Stephen Lycett's Blog, page 3

December 15, 2018

Fern Mania

In Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium Mr Malachi Brown, who gets on the train at Tunbridge, is introduced to his fellow passengers as ‘the eminent pteridologist’. So what was pteridology and how did one become eminent in it? In 1855, the Rev Charles Kingsley, author of The Water Babies, wrote: Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing ‘Pteridomania’…and wrangling over unpronounceable names of species (which seem different in each new Fern-book that they buy)…and yet you cannot deny that they find enjoyment in it, and are more active, more cheerful, more self-forgetful over it, than they would have been over novels and gossip.

These remarks seem to us highly sexist. They are also inaccurate. Fern mania crossed class and gender barriers. The collection of ferns drew enthusiasts from all social classes and it is said that “even the farm labourer or miner could have a collection of British ferns which he had collected in the wild and a common interest sometimes brought people of very different social backgrounds together”.

It began in 1829, when British surgeon and explorer Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward invented the Wardian case, a table top mini-greenhouse that kept exotic plants alive in the cold, damp British climate. (We know it as the terrarium.) His invention allowed botanist George Loddiges to build a huge hothouse in East London, which included a fern nursery. Even though the plant was associated with fairies and magic – “We have the receipt of fern seed: we walk invisible (Shakespeare, Henry IV Part I) – Loddiges knew that he needed to exaggerate the properties of ferns to attract visitors to his hothouse. Fern collecting, he claimed, showed intelligence; it also improved virility and mental health. With claims like that, who could resist becoming a collector?

New discoveries were published in periodicals, particularly The Phytologist: a Popular Botanical Miscellany which first appeared in 1844. Having been studied less than flowering plants, ferns were open to new sightings and recordings. That was undoubtedly part of their attraction. Another reason for the craze was that, with the development of the railways, the wetter western and northern parts of Britain – areas where ferns were most diverse and abundant – were becoming more accessible. So much so, in fact, that some species were collected to the point of extinction.

Ferns and fern motifs appeared everywhere: in homes, gardens, art and literature. Their images adorned rugs, tea sets, chamber pots, garden benches and even custard cream biscuits. Wardian cases soon became features of stylish drawing rooms all over Europe and the United States and helped spread not only the fern craze but the craze for growing orchids that followed. Ferns were also cultivated in fern houses and in outdoor ferneries.

Mr Malachi Brown likes to think of himself as a serious evolutionary biologist. But there is no money in serious evolutionary biology – at least not before Darwin published the Origin of Species in 1859 – so Mr Malachi Brown has, to his disgust, to earn a living by pandering to a popular fad.

The post Fern Mania appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

December 1, 2018

Railway Navvies

The first tale in Mr Blackwood is told by the Waterloo veteran, Corporal Costello, and the second by Stumps, the railway navvy. This pairing was intended to echo the first two Canterbury Tales, where the Knight’s tale, much to the irritation of the Host, is followed by that of the oafish Miller. The world of the navvies is a fascinating one. One of the most comprehensive accounts is contained in Terry Coleman’s 1965 book The Railway Navvies. A much earlier account is that of the Rev D.W. Barrett MA published in 1880 and entitled Life and Work Among the Navvies. In his foreword Barrett writes: “This little sketch is written with several objects in view. One is to supply a record of a special undertaking in railway work, and an account of the manners and customs of the ‘navvies’ and railways labourers in general, who are employed in making new lines. Another is to call attention to some encouraging features of the Church amongst them.” Ah, the Church. Barrett, like so Victorian clergymen, saw the navvies as both a challenge and an opportunity. In the navvy encampments, where drink, prize fighting and promiscuity were said to be rife, there were rich pickings to be had by way of conversion and moral reformation. Such efforts were not always welcomed by the navvies, though, to be fair, some clergymen were genuinely concerned for the material as well as the spiritual welfare of the navvies and their families.

A rich visual source for the life the navvies is the work of the artist J.C. Bourne, who published sets of engravings of the building of the London to Birmingham Railway and the great Western. For anyone who has never seen his work, it is well worth a Google. Illustrations above and below.

The post Railway Navvies appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

November 19, 2018

A Short Biography of Dickens’s Face

Until the 1840s Charles Dickens was, like most early Victorians, clean-shaven. In 1842, he travelled for the first time to the United States where he met Edgar Allan Poe, at that time the owner of a fine but restrained moustache. Dickens was smitten and quickly grew one of his own. (Moustaches were often referred to in the plural, as in ‘a pair of moustaches’). “The moustaches are glorious,” he wrote, “glorious. I have cut them short, and trimmed them a little at the ends to improve their shape. They are charming, charming. Without them, life would be a blank.”

Moustaches were also given respectability by Prince Albert who sported a neat one throughout his adult life. The beard craze began in the mid-1850s. Until then soldiers had not been permitted to grow beards, but the rigours of the Crimean winters made it impossible to obey the rule, with the result that most soldiers in the war grew them, and it was they who, on returning home, set the fashion amongst civilians, Dickens included. (Prince Albert stood firm and stuck to his moustache.)

Beards quickly sprouted – if that’s the right word – variants such as mutton chop whiskers and the absurd dundrearies, named after Lord Dundreary, a comic character in the play ‘Our American Cousin’ by Tom Taylor. (This, incidentally, was the play the bearded but unmoustached Abraham Lincoln was watching when he was assassinated.)

Dickens died before his face could come full circle. By the 1880s the craze for beards was dying out. Think of Sherlock Holmes. He first appeared in 1887 and was, according the original Sidney Paget illustrations, definitely clean shaven.

In ‘Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium’ most of the male characters would have been either clean shaven or moustached. Had the Great Exhibition been held five years later, most of them would have been bearded.

The post A Short Biography of Dickens’s Face appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

November 4, 2018

Exit through the Gift Shop

As far as I know there wasn’t a gift shop in the original Crystal Palace, thought there may well have been one in its successor in Sydenham. But if there wasn’t a souvenir shop, there was no shortage of souvenirs. My great grandfather, who was an exhibitor, brought home a paperweight. This object, which lived for many years on my grandparents’ mantel piece, first kindled my interest in the subject of the Great Exhibition. Visitors would have bought souvenirs from vendors outside the building in Hyde Park. (Postcards were displayed in upturned umbrellas by the railings.) I don’t know if anyone has ever compiled a definitive list of the merchandise available, but I have come across commemorative trays, pomade pots, fans, medals, visiting card cases, mugs, jugs and plates. The illustration is of an item I found recently on the internet. It is a lady’s glove with a map of Hyde Park printed on the palm. Not a bad idea, now I come to think of it. I’m sure that would be a marketfor gloves with London Underground printed on them.

The post Exit through the Gift Shop appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

October 24, 2018

Tales from the Cutting Room Floor

In the course of my researches for the book in the London Library I came across many wonderful historical details which I would have loved to have included, but was self-disciplined enough to reject. I had to keep reminding myself that what mattered was the tale I was trying to tell and that I must not let it be impeded by historical clutter. Here are three examples:

The first tale in Mr Blackwood, A for Augustus, is set during the brief allied occupation of Paris after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. I wanted to find out where the British army was billeted, a detail which proved extraordinarily elusive. (The answer, by the way, is the Bois de Boulogne.) In tracking it down I discovered that Paris, like Berlin in 1945, was divided into occupation zones, the British occupying one part and the Prussians the other. Fortunately for the Parisians, the Pont de Jena was in the British sector, because the Prussians were determined to blow up a bridge which had been named after their catastrophic defeat by Napoleon in 1806. So bent on revenge were they that the British had to mount permanent guard on it. I longed to write in a scene in which the bridge was saved from destruction by plucky Brits. It wouldn’t have been relevant to the story, so I had, alas, to leave it out.

Once the excursionists have arrived in London they take the steamer to Pimlico, where they are to stay overnight. On the way they pass the half-completed Palace of Westminster. The new clock tower prompts the watchmaker to tell his story about what he regards as the tyranny of Greenwich meantime. It is well known that Greenwich meantime was rolled out across the country on railway guards’ watches. Until the railways there had been different times in different parts of the country – Plymouth, for example, was three minutes ahead of Greenwich – but to function smoothly the railways needed uniform time. That claim is true as far as it goes, but what it doesn’t account for is how the railways got the correct time in the first place. For nearly forty years a splendid lady, whose name I can’t now remember, set a stop watch in Greenwich and then visited every London clockmaker with it in the course of the day. The clockmakers had to display a card in their windows to certify that they had signed up to this arrangement, an arrangement that lasted, astonishingly, until the 1920s when either the lady grew too infirm to carry on, or the wireless rendered it redundant. (Or possibly both.) I would have loved to have included her in the Watchmaker’s Tale, but it would have needed a huge detour from the main narrative to get her on board.

One final example from the cutting room floor. Lord Palmerston’s tale is set in Venice, which in 1848 had declared its independence of Austria. As a symbol of its independence it printed its own money – moneta patriottica. When the Austrians re-took the city in 1850, they burned the money in a huge cauldron in St Mark’s Square. All this I managed to include in the story. What I didn’t manage to include was the story of General Ludwig Haynau. He was responsible for the wave of savage repression and reprisal that followed. Not for nothing was he nicknamed ‘the Hyena’. There was outrage in in Britain at the hangings and floggings he ordered, especially as some of the victims were women. In 1851 Gen. Haynau came to Britain and, among other places, visited Barclay’s brewery in Southwark, where he was beaten up by the workers. Queen Victoria, who had supported the Austrians throughout the insurrections of 1848, demanded that the Government send an apology. The Foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, who had supported the insurgents, was privately delighted by the attack in Southwark and delayed sending a very half-hearted apology. Good for Palmerston, say I.

The post Tales from the Cutting Room Floor appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

October 15, 2018

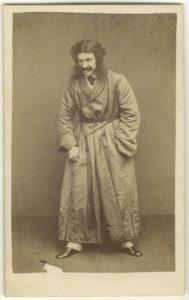

A Theatrical Comet

Edmund Kean was the greatest Shakespearean actor of his day. His performance as Shylock at the Drury Lane Theatre in January 1814 – he was then twenty-seven – is said to have roused the audience to almost uncontrollable enthusiasm. The poet Coleridge famously said, “Seeing him act was like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning.” Successive appearances as Richard III, Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth and Lear served to demonstrate his complete mastery of the whole range of tragic emotion. His triumph was so great that he himself said on one occasion, “I could not feel the stage under me.” Dead by the age of forty-six, he was the proverbial meteor, rocketing to fame and fortune which he squandered in loose living and drink. His last appearance on the stage was at Covent Garden, on the 25th of March 1833, when he played Othello to the lago of his son Charles. At the words “Villain, be sure,” in Act 3 scene 3, he suddenly broke down, and, crying in a faltering voice, “O God, I am dying. Speak to them, Charles,” fell insensible into his son’s arms. The story of his death appears in Mr Blackwood’s Fabulorium, where it is acted out by the actor Cyril Purselove before an admiring crowd, in the street outside Harrison’s Hostel in Pimlico. After Kean’s death the Shakespearean crown passed to William Macready, to whose Macbeth Purselove claims to have played Banquo.

The post A Theatrical Comet appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

October 1, 2018

George Measom’s Guide to the South-Eastern Railway

Whilst writing Mr Blackwood I was able to visualise a good deal of the train journey with the help of George Measom’s Guide to the South Eastern Railway, which was published in 1853, two years after the Great Exhibition. It is a typical Victorian travel guide, similar to the ones published by George Bradshaw. It doesn’t, unfortunately, say much about the railway itself, but concentrates on historical buildings – especially churches – and monuments. The Canterbury entry, unsurprisingly, is taken up by a long description of the Cathedral.

The book begins: “The South-Eastern Railway is one of the most important lines in England, opening in the first place a direct and rapid communication with the Continent by way of Folkestone and Dover, and visiting on its road many important stations connected with populous towns and thriving rural districts, affording also a rapid means of transit to several favourite watering places which before its establishment were virtually at a day’s distance from London instead of three or four hours.”

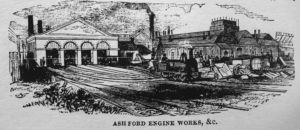

The principal interest of the book lies in its illustrations, many of which are of stations on the London to Canterbury line. Here is a selection of them. The illustration at the head of this post is of a train leaving Canterbury station.

Ashford Engine Works

Paddock Wood Station

Tunbridge Station

Reigate Station

The Greenwich Viaduct which the travellers would have seen to their right as they approached London Bridge

The inside of London Bridge Station

The outside of London Bridge Station seen from Tooley Street

The post George Measom’s Guide to the South-Eastern Railway appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

September 23, 2018

What Else Happened in 1851?

Lord John Russell was Prime Minister – Lord Palmerston resigned as Foreign Secretary in December – The window tax was repealed – Lajos Kossuth, hero of the 1848 revolution in Hungary, arrived in England – The first submarine cable to Calais was laid – Landseer painted The Monarch of the Glen and Millais Mariana – Ruskin championed the Pre-Raphaelites – Macready played Macbeth for the last time -Marble Arch was moved to its present location from its original site opposite Buckingham Palace – David Livingstone reached the Zambezi – The Derby was won by the 3-1 favourite Teddington and the Grand National by Abd-el-Kader – JMW Turner died – Mrs Bloomer toured Britain advocating the wearing of pantaloons by women.

The post What Else Happened in 1851? appeared first on Stephen Lycett.

September 13, 2018

Building the Crystal Palace

I was going to write a post on the design and building of the Crystal Palace, Joseph Paxton’s masterpiece, but then I discovered this wonderful sequence on Youtube. In a future post I will describe how the Hyde Park version of the Crystal Palace was dismantled after the Great Exhibition and taken to Sydenham where it was re-assembled and, I’m sad to say, ruined. In the meantime, enjoy the link:

August 29, 2018

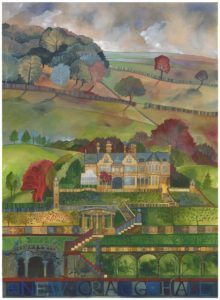

Lost houses reveal intriguing stories

Whilst I was nearing the end of Mr Blackwood’s Fabularium in early 2016, I had to take time out to write the text for Lost Houses of the South Pennines, the booklet (later a book) which accompanied my artist daughter Kate’s exhibition at Bankfield Museum in Halifax. The houses in question – there were ten of them – have disappeared, in some cases without trace, or been reduced to a few scattered stones. Had I started the project earlier, some of the stories might have found their way into Mr Blackwood.

Take, for example, the story of New Cragg Vale (picture below). Of Hinchliffe Hinchliffe’s mills near Mytholmroyd, the local rector wrote: ‘If there is one place in England that needs legislative interference it is this place; for they work 15 and 16 hours a day frequently, and sometimes all night. Oh! it is a murderous system and the mill owners are the pest and disgrace of society…!’

Workers were fined for unpunctuality, children beaten for minor misdemeanours. Small wonder, then, that the most hated name in Cragg Vale was that of Hinchliffe Hinchliffe. He died as a recluse in Southport and was survived by only one of his five children, Helen. Although she was said to have been spoiled by her father, she grew up to be very different in outlook. She was married three times. Her third husband was a 22 year old bank clerk from Harrogate named William Algernon Simpson. Helen Hinchliffe was then 48. William Algernon Simpson (or Algy Simpson-Hinchliffe, as he chose to be known) initiated a new social era in Cragg Vale. Between 1904 and 1906 he extended and re-modelled Hinchliffe Hinchliffe’s house at Cragg Vale. He and his wife spent lavishly – and not just on themselves. Newspapers of the time reported eagerly on tea parties, picnics for the workers and social events for schools and clubs: ‘Christmastide was again celebrated with no unstinted hand by Mr and Mrs Simpson-Hinchliffe. A beautiful tea was in the school for the children, after which they were invited into the upper room, and as they entered it their breath was almost taken away with the glorious sight which met their view. Standing in the middle of the room was a huge Christmas tree, from which were suspended toys of almost every imaginable character. These were given to the children along with a tin of Harrogate toffee and an orange.’

A further report tells how Algy, dressed at Father Christmas, accidentally set his beard alight and badly burned his face. How unlike the days of Hinchliffe Hinchliffe, who is said to have charged guests for the cigars he offered them! Unlike almost all the other houses in the exhibition, New Cragg Hall did not endure a lingering death by neglect and decay. In the early hours of August 11th 1921 it caught fire and within a few short hours it was nothing but a blackened ruin, its roofless gables outlined starkly against the sky.

Or take the story of Castle Carr (picture top), built between 1859 and 1867 near Luddenden Foot by Joseph Priestly Edwards, Deputy Lieutenant of the West Riding and Captain in the West Yorkshire Yeoman Cavalry.

It was intended as a country residence and shooting lodge. No expense was spared and no taste shown. Everything was conceived on a vast scale. Visitors entered through a Norman arch, which contained a portcullis and to which a keeper’s lodge (with clock tower) was attached. Having alighted from their carriages, they climbed a handsome flight of stone steps, which were flanked at the top by two life-size crusaders, and then through a carved stone screen into an Ante Hall, to be greeted by yet more stone crusaders. To the right of the Ante Hall was the Great Banqueting Room, whose walls were covered with carved panels and whose focal point was a massive stone fireplace with marble pillars, carved capitals, tessellated hearth and moulded stone fender. Opening out from the opposite side of the Ante Hall was the Picture Gallery, which contained a similar wealth of decoration and which led in turn to the Grand Staircase with its elaborately carved balustrades, each newel post being capped with a carved Talbot hound. At the head of the staircase was the Gallery, which allowed access to the Sitting Room, the Billiard Room and the Library, all of which had their share of Talbot hounds and carved hunting scenes. Captain Edwards did not, alas, live long enough to enjoy the baronial splendours he had created in the Luddenden Valley. He and his eldest son, Priestley August, were killed in the Abergele railway disaster of 1868, as they were returning from a weekend shooting party. So badly disfigured was he that his body could only be identified by his keys.

The story of many of the houses is the story of the rise and fall of the mill-owning families who built them. For anyone interested in following the two stories above in more detail, as well as the stories of all the other houses, go to my daughter’s website: www.katelycett.co.uk