Lily Salter's Blog, page 224

November 30, 2017

Like Game of Thrones? You’ll love Game of Floods

Kit Harington in "Game of Thrones" (Credit: HBO/Helen Sloan)

An underlying tension running throughout HBO’s epic fantasy series “Game of Thrones” has to do with what will happen once winter has come. Game of Floods poses a similar threat (albeit without the gorgeous cast). But you don’t really need the Dragon Queen or Jon Snow to make prepping for climate disaster fun, do you? That’s what officials in Marin County, California, are banking on.

A report issued by the Bay Area county predicted that within 15 years, “billions of dollars worth of private and public property — some 700 buildings across 50 acres of Marin — will be threatened by flooding.”

Meanwhile, MarinCounty.org warns that when it comes to sea level rise, the future is now:

Rising sea levels and more severe storm flooding as a result of climate disruption are impacting us here in Marin County now. Even when the sun shines, Marin County already experiences more frequent flooding, both on the Pacific coast in west Marin and along our bay shorelines, impacting roadways, drainage and utilities, and disrupting people’s lives. These impacts are expected to increase in frequency and severity as sea level rise accelerates.

In response, Marin officials invited the public to propose a plan of action. Realizing the need to motivate the public to change their behavior, a group from Marin County’s Community Development Agency and Department of Public Works came up with an idea Tyrion would love: Game of Floods. (Learn how to play the game.)

The year is 2050 and residents of the fictional Marin Island face imminent disaster as sea levels rise. Players place themselves in the position of planning commissioners tasked with helping the doomed islanders strategize ways to minimize destruction using limited resources (an effort that has already garnered Marin County a national award for public outreach by the American Planning Association).

Like other resource management games such as Pandemic, Game of Floods is all about encouraging collaboration against a common threat. This is realized through the use of a hexagonal board demarcated by colored flood zones representing areas such as a seabird colony, school or an electrical substation. Players begin the game by discussing whether to protect, adapt or retreat from an area.

If, say, the group decides to go with protection by building a levee, this might prevent flooding but will seriously drain the budget. Another option for adapting — dune restoration, for example — will cost a lot less, but have a limited effectiveness. Once consensus has been reached, stickers are placed on each section of the board to reflect the group’s strategy.

The strategy’s success is determined by a guide who tallies up the total costs of the environmental and human impacts of the group’s decisions. This is not your typical winner/loser board game. Instead, the game is meant to be played multiple times, ideally at a local meeting or workshop, so community members can begin to wrap their heads around the pros and cons of various adaptation methods and the broader implications of rising tides.

“We face difficult and complex decisions in responding to increased threats of sea level rise, and playing the game helps people become our partners in the process,” Roger Leventhal, a Marin County public works engineer who helped come up with the idea, explained to the Times-Picayune.

The key to understanding is in the deliberation. “It’s the first adaptation game I’m aware of,” said Alex Westhoff, a planner from the Marin County community development agency who co-devised the game, in an interview with Citylab. As Westhoff explained, by getting the public to understand the difficulty of his job by framing outcomes through specific actions and their consequences, they can grow familiar with the reality of rising sea change. In turn, this threat becomes a more tangible reality, which means that the public begins to understand their own role in mitigating disasters. The fact that the game is also “fun and engaging” certainly helps, added Westhoff.

The first round of Game of Floods was played during a 2015 workshop held in West Marin. From there, the game took to the road touring conferences around California, where it soon got the attention of universities and preservation societies, not to mention the EPA and FEMA. In total, Westhoff estimates that Game of Floods has been played by about 1,500 people in workshops and classrooms throughout the country. More recently thanks to grant funding, Marin County is turning the game’s informal print-it-yourself packaging into an actual box set that will be available for purchase.

How much can a game make a difference, you may ask?

“We’ve played the game in a wide variety of settings,” said Westhoff, “and consistently the energy and enthusiasm that participants show gives us hope that we can make real progress.” To this Westhoff added that the game has already inspired Marin County locals to make more of a concerted effort to restore “eroded beaches with fresh sand and oyster habitats.” Feedback from players has also even helped the local planners think of alternative strategies for real-world adaptations.

“It all boils down to getting a conversation started about a very important topic,” Roberta Rewers, a spokesperson for the APA, said to Citylab. “It visualizes what could happen in a community, and it gets people thinking about how choices have impacts.”

We’ve already come too far to prevent the effects of climate change. But if we start dealing with those effects in the present, we can be more prepared for the future. Game of Floods is a good start, and will hopefully inspire more action in the real world, before winter really comes.

Robin Scher is a freelance writer from South Africa currently based in New York. He tweets infrequently @RobScherHimself.

Did Trump’s presidency trigger the movement against sexual harassment?

(Credit: Getty/Christopher Furlong)

The cascade of sexual harassment accusations over the past month has moved from high-profile men to lesser-known people in sectors such as higher education and the restaurant industry. In an important and fundamental way, the ground beneath us has shifted: Victims everywhere have lost their patience and their fear, and are finding willing listeners.

A question worth asking is: Why has it shifted now?

#Metoo and beyond

The current outpouring of allegations may seem sudden, but it isn’t surprising if you’ve been tracking the massive swell in women’s activism over the past year, as women’s studies scholars like me are doing.

Yes, the viral #MeToo campaign has been instrumental in raising this issue. According to Facebook, nearly half the people in the United States are friends with someone who posted a message about experiences of assault or harassment. But #MeToo draws its steam from other collective efforts. Even before #MeToo, the 3-million-strong private Facebook group Pantsuit Nation, founded just before Election Day 2016, witnessed hundreds of thousands of women breaking their silence about gender-based violence, among other topics. The Women’s March on Jan. 21 was the largest single-day globally coordinated public gathering in world history.

Over the past year, there’s been a clear spike in the number of U.S. women running for political office. Emily’s List reported that in 2017, more than 16,000 women expressed interest in running, compared to the 920 women who did so in 2015 and 2016 combined.

I would argue there’s a single thread running through all these phenomena: a fierce outrage about the election of Donald Trump.

Women activists are, of course, responding to a range of economic, social and political issues that a Trump presidency raises. But one of the most galling provocations is that Trump acknowledged being a sexual predator and faced no actual consequences. He was recorded saying that he used his star status to forcibly kiss and grab women — and still ascended to the White House. He has been accused of sexual assault three times — by an ex-wife, business associate and a minor — in lawsuits that were later withdrawn. Sixteen women have accused him of sexual harassment. In my opinion, the reason none of these accusations has gathered traction is because of competing news cycle distractions and the pressures his accusers face.

For many, Trump represents the ultimate unpunished sexual predator. Right after the election, therapists and counseling centers were reportedly flooded with patients — especially women patients — seeking help with stress and processing past sexual traumas. Now, one year into the Trump administration, with the ballast provided by women’s feverish organizing and the instant power of social media, I see the initial anxious response to the election mutating into something else: a collective emboldening. Even if victims of sexual predation cannot affect this presidency, they can try to fix other problems. Trump has made the comeuppance of other powerful men feel more urgent.

There’s a sociological concept that captures what’s afoot: “horizontal violence.” This term describes situations where people turn on people in their own lives when provoked by forces beyond their control. The Brazilian philosopher Paolo Freire used the term in 1968 to describe substituting a difficult powerful target with a more accessible one like peers or kin. Those who use horizontal violence are typically members of oppressed groups without easy access to economic resources or institutional channels of expression such as the law or the media. One example is when low-income men who are experiencing job instability take out their frustration on intimate partners.

It is, of course, inaccurate to term what sexual harassment victims are doing “violence,” so a better term in this situation might be “horizontal action.” It is also true that most allegations involve men who have greater power than their victims; in this sense, the action is not exactly horizontal. Nonetheless, the fact that victims are naming their colleagues in such great numbers suggests an awakening: They no longer want to protect their professions and careers nor play along with open secrets. It feels important to topple those perpetrators within reach. Trump’s impunity has, I suggest, provoked the impatience and fury at the heart of this movement.

This speculation is, of course, hard to prove, since the private injuries of victims can sufficiently explain the anger they feel. Victims who have spoken out might not openly describe Trump as the first cause for their frustration or bravery. But the frequency with which Trump is described as a trigger is telling. We need to theorize, on a cultural scale, why this collective disruption has happened now rather than, say, two years ago, when Bill Cosby was accused by multiple women, or last year, when Roger Ailes was deposed.

As we dissect the implications of what some call “the Weinstein effect,” I suggest we notice something else in the very air we breathe: a deep frustration that a self-confessed sexual predator remains — thus far — immune.

As we dissect the implications of what some call “the Weinstein effect,” I suggest we notice something else in the very air we breathe: a deep frustration that a self-confessed sexual predator remains — thus far — immune.

Ashwini Tambe, Editorial Director, Feminist Studies; Associate Professor, Department of Women’s Studies, University of Maryland

Domestic workers face rampant harassment on the job, with little protection

(Credit: Rob Marmion via Shutterstock)

Content warning: This article contains descriptions of sexual harassment and assault.

Isabel, 59 and an immigrant from Guatemala, was vacuuming her employer’s bedroom when he attempted to rape her.

“I was able to leave, and I never went back to that job,” Isabel, who prefers not to share her last name, told Truthout. “But I didn’t tell anyone.”

The incident took place 19 years ago, when she was a housekeeper in Chicago.

In the wake of the Harvey Weinstein story that broke in October, with more and more famous entertainers revealing their experiences of harassment and assault in professional settings, many perceive this moment to be a turning point for women’s ability to speak out about sexual assault.

Yet many women in the United States are presently enduring harassment and assault that they dare not publicly share for fear of losing their job, or experiencing other forms of retaliation, including deportation. These women include the approximately 2 million domestic workers — nannies, housekeepers and caregivers — in the United States, who work and sometimes live inside of the homes of their perpetrators.

The vast majority of domestic workers are women, and many, like Isabel, are immigrants and women of color. The sector is known for low wages and wage theft. Immigrant women hired as domestic workers are sometimes threatened with rape if they displease their employer.

“I almost always felt unsafe, or at least concerned about my safety, in a lot of jobs,” Isabel said. “I’d be entering strangers’ homes. I would often carry my money on my body so if I needed to leave quickly, I could.”

“These workers are isolated,” Almas Sayeed, supervising attorney at the Home Care Worker Team for the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) told Truthout. “It’s one of the reasons that they are vulnerable, just like the women in Hollywood we are hearing about. They are alone with their perpetrators, and they’re trying to keep their job. It makes it very difficult to get them to talk about these issues.”

Sayeed recently filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) on behalf of a New Mexico-based home care worker in her early 50s, “Linda,” whose 67-year-old male client has been inappropriately touching her breasts and lower back, and refuses to stop. The complaint alleges that when Linda tried to tell her employer — a private agency that contracts out domestic worker services — her manager at the agency began sexually harassing her as well.

Unlike Angelina Jolie, Selma Blair, Rachel McAdams and the other actors who have come forwarded recently, Linda is choosing not to speak with the press, for fear of losing her job.

Linda’s experience reminds us that women across a wide range of ages and professions are harassed and assaulted. While many women actors are speaking out about abuse that took place in their early 20s or before, domestic workers like Isabel and Linda are oftentimes middle-aged women who are continuing to experience sexual harassment and assault on the job.

Moreover, many domestic workers are mothers and grandmothers who are providing for their families. Quitting isn’t always a feasible option and losing their job could be economically disastrous.

Indeed, the sectors with the highest rates of sexual assault include low-wage sectors, such as farm work, and the restaurant and retail industries.

The history of domestic workers being sexually harassed and abused by their employers dates back to the days of slavery. In addition to having no legal freedom or power over their own lives, enslaved people who labored in US homes were subject to rape and sexual assault.

One enslaved woman wrote, “If God has bestowed beauty upon a slave woman, it will prove her greatest curse. That which commands admiration in the white women only hastens the degradation of the female slave.”

Slaves who labored inside of homes were extremely isolated. Many enslaved women — whether they were working inside of homes or not — were raped and forced to bear children by their male masters.

These indignities reappear in modern domestic workers’ lives.

Today, worker centers like Arise Chicago and the Miami Worker Center, which are nonprofit organizations that advocate for low-wage or immigrant workers, are helping to grow workers’ power and ability for self-determination. In line with this mission, these centers are providing opportunities for domestic workers to share their stories — as well as report the abuse when it happens.

Like Isabel, June Barrett has chosen to speak publicly about the sexual harassment she faced as a home care worker. Barrett, 53, is a Jamaican-born domestic worker and organizer in Miami. She has worked as a domestic worker since the age of 16 and has experienced sexual assault on the job.

“For a long time, I had to stay silent,” Barrett told Truthout. “I had to put up with unwanted kissing, groping of my breasts, because I needed work, I needed to pay rent.”

Barrett says she now feels comfortable speaking out because of her activism with the Miami Worker Center. Barrett told her story of sexual harassment at the first Florida Domestic Workers Assembly, a July 2016 conference that included domestic workers, city commissioners and legislators.

“The men that we work for? They are still in plantation mode. They still think we are their property, they think it is okay to say sexually suggestive things to us,” Barrett said.

Advocating for Protections

In some states, new laws are helping codify protections for domestic workers who experience harassment or other abuses, including wage theft and retaliation.

Several of the eight state domestic workers’ bills of rights that have been enacted include protection from sexual harassment. New York’s Domestic Workers Bill of Rights was enacted in 2010. The first in the country, it protects individual domestic workers hired by families.

The , enacted in 2016, includes domestic workers within Illinois’s Human Rights Law, which protects against sexual harassment.

And Oregon’s Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, enacted in 2015, includes protection from harassment as well.

Critically, many of these domestic workers’ bills of rights apply to employers who only employ one worker, in addition to those who employ multiple people. Typically, anti-discrimination legislation only covers employers who hire a larger number of employees. Federal anti-discrimination law only applies to employers who have 15 or more employees. But many domestic workers employ themselves or work for smaller companies, and they need codified protection from harassment as well.

This gap in protections points to the historic exclusion of domestic work from federal employment protections. Major labor legislation of the New Deal era, including the Fair Labor Standards Act, which set a minimum wage, and the National Labor Relations Act, which protected collective bargaining activity, did not protect domestic workers.

Moreover, when it comes to sexual harassment and assault, domestic workers face unique circumstances that render longstanding laws inadequate to address their needs.

“Domestic workers are often alone in private residences, so they don’t usually have available witnesses or other evidence that a worker in a more traditional workplace may have, and yet, under the law, they are often held to the same standard,” Rocio Avila, NDWA state policy director, told Truthout.

Many domestic workers’ bills of rights do require that workers file a complaint with the relevant state agency within one year of the harassment taking place.

Ensuring more domestic workers know about emerging legal protections and the potential for relief can help domestic workers stand up for themselves, Avila said. That is where advocacy groups like Arise Chicago and the Miami Workers Center play a critical role. These groups, affiliates of the NDWA, conduct “know-your-rights” trainings and organize domestic workers throughout their communities. Mujeres Unidas y Activas (MUA), an NDWA affiliate in Oakland, runs a sexual assault hotline for domestic workers to report abuse.

In addition, state agencies that investigate employment discrimination and harassment claims should be equipped to effectively and expediently investigate claims from domestic workers, Avila said.

“Enforcement agencies should assess the threat of retaliation domestic workers may face for speaking out, and prioritize their investigations based on that,” Avila said. “These agencies should recognize how vulnerable domestic workers can be and process their claims expediently in partnership with workers’ rights organizations.”

Organizing efforts, coupled with state and local policy, are beginning to help domestic workers speak out and remove themselves from abusive situations. At the same time, domestic worker advocates are also being elected to policymaking positions — further strengthening the domestic workers’ movement’s ability to advocate for workers. Lydia Edwards, formerly an attorney who represented domestic workers with the Brazilian Worker Center in Massachusetts, was recently elected to the Boston City Council.

While this is all important evidence of progress, it is piecemeal. A federal domestic workers’ bill of rights would help ensure that all domestic workers throughout the country are protected, Sayeed said.

“Before the 2016 election, we were on [the] precipice of moving legislation forward at federal level,” Sayeed said. “My hope is that eventually all domestic workers will be protected against harassment and retaliation by a federal law.”

Copyright, Truthout. Reprinted without permission.

GOP congressman demands competitive districts: “I guarantee you things would change here”

(Credit: AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Rod Blum is a rarity in Congress — a member who actually wants a competitive district and a real challenge every Election Day. Blum, a Republican, believes this makes him a better congressman. He says that it requires him to listen to — and represent — the feelings of Democrats and independents as well as his fellow Republicans. In an op-ed in The Hill this fall, Blum wrote that he is “honored to represent a competitive district drawn by a nonpartisan redistricting commission.” That requires him to hear out everybody, he suggested, “much like a small businessman must listen to his customers.” Blum also signed onto a bipartisan amicus brief in Gill v Whitford, the Supreme Court case on extreme partisan gerrymandering. We caught up with him last month to talk reform — and incentives.

Dave Daley: Your op-ed , as well as the brief you joined in Gill v Whitford, makes the case that fair districting is essential for a fair democracy. You suggest that allowing politicians to draw their own lines is an unfair perk of incumbency — and that one way to attack it is to frame it as in issue of the people versus the elites. But as you know, that would require incumbents, those elites, to put limits on themselves. Do you see any sense that your fellow lawmakers, of either side, might be ready to look at this in such a way?

Rep. Blum: It’s very interesting: I was not aware of what they had done in California. In a 10-year period – and there’s 53 congressional districts in California — one seat changed political hands. They passed a non-partisan commission to do the district alignments, and in 2012, 26 percent of the seats changed ands.

I’m from Iowa, where we have the same thing, a non-partisan commission in charge. It’s the best process in the country, and we have very competitive elections. Three of the four districts are competitive in Iowa. I represent a Democratic district, but I really feel this is so important – people are so frustrated with Washington because they feel like we’re not representing them. But when I look at any given year, 435 House seats, maybe 35 are competitive. I scratch my head and go “why?”

When you don’t have to go back and report to your constituents, and spent time with them and listen to them – you know, I don’t think you’re good as a representative. And what incentives are there for you to sit down with the other side and come to an agreement on something?

There’s none. Sitting down with the other side, if you represent an uncompetitive district, might earn you a primary challenge. Your incentive is not do that.

That’s right, there are very few incentives there.

So how does this affect governing? Do you see this within your caucus or in talking with folks on the other side? Is the behavior of members shaped by these incentives, by fear of a primary?

Yes. I’ve found that. I’m sure it’s the same in the Democrats’ conference. The biggest concern is being primaried. That’s the biggest concern.

And that pushes politics — and everyone’s behavior — to the extreme?

Exactly.

And makes people less willing to talk to one another?

You nailed it. You just nailed it. In a competitive district, that’s why I’ve stood up to my own party numerous times. I’ve voted against the Republican Party. I’ve voted against a sitting House speaker, John Boehner, because I campaigned on change. People want change. They’re tired of Washington D.C. and career politicians.

How would you fix this? Especially if the Supreme Court does not step in as you would like it to.

Well, if the Court does not step in, then it’s state by state. Some states do it right, and a lot of states don’t do it right. The people are going to have to bring grass-roots pressure. And we all need to talk about this more. I’ll guarantee you 95 percent of the people, your average person out there, when I say gerrymandering to them, they don’t know what gerrymandering is. We need to talk about it more. If people truly want representative government, we have to take care of this. It’s a big issue that congressional seats are not competitive anymore.

Both sides have gerrymandered for a long time, but the Republicans truly reinvented and mastered it with the REDMAP program n 2010 and 2011. Do you think there have been consequences from that for our politics, for how Congress works?

Yes. I think the consequence is what you alluded to a minute ago. We now have the two sides of Washington D.C. that don’t work together, because what’s the incentive to do it now? If — even in theory — every Congressional representative out of 435 had a competitive district back home, then I guarantee you things would change here and we would be forced to work together – even if we didn’t like being forced to work together.

I’m a career businessman and it all comes down to incentives. I understand how people respond to incentives. Right now, I don’t see where there are incentives to work together — because most of the people cannot work with the other side, and they’re going to get re-elected in a landslide.

5 worst media moments of last week

Thomas L. Friedman, NY Times columnist (AP Photo/Keystone/Peter Schneider) (Credit: Associated Press)

Saudi Arabia gets some top-shelf public relations help from U.S. media, alt-right chuds have meltdown over Twitter ban, and the most incompetent administration in history still manages to openly manipulate the media. We dissect these and more in this week’s five worst media moments.

1. Thomas Friedman writes creepy love letter to Saudi dictator-in-waiting.

What can be said about Friedman that hasn’t been said a million times by better writers? He’s tedious, venal, incoherent, morally repugnant hack who’s been phoning in power-flattering columns since I was in middle school. But on Thanksgiving he managed to find a new, heretofore unknown level of shamelessness, by running what was, in effect, a public relations piece for the Saudi Crown Prince – fresh off a recent purge of all his political enemies under the guise of “anti-corruption” and “reform”.

“Saudi Arabia’s Arab Spring, at Last“, the headline proclaimed. Evidently absolute monarch dictators can assert an “Arab spring” despite the entire point of the Arab Spring being to oppose such forces. Nonetheless, Friedman would continue for 2700 words painting the king-in-waiting for his bravery and courage. Glossing over the brutal, criminal war in Yemen as a “humanitarian nightmare”, Friedman insists his “biggest sin” was “moving too fast”. Evidently, mercilessly bombing the poorest country in the Arab world for two-and-a-half years falls below “being too goddamn passionate about reform” in the severity of sins ranking.

In the groveling interview, Friedman let’s Mohammed bin Salman, without pushback, call Iran “the new Hitler”, claim the anti-corruption investigation is “independent” (as is the custom in absolute monarchies), spew out vague reformist pablum, and even ends by comparing the prince to Hamilton from the Broadway show Hamilton (Why does he always work like he’s running out of time”? Friedman fawns). In Dante’s Inferno, sycophants occupy the second pit of the eighth circle of hell, grovelling in excrement that represents the insincere flattery of their words. There’s not, we will likely find out, a pit deep enough nor feces potent enough suitable for The Times worst columnist.

2. Trump plays media like fiddle over bogus Iran-HBO hack case.

It’s rare one has evidence the media is being manipulated in real time but such is the case this week with the sensational case of an Iranian national hacking HBO and stealing Game of Thrones scripts. The Washington Post reported Sunday that the Trump administration was pressuring DOJ lawyers to find any dirt on Iran or Iranian nationals in a broader push increase tensions with the country:

Last month, national security prosecutors at the Justice Department were told to look at any ongoing investigations involving Iran or Iranian nationals with an eye toward making them public.

The push to announce Iran-related cases has caused internal alarm, these people said, with some law enforcement officials fearing that senior Justice Department officials want to reveal the cases because the Trump administration would like Congress to impose new sanctions on Iran.

Here we have whistleblowers in the DOJ letting the public know, in no uncertain terms, the Trump administration was selectively seeking out cases to smear Iranians to undermine the Iran Deal, impose sanctions, and stoke a potential war. How did the media respond to this after a story broke the same day an Iranian national hacked into HBO? By mindlessly repeating the story without noting this glaring piece of mitigating context. Every outlet, from LA TImes to Buzzfeed to Reuters to Daily News to The Guardian to The New York Times ran with the “LOL Winter is Coming for this Iranian hacker” frame without noting it was part of a deliberate propaganda effort by the Trump White House. DOJ lawyers told us Trump was playing the media and it worked anyway. No one cared.

3. $32 million media campaign to seat Neil Gorsuch on Supreme Court funded by anonymous donor.

What would be the biggest scandal of the week in a healthy society – a single anonymous donor backing the PR campaign to seat a far-right judge on the Supreme Court — was relegated to minor coverage in our present hell timeline.

MapLight’s Andrew Perez and Margaret Sessa-Hawkins revealed Tuesday that the major group behind the push, the Wellspring Committee, had, “donated more than $23 million last year to the Judicial Crisis Network, which spent $7 million on advertisements pushing Republican senators to block President Barack Obama’s court pick, Merrick Garland. After the election, the network spent another $10 million to boost President Donald Trump’s pick, Justice Neil Gorsuch.”

The most offensive part isn’t even that billionaire donors can have such colossal influence over our nomination and electoral process; it’s that they can do so entirely anonymously. Not only can we not do anything about the rich shaping our perception on matters of huge political import, we can’t even know who is behind it. This should be an outrage, but alas, it’s just another dot on the sprawling map of monied influence we now accept as routine.

4. 60 Minutes, Washington Post completely omit U.S. role in Yemen slaughter.

Two major media outlets spent the past two weeks whitewashing US role in the famine and bombing of Yemen. In this time, the country’s leading National Security paper, The Washington Post, has published two editorials and an explainer on the conflict and omitted, entirely, America’s military role in the campaign that’s left 15,000+ dead, two million internally displaced, and one million with cholera.

Escalating the negligence was CBS News’ 60 Minutes that dedicated a whole 13-minute segment to the conflict and never once mentioned that the United States provides targets for the Saudi Royal Air Force as well as refuels and sells billions in weapons. America’s role in the worst on-going humanitarian crisis on earth just slipped into a memory hole.

5. Major alt-right accounts get banned from Twitter, have colossal meltdown.

Alt-right troll, master of the self-own, practitioner of self-macing, and part-time holocaust joke maker, Baked Alaska (a/k/a Tim “Treadstone” Gionet) was banned from Twitter this week for being an all around vile nazi-sympathizer. After having a meltdown at an In-and-Out Burger parking lot and yelling at random strangers he attempted to created a “secret” account which was quickly banned as well.

Twitter has finally got around to sort of maybe trying to tame its runaway nazi problem. The rules are still arbitrary and opaque but at least they finally decided to decertifying celebrity white supremacist Richard Spencer–though they couldn’t bring themselves to actually ban him. This, one assumes, would just be too far.

Adam Johnson is a contributing analyst at FAIR and contributing writer for AlterNet. Follow him on Twitter @AdamJohnsonNYC.

November 29, 2017

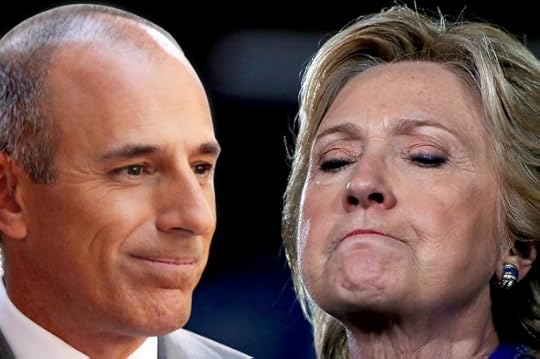

Matt Lauer and the emails: How accused harassers conjured a fake Hillary scandal

Matt Lauer; Hillary Clinton (Credit: AP/MediaPunch/Getty/Justin Sullivan/Salon)

While the details continue to be maddeningly obscure, it appears that Matt Lauer of NBC News is the latest powerful, wealthy man to take a very public fall after what NBC News president Andy Lack called “inappropriate sexual behavior.” In the wake of Lauer’s firing, a public discussion has erupted about previous accusations against him for sexist behavior, such as his public shaming of Anne Hathaway after a predatory photographer took an upskirt photo of her, or when Katie Couric complained that he “pinches me on the ass a lot” or when rumors swirled that he had run Ann Curry off “Today.”

Most of all, people are looking back to the way Lauer covered Hillary Clinton during the 2016 election. Even in a campaign season defined by unfair and sexist coverage of Clinton, Lauer’s slanted reporting was noteworthy. In particular, he was one of the most prominent proponents of the notion that it was a major scandal that Clinton had used her private email account to do official work as secretary of state, even though Colin Powell had done the same thing without controversy and multiple, thorough and seemingly endless examinations of her email history revealed nothing scandalous or even mildly interesting.

Lauer’s email obsession angered a lot of journalists, even journalists like Jonathan Chait of New York magazine, who isn’t exactly known for his woke views on women and power. In September 2016, Lauer did two hour-long interviews with each major-party presidential candidate. He gave the softball treatment to Donald Trump, letting Trump lie repeatedly without challenging or confronting him, and without really digging into Trump’s multiple real scandals. With Clinton, however, Lauer spent a full one-third of the interview on emails, even though her email history had been public, at that point, for a full year, and there was absolutely no way that interesting new information was coming out of it.

(Meanwhile, Trump was — and still is — refusing to release his tax returns, something Lauer didn’t bring up once.)

“At this point in the campaign, Lauer’s obvious sexism is not simply a problem of unfairness in the treatment of the individual candidates; such performances have serious consequences for the fate of the nation,” Adele Stan of the American Prospect argued at the time, noting that Lauer also spoke to Clinton condescendingly while letting Trump walk all over him.

It wasn’t just Lauer, either. When one looks down the lengthening list of prominent male journalists who have been credibly accused of sexual harassment, one thing that sticks out is that they were all obsessed with those godforsaken emails. Charlie Rose, Glenn Thrush, Mark Halperin, Bill O’Reilly: Besides being apparent sleazeballs, they were all big fans of the idea that the thousands of Democratic emails, some released by Clinton herself and some stolen by presumed Russian agents and leaked on WikiLeaks, would somehow turn into an earth-shattering scandal. WikiLeaks is, of course, an operation run by Julian Assange, an accused rapist who spent the election leaking emails that somehow never had the shocking revelations he insinuated readers would find.

Rose went after Clinton on emails like a dog after a bone. O’Reilly seemed certain that all these emails would somehow prove Clinton was guilty of something. Halperin could barely wipe the drool off his face, so certain was he that emails would be the end of Clinton. Thrush spent years of his career making sure that the public believed that “Clinton emails” was a scandal, despite the fact that all that work produced no actual information of value.

All this faith that Clinton had some deep, dark secret that her emails would eventually reveal proved for naught. Lots of chatter in the emails about TV shows and pasta sauces, but no scandals. Some grousing about Bernie Sanders dragging out the primary, but no evidence of illegal or unethical behavior. It was a big nothing-burger, but the relentless media drumbeat about “emails” meant that the American public was convinced there was a scandal — even as many were entirely unaware of the many corruption scandals surrounding Trump.

Now we find out that many of these journalists who seemed convinced that Clinton had a deep, dark secret were likely harboring guilty secrets of their own. Their baseless campaign of persecution led, directly or otherwise, to the election of a man so full of deep, dark secrets that he’s under federal investigation and still won’t release his tax returns.

It may not be obvious at first glance, but the email non-scandal was fueled by sexism, which was evident even before these sexual harassment accusations. At its heart, the whole story — which often verged on conspiracy theory — was rooted in misogynist myths about the inherently deceitful nature of women. This paranoia is why women are usually subject to more chaperoning and control than men. It’s why religious conservatives have spent four decades in a rage because the Supreme Court found in Roe v. Wade that women have a right to privacy. In the 19th century, fear about what women might get up to if shielded from prying eyes led to widespread condemnation of letting women use the postal system.

This certainty that Clinton was somehow or other doing something nefarious with her emails was rooted in these ancient fears. That was why the story would never go away, no matter how many times it turned out that there was nothing interesting in her goddamn emails.

“We see that the men who have had the power to abuse women’s bodies and psyches throughout their careers are in many cases also the ones in charge of our political and cultural stories,” Rebecca Traister wrote, after the accusations against Halperin and others came out. Clinton’s narrative was controlled by “men whose gender-afforded power ensured that she would have to work around and against so many dicks.”

Perhaps the fake email scandal is the best example of this. So many men are not just threatened by ambitious women, but are eager to believe those women are hiding dark secrets. In many cases, those men are projecting their own sins — their own corruption, their own power-hunger, their own dark secrets — onto the women they loathe. And while watching a handful of them get fired after the fact is nice and all, it won’t mean anything until we start fixing the sexist system these men did so much to uphold.

We’re in a new Civil War

Roy Moore (Credit: AP/Brynn Anderson)

You don’t have to look around for a Confederate flag to know that the old battle cry of “states’ rights” is here again. This time, it’s not about the “right” to keep the races separate. It’s about the “right” to vote for a child molester. But understanding why it’s come to this takes some figuring.

What I’d like you to do is this: try to imagine for a moment living in a small town in the deep South — a town like, say, Gadsden, Alabama — surrounded by piney woods and sandy soil, the kind of place where everybody knows everybody else’s business. A lot of industry already moved offshore, to countries where they can pay workers even less than the right-to-work pittance they paid in Gadsden. Left behind are strip malls, Pizza Huts, Krispy Kremes, muffler shops, tire retailers, Dairy Queens, women selling Mary Kay cosmetics to each other.

Over there on Lewis Road you’ll find an old red barn set up as a horseshoeing business, with a long-dead rusted flat-bed truck up on blocks, and across the one lane black-top road, a 50-by-12 trailer home with peeling paint and an above-ground pool right next door to a ranch-style house with aluminum siding that has three cars parked on the gravel drive out front. Drive a little further, and you’ll find another ranch-style house with aluminum siding, and another, and another, and a truly amazing number of pick-up trucks parked in driveways in various states of disassembly or repair. And churches — lots and lots of churches — New Faith Community Church, and Faith Baptist Church, and Full Gospel Tabernacle, and James Memorial Baptist Church, just across the street from the Dollar General, and the Living Truth Christian Center, which is not far from the St. Paul Overcoming Church of God, which is just down Glenwood Avenue from Paden Baptist Church.

The small Southern town we’re imagining — say, a place like Gadsden, Alabama — has a population that is 34 percent black and 62 percent white, so it’s easy to imagine yourself as a citizen of either race. Now what I’d like you to do is imagine that you are one of the black citizens, and living in Gadsden, Alabama you hear this phrase over and over and over: our blacks. Let me say it again: our blacks. You also hear our negroes, and our ni**ers, but because Gadsden is under somewhat of a national spotlight and people are endeavoring to be seen as, ahem, inclusive, let’s have you imagine hearing from the mouths of your fellow citizens who are white is that you are one of our blacks.

Now what I’d like you to do is stop imagining, because that’s what you’ll actually hear in Gadsden, Alabama and towns like it all over the deep South. I know, because I’ve been there, and I’ve lived there, and years ago, I grew up there. I’ve been to Gadsden, and I’ve been to towns like it elsewhere in Alabama, and over in Mississippi, and down in Louisiana and up in Arkansas and Tennessee, too. You’ll be talking to somebody as I was some years ago when I passed through Fort Smith Arkansas — a guy sitting next to me at breakfast, to be exact — and you’ll hear them tell you that our blacks are different than the ones in Little Rock, or you’ll hear them say our blacks keep to themselves, or they’ll tell you that our blacks are good people, God fearing people. Because, you know, we’re not talking about their blacks, we’re talking about our blacks, and we know how to deal with blacks around here.

Or maybe you’ll be out at a dirt track in rural Tennessee, a place they nicknamed “Ducktona” because it’s close to the Duck River, and you’ll be watching late model race cars go round and round. And between races, when the noise of the un-muffled race cars isn’t deafening, you’ll hear someone sitting in front of you in the virtually all-white stands talking to his buddy, and he’ll say, well, our blacks aren’t like that, because they know their place around here. Or you’ll be in Louisiana south of Lafayette at a duck camp, which is to say, a place in the deep bayous where you go duck hunting, and you’ll be sitting in a wood-framed plywood bar set up on stilts so it won’t flood during hurricanes, and you’ll be listening to two fellow duck hunters, and one of them is telling the other that our blacks can’t be relied on anymore because they’ve been fed a whole load of bullshit by the goddamned Democrats, and now they don’t want to work, and that’s why we’ve got all these Mexicans and Cambodians coming in, because at least they’ll take the jobs in the chicken plants, and goddamnit, we’ve got to teach our blacks a lesson.

I’ve heard all of it, and I’ve heard worse, and I know where the phrase our blacks comes from. It comes from slavery, because the ancestors of the black people they’re talking about were actually owned by the ancestors of the people doing the talking, back when the phrase they used was our slaves. If their ancestors weren’t slave owners, some of them fought in the Civil War in defense of the right of plantation owners and other more wealthy Southern gentry to own slaves. We know this because Alexander Stephens, the Vice President of the Confederate States of America, declared as much in his infamous “Cornerstone Speech,” delivered in 1861 soon after the secession from the Union by Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas. Mr. Stephens, a former congressman from Georgia, was good enough to tell us that the newly formed Confederacy was “founded upon exactly [this] idea; its foundations are laid, its corner- stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

Of course as soon as they lost the war, Stephens and virtually every other so-called “leader” in the deep South dropped this rationale for the Confederacy and the reason they fought the Civil War in favor of a new “cause,” that of the sovereignty of the South and the right of self-government. And they would spend the next 150 years — in fact, right up until the present day — creating and maintaining the fiction that slavery had nothing to do with their “noble cause,” which they have maintained variously over the years was “states’ rights,” and their “honor,” and of course, the current favorite, their “heritage.” They would go on to erect more than 1,500 memorials to the Confederacy and its “heroes” all over the South in prominent locations, at least 718 of which are statues and monuments.

It gets worse. They also named roads and public plazas all over the South for their “heroes,” the generals who fought for slavery during the Civil War. Right there in downtown Gadsden is Forrest Avenue, named after Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Confederate general who led his army in battles including the battles of Franklin and Nashville. Before the war, Forrest was a wealthy plantation owner and slave trader. After the war, he was an early member of the KKK and led midnight raids and whippings of black citizens in a movement to keep them from voting during Reconstruction after the passage of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

You practically can’t turn around in Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama without seeing something named after a Confederate general — a road, a courthouse, a municipal building, a park. And they kept it up. I’ve been through parts of Alabama and Mississippi where highways and buildings are named for sheriffs and local politicians who were infamous during the Civil Rights era for their opposition to voting rights for black Americans. Remember all those fights in the South over textbooks, most famously the ones on the Texas Board of Education every few years over how the history books should be written? What do you think those rights have been over? You’ve got it. They’re sick and tired down there about how all the history textbooks are running down the founding fathers of the Confederacy and talking about “negative stuff” like slavery and such. Why, the Civil War wasn’t fought over slavery! It’s was fought over states’ rights!

What does all of this amount to? Putting our blacks in their place, that’s what. Every time they turn around, black citizens of those Southern states are being reminded who is boss. They’re being told they’re our blacks, because the Southern political leadership can shove the legacy of slavery in their faces, even while they’re denying it in the schools and history books with invented rationales for the Civil War. The maintenance of this fiction, backed up by the arrogant notion that they didn’t want “outsiders” coming in and telling them how to write their laws and run their elections, was the heart and soul of the Jim Crow era, the heart and soul of the massive opposition to integration and the Civil Rights Laws of the 1960’s.

And now it is the beating heart and soul of opposition in the South to same-sex marriage, to the rights of transgendered people, even to the right to vote in general. Shelby County v. Holder, the case which defenestrated the Voting Rights Act, originated one county over from Etowah County. Gadsden is its county seat.

There is a connective tissue between Gadsden, Alabama; Selma, Alabama; Philadelphia, Mississippi; Little Rock, Arkansas; and even now Charlottesville, Virginia, where Nazis and Nathan Bedford Forrest’s KKK marched last summer in opposition to taking down Confederate statues. They’re saying over and over again, in one way or another: we don’t want outsiders telling us what to do with our blacks. We don’t want to be told who gets to go in our public restrooms. We don’t want to be told that we shouldn’t vote for a man just because he’s a child molester. It’s about our right to self-govern, our right to vote for whoever the hell we want to!

We are in a new Civil War. They voted for plenty of guys who put on white hoods and burned crosses and more than a few who put nooses around the necks of some of “their” blacks. It’s about states’ rights all over again. Once it was about the “right” to own slaves. Now it’s about the “right” to vote for a redneck child molester by the name of Roy Moore.

Which way do you think they’ll vote on December 12?

“Vikings”: Our dark age, as seen on History

Katheryn Winnick as "Lagertha" (Credit: History Channel)

Themyscira is coming! Have you heard? Are you not seeing its approach? The evidence is all around us: strong women, finding their bravery and coming forth to take down men who have taken so much from them and all of us. Their confidence, their chances at career advancement, their hope of feeling safe and respected where they work and live.

Themyscira came for a number of men already, a few on Wednesday morning alone! NBC’s uber host Matt Lauer, “A Prairie Home Companion” host and non-prescription sleep aid Garrison Keillor, CW superhero series showrunner Andrew Kreisberg (who built a number of series around DC properties — isn’t it ironic, Wonder Woman fans?), Pixar founder John Lasseter, celebrity chef Johny Iuzinni, all knocked out of commission before lunchtime on the West Coast. Amazons are efficient!

But wait . . . is this uprising really going to be a sea change with lasting effects some of us (at least those of us named Megyn Kelly) seem to think it will based on our present point of view? Not to take the wind out our sails, sisters but remember: Themyscira, inspiring though it is, is a purely fictional creation. Wonder Woman’s homeland. As depicted in this summer’s blockbuster, it looks terrific! Flawless beaches, tremendous tailors, exciting workouts, a matriarchal society based on respect and honor, sure! Who wouldn’t want to go to there?

However, those seeking more realistic entertainment with parallels to what’s going on now, one that also includes marked differences that grant vicarious thrills and catharsis, should tune in to season five of “Vikings,” debuting Wednesday at 9 p.m. on History.

What that series shows us, especially in these new episodes, is that perhaps we shouldn’t be dreaming of Themyscira but digging to defend the ground we’ve already won — just like the women are doing in Kattegat.

The central seat of the late hero Ragnar Lothbrok (Travis Fimmel, who departed in a most memorable fashion in the fourth season) is now under the rulership of his ex-wife Lagertha (Katheryn Winnick), who seized power from the former queen Aslaug (Alyssa Sutherland , also gone) by force. It was hers first, understand, and it’s not like Aslaug was doing anything useful with it or could use a blade.

Anyway, Lagertha’s in charge now, a shield maiden who dealt with sexual harassers, abusers and otherwise exploitative men in her life by stabbing them to death. Harsh, sure, but effective. In this new season, she’s put down roots in Kattegat. Her people love her. She surrounds herself with a cadre of female warriors, and she’s so relaxed in her power that she assumes a Detroit lean on the throne.

Nobody is pinching that woman’s ass, that’s for sure. But a number of men are coming for it, her rulership and her lands.

A central catalyst of the #MeToo movement is a simple one — that women are human beings deserving of equal respect and consideration at the workplace, and have the same opportunities for advancement as their male counterparts. Workplace hostility, whether of a sexual nature or just plain cruel, discriminatory behavior based on gender politics, has cost women in ways that we’re only really beginning to account for in a fundamental way.

Thus it can be instructive and satisfying to look to Kattegat and Lagertha’s story, as coarse and brutal as it can be at times.

On Wednesday, Congressional lawmakers were set to vote on legislation requiring sexual harassment training for members of Congress and their staff. It is the very least they can do. Consider that more than two weeks ago two female members of Congress called for reform of the House’s sexual harassment policies.

“The present system may have been okay in the dark ages,” said California Rep. Jackie Speier. “It is not appropriate for the 21st century.”

But was it really OK back then? In the Christian world, sure. The women in ancient Britain suffered all kinds of indignities, which “Vikings” does not shy away from depicting. For women in the fifth season’s portrayal of the Islamic world, quality of life was a mixed bag. One in particular appears to have a sway over powerful men to such as extend that Bjorn wonders if she is the “Allwoman,” in the way that Odin is “Allfather” to the Northmen.

In Lagertha’s world, handsy shenanigans don’t fly. She dimmed her greatness in favor of Ragnar, but never let him get away with dishonoring her. She played along with a patriarchal ruler until his abusive behavior threatened to go too far; he tried to grope her publicly, she ended him on the spot and took over his earldom. Another man attempted to blackmail her; she pretended to share power with him, even agreeing to marry him, only to slice him into ribbons, walking solo down the aisle with his blood on her wedding dress.

Lagertha is shrewd and intelligent, a woman’s will personified and her rage distilled to the point of a sword. She trusts no one, fights for her place in the world, seizes power and holds it and takes her due, even if that puts a target on her back.

And she’s able to do all that precisely because she exists in the 9th century, as part of a non-Christian culture where free women farmed, trained and fought side by side with men. In “Vikings” men of honor and purpose do not ask the women in their lives to hold back.

Then again, the Scandinavia of “Vikings” is no utopia. The ruling clans murder one another with no repercussion and take slave on their raids. And series creator Michael Hirst does not ignore the truth of human nature; a terrible assault is suffered by a major character, a warrior, in an upcoming episode.

Lagertha’s saga is one of several major plot engines in the wider-ranging ambitious fifth season of “Vikings,” the first that fully departs from what Hirst steadily built over the past four. It’s to Hirst’s great credit that the fictionalized historic drama still feels as vital and exciting without Fimmel and other members of the cast as it did with its starting line-up, and that’s in no small part due to the show’s willingness to expand the world of these raiders and explorers, and their motivations, beyond the shows initial ambitions.

Concurrently season 5’s plot deals with the long shadows cast by the dead or deposed leaders who shifted the trajectories of their people, whether in the divided and weakened Saxon England where its new rulership, and a fiery warrior bishop named Heahmund (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) have transformed the stakes from the survival of their people to a war pitting Christianity against pagans and heathens.

Hirst’s contemplative view and portrayal of religion is unique among television series, and “Vikings” fascinates because of its insistent refusal to cast neither Christians nor worshipers of the Norse pantheon as heroes or villains or portray one way as superior to another. Indeed, Ragnar saw the merits and flaws in both and forged a lasting fraternal bond with a Christian monk he first captured and enslaved, and then freed and embraced as a member of his family.

In these new hours, however, religion takes a backseat to philosophy and legacy. With Ragnar gone, his sons are left to decide which part of their father’s legacy to honor. This creates a political schism that, again, may seem familiar.

Lagertha and Ragnar’s son Bjorn Ironside (Alexander Ludwig) takes up his father’s legacy of exploration, allowing the series to venture more deeply into the Islamic world and expanding Viking influence. Political power, on the other hand, rests with Ragnar and Aslaug’s son Ivar the Boneless (Alex Høgh Andersen) and the Great Heathen Army he raises with his surviving brothers Ubbe (Jordan Patrick Smith) and Hvitserk (Marco Ilsø).

Textbook accounts of Ivar, such as they are, recall him as a great military strategist. A major reason Andersen’s portrayal of Ivar on “Vikings” has made him a fan favorite is because although he lacks the use of his legs, he’s cunning, cruel, ruthless and a little insane. He despises being insulted and is obsessed with achieving a level of fame and a reputation that eclipses that of his father.

In Hirst’s view Vikings follow strength, even if that strength is demonstrably psychologically imbalanced and thin-skinned. He’s also obsessed with exacting revenge upon Lagertha, which eventually pits him against his own family. It also makes him a handy ally for the ambitious Harald (Peter Franzén), who unsuccessfully schemed to dethrone Lagertha and sees her rulership as weak. (He also plotted against Ragnar, so fair is fair.)

So yes — the new age does seem a little closer to the worst of the Dark Ages and still far, far away from the fantasy island of Wonder Woman’s birth. Justice appears to be moving swiftly for women right now. Maybe the tide will turn in the short run.

As for the long view, settle in. Look to the lessons learned, and still being learned in thrilling, shocking ways by Lagertha and her fellow women warriors on “Vikings.” Look to Kattegat, where victories are as sweet as they are bitter, and the battle for respect never truly ends.

The human faces of climate change

Filmmaker Dayna Reggero (Credit: Andrea Desky)

When I arrive at award-winning chef Katie Button’s downtown Asheville restaurant, Cúrate, Dayna Reggero greets me with a hug before I even have the chance to properly introduce myself. I apologize for being a few minutes late, glance down at my phone to see that I’m actually on time, and then she quickly notes, “I’m always early.”

When I arrive at award-winning chef Katie Button’s downtown Asheville restaurant, Cúrate, Dayna Reggero greets me with a hug before I even have the chance to properly introduce myself. I apologize for being a few minutes late, glance down at my phone to see that I’m actually on time, and then she quickly notes, “I’m always early.”

It’s hard to pinpoint if the 10-minute walk from my car to the restaurant, in the out of place 70-degree heat for October, is the reason why I feel so warm, or if it’s simply Reggero’s presence. She immediately begins telling me her favorite dishes, and as I look down at my menu, I notice someone has drawn stars beside certain items. She casually drops, “I had the waiter mark the dishes you could eat or ones they could at least make accessible for your dietary restrictions. That’s also why I came a few minutes early.” I think I’m able to identify that warm feeling now.

By trade, Reggero is an environmentalist. Her work spans over two decades and ranges from filmmaking to beginning her career as a spokesperson. However, her most skilled work might come in the form of organizing conversations, or simply starting them. Her most recent work, “The Climate Listening Project,” is a docu-series that has partnered with Moms Clean Air Force, National Audubon Society, Natural Resources Defense Council, Cultivating Resilience, Green Chalice and The Collider.

The series takes viewers to different communities within the United States, and as Reggero describes, “We’re not trying to convince anyone that climate change is real, we just want to show the real people impacted by climate change and the real people creating solutions.” And showing off real people is what she is all about. “I haven’t agreed to interviews in a long time. If I’m asked, I’m always certain there is someone better to connect with or someone who can provide exciting insight, so I tend to direct whomever requested an interview to them.”

Reggero’s journey to lending her voice and skills to change goes beyond connecting people. Her activism and eager spirit to bring awareness to issues has always been inside of her. After completing her undergraduate studies in communications at the University of West Florida and her Masters in applied science at the University of Denver, Reggero’s first job out of school was to help implement a triple bottom line greening for Fort Bragg communities in North Carolina with help from the Pentagon and U.S. Army. She found the connection between bettering the environment and helping a community long-term to be an equally exciting and rewarding opportunity. Reggero went on to promote clean energy with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign and helped Chimney Rock State Park become Green Certified by the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

A native of New York, Reggero found a sense of comfort and peace in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina and moved onto a large plot of land in the hills with her husband and Great Dane, Centaur. But while Reggero is nestled into her little piece of paradise, she’s well-traveled and well-versed in the way in which climate change is impacting communities near and far.

Her work with “The Climate Listening Project” features two women in Stokes County, N.C., who are using their local resources and their voices to fight against the harmful effects of coal ash and fracking. The project traveled as far as Belize to study the Wood Thrush bird, who spend their summers breeding and living in the eastern United States but migrate south and directly back to the east coast every year. The film recently took home a Best Short Documentary win at the 2017 Belize International Film Festival. Her other recent work has included launching Woody Harrelson’s Step Forward Paper in the United States and coordinating with Ian Somerhalder and the Ian Somerhalder Foundation during the “Years of Living Dangerously.”

“Connecting the science to the people is my ultimate goal,” she said. “If I can help accelerate the conversation in any way, I’ll feel like I’m doing something right.”

With the ever-growing number of women working in male-dominated fields such as film and science, Reggero is further evidence that you can show up and be the best person for the job and just happen to be female. “Every woman who succeeds where women haven’t succeeded before is a win, and I just want to keep that momentum going.”

As our lunch conversation concludes, my body temperature has returned to normal, but Reggero’s energy is at full speed. Her eagerness to continue connecting the dots for anyone and everyone is on full display, and even our waiter extends a formal greeting and thank you to her as we exit. As I return home and crack open my notes, I notice the word “cherish” has been written several times throughout the pages of dialogue I transcribed. And simply put, that has to be the best way to describe Reggero. She cherishes everyone, everything, and if you’re lucky enough to spend time with her, you too will cherish that.

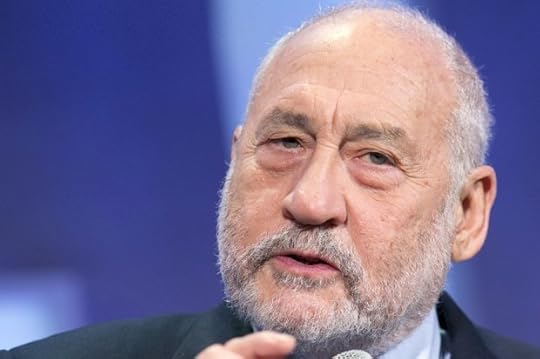

Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz warns of Bitcoin bubble

Joseph Stiglitz (Credit: AP/Mark Lennihan)

Less than 24 hours after trading at $10,000 per coin, Bitcoin continued its upward streak and surpassed $11,000 on Wednesday, while a Nobel Memorial Prize-winning economist sounded investor alarm bells over what may be a bubble waiting to burst.

In an interview on Bloomberg, economist Joseph Stiglitz was asked if Bitcoin, the best-known cryptocurrency, could be “viable” if it were regulated. Stiglitz pointed out that “one of the main functions of government is to create currency.” He explained that Bitcoin is “successful only because of its potential for circumvention, lack of oversight,” referencing the fact that, as a cryptocurrency, the distribution of Bitcoin is decentralized with no central bank to mint or manage the currency.

“It’s a bubble that’s going to give a lot of people a lot of exciting times as it rides up and then goes down,” Sitglitz told Bloomberg News.

He added, “so it seems to me it ought to be outlawed. It doesn’t serve any socially useful function.”

“The value of a Bitcoin today is expectations of what the Bitcoin is going to be tomorrow,” Stiglitz said.

But Stiglitz did argue that “the medium of exchange that we use for transaction” should be brought up to date. “Let’s move away from paper, into the 21st century of a digital economy,” he said.

Bitcoin has risen tenfold this year, the “largest gain of all asset classes,” according to The Guardian.

“The madness of crowds is well documented, but it is quite something to behold in the flesh. It’s hard to keep up with this – bitcoin just flew past the $11,000 mark, leaping $200 in barely five minutes before taking another big leg higher,” Neil Wilson, a senior market analyst at ETX Capital, told The Guardian.

Wilson added, “It’s up more than 14% today alone and the year-to-date chart is simply staggering. There are no fundamentals or technicals that explain this other than it being a massive speculative bubble.”

Though Bitcoin had an exchange rate of $11,150 per coin early in the day on Wednesday, in later trading today, Bitcoin spontaneously dipped 20% within the span of 6 hours.

Watch the interview with Stiglitz below: