Stephen Lycett's Blog, page 2

June 2, 2019

The Retrospective Destinator

The Retrospective Destinator

If you follow the link you will find an audio file of The Advertising Copywriter’s Tale (Part One). It takes about fifteen minutes to listen to. The story concerns two men who advertise themselves as follows: ‘Retrospective destinators – Messrs Hancock and Breeze offer a discreet service as makers and menders of damaged or incomplete reputations.’ The idea was suggested by a friend who told me he was all in favour of identity cards provided that every time the card came up for renewal, one had the option of changing one’s identity. This is what the story is about, but with this crucial difference: Hancock and Breeze can only change their clients’ life stories posthumously.

https://www.stephenlycett.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/6a-copywriters-tale-1-1.m4a

The post The Retrospective Destinator appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

May 14, 2019

Joseph Paxton and the Crossley Family – A Tenuous Link, but a Personal One

The photograph at the head of this blog is of the ‘peach cases’ at Somerleyton Hall in Suffolk, which I visited last week. They were commissioned in the 1840s by Samuel Morton Peto, the railway entrepreneur, and designed by Joseph Paxton, then head gardener at Chatsworth House and future architect of the Crystal Palace. One of the wonders of the age, the Crystal Palace outlived the Great Exhibition, which it had been designed to house, and was transferred (with modifications) to Sydenham, where remained until it was destroyed by fire in 1936. Paxton was a man of boundless energy and inventiveness. Of all his schemes, my favourite is the Great Victorian Way, which is described in the DNB entry on Paxton as follows:

In June 1855 he submitted his solution to London’s traffic congestion, which was a ‘girdle’, or ring road, to link up the stations, City and Parliament, lined on either side by shops, residences, and an atmospheric railway, all covered by an iron and glass roof. This visionary idea, for which a perspective drawing known as The Great Victorian Way survives at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, raised much interest, but the eventual solutions to the traffic problem were the Metropolitan Railway and the Victoria Embankment. Paxton’s scheme

Back to Somerleyton. In 1863 Peto sold the house to Francis Crossley, son of John Crossley the carpet manufacturer at Dean Clough Mills, Halifax. (Picture below.)

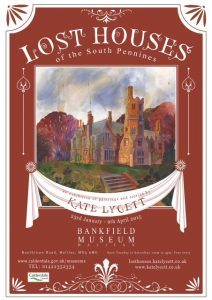

The Crossley family home in Halifax was Manor Heath, which my daughter painted for her Lost Houses exhibition in 2016, and for which I wrote the exhibition booklet. (Poster below, showing one of her pictures of Manor Heath.)

The Crossley family still own Somerleyton. Manor Heath was demolished in the 1958.

Oh, and John Crossley commissioned Paxton to design the People’s Park in Halifax, so it does all connect together. Sort of.

The post Joseph Paxton and the Crossley Family – A Tenuous Link, but a Personal One appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

April 12, 2019

The Waltz

One of the Mr Blackwood proof readers queried both the appearance of the waltz and the use of dance cards in The Corporal’s Tale, which is set in the year of Waterloo. After further research I replied to her as follows:

You’ll be pleased to know that I’ve incorporated all your amendments – bar one. And that, of course, is the waltz. I thought you might be interested in my subsequent research on the subject. The waltz was the hit of the 1812 season in London, so much so that Byron – the hypocrite! – wrote that he feared it would rot the moral fabric of the nation. It’s harder to know what went on at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball [on the eve of Waterloo], however. I read an article by a scriptwriter of costume dramas, who claimed that they didn’t dance the waltz in Brussels, where it hadn’t yet caught on, and people only think they did because that’s what happens in Vanity Fair. On the other hand, another article by Harry Mount produced a whole list of ‘couple’ dances, the waltz among them, that that featured at the ball. The Mount article is more detailed (and therefore, I presume, more fully researched), so I decided to go with that (Well, I would, wouldn’t I? Captain O’ Hare wouldn’t have been Captain O’ Hare without the waltz.) Even without the Mount article my gut feeling would have been for the waltz, because in times of danger people get – how can I put it delicately? – overheated. The final days in the Bunker in 1945 were, I believe, very lively.

You were right about dance cards, so I removed them. The earliest reference to them comes from 1803, but they were rarities until couple dancing had firmly supplanted dancing in long sets, where pairings were largely determined by social rank. That didn’t really happen until the 1830s, after which time they were a must-have at every ball and minor hop.

The post The Waltz appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

March 22, 2019

A Napoleonic Postscript

Although Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium is set in 1851, some of the stories are set in earlier periods. One of them is The Corporal’s Tale. Corporal Costello is a veteran of the Peninsula War and Waterloo. He was also in the army of occupation in Paris, which is where the events of his tale take place. I found this very hard to research. It took me a day in the London Library to track down an account of the occupation in a copy of History Today from the 1960s. All I wanted to know was where the British army – the Prussians were the other occupying force – was encamped. The answer was what I had suspected all along: namely, the Bois de Boulogne. My life would have been made much easier if Paul O’ Keefe’s brilliant Waterloo: The Aftermath had been published a few months earlier. To anyone interested in this neglected postscript to the Napoleonic Wars I cannot recommend the book too highly. The British occupation (under Wellington – picture below) was light touch, the Prussian (under Blücher – picture above) anything but. To give but one example: Blücher marched into the Louvre and seized all the pictures (including Corregios, Rubens and Rembrandts) which had been plundered by Bonaparte’s troops. Although no British gallery had been looted, Wellington was approached by the Dutch to rescue their plundered treasures. Unlike Blücher, Wellington first tried diplomacy. He approached Talleyrand, who failed to interest the newly restored Louis XVIII in the question of restitution, and only when diplomacy had failed resorted to force and placed the Louvre under martial law.

The post A Napoleonic Postscript appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

March 3, 2019

Thoughts on a Rainy Day

To escape Storm Freya I went to the Russell Cotes Museum in Bournemouth today. Both the house and its contents are an enormous splurge of Victorian bad taste. I couldn’t help noticing the buckets in the conservatory (see photo). Fair enough, I suppose, the wind and rain being so fierce, but I did wonder how watertight most Victorian conservatories were. According the memoirs of Hector Berlioz, who seems to have secured out-of-hours access, the Crystal Palace leaked. He noted several discreetly placed buckets, as well as some green streaks on the inside of the roof glass. (He also found a sparrow nesting in the muzzle of cannon.) The summer of 1851 was one of the wettest of the century, which lends credibility to a description in a Hardy short story (‘The Fiddler of the Reels’) of excursionists to the Great Exhibition arriving at Waterloo in the first stages of hypothermia, having travelled up from Wessex in open carriages.

The post Thoughts on a Rainy Day appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

February 18, 2019

There and back : A tale of two pilgrimages

Those of you who know the Canterbury Tales will know that Chaucer originally intended each of the thirty-odd pilgrims to tell two tales on the outward journey and two on the return, making one hundred thirty tales in all. Either Chaucer died before completing the scheme or at some stage thought better of it and would have substituted a more modest commitment had he lived to edit it. Nonetheless, I have often wondered whether the return journey tales would have been different in tone and character from the ones told on the outward journey, whether the pilgrims’ experiences in Canterbury, sacred or profane, might have changed them and whether those changes might have found their way into the tales they told.

In Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium it was never my intention to mimic Chaucer or re-tell any of his tales in a Victorian setting. What I did want to do was to complete Chaucer’s scheme – in other words, to have my Victorian excursionists return home in some way altered – exhilarated, disappointed, fulfilled, educated, appalled – by their experiences of the Great Exhibition. The outward stories are more traditional and are meant to have a folk tale feel to them, whilst the return journey ones are meant to seem more modern, as if the excursionists have passed through the portals of the Crystal Palace and come out laden with recognisably modern anxieties about money, class and social justice.

A last thought. I am not the only person to have wondered what the Canterbury Tales might have looked like had Chaucer complete them. An anonymous fifteenth century poet attempted to complete the story of the round trip in the fragmentary Tale of Beryn, whose Prologue describes the adventures of the pilgrims in Canterbury. For anyone interested, this is the Wikipedia link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prologu...

The post There and back : A tale of two pilgrimages appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

February 7, 2019

Pluckley

The mad wives, however, were delayed by an unscheduled stop at Pluckley. The train came to a halt between white clapboarded buildings, beyond which the rooks rose in a great clamour from the trees by the gravel pits. From our tub we could see porters assembling a goods train in the siding, a fly waiting in the station yard, its owner fast asleep on the box, and the station master’s wife trying to cut chrysanthemums from a flower bed with a pair of nail scissors. A man reading the East Kent Gazette frowned when the band struck up with ‘Elsie from Chelsea’ and positively glowered when Stumps jumped up on the seat and joined in the chorus. (Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium Chapter 2)

At one point the excursion stops – in the middle of someone’s story – at Pluckley Station. I chose Pluckley for two reasons. One, it is the only original station building remaining on the South Eastern Railway line to Dover. I imagine that all the stations between Ashford and Tonbridge (usually spelt Tunbridge in those days) – Headcorn, Staplehurst, Marden, Paddock Wood, etc. – must also have been single-storey clapboarded buildings. The other reason for stopping there was that Pluckley, reputedly one of the most haunted villages in England, was a good place to introduce Dr Erasmus leGrove, the diocesan exorcist. Pluckley is said to have ghosts of a schoolmaster, a monk, a soldier a miller, an old gypsy woman and a highwayman. For a full list see Westwood and Simpson’s The Lore of the Land.

The post Pluckley appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

January 25, 2019

A Victorian Canterbury Tales

Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium is a Victorian version of the Canterbury Tales in which the members of a Canterbury temperance society go on an excursion to the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The shrine they go to worship at – the Crystal Palace, filled with the technological marvels of the age – is a thoroughly secular one, but like Chaucer’s pilgrims, they set off in high spirits and with high hopes, telling stories en route. Unlike Chaucer’s pilgrims they tell stories on the way home, too. Chaucer’s pilgrimage stops just short of Canterbury, so we know nothing of their experiences at the shrine of St Thomas. Chaucer’s contemporaries and near-contemporaries must have wondered what they got up to when they arrived, for in the middle of the fifteenth century an anonymous poet wrote the Tale of Beryn which fills in the blank. For modern readers perhaps the most surprising thing about this work is the Pardoner’s unambiguously heterosexual pursuit of the barmaid. (Modern readers always assume that the Pardoner is gay.) Mr Blackwood gives a full account of the excursionists’ adventures in the Crystal Palace, as well as providing them with tales to tell on the homeward journey, tales which are very different in character from the ones they tell on the outward. One wonders whether Chaucer’s pilgrims would have been changed in any way by their encounter with St Thomas (or the barmaid) and whether that change would have been reflected in the tales they told. Above all, one wonders who would have won the story-telling competition. My money’s on the Merchant.

Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium is not a slavish re-telling of the Canterbury Tales – all the tales in it are wholly original – but there are parallels in the structure. The Crystal Palace and the Shrine of St Thomas are obvious parallels; so, too are Harrison’s Hostel, the furniture warehouse in Pimlico that was converted into a sort of Travel Lodge for visitors, and the Chequer of Hope, the main pilgrim inn in Canterbury, illustrated above. Built in 1392 and destroyed by fire in 1865, the latter was situated at the corner of the High Street and Mercery Lane. (A few bits remain in the facades of present buildings.) Some of the Mr Blackwood characters have obvious Chaucerian ancestors. Corporal Costello, the Waterloo veteran, and his son George, a bugler in the Buffs, are obviously related to the Knight and the Squire, ditto the musical artiste who styles herself the Duchess of Croydon and the Wife of Bath, together with Mme Fontana, the fake medium, and the Pardoner.

In 1851 the Canterbury excursionists would have taken the westerly route to London through Edenbridge and Redhill, then designated Reigate. (The modern route, completed in 1868, branches off the earlier one at Tonbridge – commonly spelt Tunbridge until the 1890s – and continues through Sevenoaks and Orpington to London Bridge. Charing Cross, the present terminus of the line, was not opened until 1864.) Chaucer’s pilgrims took the more northerly route through Rochester and Faversham, a 68 mile journey which would have taken three days. One final point: in order to allow enough time for my excursionists to tell all their tales, I had to put them on board a special, which from time to time is forced to stop at signals whilst scheduled trains go past. According to Bradshaw, the scheduled service from Canterbury to London in 1851 took 3 hours and 55 minutes.

The post A Victorian Canterbury Tales appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

January 13, 2019

Jane Eyre – A Victorian Shocker

The third story in Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium, ‘Miss Biddlecombe’s Proprieties’, describes what happens when sea bathing and a clandestine copy of Jane Eyre are introduced into a respectable young ladies’ boarding school. (You’ll have to read the story to find out what actually happens!) What is hard for us to imagine today is how shocking the Victorian reading public found Jane Eyre once its female authorship had been revealed. The strength of female emotion – not just Jane’s but Bertha’s (‘What a pigmy intellect she had, what giant propensities!’) – led to its being accused in the Quarterly Review of ‘moral Jacobinism’. Images of passion and of fire run through the novel, symbolised by the fire that burns down Thornfield Hall. On the surface Jane and Bertha might appear to be opposites, but at a deeper, emotional level Brontë hints at affinities between them.

The emotional world that Charlotte Bronte and her characters inhabit could not be more different from that in inhabited by Jane Austen and hers. Small wonder that Charlotte Bronte despised her great predecessor.” Anything like warmth or enthusiasm,” she wrote, “ anything energetic, poignant, heartfelt, is utterly out of place in commending these works: all such demonstrations the authoress would have met with a well-bred sneer, would have calmly scorned as outré or extravagant. She does her business of delineating the surface of the lives of genteel English people curiously well … But she no more, with her mind’s eye, beholds the heart of her race than each man, with bodily vision, sees the heart in his heaving breast. Jane Austen was a complete and most sensible lady, but a very incomplete and rather insensible (not senseless) woman.”

Ouch!

The post Jane Eyre – A Victorian Shocker appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

January 1, 2019

A Wuthering Heights Original

Back in August I posted a blog about my artist daughter’s exhibition on the Lost Houses of the South Pennines in Halifax. (If you want to check it out, it’s the one that begins: Whilst I was nearing the end of Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium in early 2016, I had to take time out to write the text for Lost Houses of the South Pennines, the booklet (later a book) which accompanied my daughter’s exhibition at Bankfield Museum in Halifax.) One of the houses that I didn’t mention in that blog was High Sunderland, near Halifax. I was reminded of this by last Saturday’s Channel 4 programme, presented by Lily Cole, on Emily Bronte.

Today High Sunderland is remembered mainly for its Bronte connection. In 1838 Emily spent several months teaching at Law Hill School in Southowram. Although she disliked the School, she was fond of the countryside and her walks would have taken her past High Sunderland, which was little over a mile away; indeed, the similarity between the floor plan of the Hall and that of Wuthering Heights has led some to suggest that she might even have been a guest of the Wood family who then occupied it. But it would be wrong to suggest that the fictional house is modelled, point for point, on the real one. Top Withens, a hilltop farm near Haworth is said to represent the location of Wuthering Heights and Ponden Hall, also Near Haworth, to contain many of its interior details. What she borrowed from High Sunderland were the carvings. In the novel, Lockwood, the narrator, describes his first entrance into the house: ‘Before passing the threshold, I paused to admire a quantity of grotesque carving lavished over the front, and especially about the principal door: above which, among a wilderness of crumbling griffins and shameless little boys, I detected the date 1500 and name of Hareton Earnshaw.’ The name and the date are flights of fancy, but the griffins and shameless little boys surely belonged to the great gateway, whose remains are still waiting to be re-discovered in Brighouse. And if the architectural details were not enough, there is the ghost story. Tradition has it that anyone sleeping in a certain room at High Sunderland would awake at night to hear footsteps in the corridor and a rattling of the doorknob. The door proving secure, the rattle at the door would be replaced by a tap at the window. If the inhabitant of the room – now wide awake – looked out, he or she would see a disembodied hand striking the glass and hear a peal of hideous laughter. The hand, it was said, was that of an ‘estimable and virtuous lady’ and had been cut off by her husband in a fit of insane jealousy. This tale must surely form the basis of Lockwood’s dream in Wuthering Heights:

‘I heard also the fir bough repeat its teasing sound … it annoyed me so much that I resolved to silence it, if possible; and I thought I thought I rose and endeavoured to unhasp the casement. The hook was soldered into the staple … “I must stop it, nevertheless,” I muttered, knocking my knuckles through the glass, and stretching out an arm to seize the importunate branch; instead of which, my fingers closed on the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand! The intense horror of nightmare came over me. I tried to draw back my arm, but my hand clung to it, and a most melancholy voice sobbed “Let me in – let me in!”

High Sunderland – or some of it, at least – lives on in Bronte’s novel. The real house was not so fortunate. A report written for the Bronte Society in 1949 paints a sad picture of it in its death throes:

‘Originally the gateway opened into a courtyard and later on to a paved path leading to the main door. The path is now overgrown with grass and weeds and littered with empty milk bottles, rusty cans and broken chair legs. The pillars to the entrance of the main door are leaning at a precarious angle. Above them were two statues: one survives, disfigured almost beyond recognition; the other, broken into three pieces, has fallen to the ground alongside the rusty frame of a discarded motor cycle. The visitor who ventures through the interior of High Sunderland will find desolation reminiscent of a bomb-shattered building. No windows exist; some of the window spaces have been boarded up but the wood has rotted. The floors are littered with broken stonework, splintered rafters, tiles and here and there pieces of abandoned furniture. Rubbish has, in fact, been discarded indiscriminately, most likely when the last tenants vacated the building. It is unsafe to subject the walls to any weight for they are likely to crumble. The only light in some rooms comes from large holes in the roof and through missing stones in the wall. The uncanny howl of the wind as it whips though gaps in the stonework produces an atmosphere that chills and depresses.’

Two years later High Sunderland was demolished.

The post A Wuthering Heights Original appeared first on Stephen Lycett.