Larry Brooks's Blog, page 8

October 2, 2017

Text, Lies and Worn Out Old Tapes – Hearing Is Not Believing

An Essential Post of Monstrous, Manifesto Proportions

I’m on fire about this topic. I’ve written various iterations of it, sometimes using the words “The Lie” within the title. I even have a little ebook by that title. It’s an attention grabber, one that some writers take as a challenge to disprove, because hey, that’s the way they do it. And if they do it, how can it possibly be a lie?

This site is about both process and product. But you’ll always be clear on which side of this dichotomy you are dealing with, and you’ll get the clearest, most succinct and actionable accounting of the parts and parcel and structure of a novel available anywhere, from anyone.

Beginning in October, Art Holcomb will be joining Storyfix as a regular contributor (he already has over two dozen posts here on Storyfix; use the Search function to the right to check them out). Art is perhaps the best teacher of process I’ve met, and his stuff works because it it based on a keen understanding of what a story needs to do, in what order, using specific techniques to elicit specific reader experiences and engagement.

Meanwhile, I’ll be here writing about the cogs in the story machine, the nuts and bolts and rivets and cylinders and belts that put drama and character into motion within our stories.

Together, our goal is to leave no stone unturned for writers who want to learn this craft from the inside out, instead of just waiting for lightning to strike from a good idea.

Today’s post (see below) first ran on WriterUnboxed.com a few months ago.

Read it here, then go to that site and check out the interesting comment thread. Including the guy who claims anything he’s ever heard about writing that’s useful could fit on a 3 by 5 card.

That’s what I’m talking about. That guy. Telling The Lie.

******

The Well-Intentioned, Feel Good Untruth About Writing Compelling Fiction

Welcome to The Big Lie

By Larry Brooks

There’s a quiet rumor circulating among newer writers that professional authors know something they don’t. And that those famous A-listers (B-listers, too) aren’t giving it up.

This may very well be the case. Not so much as a conspiracy, but from a lack of an ability to convey—or a willingness to admit—that what they do can actually be explained, or that it can be taught and learned.

Too often they say this instead:

“I just sit down and write, each and every day, following my gut, listening to my characters, and eventually the magic happens.”

And so, hungry writers who hear this may lean into the belief that the craft of writing a good novel is inexplicable. That it’s something we are born with, or not. It is purely an issue of instinct. Maybe even that your characters actually talk to you.

The nights can get pretty long if you’re waiting to hear voices.

The real dream killer takes wing when writers conclude that there really isn’t anything to know at all. Rather, that you get to make it all up as you go.

And thus the Big Lie is born.

There actually is an enormous wealth of principle-based learning to be discovered and assimilated about how to write a novel that works. And there are folks out there teaching it, albeit with different models and terminology… all of which tends to coalesce into a singular set of interdependent truths.

Maybe it’s not a lie when someone repeats what they believe to be true. But belief, especially about the underpinnings of writing fiction, doesn’t make something true.

It may indeed be true for them. But not necessarily true for you.

Clarity requires understanding the differences.

There is no default best way to write a story, nor is there a prescribed path. Anyone who tells you that organic story development is superior to structured, principle-driven story development, including outlining, is wrong, regardless of their belief in that position.

And vice versa. Both are issues of process, and only that. They are choices, rather than an elevated version of conventional wisdom.

But with finished stories, any division between process and product vanishes. At that point, when you deem a draft to be final, what is true for one writer is suddenly true for all.

Clarity awaits in understanding the difference not only between process and product, but between rules and principles, as well. Rules apply to neither, while principles empower both.

Whether by intention, as a product of instinct or pure blind-ass luck, the efficacy of fiction is always driven by a set of core principles. They are not something you get to make up as you go. Rather, they are discovered as you progress along the learning curve.

Not all authors recognize the inherent opportunity in that moment of discovery. Sometimes they need to see the principles at work within someone else’s story… which is the most validating teachable moment of all.

The Author Who Can’t Tell Us Anything

In a recent author profile appearing in Writers Digest Magazine, an 11-million-copy bestselling author confessed she has no idea how she does it. Clearly, after two movie adaptations on top of her book sales, the numbers prove her wrong.

But not knowing how she got there isn’t saying she doesn’t know what it needs to look like when she does. The numbers prove that, as well.

So what is she hiding? Is she lying, is she confused, or is she truly without a clue?

Probably none of the above. Rather, her contention is simply proof that, as it is in many forms of art and athletics and academics, doing and teaching exist as different core competencies, only rarely shared within one practitioner.

One might also cynically suggest that this actually proves one doesn’t require any core knowledge to knock a story out of the park. You just need to put in the time, and eventually your instincts will kick in.

Maybe. It happens. But usually it is more complicated than that.

Whether they know it or not, teachers who never circle around to the core principles of fiction as a part of the creative process are peddling the Big Lie.

They will defend their seat-of-the-pants blind process vigorously from behind a keynote podium, yet they have no explanation beyond the principles—which they aren’t talking about—that led to their own writing success.

It’s like your kid designing a paper airplane. It flies, even though Junior knows nothing about aerodynamics. And while you might think this proves the other side’s point, it doesn’t. Because the complexities of a novel that works are more like a Boeing airliner than a paper airplane from kindergarten.

As writers, we don’t know what we don’t know.

When I started writing about writing, I ran into a guy on an online forum who proclaimed this: “I never outline. It robs the process of creativity and the possibility of discovery. It takes the fun out of it.”

So says… that guy. Who is in it for fun.

This may be true… for him. This absolutely is not—it never has been—a universal truth you should apply to your own experience… at least until you should.

The things we don’t know become the learning we need to seek out and discover and understand before we can begin to truly wrap our heads around fiction as a profession. Writing itself is certainly a viable part of that journey, but it is not what unlocks the secret of that journey, in and of itself.

That forum guy was talking about his process, irresponsibly framing it as conventional wisdom. But there are no universal truths when it comes to process, other than it needs to take you somewhere, and that yours might indeed be what is holding you back.

Story doesn’t trump structure. Just as structure doesn’t trump story. Because they are the same things. Both are extreme ends of a process continuum that, if and when it works, takes you to the exact same outcome. Anyone telling you differently is actually talking about their own preferred process, and if they don’t clarify that context then they are propagating the Big Lie.

And thus a paradox has been hatched.

So if not everyone agrees, how then do we pursue the core craft we need to write a novel that works, whatever our process? Even if the folks we admire and look to for answers claim they don’t?

Take the common advice to just write.

Depending on the degree to which the writer commands the core principles, it may be like telling a medical student to just cut. “Just write” is half of the answer, for half of the problem, applying to half of the writers who hear it, sometimes long before they should even consider it. Any more than a first year medical student should consider removing a spleen from anything other than a cadaver.

Because just write is advice about process, not product. Yet when Stephen King advises us to do it, who dares question him… even when they should?

Such advice, framed as truth, becomes yet another part of the Big Lie.

Welcome to the writing conversation.

This seems to be how the entire writing conversation—blogs, books, how-to articles, workshops, conferences, keynote addresses, famous writer profiles, writing groups, critique groups, and (God-help us) writing forums—is framed. And yet, collectively, combined with practice and a seat-of-the-pants ability to assimilate skill and truth as it collides with what we would rather deem to be mystical and elusive, there are things that actually do define the journey of learning to write a professional-caliber novel.

Look in the right places and you will indeed encounter specific principles, propositions, processes, expectations, categories, models, trends and risks that the more experienced writer understands and weighs—perhaps only at an instinctual level, but they exist nonetheless—and that over time the effective writer builds their work upon. Most of them being issues with which the newer writer struggles.

Knowing where you stand relative to these core truths can save you years of exploration and untold buckets of blood seeping from your forehead. Some writers toil for decades without ever truly hearing these truths, or assimilating it if they do.

This is because The Lie is loud, downing what it is you truly need to hear and understand. Because even within The Lie, those truths are at work behind a curtain of hubris or ignorance, sometimes both.

Here is a framework for your learning curve, in a nutshell.

These six things rationalize the consideration of craft itself.

Not all story ideas are good story ideas. Not all of them work. You can’t sit down and write anything you want and expect it to be saved by your brilliant prose. A worthy story idea needs to seed the landscape for the things that do, indeed, cause a fully formed story to work. There are principle-driven criteria in this regard that will inform your story selection instincts, which in turn will help you sort out which is which.

While I have no data for this other than a collective consensus among agents, editors and those who do what I do… consider that half of all rejection can be explained with a recognition that the story idea, at its most basic conceptual level, may be inherently weak. Regardless of how well the story is written or how talented the writer.

A manuscript that seeks to discover the story enroute is at best a draft, and almost never a fully-formed, publishable novel. To label such a draft final, without rewriting it from the context of a fully-discovered story, is to condemn it to compromise.

There’s nothing wrong with using drafts as a search and discovery process. It’s called “pantsing,” and it works for many. It also sends many others to an early writing grave, because they don’t recognize it for what it is: a story search process, one of many that are available.

When the story is finished, and when it works, process ceases to count for anything. The exact same criteria for excellence apply to the end product, regardless of the process. You need to write with an ending in mind if you want the journey toward that ending to work.

Genre fiction is not “all about the characters.” Some gurus say this… they are wrong, or at best only partially right. Genre stories are about how a character responds to a calling, to the solving of a problem, via actions taken and opposition encountered, thus creating dramatic tension that shows us the truest nature of who they are.

In other words, genre stories are driven by plot. And a plot doesn’t work without a hero to root for and an antagonistic force to fear. In any genre, conflict resides at the heart of the fiction writing proposition.

It isn’t a story until something goes wrong. Carve this into the hard plastic that surrounds your computer monitor.

A story isn’t just about something. Rather, it is about something happening. Theme and setting and history and character need to be framed within the unspooling forward motion of the narrative along a dramatic spine, driven by things that happen, rather than a static snapshot of what is.

Structure is omnipresent in a story that works. Structure is, for the most part, a given form, not a unique invention to fit the story you are telling. This is the most often challenged tenant of fiction, and the most enduring and provable. Exceptions are as rare as true geniuses.

Structure is not remotely synonymous with formula. But the lack of structure is almost perfectly synonymous with finger painting.

The sooner you get these six truths into your head (among others, including the drilled-down subsets of each principle), the sooner you can truly begin to grow as a storyteller. And when you do, you may find yourself saying this: “Dang, I wish I’d have understood this stuff earlier in my writing journey, instead of all these years of sniffing around the edges of it, believing the wrong things from the wrong people.”

The truth is out there.

But not everyone is talking about it. Because the truth is less mysterious and glamorous and self-aggrandizing than the notion that successful writing is a product of suffering for one’s art.

Hiding beneath the under-informed meme of “there are no rules,” some writers, in the pursuit of that suffering, settle on accepting that few or none of those truths exist. That truly, good storytelling is simply the product of possessing a sense of things. That there are no criteria or expectations.

The only part of this that is true is when a sense of things refers to the degree to which the writer has internalized those six principles and all of the subterranean layers of them that exist.

Let me just say it outright: before you sit down to write a novel the way that Stephen King or James Patterson or the author giving the keynote address writes one, make sure you actually can do what they do and know what they know.

Intention is not the primary catalyst of success.

Some of the best novels, and novelists, are outcomes of a process that makes too little sense, and/or takes decades of blood, sweat and tears, and even stretches the boundaries of the principles themselves.

Rather, it is in the application and nuanced manipulation of what is known to render a novel compelling. Talent is nothing other than an ability to see it when you finally land on it, and to pursue it with awareness. Within genre fiction especially, this set of story forces is established and easily visible. It explains why James Patterson and Nora Roberts and a long list of other novelists can bang out six or more novels in a year, even without a co-author… because they know.

Principles can be taught, and they can be learned.

And certainly, there are gradations in the application of them, in the midst of contradictory opinions about all of it colliding loudly within in the writing conversation itself.

Those gradations and shadings are the art of writing a story. The raw grist of what makes a story tick, however, comprises the craft of writing one.

Know the difference, and you’ll begin to see through The Big Lie.

The post Text, Lies and Worn Out Old Tapes – Hearing Is Not Believing appeared first on Storyfix.com.

September 16, 2017

A Few Storyfix Updates

Greetings. I know I’ve been MIA for a while now… my apologies. I also know I led with this exact opener a few months ago… embarrassing. I get it.

Colleagues are telling me I’ve basically lost equity in this site. I prefer to think of it as hitting the Pause button. I’ve never intended to abandon Storyfix, my intention since the beginning of the year has been to reinvent, revitalize and relaunch it.

Why all that? Because after nearly 1000 posts (over 700 of which remain available here), it began to feel like I’ve lined all available walls with thoughts and teaching and modeling and case studies for all facets of craft and process. I found myself getting entrenched in an unwinnable debate about the continuum of process options, and frankly found the discussion frustrating.

I needed to step away. And while I’ve been away (I’ve still been out there teaching at workshops around the country, which is the absolute highest level of what I do on several levels, as well as posting on a few other websites), my resolve to teach writing the right way, the smart way, the enlightened way, has clarified.

Because you see, the writing process is negotiable. The underlying principles of craft – what makes a story work – are not. The key to everything, especially for newer and/or struggling writers, resides in understanding the core and the nuances of that statement.

I return to the battle emboldened. Less tolerant of ignorance. Willing to call out the bullshit (and it’s everywhere) when I see it put forth. More committed to helping writers see through the fog of the conventional writing conversation by providing principles, tools, examples, and processes that elevate and empower, rather than reinforce stagnation and frustration.

There will be a refurbished story analysis service, as well, priced to deliver the highest value for serious writers available anywhere on the internet.

Thanks for your patience. This is going to be an intense, wonderful and rewarding ride on both sides of the PUBLISH button.

*****

Art Holcomb to join Storyfix on a more regular, visible basis.

Art and I view the storytelling proposition through a very similar lens. If you don’t know Art, use the search function here to find his guest posts (nearly 30 of ’em), and click here to see his website, where you can access his highly regarded audio training programs.

Art will be posting here more regularity, appearing at least twice a month. That’s in addition to my posts, which will appear at least a month, as well.

The result will be the most advanced craft thinking available on the internet, targeting all levels of knowledge and experience. There are no cloud-dwelling muses here, urging you to channel your inner consciousness and listen to what your characters are telling you. A crashing silence awaits if that’s how you write.

Rather, what you’ll get here is fierce hardcore story craft. The principles that underpin it. Delivered by two literary linebackers (have you seen us?) waiting to flatten whatever lack of understanding or misinformation stands in your way.

*****

October Workshops

I’m booked for two October workshops, at this writing:

Central Ohio Fiction Writers (an RWA sanctioned group)

Saturday, October 21, 2017 – Columbus, Ohio

An all-day class, delivering a comprehensive deep dive into differentiating craft, applicable to all genres, with a focus on romance and adult contemporary love stories.

And then, the annual…

Writers Digest Novel Writing Conference

Friday and Saturday, October 27/28, 2017 – Pasadena, California

Two sessions: Concept/Premise as the differentiating story essence (Friday), and Raising the Bar on Your story (Saturday).

Click HERE to view the conference website, see all 30 presenters and the full schedule.

*****

Blog to Book – an interview by Nina Amir

Check out this article/interview that appeared on Nina’s site, wherein I wax nostalgic about how Storyfix, the blog, became Story Engineering, the book. If you’re a blogger as well as a novelist or screenwriter, you might find you’re already nursing an opportunity to find yourself in the nearest Barnes & Noble.

Click here to check it out.

*****

New training videos coming this fall.

You may be aware that I have five video training modules out. More are in the pipeline, arriving later this fall.

Art Holcomb has new audio-based training (with workshops) and ebooks on a regular basis. Click here to see his latest.

*****

Storyfix to undgo a facelift.

I’m vetting designers now to bring a fresher look to this website.

I’m also interested in hearing from you, the Storyfix community, for your counsel on forthcoming content. Use the comments here, or email me directly, to suggest specific topics and focuses you’d like Art and I cover in the coming months. This is your tool, so please contribute your thinking to help us help you.

*****

A compendium of posts – mine – from Killzone.com

You may know that I’ve been posting to the Killzone.com for well over a year now. There is a diverse group of contributors there, including a couple of well-known authors you may have heard of, not the least of whom is my craft colleague in arms, James Scott Bell.

Click HERE for a sequential thread of these articles. It’s an entire book’s worth of content and perspective.

Next week I’ll be sharing, in full, another guest post I contributed recently to Writer Unboxed, which stirred things up a bit. Because, you see, on that site and on Killzone there are authors who ascribe to this approach to story development: “There is no right or wrong way to tell a story, unless you do it my way,” – their way, in this case – “in which case it is the right way.” One of them suggests writing cannot be taught (right after this assertion he refers you to his upcoming workshops), and another claims he can impart everything of value he’s ever been told onto one side of a 3 by 5 card, which is interesting.

Too bad they’re both full of complete and utter crap on those fronts. Because simply by putting it in print, some poor writer will believe it to be true.

Here at Storyfix, Art and I are committed to shining a light on principle-based story development, with a qualitative focus on what empowers stories, rather than what simply finishes them.

The post A Few Storyfix Updates appeared first on Storyfix.com.

August 26, 2017

“The Two Questions” — A Guest Post by Art Holcomb

More goodness from our friend Art, who is always worth the read. (I chip in an additional thought to open the Comments thread.)

The Two Questions

by Art Holcomb

I want to talk to you about a place where all writers get to – regardless of our form, genre or level of experience.

I’m talking about The Big Suck – that place where we have written ourselves into a corner.

Does this sound familiar?

You might have been cruising right along, hero making his/her way through the Special World of the story, fighting the bad guys, getting the girl (or the guy) along the way – basically plowing his/her way through the story and are well into the throes of Act 2…

When suddenly…

Nothing.

Nada.

Zilch.

You come up completely empty and slam into a creative wall.

Maybe your hero isn’t cooperating, or the villain is done something that you just don’t understand. Maybe you’ve crafted a threat that’s too overwhelming (or worse, isn’t powerful enough) or you’ve suddenly and quite simply run out of ideas.

Worst of all, maybe you’ve gone back and re-read what you’ve just written and realized…

It’s boring. It’s just plain-vanilla, cold-leftover oatmeal BORING.

And then the anger comes.

You suddenly hate the story. You begin to doubt your abilities and ask yourself why you started this foolishness in the first place.

Here’s the good news:

I‘ve been in this hole and I know the way out.

At this point, I want you to stop. Just Stop.

Understand that every writer goes through this. It’s part of the process and there’s no way around the problem.

All you can do is go through it.

The Two Questions

Here’s a technique I learned from one of my mentors and one of the smartest writers I’ve ever met, Steven Barnes ((learn more about him here).

First, take a moment to remind yourself where you are in your story. Reread the last passage. Really find a way to put yourself in the place of the character you’re writing about. Understand their situation. Feel the emotions that the character must be feeling at that very moment.

Now, ask yourself these two questions:

QUESTION #1: What is ABSOLUTE TRUTH about this moment?

What can you say here that is absolute, positively true about what’s happening?

Not what you think the reader wants to hear. Not what you believe would be interesting.

But what is true about what’s happening at this very moment.

This may take a while to understand. More than anything else, readers want authenticity from their storytellers. They are in your story at this moment with you so that you can evoke in them an emotion that they cannot get elsewhere. That emotion is best produced by the truth that you are subconsciously trying to tell them through your writing.

Spend a little free-writing time to explore the setting, the underlying motivation of the characters. How would YOU face this problem (this is key to the authentic moment because, in some subtle but important way, YOU are this character)? Try to sympathize with the antagonistic forces involved here.

That is – FEEL your way through the moment.

And then, move directly to . . .

QUESTION #2: What does this moment say about us AS A PEOPLE and about the HUMAN CONDITION? Regardless of whether you’re writing a science fiction or a mystery or a romantic comedy, every story tells the reader something about who we are as a people. What our lives are like and what we have to pass along to others.

Regardless of whether you’re writing a science fiction or a mystery or a romantic comedy, every story tells the reader something about who we are as a people. What our lives are like and what we have to pass along to others.

For example, romance stories feed our desire to be connected. Science fiction stories give us a sense of what we are becoming. Fantasies lead us down a path towards our own dreams and alternative realities.

Each story, whether we realize it or not, says something about us as a species.

The Purpose of Story

So, lean into that curve. Seek out the truth that you’re trying to tell.

You may just realize a deeper level of your own storytelling.

These two questions serve the original purpose of Story from the days of our ancestors. Stories were created by the elders of the village to instruct the young people about what their lives were going to be like. They needed to know what to look out for, to know where they came from and, more importantly, gain some inkling of an idea about where they were going.

For example, the Cave Paintings of Lascaux, France, warned of the danger and glories of the hunt. The tales told around the campfire were the lessons of the day, made all the more important by the power of the Storyteller. The emotions brought forth in the story bound the lessons into the mind of the listeners and they . . . learned.

That is the role of Story. And you, as the Storyteller, can find your way out of the corner by leaning into that curve and going for the deeper truth.

It’s the best way I know to write myself out of a hole.

It might just work for you, too.

Until next time – keep writing!

Art

P.S. – If you’ve enjoyed my posts here in StoryFix and are interested in learning more about our teachings about the craft of writing, drop me an email at aholcomb07@gmail.com and we’ll send you information on our seminars, workshops and boot camps.

The post “The Two Questions” — A Guest Post by Art Holcomb appeared first on Storyfix.com.

June 12, 2017

A Return to Hardcore Story Craft

Hey storyfixers… I know I’ve been MIA for an inexcusable length of time. Thanks to Art Holcomb for filling the void a few times while I went about the business of reinvention, rejuvenation, ducks-back-in-a-row stuff, and a general inventorying and understanding of why people read my work, why they come and then go away, and what writers are truly looking for when it comes to mentoring, teaching and the discovery of totally free information that will take them deeper into the craft of writing and the pursuit of their writing dream.

Art suggests that, perhaps, some Storyfix readers believe they’ve internalized all that I have to offer, and that the wagons are being circled here. Some believe – inaccurately – that the title of this blog, and of my latest book (

Some may believe – inaccurately – that the title of this blog, and of my latest book (Story Fix), imply I’m all about editing and rewriting, when in fact the most valuable thing to be found here is a perspective on what it takes to develop and implement a viable story from the square one comprised of a compelling premise (emphasis on the word viable, because not all ideas are worthy of a story… this being one of the most toxic misbeliefs floating around out there) using provable, universal and perhaps heretofore unclear (and therefore rarely or vaguely described within the general writing conversation) principles of storycraft.

Let me state the complex in a succinct way:

I believe in, teach, write about and can substantially prove the value in mission-driven, criteria-based story development. I’m betting you may not have heard the writing proposition framed quite that way… and I’m also betting than the notion of criteria – not a magic pill, but a strategic logic – already appeals to you. Especially if you’ve been at this a while.

Too many writing gurus preach benchmark-free story development. And yet, stories that work always – not almost always, but always – touch on specific benchmarks, structural and otherwise… so why aren’t we talking about and writing in context to them?

We’re going to continue a deeper dive into all of this.

If you seek an alternative to the vague frustrations of “writing what you feel, because there are no rules, damnit, so we can just write without thinking about it too much,” all without some sense of how to navigate the creative options along the path… if you seek that higher ground, you’ve come to the right place.

I’m certainly not the only “guru-type” selling you the truth (Art, for example, is spot-on with everything he says about storytelling; James Scott Bell, as well, among others… read us all, and soon you’ll notice the commonality, as well as the difference), but I may be the only one who has coined some specific labeling and modeling that makes it immediately accessible.

I’ll also shine a light on what’s risky, and what isn’t valid thinking.

Take the common advice, “just write,” for example.

“Just write” can, if taken in a less than fully-informed way, become the most toxic writing advice you’ll ever hear. Yet, if you can wrap your head around the core principles you’ll encounter here (including the over 700 posts that are available in the Archives; use the search function to find articles on virtually anything concerning the craft of storytelling), you’ll find a rich new context from which to write your stories. You’ll discover an informed context, rather than simply writing what you feel without an understanding of how that fits into a professional storytelling paradigm.

Those who succeed at the “just write” approach usually do so – and will defend that advice vehemently – precise because their core storytelling instinct is already informed by these principles. Even without knowing that’s what’s going on.

I read recently (in a Writers Digest article) that mega-author JoJo Moyes (11 million books sold, and counting) claims to not know how she did that, and that when she begins a new book she feels totally lost. That’s what I’m talking about… obviously, her instincts are keen and her ear highly developed… perhaps, as she claims, without even knowing how or why.

Better to know, I hope you’ll agree.

This is advanced stuff.

And yet, it is the very foundational bedrock of what the new writer needs to understand. It is, in that way, paradoxical in nature, because the advanced craft of writing is no more than a deeper understanding of what newer writers must encounter and grasp (even if only instinctually) before they can truly get far from the starting gate.

So that’s my ongoing platform: framing the most basic, hardcore criteria and nature of the elements and essences of storytelling in ways that will clarify and make them more accessible to both the new writer and the working writer going forward.

If anything has gained me a spot at the table when it comes to writing about writing, it is that I seek to cull out, summarize and present the elemental essences of a story – both in terms of parts and reading experience, in function and in form – in a way that resonates with many. Even – perhaps especially – after they’ve heard it from others, or in courses from names like James Patterson that are really, when you boil it all down, some form of “this is how I do it” shallow rehash of the obvious, without a real thinking-writer’s template for understanding what a story needs to be, regardless of how you get there.

Even the novels of the deniers demonstrate the very principles that I will show you. Everything I offer up has that end-game in mind: a story that works. Really works.

Without bloodletting, suffering or years of frustration over a massive pile of rewrites.

Do you really want to take years to get there, and then not truly understand how you did what you did? And then, how to do it again, even better?

Can you really do what Stephen King does, the way he does it and advises you do it, too? Have you bought into the myth of relying on under-informed instinct, when you have access to the learning that will turn on the light of a higher understanding?

If you know what you’re doing – and believe me, this is something that can be learned – you can nail your story in two drafts. Art preaches this, too, in case you need outside confirmation. The more you understand about story criteria, the more you’ll apply it to the stories you develop.

Almost always, when “famous novelist” writes about writing, they will be focusing on process – their process – rather than the criteria and fueling of the end-product. It’s like LeBron James talking about his training and diet, rather than the fundamentals of the game he plays. Like, how to play defense against Stephen Curry.

So what’s next here?

I’m developing a multi-part series on “Core Craft for the Emerging Novelist,” which exists within one of my new video modules, as well. Look for at least 14 posts in that series.

I am doing a deconstruction of the novel, “The Girl on a Train,” which illustrates how the principles become visible, and therefore, confirming your understanding of how and why those principles apply. Look for that soon, inserted within the multi-part series I just mentioned.

Until then, here’s some hardcore content for you to chew on… right now. This link will take you to a post I wrote for Brian Klem (October 2013), which first appeared on the Writers Digest website that he manages.

A little taste of what is possible when you hunger for more craft.

The post A Return to Hardcore Story Craft appeared first on Storyfix.com.

May 26, 2017

Part 2: What a Studio Executive Wants You to Know About Your Novel

A guest post from Art Holcomb

And so, back to our story . . .

When we had last left our hero (that’s me), I had just had lunch at the Paramount Studios commissary with a studio executive named David, who was kind enough to ask me back to his office bungalow to continue our conversation.

We had just settled in when David said, “Adapting novels into film is the lifeblood of what we do, and therein lies the problem.”

“How’s that?” I asked.

“Not every novel – including some best sellers – adapts well to the screen. Many fantastic stories, some with powerful depth and import, can never make it to this wider audience simply because of the way the story was told.”

“Okay,” I said. “So what kind of story does make for a great adaptation?”

David leaned back and looked out the window and frowned. “Well, I guess the first group of adaptable stories could be called THE CLASSICS.”

I grabbed my notebook and started writing.

“For example, one type of classic is the stories from the Bible. You know – Ben-Hur, David and Goliath, Noah and the Flood. Think Cain and Abel and you can see the universal appeal. They are all well-known, powerful tales; all have a tried-and-true structure and have that all-important built-in audience. In that way, fables and fairy tales fit into this category as well.”

“Right,” I said, writing furiously.

“And there’s always Shakespeare and all of its re-imaginings. Remember, West Side Story is really just a fabulous take on Romeo and Juliet. Shakespeare was a turning point in the stories of our Western culture. He gave us elemental stories with universally relatable emotions – forbidden love, envy, greed, longing, anguish. They’re the types of story that every member of every culture across the globe can relate to. The whole of human experience can be found in his work. And universal appeal means at least the possibility of a world-wide audience.”

And, of course, you have to include here the Other Classic – that is, anything that you read – or avoided reading – in high school. Gatsby, Huck Finn, Animal Farm, and the Scarlet Letter – like that. They’re well known, millions are at least familiar with the story, and so have that built-in audience. Attach a bankable star and you’re half way there.”

I was beginning to see where he was going.

“What nearly all these stories have in common,” David said, “is that they are in the public domain. These older stories mean that we don’t have to worry about acquiring their rights so we’re free to adapt them immediately, and that’s always attractive.”

“But the most valuable thing about these stories is that the writer and director can take the bones of these classic stories and put their individual twist on them. I still remember seeing Shakespeare’s Richard III, which was originally set in 15th Century England, re-imagined into a modern day Nazi Germany-like society. Very much the original story, but set in a completely different time and place. And it was fantastic! The same thing might be done with any public domain film.”

“That’s a lot of possibilities,” I said.

“Now – the second group: There are some novels that are so popular that they simply cannot be ignored. Books with such Gone Girl, Harry Potter, 50 Shades of Grey. They all have built-in audiences and massive followings. And there are so many readers who can actually see the book already playing out in their head that they can’t help wanting to see it on the big screen. They are a slam dunk for adaptation.”

I really needed him to slow down a bit. My hand was beginning to cramp.

“In this group, there are also what I call The Beauties – books that immediately spark the imagination. They have breathtaking images, historically powerful moments-in-time, sweeping space battles – they’re stories that immediately thrust us into their world. Movie stars are particularly are drawn to these projects because they can immediately see themselves as these heroes. And certain directors will see in the story a chance to really put their personal vision to work and make it their own. They can become the kind of films that can really make a career. These are the films with great story universes and locations that really come alive in the telling – where the world itself almost becomes one of the characters. Adaptations for these can be an easier sell.”

David paused and sat back in his chair and stared at me, waiting for me to draw the obvious connection.

“But. I said, “Should novelist even consider the possibility of an adaptation when they write? Aren’t novels about bringing the author’s unique vision to life? Shouldn’t they just tell their story THEIR way?”

David smiled. “Sure, and we need that, but we’re talking here about the WAY the story is presented more than the author’s vision for the story itself. Remember, a great story is a great story! Movies, books, TV – from our standpoint, these are all the FORMS in which you choose to tell that story. But you can choose to execute the novel is such a way that it naturally invites adaptation for the screen. Screenwriters do it all the time, as do studios. Do you believe that Disney only wanted a movie out of the Pirates of the Caribbean? That was inspired by a ride. And look where that has gone! And don’t you think that Michael Crichton had more than a film in mind when he wrote Jurassic Park – it’s now an entire land at Universal Studios.”

“Absolutely,” I said.

“What each of these things has in common is that they were all great STORIES first. Nothing can happen unless that happens first, and the novelist must first learn to be a great storyteller – anyone who doesn’t work hard to learn their craft will never really succeed. But the power of a great story is in how it captures the imagination, how it inspires others with its vision. If you can write a great story and present it in a way that arouses the creative talents in others, you have the possibility for your novel to do more than sell a couple of thousand books.”

I suddenly got what he was saying. This is the way that screenwriters think but novelists don’t. Every writer dreams of having their book made into a movie but so few have any idea how to make more likely. There are so many things you can do to make your story more attractive to filmmakers and improve your storytelling skills in the bargain. But no one teaches that.

David looked directly at me. “You can have the possibility to tell a story that could reach millions more people around the world than your novel alone ever could – just by the way you present it.”

“So,” I said, “How does a novelist do it?”

David leaned in. “Well, let’s start with the obvious,” and he ticked off a list on his fingertips.

“You need a novelist who understands not just writing but storytelling. A novelist can make a compelling read but it takes a great storyteller to make you feel and live the story enough to be start seeing the possibilities in the world they’ve created. Just think Star Trek and Star Wars. People are drawn to the world these writers have created – Hell, people want to LIVE in these worlds.”

“Second, many novelists write a story that, in the end, ONLY THEY are interested in. You have to write universally, with universally relatable issues.”

“Next, you need a very simple plotline with an easily understandable goal. In this type of story, someone wants just one thing. Or someone wants to get to some certain place to escape some specific fate. Most novels glance right over that, and write convoluted plots because they think that’s what good stories are made of. They’re not!”

“Then, you require a compelling, human hero. He or she has good points and flaws, strength and weaknesses. The audience has to be able to recognize something of themselves in the hero in order to make a real connection.”

“You need a powerful, clear and understandable obstacle, villain or antagonistic force. And the more your villain believes that they are the hero of your story, the better your story will be.”

“And you need life-and-death stakes. Understandable, palpable stakes.”

“You see,” David said, “Movies aren’t complex and so much of the problems in adapting most novels is that movies are all visual and so many novels aren’t.

David and I talked well past sunset. I had completely forgotten about my pitch session (luckily I was later forgiven) and, over the years, I had used what David and Bob taught me to teach a new group of screenwriters and novelists.

And now, it’s available to you.

I’ve gone on to use this information to create a new seminar we’re offering this year called Writing the Cinematic Novel.

In it, we cover:

How to find and exploit stories in the public domain (we include a great list of stories!)

How to think like a screenwriter and paint your story with a filmmaker’s brush

How to bring out the most evocative and cinematic images in your story

How to create characters who can thrive on the screen

And how to write great and powerful scenes

The on-line class starts later this summer and we have a special discount price for all of Larry’s loyal StoryFix readers who act right away.

If you’d like more information about this seminar or to find out more about our other classes and services, drop us a line at aholcomb07@gmail.com with the subject line ADAPTATION and we’ll send it out.

Remember, seats are limited and this special pricing in only good through June 15th.

Thanks for spending this time with me. Larry’s coming up shortly with his return post – it’s a great one.

So, until next time – Just Keep Writing.

The post Part 2: What a Studio Executive Wants You to Know About Your Novel appeared first on Storyfix.com.

May 13, 2017

What an Actor Wants You to Know About Your Novel — a guest post from Art Holcomb

Hi… it’s Art here. It’s my honor to be filling in for Larry here as he finishes up working on new training videos and other materials for you, his StoryFix family of writers. He’ll be back very soon.

In the meantime, I want to tell you a story about the unexpected power of your characters.

*******

Years ago, I was on the lot at Paramount Pictures in Hollywood for a story pitch session. And, as I was early, I decided to grab lunch at the commissary.

Now, the commissary was one of my favorite places in the world because I never knew whom I might see – actors and actresses, directors and studio execs.

For a young writer like me, this was like having all of Hollywood in one place.

I got my lunch and found a place at a table with a veteran actor (we’ll call him Bob) and a studio executive named David, both of whom I knew from my time pitching to Star Trek. As we ate, we talked about the business and politics and the world. Being a bit bold, I asked a question that had bothered me for some time.

“Bob,” I said, “I train writers – both screenwriters and novelists – and I’ve always wanted to know something. If you don’t mind my asking, what are your absolute favorite roles to play? The ones that absolutely draw you doing a particular script?”

It seemed to me to be the obvious question. Almost every novelist and certainly every screenwriter I had ever met had a burning desire to see their story turned into a movie and to hear their words spoken on the big screen – I know it had been a turning point in my own career. So, if I knew this, I could improve both my own work and the work of my students.

But the real question here was – how does one write a role that an actor really wants to play?

Bob thought about it a bit and said, “I guess I have three types of roles that make me want to do a picture.” He smiled and said, “And so, in the tradition of building suspense, I’ll give them to you in reverse order.”

And what he said next really surprised me.

“My Number Three choice would always be to play – The Hero.”

“Really”, I said. “Number Three?”

“Absolutely!” he said through a mouth full of salad. “In a well-written piece, the hero is the most powerful role. He or she should get all the great lines and the powerful scenes and gets most of the publicity. A movie is made up of perhaps sixty separate two- minute scenes, and it was Jack Nicholson who once said that he would consider playing any role that had for him three good scenes and one great one. Plus, when you’re playing the hero, the story is all about your journey, the focus is on you, so what’s not to like? If it’s good enough for Jack . . .”

Made sense, I thought.

“So, yeah, absolutely,” Bob said. “But, really, the Hero’s not even the best role.”

“Okay,” I said. “What’s Number Two?”

“The second best role to play is always – The Villain. The villain is where so much of the power and personality comes through. The range for most heroes is limited because of what they must stand for, but a villain can run the gamut. If for no other reason than the way the audience comes to hate a great villain, most great movies succeed or fail based on the power of the villain and, besides, they are always such a gas to play.”

By this time, I was a bit lost. Besides the hero and the villains, what other great roles were left?

Bob leaned back in his chair and smile wistfully. “But the absolute best role is the one that we are all trained to play, they one that gives us all a chance to show the audience exactly what we can do as actors . . .”

He paused for effect.

“I will always be attracted – first and foremost – to play any character who really suffers in the story.”

“Why?”

“Most people would say that we come to the movies or read a story or watch a play to enjoy the plot of the story. And we have always believed that plot is what draws us to the film. But the plot, from an actor’s standpoint, is only there to show the world the nature and range of human emotion through the actor’s art. Great stories, whether in films, television, or novels, are first and foremost about the truth of the human struggle.”

“I agree,” David the studio executive said. “Consider any film that you’ve really loved. If you think about it, you were really drawn to the emotions that the characters portrayed – the pain, sorrow, anguish, elation and sheer love and happiness that you were able to connect with. It’s through that emotion that the audience bonds with that actor. Well-written pieces which always show that kind of human drama – the length and breadth of human emotion – and, it’s what makes the story a hit or a flop. From a pure craft standpoint, I would much rather play a powerful role is smaller film than the lead in a blockbuster. Fame, as wonderful as it can be, is not why most of us became actors. Humans, playing roles where the human heart stands in real conflict with itself, where pain and suffering can be shown honestly, makes that role – and that actor – unforgettable.”

I was beginning to see Bob’s craft – and my own work – in a new light.

Bob stood and gathered his belonging. “And the worst part,” he said as he got ready to leave, “is that there are VERY FEW of those roles that come an actor’s way in his or her lifetime. And since the majority of movies are adaptation of novels and other materials these days, the problem lies as much with the sort of characters in novels today as they are in screenplays.

And, with that, Bob was gone, disappearing into the rush of people hurrying to get their lunch before the commissary closed for the day.

David said, “I love that guy,” and we sat silent for a while as I considered it all.

Writing for emotional impact was something I taught but had never considered from Bob’s position. Stories are, in the end, emotion delivery systems. We all come to the movies and to novels to be taken out of ourselves, to be made to feel things that we might not feel in our own lives. So the vehicle for these feelings had to be based in universally relatable emotions. We watch films and read novels for the same reason that our ancestors sat around the fire and talked about that day’s hunt. Stories were created by the elders of the village to teach the young people of the village about what their lives would be like and how to cope with the challenges ahead. All good stories invoke real emotions in the audience, and it’s that emotion that binds the stories to us and us to the stories.

Novelist or screenwriter, if a writer cannot write with emotional impact, s/he will never really reach the audience.

It was something I’d never forget.

I turned back to David as he was finishing his lunch.

“So when’s your pitch?” he asked.

“In about an hour.”

“I’ve got some time,” he said as he got up to leave. “Walk with me back to my office. Bob really only gave you part of the story.”

And so, fascinated (and not believing my luck), I followed him out.

NEXT TIME ON STORYFIX: What Hollywood wants you to know about your next novel.

*****************************

A special offer to STORYFIX readers: We have a new slate of seminars in 2017. We’ll be teaching you about How to Write for Emotional Impact as well as How to build your Writer’s Platform and Brand for ZERO DOLLARS . . . . PLUS news about our Summer Boot Camp that can get you up, writing, and possibly published within the next three months.

If you’re interested in these and any other of our courses and seminars, just drop me an email at aholcomb07@gmail.com, tell me you’re a StoryFix fan, and we’ll let you know about exclusive discounts we’ve created just for Larry’s loyal readers.

*****************************

Thanks for spending this time with me. Larry will be back soon.

So, until next time – Keep Writing!

Art

The post What an Actor Wants You to Know About Your Novel — a guest post from Art Holcomb appeared first on Storyfix.com.

March 1, 2017

The Bermuda Triangle of Storytelling

The goal of today’s post is nothing less than to explain why writing a novel that works is hard.

As opposed to, say, a pile of 50K-plus words poured into a steaming pile during, say, the most recent month of November, that doesn’t.

But if you break it down, there really aren’t that many different things going on, categorically. And with so many of us trying to do it, and so few of us producing a sure thing (this isn’t a knock on the new or struggling writer; so many famous names and titles were rejected multiple times before finding a place in the market, and so many others have one flash of the spotlight and then virtually disappear), why are the odds so long?

Especially since there are more than a few folks like me seeking to clear the air and impart some sense of what works and what may be holding you back.

In an effort to get to that bottom line, I set out to view the problem differently.

To break down what actually happens in the moment of collision between a writer’s intention and action, tempered by the heat-resistant presence of that author’s distilled sense of story.

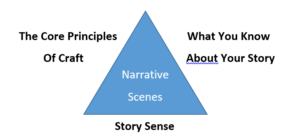

In the end it all boils down to three things, and really, only three things.

What we know about storytelling (the sum of what we think we know and actually do know about how a story is built – craft – and what it is built of);

What we know about the story itself, including the ending (which explains why some drafts work and others don’t);

and, then, how we steer that ship across the void of the blank page (our story and prose sensibilities).

That last one is the kicker. It explains (or it doesn’t; more accurately, this is just the label on a map about a place we know very little about, sort of like the Marianas Trench of storytelling) why some writers are consistently better and faster than others… writers who seem to wield a natural gift of some kind.

Versus those that think they do. Finally realizing that you may not yet be among that tiny crowd can, for some, be the most empowering moment in your writing journey.

Because that might be when you let craft into your process.

Welcome to The Bermuda Triangle of storytelling.

Because in the stormy, uncharted confluence of these three natural forces of storytelling, some writers get lost and some are never heard from again.

Two out of three of these sub-processes may be good enough… if you have the time or patience for it. But nailing the story reasonably early (for many this means, in this lifetime), and easily (before your world collapses, or before you begin deceiving yourself about it)… that requires firing on all three of these cylinders.

All three of these forces, though — 1) knowledge of craft… 2) a vision for the story… 3) a sense of how to get it on paper — are in the end required, at least in some perhaps unequal proportion. The good news is that each time we give it a try, we make a deposit into the each of these three creative/intellectual accounts.

Soak up enough craft, apply it to your vision for the story, and your story sense is bound to elevate. Do this long enough, in context to the principles of craft, and your story sense will at some point catch up with your enthusiasm.

Analogies abound. I’ll spare you those for now, but let it be said, immense knowledge without some sense of magic and movement does not a singer or dancer or artist make.

The reason we study craft IS to beef up our story sense. To skip the craft in reliance to one’s natural storytelling gifts is like preparing for the Olympic trials without training… because you were born fast and strong.

Clearly, this isn’t math.

It’s more like Olympic figure skating or platform diving, where results and the pursuit of perfection are determined by a bunch of imperfect human beings levying judgment. But even the experts often get it wrong (Kathryn Stockett’s The Help, for example, was rejected by 46 agents before one of them had a higher sensibility to the party), thus testifying to the imprecision of story sense.

This little model gives us something to work on and build upon.

Not to mention, something to blame.

From the moment the spark of a story idea lights up our brain, continuing through the entire process up to the moment we set the story free (which is to finish it and move on to something else, whatever that looks like for you), we are juggling these three very different intellectual and creative phenomena. Viewed separately, we can see how they apply (if you can’t, it is a sign that one or more is still underdeveloped). But it is in the areas of overlap where the math becomes vague, where so many have tried to credit an unexplained inspiration or what becomes the equivalent of a muse, or perhaps just plain blind luck, good, bad or otherwise.

In the absence of this understanding, that may be as good an explanation as any.

The principles are always available to tutor your story sense.

You don’t need a “natural storytelling gift” (as some claim) to develop a novel that works, or become a successful career writer.

That’s why Jeffrey Deaver proudly says he writes twenty-two drafts of his novels… which, at a glance, is not the outcome of a highly developed story sense. Rather, that’s Deaver trying to get it right, over and over and over again. He succeeds because he follows proven, reliable, solid principles of craft – he has the requisite knowledge about how and why stories work – and doesn’t settle until he knows as much about his story, from premise through the entire structure, as he needs to for it all to work… and to recognize when he gets to that point.

Novels that fail or under-perform are often simply drafts that the writer didn’t – perhaps cannot – recognize as unfinished. Which is a story sense issue every time (lack thereof, in this example), arising from an inadequate foundation of story knowledge.

Bottom line: you may have been born with The Gift. But most writers who truly hold, nurture and present a solid sense of story, got there as a product of craft, leading them to a vivid vision for their stories.

This is precisely why experienced authors don’t write every idea that pops into their head. They have the story sense – born of craft – to recognize a rich premise and not jump at one that is merely clever.

Story sense is what happens when you lead with craft, rather than relying solely on your gut.

That can work… usually for Stephen King and authors like him. Which means we must ask if we consider ourselves in his league.

*****

If you haven’t checked out my first wave of craft training videos, with a slant toward newer writers, click HERE. Remember, as a Storyfix.com reader you get a 25 percent discount… just use this code – storyfix25off – during the Vimeo checkout process (the Download links on my new training website take you to the Vimeo page where the videos are available).

A new wave of training videos will be launched in March 2017.

The post The Bermuda Triangle of Storytelling appeared first on Storyfix.com.

February 2, 2017

The #1 Challenge Facing Writers Today

It’s not what you think it is.

And you’re already a part of it.

Art Holcomb and I — you know Art if you been here a while; if not, Art is one of the foremost writing mentors and lecturers in the country — recently made a 30-minute audio recording, a teleseminar, really, that ended up focusing on this important topic.

Important, because it can sabotage everything about your writing dream, including your learning curve… without you even knowing it.

Writers are deluged with information. Some of it is obvious. Some of it is gold.

Too much of it is less than credible, and sometimes it is downright toxic.

So when Art asked me this question in the audio interview, I ran with it.

I am passionate about writers understanding the truth about what we do, how we do it, and the liberating, mind-blowing awareness that suffering is optional.

The purpose of the recording was to introduce my new video training products to his significant following and readership. So there’s that, alongside the observations of two guys who are among all the noise out there, screaming our lungs out.

You can listen to it HERE.

*****

Another listening opportunity...

Last April I had the honor of presenting the Keynote address at the Las Vegas Writers Conference, after doing two workshops during the conference. It was 74-minutes of gut- wrenching vulnerability, with harrowing tales from the writing road that made the audience wince, laugh and generally realize that I am not the grizzly bear middle linebacker of a writing guru-type that I am reputed to be.

Despite looking exactly like that in the video.

I just posted this on my new Youtube channel, if you have some time. It was shot from the audience, so it’s a little raw… as any worthwhile keynote should be.

Check it out HERE.

*****

The Roller Coaster Ride of Writing Professionally

You write, you publish. Then you get reviewed.

You get praised, and you get blasted.

The thing that has amazed me is the vehement vitriol that some reviewers inject into their reviews. Don’t like my novels? Don’t get my approach to writing, because it isn’t quite like what you heard from Famous A-List Author at your last writing conference? Don’t like my analogies and my lists of criteria? Don’t like all the “big words” I use to preach the gospel of craft? (You’d be surprised at how often this appears in reviews… words like “Epiphany” and “story essence” and “thematic resonance” and “dramatic tension” seem to challenge and confound some folks… which to me is like the term “load bearing” fogging the brain of an aspiring engineer; if the language of the craft confuses you — it’s not my language, by the way, it’s the language of the avocation — what are you doing reading a book intended for writers who aspire to write professionally in the first place?)

Last night I made the mistake of going onto Goodreads to see what some of the folks out there were saying about my work. The novels and the writing books.

Big mistake.

Believe me when I say, as gratifying as some of the positive feedback is, the enthusiastic blasters suck up all of one’s attention — let’s just say my evening was emotionally compromised — leaving you wondering what you did to offend or confuse those who didn’t seem to get what so many others were appreciating?

Comes with the territory. That’s the learning here. Not everyone gets you., and not everyone gets it.

There is always a lowest common denominator in any reader demographic — in the real world they are confused by four-way stops and ATMs and still believe in characters that talk to you from the page, telling you what to write next — just as there is often some real validity in the criticism that resides within one, two and three-star reviews, not all of whom are haters.

Today was better. This review showed up on Amazon for my latest writing book (Story Fix: Transform Your Novel from Broken to Brilliant), and it helped me put it all back into a healthier perspective.

Give it a read HERE.

*****

If you’d like to check out my new training videos — there are five of them now, with more on the way — click HERE or HERE (this one is my new site for these virtual classroom video modules).

And if you’d be interested in hearing more about a new weekly Advanced Training Shots for Serious Authors — short videos with bluetooth-able audio (5 to 10 minutes, delivered to your Inbox every Monday morning), offering high-level learning and insight that applies to the application of the core principles, rather than an introductory context for them — drop me a quick email and I’ll add you to that rollout list.

Thanks for listening and reading. I really do appreciate you.

Larry

The post The #1 Challenge Facing Writers Today appeared first on Storyfix.com.

January 23, 2017

The Bottom-line Explanation of the Mass Failure of Authors

In the omnipresent kumbayah of the writing community, it is considered impolite, if not impolitic, to utter this truth aloud: most stories fail. Most writers fail.

That has been true since the advent of selling stories for money, and it remains true today, even in a world in which anybody can publish anything simply by pushing a button.

There is a reason—an over-arching, infallible, contextual reason—that tees up a set of powerful, more visible explanations stemming from it.

It is this: more often than not, new writers don’t know what they don’t know.

Some new writers don’t even understand the nuance and depth of what that actually means.

Storytelling, much like walking, seems natural and organic. But while that is perhaps true on the story-consumption side, it doesn’t mean we can all be professional dancers or Olympic runners without learning a thing or two.

They are shocked when told that their novel—usually their first, but unless they figure things out soon, this becomes a foreshadowing of the future—doesn’t conform to the shape and flow and expectations of novels in that genre, followed shortly by outrage that there even are expectations that create a narrative shape and flow that result in dramatic and emotional resonance.

They have misunderstood the axiom that says “there are no rules,” skipping over the part that says, “but there are principles involved.”

That, by the way—the shape and the flow and the expectations—are precisely why newer writers need to hang on to their student card. Because like it or not, like gravity and taxes and the outcome of certain elections, they just are. They’re out there, waiting to make or break your writing dream.

From my perspective as someone who teaches the craft of fiction in addition to plying the trade, the real problem is that this blank page mentality seems to have been legitimized within certain segments of the collective writing conversation. As if there is nothing to know, beyond one’s innate, genetic gift of story sense. As if first drafts will always suck, even if you’ve been writing them for three decades.

As if suffering is not optional.

You may have heard this myth promulgated at a writing conference keynote, for example, by a bestselling author—any number of them, in fact, because this is symptomatic—who, other than the investment of years and gallons of tears and alcohol, cannot come close to explaining how or why their latest book sold four million copies.

New writers in the audience tend to hear that number… four million copies… without hearing the inherent disconnect within the message itself.

Sure enough. Write just like Stephen King. If you can. But it helps to know what Stephen King knows, even if he rarely puts that in a box to share with the rest of us.

This is perhaps the number one, most prevalent explanation behind why writing is hard, why the percentage of wins is low, and why some writers struggle for years without getting it.

Because they don’t know what they don’t know.

Here’s a true story, one that is all-too common.

The story of a writer who didn’t know what he didn’t know. And then, when confronted by the The Truth, he wasn’t sure he wanted to buy into it.

At a writing conference a few years ago I was working the “blue page” desk, where writers dropped in for fifteen-minute consultations, five pages of manuscript in hand. Now, there’s not much that can be learned from five pages, beyond a first-hit assessment of the writing itself, and perhaps, how that one chosen scene plays.

One guy, very serious and confident—a bit of swagger, in fact—brought me his spy story. Before reading his pages I asked him to pitch the dramatic arc, resulting in a curious look. Because dramatic arc, at least as a common term, was one of the things he didn’t know that he didn’t know.

But that he needed to know.

It was an espionage story set in Paris. A retired US spy, formerly stationed there, is called back into service because chatter on the “dark net” has exposed a terror plot involving some bad actors (spy lingo for bad guy) that our hero used to interface with. His assignment would be to infiltrate and expose the terrorists and prevent the bombing.

Which, it occurred to me as I listened, is certainly something a reader would root for, and seems to be the raw grist of significant dramatic tension and a series of surprising twists. So far so good.

I asked him at what point in the story the hero—who had been shown being reactivated, shutting down his real life in the US before leaving, then setting up in Paris as he reintegrated with his former network—actually learn anything that required him to react. To move forward. Discover something. Encounter the unexpected. Or run into something that changed the game and made it all dark and risky and urgent.

He just stared at me, motionless. It was as if Rod Serling had hit the pause button.

“What I’m asking,” I said, “tell me at what point in the story your first plot point comes in?”

His eyes fogged again, so I attempted to clarify: “The key inciting incident. The doorway of no return, the launch of the core dramatic plot after all the setup has been put into play.”

Then his face suddenly lit up like an amnesiac being told he is actually a millionaire.

“Oh, that. It happens on page two-twenty, when someone he thought was an asset tries to kill him.”

“I see. As in, two-hundred-and-twenty?”

“Thereabouts.”

“How long is the manuscript?”

“Four hundred thirty-eight pages,” he said. “Thereabouts.”

We locked eyes. Time froze, the angels wept.

“So you’re saying that you have two hundred nineteen pages of setup in a four hundred thirty-eight page novel… yes?”

A beat. “Setup?” he inquired.

Deep breath. “Tell me what you wrote about for two hundred and twenty pages, prior to actually putting your dramatic arc into play. What happens over that span of pages?”

There was that term again. Dramatic arc. My bad.

Then he smiled. Sort of. Already sure his answer was the prize winner. It was, but not in the way he thought.

“You know,” he said, “the backstory, all about his life as an insurance salesman after his spy career, how he was restless… and there was his marriage breaking up, and his kid flunking out of Stanford…”

I jumped in: “For two hundred and nineteen pages? That’s what the narrative was?”

His smile began to wane.

“Have you ever heard the term, first plot point?”

He hadn’t.

“Key inciting incident?”

Head still shaking.

“Dramatic arc?”

Nothin’.

“Any notion about story structure, the three-act paradigm, the four-part story arc, the contextual flow of the narrative, leading to and then launching the dramatic arc, with at least two primary shifts spaced evenly over the body of the story to escalate tension and create pace?”

Crickets.

I summoned my best smile and delivered my softest introduction to the presence of certain principles that apply to, and are evident within, nearly every modern commercial story, truths that enlightened, trained writers not only know, but understand and practice, including the names you read and admire and wish you could become someday.

Then I recommended a few books, mine included, that might help.

“Sounds like a formula to me,” he said as he got to his feet. Because somebody out there, maybe in a keynote address, had used the word formula in a judgmental, erroneous context.

“That’s just a word. Is gravity a formula? It just is. Same with the principles of solid storytelling. It’s physics. Literary physics. They just are.”

He shook my hand, almost as if he felt sorry for me.

“I’ll think about it,” he said.

And off he went, about to pitch his novel with the fifty-percent-plus setup act to some agents, who would probably like the pitch, and just possibly, never even ask about how the story is presented.

They’ll ask for the pages, then five months later they’ll send him a rejection slip, without the slightest explanation beyond this being “at the present time, not what we’re looking for.”

And he will have learned nothing.

And thus the writing treadmill goes round and round.

We get to choose. Do we listen to the more informed voices in the writing conversation, or the ones that allow us to hide?

Or do we just run?

*****

Breaking news: Story Engineering (2011, Writers Digest Books), was recently named by Signature-reads.com to the #3 position in their list of “The 27 Best Books On Writing.”

If you’re hungry for further training on craft, please consider my new training videos (five so far, with more titles coming very soon), which you can see on my new training website and through Vimeo .

Also, Storyfix readers receive a 25 percent DISCOUNT off the list price for these modules. Use the code – storyfix25off – during the check out sequence to implement this discount.

You can join the mailing list HERE for new topic announcements and other news and special content.

The post The Bottom-line Explanation of the Mass Failure of Authors appeared first on Storyfix.com.

January 13, 2017

Case Study: The Untapped Dramatic Potential of Concept…

The traps that would compromise or even sabotage our best story intentions are everywhere.

Even when it all begins with a strong conceptual proposition… which is what’s up with today’s case study.

The author has consented to sharing this story overview here—via answers to the recent (and now shelved, with a replacement version coming soon) Quick Hit Concept/Premise Questionnaire. This is a generous consent, one thattakes great courage. My hope is that you might weigh-in alongside my feedback so that this author might have even more to consider.

Notice how the premise really states a situation, without ever really defining a hero’s challenge and path and goal, which in a good story becomes the core dramatic question explored along a core dramatic arc.

Notice how the weight of the themes tend to overwhelm (this often happens when theme is the initial inspiration), isolating the circumstance (which contributes to the setup) from expository conflict arising from dramatic tension, which in a solid story is what elicits an empathetic response and emotional resonance from the reader.

Rather, in this story the reader ends upobserving, rather than rooting, because there is little to root for.

Notice, in the final answers, how the whole thing changes lanes and becomes about something else entirely (a killer of stories), or at least seems as clear in the setup of a narrative as it is completely void of a third act (parts 3 and 4 of the four-part structure model), thus leaving us without an actionable story plan.

As an organic/pantsing, free-writing exercise… maybe this would work itself out. But as a story plan, it is only half there, and even then, is problematic.

After reading the author’s statement of concept, take a moment and ask yourself what story you might cull from that proposition, and where that inspiration might take you.

This is a study in story sense that is unfocused and unsure, without ever reaching a cohesive destination.

All of it fixable, but only with a clear hero’s quest—one with a more empathetic and rootable vision—in mind

My comments are in red.

*****

The title and genre of your story:

As Grey as Black and White / YA Historical

I like the title, its twisty (if not slighted twisted, as well, by inference)

What is the CONCEPT of your story?

What if a kid looked white, grew up thinking he was white, and later found out he was black?” What would happen? How would he feel? How would his ideas of identity change? His view of race in general?”

Nice, especially in terms of one of the criteria for a strong concept: the notion that several stories—even many different stories—could be written from this singular conceptual idea or propostion.

There are other criteria that apply as well, and this one works particularly well relative to the potential for dramatic tension, and the creation of an “arena” (racial tensions, in this case).

Of course, we still need a premise that works, but this is a good start.

Restate your concept using a “WHAT IF…?” proposition:

What if a blue-eyed, blonde-haired boy discovers he is black in 1960s Alabama?