Larry Brooks's Blog, page 5

August 29, 2019

When Knowledge is Misinterpreted as “Formula”

It happens all the time, often from the mouths of otherwise credible sources.

There is irony to it, as well, since the quickly dashed label of “formula” becomes, by definition, formulaic in its own right. It is too often the default go-to from someone who doesn’t understand the principles involved.

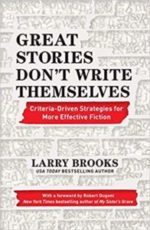

The following is a short excerpt on this topic from my new book, Great Stories Don’t Tell Themselves: Criteria-Driven Strategies for More Effective Fiction, that begins to unpack this commonly heard morsel of naivete. (I’ve broken this down into shorter blog-worthy paragraphs, because that, too, is the formula within blogs versus books… because best practices show us that this is what works best here.)

The short answer is that, within the genres, formula, by any other name, actually works. And if you don’t know the recipe for your genre, you may be in for a long haul process of getting to it.

****

(From the Introduction)

Consider the best dish you’ve ever eaten. Somewhere there’s a recipe for it, even when you or your favorite chef can whip it up straight out of your head.

When that recipe varies, the dish nonetheless turns out wonderfully because you know where it needs to end up. But if it varies too much, will it still be that dish? Maybe not; it may be inedible. If not for you, then for some.

So is a proven, delicious recipe a formula? And if you believe that it is, or even if you don’t, does that word even matter? The dish works because there is an accepted identification of requisite ingredients, proportions, and preparation that lead to a successful outcome. All of it somewhat flexible, because “season to taste” remains an open invitation. But there are also standards and expectations that tell us not to pour a pound of cayenne pepper into a wedding cake.

Formula is a word for cynics and the uninitiated, often applied to an uninformed perspective on story structure. It is an overly simplistic view in an avocation that is anything but simple. Craft is the better word to apply.

Craft is the practice of putting knowledge to work within an artful nuance of creativity and within a framework of expectation, standards, and best practices. At the professional level, when your intention is to publish, craft becomes essential.

****

Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves will be published on October 8, from Writers Digest Books (now a division of Penguin Random House). It is available for preorder on Amazon and BN.com.

The post When Knowledge is Misinterpreted as “Formula” appeared first on Storyfix.com.

August 11, 2019

How to Effectively “Tell” Emotions in Fiction

(C.S. Lakin is an A-list story coach, writing blogger and an award-winning novelist. Her name is synonymous with deep craft, which is exactly what she delivers here.)

(C.S. Lakin is an A-list story coach, writing blogger and an award-winning novelist. Her name is synonymous with deep craft, which is exactly what she delivers here.)

Many amateur writers ineffectively tell or name what a character’s emotions are. That’s often because they haven’t learned masterful ways to get the emotion across.

Telling an emotion doesn’t make readers feel or experience the emotion. It often creates more problems: the writing gets burdened with lists of emotions, and in the writer’s attempt to push harder in the hope of conveying emotion, she overdoes it. Adding to that, she might throw in all those body sensations for good measure, cramming the prose with so much “emotion” that the only thing readers feel is irritation.

Yet, there may be times when telling emotion is masterfully done. You can find plenty of excellent novels in which characters name the emotions they’re feeling.

It Has to Be in Character

Think about your character. Yours might be the type to name her emotions. With a young character, for example, it’s wholly believable for her to think in simple labels, rather than in nuance and complexity of emotion. What she is feeling might be complex, and the reader would pick that up, but what she herself believes, how she interprets what she is feeling, might be told plainly as it is understood plainly.

If it’s in character for your character to think like that, then, by all means, do so.

What kind of character would name her emotion?

One that has enough self-awareness to be able to identify what she is feeling. Or at least try to identify. Or want to identify her emotion.

Not everyone is like that. A teen girl is more apt to ponder her emotions than a middle-aged highly educated male computer programmer.

Or not.

See, don’t default to assumptions and stereotypes. It’s all about personality. Maybe your computer geek is deeply in touch with what he calls his female side. Or maybe, conversely, he’s quick to jump to conclusions, and that includes defining his and others’ emotions by labeling without much thought.

Let’s take a look at the award-winning women’s fiction novel Words by Ginny Yttrup. Yttrup’s character, Sierra, understands her emotions. She is self-aware and notices when she is feeling something. This fits her character, who is an artist who’s been through much grief and loss (I’ll put in boldface where she identifies her emotion).

By the time I leave Ruby’s, it’s almost eleven, and the sun is high overhead. I unzip the canvas top from my Jeep, and Van and I take off with the wind in our hair—or fur. I head out Mt. Hermon Road toward Hwy 17 with the intent of returning home to work for the remainder of the day. But as I tick off the miles toward home, something nags at me—a distinct feeling that I’m going the wrong way.

The closer I get to home, the more agitated I become. By the time Hwy 17 turns into Ocean Street, my agitation has turned to anger. I pull off the street and into an empty parking lot.

“What? What do You want from me?”

Van cocks an ear and then sinks down in the passenger seat.

I reach over and pat his neck, “Sorry, boy, I’m not yelling at you.” I sigh, “I just . . . I just don’t know what to do.”

I rest my head on the steering wheel and try to figure out what to do. Should I go back and try to find the little girl again? No. That’s ridiculous. This has nothing to do with me . . .

What if it were Annie?

The question pricks my conscience and then stabs my heart.

“But it’s not Annie!” I scream. “She’s gone. She’s”—the word catches in my throat and I feel hot tears brimming—”dead.” I wipe away my tears with my fist and then bang my fist on the steering wheel.

“She’s dead and this has nothing to do with her or with me!” With that, I put the Jeep back in gear and pull back onto Ocean Street. Within minutes, I’m in my driveway and out of the Jeep.

I hold the driver’s side door open for Van. “Come on, get out.”

Van doesn’t move.

“Van, come on!” He still doesn’t move. I reach behind the front seat for Van’s leash and attach it to his collar.

“Van Gogh, come!” I speak the command in my firmest tone and tug on the leash. He resists and remains in the passenger seat.

I throw down my end of the leash and walk around the car and open the passenger door. “Van,” I say through clenched teeth, “get out now.”

Van jumps from his seat to the ground, runs around the front of the Jeep with his leash dragging behind him, and jumps back in the driver’s side door. He maneuvers over the gearshift and sits back in the passenger seat.

“Fine. Stay there!” I slam the passenger door and head for the bungalow. Again I feel hot tears slide down my cheeks. This time I don’t even bother wiping them away. I reach the front door, turn the knob, and remember my house key is in my backpack, which, of course, is still in the car.

I turn back toward the car and see through a blur of tears that Van is still holding his vigil in the front seat.

“And she thinks you’re ‘progress’? You’re just a pain in the neck!”

As I again reach behind the front seat, this time for my backpack, Van leans in and begins licking the tears from my face. “Stop it.” I push him away. But he moves closer, this time resting his wet muzzle on my shoulder.

It’s too much.

Twelve years’ worth of pain rumbles to the surface. There’s no stopping it. Like a train roaring through a tunnel, the sobs come with a force I can’t stop—great heaving sobs. I hold Van tight and soak his fur. I don’t care what I look like standing in my driveway, clinging to the dog in my car. I don’t care about anything except this pain I’ve held for so long.

And can hold no longer.

I don’t know how long I stand there—minutes? Hours? Finally the sobs wane. I climb into the passenger seat with Van and pull a few crumpled napkins from the glove compartment. I blow my nose and lean into Van again, resting my head on him and closing my eyes. Spent. Exhausted. But oddly at peace.

The question comes again: What if it were Annie?

I think of my daughter so long gone from me. I think of the dreams I had for us. I wonder, as I have a thousand times before, what she’d look like now if she were still alive. And then I remember the fear I saw in the eyes of the child in the clearing.

Yes. What if it was Annie and no one came to help her?

I get out of the Jeep and walk back to the driver’s side and get in.

“Okay, you win. We’re going back.” I’m not sure if I’m speaking to God or Van—they’re seemingly working together. But Van’s tail wags in response.

As I turn the key in the ignition, I realize I’m taking my first step of faith in over a dozen years. I’m not in control here.

And I’m scared to death.

In this powerful scene, we see that wonderful combination of showing emotion, telling emotion, and thoughts that reveal emotion (the three ways to convey emotion in characters).

Don’t Try to Name the Complex Emotions

Sierra easily identifies the obvious surface emotions: anger, fear. But her moral dilemma, her inner conflict over this girl she’s seen in the woods who triggers memories of her daughter Annie’s death, sparks complex emotions. Those she doesn’t name.

Instead, it’s her thoughts of Annie, of her loss, that show readers what causes the emotions she then indicates via body language. Thoughts lead to emotions, in both our characters and in our readers.

Use Anger to Good Advantage

Anger is an easy emotion to grab when we don’t want to face painful emotions: loss, pain, shame, guilt, grief, or hurt. But anger usually masks something else.

To many people, hurt sparks anger so it looks like anger. But anger is the result, not the root.

A character might tell the emotion she is feeling—anger—but the reader knows it’s not really anger she’s feeling. Her body sensations and behavior may say “anger,” because anger is on the surface and moving her.

This is why complex emotions are best revealed by thoughts. If readers know the source of the emotions, the why, then they can empathize with the situation, and what they feel, by placing themselves in that situation, will be those complex emotions that you do not name.

It Has to Be in POV

If we keep in mind that the narrative—all the narrative—in a scene is the POV character’s thoughts, it will be clearer to us when to tell emotion.

When would your character think to name an emotion? When she is aware of her feelings, right? In the kind of moment when the character would stop and consider how she’s feeling. And only if it fits the character.

For example, when a writer tells the reader via author intrusion that his character is jealous, it’s one step removed. It’s out of POV.

Jason stood at the corner and saw his girl flirting with Bill Jones in front of the bank. He was jealous because he really didn’t know if Rose’s affections were genuine or if she was just toying with him and he couldn’t bear the thought that she might like that jerk more than him.

We sense immediately that this is the author speaking to the reader. Jason isn’t thinking “I’m jealous because I really don’t know if Rose’s affections toward me are genuine.” Right?

One great way to check to see if your narrative is authentic when writing in third person is to switch it to first. So, here, first off, ask: Is Jason the type of guy to stop and explore his feelings—while he’s standing on a corner reacting to this unexpected scenario?

Not likely, even if he’s set up to be a touchy-feely kind of guy. Not even if he’s a therapist. Not in that moment when he is reacting. Maybe later when he’s processing he’ll admit to himself that he was jealous. And he might name the emotion. It could be in dialogue, for instance:

“What’s bugging you, bro?” Steve asked him.

“I saw Rose talking to that creep Jones,” Jason said.

Steve eyed him, and a smirk rose on his face. “Don’t tell me you’re jealous.”

“Sure I’m jealous. She just agreed to go to Vegas with me. You’d be jealous too, if Cindy was making eyes at a loser like Jones.”

In that kind of situation, it’s believable that Jason is going to name his emotion. And it would work as internal dialogue or narrative too:

Jason stormed off down the street and into the nearby coffee shop. He blew out a breath, feeling like he was about to blow a fuse. Admit it—you’re jealous. You just can’t trust her. And that’s your problem. It’s always been your problem.

Which is basically the same as

Jason stormed off down the street and into the nearby coffee shop. He blew out a breath, feeling like he was about to blow a fuse. He was jealous. No denying it. He thought he was past that, had gotten a handle on the jealousy after Denise dumped him. But here it was, like some ugly monster from the Black Lagoon slithering up his neck, whispering poisonous words into his ear.

That’s a bit melodramatic, but I hope you get the point. It’s all about how your character would think.

When you tell emotions in fiction in a masterful way, it can be effective, believable, and powerful.

****

Want to learn how to become a masterful wielder of emotion in your fiction? Enroll in Lakin’s new online video course, Emotional Mastery for Fiction Writers. And if you enroll before September 1st, you get half off using coupon code EARLYBIRD.

C. S. Lakin is an editor, award-winning blogger, and author of twenty novels and the Writer’s Toolbox series of instructional books for novelists. She edits and critiques more than 200 manuscripts a year and teaches workshops and boot camps to help writers craft masterful novels.

The post How to Effectively “Tell” Emotions in Fiction appeared first on Storyfix.com.

August 6, 2019

An Interview… With Content About the Writing Journey

My friend Debbie Burke, a leading voice within the thriving Montana writing community and a columnist for The Kill Zone blog (as I was for a couple of recent years), has posted an interview with me about my new book, “Great Stories Don’t Tell Themselves,” which releases October 8 from Writer’s Digest Books.*

Debbie and I both believe that anything we put online, even something with an agenda (as in, “hey, please notice my new book, which is available for pre-order now!) needs to deliver something of value to the reader. Which is the whole point. This interview goes there in spades, and I think it’ll get your writer’s brain ticking on a few fronts.

You can check out the interview HERE.

****

Debbie Burke’s novel, “Instrument of the Devil” is getting rave reviews on Amazon and other online venues. It’s the first installment in a series of Tawny Lindholm thrillers set in Montana.

*If you’re wondering about the recent changing of the guard at Writers Digest, including their book division, the parent company (F/W Media) has been sold off in pieces to various acquiring companies. The book division was purchased by Penguin Random House, but will continue to release books under the Writers Digest Books imprint.

Writers Digest Magazine was acquired by Active Interest Media, a robust mulit-media company with five focused groups. Likewise, they will continue to publish Writers Digest Magazine under that name.

The post An Interview… With Content About the Writing Journey appeared first on Storyfix.com.

July 25, 2019

Double What You Know About Storytelling with 5.5-hours of Intense Mentoring — An 11th-hour Workshop Opportunity

This will be unlike any writing workshop you’ve ever attended.

Next week I’ll be teaching at the 50th Annual Willamette Writers Conference, held at the airport Sheraton in Portland (August 1-4). This will be my tenth appearance at that conference over the last 12 years, and over that time I’ve become known as the structure guy, for reasons that make sense. I actually am the structure guy.

But there’s a downside to a focus on a specific facet of craft, as well as being a familiar commodity to the audience. Many of those folks will see my name on the agenda and think, “saw him before, got it, thanks, moving on.”

But this year is different. In addition to two regular conference workshop sessions, I’m presenting a 5.5-hour Master Class—”CRITERIA-DRIVEN STORYTELLING: USING BEST-IN-INDUSTRY STANDARDS TO STRENGTHEN YOUR NARRATIVE“—on the Thursday before the regular conference (August 1), one of several great Master Classes offered that day.

Here’s how my Master Class this year will be different.

While some structure stuff will be included, it’s actually a subset of a wider body of essential craft knowledge. Commanding the entire spectrum of story criteria can cut years off your learning curve and immediately escalate the efficacy of your current work-in-progress.

This craft knowledge is what experienced pros understand, and newer writers often struggle to learn (because it isn’t always obvious, and it is always multi-faceted). This workshop will explain why some stories get published and read, and why others fall short.

Here’s how and why that’s a true statement.

When was the last time someone at a writing conference heard your pitch, and instead of nodding and saying something polite, even if they took a pass on it, they actually gave you the feedback you need at the core idea level? Feedback, as in, the story isn’t strong enough. The idea isn’t original enough, or compelling enough.

So, feeding off that polite but empty response you received instead of that feedback, you go away and write the story—the one built around a less-than-compelling core idea—applying all those niche-skills you learned at that and other conferences. You sweated out a strong opening. The dialogue crackles. Your hero has an empathetic inner life. Your fight scenes are rendered with vivid realism. All the stuff you learned at the last conference.

And then, months or even years later, after you’ve finished (buckets of blood and sweat) and sent the book out into the world (lying awake at night second guessing yourself), you begin to get feedback that, while the writing is solid, the story at its core isn’t strong enough (self-published authors encounter this in the form of critical, even snarky reviews). Which was information available to you back at square one, if only you had known. If only someone who knew better had taken the time to tell you the truth, and shown you how, specifically, you could have elevated and enriched that core story idea.

You didn’t know, back there at square one, what you didn’t know.

That’s the essence of this workshop.

To fill in the gap between what you don’t know and the dramatic principles of storytelling that you need to know before the story will work… optimally. Which should always be your goal. Even if you believe you know what you need to know, or some of it, but you haven’t got it all down yet, that gap still remains… like someone who knows how to swing a golf club, chances are you aren’t yet ready to try for your tour card.

The core essence of your story’s idea is as much as half of the value proposition that readers, agents and publishers are looking for. Great stories don’t write themselves, and especially in genre fiction, greatness is seeded and imbued at the core idea and premise level.

Readers won’t show up for your beautiful writing. That’s just a fact. They’ll show up for a story that leaves them breathless and emotionally engaged.

Also, they (readers) couldn’t care less what your creative process is.

Here’s why this workshop may feel like something you’ve never encountered before.

Not only is the craft and skill and fundamental essence of landing on a rich and compelling story idea rarely touched upon within the writing conversation (the September issue of Writers Digest Magazine recognizes this; the central theme of it is, in fact, The Big Idea. Which is why, by the way, my new book, described below, has a full page ad on page 69), the notion of criteria applying to it is foreign to the discussion.

Instead, much of the teaching and mentoring about storytelling either focuses on, or is dependent upon, the process of the writing, delivered in a room full of writers that is quietly all over the place in that regard. Too often that leaves the nature and criteria of the end-product (including the core story idea itself) either under-served, or at least somewhat muddy. Hence, the need for multiple drafts before the story solidifies… if it ever actually does.

For all writers and all processes, the ultimate end-product is the sum of two things: what the writer knows (both about what a story requires as a matter of principle, and what the WIP requires as a matter of specificity), juxtaposed with what the writer doesn’t know (again, relative to the principles of storytelling and the WIP itself). Which leaves newer writers looking up at a very steep hill.

What they need to know are the criteria that apply to each and every part and element and essence of a story that works. Including that initial story idea that, hopefully, ends up as a viable dramatic premise (which has a separate set of criteria than those that apply to the idea… you get the idea of the nuanced understanding required).

To complicate matters, too often writers don’t actually know what they don’t know, which is precisely why writing a publishable story is so challenging, and why the percentage of rejection is so frighteningly high; 94 percent of stories submitted to publishers by agents are rejected at least once… even if the agent initially took on the project, which is another low percentage statistic.

This Master Class not only delivers the foundational core information that makes a story idea glow in the dark, it also explores what causes a completed manuscript to sizzle in the reader’s hands. Unlike most workshops that tell you how to find your story (the options are endless, including the inside-out advice that Story Trumps Structure, which is 100 percent a process-oriented context), this workshop is process neutral. Once you are in command of this criteria-based knowledge, how you go about finding your story isn’t the issue; knock yourself out, you’ll be a better pantser if that’s your thing, a better outliner if that’s you, and a better everything in between—as it breaks “story” down into component parts while assigning specific criteria to each part, as well as a mission-driven context relative to the whole of the story.

Because this is information rarely encountered within a holistic context, it is a learning experience unlike anything you’ve experienced. The workshop delivers the raw grist of my new writing book—GREAT STORIES DON’T WRITE THEMSELVES: CRITERIA-DRIVEN STRATEGIES FOR MORE EFFECTIVE FICTION—which will be published by Writers Digest Books in October. Too late for the WW Conference bookstore… but… those who attend this workshop will receive a digital advance reading copy, which contains definitions, context and examples of all of the 70-plus criteria involved.

Bestselling Northwest author Robert Dugoni, who wrote the Foreword to the book, says “this is the stuff you wish you’d learned early-on in your writing journey.” It is designed to make your learning go vertical, while putting the story on your desk, your WIP, on steroids.

Bestselling Northwest author Robert Dugoni, who wrote the Foreword to the book, says “this is the stuff you wish you’d learned early-on in your writing journey.” It is designed to make your learning go vertical, while putting the story on your desk, your WIP, on steroids.

Click HERE to view the WW Conference page for this workshop. From there you can navigate to information about how to sign up.

If you’re looking for a milestone moment in your writing journey and growth, this is an opportunity you should consider.

*****

I will also be teaching this Master Class at the Writers Digest Annual Novel Conference, held in Pasadena, CA, October 24-27 (this, too, will be a full day workshop held on the 24th, the day before regular conference, where I will also present two session workshops. CLICK HERE for more on this great event.

The post Double What You Know About Storytelling with 5.5-hours of Intense Mentoring — An 11th-hour Workshop Opportunity appeared first on Storyfix.com.

July 5, 2019

The Secret Weapon of Successful Novelists… is Also the Most Obvious

by Larry Brooks

Life and art are funny this way.

Sometimes the most powerful truths are right there in front of us all along. And yet, when we encounter them along the path, we step right over that stone instead of peeking beneath to harvest its value.

Comedic genius Steve Martin (if that’s a new name to you, then you were probably born after the Y2K scare) says he knows how to avoid paying taxes on a million dollars. We all want to know, right? The answer is this: “Well, first, you get a million dollars…”

Which for novelists translates like this: for new writers especially, the key, the trick, the secret entry code to breaking into the business–indeed, to writing a bona fide bestseller–is to come up with a million dollar story idea.

And yet, hardly anybody at the writing conference it talking about that.

As the release date for my new writing book (“Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves“) approaches (note the countdown clock to the right of this post), I’m starting to do some interviews and field the common question within them that is, essentially, this:

How is this book different than your previous three writing books? What is the Bright Shiny Object that powers this new book? What makes it unique in the massively bland sea of writing books that all seem to be a repackaging of the same things, if not simply one author talking about their preferred process, which is entirely different than talking about what makes a story actually work at its core?

Here’s my answer, framed by the proposition that each of the key phases, elements and essences of a functional story (novel or screenplay) can be driven by, and juxtaposed against, a set of universal principles–expressed as criteria–that define what, how and why the element and essence in question does, in fact, work.

In other words, how and why the story resonates with readers. How the writer can optimize their choices across the entire arc of the story… beginning with the core idea itself.

That alone separates the book from everything else on the craft shelf. The book presents and analyzes over seventy specific criteria that fuel those various essential phases, parts, elements (like scenes and transitional milestones within story structure) and essences of a story.

But where’s the million dollar answer to that question about the story idea? It is this:

The book frames, defines, discusses and exemplifies the key criteria that apply to story ideas that glow in the dark. Including the inescapable logic of why you need your story idea to glow in the dark if you are serious about competing for readers in a professional marketplace.

Once again, screenwriters are a step ahead of novelists in this focus.

I’ve been saying this for years: if you want to hop into the fast lane of learning how to write stories, study screenwriting. They learn more in the first week of an intensive course of study that some novelists encounter over years, even decades.

Just today, as I was cruising around Amazon to see what’s new on the craft shelf, I found a title by screenwriter Erik Bork: The Idea. And I realized that he was preaching from the same choir loft that I am. To wit, here’s what the front-matter on that book’s Amazon page says:

But even the best fiction writing books and screenwriting experts tend to move quickly past the crucial step of choosing a viable idea, to get to the specific plotting and composition of it, because there is so much to master in those later parts of the process — which feel a lot more like “writing” than developing and mulling over potential story concepts.

Professionals, though, tend to understand the primacy of “the idea,” and learn that there are certain key elements in story or series premises that really work, and which are worth investing time and energy in. And that’s what The Idea focuses on — laying out what those specific elements are, and how to master them.

Amen, brother Erik. He may not even realize how rare it is for a novel writing workshop, or teacher, or published author, to tell us what constitutes a Big Idea, and what the various criteria for recognizing and exploring that idea consist of.

Which is precisely how my new writing book is different.

Not only from my prior writing books, but from pretty much any other fiction writing text you’ve read. It’s about the primacy, the inherent power, of a story idea that works, which is defined by the way the idea gives way to a fully-functional story premise.

And then, how to apply specific criteria to each expositional step of bringing that premise alive on the pages. Not just the idea, but across the entire arc of your novel.

Within my book’s macro-framework of assigning criteria to the full arc and art of a novel, part by part, scene by scene— imagine, for example, crafting your story’s Midpoint story-turn in context to a fuller understanding of the Midpoint’s mission with the macro-arc of the story, and the three specific criteria that ensure its functional efficacy–a full third of the book focuses on how to raise the level and enrich the promise of the story idea itself, which in turn puts all of the rest of the story machine into a higher gear, both dramatically and emotionally.

Of course, the final judgement of what makes for a strong idea versus a lesser idea remains imprecise and personal. But consider this: roughly half of the rejections issued by agents, publishers and readers (via bad reviews or simply deciding to not read the thing) connect to the strength of the core story idea itself… it’s promise, its inherent potential, its originality, the buttons it pushes, the initial response it causes.

The entire notion of what a story idea is, how it evolves into a story premise (if you think they are the same thing, then you are wildly undervaluing the role of your idea in the entire storytelling proposition), is presented, analyzed, and broken down into a core mission, and then three specific criteria, one of which is a total game changer that becomes evident (after you finally see it more clearly) in virtually every breakout bestseller you’ve ever read.

Once you’re certain your story idea is indeed one that glows in the dark, what happens next takes on a blissful new urgency full of empowerment. Because now you’ll have the empowering contextual awareness of the part-specific criteria that ensures the story lives up to the promise of your brilliant idea… by turning you into a brilliant storyteller, as well.

Here’s a taste of what you find in Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves, lifted from the Introduction:

It is rare, even unheard of, when someone in the writing community will tell you that your story idea isn’t strong enough. It’s as if the default position—to an extent that it is commonly considered to be part of the conventional wisdom—is that a writer can and should write anything they want. Even that they can define what a story is, when in fact the idea may not qualify as a criteria-meeting story at all.

This is no different than believing we can and should eat and drink anything—and as much as—we want, when there are principles that clearly show us we cannot do so and simultaneously seek a high level of health. Ice cream for dinner every day… sooner or later there are consequences.

When a friend or a writing teacher allows you to settle for a thin or weak idea, simply by refraining to tell you that they don’t see great potential in your story idea, they haven’t served you. Or possibly, they aren’t able to differentiate a strong idea from a vanilla one at this early stage. They nod and smile and say, “Wow, that sounds terrific!” When in fact, it actually doesn’t, as least to someone who understands the criteria for a good story idea at its core.

Rejection may be the closest you’ll get to an assessment in that regard.

Here’s what you’ll understand, once you’ve read my new book: Not every idea for a story is a great idea for a story.

And much like that sow’s ear aspiring to become a silk purse, knowing how to craft a well-told story (itself a criteria-driven sensibility) is often not enough to elevate a vanilla idea to the level of dramatic and emotional resonance readers are looking for.

Consider that you no longer have to simply guess. Or bet the farm on your own assessment of what makes an idea strong, or not. Armed with, and informed by, proven criteria that can in retrospect be applied to virtually any story that works, you no longer need to be alone with those odds.

*****

Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves: Criteria-Driven Strategies for More Effective Fiction will be published by Writers Digest Books (a division of Penguin/Random House) on October 8, 2019. You can pre-order on Amazon here, or on BN.com here.

The post The Secret Weapon of Successful Novelists… is Also the Most Obvious appeared first on Storyfix.com.

June 20, 2019

An Interview With Bestselling Author Robert Dugoni

Just possibly the hottest author in the business right now.

Just possibly the hottest author in the business right now.If you think that’s hyperbole, consider this: shortly after his new novel — The Eighth Sister — launched in early April, Amazon updated their Author Ranking list, and he was just that: he was in the #1 slot. The second most popular author that week was some Brit YA writer named J.K. Rowling.

I think you’ll admit, that’s something few of us would admit to even aspiring to.

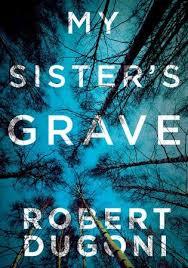

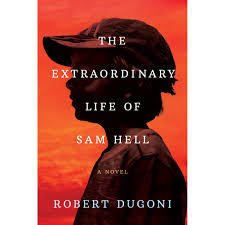

That book, which is a spy thriller inspired by a true story, comes smack in the middle of his sizzling mystery/thriller series that launched with My Sister’s Grave (2014, also from Thomas & Mercer, with over two million copies sold and counting, with the subsequent six titles in the series all hitting multiple bestseller lists). And if that wasn’t enough, his self-described magnum opus, The Extraordinary Life of Sam Hell (2018, from Lake Union Publishing) is a multiple-award winning darling of the book club circuit with over 3200 Amazon reviews (82 percent 5-stars), and is reportedly making John Irving nervous.

All of which makes me, in a much quieter way, one of the most blessed authors in the business. Because Robert Dugoni wrote the foreword to my new writing book, Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves (October, from Writers Digest Books). And he’s the ideal candidate to do it, since he also teaches frequently on the workshop and conference circuit, and, like me, is a stickler for craft, while being a nice counter-point to my planning-centric approach… because Robert Dugoni is a more organic writer, what we sometimes refer to as a pantser without the slightest implication of judgment.

He’s proof that pantsing, just like like story planning, isn’t the high or the low road to success, or even an explanation for it. It’s simply a preference of process… and only that. Both pansting and planning/outlining require a keen sense of story, built upon a dues-paid, thick-skinned apprenticeship during which the principles and criteria of craft become self-evident, omnipresent and non-negotiable, and thus — and it doesn’t happen for everyone — part of the writer’s DNA.

The mission of this website is to share knowledge and inspire a vision for stories and careers. No better way to get back into the lane than with an interview like this one.

*****

LB: Inquiring writers want to know… does a rollout like the one you’ve just experienced (The Eighth Sister) ever get old? How many appearances did you make? What’s the craziest thing that has happened on this one… and the best thing?

RD: Touring for a new novel can be exhausting. I once was on the road for 23 days – something like 12 cities. There’s not a lot of glamour involved. You often don’t have time to even see much of the city. Working with Amazon publishing I can be much more selective in my appearances and the timing of those appearances. They are also constantly looking beyond the norm, trying to find events that will help move the needle. They often use one appearance for multiple purposes.

For example, for The Eighth Sister they combined a book signing with a wine tasting and light Hors d’oeuvres at Chateau San Michelle winery in Woodinville. It was a great evening and everyone really had a good time. That would have to be the highlight of this tour. The craziest night was my experience signing with Lisa Scottoline at the Poisoned Pen in Phoenix. She’s very funny and she’ll say just about anything. It made for a wild night and a lot of fun.

For example, for The Eighth Sister they combined a book signing with a wine tasting and light Hors d’oeuvres at Chateau San Michelle winery in Woodinville. It was a great evening and everyone really had a good time. That would have to be the highlight of this tour. The craziest night was my experience signing with Lisa Scottoline at the Poisoned Pen in Phoenix. She’s very funny and she’ll say just about anything. It made for a wild night and a lot of fun.

LB: What’s the best question anyone has ever asked you about your writing process, and the craft that underscores it? I think we can intuit the obvious and perhaps insidious questions, but does something stand out as incisive or rare?

RD: I was teaching a class one time and talking about plotting and character development and this poor guy in the class just looked forlorn. He finally raised his hand and he said, “You do all of this on the first draft?” And it made me realize that I wasn’t teaching writing. I was teaching craft. I wasn’t teaching the first draft. I was teaching the second and the third draft. So I stopped and I told the class, the first draft is your draft. It’s your chance to get your story out of your head and onto the page. I’m a big believer in not self-editing a first draft, to let your subconscious flow and to just get out of the way of the story. On the second draft, and the drafts thereafter, however, you’re no longer a writer. You’re an editor. That’s when you’re looking to cut and to edit and to change what you’ve crafted knowing the principles that you’ve studied and learned. Now I tell everyone of my students at the beginning of the class – the difference (for me) happens between the first and the second draft.

LB: How does the relationship between your work as a conference workshop presenter inform your work as a novelist? Or vice versa?

RD: I liken the experience to a mechanic working on everyone else’s cars. It forces you to evaluate what works and what doesn’t and why. It helps you to see when an engine is running smoothly and when it needs some work. Teaching reinforces all the principles that go into writing a book. For instance, letting the character tell the reader what he wants in every scene, so the reader has a vested interest in that scene and in that character succeeding. Then putting obstacles in the path of the protagonist’s goal to create tension in that scene. When I teach, I’m learning. When I’m learning, I’m a better writer.

LB: If ten bestselling authors gave a workshop, I believe we’d get ten takes on how its done, and why. Do you agree? What is the common ground to listen for, and how do we explain to new writers when they hear one credible author say one thing, and another say something completely different on the same issue?

RD: I do agree. It is one of the reasons why I never teach process. I teach principles. I liken my teaching to being a golf coach. Every person who swings a golf club does it a little differently. But if the person is getting results, there’s no reason to correct the swing. If a golfer is slicing the ball, a good golf coach will first tell the student the principal behind the ball slicing so that the student knows and understands why the ball is doing what it is doing and can then seek to fix it. I ask students all the time, “Should a character change throughout a novel?” They all say, “yes” because they’ve read somewhere that characters should change. So I then ask, “Why?” You’d be amazed at the blank stares I get. I ask, “How much should a character change? More blank stares. If a student doesn’t understand the principal behind a character’s need to change, how can they fix it? I tell students to study the craft and then find what process works best for them. But I also tell them don’t be stubborn. There are certain principles that underscore all good fiction – plots that move, characters in action, tension, tension and more tension. Ignore those principles and the process doesn’t matter..

LB: I’ve developed a hypothesis: relative to that variance between what writing teachers and gurus and authors are saying about what a novel is, how we do the work, and why… I believe the only real debate concerns process. That the outcome we seek is really beyond debate–the criteria that makes a novel work, or when skipped or minimized, cause it to just sit there–and is absolutely something that can be defined, taught and learned. But when the discussion polarizes relative to process it seems to also polarize what we believe about the fundamentals, as well (thus licensing the “there are no rules” guys), and that can confuse and even prove toxic to some writers.

What do you think about this issue? As for me, I’ve become avidly process-neutral, while becoming more clear on what the craft offers and what it demands of the books we create.

RD: I think you hit it on the head and essentially repeated what I just said. I agree wholeheartedly. How an author works – whether she outlines or is an organic writer, is that writer’s process. Whether they edit their work as they write or just barf out a first draft, is their process. Whether they work during the day or at night, whether they listen to music or need silence, is part of their unique process. I once taught with a woman who said “Writing is just one rule. It needs to work.” Well, that’s great, but if a new writer follows that one rule, then how do they ever learn?

A teacher might say, “It’s not working.” Then the writer asks, “Why not?” To which the teacher answers, “Well, that’s part of your process. So you have to figure it out.” And round and round we go.

No. A good teacher says your process isn’t working because you don’t understand the principles of the craft. You don’t understand that a strong opening needs a hook, having the reader meet someone interesting right away, someone they can can root for, if not relate to, and a tangible goal that character needs, with desires or wants, but that’s out of reach or feasibility at first. They can’t have what they want because of certain obstacles that create tension and drives good fiction. If you don’t understand the fundamental purposes of an obstacle then the middle of your book will sag because it is repetitive, there is no forward motion to the story. Your ending is unsatisfying because you don’t understand the principles that lead to a satisfying ending.

In short, you may be hitting a thousand golf balls everyday but you’re hitting them all the wrong way, so you’re not getting any better. You’re just reinforcing bad habits.

LB: What would you say to your younger writer self about something you know now that you didn’t know then? Perhaps an example of, “I didn’t know what I didn’t know.”

RD: Writing is a craft. Learn the craft. Yes, it’s true that just about everyone can write. But just about everyone can also hit a golf ball – that doesn’t make them a professional golfer. You’re not just “writing”. You are story-telling. And if you don’t know all that is involved in telling a great story, you can’t possibly build a great novel people are going to want to read.

LB: You’ve written a killer Foreword for my new writing book (the editors at Writers Digest Books are in love with you, I think). When Michael Hague wrote the Foreword to my last book, he admitted that he had to pause because the way I frame the principles caused him to rethink the way he teaches them. It ended up great, by the way, he realized we were on the same page with all of it, that there are many roads leading to enlightenment. I’m wondering if there was any such integration issues or hesitance on your part?

RD: Yeah, there was. But I think that goes back to the process more than the principles. You and I both agree that you have to learn the craft. I teach those principles one way. You teach them slightly different. But we’re both saying the same thing.

We’re both teaching the reader that at some point in your novel you need an inciting incident. You need the protagonist to commit to the journey. You need an opposite force pushing against what the protagonist wants so they can’t have it, either easily or quickly. Screenwriters are very specific about the craft and principles. They go so far as to say, by page 10 of a romance this has to happen. By page 25, this has to happen. The principles haven’t changed, but the message has. Why? Because screenplays are usually 120 to 200 pages. The screenplay is written for a different medium – one that is experienced through sight and sound. So it is imperative that certain things happen at certain times. But that is really process, not principal. The principles are the same. The process to achieve those principles is different because it is a different medium.

LB: The Eighth Sister is, we now know, becoming widely regarded as a masterpiece. When you write something that is that well received, how do you face the blank page with the pressure, and perhaps the intention, to top yourself with your next novel?

RD: I never think of anything I’ve written as a masterpiece, though I appreciate the kind words. I’m always pleased if my work is well-received by readers, but as much as I love getting those emails, there’s nothing anyone can say that will make me go and change the novel. It’s done. That story is written. It’s out in the world existing. When it is, my world has changed a bit, but my job hasn’t. My job is to write the next novel, maybe a better novel, with better characters and a killer climax. That’s the fun part of this job, always trying to write a better novel, to top oneself. I really admire Stephen King because he’ll write this terrific novel, like The Shawshank Redemption, or the Green Mile and before you’re even finished reading that masterpiece, he has another book come out. It’s kind of the way I heard Gene Hackman described. He’s a working actor. He’s always working. He’s versatile and skilled and always taking the next role because that’s what he does. He’s an actor. Sometimes he’s going to find gold. And sometimes he’s just going to play his part. That’s how I’d love to shape my career. A working writer, putting out the next novel that’s hopefully better than the last, but at the very least, is the best I can offer.

LB: I feel like I’m constantly thanking you for you willingness to weigh in on my work, and most lately, to be included in my book with this Foreword, as well as indulge me with this interview. But mostly I want to thank you, not only for your friendship, but for your inspiration and the way you lead us to the high bar to which we all aspire.

And for the books. All of them. That body of work, alone, is a gift to us all.

*****

And by the way… Robert Dugoni is still entrenched on Amazons Top 1o0 Author Rankings, even with his new novel’s launch two months in the rear-view mirror.

*****

More About Robert Dugoni

Robert Dugoni is the critically acclaimed New York Times, #1 Wall Street Journal, and #1 Amazon best-selling author of the multi-million-selling Tracy Crosswhite series. The first entry, My Sister’s Grave, has sold more than two million copies, has been optioned for television series development, and has won multiple awards and nominations. He is also the author of the best-selling David Sloane series, nominated for the Harper Less Award for legal fiction, and the stand-alone novels The 7th Canon, a 2017 finalist for the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for best novel, and The Cyanide Canary, A Washington Post Best Book of the Year. His latest novels include the award-winning The Extraordinary Life of Sam Hell, and The Eighth Sister, which debuted on several best-seller lists and elevated him to the #1 ranked author on Amazon.com. He is the recipient of the Nancy Pearl Award for Fiction, and the Friends of Mystery Spotted Owl Award for the best novel in the Pacific Northwest. He is a two-time finalist for the International Thriller Writers award and the Mystery Writers of America Award for best novel, among many other awards and best-of inclusions. His books are sold worldwide in more than twenty-five countries.

Learn more at his website, www.robertdugonibooks.com.

The post An Interview With Bestselling Author Robert Dugoni appeared first on Storyfix.com.

June 5, 2019

FLASH SALE: Deep discounts on Story Analysis Services

I know, things have been quiet here lately.

Some of you have checked in, some of you have checked out altogether. But there’s a reason, if not an excuse: I’ve been busy finishing the editing phase of my new writing book — “Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves” — working with the fine editorial staff at Writers Digest Books, who have published all three of my prior writing books.

With the completion of final edits comes a passing of the baton. They now move on to the work of final print design, digital conversion, listings with online booksellers (the Amazon page is up, though the book cover is still not displayed; check back for that soon) and order fulfillment for bookstores, all of which in effect clears my desk. (There’s a still-fuzzy peek at the cover at the upper right of this page, and at the right margin of the header at the top of this page.)

I can’t think of a better way to get back in the groove here at Storyfix, in addition to recommencing a series of posts that dive into the content of the new book, which is really fresh ground in the writing conversation), than to incent a few of you to opt-in to my story coaching services… with a win-win discount to get us going.

The Discounts

As I explain in the middle column to the right, my story coaching takes three different levels, each with a unique approach and its own value pricing. Click through from there to read about the scope, the feature-set and the value proposition of each levels.

The Full Manuscript Analysis, normally $1950 (fee varies for manuscripts over 90K words and under 75K words), is available through June (for order placement; actual timetable is something we’ll negotiate) for just $1200, a savings of nearly 40 percent. I’ll analyze your story across a robust set of checklists from 14 different categorical core competences and essential narrative facets, with a liberal dose of aesthetic assessment and market viability slathered on top of it all.

The Core Premise Analysis, working from a challenging Questionnaire that will allow us to make sure your story intentions are strong and market optimized — in other words, ensure that your story idea is worthy and promising, not only to you, but to a hungry marketplace of readers — is normally $195 (which includes a revision round). Through June, the fee is only $150. Because half of all rejected stories are explained at the story idea/concept/premise level, no matter how well written they are, this is some of the best money you can spend on your story at any stage of its development.

It’s like getting a full physical before entering your first triathlon. You don’t want to fall out of contention at the first turn.

And finally, I’m resurrecting my First Quartile Manuscript Analysis, which includes the same Premise Questionnaire and evaluation as well as a read of your first 100 pages (up to your First Plot Point story beat), for only $450. Because almost every manuscript exposes itself as worthy (or not) in the pages leading up to the First Plot Point, this level provides nearly the same value proposition as the Full Manuscript eval at a fraction of the cost (and a fraction of my time), since it includes a template for you to disclose how the rest of the story will flow and ultimately resolve, which is also part of the analysis.

Here are the caveats.

This is a first-come-first-served offer, since I don’t want to over-commit. For June I’ll accept the first two Full Manuscript takers, the first 10 Premise Analysis takers, and the first five First Quartile takers. After that everything pushes into July and August, which may or may not find these discounts still in play (depending on the resulting workload).

Let me know (storyfixer@gmail.com) if you have questions. Or you can pull the trigger by processing your payment (to the same email as payee) through Paypal.

I reserve the right to accept or reject projects based on suitability and market viability (with immediate full refunds, of course; example: if your story is, beat for beat, a thin imitation of a famous novel, or if the writing just isn’t ready for a professional audition)… in cases where I don’t think I can help you. Sadly, this happens when an author jumps into the ring before they adequately understand the nature of the game.

If you are anywhere in the ballpark, though, I can show you with specificity what it will take to push your novel over the edge and into the game itself, either as someone seeking publication or aspiring to success as a self-published author. If you’re already at that level, I’ll be more than delighted to affirm that for you, either in terms of the viability of your story, the state of your execution and writing voice, or all of it already clicking in harmony to each other.

In the meantime, I’ll be continuing a buff-up of this site and offering posts on all aspects of the craft, including an exclusive interview with author Robert Dugoni, who wrote the Foreword for my new book, and is currently among the hottest authors on the planet with his new book, The Eighth Sister.

The post FLASH SALE: Deep discounts on Story Analysis Services appeared first on Storyfix.com.

April 12, 2019

Download available : Unlock the Power of Criteria-Driven Story Development

… presented by Larry Brooks as a live-narration, Power Point visualized lecture, with a run-time of one hour and twenty minutes.

This virtual workshop from Writers Digest University was part of WD’s recent Mystery and Thriller Virtual Conference.

The download is available HERE for $79.99

SESSION DESCRIPTION

This workshop is about elevating the efficacy of your writing process, without asking you to change it. In doing that, the focus isn’t on process, per se; rather, this session will focus on the outcome of your process, framed as element-specific target criteria.

In the mystery and thriller genres especially, audiences have specific expectations, as well as a high bar. While a story may emerge organically for the writer, rare is the story that ticks off the requisite boxes at that early stage. There are craft-specific strategies to help you meet the criteria for an effective mystery or thriller, regardless of whether you are a pantser (an organic story developer) or a plotter/planner/outliner. The criteria, and the desired/optimal outcome, are exactly the same.

Experienced authors understand that the criteria for the first part of a novel are very different than the middle or the end (which are also unique, criteria-wise). But even that is overly simplistic. This workshop will reduce the core bones of an effective mystery or thriller down into specific elements and essences, giving you context for the creative decisions you must make within each of them.

Half the battle is won at the story-idea stage, and how that translates into a complete – and completely functional – dramatic premise. There are specific criteria for this, which frame the efficacy the parts and parcels that emerge from that premise.

You may have studied the basics before now. This is a deeper dive into what makes bestsellers out of otherwise pedestrian story ideas, and what makes career-authors out of those who still seek the nuances and true purpose of the craft principles that can unlock the highest potential of the work.

This material is a high fly-over of my new book, Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves: Criteria-Driven Strategies for More Effective Fiction — which releases in the fall from Writers Digest Books. In a field in which it may seem there is rarely anything new to discover, this is a fresh and comprehensive approach for writers who seek to know as much as they can about how and why novels work at the deepest levels, and how to access and apply those fundamental principles.

The post Download available : Unlock the Power of Criteria-Driven Story Development appeared first on Storyfix.com.

Download available soon: The 5th Annual Writers Digest Mystery & Thriller Virtual Conference

This virtual workshop from Writers Digest University took place over the weekend of April 12/13. It concludes one hour presentations (slides and audio) from s even authors who are also writing teachers, include real-time Q&A.

Check the WDU website (HERE) to access these sessions on your timetable, in your home or office or favorite coffee shop (headphones are a good idea in that case).

I presented an information-dense workshop that, for many, could change the course of their writing journey:

SESSION 4: Unlock the Power of Criteria-Driven Story Development

INSTRUCTOR: Larry Brooks

SESSION DESCRIPTION:

This session is about elevating the efficacy of your writing process, without asking you to change it. In doing that, the focus isn’t on process, per se; rather, this session will focus on the outcome of your process, framed as element-specific target criteria.

In the mystery and thriller genres especially, audiences have specific expectations, as well as a high bar. While a story may emerge organically for the writer, rare is the story that ticks off the requisite boxes at that early stage. There are craft-specific strategies to help you meet the criteria for an effective mystery or thriller, regardless of whether you are a pantser (an organic story developer) or a plotter/planner/outliner. The criteria, and the desired/optimal outcome, are exactly the same.

Experienced authors understand that the criteria for the first part of a novel are very different than the middle or the end (which are also unique, criteria-wise). But even that is overly simplistic. This workshop will reduce the core bones of an effective mystery or thriller down into specific elements and essences, giving you context for the creative decisions you must make within each of them.

Half the battle is won at the story-idea stage, and how that translates into a complete – and completely functional – dramatic premise. There are specific criteria for this, which frame the efficacy the parts and parcels that emerge from that premise.

You may have studied the basics before now. This is a deeper dive into what makes bestsellers out of otherwise pedestrian story ideas, and what makes career-authors out of those who still seek the nuances and true purpose of the craft principles that can unlock the highest potential of the work.

Other Presenters include…

… James Scott Bell, Naomi Hirahara, Gar Anthony Haywood, Hank Phillippi Ryan, Jane K. Cleland, and Paula Munier. The collective whole of the conference dissects the entire proposition of writing a mystery or thriller (or even a mystery/thriller), from idea and premise, to character and plotting, to making the middle sizzle, and how to infuse your scenes with killer tension.

There will also be agents, chat rooms and other features available to attendees. The presentations will remain available to you at no further charge via Writers Digest University.

This is your chance to take your skills to the next level with hard-core mentoring on the criteria, nuances, traps and tips of writing mysteries and thrillers that compete at a professional level, and because of that will get the attention of agents and traditional publishers, as well as readers who seek out the best independently published fiction.

Check it out, and sign up, HERE.

******

If you’ve wondered where I’ve been, I’ve been finishing the new book for Writers Digest — Great Stories Don’t Write Themselves: Criteria-Driven Strategies for More Effective Fiction — which releases in the fall. It’s just now coming out of editing, and soon I’ll be back here on Storyfix soon to explore a variety of topics from within the context of being a Criteria-Driven author. In a field in which it may seem there is rarely anything new to discover, this is a fresh and comprehensive approach for writers who seek to know as much as they can about how and why novels work at the deepest levels, and how to access and apply those fundamental principles.

Thanks for hanging in there with me. The best is yet to come!

Larry

The post Download available soon: The 5th Annual Writers Digest Mystery & Thriller Virtual Conference appeared first on Storyfix.com.

Happening this weekend: The 5th Annual Writers Digest Mystery & Thriller Virtual Conference

Presenting a live virtual workshop from Writers Digest University.

Seven authors presenting one-hour sessions – which include real-time Q&A – in the comfort of your own home or office; four on Saturday April 13, three more on Sunday April 14.

Just sign up (HERE) on the conference website, then log in for your chosen sessions to take a deep dive into various aspects of mystery and thriller craft.

I will be presenting a session on Saturday, 5:00 EDT (2:00 PDT), previewing the content of my new writing book from Writers Digest (Fall 2019) entitled:

SESSION 4: Unlock the Power of Criteria-Driven Story Development

INSTRUCTOR: Larry Brooks

SESSION DESCRIPTION:

This session is about elevating the efficacy of your writing process, without asking you to change it. In doing that, the focus isn’t on process, per se; rather, this session will focus on the outcome of your process, framed as element-specific target criteria.

In the mystery and thriller genres especially, audiences have specific expectations, as well as a high bar. While a story may emerge organically for the writer, rare is the story that ticks off the requisite boxes at that early stage. There are craft-specific strategies to help you meet the criteria for an effective mystery or thriller, regardless of whether you are a pantser (an organic story developer) or a plotter/planner/outliner. The criteria, and the desired outcome, are exactly the same.

Experienced authors understand that the criteria for the first part of a novel are very different than the middle or the end (which al also unique, criteria-wise). But even that is overly simplistic. This workshop will reduce the core bones of an effective mystery or thriller down into specific elements and essences, giving you context for the creative decisions you must make within each of them.

Half the battle is won at the story-idea stage, and how that translates into a complete – and completely functional – dramatic premise. There are specific criteria for this, which frame the efficacy the parts and parcels that emerge from that premise.

You may have studied the basics before now. This is a deeper dive into what makes bestsellers out of otherwise pedestrian story ideas, and what makes career-authors out of those who still seek the nuances and true purpose of the craft principles that can unlock the highest potential of the work.

Other Presenters include…

… James Scott Bell, Naomi Hirahara, Gar Anthony Haywood, Hank Phillippi Ryan, Jane K. Cleland, and Paula Munier. The collective whole of the conference dissects the entire proposition of writing a mystery or thriller (or even a mystery/thriller), from idea and premise, to character and plotting, to making the middle sizzle, and how to infuse your scenes with killer tension.

There will also be agents, chat rooms and other features available to attendees. The presentations will remain available to you at no further charge via Writers Digest University.

This is your chance to take your skills to the next level with hard-core mentoring on the criteria, nuances, traps and tips of writing mysteries and thrillers that compete at a professional level, and because of that will get the attention of agents and traditional publishers, as well as readers who seek out the best independently published fiction.

Check it out, and sign up, HERE.

******

If you’ve wondered where I’ve been, I’ve been finishing the new book for Writers Digest — Great Stories Don’t Writer Themselves: Criteria-Driven Strategies for More Effective Fiction — which releases in the fall. It’s just now coming out of editing, and soon I’ll be back here on Storyfix soon to explore a variety of topics from within the context of being a Criteria-Driven author. In a field in which it may seem there is rarely anything new to discover, this is a fresh and comprehensive approach for writers who seek to know as much as they can about how and why novels work at the deepest levels, and how to access and apply those fundamental principles.

Thanks for hanging in there with me. The best is yet to come!

Larry

The post Happening this weekend: The 5th Annual Writers Digest Mystery & Thriller Virtual Conference appeared first on Storyfix.com.