Lily Salter's Blog, page 226

November 28, 2017

These memes riffing on Melania Trump’s creepy Christmas videos are early stocking stuffers

Melania Trump walks through Christmas decorations in the East Wing at the White House (Credit: Getty/Saul Loeb)

Ho, ho, ho. The Holidays are upon us, and our first gift of the season has arrived: An internet chock full of dank, dank Melania memes.

If you haven’t yet seen, Christmas celebrations have already kicked off on the White House’s social feeds with a catalog the First Lady Melania Trump’s efforts to bring seasonal cheer to the loneliest place on earth, one that was met on Twitter with an outcry of confusion, laughter and memes on memes on memes.

First, there was this somewhat disturbing video of First Lady Melania Trump watching a ballet performance, stone-faced and distant as she stared past the dancers and, perhaps, into the abyss that is her cloistered existence. The resulting memes were tight.

MELANIA: “What is it like for your body to be free?” https://t.co/F50fo4kGih

— Jess Dweck (@TheDweck) November 27, 2017

Melania looks like she just stumbled into the middle of all of this on her way to get a glass of water and now she doesn’t know if it’s weirder if she stays or if she leaves. https://t.co/yrCd5PSPxA —

Salon’s founder David Talbot recovering from stroke

David Talbot (Credit: HarperCollins)

On November 18, prominent progressive journalist and founder of Salon David Talbot suffered a stroke. Talbot’s family says that his prognosis is good, but he faces months of physical rehabilitation before he can get back to work. To that end, Talbot’s family and friends are raising $65,000 to help offset costs while he recovers.

Talbot most recently worked as a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle. A former senior editor for Mother Jones, he’s the author of several nonfiction books, including the New York Times bestseller “Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years” and 2015’s “The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government.” In addition to founding Salon in 1995, Talbot served as as editor in chief and CEO until 2005 (and again as CEO in 2011).

The Salon family wishes Talbot a swift and full recovery. Here’s what his family wrote on the fundraising page:

David Talbot is one of progressive journalism’s most tireless and impassioned voices. For decades now, he has been holding American power accountable as well as fighting for those who are suffering its effects – through his books, journalism, and community activism. Now he needs our help.

On November 18, David’s work was interrupted when he suffered a stroke. His prospects for recovery are excellent — his cognitive abilities are completely intact. But he has motor deficits that will require months of intense physical rehabilitation before he can work again. Like most writers, his income is dependent on writing, and he won’t be able to write for a while. His wife, Camille, who is also a writer, will need to devote much of her time to his care.

David has devoted his life to bringing to light a hidden history of American iniquity, and the critics, dreamers and rebels who fought against it. Before his stroke, he was working on a new book that extolls courageous leadership in the face of darkness. We appreciate any gift you are able to give as David faces his own dark personal time. With your help and good wishes, we know he will recover and continue to fight the good fight.

You can donate to Talbot’s recovery fund through GoFundMe.

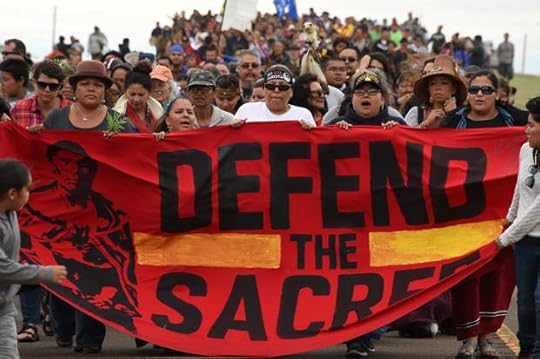

DAPL contractors paid a firm to build a conspiracy lawsuit against protestors

(Credit: Getty/Robyn Beck)

Security firm TigerSwan was paid to build a conspiracy lawsuit against DAPL protesters. Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the Dakota Access Pipeline, brought on the paramilitary outfit to surveil pipeline opponents with the intent of mounting a racketeering case against Greenpeace and other activist organizations, say three former TigerSwan contractors who spoke to The Intercept.

The lawsuit alleges that environmental groups engineered the #noDAPL movement in order to garner donations by paying protestors and inciting them to commit criminal activity and domestic terrorism.

Greenpeace general counsel Tom Wetterer told The Intercept that the lawsuit “grossly distorts the law and facts at Standing Rock.” While he’s certain Energy Transfer Partners won’t win, he notes that “what they’re really trying to do is silence future protests.”

Earlier this year, Grist and the Intercept independently reported on leaked TigerSwan documents that revealed its targeting of activists as jihadists in an intrusive military-style surveillance campaign. Within a month, a North Dakota state agency filed a complaint against the firm for operating there without a license. And Louisiana later denied TigerSwan permission to work there.

A lawyer representing DAPL opponents suing law enforcement, alleging police brutality and civil rights violations, told the Associated Press that online reports about TigerSwan’s operations are only strengthening her clients’ case.

This Native American tribe owns one of the world’s most valuable patents

(Credit: AP Photo/Chris Post)

Allergan, the drugmaker behind Botox, is using an unprecedented tactic to protect its valuable patents – angering lawyers and politicians, and keeping the price of its medicines high.

There has long been a debate about patents and traditional knowledge in developing countries. Pharmaceutical companies in the West, like Allergan, are often accused of “bio-prospecting.” They collect raw samples of traditional medicines and plants, whose healing properties have been known to locals for centuries, and patent modified extracts of the active ingredients. (Under patent law, existing natural materials such as plants and trees cannot be patented as they are not “novel”.)

Under international treaties, such as the Convention on Biodiversity, companies need to ask permission before bio-prospecting. However, under patent law, pharmaceutical companies don’t have to share revenues from drugs developed in part from the exploitation of indigenous traditional knowledge. To add insult to injury, the patented medicines are often too costly for people in developing countries to afford.

Bizarre twist

The debate over patents and the rights of indigenous peoples has taken a bizarre new twist in recent months. Allergan transferred the ownership of the patents on one of its most valuable medicines – Restasis, a treatment for chronic dry eyes that had US$1.5 billion in sales in 2016 alone – to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe of New York State. It now plans to lease back the rights to the drug.

This may seem like a case of the pharmaceutical industry seeking to right historical wrongs by giving something back to an indigenous group that has long suffered from discrimination and dispossession – but it is not. The deal is purely a self-interested one on the part of Allergan. But there is no doubt that, in an inversion of the classic debate about using patents to exploit the knowledge of indigenous peoples, the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe will also benefit from the deal.

So how did this come about? US law grants Native American tribes “sovereign immunity” in relation to their reservations, shielding them from some US federal laws. Since 2012 there has also been a system of challenging patents at the US Patents and Trademarks Office (USPTO) known as “Inter-partes Review”. This allows competitors to argue at USPTO panels that a granted patent ought to be invalidated. It is quicker and more cost-effective than challenging a patent in court.

This new system has invalidated many pharmaceutical patents. By transferring their patents to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and leasing them back from the tribe for an annual fee of up to US$15m, Allergan is effectively paying the tribe to take advantage of its sovereign immunity, which also shields the patents from challenge. If this unprecedented legal strategy succeeds, it could prolong Allergan’s monopoly and stifle generic competition.

Meanwhile, the tribe, as quoted in the Allergan press release, said it viewed the deal as a way to benefit from the patent system, and that it would use the money for good causes in the community.

Unsurprisingly, there has been a great deal of opposition to this tactic. Shortly after the deal was announced in September 2017, several US senators asked the senate judiciary committee Allergan’s alleged “anti-competitive attempt to shield its patents from review and keep drug prices high”.

There is also an ongoing court challenge that may yet lead to a ruling that this strategy is an abuse of the sovereign immunity process. Yet if the Allergan-Saint Regis agreement survives legal challenge it will encourage further deals between US Native American tribes and pharmaceutical companies.

Ingenious tactic

There’s no doubt that the legal tactic is an ingenious one. Yet, even if we consider it a good thing that the tribe has found a new source of revenue, the deal should give us all pause for thought.

In addition to the competition concerns, this tactic subverts the protection given to Native American tribes under US law, in part to account for their historical dispossession. In other words, it uses the tribe’s status to boost corporate power and control of patented medicines.

It also, of course, does nothing to help other indigenous groups around the world, particularly those in developing countries. Although it turns the classic debate over patents and indigenous peoples on its head, the deal may end up doing more harm than good.

It also, of course, does nothing to help other indigenous groups around the world, particularly those in developing countries. Although it turns the classic debate over patents and indigenous peoples on its head, the deal may end up doing more harm than good.

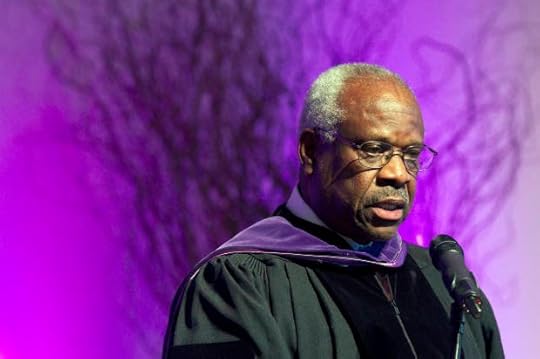

Clarence Thomas must resign

(Credit: AP)

Utah Republican Orrin Hatch called “bullcrap” on Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown last week. The Senate Finance Committee lion tore into Brown for “spewing” that the Republican tax plan to transfer a trillion dollars to the rich was in reality a Republican tax plan to transfer a trillion dollars to the rich.

I got my first dose of Hatch during the wall-to-wall coverage of the confirmation of Clarence Thomas, George H.W. Bush’s Supreme Court nominee. Hatch was the Republicans’ designated questioner of Anita Hill. She was called to testify because she’d told the FBI that Thomas had sexually harassed her ten years earlier, when he was her boss at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Education.

Sitting behind her were her mother, Erma (“who is going to be celebrating her 80th birthday”); her father, Albert; her sisters, Elreathea, Jo Ann, Coleen and Joyce; and her brother, Ray. No way she was going to lie to the committee, or to us, in front of them.

Hill testified that Thomas had repeatedly asked her out, and that she repeatedly refused. So he demeaned her. He told her someone had once “put a pubic hair” on his Coke can. He said porn star Long Dong Silver had nothing on him in the endowment department.

Hatch called her charges “contrived” and “sick.” He claimed she’d stolen them. The pubic hair, she’d taken from page 70 of “The Exorcist.” Long Dong Silver, she’d lifted from a Kansas sexual harassment case.

Hill agreed to a polygraph test, and passed. Thomas refused. He called the hearings a “high-tech lynching for uppity blacks.”

It was painful to watch Hatch slime Hill. Women who’d also been sexually harassed found in the hearings no reason to be less fearful of telling their stories. Nor, later, could they take comfort in how Bill Clinton’s accusers were reviled. Or Bill O’Reilly’s. Or Roger Ailes’s.

But something changed. The tipping point may have been Donald Trump bragging to Billy Bush about assaulting women. Sixteen of his victims had the courage to say he’d harassed or groped them.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Trump’s escape from accountability for that predation contributed to the decisions by Harvey Weinstein’s victims to talk on the record to Jodi Kantor and her New York Times colleagues and to Ronan Farrow at the New Yorker. Before long, more than 80 women attested to Weinstein’s assaults as far back as 1990.

Then nine women gave the Washington Post detailed accounts of Alabama Republican senatorial candidate Roy Moore’s history of pedophilia and abuse. They knew the blowback would be brutal. They did it anyway.

Still, Moore won’t quit. Why would he? Kay Ivey, Alabama’s Republican governor, says she’ll vote for him even though she believes his accusers. Better to elect a pedophile than a Democrat who’d vote against a Supreme Court nominee who’d overturn Roe v Wade.

Now Senator Al Franken is in the crosshairs. The Minnesota Democrat offered an apology to Leann Tweeden for “completely inappropriate” behavior in 2006, which she accepted, and he asked for an ethics investigation of the incident. Calls for his resignation illustrate the fallacy of false equivalence; they’re the witch-hunt Trump claimed had victimized him.

Hill was a thoroughly credible witness. Thomas has no stronger case for his innocence than do Trump, Moore or Weinstein. Pressed to defend Trump’s sexual improprieties, his press secretary said the American people “spoke very loud and clear when they elected this president.” No to put too fine a point on it, but she’s spewing bullcrap. Elections don’t decide culpability.

In the wake of the Hill/Thomas hearings, a record-breaking 117 women made it onto the federal ticket in the 1992 election. The 24 women elected to the House that year was the largest number in any single House election, and the three elected to the Senate tripled the number of women senators.

That sharp uptick didn’t persist. If you think that today’s 80% male Congress isn’t good enough, check out Project 100, which is working to elect 100 progressive women to Congress by 2020, the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote. Full disclosure: my daughter is a co-founder. As her dad, and as the onetime speechwriter for the first presidential candidate to pick a woman as his running mate, you can imagine how proud of her I am. And how hopeful she and her young teammates make me feel.

# # #

Marty Kaplan is the Norman Lear professor of entertainment, media and society at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

November 27, 2017

The secret to turtle hibernation: butt-breathing

Loggerhead sea turtle hatchlings swim in a tank at the Gumbo Limbo Nature Center before being taken to a U.S. Coast Guard vessel for release, Monday, July 27, 2015, in Boca Raton, Fla. More than 600 Loggerhead hatchlings, nine Green sea turtle hatchlings, three rehabilitated Loggerhead post-hatchling and one Hawksbill post-hatchling sea turtle were released onto free-floating sargassum seaweed offshore. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee) (Credit: AP)

To breathe or not to breathe, that is the question.

What would happen if you were submerged in a pond where the water temperature hovered just above freezing and the surface was capped by a lid of ice for 100 days?

Well, obviously you’d die.

And that’s because you’re not as cool as a turtle. And by cool I don’t just mean amazing, I mean literally cool, as in cold. Plus, you can’t breathe through your butt.

But turtles can, which is just one of the many reasons that turtles are truly awesome.

Cold weather slow down

As an ectotherm — an animal that relies on an external source of heat — a turtle’s body temperature tracks that of its environment. If the pond water is 1℃, so is the turtle’s body.

But turtles have lungs and they breathe air. So, how is it possible for them to survive in a frigid pond with a lid of ice that prevents them from coming up for air? The answer lies in the relationship between body temperature and metabolism.

A cold turtle in cold water has a slow metabolism. The colder it gets, the slower its metabolism, which translates into lower energy and oxygen demands.

When turtles hibernate, they rely on stored energy and uptake oxygen from the pond water by moving it across body surfaces that are flush with blood vessels. In this way, they can get enough oxygen to support their minimal needs without using their lungs. Turtles have one area that is especially well vascularized — their butts.

See, I wasn’t kidding, turtles really can breathe through their butts. (The technical term is cloacal respiration.)

Not frozen, just cold

We are not turtles. We are endotherms — expensive metabolic heat furnaces — that need to constantly fuel our bodies with food to generate body heat and maintain a constant temperature to stay alive and well.

When it’s cold out, we pile on clothes to trap metabolic heat and stay warm. We could never pick up enough oxygen across our vascularized surfaces, other than our lungs, to supply the high demand of our metabolic furnaces.

For humans, a change in body temperature is a sign of illness, that something is wrong. When a turtle’s body temperature changes, it’s simply because the environment has become warmer or colder.

But even ectotherms have their limits. With very few exceptions (e.g., box turtles), adult turtles cannot survive freezing temperatures; they cannot survive having ice crystals in their bodies. This is why freshwater turtles hibernate in water, where their body temperatures remain relatively stable and will not go below freezing.

Water acts as a temperature buffer; it has a high specific heat, which means it takes a lot of energy to change water temperature. Pond water temperatures remain quite stable over the winter and an ectotherm sitting in that water will have a similarly stable body temperature. Air, on the other hand, has a low specific heat so its temperature fluctuates, and gets too cold for turtle survival.

Crampy muscles

An ice-covered pond presents two problems for turtles: they can’t surface to take a breath, and little new oxygen gets into the water. On top of that, there are other critters in the pond consuming the oxygen that was produced by aquatic plants during the summer.

Over the winter, as the oxygen is used up, the pond becomes hypoxic (low oxygen content) or anoxic (depleted of oxygen). Some turtles can handle water with low oxygen content — others cannot.

Snapping turtles and painted turtles tolerate this stressful situation by switching their metabolism to one that doesn’t require oxygen. This ability is amazing, but can be dangerous, even lethal, if it goes on for too long, because acids build up in their tissues as a result of this metabolic switch.

But how long is “too long”? Both snapping turtles and painted turtles can survive forced submergence at cold water temperatures in the lab for well over 100 days. Painted turtles are the kings of anoxia-tolerance. They mobilize calcium from their shells to neutralize the acid, in much the same way we take calcium-containing antacids for heartburn.

In the spring, when anaerobic turtles emerge from hibernation, they are basically one big muscle cramp. It’s like when you go for a hard run — your body switches to anaerobic metabolism, lactic acid builds up and you get a cramp. The turtles are desperate to bask in the sun to increase their body temperature, to fire up their metabolism and eliminate these acidic by-products.

And it’s hard to move when they’re that crampy, making them vulnerable to predators and other hazards. Spring emergence can be a dangerous time for these lethargic turtles.

Cold weather turtle tracking

Field biologists tend to do their research during the spring and summer, when animals are most active. But in Ontario, where the winters are long, many turtle species are inactive for half of their lives.

Understanding what they do and need during winter is essential to their conservation and habitat protection, especially given that two-thirds of turtle species are at risk of extinction.

My research group has monitored several species of freshwater turtles during their hibernation. We attach tiny devices to the turtles’ shells that measure temperature and allow us to follow them under the ice.

We’ve found that all species choose to hibernate in wetland locations that hover just above freezing, that they move around under the ice, hibernate in groups and return to the same places winter after winter.

Despite all this work, we still know so little about this part of turtles’ lives.

So, I do what any committed biologist would do: I send my students out to do field research at -25℃. We are not restricted to fair-weather biology here.

Besides, there is unparalleled beauty in a Canadian winter landscape, especially when you envision all of those awesome turtles beneath the ice, breathing through their butts.

Besides, there is unparalleled beauty in a Canadian winter landscape, especially when you envision all of those awesome turtles beneath the ice, breathing through their butts.

Jacqueline Litzgus, Professor, Department of Biology, Laurentian University

Brazil is giving prisoners ayahuasca as part of their rehab

In this June 22, 2016 poto, a man moves a cauldron used for brewing a psychedelic tea locals know as the Holy Daime in Ceu do Mapia, Amazonas state, Brazil. Ayahuasca brew is sacred to Ceu do Mapia villagers, who use it in rituals that blend together Indian beliefs with Roman Catholicism. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres) (Credit: AP)

Some of Brazil’s violent offenders are being offered the opportunity for radical rehabilitation via the powerful psychedelic experience of the ayahuasca ceremony.

Rather than the system of continued abuse and alienation many modern prisons employ, some of Brazil’s prisons are starting to offer holistic services to encourage rehabilitation in inmates. Services offered to selected Brazilian prisoners include guided healing practices like yoga, reiki, meditation, and in some locations, ayahuasca journeying. The goal is to provide rehabilitation to violent criminals and reduce the rates of recidivism after prisoners are released.

Ayahuasca is a psychedelic tea derived from the ayahuasca vine, Banisteriopsis caapi, and the Psychotria viridis plant, both of which are native to the Amazon. Ayahuasca ceremony is an ancient healing tradition used by indigenous Amazonian peoples. Some of those who have partaken of ayahuasca report profound psychological and sometimes physical healing experiences.

In recent years, ayahuasca has piqued the interest and curiosity of people in the rest of the world, culminating in an ayahuasca tourism industry throughout Amazonian regions of Central America. As ayahuasca’s international popularity has grown, so has research into its therapeutic uses. The plant has shown potential to help people recover from trauma, PTSD, addiction and depression, as well as cancers and other afflictions.

Brazilian prisons started to offer ayahuasca through the prisoners’ rights advocacy group Acuda, based in in Porto Velho. As Aaron Kase notes in a 2015 article:

“The ayahuasca program serves a dual purpose. Prison populations in Brazil have doubled since 2000, and conditions are grossly overcrowded, so the retreats are a kind of pilot to try to reduce recidivism rates. For now, it’s just a few inmates participating, and it’s too early to tell whether the treatments will help keep them from reentering the criminal justice system, but it’s at least a starting point.”

One inmate convicted of murder told the New York Times in 2015 about the lessons he had learned from his ayahuasca experience: “I’m finally realizing I was on the wrong path in this life. Each experience helps me communicate with my victim to beg for forgiveness.”

As the New York Times article explains in detail, supervisors at Acuda who get permission from a judge transport about 15 prisoners each month to a temple for ayahuasca ceremony.

“Many people in Brazil believe that inmates must suffer, enduring hunger and depravity,” Euza Beloti, a psychologist with Acuda, told the New York Times in the same article. “This thinking bolsters a system where prisoners return to society more violent than when they entered prison. [At Acuda] we simply see inmates as human beings with the capacity to change.”

April M. Short is a yoga teacher and writer who previously worked as AlterNet’s drugs and health editor. She currently edits part-time for AlterNet, and freelances for a number of publications nationwide.

Tina Brown made her bed with Harvey Weinstein and the golden age of magazines was born again

Tina Brown (Credit: Getty/Angela Weiss)

About twenty years ago, when I was a reasonably sought after magazine writer (a breed that no longer exists), Tina Brown asked me to breakfast. We met somewhere in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, not far from the headquarters of Talk, the magazine she was then editing in a doomed partnership with Harvey Weinstein. (Yes, that, Harvey.) I was excited and a little nervous. Brown, who had so famously roused first Vanity Fair, then The New Yorker, from their cultural torpor, was a bit of a hero in my book.

To begin with, she’s a brilliant writer, a trait boldly on display in the recent publication of “The Vanity Fair Diaries,” a book so filled with crackling bon mots, I found myself continually making exclamation points in the margins. Her then boss, S.I. Newhouse (recently deceased), heir to a newspaper fortune that kept the often money-losing Conde Nast titles afloat, the Medici to her Da Vinci, and a man not particularly gifted in the looks department is described, variously, as a “hamster” (!), “Caligula” (!) and a “pensive Hapsburg hanging in the Prado.” (!!) When she hadn’t heard from him in a few days, she began to wonder “what’s happening in the hamster cage.”

Brown had invited me to breakfast because I had written a well received piece for the magazine about an attractive, successful young woman who could not find a man to settle down with, thus embodying the zeitgeisty conundrum of feminism in the 1990s — once you’re making your own dough, it can be hard to make the compromises necessary to a committed relationship. Brown had smartly titled the article, “Picky, Picky, Picky,” a phrase plucked from a quote the woman had used to describe herself.

“I want you to write an article,” Brown leaned forward and fixed her knowing blue eyes on mine, “called ‘the “fuck you” years.’”

I stared woefully at her expensively blonded hair, the upturned collar on her cotton shirt and the pearls around her neck.

“The what years?” I asked. It was a terrible idea and I had zero desire to write it, but so much desire to please her!

“You know, how you reach those years when you just don’t give a shit what people think anymore?”

I didn’t, actually, know what she meant because, at the time, I very much did give a shit what people though. I still do. When the guy from AAA comes to jump my car battery because I stupidly left my hybrid running for a week (hey, they’re really quiet!), I feel compelled to be friendly to him. British people — especially ones who have graduated from Oxford — don’t feel this way. They arrive in the city professing to adore America’s meritocracy but then focus all their attention on their equals or, “betters,” the mere concept which makes most Americans gag. Brown was an assiduous chronicler of the parties she attended with the rich and famous of that era, many of whom are now dead. That social whirl was a crucial element to Brown’s success — at Tatler, the British magazine where she made her name — she was the scrappy brat thumbing her nose at the establishment. In New York, she found many of her best stories by cozying up to the establishment. In England, they haven’t forgiven her for it, but in New York, social climbing is a way of life.

With her 300 blowouts a year, Brown was living the life of an executive, but inside she was still the canny writer, hoarding details for the day she would pull a Truman Capote and brutally (but oh so deliciously) bite the hand that had fed her. The hamster isn’t the only one who comes in for a goring. The Vanity Fair she inherited was a“flatulent, pretentious, chaotic catalogue of dreary litteraturs . . . ” Actress Claire Bloom is “a high-minded humorless bore.” Painter Julian Schnabel is a “predatory starfish” trying to break in line at a movie screening. She could do the journals because she did not drink alcohol (another thing she and I don’t have in common). Attending those parties without drinking seems like dental surgery without Novocaine, but that’s why she got the big bucks. Actually, for a long time she did not get the big bucks, and her quest to wrest more money out of the hamster is, in many ways, the most compelling part of the book.

Money is always on her mind. “Harry and I were paid half as much then as we are now and never talked about money. Now that’s all we seem to talk about. Money here gets into the blood like a disease. An unsettling itch that colors everything.” Conde Nast is a privately held company, so the numbers are never public, but S.I. was always telling her how much money the magazine was losing until, finally, it wasn’t. Mindful that a well paid queen lording it over low paid minions won’t be popular for long, she generously spread the wealth, raising payments to writers from a mingy $1 a word, to $2, $3, $5, even $10 a word and signing them up to contracts so the money would arrive monthly. All of a sudden, magazine writing became a viable profession (assuming you were young and uninterested in home ownership).

As we all know, the internet put an end to all that. Reading her accounts of freewheeling assignments and unlimited expense accounts will make anyone in the business nostalgic for the old days. Nowadays, you’re lucky to get a dollar a word. And if you’re thinking maybe you’ll unionize to negotiate for better wages, think again. (See Gothamist and DNAinfo.com.) At least the ax is coming for editors as well. Rumor has it that Tina Brown’s replacement, Graydon Carter, was making $2 million a year when he announced his retirement a few months ago. His replacement is said to be making $400,000 a year.

At Talk, Brown was paid a stunning $3 million a year, but when she asked me to write a piece about the “fuck you” years, I think she was beginning to understand the enormity of the mistake she had made by throwing her lot in with the odious Harvey Weinstein. Better a gentlemanly hamster than a potted plant onanist. To those of us in the business, Brown seemed like the quintessential superwoman, impeccably coiffed, charming to speak with (assuming the conversation didn’t run over 25 minutes) and full of energy but, as the book reveals, she was actually struggling with the many pressures of having it all. She loved her brilliant husband, Harry Evans, but he was always, always working, leaving the donkey work of mothering to her, something she both adored and abhorred. She had no trouble firing deadweight editors but kept a detested nanny working for years. It was only when she overheard the woman saying she hated Brown, that she finally gave her the boot. No wonder she sometimes felt like giving the world the middle finger.

In the end, I did write another piece for “Talk.” At the time, the headlines were filled with the infidelities of then president Bill Clinton and the toll it had taken on his wife and daughter, Chelsea. Brown had the genius idea of gathering together the daughters of famous men who were also known for their infidelities and asking how it felt to read about their father’s peccadilloes in “The New York Post.” By promising anonymity and leaning on every social contact the magazine had, we were able to bring together five or six young women to discuss the phenomenon. I remember being queasily stunned and moved by the complexity of their emotions, especially one woman’s confession that she preferred to identify with her philandering father over her morose mother, the victim. “He is obviously having such a better life,” she observed.

The piece was accepted, scheduled and then mysteriously moved to a back burner, never to be seen again. When I asked my editor what happened, she said there was a rumor that Tina had mothballed it in order to mollify Hillary Clinton, whom she was courting for a profile. I always believed that explanation — magazines are like miniature kingdoms where egos need massaging and manipulating to gain the access you need. When the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke, I began to wonder if there was an even darker explanation, but I suppose I’ll have to wait for the sequel to find out.

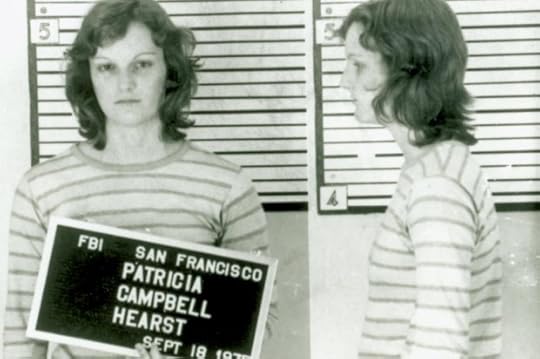

“The Lost Tapes: Patty Hearst” shines a jaundiced light on celebrity culture

"The Lost Tapes: Patty Hearst" (Credit: Smithsonian Channel)

So, I just watched “The Lost Tapes: Patty Hearst,” a new documentary which debuted last night on the Smithsonian Channel as part of the network’s Lost Tapes franchise. In its promotional material, the producers promised to air images and audio recordings that had not been seen or heard by the general public since the 1970s. Presumably, this is to shed new light into the dramatic story behind the Hearst kidnapping.

Does it succeed in doing this? Yes, to such a degree that it sets the standard by which all future attempts to depict the ’70s era irresponsible super-rich must be judged.

It makes sense that this particular topic continues to fascinate us. The 1970s was a decade of tremendous political upheaval — you had the Vietnam War, Watergate, the energy crisis, economic stagflation — and, like our own time, it was one in which the rich seemed to get away with everything. Within the past decade or so, we’ve seen Wall Street bankers torpedo the economy and leave taxpayers holding the bag, a con artist like Donald Trump get caught lying over and over again (including most recently denying that he boasted about committing sexual assault) while still being elected president and powerful men from all walks of life successfully cover up their sex crimes.

By these standards, the offenses of heiress Patricia Hearst seem almost tame by comparison. After being kidnapped by a radical left-wing terrorist group called the Symbionese Liberation Army, Hearst soon became a passionate member of the group, sharing in their cause and denouncing her family, fiance and former way of life. In a streamlined and efficient way, the new Smithsonian documentary lays out the chain of events from Hearst’s kidnapping through her trial, conviction, commutation and eventual pardon. The documentary devotes particular detail to showcasing the tapes she left for authorities that demonstrated the extent of her indoctrination.

Of course, unlike the vast majority of individuals in the Rich People Who Get Away With Awful Things canon, Hearst does have a plausible argument for her own victimhood. Because she started out as a kidnapping victim, it is entirely possible that her conversion to far left-wing politics was as much the result of Stockholm Syndrome as a genuine shift in her belief system — indeed, perhaps even more so. Wisely, the Smithsonian documentary touches on these possibilities without trying to definitely answer these questions on its own.

To be fair, I don’t think the Patty Hearst case is being revisited because of new information. If I had to guess, I would say that Americans are regaining an interest in a number of 1970s-era crimes because so many of them played out the class and racial tensions that have risen to the fore in our own decade.

This was the case even before Charles Manson’s death, although the timing there was eerily apropos, considering the current zeitgeist. It explains why there are not one but two projects in the works about the kidnapping of John Paul Getty III — the upcoming Ridley Scott film “All the Money in the World” and the Danny Boyle television series “Trust.” On that occasion, the kidnapping had much less idealistic motives; Getty’s kidnappers straight up demanded ransom money for the heir’s safe return.

Nevertheless, there was still an intrinsic fascination in seeing the super-rich dragged down to everyone else’s level. The same, no doubt, inspired the fascination with Manson, which was revived earlier this year when initial reports came out that he was having medical issues. Based on the man’s infamy, you would think that his notorious Manson Family had killed hundreds. Yet Manson himself was only found guilty of either murdering or conspiring to murder seven people — but seven rich and famous people, most notably the rising star Sharon Tate. Had Manson committed his heinous crimes against ordinary civilians, it is highly questionable whether he would have become a cult figure today.

Which brings us back to the latest Hearst documentary. It’s a story that hinges around understanding the mind of an heiress who, ultimately, feels more like a pawn in other people’s games than an active player of her own. Without Hearst’s wealth — which, it must be emphasized, she did not earn on her own — her tale would have been long ago forgotten, with Hearst herself rotting away in a jail cell for crimes that she indisputably committed and for which she was rightfully convicted.

The mere fact that we’re still following her story, and treating her experience as if it’s something special, reveals that the super-rich managed to “win” here, even if one of their own did experience a harrowing ordeal for more than a year. Even then, the fame that came with her name gave her a cushion when her dramatic tale was over — yes, she served several months in prison, but her sentence was soon commuted by President Jimmy Carter, and eventually she was outright pardoned by President Bill Clinton.

If “The Lost Tapes: Patty Hearst” had made the extra effort to shed light into the mind of the kidnapped heiress, it could have informed what is otherwise a lame, if hardwired, obsession with the rich and famous in American culture. As it is, this narrative is just one more in a series of sensational stories that criticizes our class system but which, by virtue of their very existence, also celebrates it.

“Word-for-word:” Alex Jones boasts that Donald Trump repeats things the host tells him

(Credit: Infowars)

Conspiracy radio talker Alex Jones boasted on Sunday that he has regular, private conversations with Donald Trump and that the president routinely parrots things that Jones tells him.

The Infowars founder claimed that he has “personally witnessed” Trump repeat “word-for-word” information that Jones has shared with him in private conversations “at least five or six times.” Trump loves listening to things that random people tell him, Jones said. The president writes down the hot scoops and then asks close aides to verify the information via methods Jones did not specify.

“They call that easily influence or he believes the last thing he heard,” Jones said dismissively.”When he gets told about a Harvard study showing that millions of illegals voted, he goes and looks into it and finds out it’s true. I mean that’s what Trump does.”

Despite Jones’ claim, the evidence that millions of non-citizens voted in 2016 is essentially non-existent.

According to Jones, Trump also likes to take advice from people he meets while campaigning, even though in political circles, rally attendees are notorious for promoting conspiracy theories and nonsense.

“You notice he’ll be on the campaign trail people are handing him stuff or he’ll start writing things down,” Jones said.

He then compared such political statements to customer feedback that Trump collected while operating his real estate empire.

“He’s obsessed with what people tell him,” Jones said. “At his hotels and his condos, Trump routinely will just walk around for hours and just write down what people think and what they say and then blow up at people.”

“It’s not like something special that I’ve told Trump stuff, he’s gone and looked into it and then when he found out it was true, responded,” the fake news impresario said.

Trump carries around numerous yellow pads on which he writes political tidbits and conspiracy theories and then dumps them off on assistants to verify them for him, according to Jones. “He’ll just have pockets full of it,” Jones said. “He gets on his jet and then pulls them out and starts looking at it. And then talks to an aide and has them go look it up for him and bring it back to him.”

According to Jones, Trump pursues such random theories late into the night most evenings. “Until 2 in the morning most nights, he’s in there checking stuff,” the host claimed.

Jones’ description of Trump’s late-night activities tracks well with what has been observed of the president’s Twitter habits. It also tracks with what several mainstream media sources, whom Trump frequently derides as “fake news,” have reported about his nights.

“Once he goes upstairs, there’s no managing him,” one anonymous Trump adviser told the Washington Post in April.

The Trump-Infowars nexus is multi-directional.

In May, Jones boasted that Infowars contributor Mike Cernovich — with whom he recently discussed a wide-ranging conspiracy driven by an unknown artificial intelligence to promote Islam — was in close contact with Trump’s sons, Donald Junior and Eric. Cernovich has also boasted that White House chief of staff John Kelly would be unable to stop the president from receiving conspiracy material because the younger Trumps give it to him first-hand.

“If it’s good enough, Don Jr. will give it to him,” Mike Cernovich, an Infowars contributor and chief promulgator of the Pizzagate conspiracy, boasted to BuzzFeed in August.