Larry Brooks's Blog, page 11

July 20, 2016

The Passionate Cry of a Delusional Pantser

Let me be clear on something before launching into this: I’m not anti-pantsing or anti-pansters.

It’s not how I develop stories, nor is it something I recommend. But it is something I absolutely understand – with the exception of today’s little rant – and I’m clear on how it can work, when it works.

That’s the problem, you see. Many passionate pantsers aren’t really clear on how it needs to work. And they are the ones who are already composing a Comment here with a knee-jerk emotion… and thus, might just miss the point.

So please read the headline as intended.

I’m not saying pansters are delusional. Today I’m writing about one of the things some passionate pantsers say that is delusional. I’m certain story planners say delusional things, too – I’m probably among them – but look before you leap to a judgmental conclusion.

I have (looked, that is), and this is what I see.

Today I’m dissing one of the arguments – a single strand of rationale – that some pansters put forth as reasoning behind their pantsing preference. It’s like a kid saying he doesn’t like string beans because they are green.

They say that. And it’s ridiculous every time they do.

That single strand of pantsing rationale – not the other reasons that defend it – is exactly like that. Ridiculous. Which I’ll explain clearly in a moment.

I could – perhaps should – write a book about How To Pants Your Book Successfully.

Pansting is no different than any form or degree of story planning, relative to the criteria and elemental requisites for a story that is functionally and thematically sound. The bar is the same, and it is high with either process.

Too many writers pants for the wrong reasons. The more seasoned a writer is, the more likely they are to incorporate some form of story planning – if nothing else, then some alignment with the principles of story structure – into their process. Even if it all unfolds out of their head, without an outline.

That’s pantsing, too. The kind that works. Pantsing without a seasoned grounding in the principles of craft is the only option available to the new writer, or the stubborn resistant writer who denies the principles (and man, they’re everywhere out there), because in that case there is nothing to plan. It’s like trying to draw a house without ever really knowing how a house is built… you’ve simply been in a few houses in your life, so now you’re trying to build one without a blueprint.

Because hey, it’s fun to do it that way!

Pantsing is a process.

Nothing more. It’s not more artful or more mysterious than any other approach. It is neither qualitatively superior nor inferior.

It is, however, fraught with risk, in the same way that a pilot operating without a flight plan is inherently more risky than a pilot being guided by a regional air traffic controller from a flight plan filed in context to approaching weather, proximity to traffic and the length of the runway at the destination.

Both can land safely. The one without the flight plan – and here’s the important part, the part you should not miss – if bringing years of experience and training and understanding to the job, can probably weather an emergency (unexpected fog, low fuel, sudden wind sheer, an alien attack) as well as the pilot flying from a plan. Because they do know how to fly an airplane.

So, within this analogy, here’s what doesn’t happen: the pilot without a plan rationalizes that choice because it’s more fun. Or worse, say, “I just can’t read any of that flight plan stuff, my mind fogs.”

Thing is, this isn’t flying for fun. It’s professional flying. Just as we are talking about professional writing, writing to sell in a competitive market.

Here’s what doesn’t make it into the famous author interviews:

The iconic successful author who proudly waves the pantser flag – Stephen King and Diana Galbadon, as examples – has the expected structural paradigm and aesthetic bones of a story firmly implanted in their head, as an instinct. They don’t need a written plan any more than LeBron James needs a buzzer-beater play written out for him.

They know.

So if you’re Stephen King or Diana Galbadon or LeBron James, go ahead and wing it. Make it up as you go along. Have fun. But don’t fool yourself, you’ll be doing the exact same work as the other successful author – if, in fact, you are a panster writing from a keen awareness and story instinct; this is where the pantsing proposition crumbles under scrutiny – who is writing from an outline created in context to principles she or he understands to be inviolate and universal.

The same understanding, by the way, as that of their successful pansting peers.

It is the unschooled, less instinctual pantser that really can’t get away with claims of “I just can’t do it any other way,” or, “Planning takes all the fun out of it.”

Those are the battle cries of the naïve.

You’re writing a book to sell, right? So the “fun” part falls way down the list of priorities.

And the “I just can’t do it part” is a preference, not a principle.

The genius in the white coat who put the stent in your heart probably didn’t like mucking around the room temperature innards of a poor homeless guy when she/he was in Human Anatomy Lab 101, either, but here she/he is, saving lives and driving a German car.

Because the very thing that you, as a pantser, claim you just can’t do, is in fact the essential elemental composition of the very story you are trying to create.

If you just can’t create a story in outline form, then you just can’t create one in a draft, either. Both will require continued evolution, and if your story sense is weak, it will be extensive in either case.

A true story, not an analogy.

I know a guy, a great guy, who has the eating preferences of a 12-year old. We had them over for dinner not long ago, and served up some terrific homemade, freshly mixed guacamole as an appetizer. My guest wouldn’t touch it. Here’s the exchange when I asked why.

“I don’t eat that stuff.”

“Why not?”

“I just don’t.”

“You don’t like guacamole?”

He looked at with me a go F-yourself expression. I grinned back.

“No. I don’t,” he said.

“When was the last time you tried it?”

The look again. A cornered perp. No response.

“Do you like avocados?”

“Hell no.” His expression reminded me a little girl who had just stepped in her dog’s doody outside the backdoor.

“When was the last time you tried it?” I asked, stuffing an overloaded chip into my mouth.

He shook his head, the forehead of which was getting quite red.

“You’ve never tried it, have you.”

“Hell no.”

“You’ve never tasted an avocado, either, right?”

He shook his head. He was grinning at this point, realizing he was going down.

“So how do you know you don’t like it?”

No response.

“Go on, take a bite. Everybody likes guacamole. It’s delicious.”

He flashed me the palm of his hand when I moved a loaded chip his way.

My wife intervened. “Let him go,” she said.

“Sure. But you’re missing out on something really wonderful.”

“I don’t eat anything green,” was his final comment before my wife dug her fingernails into my shoulder.

Here’s my point for writers: My friend wasn’t trying to become a professional in the food business. He’s just being ludicrous because, other than embarrassment he pretends to not notice, there are no consequences to it.

But for you, the writer, the consequences can be significant.

Another True Story, Leading to Today’s Primary Point

Here is something I just read on another writing website, a pantsing rationale from an established writer that is repeated all the time, propagating like a sort of Zika virus of illogical crazy:

“ I’d say I’m a recovering pantser. Up until very recently, my mantra/excuse was, “If I figure out the plot ahead of time, I’ll have told myself the story and I’ll be bored and won’t want to write it.”

Yep. Because now that I know the story, I’m bored.

It’s not the process, folks. It’s the story.

Notice she said recovering pantser. And that she positioned her rationale as an excuse.

We’ll get back to her in a minute. But for now, know that…

The gold resides in those caveats.

For too many newer writers, that flip doesn’t register in their pantser brain. They cling to “I just can’t outline or plan,” and even, “It takes all the fun out of it.” I hear that battle cry constantly. It’s one of the reasons I don’t hang out on writing forums, because too many blustery novices put forth this nonsense within some faux context of artistic righteousness.

Which is ludicrous.

Other than the obvious, here’s why:

If you’re bored with a story plan, then how can you possibly be anything other than bored with a story you drafted organically, with no plan guiding you? Both are the expression of the exact same thing – a story unfolding from your instinct, from your inherent ability to sequence a story arc.

I’ll tell you how: because you evolved the story as you wrote it. It was better than it might have been at the outline stage. But that doesn’t legitimize the process, it simply states the writer was incapable of conjuring the best story at the outline stage.

That’s not something to brag about, that’s something to work on.

Planning or drafting are two different ways toward the same essential goal: the discovery of your best story.

Notice how this might translate to real life:

You work with an architect to draw a plan for, and a rendering of, your dream house. As you sit there, you grow bored. The house itself bores you. So instead, you back up a truck full of shovels and concrete and wood, and you build the house itself straight out of your head.

But you’ve never built a professional-level house before.

You’ll be too exhausted and frustrated to be bored. And, unless you have the talent and training of a professional, your house will look like something from a cartoon. A professional would never build a house without a blueprint, like you just did. Because it doesn’t work that way.

You’re not an artist in that case, you’re a beginner who doesn’t yet wield the requisite knowledge and skills. And the only way to find those things is by engaging at the principle-based story-bones level – as in, a story plan leading to an outline.

If you do that planning as a draft, then call it what it is: a story plan attempt, formatted as a draft.

Story is story. If you outline the bones of it and you’re bored by it, then the story isn’t good enough. Don’t blame the story… blame yourself. You have more work to do, and yeah, it may not be fun.

The same writer, sitting down to write the story that bored them as an outline, will experience one of two outcomes: the exact same story will manifest on the page (because it’s still you, doing this with the same level of story instinct), and you’ll be bored with it, too, for the same reason. Or, as you build, your instincts tell you to do something different, something better… and when you do that, you’re coming closer to a more functional story.

So have I just rationalized pantsing from the blank page forward? Yes… if and only if you have a story sense that is developed to the extent that you actually can recognize the moment and nature of something that isn’t working.

Which means, you could have recognized it at the outline level, as well. But didn’t.

Welcome to a paradoxical loop that leads to only one conclusion: no matter what your process, you need to evolve your story sensibilities and awareness of the principles of craft to a higher level, before you can render it to the page.

Then, write your story any damn way you choose. And you’ll choose some form of story planning when you get there, even if it remains in your head.

If you had that evolved level of story sense going for you, you would not be bored by the story at the outline level.

Because your story sensibility drives that, as well. In that case, your story would excite you, not bore you. And the draft you write from it would be the path toward elevating it, not just discovering it.

So when you hear a new writer claiming that outlining and planning takes the fun out of things, that it bores them, what you’re hearing is that the writer isn’t capable of conjuring up a story that works.

And as they draft, that same less-then-optimal story sense will realize a story that also doesn’t work, but they’ll be too immersed the forest of words and the fun of writing sentences and scenes to notice. They won’t even realize they are lost… precisely because their story sense can’t sniff out a lost dog of a story.

Ask any agent or editor. All day long they are reading stories that don’t work, precisely for this reason.

The interviewed writer above, the one who confessed that story planning bored her, went on to say this:

What I’ve learned—the hard way—is that there’s a lot of pleasure to be had in pondering plot and character before getting into the writing. And there’s much, much more to it than saying this needs to happen, then this, etc. The first inkling of each story nearly always comes to me as a vivid image—usually of a protagonist or a setting. But that’s not a heck of a lot to hang a novel on, and thus the plot often reveals itself with an agonizing slowness that undermines my production goals. I’ll get into this later, but for a long time I bought into the notion that the story was a sacred object, and if I manipulated it, it would become over determined and wouldn’t work.

She learned it the hard way.

Because the belief that planning a story will result in boredom is ludicrous.

It is the story itself that is boring, not the process.

If you’re a pantser, listen to how you rationalize your choice of process. Other less-then-enlightened pantsers won’t hear it, but the people that count – agents, editors, other writers with some seasoning under their belts – will hear any omission of logic, and they’ll silently feel bad for you.

Or they will reject your pitch.

Process doesn’t matter, once you get to a certain point. A point where your story sense already knows how a story is built from a foundation of universal principles of dramatic theory, structure and thematic power through characterization.

****

A little Storyfix news: the September issue of Writers Digest Magazine has an article I wrote; actually, it is an excerpt from my latest writing book. “Revive Your Story with Dramatic Tension” appears on page 58.

Also, Story Engineering was named as one of the “nine essential books for writers,” on Jon Morrow’s site, Smart Blogger, which has 500,000 subscribers. There’s also some interesting new 5-star reviews for the book on Amazon, if you’re interested in understanding why the book is among those nine.

The post The Passionate Cry of a Delusional Pantser appeared first on Storyfix.com.

July 9, 2016

Art Holcomb on: The Character/Plot Connection

(This is an excerpt from my July tele-seminar, “The 10 Steps to Building a Better Story” – more information at the end of the post –Art)

I’ll tie this all together at the end, so stay with me . . .

I want to begin with a story about growing up with my 10-year old brother Ray and his Hot Wheels tracks.

Ray loved Hot Wheels from the moment he first saw them. If you don’t remember, Hot Wheels was a system of cool replica cars and these road segments that you could configure all-which- ways to make more and more elaborate tracks. Click here to see them in all their glory.

Ray started out with just one set but kept adding more and more parts. He collected all the tracks from several different kits, borrowed pieces from his friends and went on to build more and more elaborates stunt track formations – loops, 90, 180, 270 degree turns. Twists and jumps. At some point, he went beyond the guidelines of the toy manufacturers and created lay-outs that no one had thought of.

Sometimes the cars would make it through to the end and he’d get so excited. Sometimes the cars flew off the track – maybe they were going too fast, or the turn was too steep and the car couldn’t handle – but he kept pushing the cars to do the most elaborate and interesting tricks.

The All-Important Test

And the way he tested these configurations was very simple. He had very basic criteria:

Did they make it to the end of the track?

Did the cars perform the way he wanted?

Was it exciting?

He pushed himself to make more unique and death-defying configurations. But the test was always the same. Could the car perform? Could the car make it all the way to the end, instead of spinning off of one of the loops or turns?

He spent hours designing configurations and then choosing just the right car for each.

Remember that.

The Truth about Plot

So – What is the true definition of a plot?

It is the mechanism by which the truth and humanity of a given character is delivered to the audience.

And in the argument of what is more important – Character or Plot – I believe that character wins every time

Why?

Because there are only a limited number of master plots and an assortment of variations;

But there are an infinite number of unique characters!

Each – both plot and character – are vitally necessary to the process fo storytelling.

The Job of the Audience

And what the difference between a plot that just relates a series of events and a story that is compelling to an audience?

It’s Audience Engagement

And the storyteller’s purpose? – To keep the audience doing their job – whch is, staying engaged in the story.

Engagement means that the audience must be made to work for their supper

Because a good story is not meant to be like syrup poured over pancakes – giving all the elements PRE-CHEWED to the reader or viewer.

The audience, in order to stay engaged, must be constantly longing to find out what happens next. So long as that’s going on, the story is working and you have them just where you want them – and more importantly, the Audience is just where THEY want to be.

You as the Imagineer!

Imagine a story like a roller coaster and you’re the designer.

Your job is to create the RIDE and everything is under your control. You decide everything: the length of the ride, the timing, length and details of every twists and turns.

Everything they see, hear, think and feel is completely under your control

Don’t think for a moment that Space Mountain at Disneyland – or any other roller coaster you’ve ever been on – is about anything other than the drama of the moment and your emotional reaction to it. You enjoy it because the designers did their job well.

It’s exactly the same with story.

To Wrap this Whole Thing up . . .

Let’s return to the story on my brother and his Hot Wheels.

This is exactly how I see writers and their plots in the best stories. Ray worked to get the most out of each part of his equipment. He pushed the limits of the track to get the best out of the cars. And he pushed the cars to get the best out of the track.

This is the nature of the all-important Character/Plot Connection

A Story is about the WHOLE of what you create

The plot is how we put the characters through their paces, show the extent of what they can do.

But it is through our characters that we illustrate to the world the truth and humanity of our lives.

Your stories are ultimately judged by the success of this interplay.

Because, as my young brother knew, you build the track to race the cars and you race the cars so that the crowds in the stands can feel the thrill.

It is as simple as that.

Goodnight, Ray . . .

* * * * *

IMPORTANT: I want to thank all of you who joined us in the DEFEAT PROCRASTINATION NOW teleseminar. We had over 300 StoryFix readers at the event and the reviews have been gratifying.

Thanks to you all!

In July, our seminar is entitled The 10 Steps to Building a Better Story, and we’ll be talking about how to make sure your story idea is strong enough to go the distance. If you’re interested in joining us, click HERE for more information – Art

The post Art Holcomb on: The Character/Plot Connection appeared first on Storyfix.com.

July 3, 2016

Addressing the Unanswerable Questions About Writing A Novel

(Apologies for my absence. I should have filled the gap with guest posts from my wonderful Storyfix partners, but I fumbled that as I focused on a new non-fiction project, which I am excited to share with you in a couple of weeks.

As for today’s post… I return with a bit of a rant. Forgive the blood coming out of my forehead on this one.)

I am quietly observant of several online forums composed of novelists-in-waiting, a few of them on LinkedIn, which publishes a list of “20 Essential Groups for New writers.” One of which is the focus of today’s post.

I could pick any of them to make my point today, because they are all basically the same.

This is where you get new writers telling other new writers what they should know.

What they should and should not do. Often with an authoritative context. Too often.

Like the guy who proudly announced, “I don’t plan my stories. That doesn’t work. It robs the entire process of creativity.”

Okay folks, now we know.

A few days ago a new writer posted a generalized plea for help – a very common context on these sites – that went something like this: “I’m writing my first novel, and I need to know how to start and what to write, and how to get it published.”

I know… right?

There were well over two dozen responses, from fellow new writers who seemed to know these answers. Here’s one of them:

Just start writing until you finish. Don’t stop to correct anything. Then go back and fix what needs fixing.

Over half of the comments echoed this.

Because this is what new writers believe. And say to each other.

Ah, the secret of the writing process, at last.

To which I quietly ask… how will this guy know what needs fixing, other than those typos?

Truth is, there is a time in the process for this crash-and-burn drafting, but it is definitely not the way to begin.

Here’s another perfectly normal question:

I have a captivating story and concept in my mind and have started working on writing chapters for the same, however, since I am a first time fiction author, could any of the experienced authors here share your thoughts on the things to consider while writing a fiction novel and also some enlightenment on approaching publishers at the end of this?

He’s writing a fiction novel.

This is all you need to know about the level of discourse on these forums.

As for my response – which I didn’t post; I never post on these things, I would spend half my day addressing 101-level issues — I would start with this: never, ever, as long as you breathing, refer to your book as a “fiction novel.” That’s like saying pasta spaghetti. Or winged airplane. Or singing vocalist. Yeah, there is something informally referred to as a non-fiction novel, but that’s the only time you need to lead with a qualifier.

Don’t sound like a rookie that is on Day 1 of the journey. Even if you are one.

The longest response among the 29 offered from the membership was about 75 words.

I have written 200,000 words on the subject over three #1 (Amazon niche) bestselling craft books, and over 1000 blog posts, many of which boil down addressing this and similar questions. What’s-the-meaning-of-life type questions. Because that’s what it takes to cover the scope of that arena.

My friends Art Holcomb and James Scott Bell and Randy Ingermanson and C.S. Lakin and K.M. Weiland and Jennifer Blanchard and many others have done the same.

And yet, to some extent this question remains unanswerable.

Many of those 29 responses were on point, including the one that suggested it was way too soon to be worrying about how you plan to publish. Which is counter to what someone else said in recommending the the self-publishing route.

Because of course, you can throw anything you want out there on that basis, the purest of utter crap if you desire, and good things will surely happen.

To which I say… the bar for success is no lower in self-published venues that it is at Random House. The very few monster self-published home runs that emerge – like The Martian – are every bit as good as what the Big 5 publishers put out, so that becomes the comparative standard.

I stay off the forums because I usually end up in a pissing match. Some new writers don’t want to hear anything that smacks of mentoring. Because this is high art, damn it, and suffering isn’t optional and there are no rules.

Watch the comments section here. They’ll show up, I promise.

The Craft-to-Art Gap

I’ve noticed something connected to this conversation among the reviews of my three writing books. Aside from the people that simply don’t like my writing – and there is a grouchy network of them, they attack me as if I’ve insulted their daughter on prom night – there are writers who claim I leave out the how.

I wrote an entire book on the how – Story Fix: Transform Your Novel from Broken to Brilliant. It is cover-to-cover about the how… and yet, some readers missed it.

Because it’s complicated.

Because you have to be able to wrap your head around it.

One guy assaulted me for using “big words.” Yeah, like premise and resolution and set-up and first plot point. Monster, M.I.T kind of words.

They miss it, because it isn’t math. It is story sense. Story sense is the sum of all the craft you can eat at the workshop buffet, digested on your terms.

Nelson Demille can tell you why his books are bestsellers. So can I: Because he taps into a patriotic context, and delivers a hero that is both witty, clever and courageous with high-stakes drama.

Michael Connelly can tell you why he’s the absolute king of the police procedural. Because we don’t just like Harry Bosch, we admire him, we want to be him. Connelly puts him into highly dangerous, empathetic situations, often connected to big real life issues, with emotionally-resonant stakes.

Another big word there: emotionally-resonant.

Oh, that’s it. So how do I DO that?

But how do you make it witty?

What does clever mean and how do I DO it?

What do you mean by context? You use that word over and over, I had to put the book down. You suck.

I tell people, here and in my books, to strive for a conceptually-driven premise. Along with that comes a clear differentiation between concept and premise.

More big words and crazy confusing ideas. Concept and premise are different? How can that be?

People ask me how to find a conceptually-driven-premise. Rather than studying the criteria for that, and the examples of that — which is precisely how you get there — they want the gold ring UPS’d to them.

You get to decide what is conceptual. You are stuck with… you. If you skip over the criteria and examples, that’s on you, too.

Or this 1-star review pearl: Larry is very confident that his system works where others fail, except that he really doesn’t know how to use the word physics. Hint: It’s not the plural of physic.

Maybe, after looking up the word physics (because it’s in the title of the book), he would understand that, despite the fact that I never once, not even with a typo, used the word “physic,” and that it is applied as a metaphoric reference to story forces.

A massive leap, that. Real Mensa stuff.

The bottom line is right there, in that sentence: understand.

Our entire journey through craft and the assault toward the summit along the learning curve, is simply to do that. To understand.

Because when you do understand, when you get that story sense is something that exceeds the sum of the craft parts that will lead you to it… only then will you be able to summon the inexplicable, unteachable and totally unique story sensibility that those famous authors command, and yet, cannot convey or explain any better than us lowly writing teachers who struggle to bring the word to the writing community…

… including the guy that doesn’t understand the word physics as he rails against me using it…

… including the guy who tells other writers to just sit down and write…

… including the guy who said in his review that I promise definitions but never deliver them… to which I responded that the definitions appear in little black boxes in the book, with the bolded word “Definition of…” in the subheader, and then I give the specific page numbers of those eleven key definitions… all of which was deleted by Amazon, which doesn’t want authors challenging clueless reviewers even when the response is merely the correction of faulty information.

Because the writer couldn’t wrap his head around it. Because this is supposed to be easy, to be fun. It’s just beginning, middle and end, right? What’s up with all those big words and principles and models?

James N. Frey said it best, right here on Storyfix a few years ago (click HERE to read that stellar post):

Writing is easy. Just sit down and bleed from the forehead until you get something that works.

Thing is, too many writers don’t understand what bleed means in that context. Because it is an analogy, and analogies require a leap of logic and interpretation that is above many.

Or what works means, because other than the criteria for what works – which is precisely what the Story Fix book is all about – nobody can tell you how to get there.

Story sense isn’t a gift, it is a muscle.

Analogy alert… put on your sound-retardant headphones and think.

Sure, some are born with stronger muscles than others, but anyone can increase their muscular size and strength to some degree. Through hard work. Though the application of proven principles.

But even then, you need to know what the work is, what those principles are, and what it all means.

And in writing, that ends up being a minority subculture within the masses who are online talking about it.

I can point you toward the craft.

Many writing teachers can do that. Pick your teacher, pick your approach, pick your story modeling.

But you absolutely cannot cherry pick the principles and criteria that apply. They are universal. They are complex yet learnable.

Once learned, you and your resultant story sense are on your own. And thus we have explained why those who write critically and commercially successful fiction are defined as a low single-digit percentage of the “just write” crowd.

But like that donkey that you can lead to water but you can’t make drink… nobody can make you get it.

The post Addressing the Unanswerable Questions About Writing A Novel appeared first on Storyfix.com.

June 5, 2016

Let Art Holcomb Fix Your Procrastination Problem

If you’ve been here a while, you know about Art Holcomb. Accomplished writer, teacher, and in my opinion, one of the brightest minds in the writing/mentoring game out there.

You also know me. Short of recommending books, I don’t do a lot of endorsing. I absolutely don’t do any affiliate promotional deals.

So today’s post isn’t so much an endorsement – which I would give to Art in a heartbeat – as it is the sharing of an opportunity to learn from one of the Masters, with a focus on the one thing most of us struggle with no matter how long we’ve been at it.

Read below to learn more about Art’s upcoming teleseminar (which launches June 20th), for which he’s graciously extended a discount to Storyfix readers. Here’s how it works, and it’s simple: email Art at aholcomb07@gmail.com, tell him you’re a Storyfix reader. He’ll arrange a (roughly) 25% discount on the fee for the teleseminar, down to $37.

As you’ll see below, the regular price will b e $79 after June 10th, so act now.

Also notice that this discount is actually greater than the one he’s offering for early enrollment elsewhere. It’s worth every penny of that regular $79 price, so this $47 deal is amazing. But you’ll need to mention Storyfix.com in your email to Art to land it.

Here’s Art’s own promotional announcement for this terrific opportunity.

*****

Here’s a truth of your life: You are not anywhere near where you REALLY want to be with your writing.

You know it.

I know it.

You are not putting in the time you need to make your work exception – and it bothers you because you do not know why.

Ask yourself: Am I getting my writing finished? Is there something that’s keeping me from the keyboard? Do I feel guilty sometimes because I’m not making the headway that I know I should be making with my writing?

What’s really holding me back ?

You’re not alone. I work with professional writers every day in my private practice – and they can have the same problem: the real world is constantly intruding on our lives. It’s hard to find the time or the peace and quiet and sometimes getting the words out and on to the page is like pulling teeth.

I’ve learned that truly everyone goes through this – and I mean EVERYONE – at some point in their life. I work with professional writers everyday who have faced these same struggles – writers whose income and livelihood DEPEND on their ability to produce . It can be one of the most serious hurdles any writer can face.

But it doesn’t have to be so hard.

There is a way out. A way that can make writing easier again – the way it was in the beginning.

What you need is a new approach to the work, a new way of looking at your talent and skills that can give you the confidence to move forward.

My career is built around helping professional writers succeed and I’ve helped over 300 professional screenwriters and novelists over my career get back on track. People who make a good living as writers. They can literally not afford to let fear and procrastination affect them – and neither can you.

The same techniques they use can help you too.

I’ve put together a teleseminar on eliminating procrastination and the fears that writers face. It’s entitled:PROCRASTINATION – How to Defeat it Forever!

In it, we’ll cover:

The Journey that every writer makes through their career.

Every possible reason that you may have to procrastinate – and a way to break through each of them.

How to make sure you’re able everyday to hit the ground running.

The truth about Writer’s Block and how to eliminate if from your life forever.

The three techniques professionals use to create quality work quickly.

The realityabout the fear you may be facing – what it really is and how you can turn it from problem to motivating asset.

Procrastination a real problem And it’s impossible to be a successful writer without facing this issue head on. I have shown my working screenwriters and novelists how to eliminate it from their lives – and I will show you how the very same techniques can work for you.

The seminar will be launched on June 20th and would normally be $79 – but for the next week, I’m making it available to you for just $47 – if you sign up by June 10th.

Here’s what some of my clients have said about the seminar.

“Art’s techniques got me from dreading my writing to making it the greatest thing I do all day. I finally got my novel finished and I’ll be able to do my next one in half the time. – Peter R.

“I was amazed! By just facing some truths and learning more about who I am as a writer, I found my output increase three fold. – Sheila B

“I didn’t think anything would get me back to my writing, I just couldn’t finish anything. But Art showed me where I had strayed of coarse and now my writing is getting finished and I’m starting new projects. Thanks so much, Art!” – Peter W.

The teleseminar can be available to you at anytime through your computer or phone – to listen to whenever you need the boost, And the special price of $47 means that you can get your writing back on track – you can feel the joy of writing once more – for less than the price of dinner out for two.

Signing up is easy – Just email me at aholcomb07@gmail.com that you want to join and I’ll send you all the details.

It’s a small price to pay to change the way you write forever.

Make a difference in your own life today. Become the writer you know you can be.

Take this small step into a much bigger world. Join us today.

The post Let Art Holcomb Fix Your Procrastination Problem appeared first on Storyfix.com.

May 26, 2016

A Deadly – and Perfectly Normal – Rookie Trap That Can Cost You Years on the Learning Curve

Important post today. With an attached tutorial that just might change who you are as a storyteller.

Don’t skim this one. Not ironically, that (skimming) is the very thing that can cost you years (or decades, I kid you not) of development time… when it is the craft itself that you are skimming and short-changing.

There’s a FREE GIFT here, too, it is a no-strings click away, if you get that far. If you don’t… then just maybe this post is about you. The irony is poignant… you miss the goodness because you skim and don’t absorb the core.

Also, after that (blogging principle #1: always deliver the good stuff, the free stuff, before you even mention your own projects or services; which, in this edition of Storyfix, is presented below… I hope you’ll have a look)… something very new and unexpected for me – and ridiculously exciting…

… with a cool “June Special” offer for those hoping for a solid story coaching opportunity.

One word on that: DISCOUNT.

But first… some really important stuff on craft.

*****

This is a true story. A case study in normalcy.

You don’t want to be a normal writer. Making normal rookie mistakes. Writing from the wrong set of beliefs, derived from the wrong interpretation of the wrong conventional wisdom.

Because so-called conventional wisdom may not be be serving you. It may not be wise at all.

Among the 90 percent of authors who don’t achieve even a fraction of their writing dream, the vast majority can attribute that heartbreak to the shortcomings of what they believe they know about what a good novel entails, and how to get it onto the page.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve challenged the so-called conventional wisdom, throwing back the curtain of clarity at workshops and in one-on-one coaching relationships, even here within these posts, resulting writers announcing what amounts to a Great Epiphany that changes the course of their writing destiny.

It happened this morning, in fact. Actually, the Epiphany part hasn’t arrived yet – the exposure of the need for one did – but I’m betting it will.

This is the kind of thing that makes writing teachers/coaches/guru-types crazy. Because we’ve put the truth right in front of them, and it goes unread, unheeded, or misunderstood. It can take several passes at it to finally grasp it with the detail required.

Today’s post seeks to cut the number of passes required before it finally sinks in. By giving that truth to you, straight up.

Notice how, perhaps, this tale parallels your own writing journey.

You have a story. You’ve outlined it, maybe you’re written a draft. You love it. You’re certain it has legs. Secretly, you believe it – and you – have the chops to not only get published, but to become a bestseller. You are next to certain it is that good.

Because the idea at it’s core absolutely fascinates and inhabits you. Heck, with that idea, the novel virtually writes itself.

Be honest. You’ve been there.

And so, because you are a diligent new writer, or an experienced writer who hasn’t lost the blush of the new writer, you decide to confirm the fact of your story’s greatness. You send it out there in some sort of beta form. Maybe to a story coach, to test the waters.

That’s where I come in. Because such a story, from such a writer, arrived in my inbox not long ago.

Here’s an important context to keep in mind: this writer is smart.

Really smart. With enough enthusiasm to fuel a Trump rally. With a pitch that virtually boils with confidence about the upside of the story. But the curious truth is… that very enthusiasm is what makes this writer blind to a level of understanding that is required before the story will work to the degree he/she believes it will.

It’s what makes them skim the textbook because they can’t wait to graduate. To get the good stuff. The stuff they believe they arelady understand.

But too often… don’t.

They believe the story is enough. They believe that craft itself is intuitive. Which it is, to only a certain extent.

It’s that less than certain extent that comes back to bite you.

To severe your connection to the potential that you believe in.

When someone signs up for any of my coaching levels – this one being the first-line Concept/Premise analysis – they receive a Welcome Letter that includes not only core content (definitions and examples) but deep tutorials (nine of then, in this case, resulting in a net delivery of an entire writing craft textbook or workshop; this, as much as my time, is the essence of the value delivered for the price).

Part of the content within that Welcome Letter is a clear definition of Concept – the thing you take for granted that you understand, but based on data, probably don’t, at least fully; thus, this becomes the opportunity at hand), including vivid examples… as well as an equally clear definition of Premise… with a discussion focusing on how and why they are different.

With those nine tutorials that go even deeper into this critical and empowering difference.

They get all this first. Before they are asked to submit everything.

And then comes the fatal moment.

The serpent’s temptation. The consequences of impatience. The fruit of hubris. The sad end-game of naivety. This is where…

… they skim the Welcome Letter. Or worse, more often, they don’t read it at all.

Hey, I get it. When I smash into a box containing a new toy – phone, flat screen, computer, mixing bowl, whatever…), I rarely consult the “user’s manual.” I mean, how hard can it be, right? The phone walks you through the setup, who wants to read about it first?

Thing is, writing a novel is orders of magnitude more complex, nuanced and challenging that getting a new toy online. It’s as complicated as: doing surgery… flying an airplane… healing a broken heart… inventing a new electronic device… designing a bridge or a building… I could go on for days. All of these examples, by the way, are from writers who do those things, and once on the other side of enlightenment confess that writing a novel is as hard as their day job.

Chew on that for a moment.

You think you know all you need to know? The odds say you don’t.

By skimming or not reading the very material that can make your story work, in the belief that you don’t need to know, or that you already do know (without that knowledge ever being tested or confirmed), you are doing nothing less than shooting yourself in the foot.

Or in the head, in this case.

Because… his story was nothing more than fine.

It was good, but not good enough. It was flawed in the very thing that the Welcome Letter focuses on.

The thing that separates bestsellers from the pack. Something that resides within that very idea… the one he thought already glowed in the dark.

This writer, because he is smart and not completely controlled by a belief that he knows more than the rest of us (that happens, too), responded very openly and professionally to the feedback that his concept was flat, while his premise was pretty good, though completely too familiar. That a stronger concept could, in fact, fuel his premise to a higher level, perhaps to a stellar level within his genre.

He got it.

A few days passed.

And then an email arrives this morning, confessing that he just doesn’t get the whole concept thing. What it is, why it is important, and how it relates to premise, without being premise. By the way he framed the question, he exposed what is an unavoidable truth:

He either didn’t read the Welcome Letter… he didn’t get it… he didn’t buy it… or he skimmed it and forgot it.

Which could explain the entire shortcoming of his story.

So rather than sell it to you… allow me to GIVE it to you.

So that you might be among the few who begin their stories with this massive advantage, which impacts and defines the very square-one moment of your story inception.

Read the Welcome Letter. You don’t need to buy a story coaching package. In fact, I’m not doing any more coaching until late June.

This is the stuff you need to know, to grasp, to fully understand.

A huge percentage of writers, even those who are well down the road, actually don’t understand this. But when you get it, you’ll see that this is the very thing that differentiates bestsellers from lesser books, the published from the non-published.

If and when you get this, you may no longer settle for – and indeed, are prematurely enthusiastic for – a story that is already flawed in the essence of what this document (and those nine links) clearly presents.

It’s not easy. Some folks read it and still don’t completely get it. Some never get it. But you have to read it first. You can’t merely skim it. You need to study it, to absorb it.

Then you will be a writer on the other side… among the few who do get it. Who are orders of magnitude ahead from the first page forward, because their original idea has turned into a conceptually-driven premise that meets all the criteria of greatness… instead of simply writing your idea without that level of empowerment.

Publishers and readers are not looking for the next also-ran, middle of the shelf novel. They are looking for home runs. This is what you need to understand to make that happen.

Read the Welcome Letter here — Quick-Hit WELCOME LETTER .

You’re welcome.

*****

A Story Coaching June Special

The Welcome Letter you’ve hopefully just downloaded is the first step in my Quick Hit Concept/Premise Analysis. The normal fee for this, including the Questionnaire and analysis/feedback that follows, is is $79.

Here’s the give and take of the special: the FIRST TWENTY takers can participate in this coaching level for only $50.

For this discounted service, delivery of my coaching feedback (two rounds; you get a chance to revise your first submission of responses to the Questionnaire, which will receive a second round of feedback or affirmation from my end) will occur before the end of June. Normally I try to respond within five days (something I’m working on), but for this special – the very reason for it – requires me to collect these twenty submissions, and then work on them in the second half of June.

Why? Keep reading, it’s because of the project described below.

If you want in, don’t use the normal Paypal buttons on the home page of Storyfix.

Rather, opt in by going to Paypal directly, and SEND the $50 discounted fee to me, at storyfixer@gmail.com. Upon receipt of the Paypal notice on my end, I’ll send you the Welcome Letter (the same one you get get for free, above) and the Questionnaire for this level.

Take all the time you want in responding… hopefully, you’ll use that time to immerse yourself into the specific craft of concept/premise delivered in the Welcome Letter and those nine tutorials it links to.

If you can wait a few weeks to hear back, you can score this discount, beginning right now. The first 20 writers to opt-in get the deal.

*****

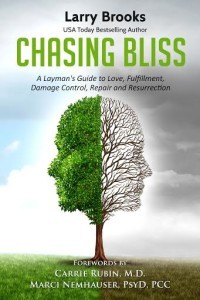

Announcing a new book, a pet project of mine:

Chasing Bliss: A Layman’s Guide to Love, Fulfillment, Damage Control, Repair and Resurrection

I’m building an email list for those interested in this. If you’d like to keep updated, send me an email (storyfixer@gmail.com), I’ll add you to the list.

The post A Deadly – and Perfectly Normal – Rookie Trap That Can Cost You Years on the Learning Curve appeared first on Storyfix.com.

May 15, 2016

A Free Reading Guide to Use with ‘Story Engineering’

(Quick pre-read note from Larry — Jennifer Blanchard represents the best possible outcome for me as a writing teacher, blogger and author. She’s someone who had looked for clarity for many years relative to how to write a novel – really write a novel – and when she found my website, and then my book, “Story Engineering,” she says it changed her life. To be honest, she’s not the only or the first person to say that, but she’s the absolute best living proof-statement to this day relative to how this understanding – not so much me personally – can truly empower your writing life. I’ve watched her blossom not only as an author and a professional, but as a purveyor of writing wisdom in her own right, with an on-going stream of helpful guides and ebooks and blog posts and guided programs that take the craft forward in clear and value-adding directions. A month ago I had the privilege of c0-presenting a 4.5 day “master class” workshop with her, and listening to her wax eloquent on the various facets of storytelling craft was an amazing thing to behold. She is one of the most prolific, positive, high energy writers I’ve ever met. Someone we should all listen to. It humbles me that she reflects on her work with me as she does here. Every writing teacher should be so blessed to have someone not only get it to the degree she gets it, but represent the material as she does. I am in her debt in so many ways. Larry)

Like so many of you reading this blog, I had my life totally changed by discovering Larry Brooks and his story structure model. For me, this was back in early 2009.

At the time I was on a mission to find the information I was missing, the information that would allow me to finally write a cohesive, engaging story (because up to that point everything I had tried was a total disaster).

Googling around and checking out articles, I somehow managed to come across a guest post by Larry on another blog. That guest post led me to StoryFix.com.

And the rest is history.

That article totally changed everything for me. It brought story structure front and center in my mind and helped me to see exactly why nothing had worked for me previously.

I was hooked.

Hooked on Larry. Hooked on story structure.

And since I had read every freaking writing book and took every freaking writing workshop and college class I could find about writing novels, and still never came across the story structure info I learned from Larry, in that moment I made it my mission to spread the story structure message far and wide.

So in late 2009, when Larry put together an eBook called: Story Structure: Demystified, and asked for beta readers, I jumped like a sugar addict jumps for a cupcake.

I got my hands on that eBook and I read it cover-to-cover. Five times in the same week. I even printed the whole thing out and put it into a binder so I’d be able to have a hard copy to read and make notes on. (And, of course, I wrote a glowing review.)

A year later, this amazing, life-changing eBook became, Story Engineering, published by Writer’s Digest Books. It remains one of their bestselling titles on writing craft, and was followed by two other killer writing books that build on that initial revelation.

I make it a point to re-read Story Engineering at least once a year (sometimes twice!). Because I want to stay connected with the core stuff required to write a killer story.

If you’ve read Story Engineering, you know what I’m talking about.

This book is by far the bible of storytelling. I recommend it to every single writer I come across. I shout from the rooftops why people need to read it and follow it.

Because it’s just that good (which you already know if you’ve read it).

The Story Engineering Study Guide

I wanted a way to keep the information from the book right in front of me at all times. Almost like Cliff Notes for Story Engineering.

So I created a reading guide to go with the book. It’s a simple PDF that I used to keep track of what I learned in each section, and any additional questions I had or things I needed to get clarification on.

And I’m gifting this reading guide to you, so you can also use it to keep the principles of storytelling at the front of your mind.

You can download the free Story Engineering reading guide here .

How has Story Engineering (and Larry Brooks) changed your life? I’d love to know! Share in the comments.

About the Author: Jennifer Blanchard is an author and story development coach who empowers emerging novelists to take control of their writing destinies, by helping them master craft and create a pro writer mindset. Grab her free Story Structure Cheat Sheet and put the principles of structure to work in your story. Visit her website here.

The post A Free Reading Guide to Use with ‘Story Engineering’ appeared first on Storyfix.com.

May 5, 2016

The Whole “Story Engineering” Enchilada Overview, via 20 PowerPoint Slides

Trying to teach the full enchilada comprehensive overview of the Story Engineering writing mindset in one hour – 50 minutes, to be more accurate – is like trying to equip a teenager for college, marriage and a corporate career during a quick lunch at Applebees.

As if one could actually keep the attention of a teenager for that span of time.

But that’s what happened to me in Las Vegas, at the Las Vegas Writers conference, and it’s all my fault. I was asked what I wanted to teach, and then this happened.

Not that the audience was composed of teenagers, quite the contrary, they were hungry for information. I use that analogy because… well, it makes the point. The writers in that room were for the most part mature, whip-smart writers seeking to go to the next level.

It seemed like a good idea at the time, and to some extent, it was.

A contextual overview of the broad span of the Story Engineering context is a valuable piece of the delivery, much like looking over a navigational map before setting out from Seattle for Hawaii in a sailboat. One should know what one might expect and not expect along the way.

Storms and sharks and running out of gas… all of that awaits on the story development journey, as well.

Perhaps the most frustrated person in that meeting room was me.

Because I know from experience that even a full weekend workshop leaves some of the sub-sets and nuances of this learning short-changed, relegated to a stud- this-later-when-you-have-more-time take away. The structural diagram, in particular, is a full day lecture and a full year or more of immersion (which includes actually applying it within a draft) to fully wrap one’s head around the functionality of it all.

Those seeking a magic pill or a quick fix always leave disappointed, even after that full weekend workshop.

And yet, the 50 writers in attendance (twice, over two identical sessions; some of the second day attendees were repeats from Day 1 who wanted more) seemed to hear and learn what I wanted them to see and learn, given the time constraint. I could almost hear their brains exploding, their eyes wide and their questions astute.

Of course, the long-form exploration of this resides in my three writing books, especially the first one (Story Engineering: The Six Core Competencies of Successful Writing, from Writers Digest Books), though the other two go beyond that introductory context to explore how these core competencies are empowered to work (“Story Physics”), and then how to be hands-on with them to either plan or revise a work-in-progress (“Story Fix”).

That excitement translated to what amounts to a writer’s dream come true (mine), when on the third day, just before my keynote address, they brought in 100 copies of the three titles (thanks to the local bookstore that stepped up to make this happen), which sold out in about 30 minutes or so.

Which is why I wanted to share this with you today on Storyfix.

If you’re been around here, this becomes a valuable review of the basics, with an integration of the core competencies and story physics, all within the context of application. If you’re new to this, then this becomes precisely what it was in that meeting room – a Cliff Notes crash course introduction into what many believe to be the most effective and clear story development and writing model out there.

Something that can truly change and empower your writing journey.

One final note here… I tried to get this onto the post page itself, which was a no-go, thanks to whatever constrictions WordPress decided to impart to the software.

Greek to me.

So you can use this link to gain access to that PowerPoint itself; I hope you will:

Bon appetite. Epiphanies may await. I hope you find one or two here.

The post The Whole “Story Engineering” Enchilada Overview, via 20 PowerPoint Slides appeared first on Storyfix.com.

April 10, 2016

The Key to Criteria-Driven Story Development

Two Things You Should Know About Your Story… the Earlier the Better

Today’s post could easily break down into three or four meaty posts about writing a novel or screenplay that works. I mean, really works. But none of those points are contextually complete without the others, they reside in the writer’s tool box as a merged whole, a set of principles that are truly a sum in excess of the parts.

So get ready to consider the whole storytelling enchilada, from the first bite.

Already some organic writers are heading for the delete key. Because the mere suggestion of “criteria” in the context of story development runs against the grain of that particular end of the continuum. Which is a shame (and also the cause of much frustration and career-stalling), because if you leave now you’ll miss something that might change everything about reaching your writing goals.

The key to wrapping your head around any gap between “pantsing” a story (looking for the best version of the story while you are writing it) and “planning” a story (having a front-to-back vision for how the story will unspool prior to writing a draft; both of these define opposite ends of the aforementioned continuum, which in reality summons most writers to somewhere in the middle) depends on your understanding these statements:

Both are just processes.

Each is a means toward an end. The same end.

Both can and do work. Neither, when done properly and completely, is easier or results in a better story than the other.

The more advanced a writer is, the more planning they do, even if it resides in their head only.

Once you reach the “final draft” stage, how you got there no longer matters. Process has no place in the conversation about what ultimately makes a story work.

And this, the most important statement of all: Once you have what you believe to be a final draft, any assessment as to how well it works are nothing other than criteria. Which by definition demands that a writer understand these criteria, and aims for them, as they develop their stories.

Any blog post or book that claims to tell you how to write is always in context to this point, which is often implied, frequently minimized or sometimes omitted altogether. For example, the guy who tells you that “story trumps structure” actually advocates for a particular process, certainly the one that works for him. Risky, if that process doesn’t work for you. And in either case, totally irrelevant if the process itself doesn’t end up honoring the criteria that makes a story work. (For the record, that book actually does come full circle back to the criteria for a good story, which sort of blasts the title into the cheap seats, while saving the intention of it.)

Or not. If, in the organic or planning process, the story ends up being weak on these criteria-based essences and elements.

Before a story can work, a premise needs to have emerged to the narrative development process.

If you start your draft before you have a premise – even if you have great characters, a vicarious setting and weighty themes – you have just christened your draft an exercise in searching for the story.

That’s what process is, and all that process is: your search for story. Which, again, is best done when the criteria for the story you end up with actually drives your decision to land on it. From there, the development of story unfolds in contexts to similar criteria, broken down into elements of expositional pacing, dramatic escalation, character arc and resolution… all of which is structural in nature.

If you start a draft that is in context to a premise that is firmly on the table – meaning it is not just “a” premise, but rather, the best possible premise, as defined by the criteria – then you are testing, expanding, enhancing and validating that story during the development process (again, either organically or planned). Which, in a functional process, may result in revising not only the ensuing draft, but the very premise that drives it.

The mistake, the common misstep, that shoves many stories off the cliff is this: the writer accepts the first premise that comes to mind as inspired by the original idea. They don’t hold it up to the light of analysis that juxtaposes it against criteria that always apply and always serve the goal of a more effective story, no matter what the process is.

In other words, a weak premise will yield a weak story. Even when it is well-written and is populated with richly drawn characters.

The goal for process is to render it compelling.

Which breaks down into criteria for effectiveness:

Is the premise a landscape for something dramatic? How dramatic? Could it be made more dramatic? In genre fiction, the more dramatic, the better.

Is the premise rich with thematic relevance? What buttons does it push? Why will anyone care about this story?

Does the premise offer an intriguing story world (setting, both time and place, as well as culturally and sociologically), with an inviting context framing a hero’s quest? What will the reader’s vicarious experience be?

Does the premise give your hero something worthwhile to do, driven by stakes that motivate, rendered dramatic by antagonism that challenges?

Is your story about something… rater than about something happening?

Which, turned inside out… Or is your premise merely the story world itself, or a character him/herself, without giving your protagonist something inherently dramatic and challenging and important and empathetic to pursue and achieve?

If your answer to this last one is yes, then these criteria have served you, if you let them, because they show what may be lacking. Because if your answer is yes, your story is already at risk.

The mistake, in that case, is to actually write that story without – or before – working to enrich the premise itself, so that it more closely aligns with these premise-specific criteria.

These are criteria, at first, for the premise.

Once you begin your draft, these same criteria kick in to apply to the entire story arc – the manuscript itself.

Which is to say, if your premise doesn’t reach for these bars, your manuscript will likely fall short of them.

It is extremely difficult, often impossible, to launch a draft that will enrich or fix a premise that is inherently weak in these criteria… unless the draft evolves (changes) the premise. Such as draft thrusts you back into the search-for-story phase, simply by causing you to realize that your premise is weak.

Which occurs both for pantsed or planned drafts. Your process won’t take you there, it won’t save you, if you proceed without honoring the criteria. Which is why I contend that, once you reach the finish line, your process no longer matters.

But it does matter if you rely on the process to somehow empower your story to meet the criteria. It won’t. Only the state of your current story sensibility will do that, and at all points on the process continuum.

Memorizing the criteria isn’t enough.

Rather, you need to internalize them as the basis – the goals – for the work itself. In the way a doctor or pharmacist honors biochemistry. Or the way an architect or engineer honors the principles of stress-dependent design. These principles work when this is how you work, rather than some A-B-C thing you can’t readily apply to your first story idea. or worse, something you leave to chance in the naive idea that your idea is so strong that all the criteria will be met simply by getting it down on paper.

I just experienced this at a five-day monster “master class” workshop, preaching this gospel to 30 hungry and wide-open (process-wise) writers who never once pushed back on any of it. But then, when they were given the opportunity to pitch their stories, a few seemed to not have heard or understood a thing. Their premises were episodic, without a dramatic core arc. Their ideas were highly specific and less than resonant. In four-plus days of hearing the what and why of the principle-based criteria for an effective story, they never recognized that the story they arrived with was short of that standard.

Some of them at least. A minority, in fact. Others pitched ideas that did indeed honor the criteria for a premise and a compelling, dramatic story that spins from it. Some acknowledged that their story was indeed different after applying the criteria, which means their story sense had just escalated up the learning curve significantly.

The point: you can easily be so enamored with and seduced by your story idea – a story world, a theme, a character – and then the premise that springs from it (which of course is a given; if one writes a draft from an idea only, without having culled a premise from it, that is like beginning a race a mile behind the starting line) – to an extent that you fail to recognize any thinness in the way that idea aligns with the criteria, or even whether it is compelling and commercially viable at all.

It is rare when any idea emerges as a fully-formed premise.

An idea is not a premise.

An idea is a seed that you must develop into a premise, one that meets the criteria presented here. Because an idea is, in most instances, only a story world or a theme or a character, or even a dramatic proposition, and as such it is, by definition, incomplete. It is on you, the author, to deepen and broaden your idea into a premise, which requires a working knowledge of what a premise is, and what it isn’t.

So what IS a premise?

Something that presents a dramatic proposition, that opens a dramatic path for your hero to take. One that leads to a core dramatic arc, which become the spine of the unspooling narrative itself. From this spine we show character and theme and subplot and subtext and all the other little bells and whistles of storytelling.

But without a core dramatic arc, you are left with several stacks of narrative focus, not of it connecting to and empowered by a dramatic question that gives the reader something to root for, rather than simply something to observe and marvel at.

The Two Things You Need to Solidify Before A Story Will Work

These being a more concise summary of the above:

You need a compelling premise – not just a flat or familiar or random or remote premise – that becomes a rich story stage or landscape or framing device.

You need a cohesive, structurally-viable dramatic arc that is the narrative realization of that premise.

Because the dramatic arc IS the story. Everything – and I mean everything in the manuscript – hangs form it.

*****

A Tele-seminar from our friend, Art Holcomb.

You know Art Holcomb. He’s the maestro of storytelling, using the principles of story to teach screenwriters and novelists how to go deep, how to capture and harness the power of a compelling premise, and even how to optimize your process of doing so.

This tele-seminar, held on April 12th (6 pm Pacific), is entitled: “How To Be A Successful Writer in the 21st Century.” A big picture perspective that just might escalate your story sensibility in unexpected ways.

Oh, almost forgot to mention… this tele-seminar is FREE.

Click HERE to learn more, to sign up, and to visit Art’s awesome site.

The post The Key to Criteria-Driven Story Development appeared first on Storyfix.com.

March 22, 2016

Art Holcomb on… The Nature of Talent

A guest post by Art Holcomb

Let me tell you a story . . .

I had my first public success as a writer when I was 13. I wrote a play as part of a six grade class competition that — against all conceivable odds — went on to be professionally produced at a theater in San Francisco in 1968.

It ran for 6 weeks.

A play. Written by a sixth grader.

What a wonderful feeling – perhaps the greatest feeling of my life to date. And I learned an important lesson about myself that day – which was that I could create!

In the years that followed, I came to live for that rush, for the fire I felt.

Sadly, as a result, I became quite prideful, and even a bit stuck up. Because I discovered that I had TALENT! I believed that I could do something that few others could do.

And so it has for many years. I wrote and published and was convinced that I was a star.

But then a day came in college when I called upon that talent to get me through… and it failed me. I came up empty – literally – and thought I was done for sure.

I felt like that, lost in an ever-increasing dry spell . . .

. . . that lasted for 11 years.

After trying everything I could to create again, I reached out to someone who was to be my first writing mentor – famed science fiction writer David Gerrold.

I was so desperate that I drove over 120 miles once a week just to attend a class with David.

The weeks that followed were like torture – watching other students thrive while I still struggled to even one well-written sentence together.

At some point, David took me aside and we talked frankly about what was going on. As a result, he soon had me start doing the work: setting deadlines, shouldering my way through my daily pages and disciplining myself to produce work on a regular schedule.

Eventually, my productivity and quality came back and I got back in touch with my abilities once I realized that creativity works best in harness and under the thumb of a good work ethic.

I realized that I was able to change my life – once I stopped believing that my talent controlled my destiny.

And I learned the real truth about that TALENT:

What was once a source of great joy and power had, in fact, done exactly what the universe intended for it to do – give me just a glimpse of what it was like to be a producing artist – to be the writer I could become.

Because talent only gives you the taste of that fire, the rarest preview of all the things that could be. It tells the lucky recipient of a future lying just beyond the horizon.

But the truth is – that future lies ahead for anyone willing to fight for it. Because talent never lasts.

It was a long hard battle for me to reach that sense of fire and joy once more. To be able to PRODUCE and to CREATE.

I never took it for granted again.

I never again mistook my skill for my talent.

I am here today to do perhaps what no one else has ever done for you. To tell you what I know to be absolutely true.

That, for each person willing to do the work, there is a fire that can live forever inside of you. A fire to create, which warms the soul and ignites the imagination. My life would be hollow without it and I am grateful every day that I get to write and create and weave stories that can move friends and strangers alike.

So — enjoy your talent — but always see it for what it is: just a taste of the fire. And know that you cannot depend upon it forever.

Know that a lifetime of joy from writing comes from a lifetime of struggle and dedication, and that – if you do the work every day – the universe will reveal itself to you as you reveal yourself to it.

So – keep writing. Keep going deep into yourself. Demand more from yourself at every turn.

Because what is waiting for you just beyond that horizon – will amaze you.

(Larry’s comment: Amen.)

ART HOLCOMB is an accomplished writer, Hollywood script/story advisor and well-known writing teacher, as well as a frequent contributor to Storyfix.com. Check out his website HERE.

*****

Art was recently interviewed by Creative Screenwriting Magazine, where he is a frequent contributor. It’s a great look at the man and his contribution to the writing conversation, which includes a long-running contribution to this website and to it’s creator… check it out HERE.

*****

Storyfix was recently named by Angela Han’s website, Global English Editing (www.geediting.com), to their list of “The 120 Most Helpful Websites for Writers in 2016,” placed at #2 in the “Helpful Tips on Writing” category (out of 19 named, and ahead of some of the monster sites you’re familiar with). Click HERE to check it out.

They also have a helpful roster of the “55 Most Helpful Apps for Writers.”

*****

If you haven’t done it yet, check out my upcoming Mega/Master 4 day writing workshop, co-presenting with Jennifer Blanchard in Portland, OR, April 3 -7. Go HERE for more information, or click on the ad in the left column. There’s still room, and we’ll even feed you. But fair warning: be prepared to go deep, where your darkest fears and wildest writing dreams dance to music you may not yet understand… but after this, you will.

The post Art Holcomb on… The Nature of Talent appeared first on Storyfix.com.

March 9, 2016

Part 7… of a 101-level Series on the Basics of Story

Register now for a FREE tele-seminar on March 16, on Story Structure.\ Details await at the end of today’s post on Pinch Points.

(As an introductory tutorial, go HERE to read my guest post on Writetodone.com on basic story engineering. But please come back to learn more about a highly effective secret weapon in the war against reader apathy and waning dramatic tension.)

An Introduction to Pinch Points

Story structure exists to help us keep our narrative sequence on track, relative to exposition and pace. All four quartiles of a well-executed story have specific contextual missions that imbue each scene within them with just the right focus, avoiding the story-killing tendency to ramble or jump the gun relative to your hero’s proactive confrontation with the core dramatic issue.

Two of those specific quartile-empowering contexts — Part 2 and Part 3 — get a little help with a specific narrative moment that brings the story’s core dramatic focus back to the forefront – called a Pinch Point.

The pinch point resides in the exact middle of its assigned quartile, one each for Parts 2 and 3. The reason why, like much of story structure itself, connects to other aspects of how a story should unfold.

Let’s look at Part 2 to better understand this.

The context of every scene in your Part 2 quartile is showing your hero responding to a new story path, in the presence of pressure, threat, danger or opportunity, which was put into play – as the primary focus of everything – at the First Plot Point. Which was, as you should know, the transition moment from the Part 1 setup and the Part 2 hero’s response to the First Plot Point twist (new information that enters the story at that point).

With this focus on the hero’s response, it would be easy to actually push the source of the story’s conflict, the core dramatic element, toward the background. Which is not good.

Let’s say your story is about a family running from a bear, which appears at the First Plot Point to disrupt the family outing and is now chasing them through the forest. Very tense, right? But you have to do more than show us the family running away.

You have to show us the bear, as well.

Within the quartile mission being showing the hero’s response, we need a time and place to remind the reader of the source of antagonism (the bear, in our example). The Part 2 Pinch Point does just that, literally putting the focus back on the source of antagonism (the bear) to remind us of the proximity and threat of the danger at hand.

The hero hasn’t forgotten about that – he’s running from the bear, after all — but the reader might have, so we need to get the villain back into the game.

But what if there’s no bear, you ask.

No villain at all. What if my story is driven by a horrible disease or an approaching storm? Same thing, each of those is the source of the story’s antagonism and threat, which creates drama and conflict in the story. The Pinch Point functions exactly the same… show us the disease and its power to destroy lives, or show us the storm and the violence that approaches.

In Part 3, also in the precise middle of the quartile, you need to show us the villain (source of antagonism) once again. Yes, you can show it to us as much as you like in other places, which means you use the Pinch Points to show the antagonism in an evolved, much closer proximity, which in turn heightens drama in doing so.

Pinch Points become a secret weapon in the war to win the reader’s emotional engagement.

Why? Because fiction is based on conflict that causes drama, and these two structural milestones give that drama it’s moment back on center stage. In the case of the Part 2 Pinch Point, it might even be the reader’s first glimpse of what threatens the story’s hero.

Join us in Portland, OR, April 3 -7, for a massively intense and interactive workshop that brings all of these structural and character-driven story essences together into one cohesive story plan, regardless of your story development process.

*****

Free Teleconference Workshop on Story Structure!

Join story coach Jennifer Blanchard and me for a lively hour of discussion on the critical realm of story structure, including how it applies with flexibility to any story, every time.