The Secret Weapon of Story Physics: Narrative Strategy

A story is always the sum of – the outcome of – a huge pile of author decisions: where to start, how long, how soon, how to end it, where to end it, what not to end, how much, how little, when to show this, when to say that…

… all of it, hopefully, arriving in context to some basis for the decision itself… for an informed notion of why.

The basis is often simply your gut instinct. Good if you’ve got one. Even better when driven by a grasp of storytelling principles and physics and a few tries under your creative belt.

Too often, though, as you stare down the barrel of a new story, the basis for these decisions is caught wandering somewhere between the first thing that comes to mind, comfort level and casual randomness.

No matter how you decide, or what you decide, there is always one other choice – a different kind of choice — that looms even more urgent than what-goes-where.

The most visible decision you will make is your narrative strategy.

Because you really can’t write a decent word, not a single paragraph with ambitions of being in its final form, until you decide upon narrative strategy.

What is narrative strategy?

It’s how you will narrate your story. It is the voice of your story.

Pretty much everything else you need to decide upon defines the WHAT of your story. The expositional content of it.

Narrative strategy, along with structure, leads you toward the HOW of it.

Structure is the sequence of your story’s unfolding.

Narrative strategy is the actual mode in which you tell it.

And, like a singer’s tone or a painter’s technique or a State of the Union address’s political context, it is critical to making it all work.

If you think of your story as a journey from point A to B, structure is the route taken. The order in which information is delivered to the reader.

Narrative strategy is the vehicle in which the reader will ride. The contextual means of the delivery itself.

Who is telling your story? The hero? The hero’s neighbor (think “The Great Gatsby”)? A few folks? God, or some omniscient, all-seeing voice?

And then… how are they/he/she framing it all?

Your story’s ultimate fate may rest on this one single decision more than any other.

The Default Narrative Strategy

The most common voice of a story, the one we were taught first back in the day, is third person omniscient narrative. The “god-narrator” perspective.

Bob walked to the ledge and looked down, seeing nothing that would change his life, as he’d feared.

It allows you to look anywhere and notice anything, including what a character is thinking. It even allows you, when handled correctly, to know what others are thinking in the exact same moment.

Because the god-narrative knows all, sees all, and may or may not tell all.

From there you can, within this constraint, narrowed the point of view to create intimacy, nuance and detail:

Bob walked to the ledge, conscious of a sea of eyes following him, his stomach churning at what he feared might be a moment that would change his life forever.

About the only hazard on this narrower road is point of view… like First Person narration, “tight” third person demands that you not mix multiple points of view within a given scene.

Third person, in all its common forms, is the one your high school creative writing teacher told you was the proper way to tell a story. In some cases, the only way.

That particular piece of advice is in the running for the worst, if not the most out-dated, writing advice dispensed in the last one hundred years. Tell that one to Holden Caulfield and Mike Hammer and a girl named Katniss, among a few hundred other literary iconic heroes. If you’ve read a bestseller lately, you’ll know that conventional wisdom has long since been debunked.

First Person Narration

Perhaps as much as half of the novels being published today are in First Person.

I moved slowly to the ledge, locking a death grip on the railing before allowing myself to look down, wondering if this would be the moment my life changes forever.

In a given moment the reader is privy to what the character is seeing, feeling, perceiving and feeling, in a way that is less constrained by logic and colored by world view and backstory. It is the quickest and clearest route into the mind of a character, often including humor, irony and some hidden darkness that only the reader sees.

In my view, First Person becomes the default choice for stories in which an interpretation of the unfolding exposition is the focus of the story. First person marries nicely with another of the Six Realms of Story Physics – the delivery of a vicarious experience.

And yet, some writers remain wary. Could be comfort level, could be lack of confidence. My advice: try it out. You may immediately realize you’ve found your default voice. That you’ve arrived home.

That’s precisely what happened to me. It was at that moment of decision that my writing career took a turn.

The First-Third Combo Meal

Point of view is a force of nature, it demands a singular scene focus without compromise. And yet, the choice of First Person narrative as a strategy comes with a price – you cannot show what takes place (either in the past or present) from beyond the limits of the narrator’s scope of awareness.

And yet, many stories depend on such behind-the-curtain building of suspense and the means toward the confluence of story forces.

What to do?

Make your high school writing teacher roll over in her grave by combining the two within a story. Actually writing scenes that come from one or the other voice – first or third – that show the first person narrators perspective, and the elsewhere perspective, as required… in the same story.

The only rule: never do this within a single scene. Either create a new chapter, or skip lines to define a scene shift, whenever you switch from first to third, or third to first.

If this is your approach, make sure to give roughly equal time to both voices, and use the device strategically to build suspense and manage pace. You’ll quickly find you have a lot to work with in those regards.

I first saw this done in Nelson Demille’s “The Lion’s Game” and then it’s sequel, “The Lion,” and it blew me away. It impressed me to the extent that I did it in my own novel, “Bait and Switch,” and in every novel I’ve written since (my new novel, “Deadly Faux, “ out in October from Turner Publishing, employs this narrative strategy.

It’s out there everywhere. Another arrow in the quiver of narrative strategy.

The goal is to find your best voice, rather than settle for default choice.

The Enhancement Choices

First versus Third Person isn’t the only choice on the writing table. The writer must also elect either past tense or, in an emerging trend, present tense.

Third Person Present: He walks to the ledge and looks down, seeing nothing that will change his life, as he fears.

First Person Present: I move slowly to the ledge, locking a death grip on the railing before allowing myself to look down, wondering if this will be a moment my life changes forever.

Suzanne Collins used First Person present in “The Hunger Games” series, with great effect. These stories read much like a screenplay (that’s no accident, all screenplays are written in present tense), adding to the sense of vicarious immersion and experience.

But notice how, in those books – unlike the films – you see nothing that Katniss cannot see. It’s no accident the movie did it differently, creating added tension by allowing the viewer to understand the emerging danger before Katniss herself does.

In Kathryn Stockett’s mega-hit “The Help,” she went even further out on the strategic limb with this choice: she has three different First Person (past) narrators. Each occupying the role of protagonist/hero, and each integrating with the others. Many scenes have two or more of the characters involved, but always within a consistent narrative point of view for the scene itself.

These choices comprise a matrix of options for your consideration. First or third? Past or present? Mixed person, or singular? Multiple narrators with a consistent voice, or multiple narrators from both first and third?

You get to choose. The question is… how?

The Challenge of Choice

This is a challenging proposition. I’ve read many stories in my coaching and evaluation work that would work better in First Person, which is a tough piece of feedback when the writer has already written 400 pages in Third Person.

Much better to get this right before you begin the drafting process.

The key to the optimal decision is your understanding of the potential and limitations of each strategy, merged with your understanding of the dynamics of the story itself.

With a touch of comfort level thrown in.

How much exposition takes place outside of the scope of your hero’s awareness?

Whose story is it? How many points of view are there?

How personal is the story? How important is getting into the hero’s head and experiencing that chaos, emotion, elation, and the confusion of not knowing what things mean?

Does your story rely on wit? Humor is much easier when it comes from the head, and the lips, of the narrator.

Where is the dramatic tension coming from? How much does the hero know, or need to know, about that information?

I don’t think there’s a hierarchy of criteria that lead you to this particular Narrative Strategy choice. I believe you need to trust your gut. Which means you need to develop your gut instinct, whatever that takes. And, perhaps do a little research to see how other novels with similar premises and qualities to yours (yes, they’re out there) have been handled.

At some point you’ll know. Hopefully sooner rather than 400 pages later. You’ll know because, from an informed context, it’ll just feel right.

That feeling with either lean toward random and uniformed, or take-it-to-the-bank supported by basis for your decisions.

And thus are made bestsellers and rejected manuscripts. We live and die by our feel, our instincts, and the database of storytelling knowledge that informs them.

The more you know about your story, and the earlier you know it, the more optimal your choices will be.

******

Narrative Strategy is one of six key realms of Story Physics… as defined in my new book, “Story Physics: Harnessing the Underlying Forces of Storytelling.” Available now, online and in your local bookstore (after June 18).

*****

Have you ever wanted to kill your writing teacher? Hmmm….

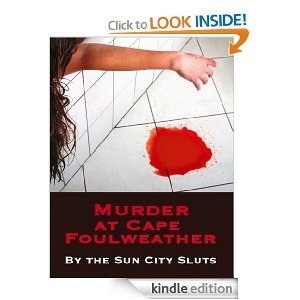

A few writer friends have just published a fun new mystery called, “Murder at Cape Foulweather (A Sun Slut Mystery)“… if that doesn’t foreshadow the tone, nothing will. It’ s about a weekend workshop with a writing teacher from… wait, no, it couldn’t be… they swear it isn’t… anyhow, it’s a story full of secrets and sex and, I assume, a dead writing teacher. Sounds like fun. These women are really good, and really funny, so it’s worth a look. Already have my copy, and I’m hooked. Hoping you’ll check it out.

The Secret Weapon of Story Physics: Narrative Strategy is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com