Larry Brooks's Blog, page 13

January 1, 2016

The “Why?” Behind the Inevitability of Story Structure

I love a good challenge.

Almost as much as I disdain a misunderstood debate, the kind in which one party can’t get outside of themselves long enough to see that they’re already arguing for the opposition.

Last year I did a post for the Writers Digest website, explaining why (my opinion) “just write” is among the most dangerous soundbytes of writing advice ever uttered. It’s like telling someone about to on trial without a lawyer (an apropos analogy to trying to write a story without knowing how to write a novel) to skip law school and “just talk.” One reader commented in response that, because after years of practice some writers can indeed “just write” and be successful… I thank her for helping make my point.

There is a huge, hard-won backlog of knowledge and principle that makes anything that can otherwise be “made up as you go along” functional, if not downright fatal.

“Just do it” can get you killed, and it can kill your story, as well.

In that context, I’ve yet to encounter a writer who can disprove the existence or need for a largely given structure – the order and context for how a story should flow – for the rendering of long form storytelling.

Even the most famous names in the vast pantheon of pantsers, wailing their outrage at the suggestion that certain things within a well-told story tend to happen in a certain order – Stephen King, Diana Gabaldon, some dude who wrote a book called Story Trumps Structure, and countless thousands of unpublished authors who don’t want to lean in toward doing something the seems to dictate order in what they hoped would become the transcription of a muse, or worse, a character actually speaking directly to them…

… they all end up doing it. Executing structure in their own stories, or proving its necessity via the failure to find an agent or a publisher (or, in the new low-bar world of the self-published, readers themselves).

Stephen King’s and Diana Gabaldon’s stories aren’t successful because they are pantsers. They are successful because, at the end of the day their stories do demonstrate structure, as predictable and aligned as those of the most ardent and vocal advocates of structure (James Scott Bell, for example).

In a good story, the reader will have no idea, none at all, whether the author planned or pantsed, or believes in story structure or not. Because if the story works, structure will be there, and in a form that aligns with the universal principles that explain how and why they work.

A closer look reveals the so-called debate isn’t that at all.

Because those who decry structure as either limiting, evil, low-rent or some sort of imitation of authentic storytelling… they are actually talking about their preference for a certain story development process. One that allows free-form thinking prior to the application of structural principles and optimization, in contrast to others (and there are just as many successful names here, as well) who create from same those principles.

Structure is not how you write a story. Go about it any way that works for you, and call it whatever you’d like.

Rather, structure is what makes the thing work, when it finally does work.

Because when it does finally work – however you got there, via a one-draft manuscript-from-an-outline or 22 pantsed drafts written in the blood of your first born – it will have structure across the arc of the narrative.

Structure is precisely what the panster is looking for along the way.

Don’t take my word for it. See what a so-called “artist” has to say on this topic.

A writer on TheAtlantic.com takes a fuzzy swing at bringing clarity to this discussion, and you may feel as I did that he succeeds only in muddying the water itself with his own hope that structure is after all a cheap date with shallowness that is dashed upon the realization that it turns out, also after all, to be the glorious manifestation of universal truth and physics.

Give it a read.

And then come back here… because he throws down a challenge that I hereby accept.

He claims that across the vast oeuvre of writing how-to, “nobody” has addressed the question, relative to structure… of why?

To which I say… oh contrare.

I am that “nobody.”

I guess this guy hasn’t read any of my three writing books – all of which have been #1 Amazon bestsellers in one or more of the many writing niche categories – or visited us here on Storyfix.com. He even, in his own reluctant resolution that structure is a non-negotiable given – again, it’s not a process, it is the target and the desired outcome of any process that works – with the use of a word that I believe I was the first to apply to this craft, in this context: story physics (the title of my second writing book).

You want why? I’ll tell you why.

Before a story will work – any story in any genre – a reader needs to feel some sense of curiosity and empathy for a protagonist. That’s the primary mission and function of the Part 1 quartile chapters or scenes (in a novel or a screenplay)… this is where the story is setup in both character and dramatic contexts.

Both of those contexts are necessary for a story to work. That, too, explains the presence of a largely universal structural paradigm, because that framework accommodates and optimizes both. It’s a tall order, which is why attempting to fill it without a solid handle on structure – something the nay-sayers seem to be suggesting – is like trying to develop a medicine without any training or notions about biochemistry.

A story that is simply a static immersion into a time and/or a place, a narrative 3-D postcard that dives deeply into geography and architecture as deeply as it does the backstories and physchological depths of the characters who are simply sitting there walking around among it all… that’s a story that doesn’t work.

I’ve met way more people people who couldn’t finish a Jonathan Franzan novel than those who could.

A story doesn’t work until something dramatic is proposed.

A good story isn’t just about something – a time or a place or a culture or an issue or a theme – with the primary purpose of putting the reader inside of it all. That’s journalism, not fiction. That’s MFA stuff, and it doesn’t get published (ask an MFA grad, you’ll see).

Rather… a good story is about something HAPPENING within the context and framework of such a vividly-drawn story landscape.

When what is happening is up for grabs, with stakes and risk and consequences that readers can relate to… then it becomes dramatic.

Structure facilitates and accomplishes this, in a certain order and at a certain pace, whether the writer wants to call it that, or not. Even if they get there by instinct, or not (it’s still structure if/when they do get there, by whatever means). By definition, the very “set-up” context of the first quartile leads to something happening – that’s precisely what has been set-up.

Can it be done on instinct? Sure. It happens. Should it happen only by instinct? That’s the wrong question. Because this is also what happens – or more clearly, what doesn’t happen – in the vast majority of manuscripts that don’t work. Mentors who urge writers to just sit down and wing it, forget about structure and everything else… “be like me, because that’s how I do it” – are engaging in a risky game of masturbatory hubris, masked beneath the smugness of false humility that suggests you can do what they do.

Right. You, too, can do what Stephen King does. Good luck with that.

If you’re tired to beating your head against that wall, story structure is ready with a wake-up call.

There’s a time and a place for the writer’s instinct within any process.

In every good story there comes a moment when everything changes.

It’s called The First Plot Point, among other descriptors (such as “doorway of no return” 0r “the jumping off moment,” etc.) If it happens too early then the setup itself may be compromised. Emotional resonance is a high bar if you fully launch the core dramatic thrust of a story in the first 20 to 30 pages, and if it happens too late then the reader might literally bail on the story… because nothing much worth sticking around for is actually happening. We can only visualize so many falling leaves and the crisp cut of a gentleman’s cuff for so long before we toss the book aside and turn on Jimmy Kimmel instead.

Both choices make is easier to fall asleep.

The First Plot Point, when you truly master it as a narrative tool, is virtually without restriction.

It is the very antithesis of formula. because the manner and degree with which you thrust the story down a darker or steeper dramatic path is an infinitely wide road, yet one that demands a clear change of pace and direction. This is where motivation and stakes collide for the first time, or at least with such a resounding thud, after dozens of pages of strategic setup have brought the reader – heart and mind – to this moment of embarkation.

So what happens then? Structure tells us.

Writers who don’t listen, or can’t speak the language, are left only to guess. And when they guess properly, that is not the antithesis of structure, but rather, the validation of one’s story sensibility, which is itself a manifestation of structure on an instinctual level.

The more a writer understands structure, the more instinctual it becomes. Only when a writer gets to such a point does “story trump structure,” in the same way that an athlete’s gut instinct trumps the lines on the playing field. Which are always there, by the way, in virtually any game you can name.

Story never trumps structure. That’s like saying health trumps medicine.

Story IS structure.

With a fresh journey underway thanks to the First Plot Point, fueled with reader empathy and curiosity and emotional resonance thanks to a newly elevated sense of need and stakes and fear and opportunity (all of it nothing other than character motivation), we now need to accompany our hero and other characters on a journey of response to this new direction and its richer context.

That’s the second quartile, a Part 2 “response” context. Which, in classic three-act structure, is the first of “Act II;” because Act II has two equal halves, the entire arc of the story becomes, by definition, a four-part sequence, though shifting the language toward this level of specificity and accuracy – something I’ve tried to do in my work – is like trying to talk our electorate out of a two-party paradigm, even though both parts have a left, middle and right component, which becomes, in truth, a six-part demography.

An effective story changes in the middle. Every time.

That’s not formula, that’s physics.

Here’s why.

If the story doesn’t offer a shift in the middle then chances are it won’t work as well. That’s why we have a principle of structure that defines not only placement of this mid-story shift, but the nature of it — the curtain of awareness raises for either the hero, the reader, or both, by exposing truths heretofore hidden or masked or only partially assumed before.

Why? Because pace will accelerate as a result. A good thing.

That’s why.

With a new, clearly context of awareness in place for your hero after this midpoint reveal, your hero will find new or heightened need and motivation, often in the form of closer proximity or necessity relative to some sort of proactive confrontation or strategy with the story’s antagonist (a role that absolutely needs to be filled in a story, usually by a villainous player but sometimes in the form of conditions – storms, illness, cultural roadblocks, etc. – or psychological incapacitation).

That’s why there is a Part 3 quartile (the second half of Act II) with a context of confrontation. Because the reader needs to move closer, through the decisions and actions of your hero, toward a forthcoming resolution, which may or may not be clearly obvious.

There are no rules here. Only shifting contexts and an evolving flow.

That’s why it’s not formula, but rather, why structure is empowerment and optimization. Without it pace lags or exposition becomes random. Without structure the hero remains stuck and separated from hope. Without it resolution cannot ride a wave of evolving reader emotional engagement, which is how stories work best.

The story changes again in a new shift or exposure in what is called The Second Plot Point.

This is truly a point of no return, more-so that the First Plot Point, because the hero is either swept toward an inevitable confrontation leading to resolution, or chooses it. Either way, because this structure has facilitated an escalating level of reader engagement, we are there for every moment of an ultimate denouement, one in which the stakes fall as they will… all at the author’s behest.

Here’s one final, sobering truth about structure.

It doesn’t assure you of anything. You can do it all byk the book and your story still might not work all that well. Structure is the fulfillment of ideas, not the ideas themselves, which is why it defies cynicism. Structure is like an instrument, or like a blueprint – it is the creator’s fresh take and voice, the sense of specific timing and illumination, executed with passion and an eye for vicarious detail, that makes a story soar.

But like anything that seeks to soar, you must have wings to take you there.

Structure gives us those wings. Without wings, there is no flight. There is no story.

And in nature, wings are the very epitome of structure.

That’s WHY structure exists, and why we need to pay attention.

It is also why some writers can execute a story perfectly with giving it a second thought, or acknowledging it afterwards – because structure is sensibility.

Every argument to the contrary is either a misinformed feint toward process, or a submission to the sweet bliss ignorance.

Without it, you may never know what you’re up against.

*****

Join me here on Storyfix.com for a 2016 focus on deep craft, challenging truths and fuel for your writing dream.

The post The “Why?” Behind the Inevitability of Story Structure appeared first on Storyfix.com.

December 23, 2015

Redux: “Get Out of Your Own Way” – a Guest Post by Art Holcomb

Apologies for yesterday’s technical problem, which sent this to you with only a headline and no context. Thanks to Joel Canfield for the quick fix. Anything by Art Holcomb is worth a second try… so here you are. Enjoy.

Larry

********

“An exhaled breath must be cast away before you can take another.”

-Thulani Jengo

Years ago, a friend of mine was writing a mystery about a famous abandoned house in Northern California. David had teased me with this book for a very long time and after much cajoling and nagging on my part, he agreed to let me read it.

He finally showed it to me at a party over the Christmas break from college. He sat me down in his spare bedroom, handed me this beautiful leather binder, thick with each chapter tabbed and labeled, and then quietly left.

I was in for a treat. I held my breath for a moment.

And I read . . .

And, as I read, I grew even more excited. The first chapter was good, opened well, excellent visuals, with pacing and language that was capable and accessible. And I loved the characters.

The first chapter had been 34 pages long and absolutely left me hungry for more.

I flipped the tab marked CHAPTER TWO over and . . .

Blank paper.

Twenty blank pieces of typing paper.

I went through the rest of the binder and it was the same thing: 18 more tabbed sections of blank white typing paper.

About which point, David couldn’t wait any more.

He came in and nonchalantly asked how I liked the story:

ME: I love it! Where’s the rest?

DAVID: Well, that’s all there is so far.

ME: I thought you’d been at this for a while.

DAVID (proudly)I have been. I’ve been rewriting the first chapter until I got it right.

ME: For how long?

DAVID: Eleven years this February.

I couldn’t believe it. I was startled at first and then I experienced something that surprised me:

I started to get angry.

I’ve been helping writers achieve their goals for a long time. And I wasn’t upset that David had been working on a story for eleven years; I, in fact, had several ideas that I’d been working on since I was in high school that I was never able to get out of me. But eleven years on the same chapter, writing it over and over again, refining, polishing, rewriting, perfecting? This was less a labor of love and more like Sisyphus pushing that boulder uphill.

At this rate, David was scheduled to complete his Great American Novel 54 years after his death . . . assuming he got past the first chapter.

At this rate, David was absolutely doomed to failure. This was a squandering of what I saw as a real and special talent and it upset me.

We talked about this for hours that night, but I was never able to get him to see that this was less a novel and more a delicious sort of penitence. That unless he let that chapter go and moved on, this wonderful story would be relegated to that binder forever. That he was paralyzed by a real fear which lay just beyond the tab marking CHAPTER TWO.

David and I grew apart in the years that followed and, in that time, I met a number of people like him, who were caught in a loop, unable to take a step out of their comfort zone.

I’ve often wondered what separates the Davids of the world from the writers who go on to have long careers and satisfying relationships with their talents?

In the end, I think it comes down the combination of FAITH and TRUST.

FAITH that you have more than one idea in you, that you don’t have to be defined by a single effort, that your next chapter can be better than your last.

And TRUST in the breadth and width of your own talent, and that not only can you see yourself completing that novel but that it will be just one part in a great body of work . . .

And, most of all, Trust and Faith that you will have an audience out there.

In the end, regardless of how any single effort comes out, you have to be able to let it go when finished . . .

And take that next breath.

Success always lies in the difference between what a person can do and what that person WILL DO!

And the absolute truth is – I know you can do it. If you’re stuck, reach out to an expert like Larry and get some help from someone who has faced this before you. You’ll find that, with help, you can quickly find your way back to the road to success.

Make your talent count for something. Work hard. Dig deep.

And then . . . move on to the next challenge.

ART HOLCOMB is a writer and writing teacher. He and acclaimed novelist Steven Barnes have developed a system to get your writing on the fast track and get you producing great stories every year. Drop them an email at aholcomb07@gmail.com to find out more about their upcoming webinar for new writers in January 2016.

*****

Still running two year-end story coaching discounts, one of offering a $900 savings… both described in the preceding post.

*****

I want to share this paragraph from an email I sent to a coaching client today. He’s a terrific writer with a monster story on his hands (and, he’s very coachable), one that he and I are wrestling to the ground with an iterative process of pitch, breakdown, feedback, revision and more feedback.

I hope you find value in this:

This is the reason stories get rejected: the author whips it all into a stew of a story, and they fall in love with it. With the very notion of it. And then, under critical eyes, they explain and defend, and when the critic doesn’t seem to shut up, they rationalize that the critic just doesn’t get it, or – and this is worse – that the criticism doesn’t matter. First time authors, in particular, are well served to really listen and be open to change, when change is indeed called for in the spirit of making the story stronger.

The post Redux: “Get Out of Your Own Way” – a Guest Post by Art Holcomb appeared first on Storyfix.com.

December 2, 2015

Year-End Story Coaching Discounts

It’s a cash flow thing.

My story coaching business and speaking schedule tends to slow down as the year closes. I need the work, and you may need some story coaching.

That’s a win-win opportunity for us both.

The biggest year-end discount, and it’s a whopper, is offered for the…

Full Manuscript Read/Analysis Service

The goal is to see if your manuscript is ready for publication (either traditional of self-published… there is no difference in the criteria for either strategy). If it isn’t, I’ll tell you succinctly what works and what doesn’t, and do my best to suggest fixes and upgrades (that’s something that nobody on the planet can guarantee, by the way, just as nobody can guarantee publication; that said, I hope I’ve earned your confidence that I’m as capable of providing a blueprint for revision as anyone out there).

My current price for this service is $2250. The discounted price is… less. A LOT less.

Yeah, $2250 is a bit more than my prior fee, but the nature and scope of the feedback provided has evolved. More is better where feedback is concerned, and so I now deliver more of it. This analysis looks at – and gives an evaluation for – twelve different story elements and essences (the Six Core Competencies, and the Six Realms of Story Physics), all in context to an overall evaluation and recommendations for upgrades and fixes for your next draft.

My coaching document might be four pages, it might be 24 pages, but in either case you’ll have what you need to move forward with confidence.

The discount I’m offering, if you can pay now (in December), is 40 PERCENT off the regular fee… which translates to a discounted fee of $1350, a savings of $900. (The fee for this level of service reverts back to $2250 come January 1, 2016.)

Full payment ($1350) is required by the end of December 2015 to grab this discount. Contact me directly to arrange payment at the discount (see below).

But the good news is… you have until March 31, 2016, to actually submit your manuscript. Which gives you time to actually finish it, without pressure or rush, maybe even read my writing books and see what revisions you can come up with on your own.

A 40 percent discount on anything is a good deal. A 40 percent discount on something worth well over two grand… that’s a killer deal.

There is one other coaching/evaluation discount on the table.

The current fee for my Bundled Story Plan level of service (see below, or click HERE) is $395. Through December 31 of this year, however, you can lock in your involvement at a $50 savings (pay only $345, provided you can remit payment by December 31, 2015; once enrolled, you can opt to commence the service sequence at any time during 2016).

My fee structure has recently changed for my other Questionnaire-driven story element evaluations, including the way the Full Story Plan Evaluation works. It is now regularly-priced (at $395) as a bundled service (the fee includes each of the three levels) to incent opting-in for the whole coaching enchilada, completing the three levels in sequence (1. Concept/Premise Analysis, 2. Dramatic Arc Analysis, 3. Full Story Plan Analysis).

To learn more why this makes sense (there’s a really good reason that it does), and more details on how this works, click HERE.

To opt-in and grab these discounts…

… contact me directly – at storyfixer@gmail.com – to request an invoice and ask any questions you may have.

Other story coaching options at the regular fee remain available using the Paypal buttons in the left column, which also show the regular fee structure for these discounted programs. To grab the discounts, don’t use those Paypal buttons, write me to request an invoice (via Paypal; you do not need to be a Paypal member to use this venue for payment).

Unless you’re opting in to one of the one-off programs, in which case… please do.

*****

Click HERE to nominate your favorite writing post of the year, and thus, your favorite writing website of the year.

The post Year-End Story Coaching Discounts appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 30, 2015

Three Common Mistakes Made by Newer Writers

(Also this morning, I have a post on the mindset of revision – including an excerpt from my new book – over at The Kill Zone. Please return here, though, for a refreshing guest post from a passionate young writer.)

I receive frequent requests from writers who want to post here on Storyfix.com. That’s a nice compliment, but even so, as the gatekeeper, I find myself a bit on the picky side. But this one, while perhaps revisiting familiar ground, struck me as worthy of our attention. I value the fundamentals, and this is a nice refresher. And so I bring you…

A guest post by Leona Hinton

In today’s writing world, making your mark is rendered more possible with the availability of a vast array of available tools. Books and websites that help you craft a story that will attract readers. Editors and designers who will help you polish the final product. Conferences where you might just meet the perfect agent. Venues that will not only sell your masterpiece, but also help you format and digitize it, and then pay you a 70 percent royalty in the bargain.

These days you don’t need to be a millionaire to get your book published. Those days are long gone. But you do need to understand the steps involved, both creatively and technically, and the high standards you must reach to have a shot at success. And while much of the technology is new, one thing that hasn’t changed is a high level of craft, often years in the making.

Given the new nature and level of competition for readers, this is more true than ever.

Part of the journey involves avoiding the mistakes that cause other aspiring authors, especially newer ones, to stumble. Toward that end, I offer you three of the most common traps and pitfalls that await.

Mistake #1: Failure to decide who your readership will be before you write the book.

In other words, know your genre.

Your audience will respond not just to the plot and to empathy for your hero, but on an ability to understand your language, as well.

Perhaps this is most especially apropos when writing a children’s novel. You may indeed have a swashbuckling tale to tell, but you must deliver the theme, the plot and the characters with English that your young readership will not only understand, but will relate to. Got a Gen-X novel? You better not sound like your old high school English teacher. Unless you are writing adult literary fiction, each genre has its own tropes and expectations, the essence of which can and should be learned before diving in.

Mistake #2: F ailure to develop your book’s plot along a viable dramatic spine.

In any genre the author’s challenge is to engage with your readership, keeping them engrossed and hungry to move onto the next page or chapter. Exposition should be strategic, growing tension while ramping up to the climax , where tension and stakes are highest.

There are models and tools for that, as well. Structure – as Larry has told us many times – is like gravity. It just is. You may think you get to make it up for yourself, but as your story develops and feedback arrives (including your own sense of a need for another draft), the story will begin to align with the forces of structure, which are frighteningly similar in virtually any modern novel, in any genre.

Readers should be intrigued by the nature and source of conflict (internal or external) that drives the story along that structural spine. If you don’t understand – or better yet, haven’t discovered – the generic structural model for successful storytellers use, then avoid the mistake of taking it for granted. Or worse, ignoring it as formulaic.

Gravity isn’t a formula, either. It just is.

Mistake number 3: F ailure to fully develop the characters in your book before you stamp “final” on any draft.

Everyone who is part of your story should be both unique and relateable (those are not mutually exclusive terms). That means each character should be described so that the reader can literally visualize them, that they could sit down with a piece of paper and a set of colored pencils and draw your characters from the exact expression on their face to the type of clothes they wear.

And then, to make the character – at least the main characters in your story – multi-dimensional, with pasts and inner landscapes that come to bear on the actions and decisions they make within the present of the story itself.

Critics call these characters vividly drawn, and the analogy is apt: as authors, we are drawing our characters in multiple dimensions of depth and resolution, inside and out, past and present, with a future that logically links to all of it.

When you’re finally done…

… and when you’ve decided to self-publish…

… at some point in the near future you’ll face the need to advertise your book.

Wouldn’t it be great if once you could be an automatic success without having to venture into the dark and scary world of promoting and even advertising your novel? Unfortunately this is not the case.

Your Facebook profile is a good starting point. Many Facebook followers are on the lookout for anything dynamic and new, especially if they’re your “friend” and know you are an author. The theory is this: once they find your book, buy it and love it, the news will spread through the Facebook community. Other venues are available, as well, such as blogging, speaking and other means of getting you, and your story, out in front of readers.

Find your voice. Then strive for stories that create a framework that invites readers into new worlds, or new spins on familiar worlds. Give us something fresh and new, delivered with emotional resonance that results in a vicarious reading experience.

Do this, and begin to put in your 10,000 hours of apprenticeship in this craft, and you will never regret the time and investment of self required. That’s the beautiful thing about telling stories – we are our own readers, and from that high bar success becomes achievable.

Leona Hinton is a young editor and passionate educator from Chicago. She can’t imagine her life without creative writing and finds her inspiration in classic literature. Contact her on Linkedin.

The post Three Common Mistakes Made by Newer Writers appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 16, 2015

Coping With Trolls and the Irretrievably Lost… but Thankful for You

I’ve had a bit of a tough week. If I wasn’t the type who wants to please everyone, then the source of my temporary anxiety (a close cousin to temporary insanity, from which all sorts of bad things emerge), could be trivialized… but that’s me.

So here I sit, vacillating between two extremes.

Part of the tough week, of course, stems from the situation in Paris, where I was vacationing with my lovely wife (I wrote about that HERE) exactly one month ago. Having just been there makes the news clips more immediate and vivid, and the emotions – including rage – that surface without arms-length recourse (because I’m an arms-length recourse kind of guy) are frustrating. Unlike things we can excuse-away with a pithy “just part of life, dude!” rationalization, this stuff burns into the soul, while also showing us how people from all walks and corners come together as one mind and one heart.

From that alone, hope emerges.

Not so much with some readers of my book, it seems.

Closer to home, this week has been marred by three one-star reviews, one each for my three writing books.

Now, if you look closely, you’ll understand why this is just as embarrassing (to even mention it) as it is troublesome. Each review was preceded by five or six glowing 5-star reviews, which for the more mentally healthy author would make the one-star hatchet job nearly invisible.

But any one-star review gets your attention, and you’d think it would be from any valid criticism delivered. Not so. It’s the crazy, clueless, misunderstood and downright vitriolic intention of some of them that irritates and festers. People hide on the internet, saying things they’d never dare say to someone’s face… especially mine. If you’ve seen me, you get that.

Valid criticism is a gift. It makes us better. The clueless ramblings of the lost and angry reader… that’s just sad.

These aren’t my first encounters with the dreaded one-star, or the collision with someone who is bent on raining insults my way. When the first troll popped up in the Story Engineering review thread a few years ago – a guy named Bunker, who had never published a word, then or since – I made the mistake of engaging with him, which turned ugly fast (he said he wanted to come to my house and throw books at me… I gave him my address and begged him to show up, but of course he didn’t, because this type of reviewer is cowardly to the core; the invite is still open, by the way).

I wrote one of my writing guru buddies (James Scott Bell) about it, and his response was as brilliant, nourishing and as enduring as it was brief.

He said: “Pffft. A gnat.”

I have finally learned to not engage with gnats, because it never turns out well for either side.

Nonetheless, three more showed up online this week.

Mean spirited, as if I’d just insulted the entire history of their family tree.

One of the them, in particular, a review (if you can call it that) for my new writing book (“Story Fix: Transform Your Novel from Broken to Brilliant“) chock-full of inaccuracies, misperception and misplaced vitriol. And I choose to respond here simply to set the record straight, in addition to a much briefer response as a Comment below his review, which Amazon refused to take down (I’m always amazed at Amazon’s support of unfairness and clear slander in reviews, yet they take down responses that seek to clarify for readers who might be tempted to assign credibility; I’m also amazed at the number of people who click on finding such reviews helpful… that’s scary to me).

It takes a thick skin to publish anything these days. Trust me on this.

This review makes several inaccurate claims.

First… that I promise definitions of important writing terms, but don’t deliver them. Not true. I not only deliver them, I shine a light on them in context to the writing proposition itself.

Definitions of important story elements and essences appear – each under a thick black graphic header that could be missed only by someone who really never read the book (or doesn’t think they’ll get called out, or is thick-headed enough to not understand what they were encountering, which in this case were the very definitions this reviewer claims aren’t there) – on pages 46, 62, 93, 102, 109, 112, 115, 127, 128, 133 and 136.

Also, he claims the book is full of buzzwords. Interesting. This is like reading a book on, say, golf, and then claiming that words such as “chip shot” or “the rough” or “closest to the pin” are buzzwords. The only person who could possibly find a random buzzword in my book is someone completely new to the writing game. Which, in this case and supported by the review in whole, is clearly the case here.

Also, the reviewer says the book offers a “secret” to be revealed later (not true), and then claims I never deliver. This is where I refer you to the 18 five-star reviews (out of the 22 posted thus far) who disagree, and to the Foreword by Michael Hauge, who is one of the most famous writing teachers in the entire world, who used the word “brilliant” in describing it.

So why am I upset by one poor, sad guy – three, if you count the other two this week – who doesn’t agree? Especially when it’s abundantly clear that he shouldn’t even be reading a book on writing in the first place?

Interesting question. After well over 400 5-star reviews across my three writing books, I should focus on that, instead.

I should focus on the good stuff, like other authors commenting on my work, which also happened twice this week (read it HERE and HERE).

I think I’ve finally figured it out.

As a reader, writing a novel can look so easy. So the naive flock to a new writing book, unaware of what they’re walking into. Like someone strolling the streets of New York and wandering into a conference on brain surgery, hoping to find a free donut.

But what real writers know is this: writing a novel is complex. It’s challenging. It’s not something everyone can do well. The material in my books doesn’t shy away from this truth, and because I break the craft down into elements in way that nobody really has before, the new writer/reader may be intimidated, confused, and discouraged. Because it’s all so darn complicated.

They came for the kumbayah, instead they got theory and charts and layers of perception instead.

Imagine buying a textbook on, say, how to install your own furnace, when you’ve never tried anything like that before. And then, when you are overwhelmed, when you realize how little you know, you blame the author of that book.

That’s what’s going on, too often, where my writing books are concerned. This has been pointed out to me, many times, in fact, by writers who get it, who see right through these clueless one-star reviews (not all of which are clueless, some simply don’t like how I wrote the book, which is fair enough, especially since they are outnumbered across the board by about 10 to 1).

Writing a novel is every bit as complex as taking out a spleen. I know this because experienced doctors who seek to become writers have told me so. None of them, by the way, posting whiny one-star reviews because they can’t recognize what is true or principles that are more complex than beginning-middle-end… or encounter words they need to look up, but don’t.

Challenging commonly held beliefs – writing is full of them – is risky. It makes people uncomfortable. I’ve heard about this one, too… in this book I go right at one of those lofty ideals, that any idea is worthy, nobody can tell you that yours isn’t. But… it just might be, and that’s the problem that explains many rejections: agents, editors and readers don’t flock to – or throw money at – a bad idea, no matter how well written it is. I might be the first writer in this niche to suggest that maybe, just maybe, it’s a bad or even a weak idea that’s holding you back. And then, because I realize that offering this without a solution is the kind of thing that is bad business, I give you criteria and checklists to see if that’s the case in your story.

For some, that’s a solution. For others, even mentioning this is unthinkable. And so, they blame the messenger.

One of those angry reviewers said I sounded like a college professor. To her I say… thank you very much.

So, after setting the record straight on those missing definitions, I’m at peace with it all.

Trolls, the confused and the totally lost and clueless are on every corner, and Amazon invites them in without the slightest vetting or remedy. And by the way, I’m all ears for valid criticism, even when delivered with brass knuckles and a complete disregard for the author’s intentions (certainly mine), which in non-fiction is always to help the reader.

I’m constantly told I’m too wordy… so be it, I hear you. And I’ll hear the next guy who posts that, too, as if he’s breaking the news. And I’m working on that, but I’m a conversational, informal writer, if you want a dry textbook, go back to school.

If you’d like to comment on these reviews, or any others, you can do so in the Comment section available below every review posting on Amazon.com. And if you’ve actually read my new book, and are a serious student of writing (which mean’s you’ll know all the Big Words you’ll encounter), then you’re invited to review the book, as well.

As for me, I’ll never post a one-star review, for anything. Nothing, absolutely nothing, is gained by it, and having been in the bulls eye of a few, I know the damage it causes, not the least of which is painting an inaccurate picture for readers who don’t know enough to know a flawed review when they read one. Damage… not so much for the author, who will get over it, but for the poster him/herself, who can’t hide behind ignorance and the misguided chance to see their name online, which won’t happen any other way. Readers are, for the most part, smart, and they can smell a fraud with the first awkward sentence.

Amazon won’t take it down, either… you’re forever outed there.

*****

Next April I’m participating in what might just be the most comprehensive, amazing, life-changing writing conference… ever. Four days, only two instructors, and the deepest dive into craft you’ll ever engage with. It’s not cheap, but if you’re serious about this you’ll want to consider it. Click HERE to learn more… you’ll be seeing more of this on Storyfix.com as the date approaches.

The post Coping With Trolls and the Irretrievably Lost… but Thankful for You appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 12, 2015

The Finest Digital Tools that Turn You Into a Better Writer

The scariest thing about being a writer is that no matter how good you are, you can always become better. There is no limit to your capacity to produce extraordinary work that your readers would love. However, there is a certain appeal to the overwhelming challenge of becoming better: you can always explore new styles and themes, so your work can never be labeled as boring.

Do you know what else you can explore? Online tools that turn you into a better writer! Needless to say, you don’t want to get lost in the online world looking for the right tools to experiment with. You have work to do, so you would certainly appreciate a list of proven tools that will make you better in no time.

You are torturing yourself to remember a word you have in the back of your mind, but you just can’t spit it out? You need this reverse dictionary. Just describe the concept of the word you’re looking for, and you’ll get an entire list to choose from. The word you’re looking for is definitely in there.

2. NinjaEssays

You would have to invest a lot of money to hire a long-term editor you would work exclusively with. These editors usually work with published writers and charge amounts that newbies are unable to spend. That’s why you have NinjaEssays on your side! This is an online editing service that evaluates your projects and assigns a perfectly suitable editor for an affordable price. Plus, you can collaborate with professional writers, who can help you improve some aspects of your content!

3. Reedsy

You are already determined to become a professional writer? Then you need to become part of Reedsy – an online community that connects authors with great editors, designers, and marketers for their books. You can create an author profile for free, upload a portfolio, and start building connections. If you still haven’t discovered a publisher for your first draft, Reedsy will direct you on the right way.

Think about the greatest sin a writer can commit. Of course it’s plagiarism! You want to produce absolutely unique content with no signs of copying, paraphrasing, rewriting, and other dishonest strategies. PlagTracker checks your content and provides a detailed report about any plagiarism involved in it. If you accidentally got too inspired by an online resource and you forgot to provide proper citations, PlagTracker will help you fix the damage before it’s too late.

Some writers just love clichés. They are not aware of their habit phrases; they use them intuitively and bore the readers with unnecessary fillers. This online tool will help you locate the clichés and overused phrases in seconds. That’s a certain way of making your content less annoying.

6. Buffalo

Daily writing exercises are necessary for your progress. Buffalo enables you to write every day and publish your random thoughts online. It’s a supportive community that’s clean and extremely functional. All you need to do is join and start writing on any topics you have in mind.

You’ll see an almost blank page when you land at this website. Isn’t that all you need? You’ll access the options when you click on the lotus flower in the upper left angle of the page. You can insert pictures, change the font, download the document in different formats, or enter Focus Mode. You’ll also get character and word count, as well as an estimated reading time for your content. The distraction-free writing environment will make you a more focused writer.

These are the things that will support you on your mission towards becoming a better writer: commitment and the right tools. The list of online tools provided above will cover one of those aspects. Now, all you need to do is start using them and commit to a daily writing schedule.

*****

Robert Morris is a freelance editor from NYC. He loves traveling and yoga. Follow Robert on Google+

The post The Finest Digital Tools that Turn You Into a Better Writer appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 5, 2015

The Martian… Deconstructed

Two days ago I wrote about the phenomenon called The Martian, a 2009 self-published novel that against all odds found an agent and became a New York Times bestseller, and then was made into the current hit movie (and Oscar contender in several categories) by the same name, starring Matt Damon. The backstory of how this book happened and how it became the all-time dream-shot of any author in any genre, is covered HERE.

But you’ll want to come right back to this page (I’ll put a link there to make it easier), because, as promised, this post deconstructs the book to illustrate its structure. Which, in case you have no sense of what’s next, perfectly aligns with the principles and paradigms of classic story structure, with barely a single percentage point or two variance from the optimal locations of the major milestone moments that separate each of the requisite four story quartiles.

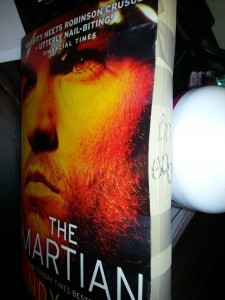

(If you’re noticing that this pic of the book looks, well, a little odd… there’s a reason for that, which will be revealed shortly.)

Coincidence? I think not.

If that second-to-last sentence reads like Greek to you, I recommend you bone up on the topic of story structure, using the Search function to the right of this page (keep clicking on “Older Posts” under the listings you see), or reading any of my three writing books.

Structure, in a story that works, isn’t something you get to make up. Rather – much like the wings of an airplane or the formula for a cancer curing medicine – it is something that is universal, proven and flexible only to a point (writers mess with this at their own peril), and it serves the writer (this being a massive understatement) who either plans for it or revises toward it, often unknowingly.

If you doubt this, don’t make any bets yet, because virtually every published commercial novel and mainstream movie proves this to be true. Even writers who don’t think of it this way or call it this, when they succeed, are following this structural paradigm. This includes writers who claim to be pantsers, and writers who mistakenly believe that “story trumps structure,” all of whom end up doing exactly this using a different vocabulary and process.

I have no idea whether author Andy Weir knew about or cared about story structure when he wrote The Martian, initially a series of blog posts which became a Kindle ebook and then a traditionally-published bestseller.

If he didn’t, you can bet that one of two things came to bear:

– he was either a savant genius who brought a keen story sensibility to the telling (because the very essence of a keen story sensibility by definition already aligns with the principles of story structure; this is the Stephen King approach, by the way… when he tells you to just sit down and write, to go with the flow, see what happens, he’s assuming you know what he knows… do you?);

– or, as Weir’s posts evolved via feedback or simply his own notions that changes needed to be made, the direction of his edits pushed the story into a closer alignment with the principles of story structure. Which almost always happens when the edits are valid.

When an editor says, for example, “nothing happens for too long, you need better pacing,” that is code for fixing your structure to include a stronger hook, a more powerful first quartile and a more effective and properly placed First Plot Point. All of which is structure in action.

The Basics of Story Structure

Using The Martian as a model, you’ll see that a well-told story breaks a story into four parts, of roughly equal quartile lengths, each of which has a unique narrative context, a specific role in the unfolding story. Separating those quartiles are three major story milestones (think of them as story twists, though each has a more specific mission than simply twisting thing), and then spicing up the Part 2 and Part 3 quartiles with a story beat known as the Pinch Point, which also has a specific role.

Here’s a picture of the paperback after I finished with it. I folded back the pages where the three major milestones were (circled), thus separating the book into four quartiles. And then, showing where the two Pinch Points are (within squares), in the exact middle of the Part 2 and Part 3 quartiles.

Notice how each quartile (the circled separations) is of roughly the same length. That’s classic story structure, demonstrated visually here for your learning pleasure (I added paperclips to make these divisions stand out, and circled them for the same reason). This is neither coincidence nor accident… this is how great stories work: they are told in four parts, separated by three major milestones, each with its own specific function and role.

Do this the next time you read a great novel, fold back the pages and see where they are, and you’ll see almost the exact same thing, provided you’ve accurately pegged those three story milestones..

This single fact can change – it will empower – your entire fiction writing experience. This is how it’s done.

Structure is driven by a core dramatic story – the main “through-line” plot, if you will – which also defines character arc.

If you can’t define your core dramatic story in one simple sentence, chances are you are spread either too thin or too thick. In The Martian, the core story is simple (it almost always is, even The Davinci Code‘s core story can be defined in one line): An astronaut is stranded on Mars, and he must learn to survive until a plan for his rescue is put into motion.

I’d say it’s not rocket science, but in this case it is. The inherent drama here is obvious, as it should be.

From this core story arises a core dramatic question: will Mark Watney be able to survive until the rescue plan can be put into motion? If that sounds just like the core story through-line, it is only in question form. Phrasing it as a question brings the story closer to a structural context. Because The Martian isn’t about simply describing how Watney survives; the dramatic question creates a context of why he must survive. The stakes are escalated, the pace fueled, the tension heightened. Huge difference. The dramatic question drives the story forward across the arc of the story, over four sequential parts (quartiles), toward a new and higher goal than what appears to be the state of things early on.

Instead of – and this becomes the mistake in many novels from writers who don’t get this or accept this – simply writing about a situation, even though it’s a fascinating one.

Which leads me to again offer this golden truth: a good story isn’t just about something… it’s about something happening.

Let the italics guide you on that one.

Today’s analysis of The Martian uses the mass market paperback to create a structural grid. The percentages, though, will be the same for the hardcover, the movie-tie-in paperback, and the movie itself. Structure is thought of in percentage of length, while illustrated using page numbers (for books) or minutes of running time (for films).

The total page length for the edition of The Martian used for this deconstruction is 369. Remember that when percentages are offered.

The First Quartile of The Martian

The optimal target length of a first quartile, concluding with the all-important First Plot Point, is 20 to 25 percent in. Which means the optimal location of the First Plot Plot (thus defining the length of the first quartile) of The Martian is from Page 74 to page 92. Any shorter and the author risks compromise to reader empathy and world building, any longer and the risk is boring the impatient reader with too much characterization or location details.

A good novel – a published book, especially within a genre, versus “literary fiction,” which still uses this to a great extent – almost without exception offers up a First Plot Point within that 20-25 percent-in window, not because someone said that’s the formula, but rather, that’s just (and it’s proven) how stories work best. Which means, if you are trying to create, or yielding to, being that exception in your story – if you follow your gut, and your gut doesn’t align with this – you are on tricky, possibly fatal ground, you are playing a low percentage shot in doing so.

Once you see how solid this model it, how prevalent it is out there, your storytelling gut will come around to it soon thereafter.

So how did The Martian do with these structural targets?

You’re gonna love this.

The First Plot Point of The Martian appears on page 82 (the 22nd percentile). Smack in the middle of that optimal location window.

And I assure you, this is neither random or coincidental.

The narrative context of a first quartile – in any story – is to setup and foreshadowing the core story. Not fully launch it… yet… but rather, to introduce the main character and antagonist (that one has more wiggle room, sometimes the antagonist/villain never really becomes vivid until later; author’s call on this one), give them a pre-core-story life and situation, create empathy and emotional resonance, set up the mechanics of the forthcoming First Plot Point (where the core story will fully launch, at least relative to the first quartile exposition), and place the whole thing in a vivid and vicarious story world environment.

When the opening seems to launch things in a big way, you’ll almost always discover that, however big, the real story isn’t fully in play at this point. Which is the case in The Martian.

The story opens with a killer hook: Mark Watney and the crew of the Hermes interplanetary transport are trying to conclude a scientific experiment on the surface of Mars when a nasty sand storm arrives unexpectedly. The landing/ascent vehicle is in peril, about to be blown over by the fierce winds (this is something the author concedes departs from real science, which other than in this opening is by-the-book everywhere else in the story; the atmosphere on Mars is only two percent as dense as it is on Earth, so a wind storm of any damaging magnitude is impossible, a 150 mph gust would feel like a mild breeze on Earth; Weir didn’t care, he needed something dramatic to kick things off… and this Martian tornado did the trick).

But the crew can’t find Watney. At what seems to be the last minute they hurry back to the MAV (Mars Ascent Vehicle), while the Captain cuts it even closer to remain outside in the urgent hope of finding him. What she doesn’t know is that Watney has been injured, he’s unconscious and the electronics in his spacesuit are offline. Based on evidence, they conclude Watney is dead. So, to save her crew and herself, the Captain barely makes it back to the ship and they blast off, heading safely back to the Hermes mother ship, leaving the “dead” Mark Watney behind, the fact of which devastates them.

Except, of course, Mark Watney isn’t dead.

And there you have the core story bones. The design of his spacesuit has saved him, auxiliary systems have kicked back in, and when he wakes up he’s totally alone… on Mars.

All that happens in the first six minutes of the film, the first 7 pages of the book. The hook concludes with Watney telling us all about it, after the fact, in his log, ending with this statement: “So yeah, I’m f**ked.”

And we’re hooked.

The first quartile goes on to literally build the story world, with rich detail on the harsh environment, the Hab in which he lives (which survived Weir’s contrived storm, but with some serious technical damage), and the challenge of not only surviving in the near term, but living long enough to actually have a shot at going home. Which at this point is hopeless.

So hopeless, in fact, that when the First Plot Point arrives, the story experiences a reboot. New hope. A plan manifesting in the face of the unthinkable. This is what First Plot Points do… they reboot the story, they actually ignite the core story from seeds planted in the opening quartile, or at least it kicks everything into a higher gear after a setup, a ramp up, in the preceding Part 1 initial quartile.

This Part 1 narrative also showed us what was happening back on Earth.

Mark Watney’s funeral, for example. But then a low-ranking technician monitoring visuals from Mars taken from orbiting satellites notices something odd. It seems like things have been moving around adjacent to the Hab that the crew had abandoned. After some debate there is only one conclusion: Mark Watney is alive, and healthy enough to, well, go outside and move things around… something we’ve seen from Watney’s POV in earlier scenes.

Is that the First Plot Point? No.

Because that moment doesn’t, in and of itself, launch a mission (figuratively, in the language of story structure, literally in this story). What that moment was is this: an inciting incident. You can have several inciting incidents within your first quartile, but don’t confuse them with a First Plot Point (unless it truly is one), which has a specific mission and location within the story flow.

About ten pages later, 0n Page 82, the earth-bound Hermes Mission Controller says this to a peer when asked about Watney’s odds of survival:

“No idea,” Venkat said. “But we’re going to do everything we can to bring him home alive.“

And that IS the First Plot Point.

Now we have a different, better story on our hands, with a higher degree of focus, direction, mission, urgency and risk than until this point. Everything has changed. Until now it was a documentary on how Watney stays alive. Now the story is about why he’s staying alive, with new hope and a mission, something new to react to… to get home.

The Second Quartile of The Martian

In this quartile we get further exposition about what Mark Watney does over the deadly quiet days, repairing and re-purposing technology, including growing enough potatoes to last him the hundreds of days he’ll need to remain alive long enough to… well, we aren’t sure yet. This is the fun and fascinating aspect of the story, the reader is rivited (akin to the puzzles in The Davinci Code and the operations of a submarine in The Hunt For Red October; smart authors take readers into places and details they’ll never encounter… the element of vicarious experience is wildly powerful in good storytelling).

Meanwhile plans are hatching and debated back on Earth, which is trying to land on a doable way to return to Mars to save Watney.

The target context, generically, of the Part 2 quartile is RESPONSE. Watney responds to the new parameters of the story, which shifted via the First Plot Point back on page 82, trying to stay alive as long as required and survive all the ways Mars conspires to kill him in the mean time. The space folks back on Earth are asked to do the impossible. Everyone is “working the problem,” and things don’t always go as planned.

That’s the essence everything that happens in the Part 2 quartile. Which includes…

The First Pinch Point

In any dramatic story, the reader needs to be reminded about the source of antagonism in the story, who and what the antagonist is, what they/it wants, and what lurks closeby, waiting to thwart the hero’s plans and/or swoop in to, well, do bad things. The reader, and the hero, can’t get too comfortable, fear and pressure need to resurface. This is called the Pinch Point, and there can be many of them… as long as at least two appear right in the middle of Parts 2 and 3, respectively.

The middle of Part 2 of The Martian is page 133.

Andy Weir delivers the first Pinch Point on page 143. Not far enough off to qualify as a deviation from the principle itself, which like all of these has wiggle room built in to them (meaning you still get to control the flow of your story, provided you don’t swerve into the wrong structural lane).

The Pinch Point is a scene (or a moment within a scene) written from the departing crew’s point of view, detailing their emotional experience from being forced to leave their teammate behind. It is gut wrenching, and completely what it was, as a Pinch Point, supposed to be: a reminder of the magnitude of the hero’s problem — he’s alone on Mars, unreachable, unsaveable, without hope.

The Midpoint of The Martian

If the First Plot Point is the most important moment in a story – and it is, from a structural point of view – then the Midpoint is not far behind. Once again the story changes as it marks the turn from Part 2 into Part 3, changing the context of the hero’s experience from RESPONSE mode into ATTACK mode. The hero, from an character arc perspective, evolves from a “wanderer” into a “warrior,” because now, leveraging new knowledge or change imparted at the Midpoint moment (you don’t need to be Stephan Hawking to figure out the optimal location of the Midpoint; in a 369 page novel, the target is page 185… do the math), the pace and dramatic tension of the story increase palpably as the proximity of confrontation, danger and salvation draws near.

The Midpoint is where the main character begins to get their hero on. It commences Part 3 of the novel… any novel.

The Midpoint of this story occurs when the folks on Earth complete hastily cobbled-together preparations to send a supply rocket to Mars with enough food and medicine and tools to allow Watney to survive until the arrival of the next manned mission, scheduled for over 400 days later.

This happens on page… get ready for it… 183. Two pages before the mathematical midpoint of page 185.

Coincidence again? Do you really have to ask?

The Third Quartile of The Martian

Which houses the second Pinch Point, within the new context of the hero at warrior/attacker of the main problem at hand.

There is another major plot twist thrown in there, too, illustrating the availability of all the twisting you want. A mission to deliver supplies to Watney crash shortly after take-off, taking everything and everybody back to square one. It works, but it’s not something that separates the quartiles… because it fits within the Part 3 quartile, where everyone is, contextually, attacking the problem.

Is this how you’re structuring your novel? Using these structural guides to optimize the dramatic effectiveness of your novel?

You should be… and in any genre. If your first draft is nowhere near these optimal structural milestones, now you have a guide for revision that will take you closer to them. Because trust me, if your novel isn’t aligning, if you don’t have these four distinct narrative parts (you can have more chapter and parts, but they should fit within these four organizational blocks), if the three major milestones (First Plot Point, Midpoint and Second Plot Point… along with those two Pinch Points in the middle of Parts 2 and 3) are nowhere near their optimal locations… trust me, your story is compromised. Maybe not broken – though that may be the case – but probably at risk.

If you know your core story, and if it’s strong at its conceptual core, and if you realize you aren’t there yet, you can fix it. That’s what structure is for… to save and empower your story.

If you doubt it, if you think The Martian is just a convenient aberration I’ve grabbed to prove this point, hear this clearly: I could grab virtually any bestselling, genre-driven novel, or even any published novel at all (traditionally, because unlike self-published books, traditional publishers look for and vet these structural principles), I guarantee you it would be a model structural citizen, as well. Because it works… and structure is a huge part of why.

The Second Pinch Point in The Martian

Of course, just because your hero is now a Warrior doesn’t mean things will fall easily into to place. That’s why we have that second Pinch Point, optimally located squarely in the middle of the Part 3 quartile to once again remind us of what could go wrong, and how the hero has more risk and more work to do before the core story problem/opportunity will be resolved.

In The Martian, the second Pinch Point is a whopper. Basically, Watney blows everything that was suppose to take him home to smithereens. More importantly, the communications equipment that was allowing him to trade information with his rescuers on Earth… it’s destroyed. Beyond repair. The entire rescue operation is dead… both sides, on Mars and on Earth, have to start over.

This happens on 228, which is the 62nd percentile of the story’s length. The optimal placement? The 62/63rd percentile.

Story structure is amazing that way.

Still in Part 3, the team continues to “work the problem,” which translates to attack the problem, which is the generic mission context of any Part 3 narrative. A new plan emerges, but it’s unthinkable risky: Mark has to drive – literally – across harsh Mars terrain for over 3000 kilometers to rendesvous with a previously depositing Mars Ascent Vehicle, which has been deposited there earlier for use by the aforementioned mission, still some 400 days away.

The Second Plot Point of The Martian

In a later turn, the crew of the Hermes defies orders and steps into a plan to return to Mars (at great risk… the drama explodes off the pages and off the screen) to rescue their abandoned teammate, Mark Watney. The rendesvous will be in low orbit over Mars, with a ridiculously low margin for error. They will have one shot.’

Provided Mark can reach the MAV in time, strip it of several tons of burdensome equipment, survive take off and somehow manage to grab the hand of a Hermes crew member passing by him at 12 meters per second… with no do-over possible.

Yeah, that’s some serious drama. Why does it work? Why are we rooting for this, with every fiber of our being? Because Watney has our heart. We love him. We respect him, he’s MacGiver in space, and he deserves to come home.

The optimal target location for the Second Plot Point in a 369 page book is page 277.

The location of the Second Plot Point in The Martian – when Mark leaves his base HAB for the final time, loaded down with jury-rigged equipment, in quest of the Schiaparelli Crater where the MAV awaits, over 3000 kilometers away – is on page 284.

I won’t say it. About this being a coincidence, I mean. A few pages on either side of an optimal structural location mean nothing, provided the mission of the milestone is effective, and the context of the ensuing quartile shifts into place.

The Fourth Quartile of The Martian

In essence, especially in thrillers and in many mysteries, romances, YA and other genres, the fourth quartile is consumed by a final chase scene, or push (the case here) toward the moment of truth, or a confrontation of some kind.

The first pages of the quartile show us the machinations of the forthcoming climactic scene, and the second half immserses us in it, sometimes with scenes that ramp u to it, followed by scenes (epilogue in nature) that show us the aftermath. (For the record, the movies shows us aftermath that the book doesn’t, seizing on the opportunity to show us the post-mission Watney in good health – yes, he survives, did you ever doubt this – and the chance to wax thematic on the strength of the human spirit.

I hope you’ve found this deconstruction illuminating, helpful, and motivating. If nothing else, I hope it makes you want to read the book or see the film, perhaps both, perhaps again, to see how these quartile contexts and milestones are what drive the whole thing, dramatically and emotionally, toward a finish line with a huge payoff.

This post took me over ten hours to research and assemble. I hope you enjoyed this. And I hope it licenses at least a glance at the little promo copy below. Thanks for reading.

*****

My new writing book, “Story Fix: Transform Your Novel from Broken to Brilliant,” is on the surface a book about revision, but in fact is a book about how to connect your narrative to these structural principles in a way that results in emotional resonance for your reader within a powerful and rewarding vicarious experience. The initial reviews are amazing, I hope you’ll check them out and give the book a shot. This is the book that may get you published after all.

My #1 bestselling first writing book, “Story Engineering: Mastering the Six Core Competencies of Successful Writing,” introduces these structural principles in exquisite detail, and shows how they empower five other essential realms of writing skills and essences. This book will move you from beginner to skilled professional once you wrap your head around it.

My award-winning second writing book, “Story Physics: Harnessing the Underlying Forces of Storytelling,” shows you the connection between structure, character and narrative strategy as it relates to evoking reader response and emotion. In other words, why the principles work as well as they do, which may change everything about how you choose and develop your stories.

All three books are published by Writers Digest Books.

The post The Martian… Deconstructed appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 3, 2015

Story Structure and the Self-Published Home Run

Andy Weir is a self-confessed geek.

He is also the author of the bestseller, The Martian, the film adaptation of which is in theaters right now.

He was (the tense there is important) a computer programmer by day, a science fiction fan and aspiring author by night.

Weir is a guy who sweats the details in all things, and those details – technical veracity that doesn’t depend on concoction – often escaped him in the stories he read for pleasure. He’d submitted a few of his own manuscripts to agents and publishers, but nothing happened, perhaps because they were loaded with those details.

Sometimes that becomes the juicy irony behind a massive success story.

Kathryn Stockett, for example, submitted a manuscript entitled The Help to 46 so-called elite agents, and not one of them signed her. Remember that one when your next rejection slip arrives. William Goldman was spot-on right when he said of Hollywood and the publishing machine, “Nobody knows anything.”

If you like stories like this about writers who don’t give up, about pathways to success that are anything but traditional, keep reading.

This one is for you.

Andy Weir had an idea. A concept, really (as defined in my new book), because while compelling, it had no hero and no dramatic arc… yet (which exactly fits the mold of the definition of concept). It was just something he wanted to explore. And so he began writing what amounted to short chapters on his website, launching a story about an astronaut who, through no fault of his own, finds himself stranded in Cleveland without a wallet.

Okay, that’s not true. Just seeing if you’re tracking with me here.

His protagonist found himself stranded on Mars.

The story became a sort of diary about all the things he had to confront to survive, most of which could easily kill him, and how he MacGivered his means of survival, cobbling together all kinds of solutions and tools with absolutely accurate science. No ending yet, just the unfolding tale of Mark Watney and his time on Mars.

Soon those blog posts had a following. Some readers were fellow science geeks who gleefully corrected anything (as science folk usually do) that wasn’t realistic. After a while, when a killer ending manifested (this has to happen before any manuscript will work), one of those readers suggested Weir post the chapters online for all to read as a singular collated manuscript. Weir selected Amazon Kindle for this, posting it for free.

It didn’t take long for takers to show up in the tens of thousands.

The Martian became the #1 free Kindle book, inspiring another reader to send Weir an email that said something like this (I’m assuming and paraphrasing here): “Dude, you need to sell this. You’ll get even more takers.”

Because across the vast sea of readers out there, most still assume that a story selling for real money is better than something available for free.

So Weir published The Martian for 99 cents.

(Sorry, it’s nine bucks as of today.)

And as predicted, sales instantly explored, reaching the coveted #1 Kindle book throne very quickly.

Andy Weir was a happy science guy, this outcome far exceeded his expectations.

But fate was just getting started turning his story into an unthinkable dream shot.

An agent found him and offered to take The Martian into the dark world of traditional publishing. Weir said yes, his expectations nowhere near what was about to happen.

Very soon thereafter the agent called with the news: he had found a publisher who would pay a mid six-figure advance for hardcover rights.

And then, the agent called four day later – sit back and allow that one to sink in – to announce that the movie rights for the book had sold, also for significant cash.

That was a good week for Andy Weir.

But then, the odds descended. Only a fraction of these movie deals ever reach the screen. So Weir wasn’t counting his chickens… yet.

More good news. Ridley Scott, perhaps the biggest name in high concept movies, wanted to direct. And Matt Damon would sign on to play Mark Watney, the stranded astronaut.

Shortly thereafter the novel became a New York Times bestseller.

Imagine, if you can, this happening to you.

It’s the most delicious self-publishing success story since Twilight, which had a similar path. Other self-published novels have found significant success as well, but don’t forget that the path to the bestseller list and the silver screen remains a steep and arduous one for self-published authors, the odds remain orders of magnitude higher for traditionally published projects.

But then, you have to land an agent. And if your self-published project finds one for you, that’s the best outcome of all.

Why does The Martian work so well?

Have you read the book or seen the film, which is quite close to the dramatic and details of the novel?

Two things jump out. First… the concept is killer. Concepts alone can make or break you, and this one is an example of the former. Before you add the hero, the situational center-piece of the concept is irresistible. It drips with dramatic potential, and the closer you look at it, a rich stage for character and theme crystallizes before your mind’s eye.

That alone makes this novel – not to mention the story behind it – an ideal model for deconstruction.

But it is the structure of the novel (and of the film, which matches identically) that elevates The Martian as an even better learning model. Because its structure is perfect. Quartile by quartile, story milestone by story milestone, scene by scene, the architecture of the novel is a poster child for classic four-part structure (3-Act structure if you’re still stuck in that less precise model, which is the same basic sequence).

In my next post I’ll walk you through The Martian from a structural perspective, defining those quartiles and parts and their specific locations within the novel.

But I’ll tell you this now… those major story milestone occur within only a few pages of their optimal target. And that isn’t remotely an accident. If you are skeptic, allow this to convince. If you are already a student of structure, all this to pump fresh adrenaline and hope into your writing chops.

The question then becomes, how did Weir pull that off? Is he a student of some form of structure, or is he a pantser who somehow found the thread that would make his story work?

I certainly don’t know, but from what I’ve read, Weir is a candidate for structural thinking (most programmers are). And even if he’s a panster, the likely backstory is that as he revised the story based on feedback and his gut story sensibility (that’s the story of every successfully pantsed novel, drafts evolve, and the end-zone of the evolution almost always aligns with the principles of structure, whether they want to acknowledge it or not), it moved closer and closer to the paradigm that awaits all of us, even in a first draft if you understand it well enough.

Until then, head to the theater or grab the paperback (which I read in one sitting while on a flight from Paris to Salt Lake two weeks ago, an 11 hour sequestering that my wife and I are just now recovering from).

Thank goodness, and Andy Weir, I had that paperback with me. And thank goodness someone like Ridley Scott and Matt Damon made it happen for him in Hollywood.

Now you can benefit from the learning the story makes available.

*****

It’s November Mustache Month… a Challenge for Men’s Health

I’m posting this for my son, who is 25 and lives in Austin, Texas. He’s growing a mustache for his fund-raising efforts on behalf of the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the Prevention Institute, the Livestrong Foundation, Ichom, and several corporate sponsors, for men everywhere who would benefit from preventative and care programs that will save and enrich their lives.

I’m proud of my son for doing this.

I hope you can toss a few bucks toward this cause, using this THIS LINK to donate.