Lily Salter's Blog, page 239

November 15, 2017

Steven Mnuchin and wife Louise Linton pose with sheets of cash, get destroyed on Twitter

Louise Linton and Steven Mnuchin hold up a sheet of new $1 bills. (Credit: AP/Jacquelyn Martin)

As the GOP tax reform plan has been thrown into question, Washington D.C.’s most popular duo posed for pictures with freshly printed sheets of cold, hard cash.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and his wife, Louise Linton, looked ecstatic to hold up the sheets of $1 bills on Wednesday at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, D.C. The individual bills are the first to feature Mnuchin’s signature, as well as U.S. Treasurer Jovita Carranza, which are expected to begin circulating in December, CNN reported.

Naturally, the pictures immediately put Twitter users to work and hilarious memes and caption contests eventually ensued, and they did not disappoint.

“Find someone who looks at you the way Louise Linton looks at Steve Mnuchin holding a sheet of dollar bills with his name on them,” one user tweeted.

Find someone who looks at you the way Louise Linton looks at Steve Mnuchin holding a sheet of dollar bills with his name on them pic.twitter.com/3fGXmJti6c

— Christopher Ingraham (@_cingraham) November 15, 2017

“Louise Linton holds the great love of her life. Also pictured, her husband #StevenMnuchin,” Renee Graham, of the Boston Globe tweeted.

Louise Linton holds the great love of her life. Also pictured, her husband #StevenMnuchin. https://t.co/IFHTGrkjwq — Renee Graham (@reneeygraham) November 15, 2017

you cannot parody these folks pic.twitter.com/PfDXB0qXTp

— southpaw (@nycsouthpaw) November 15, 2017

“Just a friendly reminder that the GOP wants to raise taxes on the middle class & take health insurance away from millions of Americans so people like Louise Linton and Steve Mnuchin can get a tax cut,” another user wrote.

Just a friendly reminder that the GOP wants to raise taxes on the middle class & take health insurance away from millions of Americans so people like Louise Linton and Steve Mnuchin can get a tax cut. pic.twitter.com/TbBG2dcWsx — Caroline O. (@RVAwonk) November 15, 2017

“Why do Louise Linton and Steve Mnuchin look like they’re on the way to close down an orphanage?” a user tweeted.

Why do Louise Linton and Steve Mnuchin look like they’re on the way to close down an orphanage? pic.twitter.com/s3zyAHQhch

— Mike Beauvais, Based on the Novel Push by Sapphire (@MikeBeauvais) November 15, 2017

The couple had become the center of controversy in late August after Linton posted a picture to her Instagram account of her and Mnuchin getting out of a government plane. She included several clothing designers in her post and also argued with a commenter and bragged about her wealth, which she later apologized for.

“Great #daytrip to #Kentucky!” she wrote, and added the hashtags, “#nicest, #people, #countryside, #rolandmouret, #hermesscarf, #tomford, #valentino, #usa.”

Many had believed the two had gone to Kentucky to view the total solar eclipse, but Mnuchin denied that and insisted he wasn’t interested in viewing the eclipse because he’s from New York.

“People in Kentucky took this stuff very seriously. Being a New Yorker, I don’t have any interest in watching the eclipse,” Mnuchin said.

The perspective on homeschooling

(Credit: Getty/Steve Debenport)

Homeschooling has had a pretty consistent reputation over the years. The entertainment world has sold us on a picture of macrame and totalistic ideologies. For example, the opening sequence to the film Mean Girls would have you believe there are few paths that end in homeschooling, and decidedly all lead to the socially awkward.

Homeschooling has had a pretty consistent reputation over the years. The entertainment world has sold us on a picture of macrame and totalistic ideologies. For example, the opening sequence to the film Mean Girls would have you believe there are few paths that end in homeschooling, and decidedly all lead to the socially awkward.

Alternatively, let’s consider the school system. With serious underfunding issues and skyrocketing class sizes; a system where passionate teachers are practically being muscled out, It’s no wonder homeschooling has increased by a staggering 61% in just a decade. Parents are unlocking a new world of education. Could there be something to this homeschooling thing after all?

The following are three disadvantages and three advantages of homeschooling.

Home truth (the cons)

The ultimate echochamber

According to a government report released this year, only a quarter of parents take any prep before homeschooling their children. The legislation on homeschooling differs so dramatically from state to state, and case to case making it extremely difficult for any sense of community between peers. A homeschooling environment not only deprives a child of a holistic education, but breeds an environment for potential abuse of power. In contrast, a school is a place where a child’s views are challenged by different personalities, points of views and ways of life. They also have access to nurses and counselors. When a child attends a traditional school they are exposed to socialisation. This is as imperative in early childhood as it is in adolescence, and the effects carry through to adulthood.

Financial burden

For many families the question of education is limited to most accessible and most affordable. For homeschooling to work, at least one parent is typically playing an active role in the education process. This means planning and execution. At the very most a tutor can be brought in, meaning adding a salary. Ultimately, Homeschooling means giving up an income. Homeschooling does not come with scholarships or donors. With nearly half the families in the US live 250% below the poverty line, is homeschooling just another privilege keeping the educated, educated, and the working class, struggling?

Homeschooling sets unnecessary hurdles

The GED, or high school equivalency are tests that demonstrate that the level of knowledge obtained by a student is that of a high school graduate. GED is the most common standardized test for a homeschooler. And although it is easily accessible, The GED barely gets you through the first hoop to employment. Jobs requiring a GED alone will keep your child at minimum wage with little room for growth. Colleges and employers, not only value accredited diplomas, but also extracurriculars. Students who have participated in internships have a hiring advantage of 75% and a higher salary on average by 31%. Navigating the job market is a daunting task at the best of times. Isn’t every parent’s mission to prepare their children for the great big world?

There’s no place like home (the pros)

Active members of the community

Homeschooling as an education practice builds itself on the values of family, community and involvement. Homeschooling methods, are highly adaptable and grow as their surroundings do. Homeschooled children are rarely in one on one situations, rather participating as active members of their community. Every day is a possible field trip, a lesson to learn, no matter the size of the community. A rural student, and an urban student both have the advantage of seeing the consequences of their actions as the world around them changes.

Fostering academic curiosity through role-modeling

By taking on homeschooling you are role-modeling for your child the ideals of personal responsibility and a strong sense of identity. Children develop a sense of agency about their learning, and its trajectory, when they feel their role in it. Homeschooled kids are hardly limited on options. 74% of homeschoolers go on to tertiary education, with a college graduation rate of 66.7% over traditional schools rate of 57.5%. Education could be about seizing opportunity. The school culture breeds an atmosphere of competitive achievement. Kids become focused on ‘winning’ rather than learning. Knowledge is not something to be memorized, but rather to be discovered.

A sound investment

With homeschooling the output matches the input, no matter the family situation. Your child’s education is in your hands and within your resources. Research shows that family income has little to no influence on their ability to successfully homeschool. Public schools, on the other hand, receive funding according to district. This means students education is staggered depending on their financial situation. Consider the reality of public school: The extracurricular activities after an 8 hour day inside, tutors – to help keep your child’s head above water in a competitive environment, and whatever laptop and accessory the school deems mandatory. With public schools choking under shrinking budget and often misappropriated funds, it’s hard to face copping the hidden costs of public education.

Bottom line:

What worked once may not be working any longer. Homeschooling takes a great deal of commitment, personally and legislatively. Are we moving towards a future of educational pioneers or should we leave the educating to the classroom?

How to wield influence and sell weaponry in Washington

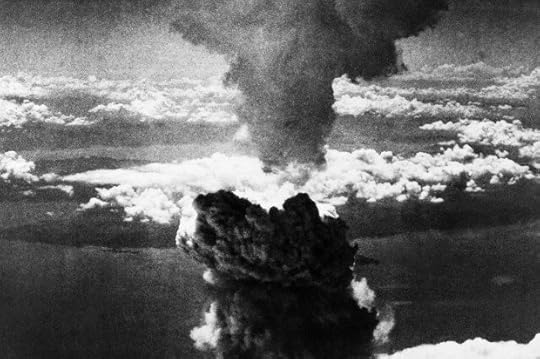

FILE - In this Aug. 9, 1945 file photo, a mushroom cloud rises moments after the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, southern Japan. On two days in August 1945, U.S. planes dropped two atomic bombs, one on Hiroshima, one on Nagasaki, the first and only time nuclear weapons have been used. Their destructive power was unprecedented, incinerating buildings and people, and leaving lifelong scars on survivors, not just physical but also psychological, and on the cities themselves. Days later, World War II was over. (AP Photo/File) (Credit: AP)

[This piece has been updated and adapted from William D. Hartung’s “Nuclear Politics” in Sleepwalking to Armageddon: The Threat of Nuclear Annihilation, edited by Helen Caldicott and just published by the New Press.]

Until recently, few of us woke up worrying about the threat of nuclear war. Such dangers seemed like Cold War relics, associated with outmoded practices like building fallout shelters and “duck and cover” drills.

But give Donald Trump credit. When it comes to nukes, he’s gotten our attention. He’s prompted renewed concern, if not outright alarm, about the possibility that such weaponry could actually be used for the first time since the 6th and 9th of August 1945. That’s what happens when the man in the Oval Office begins threatening to rain “fire and fury like the world has never seen” on another country or, as he did in his presidential campaign, claimingcryptically that, when it comes to nuclear weapons, “the devastation is very important to me.”

Trump’s pronouncements are at least as unnerving as President Ronald Reagan’s infamous “joke” that “we begin bombing [the Soviet Union] in five minutes” or the comment of a Reagan aide that, “with enough shovels,” the United States could survive a superpower nuclear exchange.

Whether in the 1980s or today, a tough-guy attitude on nuclear weapons, when combined with an apparent ignorance about their world-ending potential, adds up to a toxic brew. An unprecedented global anti-nuclear movement — spearheaded by the European Nuclear Disarmament campaign and, in the United States, the Nuclear Freeze campaign — helped turn President Reagan around, so much so that he later agreed to substantial nuclear cuts and acknowledged that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

It remains to be seen whether anything could similarly influence Donald Trump. One thing is certain, however: the president has plenty of nuclear weapons to back up his aggressive rhetoric — more than 4,000 of them in the active U.S. stockpile, when a mere handful of them could obliterate North Korea at the cost of millions of lives. Indeed, a few hundred nuclear warheads could do the same for even the largest of nations and those 4,000, if ever used, could essentially destroy the planet.

In other words, in every sense of the term, the U.S. nuclear arsenal already represents overkill on an almost unimaginable scale. Independent experts from U.S. war colleges suggest that about 300 warheads would be more than enough to deter any country from launching a nuclear attack on the United States.

Despite this, Donald Trump is all in (and more) on the Pentagon’s plan — developed under Barack Obama — to build a new generation of nuclear-armed bombers, submarines, and missiles, as well as new generations of warheads to go with them. The cost of this “modernization” program? The Congressional Budget Office recently pegged it at $1.7 trillion over the next three decades, adjusted for inflation. As Derek Johnson, director of the antinuclear organization Global Zero, has noted, “That’s money we don’t have for an arsenal we don’t need.”

Building a Nuclear Complex

Why the desire for so many nukes? There is, in fact, a dirty little secret behind the massive U.S. arsenal: it has more to do with the power and profits of this country’s major weapons makers than it does with any imaginable strategic considerations.

It may not surprise you to learn that there’s nothing new about the influence the nuclear weapons lobby has over Pentagon spending priorities. The successful machinations of the makers of strategic bombers and intercontinental ballistic missiles, intended to keep taxpayer dollars flowing their way, date back to the dawn of the nuclear age and are the primary reason President Dwight D. Eisenhower coined the term “military-industrial complex” and warned of its dangers in his 1961 farewell address.

Without the development of such weapons, that complex simply would not exist in the form it does today. The Manhattan Project, the vast scientific-industrial endeavor that produced the first such weaponry during World War II, was one of the largest government-funded research and manufacturing projects in history. Today’s nuclear warhead complex is still largely built around facilities and locations that date back to that time.

The Manhattan Project was the first building block of the permanent arms establishment that came to rule Washington. In addition, the nuclear arms race against that other superpower of the era, the Soviet Union, was crucial to the rationale for a permanent war state. In those years, it was the key to sustaining the building, funding, and institutionalizing of the arms establishment.

As Eisenhower noted in that farewell address of his, “a permanent arms industry of vast proportions” had developed for a simple enough reason. In a nuclear age, America had to be ready ahead of time. As he put it, “We can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense.” And that was for a simple enough reason: in an era of potential nuclear war, any society could be destroyed in a matter of hours. There would be no time, as in the past, to mobilize or prepare after the fact.

In addition, there were some very specific ways in which the quest for more nuclear weapons and delivery vehicles drove Eisenhower to give that farewell address. One of his biggest fights was over whether to build a new nuclear bomber. The Air Force and the arms industry were desperate to do so. Eisenhower thought it a waste of money, given all the other nuclear delivery vehicles the U.S. was building at the time. He even cancelled the bomber, only to find himself forced to revive it under immense pressure from the arms lobby. In the process, he lost the larger struggle to rein in the nation’s nuclear buildup and corral the burgeoning military-industrial complex.

At the same time, there were rumblings in the intelligence community, the military establishment, the media, and Congress about a “missile gap” with the Soviet Union. The notion was that Moscow had somehow jumped ahead of the United States in developing and building intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). There was no definitive intelligence to substantiate the claim (and it was later proved to be false). However, a wave of worst-case scenarios leaked by or promoted by intelligence analysts and eagerly backed by industry propaganda made that missile gap part of the everyday news of the time.

Such fears were then exaggerated further, thanks to hawkish journalists of the era like Joseph Alsop and prominent Democratic senators like John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, as well as Stuart Symington, who just happened to be a friend and former colleague of an executive at the aircraft manufacturing company Convair, which, in turn, just happened to make ICBMs. As a result, he lobbied hard on behalf of a Pentagon plan to build more of that corporation’s Atlas ballistic missiles, while Kennedy would famously make the nonexistent missile gap a central theme of his successful 1960 campaign for the presidency.

Eisenhower couldn’t have been more clear-eyed about all of this. He saw the missile gap for the fiction it was or, as he put it, a “useful piece of political demagoguery” for his opponents. “Munitions makers,” he insisted, “are making tremendous efforts towards getting more contracts and in fact seem to be exerting undue influence over the Senators.”

Once Kennedy took office, it became all too apparent that there was no missile gap, but by then it hardly mattered. The damage had been done. Billions of dollars more were flowing into the nuclear-industrial complex to build up an American arsenal of ICBMs already unmatched on the planet.

The techniques that the arms lobby and its allies in government used more than half a century ago to promote sky-high nuclear weapons spending continue to be wielded to this day. The twenty-first-century arms complex employs tools of influence that Kennedy and his compatriots would have found familiar indeed — including millions of dollars in campaign contributions that flow to members of Congress and the continual employment of 700 to 1,000 lobbyists to influence them. At certain moments, in other words, there have been nearly two arms lobbyists for every member of Congress. Much of this sort of activity remains focused on ensuring that nuclear weapons of all types are amply financed and that the funding for the new generations of the bombers, submarines, and missiles that will deliver them stays on track.

When traditional lobbying methods don’t get the job done, the industry’s argument of last resort is jobs — in particular, jobs in the states and districts of key members of Congress. This process is aided by the fact that nuclear weapons facilities are spread remarkably widely across the country. There are nuclear weapons labs in California and New Mexico; a nuclear weapons testing and research site in Nevada; a nuclear warhead assembly and disassembly plant in Texas; a factory in Kansas City, Missouri, that builds nonnuclear parts for such weapons; and a plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, that enriches uranium for those same weapons. There are factories or bases for ICBMs, bombers, and ballistic missile submarines in Connecticut, Georgia, Washington State, California, Ohio, Massachusetts, Louisiana, North Dakota, and Wyoming. Such a nuclear geography ensures that a striking number of congressional representatives will automatically favor more spending on nuclear weapons.

In reality, the jobs argument is deeply flawed. As the experts know, virtually any other activity into which such funding flowed would create significantly more jobs than Pentagon spending. A study by economists at the University of Massachusetts, for example, found infrastructure investment would create one and one-half times as many jobs as Pentagon funding and education spending twice as many.

In most cases it hasn’t seemed to matter that the jobs claims for weapons spending are grotesquely exaggerated and better alternatives litter the landscape. The argument remains remarkably potent in states and communities that are particularly dependent on the Pentagon. Perhaps unsurprisingly, members of Congress from such areas are disproportionately represented on the committees that decide how much will be spent on nuclear and conventional weaponry.

A Field Guide to Influencing Nuclear Thinking in Washington

Another way the nuclear weapons industry (like the rest of the military-industrial complex) tries to control and focus public debate is by funding hawkish, right-wing think tanks. The advantage to weapons makers is that those institutions and their associated “experts” can serve as front groups for the complex, while posing as objective policy analysts. Think of it as an intellectual version of money laundering.

One of the most effective industry-funded think tanks in terms of promoting costly, ill-advised policies has undoubtedly been Frank Gaffney’s Center for Security Policy. In 1983, when President Ronald Reagan first announced his Strategic Defense Initiative (which soon gained the nickname “Star Wars”), the high-tech space weapons system that was either meant to defend the country against a future Soviet first strike or — depending on how you looked at it — free the country to use its nuclear weapons without fear of being attacked, Gaffney was its biggest booster. More recently, he has become a prominent purveyor of Islamophobia, but the impact of his promotional work for Star Wars continues to be felt in contracts for future weaponry to this day.

He had served in the Reagan-era Pentagon, but left because even that administration wasn’t anti-Soviet enough for his tastes, once the president and his advisers began to discuss things like reducing nuclear weapons in Europe. It didn’t take him long to set up his center with funding from Boeing, Lockheed, and other defense contractors.

Another key industry-backed think tank in the nuclear policy field is the National Institute for Public Policy (NIPP). It released a report on nuclear weapons policy just as George W. Bush was entering the White House that would be adopted almost wholesale by his administration for its first key nuclear posture review. It advocated such things as increasing the number of countries targeted by the country’s nuclear arsenal and building a new, more “usable,” bunker-busting nuke. At that time, NIPP had an executive from Boeing on its board and its director was Keith Payne. He would become infamous in the annals of nuclear policy for co-authoring a 1980 article at Foreign Policy entitled “Victory Is Possible,” suggesting that the United States could actually win a nuclear war, while “only” losing 30 million to 40 million people. This is the kind of expert the nuclear weapons complex chose to fund to promulgate its views.

Then there is the Lexington Institute, the think tank that never met a weapons system it didn’t like. Their key front man, Loren Thompson, is frequently quoted in news stories on defense issues. It is rarely pointed out that he is funded by Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and other nuclear weapons contractors.

And these are just a small sampling of Washington’s research and advocacy groups that take money from weapons contractors, ranging from organizations on the right like the Heritage Foundation to Democratic-leaning outfits like the Center for a New American Security, co-founded by former Obama administration Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michèle Flournoy (who was believed to have the inside track on being appointed secretary of defense had Hillary Clinton won the 2016 election).

And you may not be surprised to learn that Donald Trump is no piker when it comes to colluding with the weapons industry. His strong preference for populating his administration with former arms industry executives is so blatant that Senator John McCain recently pledged to oppose any new nominees with industry ties. Examples of Trump’s industry-heavy administration include Secretary of Defense James Mattis, a former board member at General Dynamics; White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, who worked for a number of defense firms and was an adviser to DynCorp, a private security firm that has done everything from (poorly) training the Iraqi police to contracting with the Department of Homeland Security; former Boeing executive and now Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan; former Lockheed Martin executive John Rood, nominated as undersecretary of defense for policy; former Raytheon Vice President Mark Esper, newly confirmed as secretary of the Army; Heather Wilson, a former consultant to Lockheed Martin, who is secretary of the Air Force; Ellen Lord, a former CEO for the aerospace company Textron, who is undersecretary of defense for acquisition; and National Security Council Chief of Staff Keith Kellogg, a former employee of the major defense and intelligence contractor CACI, where he dealt with “ground combat systems” among other things. And keep in mind that these high-profile industry figures are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the corporate revolving door that has for decades been installed in the Pentagon (as documented by Lee Fang of the Intercept in a story from early in Trump’s tenure).

Given the composition of his national security team and Trump’s love of all things nuclear, what can we expect from his administration on the nuclear weapons front? As noted, he has already signed on to the Pentagon’s budget-busting $1.7 trillion nuclear build-up and his impending nuclear posture review seems to include proposals for dangerous new weapons like a “low-yield,” purportedly more usable nuclear warhead. He’s spoken privately with his national security team about expanding the American nuclear arsenal in a staggering fashion, the equivalent of a ten-fold increase. He’s wholeheartedly embraced missile defense spending, pledging to put billions of dollars more into that already overfunded, under-producing set of programs. And of course, he is assiduously trying to undermine the Iran nuclear deal, one of the most effective arms control agreements of recent times, and so threatening to open the door to a new nuclear arms race in the Middle East.

Unless the nuclear spending spree long in the making and now being pushed by President Trump as the best thing since the invention of golf is stopped thanks to public opposition, the rise of an antinuclear movement, or Congressional action, we’re in trouble. And of course, the nuclear weapons lobby will once again have won the day, just as it did almost 60 years ago, despite the opposition of a popular president and decorated war hero. And needless to say, Donald Trump, “bone spurs” and all, is no Dwight D. Eisenhower.

To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.

You might perpetuate misogyny if you say this to a girl

(Credit: AP)

Sexual assault has arguably become the hot-button issue of the fall. Harvey Weinstein’s fall and the #MeToo social media movement have awakened many Americans to the reality that almost every woman has encountered sexual harassment or assault at some point in her lifetime. Now many parents are asking how they can protect their daughters from becoming victims and their sons from being perpetrators. Sexual harassment and assault are highly pervasive among children. According to a 2011 study, 56 percent of girls reported having experienced sexual assault while in school. One piece of advice some parenting experts are giving is: stop telling adolescent girls that boys are mean to them “because they like you.” It’s an outdated response that normalizes male aggression against women at a dangerously young age.

The aforementioned study also shows how normalized sexual assault is in the eyes of offenders: 44 percent of the students who admitted to sexually harassing others didn’t think of it as a big deal, and 39 percent said they were just “trying to be funny.” Clearly, sexual harassment and assault is a silent presence among today’s children, and when parents tell their daughters to ignore or tolerate it, they prop up a devastating cycle of violence. For far too long, American parents have tolerated aggressive behavior in boys. Even implicitly, adults condone violence in boys; studies show that parents are more tolerant of boys who act aggressively toward peers and siblings than of girls who do the same.

Teaching girls to speak up when they are violated is a cornerstone of the third wave of feminism. Parenting expert Robyn Silverman, host of the podcast How to Talk to Kids About Anything, explains that parents who tell girls that boys are being mean to them because they like them actually disempower their daughters from speaking out when they are put in painful situations. “It tells them that they shouldn’t complain about the conduct because, even though the delivery is hurtful or uncomfortable, it’s ‘nice’ to be liked—and isn’t that what all girls are supposed to want? It all at once excuses the ugly behavior, gives it a favorable label and silences the girl.”

Silverman continues, “The message is insidious, the most atrocious kind of earworm that rings inside a girl’s head as she continues to interact with boys: their behavior is OK because the reason for their actions is seen as favorable.”

Also, when parents tell their daughters that boys mistreat them because the boys find them attractive, the adults create an unhealthy connection between sex and violence for these girls. As Heather Hlavka of Marquette University explains, in a recent study, “young women overwhelmingly depicted boys and men as natural sexual aggressors, unable to control their sexual desires. Girls normalized their experiences of sexual harassment and abuse because they were so common and indiscriminate; ‘that’s what boys do’ and ‘they do it to everyone.’” It’s all part of a normalization of male violence that begins in childhood and is hushed up by parents who don’t connect the dots to later male aggression.

This bad advice also enforces dangerous and rigid gender roles in kids. Slate’s Melinda Wenner Moyer recently asked how parents can shield children from sexism early on. As it turns out, not much is under parents’ control, although parents can do their best to keep from enforcing gender stereotypes. When children adhere strongly to common perceptions about gender, they become tied to a system of typecast sexual roles. As early as their teen years, “adolescents with strong gender stereotypes start to believe that boys are constantly seeking out sex and that girls should strive to look pretty and seek boys’ sexual attention.”

The lessons children learn about gender violence can greatly impact them later in life. Young girls who are taught to believe that aggression and bullying from boys is an indication of affection can go on to date men who mistreat them. Boys are negatively affected, too. We’ve already known for years that young boys who see assault normalized when their fathers hurt their mothers are more likely to hurt their own partners or spouses later on in life. As Moyer writes for Slate, “studies also find that the more strongly boys believe [gender] stereotypes” like the notion that bullying girls is OK, “the more likely they are to make sexual comments, to tell sexual jokes in front of girls, and to grab women.”

Sexual assault and consent can be difficult subjects to broach with children, but these topics are crucial to bring up. Silverman explained how parents can take action early on to encourage their daughters to speak up when they’re touched or spoken to inappropriately. “As a parent myself, I have looked both my daughter and son in the eyes and told them: If someone is touching their private body without their consent, this is not okay and they should speak up. If they are touching someone else’s private body without consent, this is not okay and they should stop. And yes, if they see this behavior in action, they should speak up, stop it or speak to someone else who can stop it. These are messages both boys and girls need to hear. And they need to hear it early.”

Liz Posner is a managing editor at AlterNet. Her work has appeared on Forbes.com, Bust, Bustle, Refinery29, and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter at @elizpos.

Solar “microgrids” like Tesla’s aren’t a fix for Puerto Rico

A section of collapsed road after Hurricane Maria, October 7, 2017 in Barranquitas, Puerto Rico. (Credit: Getty/Joe Raedle)

In addition to its many other devastating human consequences, Hurricane Maria left the island of Puerto Rico with its power grid in ruins. Power was knocked out throughout the island, with an estimated 80 percent of its transmission and distribution wires incapacitated. When hospitals and other critical users could not get backup power and water supplies ran low, an extended outage became a humanitarian crisis that has yet to be resolved.

This shameful outcome should have been avoided with strong, swift federal leadership. Yet more than five weeks after the storm, only about 40 percent of the grid has been rebuilt, and service remains unreliable even where power is restored.

As the recovery process inches its way forward, the questions many are asking go like this: Why are we rebuilding the grid to be the same as it was before the storm? Can’t we use this as an opportunity to create a more modern, resilient, renewable power system? Isn’t this the perfect opportunity for an upgrade?

The answer to these questions, from my perspective having worked with and researched the power industry for four decades, has little to do with technologies and everything to do with some nearly insurmountable financial and governance challenges. There is a path forward, but it will not be easy.

The power system before Maria

Prior to Maria, Puerto Rico had one of the largest public power authorities in the U.S., known as PREPA, serving a population of 3.4 million people from 31 power plants, 293 substations and 32,000 miles of wire. Almost half its generation was from old, very expensive oil-fired plants, resulting in prices about 22 cents per kilowatt hour, among the highest in the U.S. The island has several solar photovoltaic farms but gets about 46 percent of its power from oil and only about 3 percent from solar.

At the center of all this is PREPA and its outsized role in Puerto Rico. With US$9 billion of debt, PREPA has been part of the contentious refinancing process that ultimately required congressional action. PREPA is also the largest employer on the island, with strong connections to the island’s leadership, so proposals perceived to adversely impact PREPA can be difficult to enact. Recently the island has established a new energy commission called PREC with oversight over PREPA’s plans, spending and rates.

Hurricane Maria knocked out long-distance transmission lines that transmit power from more remote parts of the island in addition to local utility poles.

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

The PREC’s efforts at reform underscore the enormous challenges the utility faces. In September 2016 the PREC issued an order directing PREPA to convert some of its oil plants to gas, renegotiate some high-priced renewables contracts and purchase more renewable energy.

In April 2017 PREPA issued a new financial plan with starkly grim prospects: a $4 billion maintenance backlog, the loss of fully one-quarter of its sales in the next 10 years, and continued red ink as far as the eye can see. Meanwhile, renewable power developers who have tried to build plants on the island have encountered great difficulties, as chronicled in this blog post.

Then, just before Maria, PREPA declared bankruptcy. Maria therefore destroyed the grid of a system that was already bankrupt, having trouble maintaining its service and paying its bills, resistant to renewable interconnections, and politically difficult to reform.

Proposals for rebuilding with microgrids

The challenge, then, is to 1) restore energy access as quickly as possible; 2) begin to build a long-term resilient and operable grid; and 3) reform a broken regulatory system. In the wake of the storm, clean energy experts and businesses saw this as the perfect opportunity to start over.

“Puerto Rico will lead the way for the new generation of clean energy infrastructure,” one solar CEO asserted, “and the world will follow.” Elon Musk also famously tweeted an offer to solve the island’s energy problems with Tesla solar systems and batteries.

With an array of solar panels and batteries, a group of buildings, such as a hospital, or a neighborhood can power itself and operate independently in the case of an outage with the central grid – called “islanding” in industry parlance.

Provided they can be paid for and operated safely, quickly setting up these solar microgrid systems is an excellent measure that is both stopgap and long-term contributor. These systems can be set up in a matter of days, providing enough power to help neighborhoods with critical power needs, such as cellphone charging, powering cash machines and providing electricity service for health care and first responders.

However, these systems cost tens of thousands of dollars, and there is currently no substantial way to pay for them other than the kindness of strangers. Three-and-a-half million people would need perhaps 350,000 of these systems – at a price tag in the billions – to provide only a fraction of most families’ power needs.

Even if costs were not a consideration, these distributed systems aren’t a substitute for the grid. Many people think that microgrids don’t need poles and wires, but if they serve more than one building they use pretty much the same grid as we use today.

Once the grid is rebuilt, the new grid-independent systems should then become part of a series of new community microgrids, or networks of multiple solar panel installations backed up by storage. These interconnected systems would be able to “island” together to keep the whole community running at partial if not complete levels of service. With the necessary planning and approvals, new community power organizations could be set up – perhaps separate from PREPA – to finance the conversion of local grids to a more resilient form.

So there is a path from the current grid to one that is far cleaner and more resilient, but it’s not simple or quick. It would require melding complete and rapid restoration of power with a major infusion of capital.

Changing the base of generation from PREPA’s aging, inefficient fleet to clean sources is an essential part of this path. However, even at an extremely fast pace, it takes months to plan the economics, financing and engineering of this transition. More commonly, it takes years and careful economic and financial planning to raise the billions of dollars of capital needed and then spend it wisely.

A sustainable, resilient path forward

Puerto Rico’s citizens have endured great hardship and tragedy. We as a society certainly owe it to them to do whatever we can to lessen the damage from the next hurricane and speed power restoration. However, the path to a sustainable and resilient grid for the island is not as simple as air-dropping solar panels and other equipment onto the island and assuming all will be well. The suggestion that restoring power by replanting the current poles and wires will foreclose a more distributed solution isn’t correct, nor is it the most equitable way to restore power to everyone as quickly as possible.

This isn’t to say that the installation of fully independent solar systems and microgrids should be discouraged in any way. With the important provision that the hardware is maintained properly, the more solar and storage we can get onto the island sooner the better.

At this point, Puerto Rico’s grid is being rebuilt essentially as it was before.

But even as the grid is rebuilt as quickly as possible, the planning and engineering should begin on how to migrate the grid to smaller sections that self-island. This must include all the main aspects of power system development and operation, including financing, ownership, operation and maintenance of the systems.

The only logical way for Puerto Rico – and every other storm-prone electric system – to become a series of resilient and clean microgrids is to first get the entire grid functioning and then to create sections that can separate themselves and operate independently when trouble hits.

Dr. Fox-Penner thanks Scott Sklar, Phil Hanser, Sameer Reddy, Thomas McAndrew and Jennie Hatch for input. All errors are his own.

Dr. Fox-Penner thanks Scott Sklar, Phil Hanser, Sameer Reddy, Thomas McAndrew and Jennie Hatch for input. All errors are his own.

Peter Fox-Penner, Director, Institute for Sustainable Energy, and Professor of Practice, Questrom School of Business, Boston University

November 14, 2017

Shooting spree in Northern California leaves 4 dead, children injured

An unidentified woman, right, is comforted by an investigator at the Inland Regional Center, the site of shooting rampage that killed 14 people, Tuesday, Dec. 8, 2015, in San Bernardino, Calif. (Credit: (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong))

Another gunman has opened fire at random in America.

A gunman who indiscriminately picked targets during a shooting spree in Northern California on Tuesday morning killed at least four people. Several people and places, including an elementary school, were targeted in the community of Rancho Tehama Reserve, about 130 miles north of Sacramento.

The shooting is the latest in a string of violent episodes across the U.S. which have included Las Vegas and Southern Texas.

A total of ten people were injured during the spree, including two children. The unidentified gunman fired at an elementary school and a woman driving her kids to school in the rural area.

according to the Washington Post, the gunman was shot and killed when law enforcement arrived on the scene. No children were killed during the shooting spree.

“It was very clear early on that we had a subject that was randomly picking targets,” Phil Johnston, an assistant sheriff in Tehama County, told reporters, according to the Post.

The incident occurred just shortly after 8 a.m. when police were hit with “multiple 911 calls of multiple different shooting sites, including the elementary school” in Rancho Tehama Reserve, less than 200 miles north of Sacramento.

There is no currently known motive behind the attack and the identity of the shooter is still being confirmed, but authorities said they found two handguns and a semiautomatic rifle, and the shooter was previously known to law enforcement, the Post reported.

Johnston said “there was a neighborhood dispute ongoing” but that authorities still didn’t “know what the motives are for this individual to go on a shooting spree.” Johnston also said neighbors told authorities “there was a domestic violence incident” that had involved the shooter.

The shooting is just the latest in what is already the deadliest year for mass killings in the U.S. in more than a decade. While tragedies and bodies continue to pile up, there has been little talk of increasing gun control on Capitol Hill.

Bill Gates is building his own city — no democracy required

Bill Gates (Credit: Getty/Jamie McCarthy)

Stop me when this sounds like a plot dreamed up by a Bond villain: The richest man in the world announced in a press release his intent to invest $80 million to buy 40 square miles of land just 45 minutes west of Phoenix. He and his investors want to build around 80,000 residential units and thousands of acres of commercial and industrial buildings to create their own “smart city,” dictated on their own terms and planned without any input from, oh, you know, the people who are going to actually live there — in other words, no pesky democratic planning getting in the way. The city will embrace the sort of techno-utopianist goals that sound good on paper but never yield any tangible social results besides buttressing the egos of the Silicon Valley cult. And the best part: the city-to-be — Belmont — is literally named after the firm that is investing in it, Belmont Partners.

If this sounds like a fiefdom, well, it kinda is. Weaving his own funds through a few different holding companies, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates is proposing to build a town based on his personal beliefs as to what makes society great. Aside from their slight political differences, that sounds vaguely like our president’s moralistic vision for the world, no? It’s an unusually top-down way of engineering a place where people will actually live and work and breathe and think, and bucks the democratic rules that govern most cities in the Western world.

Gates’ dreams of planning his own city are not that unusual for people cut from the same cloth. There’s a long, dark history of billionaires and/or corporations trying to design “utopias” themselves, without democratic input. (Mike Davis edited a book called “Evil Paradises” that may be the premiere account of this phenomenon.) By dint of The Walt Disney Company’s presence, Florida has multiple experiments of the sort: most of us have heard of Celebration, Florida, the master-planned suburban community designed and developed by the corporation. But more sinister than Celebration, there’s also Lake Buena Vista and Bay Lake, two small cities whose politics and even tax bases are entirely controlled by the Walt Disney Corporation.

A 1993 Washington Post article on the bizarre politics of these two cities describes how the Florida government “gave the Disney organization extraordinary powers, rights and privileges” to manage and control them. This includes exemption from building regulations, the power to freely annex private land, the power to “issue millions of dollars worth of tax-exempt municipal bonds to pay for improvements on Disney’s property,” and, darkly, “authority to detain anyone deemed to be ‘causing a public nuisance’ or to forcibly remove from Disney’s property anyone the company regards as undesirable.” Plus, “the law exempts Disney from being accused (much less convicted) of false arrest.” Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista are essentially police states run by The Mouse.

Techie efforts to control civics mirror Disney’s imperious ambitions. There’s a deep-seated belief in libertarian-rampant Silicon Valley that the government and our political processes are slow and messy; to that end, many techies, mad with power, have attempted to start their own partially or fully-privatized cities. These vary in terms of ambition: real-life super-villain Peter Thiel is one prominent donor to the Seasteading Institute, which promises to build floating “libertarian island” cities free of government regulation. Most terrifying, SpaceX and Tesla CEO Elon Musk is rabidly pursuing his chance to dictate the terms of his own privatized Marian utopia, funded by selling extra-planetary tourism packages to the rich.

But going back to Belmont: this kind of anti-democratic ambition isn’t new for Gates. His entire philanthropic vision, exemplified by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is predicated on the idea that rich people and technocrats know best how to manage the levers of society, and the rest of us peons should sit back and let the rich techies run our lives. Billionaires like Gates, who spend much of their lives surrounded by yes-persons, believe they know better than everyone else how things should be; Silicon Valley, similarly, is encased by a reality distortion field that believes technology and progress are one and the same, a fairly dangerous belief that history belies.

If Gates were actually taxed fairly on the income that other people make for him, we might get to collectively decide where and how to allocate the resources from that wealth; instead, he gets to build his own Belmont on his own terms, imprinting his own beliefs about what a virtuous utopian city would look like. It’s a great PR campaign for him and lousy for everyone else. But that’s the difference between charity and solidarity, to paraphrase Eduardo Galeano: charity is a relationship of top-down control, the rich dictating how the rest of us live. Solidarity is when we decide for ourselves.

If Belmont attracts a self-selecting crowd of residents, much like Celebration, Florida, then it could perhaps become a temporary “success” in the same way that lily-white Celebration is a success. Steven Conn chronicled how the draw for many Celebration residents was actually the lack of a normal democratic character of a city; indeed, those who came often preferred to have their lives managed by a publicly-traded corporation. As Conn wrote (emphasis mine):

For many residents, the attraction of Celebration was the promise that Disney would control the environment of the town just the way it had made its amusement parks the happiest places on earth. Residents contract privately for services, and the town’s Architectural Review Committee strictly regulates the physical appearance of the place. “Most of us came here not because of Disney,” resident Kathleen Carlson told the Miami Herald; “we came because we wanted that type of control over our neighborhood. You don’t have to worry that your neighbor will suddenly start parking an old pickup on his front lawn.” Celebration has substituted corporate control for democratic participation in the life of the town. It is hardly the sort of reinvigorated “community” new urbanists hoped they could create, but exactly the result one might expect, given the way “community” has been turned into a real-estate asset.

But Celebration didn’t stay this way. Like any city, it was subject to the greater economic vicissitudes, which private contractors couldn’t manage away. Conn continues:

When the Great Recession settled into Florida, however, not even Disney could control real estate values inside its model town. By the end of 2010, property prices had dropped even more than they had in the rest of the state—in some cases as much as 60 percent—and foreclosures were happening more frequently as well. In the space of a week at the end of 2010, the town experienced its first murder and then the suicide of a resident who had barricaded himself in his home and held a SWAT team at bay for fourteen hours. Stunned, much like residents of Reston had been when drugs and violence had come to that model town a generation earlier, Celebrationites had to confront reality.

Billionaires would be wise to learn from Celebration: you can’t engineer utopia.

Jon Bernthal plays “Marvel’s The Punisher” and it is a brutal binge

“Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan”: Inside 5 new must-read books

For November, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to five authors with new books: Eileen G’Sell (“Life After Rugby“), Garth Risk Hallberg (“A Field Guide to the North American Family“), Bill McKibben (“Radio Free Vermont“), Richard Thomas (“Why Bob Dylan Matters“), and Kevin Young (“Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News“).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Eileen G’Sell: Beautiful secrets and bloody feet. Marathon finish lines ribboned in loss. Learning how to spell “laughter” correctly.

Garth Risk Hallberg: The binoculars on the cover could have been a kaleidoscope: inside is 21st-century family life seen through the crazy swirl of all the books I loved when I was 24. It’s like my attempt to mediate in my parents’ divorce. My parents John Cheever and Gertrude Stein.

Bill McKibben: Standing up (via sitting in), local beer, late-‘60s non-Motown soul music, the roots of podcasting and/or the natural successors to Paul Harvey and, mostly, resistance.

Kevin Young: Art, truthiness, pseudoscience, hoaxing, fake news, race, and humbug in American life and history.

Richard Thomas: The genius of Bob Dylan across more than half a century, poetry and song, folk, blues, gospel traditions, the art, how a classic comes into being, aesthetics of melancholy, faith, life, love, death, performance artistry, how experience, observation and imagination conspire.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

McKibben: When I was a boy I lived in Lexington, Massachusetts, and my summer job involved donning a tricorne hat and giving tours of the Battle Green, whereon began the fight against imperialism and colonialism. It taught me early on that there was nothing unpatriotic about dissent; rather, the opposite.

Young: Tom Sawyering as a verb, girl wonders, spirit photography, the OED, poetry, fairy tales, hysteria, “race science,” euphemism, the movie “Time After Time” from 1979, captivity narratives, commonplace books and Parliament-Funkadelic.

Thomas: Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan, Homer, Virgil, Ovid, Dante, T. S. Eliot, folk music, Woody Guthrie, singing and thinking about Dylan across 53 years, old girlfriends, wife, daughters, life and life only, Dylan bootlegs, concerts.

G’Sell: French asceticism and French New Wave. Classical ballet and police brutality. Getting hit by a car and smashing the windshield while wearing a magic hoodie. Late ’80s sugar cereals that have managed to survive.

Hallberg: Well, there’s a force that pulls things together and a force that blows things apart. At the time of the writing, in 2003, I felt like fragmentation had the upper hand, in life and in art. But I grew up Episcopalian, so I felt — still feel — this need to draw things together under one roof. To say, no, you belong here, experimental French thing, and you, too, domestic realism. And you especially, “Choose Your Own Adventure.” Talk amongst yourselves.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Hallberg: Third graders: people on whom nothing is lost. Me: their teacher. Ha, ha. Also: terrorism, anthrax, Iraq War, D.C. sniper, months we couldn’t use the playground, running zigzag across parking lots to frustrate bullets. And drinking. Giving way to writing. Alertness, rawness, sadness, funniness. Lifeness. Meditations in an emergency.

McKibben: Being put in handcuffs/paddywagons with some regularity; failing to save the planet.

G’Sell: Living alone in Berlin before the Palast der Republik was torn down. Living with someone in Barcelona and feeling suddenly alone. Making a living, living large, retiling my Midwestern kitchen floors. Calculating the area of a scalene love triangle. Protesting in the streets, tripping on my laces, and road tripping thousands and thousands of miles in a rental car with my dog.

Young: An election or two. Archives. Fake news. Black Lives Matter. Raising kids and myself.

Thomas: Thanksgiving, Christmas, singing protestant hymns every Sunday, starting the day with coffee and expectingrain.com, teaching three spring courses with May 1 book deadline, Dylan concerts in Florida, New York, Rhode Island, walking dogs in Webster Woods, eventually seeing it was going to work.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Young: I generally try not to read reviews. But people sometimes call me “prolific,” which I’ve come to accept.

Thomas: “Pessimistic.” My day-job writing deals a lot with “melancholic” aspects of poets like Virgil and Horace — and now Dylan — a much better word, and an optimistic word.

Hallberg: I have complicated feelings about “ambitious.” Like, I don’t want to read anything that’s not ambitious. But then if something was successful, would you even notice the ambition? Then again, “successful” is a word that really gives me hives. If you’re succeeding, maybe you’re not trying hard enough.

McKibben: Unrealistic.

G’Sell: “Confessional.” I have nothing to confess. And my work is only loosely autobiographical. Smuggling a shiny set of ovaries does not a confessionalist make. I love a lot of confessionalist writing. But that’s not what I do.

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Hallberg: Rhythm guitar. No, wait — irrespective of talent, right? B-boy.

Thomas: Being Bob Dylan. Or a lumberjack.

G’Sell: Stunt double or neonatologist.

McKibben: Cross-country ski racer.

Young: Guitarist for a good band, or bassist for a bad one.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Thomas: I generally write for people who study Greek and Latin, with too many footnotes. Not sounding too academic is a goal.

McKibben: Sometimes I’m funny. I can’t bear to write about or imagine violence/people getting hurt, which might limit possible plots.

G’Sell: As a culture critic and long-time teacher of how to spin a sentence, I think my work displays (flaunts?) a dexterity — or audacity — with punctuation more common to prose than contemporary poetry. I would like to be better at not relying on that dexterity to seem intelligent and sophisticated.

Hallberg: I guess character is where I start, and everything beyond that is a mystery. I remember part of the formal dare here was to write a book without dialogue, because I was so bad at it. I failed, but learned a lot about dialogue in the process.

Young: Brevity.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

G’Sell: I pretend I am Donald Hayne, the guy who played the Voice of God in “The Ten Commandments.” #burningbushforever

Hallberg: Well, I’m drawn to all the unpublishable lengths — triple-decker, novella — so I guess I try to protect the reader by writing things that will never see print. Failing that, I remind myself that I’ve always been curious about what other people had to say, and to assume readers are like that, too. That’s the price of admission to the little society of readers, right? A bias toward being interested?

Young: Does curiosity count?

Thomas: Because I wrote it about Bob Dylan. He’s been reading what I — and very few others — have been reading all my life. I hope that works some.

McKibben: Sadly, my track record has been fairly good. I wrote the first book about what we then called the “greenhouse effect,” way back in 1989 — which means that those who had the good sense to listen to me then have had 30 extra years to worry about it.

Even Tom Cruise can’t save “Dark Universe” if the studio greenlights movies like “The Mummy”

Tom Cruise and Annabelle Wallis in "The Mummy" (Credit: Universal Pictures)

Last week The Hollywood Reporter revealed that Universal’s so-called “Dark Universe” — a planned cinematic universe containing classic Universal monsters like the Mummy, the Bride of Frankenstein, the Invisible Man, the Wolf Man, the Creature from the Black Lagoon and others — had been effectively cancelled. No official corporate obituary has been issued yet, of course, but with the producers cleared out and all impending projects in stasis, it’s fair to assume that the planned universe has been abandoned.

Where did they go wrong? There are actually so many ways, that it’s easier to straight-up list them.

1. They didn’t bother making a good movie.

As I noted in my review of “The Mummy,” the biggest problem with this film is that it felt like it was made by a committee. Instead of trying to tell a good story of its own — whether atmospheric and scary like the 1932 movie or action-packed and campy like the 1999 remake — this version spent more time trying to set up future Dark Universe films than being a memorable or even simply enjoyable flick of its own. When you look at movies that successfully launched modern cinematic universes — “Iron Man” in 2008, “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” in 2015 and so on — they were fun, well-crafted movies on their own that subtly planted the seeds for sequels and spin-offs. Even though the studios were planning future movies while creating the original films, they still clearly took the time and energy to attach strong storytellers (Jon Favreau, J. J. Abrams) to those projects so that they would stand on their own terms. By contrast, “The Mummy” threw everything trendy it could think of at the screen in the hope that as much of it as possible would stick. Because it had tried to stuff in so many different genre identities, it wound up lacking any distinctive mark.

2. There was no indication that anyone was clamoring for a Universal Monsters universe.

Once again, the success of the Marvel and Star Wars universes come to mind. While Iron Man and Thor may not have been particularly popular characters among casual moviegoers prior to their films, the massive successes of the “X-Men” and “Spider-Man” films had clearly established that audiences had an appetite for superhero fare. While trying to create new fanbases for more obscure characters was a risk, it was at least grounded in recent box office trends. Similarly, even though the “Star Wars” prequels wound up being maligned by fans as vastly inferior to the original trilogy, they still made bank at the box office, indicating that fans still wanted to see new installments in that universe. By contrast, the last Universal monsters property that had done well was the original “Mummy” trilogy, and even that had done little to drum up enthusiasm for more Universal monster films.

3. They don’t understand what audiences want in horror movies.

Yes, I’m not entirely sure “The Mummy” even wanted to be a horror film (which was part of the problem), but let’s assume for a moment that the Dark Universe actually wanted to deal with the darkest of all popular genres. There is a template that they could have followed — “The Conjuring,” which between its wildly successful sequel and “Annabelle” spin-off series is well on its way to launching a cinematic universe of its own.

What did “The Conjuring” do right, at least from a box office perspective? (I’ll refer you to a review by my colleague Andrew O’Hehir for a discussion on the film’s artistic merits.) For one thing, it was helmed by a man with a proven track record of success (James Wan of “Saw” and “Insidious”). It also dealt with a sub-genre that had already been proved popular (ghost films like “Paranormal Activity” and, again, “Insidious”). Finally, and most importantly, the producers took the time to see if there was a high audience demand for more movies in this universe before actually trying to make said universe.

As I noted in my review for “Thor: Ragnarok,” 2017 has been something of a redemptive year for American moviegoers. While it’s too soon to say whether this is a fluke or something more lasting, it’s clear that the public has grown adept at sensing when a film is more of a product than a work of art. This isn’t to say that every Hollywood movie isn’t first and foremost a business venture (thinking otherwise would be flat-out naive), but there is an important distinction between the ones that were still fueled by a vision and those which are artificial right down to their core.

“The Mummy” fell into the latter category and audiences, to their credit, picked up on that. If the movie had only been made with the passion of an “Iron Man” or “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” I wouldn’t need to write an article about a failed universe but could instead celebrate the launch of an exciting new world of gods and monsters.