Lily Salter's Blog, page 235

November 19, 2017

How O-Six became the “most famous wolf” in the world

O-Six (Credit: Doug McLaughlin)

“Some of us are born great, some achieve greatness, and others have greatness thrust upon them,” Shakespeare wrote in “Twelfth Night”; to that, I might add, some are never aware of their greatness but possess it anyway. Such was the case of O-Six, a female wolf who lived in and around Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, and who — thanks to a few obsessive wolf-watchers and the ubiquity of social media — managed to live as a free-roaming wolf, unencumbered of gates or walls, while still having her existence carefully recorded to the extent that fame followed her around the world.

The story of the Yellowstone wolves, and how they came to be reintroduced to the park, is a parable of politics and ecology. Humans extirpated most of the wolf population of the continental United States during the 19th and 20th centuries, as they did with other large keystone predators like the grizzly bear. In the mid-nineties, conservationists began to suspect that many of the ecological problems that Yellowstone had could be cured merely by reintroducing wolves.

And so a pilot program was born. Most scientists agree that the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone had a rebound effect on many other species; the elk population, which was overgrazing plants and grass, was reduced, resulting in some trees, like aspens, becoming healthier. The number of coyotes declined, while the number of foxes and raptors increased. And perhaps most dramatically, beavers — which were nearly completely gone from Yellowstone — made a vast resurgence.

Nate Blakeslee, a writer for Texas Monthly who lives in Austin, Texas, just published a new book, “American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West,” about the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone. In telling the story, Blakeslee chose to focus in on the issue vis-à-vis the allegory of one single wolf, O-Six. As she lived her wolf life, the human world was having political arguments over the future of O-Six and her ilk, and making policy decisions that would come to affect her as well as the ecosystem at large. I spoke to Blakeslee about O-Six, the controversy over wolf reintroduction, and how he managed to write a book about a wild animal that he never even interacted with personally. Our interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Salon: To start, what does it mean to be a famous wolf? How did O-Six get thrust in this position?

Nate Blakeslee: Yeah, that’s a strange concept. How can you be famous wild animal? How can you be both a celebrity and yet be a truly wild animal? It’s a function of the unique situation that you see in Yellowstone. Yellowstone is the one place in world where you can reliably spot wolves from the roadside with a spotting scope. Ever since they were brought back to Yellowstone in the mid ’90s, this new pastime of wolf watching has been happening in the park. Every now and then, one particular wolf will catch the watchers’ fancy. O-Six was not the first famous wolf in the park. In that first decade, there was this pack known as the Druids. I write about them a bit in the book. They were the face of the reintroduction program and several documentaries were made about them, and they were famous in their own way. But when O-Six rose to prominence, she was probably the first wolf that came to the watchers’ attention during the Facebook era, you know, when social media existed.

Interesting. So O-Six owes her fame partly to social media, the prominence of smartphone cameras?

Blakeslee: You had all these visitors, these tourists taking pictures and video, and posting accounts of what they saw her do online, and so her legend spread that way virally, online. Then, eventually, she just became one of the attractions in the park — something you would come to see, like Old Faithful. There are guide services in the park that will take you on wolf-watching tours, and she became a staple of those.

Wolves are often very solitary or don’t like attention. Can you actually schedule and see her reliably or she doesn’t shy away from tourists?

Blakeslee: Well, you’d have to get a little bit lucky. I mean, the most popular area to watch wolves is this wide-open, relatively treeless valley in the northeast section of the park, called the Lamar Valley. That’s where they were first brought back when they were reintroduced in the ’90s. To [scientists’] surprise, the wolves did stay there and they didn’t seem to mind the fact that there was this road and there were cars and people standing along the road. They didn’t approach cars and people, but they became tolerant of them, willing to live their lives within a mile or two of the road.

Keep in mind the tool that [wolf-watchers] used to observe these wolves. It’s not like a regular pair of binoculars. They use a telescope mounted on a tripod. They call them spotting scopes. You can watch a pack of wolves that is three, even four miles away, and see everything that they’re doing. If they’re only a mile away, you can see everything. You can see the expressions on their faces.

That’s why it’s possible for people to become so familiar with one particular wolf and feel like they get to know her personality — and you get this sense of intimacy, even though you never really get that close to the wolf.

For someone who might not know much about the history of wolves in the U.S., can you explain why they were brought back to Yellowstone?

Blakeslee: Wolves had all been hunted out essentially by the end of 19th century, out of the Northern Rockies, just as they had across the vast majority of the lower 48 states. They had been trapped out by fur trappers or later hunted out by ranchers to protect livestock. [In the continental U.S.] they were only found on the margins — the upper peninsula of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota. Everywhere else, they were essentially gone.

And in Yellowstone, there was this enormous explosion in the elk population, because elk is what the wolves had preyed on there for thousands of years. [The elk population explosion] was so dramatic that it started to degrade the habitat. The park rangers responded by starting to cull the elk themselves. They basically replaced wolves with guns, and there were thousands of elk being killed every winter when there were no visitors around to see it. It became like Yellowstone’s dirty secret.

Many believed wolves would be a more holistic way to fix this problem, this broken ecosystem. That idea was first floated in the 1940s, but it was controversial then. Those same ranchers that had hunted them out are all still there. They’re still running cattle there to this day, and elk hunting is really a big business in the Northern Rockies.

Everybody in the hunting business knew that wolves eat a lot of elk. They resented the idea that this competition, basically, was going to be brought in by the federal government, who they were not too keen on to begin with. It became this federal government versus local control argument, which is really common in Western politics today. In fact, this fight over wolves is just one small part of this much broader struggle over how land in the West, public land in the West, should be used and who should get to make those decisions. That’s a long answer to a short question about why it was controversial to bring those wolves back in the first place.

Ecologically speaking, what has changed in Yellowstone since wolves were reintroduced?

Blakeslee: Everything that the biologists predicted would happen has happened. I mean, we’re 20 years into this experiment now, and wolves have completely saturated not only Yellowstone but also most of their former habitat in the Northern Rockies, which is to say in Wyoming, Idaho and Montana. Especially in Yellowstone, which has been a habitat that’s been most studied, there was a dramatic decline in the elk population [after wolves were reintroduced]. Because predation had been gone for so long, the elk in the park had stopped behaving like wild animals. They started acting more like cattle.

And elk are really big animals. They are like beef cattle with long legs, basically. They don’t live lightly on the landscape. They would congregate in valleys, they would congregate along streamsides where their preferred food was. They ate a lot of willow and a lot of aspen, stunting the growth of generations of those plants. This in turn caused degradation of the streamside, which damaged trout habitat.

Willow is food for beavers, and so the beaver habitat was damaged — and then when they brought the wolves back, all of that was reversed.

But there were also some unusual effects that maybe weren’t anticipated. Yellowstone had an enormous number of coyotes — way too many coyotes — because they had no canine competitor.

When the wolves were brought back, they immediately started killing coyotes. They killed coyotes that tried to come in and scavenge on the elk carcasses that they brought down. But also when a wolf would move into a new territory and dig a den, they would dig up any coyote dens they would find just to make the area safer for their own pups. The coyote population was cut in half in that northern range of Yellowstone where the wolves were first brought back. You saw this rebound in the rodent population. It’s all part of a jigsaw puzzle that all fits together because the coyotes were eating rodents.

But the wolves don’t eat the rodents?

Blakeslee: Right, the wolves don’t eat the rodents. They sort of play-chase of them sometimes. But it’s not a staple of their diet. They eat almost exclusively elk. The rodents came back, which brought back weasels, which brought back raptors. There was this avian renaissance in the park that nobody knew they were missing. Coyotes also killed a lot of pronghorn, that was a staple of their diet, and wolves don’t. So you saw the pronghorn bounce back.

Any time a wolf brings down a carcass, it provides food to a wide range of animals — scavengers in the park. It also provides food for grizzlies. One of the grizzlies’ main staples is these little whitebark pine nuts that they eat in the fall to get enough protein to hibernate. But the whitebark pine production had just plummeted, probably because of global warming. Biologists in the park theorized that they would now see a decline in grizzly populations, fewer cubs every year, and they were going to see less-healthy bears — and it didn’t [happen]. One theory is it’s because these elk carcasses, which grizzlies come along and steal from wolves, had just become this very tiny source of nutrition in the park [for the bears].

It’s interesting that, in addition to having a wolf population, Yellowstone also has grizzlies, right? These two different keystone predators. But they have different diets and ecological niches, right?

Blakeslee: Definitely. The wolf was a much more critical predator to lose, because grizzlies [will] eat essentially anything. [Grizzlies] will spend a whole day eating bugs and moths, they’ll eat berries. They eat grass, they’ll graze on grass like cows do. They eat protein where they can get it, but they don’t kill a lot of adult animals. They’ll kill elk calves; occasionally, [grizzlies] will run down a sick elk.

But wolves, each pack is eating an elk every three or four days. And the wolf was the most widely distributed land mammal on the planet for tens of thousands of years. Basically, everywhere in the northern hemisphere, almost everywhere, you [used to] find wolves. There is this enormous wolf-shaped hole not only in this ecosystem but in ecosystems all around the globe. We see the effects of that, of wolves having been here, but we don’t always recognize these effects. The reason an elk can run 35 miles an hour is because that’s how fast wolves can run. They can’t be faster than that because they never needed to.

And the reason elk can go straight up the side of the mountain? That was a trait developed in response to thousands of years of predation by wolves. The reason elk are so nimble, the reason moose are so big — this particular predator has shaped all of these prey animals that we see around us. We see these lingering effects of wolves.

Even our language is full of all these wolf references. We have all these wolf metaphors: “the wolf at the door,” “leader of the pack,” “wolfing” down your food. We all say them and yet none of us have ever seen a wolf.

When we were an agrarian society, wolves were just a daily fact of life. They were everywhere. If you were on the frontier, and you were trying to raise cattle or sheep or goats, the main obstacle to success for you was the wolves that were out there. They had to be, from your perspective, gotten rid of.

Let’s go back to talking about O-Six specifically. How do you go about telling the story of one wolf’s life? What kind of sources did you talk to and incorporate to get there?

Blakeslee: I read a lot of wolf books in preparation for this project. Some of them are classics I would happily read again, but I never read one that was really story- or character-based that really hooked me. That’s what I wanted to do. The only reason it was possible is because O-Six was so famous for a wild animal. For most wolves, you might not know enough details to build a story and make [them] a character. With O-Six, you did.

The reason [I could write this book] was not because of the hundreds, or thousands, or millions of people that would see her once and post a picture to Facebook, it was because of this much smaller group of these die-hard wolf aficionados; people who would come to the park every single day, track the wolves with their radio collars, get them in their scopes and then watch them for hours and hours. Two people, in particular, would take notes every single day. One of the real breakthroughs for the project was one woman, a retired school teacher from San Diego. Her name is Laurie Lyman. She lives in Silver Gate, [Montana], right outside the northeastern entrance of the park. She watched O-Six virtually every day for three years and took notes every day.

She gave me this treasure trove of materials. It was like the diary of a wolf pack. I had never seen O-Six myself in person and I felt I understood who she was as a character and why she was so beloved. I also realized that what you could do with that material is write a nonfiction book that reads like a novel, like a Jack London story. Many of the main characters are not humans but animals, but it would all be true. It was an amazing opportunity to do a different kind of writing than I had done before, and that’s what made me excited about it.

So you felt like you knew O-Six, and her personality, even though you’d never, say, petted her or “met” her.

Blakeslee: Yeah, and that was a revelation for me. I didn’t realize… well, first of all I didn’t realize how powerful these sighting scopes were. I didn’t realize that you could actually see the expressions on their faces. I thought you could just see these little dots running across, but no, you could see them and you could watch them interact with the other wolves in the pack.

Laurie was there when O-Six first met her mate and her mate’s brother. I had a scene in the book in which this trio first meet. When I say it was a treasure trove of material, it was a treasure trove of material. I mean, there was a lot of mundane stuff in there too.

The other source of notes was Rick McIntyre. He’s the park’s wolf guru. He’s the guy who was so famously obsessed with wolves that he comes to the park every single day, rain or shine, whether he’s on the clock or not, and watches wolves all day long. He has a little tape recorder and he writes down every single thing he sees. When you read through his notes, it’s like, “O-Six stood up, faced west,” or, “sniffed the ground, laid back down.” I have pages and pages of that.

Laurie’s notes were more of a summary of what she saw that day. What I would do is I would read through hers, I would pick out scenes that seemed pivotal on the life of the pack or that demonstrated some quality of wolves that was new to me and I thought would be new to readers too, and then I would go to his notes to beef up the scenes. And then I had interviews with whoever happened to be there that day to see what they remembered. Between those sources, I was able to draw those scenes pretty thoroughly, and pretty dramatically in some instances. There are just some amazing scenes and drama, the kind of stuff that cinematographers that work in Yellowstone try so hard to get on film.

How would you describe O-Six’s personality?

Blakeslee: Well, she was not cuddly. She was an extremely strong leader. She was a once-in-a-generation hunter. Wolves hunt elk, which are obviously much larger than they are. The average female wolf is about 90 pounds; and male wolf, 110, and these elk could be 500, 700 pounds.

They run them down and pull them down with their teeth, which is extremely dangerous. Wolves are often injured and killed during this process. Usually the whole pack will chase, but the females tend to be lighter and faster. They’ll run the elk to exhaustion. Then, the larger males will come around and get them by the windpipe, bust the pipe, and that’s the end of the chase. She perfected the art of doing that by herself because she was a lone wolf for an extended period of time after she left her natal pack and went out, looked for her own territory. That’s how she first really came to the attention of her watchers, is that she was so good at taking down an elk by herself. A number of people had never actually seen that before and so that was a phenomenal thing to witness.

She met this pair of yearling brothers who were also out wandering on their own, looking for a territory and a mate. She was two years older than them. They were extremely naïve. It was this puzzle to Rick and Laurie and the other watchers why she decided to hook her wagon to them. I said in the book, they were more like trainees than equal partners when she brought them on. They really didn’t know how to hunt. She basically had to train them as if they were her own pups. She was the unmistakable leader of that pack and continued to be throughout the three years that she ruled over the Lamar Valley.

O-Six was also capable of empathy, as are all wolves. The scenes at the den are just remarkably tender scenes. Empathy is a trait that we associate with people. You might be tempted to say, “well, that’s anthropomorphizing.” But unlike mountain lions or bears or creatures that spend 90 percent of their life alone, wolves spend almost all of their time in the company of other wolves. They learn how to cooperate with other wolves because they hunt collectively, they feed the pups collectively, they defend the territory collectively. The ability to get along with other wolves, to read their emotions and respond accordingly, is a trait that has been selected for, just like speed or that marvelous sense of hearing that they have, or agility or strength. You can see it. You can see it through the scope. You can see wolves taking care of one another and you can see wolves taking care of pups, playing with pups. You can see all kinds of remarkable instances of that in sometimes really surprising in unexpected ways.

So if O-Six and her pack are like the protagonist, who would you describe as the antagonist?

Blakeslee: Well, the book is narrating O-Six’s personal story, but it also leaves the park and it tells the story of this struggle going on in the courts and in Congress over how wolves ought to be managed. The reintroduction program was so successful and wolves spread so far and wide that by, let’s say, 2005, the debate was over whether or not it was time to start hunting them again, whether the program was a success and they no longer needed federal protection and we could allow the states to manage them however they wanted, which inevitably would mean a hunting period. That fight was going on the whole time that we were following the life of O-Six.

It culminates finally in the first legal hunting season in Idaho and Montana and then eventually in Wyoming. I guess you would say the antagonists are those state politicians who never agreed with the policy goal, and bringing wolves back to begin with, and who did everything they could to get them off the endangered species list, to get hunting going just as fast as they could.

Then, I wanted to have the perspective of ranchers and hunters in there, just so the readers could get the full of story the politics around the issue.

[Note: book spoilers follow.]

There was one person in particular, a hunter who lived east of the park in Crandall, and … I’m not going to beat around the bush. The climax of the book, sadly, is O-Six briefly taking her pack east of the park into this area known as Crandall, this national forest area where hunting is allowed. All the packs in the park will leave the park from time to time; they roam really wide, their range is huge. She happened to take them east of the park during that first legal wolf hunting season in Wyoming. She was one of the first wolves shot in Wyoming legally in 50 years at least.

There was an enormous backlash [after she was shot]. It was in the New York Times. Soon, it was around the world. The world’s most famous wolf shot in Yellowstone. Everybody was talking about whether or not wolves ought to be hunted. It was irresistible for reporters, like who could’ve imagined that one of the first wolves shot during Wyoming’s legal hunting season was the park’s most celebrated animal, arguably the world’s most famous wild animal.

The guy that shot her did not give any interviews. Why is it they kept his name out of the paper? So that he wouldn’t be the next Cecil the Lion killer, maybe. But when I finally came calling, which is about a year and a half to two years later, he had changed his mind and he was ready to talk. He was ready to tell his side of the story. I knew that readers wouldn’t want to hear it.

I know that my reaction and a lot of people’s reaction, when they read in the Times that O-Six had been shot, was, “Who would do such a thing and why?” The only way to answer that question is to find the person that did it and ask them. That’s what I did. He agreed to a series of interviews over the course of the year in his little cabin. It was an extremely surreal experience for him. He shot this wolf just after dawn by himself in one of the remotest places in the lower 48. He had no idea he was shooting a famous animal. He didn’t even know it was Yellowstone wolf. She was wearing a research collar by then, but in the wintertime the collars are hard to see because their coats get really thick. He killed her at like 200 yards. He couldn’t even see the collar. The next day, the whole world is talking about what he did, judging what he did. And so, it was a very surreal experience for him, and very frustrating, and he was ready to talk. His story and his perspective is in the book, too.

# # #

Blakeslee’s book, “American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West” is available now from Crown Books.

“The Martian” author calls on science nerds to challenge his Google facts

Science fiction writer Andy Weir may be single-handedly restoring the sort of “hard” science fiction that was popular in the 1950s and ’60s — the kind that focuses heavily on scientific detail — to a place on the bestseller list.

As with his debut novel, “The Martian,” Weir wrote his latest book, “Artemis,” with an eye toward scientific accuracy. All the technology in this book about a world in which humans have colonized the Moon, Weir says, is technology that already exists, but simply isn’t affordable enough — yet, anyway — to be used in the way that Weir imagines.

When he sat down with me on “Salon Talks,” Weir talked about his process for verifying technological details and some of the challenges that come with promising his readers scientific accuracy. “There are people all over who would be more than happy to help me out” when writing his books, Weir said.

Since he published “The Martian,” which went on to be adapted into an acclaimed movie starring Matt Damon, Weir befriended a number of people in the aerospace world, including people working for NASA.

But instead of picking up the phone to call those people and ask for help, Weir said, “I still found that it’s just faster just to google.”

“It’s actually one of the easiest things imaginable to research,” he added, pointing out that engineers and scientists “are very proud to work on” space technology and are happy to put their research on the internet for others to marvel at.

People don’t nitpick the science in science fiction stories like “Star Trek” or “Star Wars,” Weir said, but with his books, readers often see it as a game to test his accuracy. Watch the video above to hear Weir’s challenge for science buffs with his new book.

Watch our full interview on Facebook.

Tune into SalonTV’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

November 18, 2017

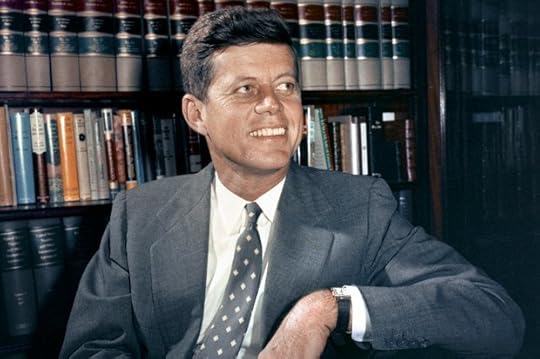

5 of the most important JFK files the CIA is still hiding

John F. Kennedy (Credit: AP)

The government’s release of long-secret JFK assassination records is generating headlines and hype worldwide. But the truth is the majority of the JFK files that were supposed to be released last month remain secret — and may forever if the CIA has its way.

On October 24, President Trump tweeted that “JFK files are released long ahead of schedule,” which was not true.

In fact, as Rex Bradford, president of the Mary Ferrell Foundation, pointed out in WhoWhatWhy, only about 10 percent of the JFK files were public by the statutory deadline of October 26. The foundation maintains an online collection of more than 1 million JFK records.

The hype continued November 3, when the National Archives posted more than 553 CIA documents never made public before, which CNN described as a “horde.” On November 9, the CIA and NSA released another batch of files, which the Washington Post called a “huge trove.”

But as Bradford told AlterNet this weekend, the impressive-sounding numbers lacked context. Even after the latest file dump on November 9, at least two-thirds of the never-seen JFK files that were supposed to be released — some 2,538 records — remain secret, according to the foundation’s analysis.

At least one-third of the JFK files that were previously released with redactions — a total of about 12,000 files — have still not been made public in unexpurgated form, he said.

Unlike mainstream news organizations, the Mary Ferrell Foundation monitors the National Archives database for the latest information on what has and has not been released. Bradford called the releases so far “a big roiling mess.”

What Are They Hiding?

The still-secret files document the careers of five top CIA officers implicated in the events that culminated in the murder of the popular liberal president in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1863.

The publicly available portions of these files do not contain “smoking gun” proof of conspiracy. But they do refute the official story that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone and unaided. While incomplete, the new JFK files show that Oswald did not act alone in the years, months and weeks leading up to Kennedy’s murder. The files confirm he acted while being monitored and surveilled by top undercover CIA officers.

Four of these five officers knew of Oswald’s personal history, foreign travels and contacts with a presumed KGB officer in Mexico City six weeks before Kennedy was shot and killed. They include:

1. James Angleton: The legendary chief of counterintelligence testified to Senate investigators behind closed doors in September 1975. The 155-page transcript of his comments is still secret in its entirety.

2. Birch O’Neal: Virtually unknown in the vast literature of JFK’s assassination, O’Neal played a key role in the CIA’s monitoring of Oswald. As an aide to Angleton, O’Neal ran a secretive office known as the Special Investigations Group, which opened the agency’s first file on Oswald in October 1959 (a story I tell in my new biography of Angleton, The Ghost).

Of the 224 pages in the O’Neal file released on November 3, 177 pages contain redactions, and three are wholly secret.

3. David Phillips: A decorated undercover officer, Phillips served as chief of Cuba operations in Mexico City in 1963. He supervised the surveillance of the Cuban Consulate in the Mexican capital, which Oswald visited six weeks before JFK was assassinated.

His personnel files containing 602 pages of material were released November 3, but 60 percent of those pages are fully or partially redacted. Only 227 pages are open to the public.

4. Ann Goodpasture: The senior woman in the Mexico City station in 1963, Goodpasture worked closely with Phillips and coordinated the station’s audio and photo surveillance operations during Oswald’s visit to Mexico City in September 1963.

Of 288 pages of material in the Goodpasture file, 95 pages (33 percent) contain some redactions, and 18 pages (6 percent) remain completely secret.

5. George Joannides: A psychological warfare operations officer who worked in Miami and New Orleans, Joannides handled the anti-Castro Cuban Student Directorate, which was funded by the CIA under the code name AMSPELL. Members of the group had a series of confrontations with Oswald in New Orleans in the summer of 1963.

The CIA has released 87 pages of AMSPELL documents, 72 of which are partly redacted. The only material made public was newspaper articles and brochures about the Cuban Student Directorate. None of the documents are dated before 1964.

The CIA told Trump that the JFK files could not be released because disclosure might endanger living CIA agents, an irrelevant objection in the case of these files. Angleton died in 1987, O’Neal died in 1995, Phillips died in 1988, Goodpasture died in 2011, and Joannides died in 1991.

What Have We Learned?

Judge John Tunheim, who oversaw the declassification of 4 million pages of JFK files in the 1990s, called the CIA withholding “disappointing.”

“They knew this deadline long ago,” Tunheim told Politico’s Bryan Bender. “It should have been done by Oct. 26, 2017.”

Dan Hardway, a West Virginia attorney and former investigator for the House Select Committee on Assassinations, notes that the CIA is not in compliance with the JFK Records Act, which requires federal agencies to provide a written explanation for withholding any files past October 26.

On the website of the Assassination Archives and Research Center in Washington, D.C., Hardway writes:

“There has been no explanation, let alone a presidential certification, that the massive redactions in these ‘released in full’ documents meet any of the mandatory exemptions that allow withholding. No identifiable harm is specified. No rationale is given as to why the secrets protected outweigh the public interest in disclosure. These files are not in compliance with the law no matter what the mainstream media says.”

Like Tunheim and Hardway, I doubt the CIA hiding “smoking gun” proof of a JFK conspiracy in these files. But after studying the JFK assassination for 25 years and James Angleton’s career for three, I believe there is smoking gun proof in the still-secret files about one of the CIA’s most sensitive secrets: that Lee Harvey Oswald was a CIA asset, witting or unwitting, who was used by Angleton and possibly others, for undisclosed intelligence purposes in the years, months and weeks before President Kennedy was gunned down.

Was the CIA’s monitoring and use of Oswald part of a conspiracy to kill the liberal president? There’s no definitive proof of that, but given the extraordinary secrecy still surrounding these records 54 years after the fact, it would be willfully naïve to rule out the possibility. Until all of the JFK files are released, the conspiracy question will be unresolved because of CIA secrecy.

Why it can make sense to believe in the kindness of strangers

(Credit: AP)

Would you risk your life for a total stranger?

While you might consider yourself incapable of acts of altruism on that scale, it happens again and again. During hurricanes and mass shootings, some people go to great lengths to help people they don’t even know while everyone else flees.

To learn whether this behavior comes more naturally to some of us than others, I partnered with Abigail Marsh and other neuroscientists working at the Laboratory on Social and Affective Neuroscience at Georgetown University. We studied the brains and behavior of some extraordinary altruists: people who have donated one of their own kidneys to a total stranger, known as nondirected donors.

Vox journalist Dylan Matthews explains in this video why he donated his left kidney to save a stranger’s life.

Unusually altruistic

These kidney donors may never learn anything about the recipient. That means they are not making this personal sacrifice because a relative or someone they may interact with in the future would benefit.

What’s more, this act of altruism is costly in multiple ways. It is a major, painful surgery. Many donors end up paying thousands of dollars out of pocket for medical and travel expenses, and they can lose out on salary and other earnings.

For the most part, there’s nothing to be gained in terms of the donor’s reputation. Many people, including some medical professionals, are skeptical about the motives of altruistic donors — even questioning their sanity.

These drawbacks help explain why altruistic kidney donation is extremely rare. Fewer than 2,000 people have done this to date in the United States since 1988, the first year with a recorded altruistic donor. That makes it something a mere one out of every 163,133 Americans have ever done.

And the norm is for living friends and family to donate kidneys to their loved ones. That was the case when celebrity Selena Gomez, who has lupus, got a new kidney from her best friend, the actress Francia Raisa.

Most commonly, the kidneys of deceased organ donors are used in transplants for strangers. There are about twice as many transplants from deceased donors as transplants from living ones.

Deceased donors and living friends and family account for a total of 99.5 percent of all kidney transplants performed over the past three decades.

Mammalian brains

Deep in the brains of all mammals — whether squirrel, bonobo or human — the same regions respond to distress and vulnerability. This response is especially common when babies cry out or appear threatened. In our most recent study, we investigated whether those brain systems, which are responsible for making all mammals care about helpless youngsters, play a key role in making some people extremely altruistic.

There are two major regions in what brain scientists call the “offspring care neural network,” evolutionarily old structures deep in the brain called the amygdala and the periaqueductal gray.

The amygdala is a small almond-shaped structure in both hemispheres tucked below the cortex. (Amygdala means almond in Greek.) One of its main roles in the brain is picking up on important emotional cues.

Research has long established that the amygdala is largely responsible for recognizing and feeling fear.

The periaqueductal gray is another small u-shaped structure at the base of the brain. It plays an important role in controlling basic behaviors like the impulse to cuddle a baby or the instinct to avoid predators.

Many studies have shown these structures and the connections between them are responsible for, say, motivating female rats to take care of their pups or making humans want to console crying babies.

Responding to distressed offspring is such a strong survival instinct that it can even cross species. A deer, for example, will respond when it hears a crying human infant.

Other research by Marsh’s lab has studied how people respond when they sense that others are afraid and feel an urge to comfort them.

The sight of frightened faces can evoke helping behavior. And people who are good at noticing that someone is afraid just by seeing their face tend to be more altruistic than the rest of us.

Scientists have long hypothesized that the care people extend to strangers may be a sort of extension of our most basic impulses to take care of our own kids. Scientists also believe that the ancient brain structures humans share with other mammals trigger these responses.

A test

To learn more about the brains of extremely altruistic people, we did an experiment with people who had donated one of their kidneys to someone they didn’t know. In our study, we asked these extreme altruists to read scenarios, some of which described people who were the target of harmful or callous behavior, and rate how much sympathy they felt. We did the same thing with a control group of people who had not donated a kidney.

Before reading some of these scenarios, we presented photos of fearful faces. These images were fleeting, lasting only 27 milliseconds. That means the participants couldn’t consciously recognize what they saw. Meanwhile, we scanned their brains.

We found some interesting effects while reviewing images captured during this experiment. Most notably, the amygdalas and their periaqueductal gray were more active for kidney donors than people in our control group, with stronger reactions to fearful and distressed stimuli.

What we found suggests that these two regions might be communicating or otherwise working together. We further tested this finding by looking at another aspect of our brain scans that allowed us to analyze how these two regions are connected by nerve cells.

My colleague Katherine O’Connell, a doctoral student, found that there seemed to be greater structural connections between these two regions too. These connections may help nerve impulses travel between them.

Understanding altruism

To be sure, more studies will have to be done to confirm our results before we can be sure how the offspring care neural network contributes to human altruism.

But our findings reinforce earlier neuroscience research that found that the amygdala and periaqeuductal gray, and communication between them, play an important role in caring for distressed and vulnerable others across all mammals — including humans.

These findings also build on our own prior research with altruistic kidney donors. In those earlier studies, we detected stronger amygdala responses when the donors glimpsed the faces of people who were feeling fear and that while altruistic kidney donors value friends and family as others do, they tend to be more generous toward strangers.

Our study of the brains of real-world altruists backs up these theories. Caring about someone you have never met, what we learned suggests, may have a lot in common with caring about the people you love.

Kristin Brethel-Haurwitz, Postdoctoral Researcher in Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Pennsylvania

Why Jenifer Lewis plays ABC’s “Black-ish” grandma Ruby with sass

(Credit: Peter Cooper)

“You know when I tackle those roles, I think of my mother and my aunts,” actor and singer Jenifer Lewis, who frequently plays mothers on screen, told me on “Salon Talks.”

Lewis’ many roles as a mother in film and television inspired the title of her new memoir, “The Mother of Black Hollywood.” She currently stars as Ruby Johnson, the grandmother on ABC’s “Black-ish.”

As a veteran black mother on and off screen, Lewis is able to bring an authenticity to her characters and shatter preconceived archetypes of what black motherhood often looks like in Hollywood. “I try to play them with yes, sass,” she said, and humor, “but I give them warmth; I give my characters warmth and heart.”

“Ruby loves her grand-babies, that’s what really grounds Ruby Johnson on ‘Black-ish,'” Lewis continued. “It’s a great environment, I’m happy there. I love my character, she gets to do so much: con-artist, shoot somebody, blow up a boat, lie to the kids. She’s very coo-coo, y’all.”

Most powerfully, she said, are the issues the show tackles head on, especially in today’s “dark times we’re having,” Lewis said. Growing up outside St. Louis herself, where teenager Mike Brown was gunned down by a police officer in 2014, Lewis has a message for police officers: “Stop shooting our children.”

Watch the video above for more of Lewis’ thoughts on police brutality and watch our full “Salon Talks” conversation on Facebook.

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

New healthy media habits for young kids

(Credit: Getty/dolgachov)

Who among us hasn’t fibbed when the doctor asks how much alcohol you drink? Who takes the suggested daily amount of Vitamin C? Who engages in moderate exercise precisely 150 minutes per week? Thought so. Turns out families treat their media diets the same way. Despite pediatricians’ ongoing recommendations to curb kids’ screen use, the “Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to Eight 2017” found that families with young kids are buying up mobile devices, using screens before bed, and streaming tons of video. But plenty of parents think their own kids’ media use is perfectly fine, and most believe that on the whole, it’s good for kids. So what does it mean when the reality doesn’t match the recommendations? It’s time for new rules.

Not no rules, just different ones — you may be OK for now, but studies show that media use steadily increases as kids get older, and there are risks to overexposure. Changing your approach to screen management before the tween and teen years will increase the chances that the stuff they’re interacting with is (mostly) good for them. It also allows you to think more deeply about how, when, and why you want your family to be using technology, so it enhances and enriches your lives.

Interestingly, the census found that even with all the new things kids are doing, their total daily amount of screen time hasn’t changed that much in six years. That’s good news because as long as you have basic limits, you can focus on choosing quality media and tech to make screen time really count. And with many parents reporting that media use benefits their kids’ learning and creativity, the new rules call for co-viewing and co-playing to boost those positive benefits (rather than screaming at your kids to turn off the computer).

Some parents ask: Why restrict media at all? Because honestly, nothing takes the place of the things that are proven to be best for little kids’ bodies and minds, like talking, playing, growing bored, and learning how to do stuff — especially in the crucial early years of a kid’s life. At the end of the day, it’s not your doctor you have to answer to — it’s your kids. Media and tech are and will continue to be huge in their lives. Start now to create a balanced approach that keeps everyone healthy.

5 Tips for Parents of Young Kids

Choose the good stuff (and not too much!). When your kids ask to see, play, or download something, don’t just take their word for it — check up on it. A lot of the age recommendations on media products are the creators’ best guess and aren’t necessarily a match for your child’s age and developmental stage. Read product reviews from independent sources (like Common Sense Media). Say no if you’re not comfortable with it. And when you approve something, help your kids enjoy it along with their other activities.

Don’t use screens right before bed, and keep them out of the bedroom overnight. Kids really need their sleep. Screens in the bedroom — especially in the hour before bedtime — interfere with the entire process of winding down, preparing for rest, and waking up refreshed and ready to tackle the day. If you’re unable to make the bedroom a screen-free zone (which is optimal but not always possible), keep TVs off for at least an hour before bedtime and set tablets or phones to night mode, turn off any notifications, and/or consider using Guided Access or another device setting to keep phones/tablets locked on a music or an alarm clock app.

Turn off the TV if no one is watching it. A lot of parents of young kids keep the TV on for company. But so-called background TV has been shown to get in the way of parents talking and interacting with their kids — which are key to helping kids learn language and communication. Background TV can also expose kids to age-inappropriate content. Seek out other forms of entertainment that you can listen to with your kid, such as music, kids’ podcasts, and audiobooks.

Make time for enjoying media with your kids, especially reading. Reading to your kid is one of the best things you can do — period. It’s great for bonding, but it also sets the stage for learning. While it’s nice to have a little library of books at home, you can read whatever’s available and it’ll be good for them. Product labels, signs, packaging copy — anything with words is fine. If you’re raising your kid in a place where you don’t completely know the language, feel free to read books or articles to them in your native tongue. Or just make up stories — it’s the rhythm, sounds, and communication that are important for kids to hear.

Practice what you preach. Remember, your kids are watching you. When your kids are little, create a family media plan to help you balance media and tech (theirs and yours) with all of the other things that are important to you. This isn’t just for them; it’s for you, too. Schedule in downtime, chores, homework, outdoor fun, reading, meals, etc. And then figure out how much extra is available for TV shows, games, apps and other media activities. Don’t worry about counting up daily screen time minutes — just aim for a balance throughout the week. Try to carve out times and locations that are “screen-free zones.” Hold yourself to them. Kids learn more from what we do than what we say, so make sure you’re role-modeling the right habits.

No hashtag without action: Why you should take your activism off-line

(Credit: Salon/Ilana Lidagoster)

“Yo, D, my Twitter was jumping. You see my threads, bro?” Joseph said. “It’s sooooo crazy how African-American brothers and amazing black sisters are treated in general, and this Trump stuff! It’s not right! I’m ready to flip out and attack a racist.”

Joseph is a nice guy. He cares about these issues, he wears graphic T-shirts with the names of civil rights movement leaders in bold font and uses every viral hashtag except #AllLivesMatter. Lately he’s been really into #ImWithKap. Like even when he posts something mundane like, “My eggs were decent this morning,” it has to end with #ImWithKap.

“I’m glad you are inspired,” I said. “But what do you actually do to help these situations?”

Joseph paused and thought for a second before he responded. You see, he’s a white guy. That doesn’t mean he can’t help — I have white friends who do amazing community work and really make a difference. I think his heart is in the right place, it’s just that he always tells me about Twitter and meet-ups and constantly repeats things that other activists have said. And then he’s always jumping from movement to movement without a clear focus or strategic plan that can lead to any positive result.

“I side with the people, man,” he responded, adjusting his glasses. “I make others aware of our privilege! And I fight against that!”

“But how or who do you actually fight other than other Facebook or Twitter account holders?” I asked. “You tell a white person to acknowledge their privilege and then what happens? Does it transfer to the nearest black guy? Can you denounce your privilege and advance me 65 privilege points so that I can activate them during routine traffic stops?”

We laughed.

“I need help when I do school visits sometimes, and my homie Dez feeds the homeless,” I said. “Can we call you?”

“For sure,” he said, slowly raising his black power fist. “Looking forward to chipping in.”

I wasn’t trying to attack Joseph. Like I said, he’s a nice guy. He’s just wasting his skills, time and energy by recycling the same language and actions as everyone else on the internet. He’s hashtagging without acting. Joseph is a great artist, and the world would benefit if he put his iPhone down for a while, stopped engaging rejects or following other worthless public activists and helped some kids develop a love for art. If he really wants to make a difference, that would be more effective.

And Joseph is not alone. I’m starting to become disenchanted with online activism because of the trash results. Don’t get me wrong — social media has been the single greatest tool for starting and connecting movements and raising awareness; however, it’s created a ton of pseudo-leaders who play revolutionary without any experience in organizing, grassroots work or human relationships in general. Their only talent is social media, so they rack up huge followings and spread weak ideas that never work. The end result is Facebook and Twitter feeds are full of people who think simply acknowledging white privilege elevates people of color, that hating men makes you a better feminist and recycling the borrowed ideas of a digital revolutionary makes you a change maker.

Stop it. Go out into the world and spread real love, because 20 years later we’ll all be in our 40s and 50s and if activism remains the same, nothing will be different except the new hashtags created for the new victims.

“We don’t negotiate with terrorists” and other myths you were taught

Oliver North; Ronald Reagan (Credit: Getty/Chris Wilkins/AP/Photo montage by Salon)

1. Indulging Terrorists: The United States will never negotiate with terrorists, never ransom political prisoners, nor make concessions to insurgents.

Don’t you believe it.

The U.S. government has a firm policy never to deal with terrorists—never ever. Until, that is, a deal is made.

One particularly notorious exception occurred in 1986, when President Reagan facilitated the sale of arms to Iran—though an embargo on such sale was in force—and used that income to finance the Contras opposing the communist Sandinista government of Nicaragua—which was also illegal, and specifically forbidden by Congress. But President Reagan considered the Contras to be “the moral equivalent of our founding fathers,” even though they had a long history of disregard for human rights.

The episode became known as the “Iran-Contra affair,” the arms transfer to Iran intended as a quid pro quo for the release of hostages held in Lebanon by a group tied to the Iranis. The Contras were not an intact force, but a cluster of several right-of-center Nicaraguan groups allied only in their opposition to the left-wing government. A report commissioned by the State Department found Reagan’s assertion of Soviet influence in Nicaragua to be “exaggerated.” The two activities were independent covert operations, related only by propinquity.

The International Court of Justice found that the US had violated international law by supporting the Contras, by mining Nicaragua’s harbors, and by encouraging violation of humanitarian law in its publication and distribution of the manual Psychological Operations in Guerilla Warfare. The manual, among other things, rationalized killing civilians.

It was a complex arrangement, both supporting and opposing insurgencies. Both, however, contrary to explicit US policy.

2. United Nations Location: The property in New York City on which the United Nations is built was donated to the UN by John D. Rockefeller as an expression of his philanthropic largess.

Don’t you believe it.

There may have been an altruistic component to Rockefeller’s benevolence, but his proposal to donate the land was more a business decision.

The seventeen acres on which the UN complex was constructed had previously been an area of slaughterhouses and a railroad garage, all accumulated by land developer named William Zeckendorf, one of Rockefeller’s most zealous competitors. Zeckendorf had purchased the land with the intention of constructing a city-within-a-city to rival Rockefeller Center, a district for business, tourism, and cultural activity, a “dream city” with its own transportation system and distinctive design. His plan called for a multimillion-dollar complex of several office buildings, hotels, and apartment houses, supported by theaters, shopping areas, a marina, and, of course, a rooftop airport. He anticipated a major impact on New York City with the relocation and absorption of the Metropolitan Opera and a floating restaurant/nightclub. Such a zone would surely diminish the distinctive allurement of Rockefeller Center as a place to visit and do business in.

But like many of Zeckendorf’s expansive schemes, his financing didn’t keep pace with his implementation and he soon developed money problems. Which gave Rockefeller the opportunity to advance his reputation for civic responsibility while at the same time eliminating likely business competition. Nelson, John D.’s son, managed to buy the seventeen acres for $8.5 million and the senior Rockefeller donated it to the UN, for which he took on a whole new reserve of renown as the American who gave the United Nations its home.

3. The Death of Diana: Princess Diana died in an auto crash, caused by overzealous paparazzi trailing hers in other vehicles.

Don’t you believe it.

In July 1981, Lady Diana Spencer wed Prince Charles, heir to the throne of England. Affectionately known as Princess Di, she became the darling of the English people: she was young, attractive, and brought vitality to the otherwise stodgy British royal family. The marriage was not happy but it produced two sons and was maintained for propriety’s sake. Meanwhile, Diana had a five-year affair beginning in 1986 with her sons’ riding instructor, Major James Hewitt. She and Charles separated in December 1992, and divorced in August 1996.

Following her divorce, Diana retained a high level of popularity. She devoted herself to her sons and to her charitable endeavors, staying in the public eye through reports of her relationships with several men. But in 1997, she found the man she considered her true love—playboy Dodi Fayed, owner of Harrods Department Store in London. On holiday in Paris, just after midnight on August 31, 1997, Diana and Dodi left the Ritz Hotel in a black Mercedes followed by a clutch of photographers. Driver Henri Paul was able to outrun most of them, but in an underpass at the Pont de l’Alma, driving over 100 miles per hour, he crashed into a concrete post, killing himself and Dodi and sending Diana to the hospital in critical condition, where she later died.

A French investigation concluded that the paparazzi were distant from the Mercedes and were not responsible, but “the driver of the car was inebriated . . . not in a position to maintain control of the vehicle.” A British inquest also attributed the accident to gross negligence by driver Henri Paul, who was found to have a blood alcohol level three times the legal limit. The paparazzi were exonerated.

4. Hamilton and Burr: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, who faced off against each other in what was probably the most famous duel in American history, were lifelong adversaries.

Don’t you believe it.

Hamilton and Burr were both lawyers, frequently on opposite sides in legal actions. They were also political opponents. Hamilton is quoted as observing that they “had always been opposed on politics but always in good terms.” Others in their circle did not see them as quite so conciliatory. But there was one trial that had them working together as co-counsels.

It is remembered as the Manhattan Well Murder case of 1800 in New York; incidentally it is the first murder trial in the United States for which a recorded transcript exists. A young man named Levi Weeks was accused of killing Gulielma Sands, a young woman he had been dating. She disappeared on December 22, 1799; her body was found in a nearby well, from which it was recovered eleven days later. Before leaving her boarding house on the night she disappeared, Gulielma had told her cousin she was planning to elope with Levi Weeks that evening.

Through his influential brother’s connections, Weeks retained Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, two prominent attorneys, to defend him. Ezra Weeks was a wealthy contractor who had Burr and Hamilton as clients. Both were in debt to Ezra and he called in those favors. But Hamilton and Burr were commercial lawyers, neither having had much contact with murder cases before, so they took on a third attorney, an experienced criminal lawyer named Henry Brockholst Livingston. The trial lasted two days, the jury’s deliberation only five minutes to acquit Weeks.

So at least on one occasion Hamilton and Burr had worked together as co-counsels on the same side only four years before their historic duel.

5. Foreign Aid: The United States’ moral and humanitarian leadership of the world is shown by our supremacy among the world’s nations in providing foreign aid to those nations that most need it.

Don’t you believe it.

In 2014, the latest year for which data is available at the time of this writing, the United States donated the most foreign aid of all countries, $32 billion. But that figure is not so impressive when viewed as a percentage of the gross national income (GNI); it is only 0.19 percent, the same as Portugal and Japan. Several other countries contributed a much higher share.

A target of 0.7 percent of GNI had been established as an official development assistance (ODA) by the UN in 1970, that level of ODA/GNI accepted by the twenty-nine members that later signed on to the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC). The EU members that were in the DAC agreed to reach the target by 2015. By 2014, five had succeeded. Sweden led the pack, donating 1.1 percent of its GNI to foreign aid. Luxembourg donated 1.07 percent, Norway 0.99 percent, Denmark 0.85 percent, and the UK 0.71 percent. Among those countries that didn’t make the target were Germany at 0.41 percent, France at 0.36 percent, and Switzerland at 0.49 percent, all still significantly more than the US.

But the country that donated the most to foreign aid, measured as a percentage of GNI, was the United Arab Emirates (not in the DAC), which contributed an impressive 1.17 percent.

The picture changes if we include nongovernmental aid. The Hudson Institute, a private think tank, estimates private assistance for 2014 at $71.2 billion. That figure, though, is in dispute by some authorities because it includes $47 billion in foreign individuals’ remittances to family members. Excluding that item, private aid comes to $24 billion. Added to governmental foreign aid, that brings the sum of US foreign aid to $56 billion, or 0.34 percent, still not even in the top ten.

Andy Warhol, record producer: capturing the sonic attack of The Velvet Underground

(Credit: Wikipedia/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon)

In hands-on terms [John] Cale has said, “Andy Warhol didn’t do anything.” Warhol’s unique style might disqualify him from the title of “producer” at all, making him effectively an executive producer. But Warhol’s role, and his effect as producer cannot be denied. You could say he produced the producers as well as the band. Longtime friend of the band, rock manager and A&R legend Danny Fields spoke eloquently on the subject in “Uptight: The Velvet Underground Story”:

Andy doesn’t know how to translate ideas into musical terms . . . Andy . . . was making them sound like he knew they sounded at the Factory. That’s what I would do if I were an amateur at production . . . What Andy did was very generously reproduce . . . the way it sounded to him when he first fell in love with it.

The group had their sound together before meeting Warhol. They had Lou Reed’s experience at Pickwick [Records] to prepare them for the studio’s technical challenges, and the good fortune to luck into [Norman] Dolph and [John] Licata at the right moment. In Los Angeles fortune smiled again, and they added Tom Wilson’s expertise as well. So there was no need at all for Warhol to be a knob twiddler—which he clearly wasn’t.

Reed: Andy was the producer and Andy was in fact behind the board gazing with rapt fascination . . .

Cale: . . . at all the blinking lights.

Reed: . . . At all the blinking lights. He just made it possible for us to be ourselves and go right ahead with it because he was Andy Warhol. In a sense he really did produce it, because he was this umbrella that absorbed all the attacks when we weren’t large enough to be attacked . . . as a consequence of him being the producer, we’d just walk in and set up and do what we always did and no one would stop it because Andy was the producer. Of course he didn’t know anything about record production—but he didn’t have to. He just sat there and said “Oooh, that’s fantastic,” and the engineer would say, “Oh yeah! Right! It is fantastic, isn’t it?”

This alone made Warhol indispensable to the album. But, of course, he did more than that. Fricke calls Warhol “a specialist in subtly engineered collisions of people and ideas,’ and in that role Warhol (with help from Paul Morrissey) coaxed the group into accepting Nico as a vocalist, completing the chemistry that makes the album so amazing. He was also the umbrella under which Dolph in New York and Wilson in LA (and later New York) worked, unfettered by label interference. And he got the album heard, for even if Dolph and Wilson had done brilliant work, without the carte blanche Warhol provided it’s doubtful the recording would have made it onto vinyl. Thus, Warhol did precisely what a great producer should: he achieved an effective translation of the sound that the band heard in their heads on to tape, and then he got it out into the world in tact.

A trade-off of Warhol’s inexperience in the studio could have been a disastrous loss in Sonic clarity. Cale also claimed that Norman Dolph “didn’t understand the first f**king thing about recording . . . he didn’t know what the hell he had on his hands,’ and while Dolph didn’t dispute the charges (he responds “nobody knew what they were doing”), I think Cale’s criticism is way off the mark. First of all, with Cale filling the role of creative producer without portfolio, Dolph says:

I never felt I had the authority to pick takes, or veto them—that, to me, was clearly up to Cale, Reed and Morrison . . . Lou Reed was more the one who’d say “this needs to be a little hotter,” he made decisions about technical things . . . and the mixing was really between Cale, Sterling and John Licata, ’cause that was all, again, done in real time.

As for sound quality, over-saturated tapes caused some audible distortion, and noise from less-than-perfect overdubs is also in evidence. But considering the unprecedented Sonic attack in songs like “European Son” and “Black Angel’s Death Song,” which few engineers would have been comfortable capturing (or tolerating) in 1966, you have to agree that the Dolph-Licata team performed brilliantly. Any doubts on that score can be dispelled with a few “this is what might have been” moments of comparative listening to Reed’s primitive-sounding Pickwick recordings, which aren’t even in the same ballpark as Licata’s engineering work. And any noise/distortion issues on the LP detract little from the overall listening experience. Moreover, the band happily accepted these slight technical shortfalls at the time, and-whether by their own design or Warhol’s—band and producer shared an aesthetic that made errors part of the modus operandi. Reed noted:

No one wants it to sound professional. It’s so much nicer to play into one very cheap mike. That’s the way it sounds when you hear it live and that’s the way it should sound on the record.

Warhol elaborated:

I was worried that it would all come out sounding too professional . . . one of the things that was so great about them was they always sounded so raw and crude. Raw and crude was the way I liked our movies to look, and there’s a similarity between sound in that album and the texture of “Chelsea Girls,” which came out at the same time.

The studio approach they took, as recalled by Dolph, left little threat of things sounding too professional:

From a take-wise point of view you weren’t presented with many options. They either got it right, or broke down, or did a couple of takes; but it wasn’t as though you got 17 takes . . . either you chose this one or you chose that one and then you went on and did the next one. Usually they’d do a piece of one and then come in and listen to it. If one got largely through and it broke down, they’d come in and listen to it and say “yeah that sounds like we got it right”; or, if one got all the way through, they’d come in and either buy it, or adjust the mix or do it again. But there were not a whole lot of complete takes.

The strange story of turkey tails speaks volumes about our globalized food system

(Credit: AP Photo/Danny Johnston, File)

Intensive livestock farming is a huge global industry that serves up millions of tons of beef, pork and poultry every year. When I asked one producer recently to name something his industry thinks about that consumers don’t, he replied, “Beaks and butts.” This was his shorthand for animal parts that consumers — especially in wealthy nations — don’t choose to eat.

On Thanksgiving, turkeys will adorn close to 90 percent of U.S. dinner tables. But one part of the bird never makes it to the groaning board, or even to the giblet bag: the tail. The fate of this fatty chunk of meat shows us the bizarre inner workings of our global food system, where eating more of one food produces less-desirable cuts and parts. This then creates demand elsewhere — so successfully in some instances that the foreign part becomes, over time, a national delicacy.

Spare parts

Industrial-scale livestock production evolved after Word War II, supported by scientific advances such as antibiotics, growth hormones and, in the case of the turkey, artificial insemination. (The bigger the tom, the harder it is for him to do what he’s supposed to do: procreate.)

U.S. commercial turkey production increased from 16 million pounds in January 1960 to 500 million pounds in January 2017. Total production this year is projected at 245 million birds.

That includes a quarter-billion turkey tails, also known as the parson’s nose, pope’s nose or sultan’s nose. The tail is actually a gland that attaches the turkey’s feathers to its body. It is filled with oil that the bird uses to preen itself, so about 75 percent of its calories come from fat.

It’s not clear why turkeys arrive at U.S. stores tailless. Industry insiders have suggested to me that it may simply have been an economic decision. Turkey consumption was a novelty for most consumers before World War II, so few developed a taste for the tail, although the curious can find recipes online. Turkeys have become larger, averaging around 30 pounds today compared to 13 pounds in the 1930s. We’ve also been breeding for breast size, due to the American love affair with white meat: One prized early big-breasted variety was call Bronze Mae West. Yet the tail remains.

Savored in Samoa

Rather than letting turkey tails go to waste, the poultry industry saw a business opportunity. The target: Pacific Island communities, where animal protein was scarce. In the 1950s U.S. poultry firms began dumping turkey tails, along with chicken backs, into markets in Samoa. (Not to be outdone, New Zealand and Australia exported “mutton flaps,” also known as sheep bellies, to the Pacific Islands.) With this strategy, the turkey industry turned waste into gold.

By 2007 the average Samoan was consuming more than 44 pounds of turkey tails every year – a food that had been unknown there less than a century earlier. That’s nearly triple Americans’ annual per capita turkey consumption.

When I interviewed Samoans recently for my book “No One Eats Alone: Food as a Social Enterprise,” it was immediately clear that some considered this once-foreign food part of their island’s national cuisine. When I asked them to list popular “Samoan foods,” multiple people mentioned turkey tails — frequently washed down with a cold Budweiser.

How did imported turkey tails become a favorite among Samoa’s working class? Here lies a lesson for health educators: The tastes of iconic foods cannot be separated from the environments in which they are eaten. The more convivial the atmosphere, the more likely people will be to have positive associations with the food.

Food companies have known this for generations. It’s why Coca-Cola has been ubiquitous in baseball parks for more than a century, and why many McDonald’s have PlayPlaces. It also explains our attachment to turkey and other classics at Thanksgiving. The holidays can be stressful, but they also are a lot of fun.

As Julia, a 20-something Samoan, explained to me, “You have to understand that we eat turkey tails at home with family. It’s a social food, not something you’ll eat when you’re alone.”

Turkey tails also come up in discussions of the health epidemic gripping these islands. American Samoa has an obesity rate of 75 percent. Samoan officials grew so concerned that they banned turkey tail imports in 2007.

But asking Samoans to abandon this cherished food overlooked its deep social attachments. Moreover, under World Trade Organization rules, countries and territories generally cannot unilaterally ban the import of commodities unless there are proven public health reasons for doing so. Samoa was forced to lift its ban in 2013 as a condition of joining the WTO, notwithstanding its health worries.

Author Michael Carolan cooks turkey tails for the first time.

Embracing the whole animal

If Americans were more interested in eating turkey tails, some of our supply might stay at home. Can we bring back so called nose-to-tail animal consumption? This trend has gaining some ground in the United States, but mainly in a narrow foodie niche.

Beyond Americans’ general squeamishness toward offal and tails, we have a knowledge problem. Who even knows how to carve a turkey anymore? Challenging diners to select, prepare and eat whole animals is a pretty big ask.

Google’s digitization of old cookbooks shows us that it wasn’t always so. “The American Home Cook Book,” published in 1864, instructs readers when choosing lamb to “observe the neck vein in the fore quarter, which should be of an azure-blue to denote quality and sweetness.” Or when selecting venison, “pass a knife along the bones of the haunches of the shoulders; if it smell [sic] sweet, the meat is new and good; if tainted, the fleshy parts of the side will look discolored, and the darker in proportion to its staleness.” Clearly, our ancestors knew food very differently than we do today.

It is not that we don’t know how to judge quality anymore. But the yardstick we use is calibrated — intentionally, as I’ve learned — against a different standard. The modern industrial food system has trained consumers to prioritize quantity and convenience, and to judge freshness based on sell-by-date stickers. Food that is processed and sold in convenient portions takes a lot of the thinking process out of eating.

If this picture is bothersome, think about taking steps to recalibrate that yardstick. Maybe add a few heirloom ingredients to beloved holiday dishes and talk about what makes them special, perhaps while showing the kids how to judge a fruit or vegetable’s ripeness. Or even roast some turkey tails.

If this picture is bothersome, think about taking steps to recalibrate that yardstick. Maybe add a few heirloom ingredients to beloved holiday dishes and talk about what makes them special, perhaps while showing the kids how to judge a fruit or vegetable’s ripeness. Or even roast some turkey tails.

Michael Carolan, Professor of Sociology and Associate Dean for Research, College of Liberal Arts, Colorado State University