Larry Brooks's Blog, page 29

June 11, 2013

The Secret Weapon of Story Physics: Narrative Strategy

A story is always the sum of – the outcome of – a huge pile of author decisions: where to start, how long, how soon, how to end it, where to end it, what not to end, how much, how little, when to show this, when to say that…

… all of it, hopefully, arriving in context to some basis for the decision itself… for an informed notion of why.

The basis is often simply your gut instinct. Good if you’ve got one. Even better when driven by a grasp of storytelling principles and physics and a few tries under your creative belt.

Too often, though, as you stare down the barrel of a new story, the basis for these decisions is caught wandering somewhere between the first thing that comes to mind, comfort level and casual randomness.

No matter how you decide, or what you decide, there is always one other choice – a different kind of choice — that looms even more urgent than what-goes-where.

The most visible decision you will make is your narrative strategy.

Because you really can’t write a decent word, not a single paragraph with ambitions of being in its final form, until you decide upon narrative strategy.

What is narrative strategy?

It’s how you will narrate your story. It is the voice of your story.

Pretty much everything else you need to decide upon defines the WHAT of your story. The expositional content of it.

Narrative strategy, along with structure, leads you toward the HOW of it.

Structure is the sequence of your story’s unfolding.

Narrative strategy is the actual mode in which you tell it.

And, like a singer’s tone or a painter’s technique or a State of the Union address’s political context, it is critical to making it all work.

If you think of your story as a journey from point A to B, structure is the route taken. The order in which information is delivered to the reader.

Narrative strategy is the vehicle in which the reader will ride. The contextual means of the delivery itself.

Who is telling your story? The hero? The hero’s neighbor (think “The Great Gatsby”)? A few folks? God, or some omniscient, all-seeing voice?

And then… how are they/he/she framing it all?

Your story’s ultimate fate may rest on this one single decision more than any other.

The Default Narrative Strategy

The most common voice of a story, the one we were taught first back in the day, is third person omniscient narrative. The “god-narrator” perspective.

Bob walked to the ledge and looked down, seeing nothing that would change his life, as he’d feared.

It allows you to look anywhere and notice anything, including what a character is thinking. It even allows you, when handled correctly, to know what others are thinking in the exact same moment.

Because the god-narrative knows all, sees all, and may or may not tell all.

From there you can, within this constraint, narrowed the point of view to create intimacy, nuance and detail:

Bob walked to the ledge, conscious of a sea of eyes following him, his stomach churning at what he feared might be a moment that would change his life forever.

About the only hazard on this narrower road is point of view… like First Person narration, “tight” third person demands that you not mix multiple points of view within a given scene.

Third person, in all its common forms, is the one your high school creative writing teacher told you was the proper way to tell a story. In some cases, the only way.

That particular piece of advice is in the running for the worst, if not the most out-dated, writing advice dispensed in the last one hundred years. Tell that one to Holden Caulfield and Mike Hammer and a girl named Katniss, among a few hundred other literary iconic heroes. If you’ve read a bestseller lately, you’ll know that conventional wisdom has long since been debunked.

First Person Narration

Perhaps as much as half of the novels being published today are in First Person.

I moved slowly to the ledge, locking a death grip on the railing before allowing myself to look down, wondering if this would be the moment my life changes forever.

In a given moment the reader is privy to what the character is seeing, feeling, perceiving and feeling, in a way that is less constrained by logic and colored by world view and backstory. It is the quickest and clearest route into the mind of a character, often including humor, irony and some hidden darkness that only the reader sees.

In my view, First Person becomes the default choice for stories in which an interpretation of the unfolding exposition is the focus of the story. First person marries nicely with another of the Six Realms of Story Physics – the delivery of a vicarious experience.

And yet, some writers remain wary. Could be comfort level, could be lack of confidence. My advice: try it out. You may immediately realize you’ve found your default voice. That you’ve arrived home.

That’s precisely what happened to me. It was at that moment of decision that my writing career took a turn.

The First-Third Combo Meal

Point of view is a force of nature, it demands a singular scene focus without compromise. And yet, the choice of First Person narrative as a strategy comes with a price – you cannot show what takes place (either in the past or present) from beyond the limits of the narrator’s scope of awareness.

And yet, many stories depend on such behind-the-curtain building of suspense and the means toward the confluence of story forces.

What to do?

Make your high school writing teacher roll over in her grave by combining the two within a story. Actually writing scenes that come from one or the other voice – first or third – that show the first person narrators perspective, and the elsewhere perspective, as required… in the same story.

The only rule: never do this within a single scene. Either create a new chapter, or skip lines to define a scene shift, whenever you switch from first to third, or third to first.

If this is your approach, make sure to give roughly equal time to both voices, and use the device strategically to build suspense and manage pace. You’ll quickly find you have a lot to work with in those regards.

I first saw this done in Nelson Demille’s “The Lion’s Game” and then it’s sequel, “The Lion,” and it blew me away. It impressed me to the extent that I did it in my own novel, “Bait and Switch,” and in every novel I’ve written since (my new novel, “Deadly Faux, “ out in October from Turner Publishing, employs this narrative strategy.

It’s out there everywhere. Another arrow in the quiver of narrative strategy.

The goal is to find your best voice, rather than settle for default choice.

The Enhancement Choices

First versus Third Person isn’t the only choice on the writing table. The writer must also elect either past tense or, in an emerging trend, present tense.

Third Person Present: He walks to the ledge and looks down, seeing nothing that will change his life, as he fears.

First Person Present: I move slowly to the ledge, locking a death grip on the railing before allowing myself to look down, wondering if this will be a moment my life changes forever.

Suzanne Collins used First Person present in “The Hunger Games” series, with great effect. These stories read much like a screenplay (that’s no accident, all screenplays are written in present tense), adding to the sense of vicarious immersion and experience.

But notice how, in those books – unlike the films – you see nothing that Katniss cannot see. It’s no accident the movie did it differently, creating added tension by allowing the viewer to understand the emerging danger before Katniss herself does.

In Kathryn Stockett’s mega-hit “The Help,” she went even further out on the strategic limb with this choice: she has three different First Person (past) narrators. Each occupying the role of protagonist/hero, and each integrating with the others. Many scenes have two or more of the characters involved, but always within a consistent narrative point of view for the scene itself.

These choices comprise a matrix of options for your consideration. First or third? Past or present? Mixed person, or singular? Multiple narrators with a consistent voice, or multiple narrators from both first and third?

You get to choose. The question is… how?

The Challenge of Choice

This is a challenging proposition. I’ve read many stories in my coaching and evaluation work that would work better in First Person, which is a tough piece of feedback when the writer has already written 400 pages in Third Person.

Much better to get this right before you begin the drafting process.

The key to the optimal decision is your understanding of the potential and limitations of each strategy, merged with your understanding of the dynamics of the story itself.

With a touch of comfort level thrown in.

How much exposition takes place outside of the scope of your hero’s awareness?

Whose story is it? How many points of view are there?

How personal is the story? How important is getting into the hero’s head and experiencing that chaos, emotion, elation, and the confusion of not knowing what things mean?

Does your story rely on wit? Humor is much easier when it comes from the head, and the lips, of the narrator.

Where is the dramatic tension coming from? How much does the hero know, or need to know, about that information?

I don’t think there’s a hierarchy of criteria that lead you to this particular Narrative Strategy choice. I believe you need to trust your gut. Which means you need to develop your gut instinct, whatever that takes. And, perhaps do a little research to see how other novels with similar premises and qualities to yours (yes, they’re out there) have been handled.

At some point you’ll know. Hopefully sooner rather than 400 pages later. You’ll know because, from an informed context, it’ll just feel right.

That feeling with either lean toward random and uniformed, or take-it-to-the-bank supported by basis for your decisions.

And thus are made bestsellers and rejected manuscripts. We live and die by our feel, our instincts, and the database of storytelling knowledge that informs them.

The more you know about your story, and the earlier you know it, the more optimal your choices will be.

******

Narrative Strategy is one of six key realms of Story Physics… as defined in my new book, “Story Physics: Harnessing the Underlying Forces of Storytelling.” Available now, online and in your local bookstore (after June 18).

*****

Have you ever wanted to kill your writing teacher? Hmmm….

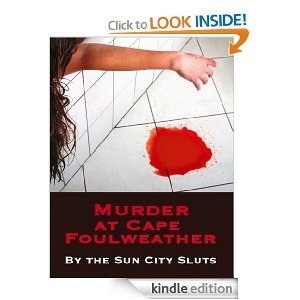

A few writer friends have just published a fun new mystery called, “Murder at Cape Foulweather (A Sun Slut Mystery)“… if that doesn’t foreshadow the tone, nothing will. It’ s about a weekend workshop with a writing teacher from… wait, no, it couldn’t be… they swear it isn’t… anyhow, it’s a story full of secrets and sex and, I assume, a dead writing teacher. Sounds like fun. These women are really good, and really funny, so it’s worth a look. Already have my copy, and I’m hooked. Hoping you’ll check it out.

The Secret Weapon of Story Physics: Narrative Strategy is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

June 7, 2013

It’s My Blog and I’ll Cry If I Want To

NOTE: this is the rare Storyfix post that isn’t directly about telling stories. This is about dreams and memories and goals and regret and what we do with it all, which you can easily spin into a perspective on the writing life.

Or just life itself.

I do, on both counts.

A long, long time ago, on or about this date, I arrived at high school baseball practice to find the father of a teammate waiting for me. With some big news: he’d just heard on the radio that I had just been drafted by the Washington Senators. Twentieth round.

My life suddenly changed. The only thing, on a career level, that I can compare it to is the day I got the call informing me that I had sold my first novel. That, too, was a while ago.

Cut to yesterday, June 6, 2013, when professional baseball held its annual free agent draft. Some of the drafted come right out of high school like I did, and some of those pass on what professional baseball is offering and opt for college baseball instead. The others are college players whose only remaining option is pro ball, with an obligatory apprenticeship in the minor leagues.

Either way — whether it’s a baseball or a keyboard — the journey is only beginning, the road ahead is long and arduous, and perhaps blissful, as well. If you do it right.

Thing is, for most guys it doesn’t last.

You can’t totally control the outcome. You can only control the time and effort, the heart, that you put into it.

Every year on this date, or whenever the draft happens, I harken back to that day when my name was on that list. I signed with Senators, who two years later become the Texas Rangers, and for five years kicked around the low minor leagues trying to find home plate with a decent fastball and a slider that had the temperament of a stray cat.

And then it ended. A black day in the journal of my life. It was back to reality, a much different long and arduous road for me.

It was then that I discovered writing. And another dream was born. One I’m still working on.

To not have a dream, to pursue a goal, no matter how old we are, is to be dying.

That’s why I love writing. Even on those days when I don’t. You only have to be able to think to play this game at the highest levels, and getting there is a door open to all.

Draft day is an emotional one for me. Not so much because of regret, which is certainly in the mix (regret not so much at not making The Show, but at what I could and should have done differently, on several levels), but because of the passage of time itself being rammed right down my wrinkled old throat, holding a mirror up to all facets of my life. Don’t get me wrong, I do celebrate getting the shot, and the memories are as fresh as if it were just last year. I’ve had decades of dealing with dismissal (“oh, you were just in the minors then…”), of misunderstanding (minor league baseball, at its lowest level, overall is equal to and usually superior to the highest level of Division 1 college baseball) and generally nobody really giving a shit about what remains, for me, the most precious of memories.

It wasn’t a squandered opportunity. It was a privilege and a stepping stone. A clinic in life.

The upside, the memories and the lessons remain mine alone, conversationally appealing to absolutely nobody in my life except my wife. I married well, my wife loves baseball, one of a massive handful of reasons I remain a very lucky man.

And so I juggle regret with an acknowledgement of those lessons learned, applied to a new dream that nobody, despite the collective forces of an avocation built upon rejection, can kill.

It’s interesting to note how little coaching and mentoring I received in professional baseball. I threw a fastball as hard as the guys drafted in the first round yesterday (mid-90′s), and while I wasn’t the best athlete on any of those teams (that particular bar was very high), my arm was there. I wonder what would have happened had someone taken the time, applied the knowledge and the patience, to school me in the little things, the strategic things, the stuff that almost nobody who hasn’t worn a uniform understands about how and why a pitcher becomes successful in competing with professional-level hitters.

By and large, as a pitcher, I was like a reader of novels who has absolutely no clue about what the writer has to do to make a story work. Throwing hard… that’s only the ante-in.

The most talented guy I played with, and my best friend in the game, was a first round pitcher named Jim Owen, who didn’t make it either. But his story was different… he walked away from baseball after a few years riding buses, the only player in my entire experience that actually did that, though many claim to have quit (they’re lying, they got released like everyone else).

He knew who he was and what he wanted, and when that clarified for him he set out on a different path to get it. And did.

And thus, my point today emerges, for your consideration.

Raw talent… big deal. You can write great sentences and emails… big deal. That just gets you a tryout. Gets you drafted. There is nothing special about unrefined, unschooled talent. In fact, talent isn’t even at the top of the list of what it takes to make it, in baseball or in writing.

Once you’re playing in that league, other variables enter the proposition to determine your fate. Among them is your head, your approach to the game, your tolerance for failure and frustration, and the willingness to do the hard work of moving forward in an ever-ascending assault on the learning curve.

The guts to persevere. To find some measure of bliss while sitting alone in a room with your story, no matter what happens to it.

That’s what my baseball experience taught me about life. About writing.

I sit alone in a room with both… my stories, and the ghosts of my baseball past. Both, painful as they are, embrace me with that bliss.

It’s the little things. The craft. The nuance. The Big Picture melding into the minutiae, tempered over years of building sweat equity and learning from the losses.

In baseball and in writing.

Thank God for both.

****

Another personal note: some scumbag in Nigeria has hacked into my email and is using my contact list to send out… God knows what. Many of you are on that list, so if you received one of those emails I apologize… wasn’t me. I’ve changed my security settings, it appears to have worked.

What I wouldn’t give for five minutes in a room alone with that asshole, sans machete.

It’s My Blog and I’ll Cry If I Want To is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

June 5, 2013

So what are “Story Physics,” anyhow?

Just in case you think writing books, or any other book for that matter, are a grand conspiracy between author and editor, with the occasional agent chiming in, consider this: when I was writing “Story Engineering” (my first writing book), I used the term “story physics” several times to describe how and why stories work.

“You know,” I explained to my confused editor, who majored in English Lit and not science, “like gravity. The forces around us that control everything. Stuff we can’t change or avoid, but are nonetheless available to use to our advantage.”

He then said, “explain to me how writers use gravity.”

He made me take it out.

Now, as my new writing book comes out (not coincidentally entitled “Story Physics“), I may have some explaining to do. Not so much to that editor (who a., was great, by the way, and b., isn’t my editor on this new book… she’s great, too), but to readers who find the term… something other than and less than writerly.

You know story physics by other names. Dramatic tension. Pace. The mystery and intrigue and thrills and emotional resonance of reading a great novel or seeing a powerful film.

Of course they’re there. It’s the point of writing a story, right?

Perhaps.

But here’s the hypothesis upon which I’ve based the new book, along with the delivery of a greatly expanded roster and definition of the unavoidable forces that will make your story work, or not: they can be harnessed.

And for that to happen, you need to understand them thoroughly, not so much as the consequences of the creative choices you make, but as the pre-determinants of the effectiveness of those choices. You need to know how and where and when to plug them into the stories you write.

Left on their own without your oversight, without your very conscious touch, story physics become a consequence of what you’ve assembled on the page. They are the sum of your story premise and the skill with which you’ve rendered it.

Which is precisely why some stories work better than others. Story physics, like gravity, are always in play, both at the story development stage and at the story impact/effectiveness stage. There’s no getting around it on either side of that.

You ignore story physics — leaving them to the aforementioned sum of the parts — at your peril. Or, you can manage them. Optimize them.

Can you truly say that in your last story, every single decision you made along the way was the best possible dramatic and expository choice available to you in that moment of creation?

If you can, then either your name is David Baldacci or you are kidding yourself. Perhaps without even realizing it.

The Connection Between Core Competencies and Story Physics

My first writing book introduced six core competencies that every writer needs to address in the construction and execution of a story. Like the story physics that energize them, to not address them, or even acknowledge them, is to leave them to chance… because they are present regardless of the writer’s awareness.

You can either fall out of an airplane without a parachute, hoping you land in a pile of feathers next to a barn… or you can use a parachute. Both are completely governed by the physics of the moment. It is the same with the stories we write. We get to choose.

The six core competencies are tools. And like any tool, they are a matter of degree when applied.

The force — the power, the compelling energy — driving each of those six core competencies is one or more of the six realms of story physics. This is a different six-some altogether, as different to a story as strength and eye-hand coordination are to an athlete. One empowers — in this case, literally fuels — the other.

You swing the hammer hard or you swing it softly. You select low or high. You press down or you use a light touch. Each choice defines the power and effectiveness of the tool, which must be matched to the degree of power and touch appropriate to the task.

There is the tool… and there is how the tool is applied.

Again, just like in our stories.

Story physics are the natural literary forces behind the creative choices you make (the application of the tools, as represented by those six core competencies) during story development and execution. What goes where, and why.

These six realms of story physics are always in play, for better or worse: compelling premise… dramatic tension… pace… hero empathy (emotional resonance)… vicarious experience… and narrative strategy.

Optimize them and the story works. Under-cook any of them and the story suffers for it. It’s that simple.

“Story Physics” (the book) closely examines each, and juxtaposes them against the six core competencies (tools) that rely on them to work. With a deep dive into two bestselling examples that harness all twelves of these forces and tools with exquisite effectiveness.

Whether this sounds like entry level stuff to you, or the magic that awaits behind the curtain of the grand illusion of storytelling, they remain the supreme qualitative factors and forces in your stories… always.

I’ll be writing more about each realm of story physics over the summer, and connecting them to the specific core competencies they empower.

Until then, consider this:

Which is the more powerful and compelling premise: a love story between two kids growing up on farm during the depression… or a love story between a black depression-era farmhand and the white daughter of the land baron who killed the boy’s mother after raping her?

The difference is story physics, pure and simple. Not just at the conceptual/premise level, but on every page in the manuscript.

Prepare to go to the next level.

****

Story Physics is available now on Amazon.com, and will be released in Kindle, Nook and other digital formats in mid-June; it will be available in bookstores (remember bookstores?) then, as well.

****

Read an recent interview on this topic at Writing That Changes You.

So what are “Story Physics,” anyhow? is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 31, 2013

My Pseudo-2Q Newsletter Update With a Few Gratuitous But Nonetheless Valuable Tips

“Story Physics” has shipped.

If you’ve pre-ordered my new writing book, “Story Physics,” chances are you have it in hand. The official pub date is still three weeks out, so the Kindle version is just around the corner.

First reader feedback: “I read the Introduction and experienced a shift in attitude toward writing, a clarification of my relationship to my own work, so please, teeter no more. If the Introduction can do that … I find myself torn between wanting to read the rest of the book in a single gulp, and a more leisurely pace, to allow further shifts to occur and be integrated. Scary good, Larry.”

Good to get that first one under the belt.

Conference/Workshop Update

Writers Digest has invited me to teach as session as their annual Writers Digest West Writing Conference, September 27-29 in Los Angeles. Will forward website info on that when available.

I’m also teaching three sessions at the Willamette Writers Conference, August 1-4 in Portland, OR. Click HERE for more on that one, it’s a massive conference with killer breakouts and an entire wing full of agents taking pitches. Great for screenwriters, too, with dedicated sessions and Hollywood pitches. Manuscript reviews, too.

Art Holcomb Update

Our favorite Storyfix guest blogger, Art Holcomb, is teaching a session at The Greater Los Angeles Writers Conference (“greater” because Art is there, IMO), June 14-16. Click HERE for more on that… and HERE for more on Art. Use the Search function to the right to find his killer posts here on Storyfix.

Best Concept Definition Ever

The recent posts on concept — what it is, and what it isn’t… what it isn’t being your story’s premise — have stirred up some interesting and valuable feedback. The definition is imprecise, and often leans into premise itself.

A Concept is simply something conceptual at the heart of your premise. A compelling notion or proposition. Something that stands alone as a source of energy that fuels the story.

A premise is the dramatic story, with a protagonist, that evolves from the concept, that seizes that energy, that builds a story upon that conceptual stage.

If your “concept” sounds more like a book jacket synopsis, then it’s probably a premise. If it comes off as a killer idea or notion that could inspire any number of stories, because it’s that cool or scary or original or heavy… that’s a concept.

Trust me, I’m as tired of writing about this as you may be of reading about it. But, based on what I see in the story evals I do… more focus and depth on this issue is necessary. Four out of five writers get this wrong, and in doing so miss a great opportunity.

Story Coaching Update

Effective June 15, I’ll be raising the price on my $100-level story coaching service. It’ll be $150 after that, with a revised Questionnaire that drills deeper into the concept vs. premise issue… AND, all submissions will be a one-week turnaround (an upcharge to $180 will get you a 48-hour turnaround).

Why? Because I’m over-delivering. And, this process can save your story, even before you write a word. It’s worth ten times the fee.

Get your order in at $100 before June 15 if you’d like to take advantage of the price break.

For now the $35 Kick Start Conceptual Analysis remains just that. More on this soon.

My Pseudo-2Q Newsletter Update With a Few Gratuitous But Nonetheless Valuable Tips is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 23, 2013

The Continuing Chaos of Concept

The challenge of this whole idea vs. concept vs. premise conversation is that anything can be regarded as a “concept.”

“I want to write a love story”… is a concept. It least if you don’t care about the differentiation between those three nuances.

Which you should, by the way, if you want to take full advantage of the story physics that are available to you. That’s the point, the reason you need to care about this.

This single thing can save your story. It can get you published. Because just as true is the fact that the lack of, or weakness in, a strong concept is perhaps the single most common story-killer out there.

Look up the word mediocrity, and it should say: “a story without something conceptual at its narrative heart.”

“A girl leaves home to find out who she is”… is a concept. It’s not even a story yet… but still qualifies as a concept from this more pedestrian context. And a weak one, by the way, but sadly, many newer writers begin and end with something just like that.

Differentiating idea from premise is easier than trying to jam concept into the equation. Premise adds a character and some implication of what that character wants or needs, what they will do in the story.

Premise is good. Necessary. And always better when derived from an underlying concept.

I’m not going to rehash the definitions of the three players in this debate: idea, concept and premise. Use the SEARCH function to the right of this post, it’s all in here.

But in an effort to illuminate and clarify… perhaps the better question – better than “what’s your concept?” – might be:

“What is CONCEPTUAL about your story premise?”

That particular context – turning the noun into an adjective – is more illuminating. It is precisely the solution to this problem.

Going to Disneyland is a concept. Going to Disneyland on a private tour with the ghost of Walt Disney… that is conceptual.

When the ghostly Walt asks for your help in finding his lost journal, hidden somewhere in the park and reveals the location of a hidden treasure… that is a premise.

Here’s an example, paraphrased from a story recently submitted to me for evaluation.

When asked to state the concept of the story, the writer said this:

When a young man overhears a plot against his country’s new king, he must choose between advancing his career to erase his family’s debt and saving his sovereign, all without coming to the attention of the religious sect from which he’s been hiding for years.

Here’s the problem, one that the writer – and perhaps many reading this – don’t perceive as a problem: this is a premise.

That’s all that it is. A premise.

Could you begin planning and writing from this? Certainly. But what, the agent or editor will ask, makes it remotely worth reading? What is inherently fascinating about this… idea… concept… or premise… pick the word that suits you, doesn’t matter.

What they’re really asking is: what is inherently conceptual about this story?

And so far the answer is: nothing at all.

In the casual, pedestrian, non-precise and non-professional vernacular of the unenlightened writer, or the cynical writer, this answer is also a “concept”… because from that uninformed context there is no difference at all between a concept and a premise.

Just like there is no difference between a person and a leader.

But there really is a difference… if it is your business to know there is a difference.

And when you grasp it, you add a powerful layer of compelling energy to your story… one that your premise may or may not have going for it already.

Read that writer’s answer again. There is nothing about it that is conceptual.

It’s just a story. With nothing that distinguishes it or even energizes it.

This story could happen in any place, at any time. To simply add “what if?” to the front end – often the empowering tool to find the conceptual layer of a premise – doesn’t do the trick, doesn’t save it:

What if a young man overhears a plot against his country’s new king, and he must choose between advancing his career to erase his family’s debt and saving his sovereign, all without coming to the attention of the religious sect from which he’s been hiding for years?

Does nothing to add concept to this premise. Big yawn.

So what would do the trick? Try this:

What if a young man discovers that the religion he has grown up with is more politically-motivated that it is spiritually pure?

That version is two things at once: more generic, and more provocative. It is an inherently interesting idea. It pushes buttons. It generates a tell-me-more energy… even though it actually reveals less about the story than the first version.

Because this is a concept… one that is not yet a premise.

It is something you can build upon. It is something that your premise can evolve from, and be stronger because of it.

The cynic asks, so what’s diff?

The diff is the recognition of where the emotional and intellectual juice of your story comes from. And then tapping into it in your story, beginning with your premise.

And thus the cynic remains unpublished.

I would say that easily half of the stories I evaluate have very little about them that is inherently conceptual. The “concepts” of these stories are really more a premise, but without an underlying source of compelling energy that stands alone.

A premise without a conceptual source of energy driving it is already at risk. Because it depends, almost entirely, on character and execution.

But when you add conceptual energy – an interesting notion, something that is compelling about it even before you invite a hero into the story – to character and execution, and have them responding to that… now you have something.

Now you have something that can get you published. Or will sell your screenplay.

Much like story structure, once you wrap your head around this the more you’ll see it in play out there.

Concept isn’t story arc. Not for writers who get it.

Concept is the source of energy for the story, it is emotional and intellectual fascination and magnetism.

It is the conceptual that we are looking for… something that stands alone as a compelling notion, something upon which you can build a story arc, with a hero, with a problem to solve and therefore a goal to reach, with something at stake.

What if you built your premise from a compelling notion that creates the stage, the context, for the story itself?

Now there’s a concept.

*****

Interesting in seeing how your concept and premise stack up? Click HERE and HERE for more.

The Continuing Chaos of Concept is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 18, 2013

“The Thieves of Joy” – A Guest Post By Art Holcomb

“Comparison is the Thief of Joy” – Theodore Roosevelt

Good vs. Evil. Right vs. Wrong. Love vs. Hate.

Luke vs. Vader. Werewolves vs. Vampires. Obama vs. Romney.

The Past vs. the Present.

The actual plot of “Lost” vs. whatever the Hell was going on there.

What it all comes down to is Opposition – the classic conflict within Life Itself. It is the basis for all perception and the very foundation of Story.

Because conflicts – the very building blocks of all stories – begin with a single comparison.

Whether it is a cool breeze on a hot, summer day or two armies rushing to oppose each other on a battle field, comparison exposes the differences between all things and, without it, conflict cannot exist. Duality exists in nearly every part in our lives and we enjoy the emotion of experiencing and embracing it’s inherent differences . All sports, warfare, love, art and human interaction stem from our ability and our inherent need to differentiate between things. With difference comes opposition and judgment about which is better – and with judgment comes the heft and weight of emotion that drives our stories.

The Taoist philosophers believe that the descent of man from his purest state began the moment that he started naming things as he sought to describe the world. It began with the simplest of distinctions, such as “Night” and all that is “Not-Night”, “Me” and all those that are “Not Me” and, most important (for motivational purposes), “Mine” and all that is “NOT-YET-mine”. From the earliest moments of life, we learn by comparing.

As a child of the 1960’s, I had a poster on my bedroom wall of a poem entitled Desiderata by Max Ehrmann, which went from being a minor work in 1927 to become a devotional for the Counter Culture Movement. While the piece as a whole is still worthy of daily contemplation, one passage serves our purpose here regarding the twin fundamental truths about comparison and human nature:

“If you compare yourself with others, you may become vain and bitter; for there will always be greater and lesser persons than yourself.”

This is Human Drama in a nutshell, and an essential truth that you must not abandon in your writing.

So . . . what does this have to do with Teddy Roosevelt?

As creators, we must all be thieves of joy, using the distinct differences and specific desires of our characters to produce compelling conflict.

Because isn’t this what story structure is about? The upsetting of the apple cart? The ruination of the serene?

Each “World-Before-Story” we create in Act I is interrupted by the Inciting Incident, throwing things out of balance, and the remainder of the tale is all about seeking that vital and illusive New Balance. In our finest moments, we force our heroes to spend all of Acts II and III finding a middle ground that they can – and must – live with.

But it isn’t all about the conflict. The power of contrast and comparison is at play in every step of the process. Let’s take Roosevelt at his word and explore the power of comparison:

(1) Through Characters – as we write, the differences between now and then, hero and villain, right and wrong must be eventually clear to the reader so that they can choose up their sides in the contest. What good is a hero that you cannot root for, or a villain to root against? Your characters are, at their essence, the embodiment of your different IDEAS, and the comparisons you create for them are the way of testing their validity in story form. The specific sides need not be clear from the outset, and must not be in certain genres such as mystery and horror, but the contrasts and the characterizations must be clear enough for the reader/viewer to recognize the differences between the individual players.

(2) Through Scene – each scene must be necessarily different from the next and inhabitable enough to really place the reader/viewer there alongside your character. The journey should be more of a cross-country drive – with many distinct and unique stops- than an airplane hop across country. You need to sit inside each scene for a while and look around and truly get to know the place before you write. Remember: you took your characters here for a reason – make the most of it. And make sure the locations have a character of their own as well and, through your descriptions, their own personality.

(3) Through Dialogue – make sure your characters truly sound different as they speak. Do this by learning about speech patterns, rhythm and cadence. Do not resort to accents or caricature to get this across. Few things are worse than hokey dialogue that the reader must stumble through or the viewer must rewind to understand. Seek to write roles that are natural but different enough from one another that you could tell them apart without attribution.

(4) And through Your Own Voice – your work will be compared to others. It has to happen in order for you to gain a following. Sometimes it seems that Hollywood and Big Publishing are merging into one great, shambling beast, and even as they cry for new and different voices, they continue to produce books, films and TV that all seems the same. Certainly, the marketplace loves to homogenize through their notion of “the-same-but-different” so that financial risks can be minimized, but that must mean little to you in the privacy of your own creating. Always give them something that can only come from you, and keep refining, improving and submitting until they finally “get you”. It may take a while longer than pandering to the common denominator, but you’ll smile more often in the process.

By showing the reader/viewer the distinct nature of your characters and their world, we increase their ability to identify with your creations and your art. How well you use comparison and contrast in your writing dictates the power of your work and the efficacy of your message.

Until next time, don’t stop.

Never Stop.

Art Holcomb is a screenwriter and comic book creator. His most recent comic book property is THE AMBASSADOR and his most recent project for TV is entitled THE STREWN.

“The Thieves of Joy” – A Guest Post By Art Holcomb is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 14, 2013

Left-Brain, Right-Brain, or No-Brain At All

We’ve heard the phrase: it’s a no brainer. Writing a story that works is the absolute opposite of that.

So let us attempt to put a fence around, if not quite sequential-ize or formula-ize, the nature of the successful storytelling process.

It all breaks down into three unique but dependent phases of story development. The key word there is dependent… because they are, in the final analysis, sequential. And thus, if you begin in the middle, the task is complicated by the process you’ve chosen.

Somewhere along this path – you get to decide where and when – the process evolves from three-by-five cards and yellow sticky notes and flowcharts… towards leaning into and finally becoming the act of drafting itself.

Which means if you start there, you need to know that you don’t get a free pass on the preceding development part, that you are creating the recipe while you are cooking the stew.

Not saying it doesn’t work, it does. For some. We all get to choose. At the end of the day it’s all story development.

Either way… the process is both iterative and evolutionary.

Blank spaces in your flowchart (or in your head) become bullets which become phrases that turn into sentences that expand into paragraphs… that sometimes without realizing it, are suddenly full-blown scenes. And then need to be blended into the whole, in context to the scenes that surround it.

Or you can do it backwards. Scenes pop into your head, then you retrofit a mission and that all-important context.

Or not. That being the source of a huge percentage of the rejection slips out there.

You can throw it all into a pot, stir it and heat it to boiling… or you can impart it all to a blueprint with the anal-retentive precision of a computer programmer under a deadline… or some combination in between… doesn’t matter, because the end-game is what it is, and that high bar is both blind to and oblivious to your chosen process.

The Three Realms

At any given moment in the storytelling process, you are either in:

1. The conceptualization phase…

2. The sequencing and execution phase…

3. The revision and polishing phase.

Yes, we do bounce back and forth. And it’s a good and normal thing to do. But, like a marathoner who at any given moment is either swimming, biking or running, knowing the difference is fundamental to the game being played.

Conceptualization Phase

The conceptualization phase (which I’ve also dubbed the Search for Story phase) is the creative dance between story idea, story concept and story premise (each being a different animal), leading toward a general story landscape and a compelling core dramatic question – where character and conflict collide – that can be pitched in a few lines in a manner that is compelling. It’s what the story is about, without short-changing it.

In 99.9 percent of the cases in which the writer, when asked “what is your story about?” gives an incomplete or less than compelling DRAMATIC answer (like: “it’s about the effect of poverty on taxation…”), or says, “well, it’s kind of complicated…” this is a symptom of a writer still dwelling, perhaps swimming in, the initial story conceptualization phase, usually without realizing it.

Moving on, and then settling — executing a story that hasn’t fully experienced the Search for Story phase, lead to a killer core dramatic question — is seductive. Yet, itt is the Great Killer of stories.

Let me repeat: until you’ve nailed your core dramatic question, or what that even means, you haven’t got a story.

Sequencing and Execution Phase

The story sequencing and execution phase is, literally, plotting it out in the order of narrative presentation, strategically setting up, exploring and resolving the core dramatic question through your characters.

This is when we identify the major story beats, in context to what we know from the initial conceptual phase planning (the search for story), and put them in the right spots, and then coming up with bridging story points that connect them. It’s literally the identification of scene content, driven by (when done properly) the contextual mission of the story beat you’ve chosen for any given moment.

Consider this. In fact, paste this on your monitor:

This is where dramatic arc and character arc become one in the same, and do so within the context to a fully developed conceptual story landscape.

If you want to break this down even further… the search for story includes finding the right sequence in which to tell it. And when you’ve done that, via outline or draft, only then are you executing the story you’ve found. Both of these are part of the second phase of story development.

You cannot search for story and execute the story at the same time. Any more than you can hunt the goose and cook it at the same time. Anybody who claims to do so – and they’re out there, some of them quite loudly – is really talking about revision and execution.

Read those last three paragraphs again.

Because right there is the 404-level understanding that many less experienced writers don’t get. It’s one of the keys to writing publishable fiction, and it’s a loaded sentence.

Either way, whether it’s in an outline or a draft, when that happens you’re on to the third phase.

Revision and Polish Phase

Once on paper, you need to optimize what you have through revision and polish. If your outline is solid, you won’t have as much challenge here as you will if you used drafting to get to this point.

In that latter case, the line between searching for your story and executing it is often a fuzzy one. And it’s a line over which many writers get tripped up.

If you’ve outlined it, and you’re happy with the outline, it’s time to write the first draft, moving from search to execution. If you’ve reached this point through drafting, it’s time to revise (as part of execution) and then polish it.

This is always true: the more you know about your story, and the more criteria you bring to it – however you get there – the closer to the finish line you will be. Understanding where you are in these three phases of story development is the most empowering thing you can do to get there… safely.

****

Click HERE to see where your story currently resides on this three-phase story development path.

Left-Brain, Right-Brain, or No-Brain At All is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 3, 2013

Bold Storytelling Statements That Are Almost Always True

A great concept is the raw grist for a great premise. Not necessarily the premise itself.

Idea… concept… premise… for writers these are separate and essential things. Unless they aren’t separate (an idea can arrive in the form of a concept and/or premise). Which rarely happens.

The order in which they arrive is not set in stone.

Premise evolves FROM a concept… even when it begins the other way around in the writer’s head. The risk is to hatch a premise that does not connect to an underlying concept that energizes it.

Example of a premise without a concept: guy falls for girl on a space station, where they are the only two inhabitants.

Example of a concept that is not yet a premise: what if two people assigned to a space station are both a human clones but neither one knows?

Story very close to that: Oblivion, in theaters now.

Concepts can be arranged hierarchically. Go deep enough and you end up with a premise.

Fail to go high enough and you leave dramatic opportunity on the table.

The most common weak link I see in the story deconstructions I do: a misunderstanding of what the phrase “dramatic tension” means, and a resulting lack of it in the story.

Great stories always have external tension that become the fodder to make internal tension transparent.

External tension drives story architecture.

Plot is not a dirty word. It is synonymous with dramatic tension.

Show me a story with no plot and I’ll show a short story, or an unpublishable novel.

The concept acts as a “battery” that fuels the premise and the narrative itself with energy. The concept is not the appliance itself, it is the electricity that runs it.

A rich concept can yield multiple stories, or multiple takes on an obvious story.

You really can’t hope to turn a concept-light, tepid premise into a great story through stellar execution. A cow’s ear is still a cow’s ear, even in the shape of a silk purse.

The Hunger Games, without the games, is just another teenage love story.

That said, a story that is concept-light but strong on premise (example: The Help) can be twenty million copies worth of wonderful.

Premise is like personality: hard to define but you know it when you see it.

The most common storytelling mistake is an under-cooked premise.

“Story” is a relative term. Not all of them are worth telling.

Your lyric, poetic, brilliant writing voice… it’s never the point. In fact, it can kill your ambition if you think it is.

You can’t reinvent this game.

Some claim there are no rules, but there certainly are one helluva solid set of principles driving how you write strong fiction. Depart from them at your own peril.

Plot is the stage upon which character is allowed to reveal and explore itself.

Developing a story on autopilot is the enemy.

Paranormal abilities should never be the thing that solves the crime in a story.

Don’t kid yourself, it’s been done before. So what’s your fresh twist?

When a major story beat involves the hero “suddenly realizing” something… that’s a bad sign.

“Write what you know” is good advice. Write what you love is better advice.

Reading novels is not a particularly empowering way to learn to write novels.

Never underestimate the power of vicarious experience delivered to your reader. Give your readers a ride.

The more you do it, the closer you get to it, the less glamorous and more blue collar this storytelling gig becomes.

Settling is the great killer of stories.

Narrative side trips are a close second.

Changing lanes is next. If your murder mystery becomes a ghost story on page 214, see the next statement.

If you pants your story, then discover it becomes something other than what it began as, you absolutely need to write a new draft that uses the new context from page one.

Not knowing what makes a story great makes the whole thing a crap shoot. Somebody will eventually win the lottery using random numbers.

Many of the novels on the bookshelves are not as good as the one you wrote and cannot sell.

Self-publishing is a new, unproven frontier. One that hasn’t fully evolved. And one that brings unforeseen risks, because traditional publishing at least provided an infrastructure to vet the work. That’s why Youtube won’t ever compete with the films we pay money to see in theaters.

There are more multimillion dollar success stories coming out of traditional publishing, even today, than the ones you hear about from the digital self-publishing world. The odds of a jackpot are no better on Amazon.com.

Do not copy the way A-list writers go about their work… they have a different bar, and it’s lower than ours. (Look at the way Nelson Demille — one of my favorite authors — decided to end his #1 bestseller, Night Fall… if we tried that we’d get laughed out of the mailroom on its way back to us.)

Deus ex machina — look it up. Then avoid it in your stories.

I am sometimes drastically misunderstood.

The word “troll” has been completely redefined in the last ten years.

All writing lessons are good, except one. Listen to it all, pick what you like. Soon your wall will be full of what sticks.

The one that is not good: if you don’t know anything about what makes a story work, don’t worry, just put your butt in a chair and start writing, it’ll come to you eventually.

If you live long enough.

The knowledge is out there.

You may or may not pick it by being a voracious reader of fiction. Probably not.

Process does not define story. It does, however, define the amount of blood required to write one that works.

Suffering is optional.

Coincidence may happen in real life, but it can kill your story. Usually does.

So which comes first in “romantic suspense,” the romance or the suspense? (Wait, that’s not a statement…)

Literary novels need conflict, too.

Literary fiction leans into conflict that resides internally to the character, something that becomes the core story and the foremost challenge to the protagonist. Literary novels are NOT plot-free. Structure, stakes, pace and story physics are still required.

To the guy on Amazon who said he wants to come to my house and throw books at me: I’m still waiting for you show up. That’ll be fun. But not for you.

“The Adventures of X” story is the hardest of all to write at a publishable level.

Setting, time and place are planks used to construct a stage, hammered together with ideas. But you can only look at the stage for so long before you long for something to happen, and the nails need to be solid. Solid what? Answer: hero-driven drama. And when you add that, the story is no longer primarily about setting, time and place.

Stories that explore a time or place or culture as the primary intention of the author are… usually boring.

Episodic storytelling is almost always a story killer. There is only one kind of story in which that works, and it’s the hardest type of story to write.

It’s a dead heat in the race to win the title of “most important word in fiction,” between conflict and context.

Meanwhile, subtext can make or break you.

A good novel is rarely – as in, never – the life story of a fictional character. (See above, on episodic.)

One of the most toxic, misleading sources of writing guidance for newer writers is the language of book reviews. A “novel about the depression,” for example (which is how reviewers might frame it), doesn’t begin to define what the novel has to cover to work. Example: The Great Gatsby.

“Show, don’t tell,” is golden. Unless nothing happens in a particular transitional story beat (like a time shift forward)… then just tell it.

Your high school writing teacher was wrong about a whole lot of stuff.

First person narrative is not only okay, it’s hot.

Mixing first and third person… perfectly fine, IF they are never mixed within a single scene.

Your high school writing teacher is rolling over in her/his grave right now.

I do mishandle the word deconstruction. Deal with it.

There has never been a successful final draft written without the writer knowing how the story will end.

There is only rarely a first draft that ends precisely as the writer thinks it will.

You can – it’s entirely possible - nail your story in two drafts (1.5, draft and polish)… IF you understand what you’re doing from a story architecture perspective, and at a deep level… if you let this drive your story discovery and planning process.

Conversely, if that doesn’t happen, it doesn’t mean you don’t know what you’re doing.

Paradox, I think they call it. A wonderful word for writers, and about writers.’

The journey may or may not be the thing.

The trick isn’t to write ABOUT something. The trick is to write about something HAPPENING.

Key words from the title of this post: almost always.

Bold Storytelling Statements That Are Almost Always True is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

April 29, 2013

Three Workshops and a Blog Post

“Strive for perfection. Settle for excellence. ”

(Don Shula, football player, coach and restaurateur… who knew there is no “n” in that word?)

Ask and ye shall receive. Sometimes.

One of my goals today was to come up with a worthy Storyfix post. I was jonesing for something with intimacy, a little one-on-one commiseration – it’s been a while - but thought-provoking.

And there it was, in my email inbox.

Quick backstory: I’m teaching three workshops at the Willamette Writers Conference (August 2 – 4, Portland OR… it’s a massive affair with a wing full of agents and some really killer breakout sessions, please check it out). In preparation for promo and program materials they asked me for a short description of my sessions. Of course, I ignored the “short” directive and pounded out three missives… which were distributed today to participants via email.

Which brings us – me – full circle to today’s post. Hopefully some morsel will stick to your writing wall in the form of something… useful. It’s good to go Big Picture now and then.

****

“Beyond Craft… Embracing Greatness” — read the blog post here (from the Willamette Writers site).

Session Descriptions

FRIDAY 8:30 -10:00 (double room) – STORY PHYSICS 101

Writing salable fiction is a full circle proposition. We begin wanting to touch lives, maybe change the world, and to do it with high style. We yearn to reach our readers as we entertain and enlighten. And so we immerse ourselves in craft, learning about structure and voice and the nuance of character, applying trial and error informed by workshops and books and the collective wisdom of a closet full of critiques and rejection slips. Maybe we reach a point where we believe we “get it,” or maybe that journey continues… it’s usually both. But at some point we return to that initial intention, armed with our learning curve but still relying on instinct to create stories that work. This workshop will offer a peek behind the curtain of craft into the realm of Story Physics (where that instinct awaits), the forces and essences of cause and effect that move readers toward a state of total immersion and emotional resonance.

SATURDAY 8:30 – 10:00 (double room) – CHARACTER VS. PLOT

Welcome to the eternal dance between character and plot, sometimes disguised as trade-off or debate. When done properly, it becomes a narrative union that becomes a sum in excess of the parts. Great stories blur the lines between character and plot, making each both dependent upon and expansive of the other. This workshop will use well known examples (books and films) to demonstrate this critical codependency within the context of expositional (sic, and deliberate… sometimes the best word isn’t really a word at all…) creation, identifying and avoiding traps that can cause a good idea to under-achieve on the page.

SUNDAY 8:30 – 10:00 (double room) – FIX YOUR NOVEL WITH ONE MORE DRAFT

Nobody expects a first draft to work at a salable level. Beyond that, though, the number of drafts required before you can legitimately stamp “FINAL” on it depends on three things: what you learned from and about that first draft… in context to what you know about what the story – any story – ultimately requires… and the process by which you evolve it toward that benchmark. This workshop delivers criteria, targets, benchmarks and reference points that apply to all drafts of a story, and will show how their integration and implementation – it doesn’t have to be one step at a time, draft after draft – is what charts a path, and the number of pit-stops, toward that destination.

*****

If you’re connected to a writing conference, or you are looking for a presenter for your regular meeting and/or private writing soiree, and some of this sounds like juicy good fun to you, contact me at storyfixer@gmail.com.

Three Workshops and a Blog Post is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

April 25, 2013

The Psychology of Story Physics

There are writers — some who claim to know, others who simply don’t know — who aren’t buying into the notion of a “first plot point” as a useful or even necessary story milestone. Those who believe that an earlier inciting incident is sufficient, wherever it appears, and that a gentile dramatic slope from that point onward will suffice.

What these people are missing is an awareness that the human mind thrives on figuring out life experience in a manner that aligns with the principles of story physics, including a moment when “everything changes.”

Which is the reason the FPP exists.

A story without proper, optimized story physics – on this and on other levels – feels flat. Because we, the humans reading it, are not drawn to it (empathy and vicarious experience, also elements of story physics) at a basic psychological level. It’s like food — if it smells bad, or simply doesn’t smell good, we aren’t as hungry.

Story physics aren’t random suggestions. As Larry suggests, they are natural law. The reasons they work align with the reasons we’re alive in the first place — to discover, to experience, to learn, and most of all, to feel.

And when we feel, we adapt, and we survive.

And so it goes… our stories contribute to life itself.

For example, one can only completely experience water by getting wet, drinking it, swimming in it, using it, and in the extreme, drowning in it or even dying of thirst. These are all experiences, things we can relate to emotionally even by simply imagining them, without actually going through them. When a story delivers a heightened level of perception (the realm of vicarious experience), we experience it on a level that becomes intimate… and thus, the story works.

And you, the writer, have just tapped into the psychologial power of story physics.

The six realms of Story Physics provide a framework to understand what we are experiencing, and thus attract us to a story that delivers them.

Say you wanted to understand the circle of Victim-Victimizer, which is a life principle that touches us all.

Those two words — victim-victimizer — are one and the same. The Victim refuses to be responsible for themselves, regardless of what the cost. For example, a “victim” decides to go hiking without wearing the proper attire to protect themselves from the elements and, due to a late spring snowstorm, freezes to death in the mountains. Let’s say the victim was ignorant of late spring snowstorms. Okay, maybe, but did the victim seek to learn about mountain weather before going hiking, or just decide to wing it? This is what the people at the funeral will think about, and perhaps the victim pondered up until the moment of his death.

Maybe even after that, too… a story we have less empathy with because, well, nobody can say what that’s like.

Note how Story investigates at least part of what the victim will ponder up until his death and what the funeral attendees will be wondering. Story trumps real life in that regard… in a story we get to do it right, or at least to strive to understand where and why it goes wrong, without actually suffering.

The above example may not be the most elegant, but it should show that a Story has a mind of its own and the Story Mind is working to resolve things as if it were an advanced consciousness, using different “characters” to play different roles to figure things out.

This is the psychology that makes vicarious experience — one of the six realms of story physics — so effective. And why empathy is the stuff of bestseller.

I’m not alone in these thoughts. The creators of Dramatica said this very thing regarding the Story Mind.

The storytelling options in this regard are wide open.

To dismiss a proper FPP by claiming that the story “started” on page 4 is to not mine the gold of the story physics involved. Or get confused in a jungle of jargon and rhetoric relative to story structure.

Let’s say you and I were at the funeral of poor Bob, who died of hypothermia on that mountain. How far back in time will we go in discussing Bob’s predicament in order to make sense of it? That’s the key when it comes to storytelling. For Bob, there was the point in time that he was too far up the mountain to make it back before he froze to death… what did he do in order to try to survive in that moment? How did that moment of realization feel? The moment when everything changes, and now you must respond to the new problem before you.

That would be the First Plot Point in Bob’s tragic story.

Let’s say the searchers that found Bob said he back-tracked the way he came but he either ran out of time, or it got too dark and he fell down a ravine and was too weak to get out. The obvious question now is: why did Bob go out without adequate clothing in the first place, and did anyone see him before he headed out? In trying to make sense of it, we’re going farther back in time, BEFORE the FPP in order to figure out and make sense of Bob’s FPP.

Why? To tap into story physics. To enhance our empathy. To make the vicarious experience more visceral. To feel the dramatic tension of it. To ride along (pace).

To me, anyone saying their story starts on page 4 just doesn’t get what a story really is, and without story physics on their side it will be hard to enlist the reader at the emotional level required.

Shakespeare said, “what’s past is prologue.” Amen to that.

Life is about making sense of experience and the feelings that attach to them… and taking that understanding with you.

Ultimately, so are stories.

The Psychology of Story Physics is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com