Larry Brooks's Blog, page 27

August 27, 2013

Do ‘Story Physics’ work in Fantasy?

An interview with A-list sci-fi and (now) fantasy author Kay Kenyon.

Kay’s new novel — her first fantasy after a string of highly successful science fiction titles — is just out. It’s called A Thousand Perfect Things, I’ve read it, it’s stellar.

This interview puts Kay Kenyon on the firing line for her claim that she always uses the principals of story architecture and story physics for engineering a story. This can be risky, because in execution most authors adapt this stuff to an extent that they are no longer recognizable. After reading the story, however, I think what she has to share on this topic is of value.

So we’re going to take her brand new historical fantasy and deconstruct it without giving away too much of the plot.

How can we do this? Veeeery carefully.

Larry: I read an advance copy of the book, and I loved it. One thing I’ve gotta say–apropos of this post topic–the plot is really out there.

Kay: It is. The story treats with magical terrorism, love, mutiny, Victorian repression, the British Raj, silver tigers, kraken, ancient ghosts, a bridge across the ocean and palace intrigues in the court of a rana.

Larry: So boil down the concept. Pitch us.

Kay: What if a young Victorian woman, denied access to the halls of science, decides to use forbidden magic to make her mark–and to do so must cross a great oceanic bridge to an altered India of magic, thereby taking on the Raj, a mutiny and the impossible quest for perfection?

Larry: Complicated, and very compelling. With all that complexity, the story might have come apart at the seams (scenes?) if you didn’t nail it structurally. Did it hold together during the drafting process? Notice any difference in applying the principles in fantasy versus your sci-fi wheelhouse?

Kay: Story structure is needed as much in fantasy as in any genre. Plot milestones keep a fantasist on target.

Larry: I definitely saw story engineering at work in A Thousand Perfect Things. For example, Plot Point 1. I’ll let you tell it: Where is the point where the hero’s quest (in this case, Tori Harding’s) is defined–in context to an antagonist force?

Kay. On pages 48-53.

Larry: A little early, perhaps?

Kay: Agreed. But I’m pleased with the work that scene did. It was also the inciting incident. The regiment is going to the land of magic, and Tori–previously beaten down and hopeless–sees a fortuitous chance to insert herself in the enterprise. She crosses over a bridge to the magical world determined to own the magic properties of a certain object.

We know what she has to gain or lose: her desperate desire to thwart her enemies and be recognized in her scientific field. She will seek a mysterious source of power that will break open the closed ranks of male scientific culture. If caught, she knows she’ll be hauled back home. But really, death awaits. . . as we’ve seen from the antagonist by this point.

Larry: That was a critical scene… the approach to the bridge, with it’s bizarre properties, the regiment setting out. But your best use of the major plot points, I believe, was the midpoint.

Kay: I think so, too. This was on page 157-164, a sequence of scenes that reveals the missing piece of information hidden by a conspiracy. Tori has been a wanderer in Part II, responding haphazardly to opposition. At the midpoint, higher stakes are revealed, and she becomes a warrior in pursuit of her quest. She must become a fighter, because she’s now pursued by a calamity.

Larry: So in your 300 page book, you are spot-on in the delivery of a scene that shifts the context of the conflict. And it’s a doosey.

Kay: The midpoint scene reveals a context that the reader has known. The reader watches Tori as a wanderer, saying wake up, wake up! Now she does, because of new, horrifying information.

Larry: I’d really like to tell what happened, but…

Kay: I’d have to kill you.

Larry: Well, it would be too late, but let’s move on to Plot Point II. That was a scene that I can imagine being a trailer in a movie.

Kay: Me too, let us hope! Any inside contacts?

OK, so on page 207, at 67% into the story, we hit Plot Point II. A a few beats early of the 75% ideal. In this scene Tori has a life-altering experience. Major spoiler here, so all I can say is Plot Point II changes her forever. It’s a major reversal.

Larry: The next few scenes unravel that new information and give it meaning, so this plot point is more spread out than others. But the job is accomplished. I’m starting to be a believer. You’re using these milestones, even amid the magic.

Kay: Hand-waving and winging it never works. Not even in fantasy. I planned for Tori to receive the last piece of the puzzle at this point. Everything in the novel drives toward this scene.

Larry: But you flipped things. Sometimes what the hero thinks they wanted isn’t it. That’s tricky stuff. But the plot still pursues the same thing, only now it’s in a totally different context. Meanwhile, the stakes build even higher.

Kay: Even though I flipped the goal, I still have to show that what the hero now wants is worth all the build up. Tori becomes a a true hero/martyr in pursuit of her goal, even though an altered goal, one intertwined with her original quest.

Larry: And now for the final act. Where does Part 4 begin?

Kay: When the heroine knows the thing that she has to sacrifice, and has changed enough, conquered inner demons enough, to do it. She marches into the hands of her enemies. But she has a secret strength. It may save her, but she can’t count on it.

Larry: The ending was tricky, though. It was a time of war, and though it had been building, did we lose sight of what we were after?

Kay: The ending is complex. Tori makes a fateful choice that reflects the resolution of her inner conflicts. It plays out against a tidal wave of events that has been approaching throughout the book. Although Tori does become a minor player in this disaster, she is the driving force in her own transformation. And she enters the larger fray a mythical figure. Guns are trained upon her on the beach. . .

Larry: Stop there, no spoilers allowed.

Kay: I worked to give the final pages an emotional punch. Tori has one last thing to decide. It happens on the last page. I think the reader will feel it viscerally. I hope satisfied.

Larry: I appreciate you sharing your journey with us, and providing a real-life example of what happens when a proven pro like yourself proactively applies story architecture to an already potent story landscape.

One of the best ways to learn these principles is to see it applied. Which makes A Thousand Perfect Things a clinic for writers, as well as a deliriously rewarding ride for readers.

*****

A Thousand Perfect Things is an epic tale of magic in a re-imagined England and India, when a Victorian woman takes on the scientific establishment, place intrigues, ghosts and a great mutiny–by marshaling the powers of magic. Now available in trade paper and to pre-order in eBook. Pub date: August 27. For a limited time, the eBook is offered at a special price of $3.99.

This is Kay Kenyon’s first fantasy after ten novels of science fiction.

Twitter: @KayKenyon, Facebook: Kay Kenyon, Author or her website: www.kaykenyon.com/novels

*****

This is Kay Kenyon’s first fantasy after ten novels of science fiction. Connect with her on Twitter, FaceBook or her website.

Do ‘Story Physics’ work in Fantasy? is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

August 23, 2013

How to Create Layers of Thematically Pertinent Conflict

A Guest Post by K.M. Weiland (@KMWeiland), author of “Structuring Your Novel”

How many times have you heard that conflict is story?

This truism powers all of fiction for the simple reason that conflict creates plot. Your protagonist wants something. Someone prevents him from immediately gaining that thing. Conflict ensues, and a story is born.

On the surface, conflict is a ridiculously easy concept. Have one character punch another. Or yell at him. Or even just give him the silent treatment. Easy-peasy, right? And to some extent, that’s true. As long as you have an antagonistic force that is preventing your protagonist from getting his grubby little mitts on his overall story goal (and the individual scene goals in between—both of which I discuss in way more detail in my book Structuring Your Novel: Essential Keys to Writing an Outstanding Story), then you have enough conflict to drive your plot.

But if you want to take your story to the next level, then you’re going to want to not just generate a simple round of one-on-one conflict. You’re going to want to take it to the next level. You’re going to want to layer the conflict among multiple characters.

Selecting your story’s antagonists

How do you know which characters should be your story’s antagonists? To begin with, let’s just stop and clarify that an antagonist is not necessarily a bad guy. An antagonist is anyone (or thing) preventing your character from getting what he wants. A scene’s antagonist could be the nice little old lady your protagonist has to take time to help across the street before he can go catch the escaping bank robbers. The story’s overall antagonist could be the character’s mother, who wants him to go to college instead of hiking around the world.

So when we start talking about people who are opposing your protagonist and creating conflict, we’re not necessarily talking about super-villains with squirrely henchmen. What we’re talking about is a person who has a legitimate reason to oppose your protagonist’s wishes—and who has the muscle to be a formidable threat. It isn’t enough for a character to disagree with your protagonist; he has to have the ability to block your protagonist’s best moves.

Once you’ve got your main antagonist in the bag, you’re then going to want to identify at least two minor opponents. These folks probably won’t have quite as much muscle as the main antagonist, but they will also oppose your protagonist on some level. And they’re going to be just as tenacious and annoying in holding him back from getting what he wants. For example, if your main antagonist is a mafia don, then your minor antagonists might be your protagonist’s family members or co-workers. They may not even have a direct connection to your protagonist at all, but rather just a vested interest in preventing his goal of bringing the don to justice.

Creating contrast and pertinence in each instance of conflict

Now that you’ve identified a handful of important antagonists, your next step will be answering the following questions:

How will these characters stand between your protagonist and what he wants?

This is always the most important question to ask yourself about any potential opponent. If a character isn’t standing in your protagonist’s way, then he’s not an antagonist.

How will these characters attack your protagonist’s weakness in different ways?

Each of these antagonists needs to oppose your protagonist in a different way. In short, Henchman #1 and Henchman #2, who are only in the story to carry out the bidding of the Evil Mastermind, do not qualify as antagonists in their own right. You’re looking for characters who are going to attack your protagonist from different directions. His fight with the main antagonist will be head-on; the minor antagonists will come at him from the sides.

How do the opponents’ motives and values differ from your protagonist’s—and from each other’s?

Here’s where the whole exercise suddenly gets deep. Your protagonist’s values—and how they evolve over the course of the story—are what create the framework for your story’s theme. If your protagonist is going after that mafia don out of vengeance, but learns to appreciate justice over the course of the story, your theme will probably center around the moral ramifications of revenge.

But a character’s value system can’t exist in a vacuum. What he believes—and how he acts upon those beliefs—only matters insofar as his beliefs are opposed (and thereby tested) by the other characters’ value systems. In the plot, your antagonists’ chief purpose is to prevent your character from reaching his goal. But in the theme, your antagonists serve to challenge your protagonist’s motive for wanting that goal.

On the basic level of one-on-one conflict, you’ll be presenting a relatively black and white perspective of your theme. The protagonist has one idea, and the main antagonist has another. But when you deepen your conflicts, you have the opportunity to also deepen your theme by giving each antagonist a different motive and value system.

Layering your conflicts

Finally, once you’ve identified your story’s antagonists—and once you’ve figured out how and why they will each oppose your protagonist in a different way—you now get to have the fun of taking it one step further. Instead of merely presenting conflict between your protagonist and his antagonists, why not see if you can create a little organic conflict between each of the antagonists as well?

Script doctor John Truby calls this “four-corner opposition.”

In his words, this approach “allows you to create a story of potentially epic scope and yet keep its essential organic unity.” You’ll have created endless possibilities for conflict without endangering the thematic purity of your story’s focus.

*****

K.M. Weiland is the author of the epic fantasy Dreamlander, the historical western A Man Called Outlaw and the medieval epic Behold the Dawn. She enjoys mentoring other authors through her website Helping Writers Become Authors, her books Outlining Your Novel and Structuring Your Novel, and her instructional CD Conquering Writer’s Block and Summoning Inspiration. She makes her home in western Nebraska.

How to Create Layers of Thematically Pertinent Conflict is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

August 21, 2013

Improving Your Fiction: The Relationship Chart – Part 2

Part 2 of 3, from guest blogger Art Holcomb

By now you’ve had some time with the Relationship Chart for your own story and the example I gave from the movie DIE HARD. Hopefully, you’re beginning to see some of the depth to be plumbed by truly understanding our characters.

Before we move on, I want to share with you something to keep in mind while you write. In both Story Physics and Story Engineering, Larry has laid out for you the building blocks of great storytelling. Derived from his work, I want to offer you a universal short hand for describing the true mission of every story.

I got this particular verbiage from screenwriter William Martell and think it’s both elegant and powerful.

He describes a story like this:

A story is when a character is forced to deal with an emotional problem (usually within the character arc) in order to solve an external problem (plot) so as to prevent a catastrophic event from occurring.

Let’s break this down:

The Emotional Problem : The character arc as s/he moves from one state to another

The External Problem: The framework and mechanism for conflict and tension

The Catastrophic Event: The real-life reason to change

The point here is: the larger story (the plot) is there to serve the smaller but more vital story (the character emotional arc). While things may happen in the plotline, meaningful change – the kind that strike home so powerfully with the reader – can only happen within the character arc, which is created by the conflicts within the story’s relationships. Understanding this is what gives you the power to tell great stories.

So – back to the Relationship Chart. Here are a couple of exercises you can do to deepen your understanding:

PAIR ‘EM UP:

Go through and consider each pairing for current and potential relationships. Mark each as they seem to apply. Are they:

Current: Allies, Enemies, Strangers, Lovers?

Potential: Allies, Enemies, Strangers, Lovers?

What do these pairings suggest to you?

MAKE ME FEEL:

Now, let’s consider the effect that one character has on another – for each pairing, describe the emotional effect that each character has on another:

For example, from Box A, you would concisely describe:

How the Hero makes the Villain feel? AND

How the Villain makes the Hero feel?

(Remember, relationships are rarely equal and never identical. Look at each one from each character’s unique perspective. This may take a while, but can be invaluable)

MATCH’EM UP: This one is about the absolutes in your story – the relationships that will not change. Write down:

“Peas in a Pod” – Which characters will ALWAYS get along?

“Oil and Water” – Which ones will NEVER get along?

(It’s easy to see how the “Peas “will always stand together but are there any circumstances that the “Oil & Waters” could ban together –say, against a greater outside threat?)

Compare this to the answer you gave from Part 1 of the series. Do you see the patterns developing? Are you seeing how much more there really is to your characters?

HOMEWORK FOR NEXT TIME:

Take this new understanding of character and test it against that little problem story idea you’ve been noodling with – the one you want to write but could not seem to get a handle on. See if it now begins to reveal itself to you.

I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised.

Next time, we’ll conclude the series with The Bonus Round – where the questions get more difficult but the insight are priceless.

*****

Art Holcomb is a screenwriter and comic book creator. This post is an excerpt from his new writing book, tentatively entitled SAVE YOUR STORY: How to Resurrect Your Abandoned Story and Get It Written NOW!

Improving Your Fiction: The Relationship Chart – Part 2 is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

August 19, 2013

Improving Your Fiction: The Relationship Chart – Part 1

More goodness from guest poster Art Holcomb.

*****

Relationships are at the heart of all great stories.

They bond the reader to the work by giving them someone to root for (or against). They are the foundation of the subplots which broaden and deepen our novels and films. And they supply the emotional reactions that propel the plot forward.

I first created The Relationship Chart to keep tract of the characters at work in my comic book scripts but I soon the discovered that it was a powerful tool for exploring and deepening the characters and forces within any story. When paired with what you’ve learned in THE RULE BOOK series, you will soon see the power you can create in your own writing by knowing who your characters truly are.

Before we begin: If it’s been awhile, please take a moment to review your Rule Book to re-acquaint yourself with the characters we’ll be discussing.

As a guide along the way, I have included a very basic RELATIONSHIP CHART-Die hard – 1a for the main characters in the film DIE HARD (1988, screenplay by Steven E. de Souza and Jeb Stuart). I use this movie as an example here because it is extremely well written and I find that most people are familiar with the plot.

As you complete your own Chart below, feel free to use the DIE HARD for comparison and inspiration.

Now . . . once you’re ready, let’s head straight to…

INSTRUCTIONS:

Attached here is the blank RELATIONSHIP CHART which is very similar to the one used for your own Rule Book.

First off, let’s replace the character types I’ve include with the names from your own story. Make sure that each name appears twice – once across the top and once along the sides. The dark squares in the Chart should correspond with the intersection to two identical names and don’t require any information.

Okay, once that’s done, let’s have some fun…

Part 1 – COMPLETING THE CHART:

FILL IN THE BLANKS: In each box, describe the relationship as best you can as concisely as possible. Follow the examples at the bottom of the Chart. The box will expand to fit whatever description you put there. (Remember, you may not use all the boxes, depending on the length and type of story). Use the DIE HARD chart as an example.

(The point to remember here is that not all relationships are the same, in that how Character A feels about B will not be the same as the way that B feels about A. Perspective is everything.)

LABEL ‘EM: Now, take a look at each relationship separately and then make the appropriate mark in the box:

If the two characters are complementary (alike with common goals), mark it with a (+).

If they are adversarial and have natural conflict, put in an (-)

If neither is true, put an (=).

Part 2 – THE QUESTIONS:On a separate piece of paper or file, answer as many questions as you can:

GOALS: In this exercise, we’ll use the information you wrote down under the LABEL ‘EM section to create the following lists:

Which characters have CONFLICTING goals?

Which ones have COMMON goals?

THE HERO AND ME: The Hero’s Plan is the one that the readers are rooting for. Show here how the two opposing sides might take shape.

Consider each character in relationship to the Hero:

“Is this person an OBSTACLE to OR is a PARTNER in the Hero’s Plan?”

(If neither is true, think twice about whether they’re necessary to the story.)

DIGGING DEEP: Answers these questions as quickly as you can. If the answers aren’t on the tip of your tongue – or finger tips – deeper thought is needed:

What one word describes each character best?

What is the Hero’s flaw? How is it revealed? Is s/he blind to it?

What person/actor is the inspiration for the Hero? Villain? Others?

What does each character care most deeply about?

What is each character’s greatest fear?

What is each character’s motivation? Possibilitiescan be:

Justice,

Revenge,

Connection with others/love/friendship

Home/Place in the World

Meaning or Purpose

Wealth / Security

Power over others / Control

Fame

SUMMARY: That wasn’t too hard, was it? And now you have the basis for understanding the depth of your characters and the possibilities of their relationships. Understanding exactly how each one relates to the other will make writing for them so much easier, and new possibilities for conflict, plot twists, and description will come to light with every review of the chart.

NEXT TIME: We’ll go even deeper into the heart of these characters and explore how this understanding can breathe new life into your story.

*****

Art Holcomb is a screenwriter and comic book creator. This post is an excerpt from his new writing book, tentatively entitled SAVE YOUR STORY: How to Resurrect Your Abandoned Story and Get It Written NOW!

Improving Your Fiction: The Relationship Chart – Part 1 is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

August 10, 2013

The Rule Book — by Art Holcomb, Part 2

Part 2 of 2

Okay, you’ve had some time with the Rule Book Relationship Chart …

Remember: you can substitute your characters’ names for the character type across the top, and the change the emotions listed along the side as well.

Once you’re finished making the initially pass, we can start having fun!

#1: Look at any missing boxes. Are these emotions that your character should have or are they not important to the story? Try putting yourself in the character’s shoes – based on what you know of them already, how would these emotions make them react? If you used someone you already know as an inspiration for the character, imagine them is a similar situation. Remember, the more you know about the character, the better they will respond to what you want them to do.

#2: Now, highlight the characters that have similar emotional reactions. Do you have characters that overreact when angry or shame-filled? Or ones that recede into the woodwork when feeling shy? These characters might share qualities that make them potential allies – they have something in common and this might be useful in upcoming scenes. However, while it might be interesting to have two similar people reacting the same way in the same situation at the same time, it might not make for good drama. Play with it for a while before you commit to it.

#3: Now look at those characters that have emotional responses that are completely different.

This can play out in a couple of ways:

a: The characters could be complementary, such as one that needs to be cared for when hurt or frightened and another who is happiest when caring for others. This creates a natural bond – and may be something you hadn’t realized before. They can make for strong allies.

b: However, characters can also clash and be naturally adversarial if their emotional responses do not complement, such as when one is deeply embarrassed when confronted and another is abusive when angry. This creates organic conflict on an emotional level and has the potential for exciting drama.

#4: So, ask yourself:

What makes this character relatable? What will the reader find endearing, interesting and/or vulnerable about this character based of their emotional response? This is vital because your ability to attract an audience depends upon making this connection, especially with the major characters.

Based on your chart, which characters are driven to move forward but are emotional held back by something? This illustrates their basic humanity and builds that reader-protagonist connection.

In what ways do the emotions of any individual character seem to contradict each other? That is to say, in what ways are your characters broken? We like our characters, especially the Heroes and Villains to be a bit like broken toys, walking/talking puzzles with a couple of pieces missing.

So, in what way are they strong yet helpless? Happy yet have real shame issues? Frightened yet courageous? This is the real nature of a human being – a collection of contradictions that fight for control in our lives. Through this, the reader will be able to see something of themselves in the characters. Seeing those missing pieces put into place makes for satisfying storytelling. And it’ s what makes a dedicated fan out of a casual reader.

#5: At the heart of every character-oriented story is the emotional arc of the hero – that profound change that makes all the conflict and turmoil of Acts 2 and 3 worthwhile. And this chart shows you the way to create that. If, say, your hero’s main emotional stumbling block is that he can’t get past his anger, then the change is:

From Angry -> Acceptance

… and each trial that he faces from the First Plot Point through to the Climax peels away at that anger – layer by layer – like the leaves on an artichoke to reveal the true nature that lies at the heart of every character. (Keep in mind that we’re looking for an artichoke here and not an onion: a weak character is one that has nothing deeper than anger to sustain them and it just doesn’t work.)

Similar arcs for the other emotions we’ve talked about would be:

From Hurt -> Healed

From Frightened -> Secure

From Embarrassed -> Self-possessed

From Shy -> Courageous

From Helpless -> Capable

From Guilty -> Vindicated

From Shameful -> Virtuous

From Sad -> Joyful

Play with this awhile and you’ll see how it can deepen your understanding of your characters. The more you know about how they can react, the most fully you can write them.

The Next Step: The next task in the process of understanding characters is to chart out the way each character relates to one other, highlighting and developing the potential conflicts and contradictions we’ve discussed here; there’s a chart I use for this as well.

If interested, I can do a post on that– just drop me a comment here if interested.

These, then, are the tools we can use to build the conflicts throughout the story for both our plotline and our emotional arcs.

Remember: creating three dimensional characters in your story gives the reader someone to identify with and root for. It creates that vital, emotional bond between the writer and reader.

And it makes your writing a deeper and more authentic expression of who you really are!

So . . . until next time, keep writing ==

Art

****

If you missed Part 1, read it HERE.

Art Holcomb is a screenwriter and comic book creator. This post is taken from his new writing book, tentatively entitled SAVE YOUR STORY: How to Resurrect Your Abandoned Story and Get It Written NOW!

He is also a frequent contributor here at Storyfix.com. Use the Search bar to the right to find more Art Holcomb gold.

The Rule Book — by Art Holcomb, Part 2 is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

August 7, 2013

The Rule Book — by Art Holcomb, Part 1

(Quick aside… a few days ago you received a post from me entitled, “Are You the One out of Ten?” It may have looked familiar… and it should have — it was originally posted on June 24th. Thing is, I didn’t send it. I haven’t opened up my WordPress dashboard since well over a week ago. Some undefined WP gremlin did something undefined that ended up redistributing the post. I’ve asked all the WP geniuses I know, and nobody can explain it… which means, they secretly believe it was me after all. Twasn’t. Theories welcomed. Sorry to clutter your inbox in this instance.)

The Rule Book — A Guest Post from Art Holcomb

Part 1 of 2

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about motives and consequences.

If there are two separate story paths that exist in each tale we tell, then there is an engine that drives each and they are quite different from one another:

The Plot line moves forward when we ask the question: “What happens next?’

The Emotional line develops when we ask, in contrast: “How will my characters react to the next turn-of – events?”

Every story begins at the same place. Act I always starts with a status quo – life as normal – until the Inciting Incident occurs. Then suddenly, something changes and our characters begin their journey by reacting to it. Nothing happens without the Incident and the subsequent and necessary Reaction.

The model is always:

Action –>Emotion –> Reaction –>Emotion -> Action

For example, in the movie Casablanca, Rick is happy running his little café “not sticking his neck out for anyone” (Act I status quo) until his old flame Ilsa arrives with the guy she dumped Rick for (Inciting Incident). Rick’s old wounds are ripped open (emotion) and he must eventually decide what to do about Ilsa, the letters of transit, and of course, those ever-present Nazis (reaction/consequence).

So . . . The Incident starts the ball rolling. We have an emotional reaction to this event which produces a physical action, which in term elicits its own emotional response elsewhere and the requisite action that follows.

In this way, emotions are the motive for what we do and consequences are the results of acting upon those motives.

If we’re honest with ourselves, we all have our own hot buttons issue to which we react in predictable ways. It’s only human nature. For example, some people get sad when they receive a rejection to a submission, while others double down emotionally and get back to work. Conversely, some people are elated and celebrate when they get a piece accepted for publication, while others become worried that they won’t find a supportive audience. And still others might simply acknowledge the fact and get to work on the next piece.

But, somewhere in the cobwebbed covered vault we call the human psyche, there is a rule book inside all of us.

If you doubt it, ask your spouse, partner or your parents the following question.

Go ahead – I dare you. Ask them:

“When I am ______ (sad, angry, frightened, or threatened), what do I usually do?”

However, be prepared to be surprised. We, as people, hardly ever see ourselves as others see us. Your parents or partners’ answers may surprise you.

In the end, we’re all predictably different . . . and so must our characters be.

You should never be surprised by the way your characters act in your stories. Each character is unconsciously designed by you to react in a specific and predictable way. This is natural and necessary because the emotional change we seek in our protagonist at the end of the story – the very thing that makes the character-driven story so powerful and relatable – occurs at the very moment that s/he breaks out of their old pattern, and creates a new rule - and identity – for themselves.

Storytelling masters like Michael Hauge and Christopher Vogler (both of whom blurbed Larry’s first writing book, “Story Engineering“) talk about this rule change being a return to the very essence of who a character really is, a kind of stripping away of the emotional protective layer that Life forces us all to create as we grow. This change is what brings our hero one step closer to self-realization and his true nature.

So . . . let us turn this vague concept into something concrete and useful.

Let’s take a look at the rules you have given to your characters in your current work.

Here is a downloadable blank MS-Word Chart that shows the various possible character archetypes in your story along the top and the emotions that they are likely to go through in the course of the story listed along the left side. Both the names and emotions can be easily changed to fit your current tale. In the appropriate box, write the rule that this character will follow when confronted with this emotion. For example in the first box would go the answer to, “How does the HERO react when s/he is HURT?” The boxes will expand to fit whatever notes you want to include.

Complete as many boxes as you can. Empty boxes may indicate that more thought may be needed to enhance your understanding of the character.

Beware: You may think that there are nuances and subtleties in the way a character would react to, say, being hurt, depending on the cause; but if you look deeper you will find the controlling reaction should always be the same – until growth takes place and that particular rule changes.

Once completed, you will have a snapshot of the emotional range of your story.

This is your canvas.

This is where you will deepen your story.

Use as many colors and techniques as you can.

These emotions, taken as a mosaic of the character’s psyche, supply dimension and depth to the narrative, leading us to understand who that character is, why s/he must change and what they have the chance of becoming.

By completing your own Rule Book chart, you will be able to see the similarities and differences in your characters; some of these differences will suggest plot points, twists and turns you can use that you might not have seen before.

And by understanding the emotional rules of your main characters, you’ll be able to create the most powerful and dramatic emotional journey for your hero.

And isn’t that what we all came to see?

Part 2 of the Rule Book will be along in a couple of days, when we’ll talk about the wealth of story possibilities this process creates.

Until next time, keep writing!

Art

*****

To read Part 2 of this post, click HERE.

Art Holcomb is a screenwriter and comic book creator. This post is taken from his new writing book, tentatively entitled SAVE YOUR STORY: How to Resurrect Your Abandoned Story and Get It Written NOW!

The Rule Book — by Art Holcomb, Part 1 is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The Rule Book

(Quick aside… a few days ago you received a post from me entitled, “Are You the One out of Ten?” It may have looked familiar… and it should have — it was originally posted on June 24th. Thing is, I didn’t send it. I haven’t opened up my WordPress dashboard since well over a week ago. Some undefined WP gremlin did something undefined that ended up redistributing the post. I’ve asked all the WP geniuses I know, and nobody can explain it… which means, they secretly believe it was me after all. Twasn’t. Theories welcomed. Sorry to clutter your inbox in this instance.)

The Rule Book — A Guest Post from Art Holcomb

Part 1 of 2

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about motives and consequences.

If there are two separate story paths that exist in each tale we tell, then there is an engine that drives each and they are quite different from one another:

The Plot line moves forward when we ask the question: “What happens next?’

The Emotional line develops when we ask, in contrast: “How will my characters react to the next turn-of – events?”

Every story begins at the same place. Act I always starts with a status quo – life as normal – until the Inciting Incident occurs. Then suddenly, something changes and our characters begin their journey by reacting to it. Nothing happens without the Incident and the subsequent and necessary Reaction.

The model is always:

Action –>Emotion –> Reaction –>Emotion -> Action

For example, in the movie Casablanca, Rick is happy running his little café “not sticking his neck out for anyone” (Act I status quo) until his old flame Ilsa arrives with the guy she dumped Rick for (Inciting Incident). Rick’s old wounds are ripped open (emotion) and he must eventually decide what to do about Ilsa, the letters of transit, and of course, those ever-present Nazis (reaction/consequence).

So . . . The Incident starts the ball rolling. We have an emotional reaction to this event which produces a physical action, which in term elicits its own emotional response elsewhere and the requisite action that follows.

In this way, emotions are the motive for what we do and consequences are the results of acting upon those motives.

If we’re honest with ourselves, we all have our own hot buttons issue to which we react in predictable ways. It’s only human nature. For example, some people get sad when they receive a rejection to a submission, while others double down emotionally and get back to work. Conversely, some people are elated and celebrate when they get a piece accepted for publication, while others become worried that they won’t find a supportive audience. And still others might simply acknowledge the fact and get to work on the next piece.

But, somewhere in the cobwebbed covered vault we call the human psyche, there is a rule book inside all of us.

If you doubt it, ask your spouse, partner or your parents the following question.

Go ahead – I dare you. Ask them:

“When I am ______ (sad, angry, frightened, or threatened), what do I usually do?”

However, be prepared to be surprised. We, as people, hardly ever see ourselves as others see us. Your parents or partners’ answers may surprise you.

In the end, we’re all predictably different . . . and so must our characters be.

You should never be surprised by the way your characters act in your stories. Each character is unconsciously designed by you to react in a specific and predictable way. This is natural and necessary because the emotional change we seek in our protagonist at the end of the story – the very thing that makes the character-driven story so powerful and relatable – occurs at the very moment that s/he breaks out of their old pattern, and creates a new rule - and identity – for themselves.

Storytelling masters like Michael Hauge and Christopher Vogler (both of whom blurbed Larry’s first writing book, “Story Engineering“) talk about this rule change being a return to the very essence of who a character really is, a kind of stripping away of the emotional protective layer that Life forces us all to create as we grow. This change is what brings our hero one step closer to self-realization and his true nature.

So . . . let us turn this vague concept into something concrete and useful.

Let’s take a look at the rules you have given to your characters in your current work.

Here is a downloadable blank MS-Word Chart that shows the various possible character archetypes in your story along the top and the emotions that they are likely to go through in the course of the story listed along the left side. Both the names and emotions can be easily changed to fit your current tale. In the appropriate box, write the rule that this character will follow when confronted with this emotion. For example in the first box would go the answer to, “How does the HERO react when s/he is HURT?” The boxes will expand to fit whatever notes you want to include.

Complete as many boxes as you can. Empty boxes may indicate that more thought may be needed to enhance your understanding of the character.

Beware: You may think that there are nuances and subtleties in the way a character would react to, say, being hurt, depending on the cause; but if you look deeper you will find the controlling reaction should always be the same – until growth takes place and that particular rule changes.

Once completed, you will have a snapshot of the emotional range of your story.

This is your canvas.

This is where you will deepen your story.

Use as many colors and techniques as you can.

These emotions, taken as a mosaic of the character’s psyche, supply dimension and depth to the narrative, leading us to understand who that character is, why s/he must change and what they have the chance of becoming.

By completing your own Rule Book chart, you will be able to see the similarities and differences in your characters; some of these differences will suggest plot points, twists and turns you can use that you might not have seen before.

And by understanding the emotional rules of your main characters, you’ll be able to create the most powerful and dramatic emotional journey for your hero.

And isn’t that what we all came to see?

Part 2 of the Rule Book will be along in a couple of days, when we’ll talk about the wealth of story possibilities this process creates.

Until next time, keep writing!

Art

*****

Art Holcomb is a screenwriter and comic book creator. This post is taken from his new writing book, tentatively entitled SAVE YOUR STORY: How to Resurrect Your Abandoned Story and Get It Written NOW!

The Rule Book is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

August 1, 2013

Message to My Email-Feed Readers

My posts go out in one of two ways — as an immediate Feed, or the next morning via email. Which means you often don’t click on to the site itself. That works… relative to yesterday’s post, it didn’t.

When I received the post via email this morning (yes, I subscribe to my own blog… wouldn’t you?), I quickly noticed the most important – and fun – part wasn’t there. Not even a gobbled remnant of the code, which sometimes happens… it was skipped altogether.

That’s like someone stealing the steak that left the kitchen on a sizzling platter… the main course never made it to the table.

So here it is… a hilarious video summarizing The Hero’s Journey, with Jerseyesque narration worthy of Andrew Dice Clay. It’s surprisingly informative and cleverly written and performed. The link will take you to the post on the site, where the video (halfway down) awaits. Worth the five minutes it takes.

Also, as an epilogue… you’ll notice the title refers to Saturday morning… that’s a reference to the fact that the video uses puppets, and thus, a connection to Saturday morning television. But not everyone gets even simple social glibness like this.

Then I got an email yesterday, from someone saying this: “I just received your latest post entitled Saturday Morning Version of The Hero’s Journey. But it’s WEDNESDAY. Get your shit together, dude.”

You can swim with the sharks, or drown with the idiots.

Thanks for reading my stuff.

Message to My Email-Feed Readers is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

July 31, 2013

Saturday Morning Version of “The Hero’s Journey”

Two words: hand sock. You’ll see.

Really, we need to take storytelling more seriously than this… which in an ironic twist means, this IS serious. Even when it’s hilariously rendered.

It’s also potentially confusing as hell. Which is why I write about it using what I believe to be more accessible, clearer terminology and modeling. It’s the same stuff. And why I’ve added some clarifications of my own at the end of this post.

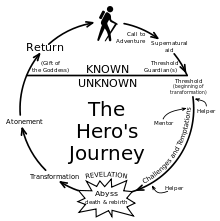

You’ve heard of The Hero’s Journey.

Chances are you’ve studied it. Joseph Campbell gets credit for it (calls it a Monomyth, a term borrowed from James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake), as presented in his book, The Hero With A Thousand Faces (1949… it didn’t hit the bestseller list until 1988 — there’s always hope — when PBS aired a special entitled The Power of Myth).

This is how it’s done, no matter how you label the parts. Notice that it’s flexible, something you can spin to your own needs (ie., some of the players in this story model can be embodied by a single character, serving different catalytic purposes).

The more we see it from different angles, the deeper it sinks in.

Thanks to Storyfix friend and frequent contributor Art Holcomb for this one. Watch, laugh and learn.

Here’s what The Hero’s Journey looks like as a graphic (from Wikipedia). The story begins at the top (12:00 noon position), progressing clockwise… literally.

A Few Thoughts on This

This model is not infallible or absolute, it is like most principles, general in nature. For example, the video says that the HERO is just an Average Joe. Not always true. That’s limiting, and you can come up with a library full of exception.

The HERALD has a role, and this mission trumps it actually being a character… it can come into the story in non-character ways. Because… the HERALD is the FIRST PLOT POINT. That mission IS a firm principle… how it enters the story is your call.

The MENTOR character… great idea. Hard to pull off, though, when your hero is a lone wolf. Don’t force this into the story because Joseph Campbell says to.

THRESHOLD GUARDIANS… are some combination of the villain and the villain’s henchmen, and/or any other form of antagonistic force. These often star in your Pinch Points.

SHAPE SHIFTER… when any character either reveals a hidden truth about themselves, including your villain. Useful as a mean of delivering a Plot Point or, more often, the Mid-Point, which is a great place for this.

SHADOW… that’s easy, that’s your main antagonist. The bad guy. The villain. The term applies when that character’s true nature and agenda has been veiled through the course of the story, only to be revealed when it matters. Which is often at the Second Plot Point.

As food for thought goes, you now have a virtual banquet of flavors and courses in front of you. Bon appetite!

*****

The video shown here is from the great Glove and Boots Puppet Blog (I know I know, sounds… kinky… it’s not that), which posts most of its content on Youtube.

As you might have guessed, the guy in the framed picture on the wall behind the puppets in this video is Joseph Campbell.

Saturday Morning Version of “The Hero’s Journey” is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

July 29, 2013

When Words Get In Your Way

Okay, that title is my way of creating some sort of linkage between the brand/mission of this website and the content of this particular post. I get about three emails a day from SEO guys telling me I suck, so this is for them.

Then again, the post itself is really for you. We’re word people, right?

This one cracked me up, and I wanted to share the love. Not sure where it originated – it landed in my inbox with encouragement to forward if I wanted to avoid something horrible showing up in my life – but it is worth sharing. A good laugh always is.

Then again, it does demonstrate the power of the words we choose, and the way in which context controls everything.

And that, when from the mouths of babes, word selection sets the humor bar very high.

Enjoy. I’m off to Portland to teach three workshops at the Willamette Writers Conference. Tough crowd, wish me luck.

****

How Asparagus Got Its Name

A first grade child was asked to write a book report on the entire Bible. Here is what he wrote:

The Children’s Bible in a Nutshell

In the beginning, which occurred near the start, there was nothing but God, darkness, and some gas. The Bible says, “The Lord thy God is one,” but I think He must be a lot older than that.

Anyway, God said, “Give me a light!” and someone did.

Then God made the world.

He split the Adam and made Eve. Adam and Eve were naked, but they weren’t embarrassed because mirrors hadn’t been invented yet.

Adam and Eve disobeyed God by eating one bad apple, so they were driven from the Garden of Eden… not sure what they were driven in though, because they didn’t have cars.

Adam and Eve had a son, Cain, who hated his brother as long as he was Abel. Pretty soon all of the early people died off, except for Methuselah, who lived to be like a million or something.

One of the next important people was Noah, who was a good guy, but one of his kids was kind of a Ham. Noah built a large boat and put his family and some animals on it. He asked some other people to join him, but they said they would have to take a rain check.

After Noah came Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Jacob was more famous than his brother, Esau, because Esau sold Jacob his birthmark in exchange for some pot roast. Jacob had a son named Joseph who wore a really loud sports coat.

Another important Bible guy is Moses, whose real name was Charlton Heston. Moses led the Israel Lights out of Egypt and away from the evil Pharaoh after God sent ten plagues on Pharaoh’s people. These plagues included frogs, mice, lice, bowels, and no cable.

God fed the Israel Lights every day with manicotti. Then he gave them His Top Ten Commandments. These include: don’t lie, cheat, smoke, dance, or covet your neighbor’s stuff.

Oh, yeah, I just thought of one more: Humor thy father and thy mother.

One of Moses’ best helpers was Joshua who was the first Bible guy to use spies. Joshua fought the battle of Genital and the fence fell over on the town.

After Joshua came David. He got to be king by killing a giant with a slingshot. He had a son named Solomon who had about 300 wives and 500 porcupines. My teacher says he was wise, but that doesn’t sound very wise to me.

After Solomon there were a bunch of major league prophets. One of these was Jonah, who was swallowed by a big whale and then barfed up on the shore.

There were also some minor league prophets, but I guess we don’t have to worry about them.

After the Old Testament came the New Testament. Jesus is the star of The New Testament. He was born in Bethlehem in a barn. (I wish I had been born in a barn too, because my Mom is always saying to me, “Close the door! Were you born in a barn?” It would be nice to say, ”As a matter of fact, I was.”)

During His life, Jesus had many arguments with sinners like the Pharisees and the Republicans. Jesus also had twelve opossums. The worst one was Judas Asparagus. Judas was so evil that they named a terrible vegetable after him.

Jesus was a great man. He healed many leopards and even preached to some Germans on the Mount. But the Democrats and all those guys put Jesus on trial before Pontius the Pilot. Pilot didn’t stick up for Jesus. He just washed his hands instead.

Anyways, Jesus died for our sins, then came back to life again. He went up to Heaven but will be back at the end of the Aluminum. His return is foretold in the book of Revolution.

When Words Get In Your Way is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com