and badly burned his face. How unlike the days of Hinchliffe Hinchliffe, who is said to have charged guests for the cigars he offered them! Unlike almost all the other houses in the exhibition, New Cragg Hall did not endure a lingering death by neglect and decay. In the early hours of August 11th 1921 it caught fire and within a few short hours it was nothing but a blackened ruin, its roofless gables outlined starkly against the sky.

Or take the story of Castle Carr (picture top), built between 1859 and 1867 near Luddenden Foot by Joseph Priestly Edwards, Deputy Lieutenant of the West Riding and Captain in the West Yorkshire Yeoman Cavalry. It was intended as a country residence and shooting lodge. No expense was spared and no taste shown. Everything was conceived on a vast scale. Visitors entered through a Norman arch, which contained a portcullis and to which a keeper’s lodge (with clock tower) was attached. Having alighted from their carriages, they climbed a handsome flight of stone steps, which were flanked at the top by two life-size crusaders, and then through a carved stone screen into an Ante Hall, to be greeted by yet more stone crusaders. To the right of the Ante Hall was the Great Banqueting Room, whose walls were covered with carved panels and whose focal point was a massive stone fireplace with marble pillars, carved capitals, tessellated hearth and moulded stone fender. Opening out from the opposite side of the Ante Hall was the Picture Gallery, which contained a similar wealth of decoration and which led in turn to the Grand Staircase with its elaborately carved balustrades, each newel post being capped with a carved Talbot hound. At the head of the staircase was the Gallery, which allowed access to the Sitting Room, the Billiard Room and the Library, all of which had their share of Talbot hounds and carved hunting scenes. Captain Edwards did not, alas, live long enough to enjoy the baronial splendours he had created in the Luddenden Valley. He and his eldest son, Priestley August, were killed in the Abergele railway disaster of 1868, as they were returning from a weekend shooting party. So badly disfigured was he that his body could only be identified by his keys.

The story of many of the houses is the story of the rise and fall of the mill-owning families who built them. For anyone interested in following the two stories above in more detail, as well as the stories of all the other houses, go to my daughter’s website: www.katelycett.co.uk

August 12, 2018

The Thames in 1851 – an elongated cesspool!

As a thoroughfare, the Victorian Thames was much busier than the modern one. Engravings from the mid-century show the river so packed with steamers that it is remarkable that they did not collide more often. Steamers were designated above or below bridge depending on whether they operated upstream or downstream of London Bridge. The above-bridge boats, all of them paddle steamers, belonged either to the Citizen Steamboat Co, the Iron Boat Co or the Westminster Steamboat Co. All the vessels belonging to the Iron Boat Co, on whose P[addle] S[teamer] Haberdasher Blackwood’s party travels, were named after City companies. (There were even a PS Fishmonger and a PS Spectacle Maker!) The fare from the Old Swan Pier at London Bridge to Lambeth or Vauxhall was a penny, a tariff which gave the boats their nickname of ‘penny steamers.’ Most below-bridge steamers, which operated as far afield as Gravesend and Ramsgate, belonged to the Diamond Funnel Company. I have not invented the semaphore communication system between the bridge and the engine room (see Chapter V); incredible as it may seem, that really was how the boats were directed. There was no bell or telegraph connecting the Master to the Engineer; instead a lad of thirteen or fourteen stood on the engine room hatch and translated the Skipper’s hand signals into shouted commands such as ‘Full ahead!’ or ‘Half astern!’

The Thames was not simply a thoroughfare; it was also an elongated cesspool. Although the ‘Great Stink’, which finally prompted the government to take action, did not occur until the summer of 1858, there had been plenty of lesser stinks before that, Parliament having enacted in the 1840s that all domestic cesspits should drain into the sewers and thus into the Thames. For many of the visitors who flocked to the Great Exhibition, the unexpected horrors of the river must have been as striking as the eagerly anticipated wonders of the Crystal Palace.

The Thames in 1851

As a thoroughfare, the Victorian Thames was much busier than the modern one. Engravings from the mid-century show the river so packed with steamers that it is remarkable that they did not collide more often. Steamers were designated above or below bridge depending on whether they operated upstream or downstream of London Bridge. The above-bridge boats, all of them paddle steamers, belonged either to the Citizen Steamboat Co, the Iron Boat Co or the Westminster Steamboat Co. All the vessels belonging to the Iron Boat Co, on whose P[addle] S[teamer] Haberdasher Blackwood’s party travels, were named after City companies. (There were even a PS Fishmonger and a PS Spectacle Maker!) The fare from the Old Swan Pier at London Bridge to Lambeth or Vauxhall was a penny, a tariff which gave the boats their nickname of ‘penny steamers.’ Most below-bridge steamers, which operated as far afield as Gravesend and Ramsgate, belonged to the Diamond Funnel Company. I have not invented the semaphore communication system between the bridge and the engine room (see Chapter V); incredible as it may seem, that really was how the boats were directed. There was no bell or telegraph connecting the Master to the Engineer; instead a lad of thirteen or fourteen stood on the engine room hatch and translated the Skipper’s hand signals into shouted commands such as ‘Full ahead!’ or ‘Half astern!’

The Thames was not simply a thoroughfare; it was also an elongated cesspool. Although the ‘Great Stink’, which finally prompted the government to take action, did not occur until the summer of 1858, there had been plenty of lesser stinks before that, Parliament having enacted in the 1840s that all domestic cesspits should drain into the sewers and thus into the Thames. For many of the visitors who flocked to the Great Exhibition, the unexpected horrors of the river must have been as striking as the eagerly anticipated wonders of the Crystal Palace.

July 21, 2018

Why 8 October 1851?

Mr Blackwood and his party visit the Great Exhibition on 8 October. I chose the date for two reasons: one is that it was the day of peak attendance, when 109,915 people went through the turnstiles; the second is that it was the day that the Duke of Wellington paid his last visit to the Crystal Palace. (Tennyson and Lord Palmerston certainly visited the Exhibition, though it’s most unlikely that they visited on the same day as the Duke or even as each other. In general I tried to avoid poetic licence, though on this occasion I succumbed.)

The Duke, who was still regarded as a national hero, was cheered loudly by his admirers. Unfortunately, visitors at the other end of the building, hearing the noise and not knowing the reason for it, panicked and fled for the exits, having supposed the building to be on the point of collapse. The duke’s confrontation with Corporal Costello is, of course, entirely imaginary.

Although there were no weather forecasts in those days, there were weather reports for the previous day. I was thus able to find out from the shipping columns of The Times what the weather was like in London on the three days of the excursion – in other words: fine, fine and wet. The excursionists were fortunate to have two fine days: the summer of 1851 was one of the wettest of the century.

The image at the head of this post is the only surviving photograph (actually, a daguerreotype) of the Duke of Wellington, taken in 1844, eight years before his death and seven before his visit to the Crystal Palace.

8 October 1851

Mr Blackwood and his party visit the Great Exhibition on 8 October. I chose the date for two reasons: one is that it was the day of peak attendance, when 109,915 people when through the turnstiles; the second is that the Duke of Wellington paid his last visit to the Crystal Palace. (Tennyson and Lord Palmerston certainly visited the Exhibition, though it’s most unlikely that they visited on the same day as the Duke or even as each other. In general I tried to avoid poetic licence, though on this occasion I succumbed.) The Duke, who was still regarded as a national hero, was cheered loudly by his admirers. Unfortunately, visitors at the other end of the building, hearing the noise and not knowing the reason for it, panicked and fled for the exits, having supposed the building was on the point of collapse. The duke’s confrontation with Corporal Costello is, of course, entirely imaginary.

Although there were no weather forecasts in those days, there were weather reports for the previous day. I was thus able to find out from the shipping columns of The Times what the weather was like in London on the three days of the excursion – in other words: fine, fine and wet. The excursionists were fortunate to have two fine days: the summer of 1851 was one of the wettest of the century.

The image at the head of this post is the only surviving photograph (actually, a daguerreotype) of the Duke of Wellington, taken in 1844, eight years before his death.

July 9, 2018

The Koh-I-Noor diamond – a Victorian disappointment

In 1849 the ruler of the Punjab, the 10-year-old Duleep Singh, was forced to sign over his kingdom along with the Koh-I-Noor diamond to the British.

Five years later he travelled to England, where he spent the rest of his life in exile, but not before giving Queen Victoria permission to re-cut the diamond, a permission he later came to regret and which led to his referring to the Queen as ‘Mrs Fagin’ i.e. a receiver of stolen goods. (To be fair to the Queen, she was uncomfortably aware that the diamond was loot, which was why she was anxious to secure Duleep Singh’s forgiveness for having appropriated it in the first place.)

Before the re-cutting, it was one of the star attractions in the Great Exhibition. Long queues formed to enter a kind of tent where visitors viewed the diamond in a large bird cage, where it was surrounded by gas jets intended to make it shine. It refused to oblige. Most visitors were deeply disappointed by what they saw. In the illustration below, you can almost hear them saying, “Is that it?”

Koh-I-Noor

In 1849 the ruler of the Punjab, the 10-year-old Duleep Singh, was forced to sign over his kingdom along with the Koh-I-Noor diamond to the British. Five years later he travelled to England, where he spent the rest of his life in exile, but not before giving Queen Victoria permission to re-cut the diamond, a permission he later came to regret and which led to his referring to the Queen as ‘Mrs Fagin’ i.e. a receiver of stolen goods. (To be fair to the Queen, she was uncomfortably aware that the brilliant was loot, which was why she was anxious to secure Duleep Singh’s forgiveness for having appropriated it in the first place.) Before the re-cutting it was one of the star attractions in the Great Exhibition. Long queues formed to enter a kind of tent where visitors viewed the diamond in a large bird cage, where it was surrounded by gas jets intended to make it shine. It refused to oblige. Most visitors were deeply disappointed by what they saw. In the illustration below, you can almost hear them saying, “Is that it?”

June 26, 2018

Victorian adverts

The picture at the head of this post (by John Orlando Parry) is entitled ‘The Poster Man’ and dates from 1835. Two things made this explosion of advertising possible: the growth in literacy and the invention of the steam-powered printing press. A surprisingly large number of the posters in the illustration are for theatres and concerts; in newspapers and magazines, most of the adverts would have been for quack remedies, food (particularly if it was sold in jars) and beverages. For the poster men who feared they might run out of wall space, the railways must have come as a godsend. The illustration below shows, in exaggerated form, what early railways stations much have looked like.

Many of the adverts which are plastered all over the station contain catch phrases rather than product names – catch phrases of the kind that Mr Breeze, the advertising copywriter in Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium, was paid to invent. How he came to do this for a living is told in the story attached below. It is about half an hour long, so for convenience I have divided it into two files.

https://www.stephenlycett.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/advertisers-tale-1.m4a

https://www.stephenlycett.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/advertisers-tale-2.m4a

June 17, 2018

Harrison’s Hostel

Harrison’s Hostel really did exist. Thomas Cook, who, as a temperance reformer, got into the travel business by using excursions to lure working people away from drink, persuaded Mr Thomas Harrison of Pimlico to turn his furniture depository into a hostel for visitors to the Great Exhibition. From Cook’s point of view, the venture proved a great success in that it protected ordinary travellers from the extortionate rents being charged by private landlords; from Harrison’s, it was a disaster. The hostel bankrupted him. For one and threepence per night up to a thousand residents were to be provided with bed and bedding, soap and towel. A decent breakfast was to be had for 4d, a good dinner for 8d, and for a further penny per item, the visitor might have his boots blacked, his chin shaved and his illnesses treated by a surgeon who visited every morning at nine. The dormitories were partitioned into cubicles, and, in order to prevent pilfering or drunkenness, janitors patrolled the gas-lit corridors day and night. Luxuries were not neglected either: there was a large smoking room in which a band played every evening, and on top of the building an observation platform from which visitors might enjoy uninterrupted views of the river and the city.

The two illustrations from the London Illustrated News were published to coincide with the opening of the hostel. It is hard to pinpoint the exact location of the hostel in Ranelagh Road, Pimlico, now. During the building of the Bazalgette sewers in the 1860s the Thames was narrowed and the Embankment constructed. It is clear from the picture that the hostel was on the Thames foreshore (note the wharf), a foreshore that is now some way inland.

June 8, 2018

The Adventures of Mr and Mrs Sandboys

If Henry Mayhew is remembered at all today, it is as author of London Labour and the London Poor, a series of articles on street traders, buskers, beggars and the like. He was also the editor of Punch and a novelist. Mr and Mrs Sandboys – or, to give it its full title, 1851 the Adventures of Mr and Mrs Sandboys and Family who Came up to London to Enjoy Themselves and to See the Great Exhibition – is not a great novel, but it is full of interesting period detail. The Sandboys live in Buttermere. For Mr Sandboys there is no better place on earth. Everything he could possibly want is there, or is until the summer of 1851, when he finds that there are no newspapers and no groceries, all the tradesmen and shopkeepers having gone to London to see the Great Exhibition. If the Sandboys are not to starve, they have no option but to follow. What unfolds is a story of innocents abroad. They catch the wrong train and end up in Glasgow, and when at last they are on the right train heading south they are fleeced by a conman. They are fleeced over their lodgings, fleeced by tradesmen and fleeced by just about everyone they meet. Eventually Mr Sandboys ends up in a debtors’ prison and is released the day after the Exhibition closes. He returns to Buttermere “vowing that if there was ever another Exhibition, he would never think of coming up to London again to enjoy himself.” The value of the book is not in the story – the plot is a fairly ramshackle affair – but in the portrait of London in the summer of 1851. The crowds in the streets were enormous (see the picture of Regent’s Circus at the head of this post), the pressure on accommodation intense. Visitors were accommodated in basements and garrets at outrageous cost. One of the Cruikshank illustrations show the boxes in a West End theatre being let as B and Bs. (This is surely a joke on Cruikshanks’s part, but it gives some idea of the insatiable demand for lodgings during the six months that the Great Exhibition lasted.) One answer to the lodgings problem was Harrison’s Hostel in Pimlico, which will form the subject of my next post.