Man Martin's Blog, page 227

April 25, 2011

Thoughts the Day After Easter

My sister Helen had a lovely idea about the Resurrection.

One time she had to board her dog Whitey at a kennel (this is all going to connect up, believe me). When she arrived days later to pick him up, he was so dejected, he couldn't even raise his head. He was lying in his crate, looking as if Helen's absence had taken the light out of the world: an impossible, nonsensical event that was too overwhelming to grasp for Whitey's doggy mind. He did not see Helen because he was too consumed by his own grief to see anything but floor. But when Helen spoke his name, "Whitey, I'm here for you," he jumped up suddenly reanimated by joy. She was here! She had come for him!

Anyone who has a beloved dog has had a similar experience.

Helen says that experience clarified one of the Gospel stories. According to one of the gospels, when Mary visits the tomb, she mistakes Jesus for a gardener, which seems ridiculous, until you realize like Whitey, Mary would have been so devastated by loss, she would have been able to see little more than the ground. It wasn't until he spoke to her, Mary realized. He was here! He had come for her!

Do I believe in the Resurrection? Well... Suffice to say, when I recite the Nicene Creed, I commit perjury about three times. But if faith is different from belief, if belief means I endorse this or that doctrine whereas faith means knowing that even though I cannot grasp it, all of this life - including the sickness, loss, and disappointment - and the good parts too - love, fulfillment, happiness - that all of that adds up to something, that it means something and has a purpose. And because the purpose cannot be discovered by any system of logic or rationality, then why shouldn't it be in one sense of the word, illogical, irrational. Why shouldn't it come from in a form that people would look at and say, "That couldn't have happened!" "That's impossible!"

That's the hope, the painful unquenchable hope. Not the Resurrection per se; it wouldn't have to be the Resurrection as far as I'm concerned. Just that, in my darkest hour, when unstoppable forces have crated me away for inexplicable purposes, and I have no will to raise my head, but can only let the floor, or the blanket or whatever it is, fill my sight because I also lack the will to close my eyes, that in that moment, the voice of someone I love and thought would never return will say, "I'm here."

One time she had to board her dog Whitey at a kennel (this is all going to connect up, believe me). When she arrived days later to pick him up, he was so dejected, he couldn't even raise his head. He was lying in his crate, looking as if Helen's absence had taken the light out of the world: an impossible, nonsensical event that was too overwhelming to grasp for Whitey's doggy mind. He did not see Helen because he was too consumed by his own grief to see anything but floor. But when Helen spoke his name, "Whitey, I'm here for you," he jumped up suddenly reanimated by joy. She was here! She had come for him!

Anyone who has a beloved dog has had a similar experience.

Helen says that experience clarified one of the Gospel stories. According to one of the gospels, when Mary visits the tomb, she mistakes Jesus for a gardener, which seems ridiculous, until you realize like Whitey, Mary would have been so devastated by loss, she would have been able to see little more than the ground. It wasn't until he spoke to her, Mary realized. He was here! He had come for her!

Do I believe in the Resurrection? Well... Suffice to say, when I recite the Nicene Creed, I commit perjury about three times. But if faith is different from belief, if belief means I endorse this or that doctrine whereas faith means knowing that even though I cannot grasp it, all of this life - including the sickness, loss, and disappointment - and the good parts too - love, fulfillment, happiness - that all of that adds up to something, that it means something and has a purpose. And because the purpose cannot be discovered by any system of logic or rationality, then why shouldn't it be in one sense of the word, illogical, irrational. Why shouldn't it come from in a form that people would look at and say, "That couldn't have happened!" "That's impossible!"

That's the hope, the painful unquenchable hope. Not the Resurrection per se; it wouldn't have to be the Resurrection as far as I'm concerned. Just that, in my darkest hour, when unstoppable forces have crated me away for inexplicable purposes, and I have no will to raise my head, but can only let the floor, or the blanket or whatever it is, fill my sight because I also lack the will to close my eyes, that in that moment, the voice of someone I love and thought would never return will say, "I'm here."

Published on April 25, 2011 03:21

April 24, 2011

Writing Craft/Aristotle Part Two

Just when you thought it was safe to go back into cyberspace, here comes Martin bloviating on about Aristotle. Dang Aristotle's like a loose tooth; once you discover it, you can't leave it alone.

Aristotle had one more thing to say about the requirements for a good tragedy that I think is worth noting. Just one more thing, I swear, and then if I mention Aristotle again, you can come over to my house and slap me.

Aristotle also said that plays had to be of a certain magnitude.

What he meant by that was they had to cover a certain segment of human experience - not too much and not too little. This is where the famous dramatic unities - time, place, and action - rear their ugly heads, although Aristotle himself never articulated them in that fashion.

Aristotle's idea is you can't successfully tell a story about Prometheus chained to a rock - Euripides did just that, but Aristotle's point is he maybe shouldn't have bothered - because the magnitude, the scope, is too short. It's a single incident and doesn't make a story. Nor can you tell the entire life of Agamemnon, there are just too many incidents, loose ends, and parts that don't fit.

Again, if Aristotle's right in this, and for me at least he is, he is telling us less about the nature of tragedy than about our own ability to receive and make meaning. We can only find meaningful narrative within certain parameters

It reminds me of what Bertrand Russell said about grasping the Theory of Relativity. He said that if we were much, much smaller - so small we could physically witness the movements of atoms - or much, much larger so that we could watch the swirl and spread of galaxies, Relativity would be intuitively obvious to us. It's only being the size we are, stuck in the middle ground of scale where objects seem so obdurately solid, distance seems so fixed, and time has a metronomic consistency, that Relativity strikes us as counter-intuitive.

Thus it is with stories; I - and this is both humbling and chilling - cannot make meaning of an entire lifetime. "The meaning of life is that it ends," says Kafka, which is about as much as any of us can deduce. Oh, I can shape a life, or even several lifetimes, into a story, but life itself - the complexities, oddities, and the ultimate mysterious termination - is just too much for me to grasp. The magnitude is just too great. If I'm going to make sense of it, it's going to have to be served to me in smaller slices.

Maybe on the small end of magnitude, where again I cannot make meaning, there are others who can fare better. This young generation, consarn 'em with their twitterweets and their interwebs and their cellpods and their i-dangles, have grown up watching a zillion channels at once; they watch a few seconds of one narrative - in which I include commercials - press a button, and watch a few seconds of something else. Maybe this fractured story telling provides meaning to a mind trained to receive it that way, but not to me. But I still say, no one, no one, can make meaning of a life entire, there's just too much stuff. Our eyes are not large enough to see the big picture.

Aristotle had one more thing to say about the requirements for a good tragedy that I think is worth noting. Just one more thing, I swear, and then if I mention Aristotle again, you can come over to my house and slap me.

Aristotle also said that plays had to be of a certain magnitude.

What he meant by that was they had to cover a certain segment of human experience - not too much and not too little. This is where the famous dramatic unities - time, place, and action - rear their ugly heads, although Aristotle himself never articulated them in that fashion.

Aristotle's idea is you can't successfully tell a story about Prometheus chained to a rock - Euripides did just that, but Aristotle's point is he maybe shouldn't have bothered - because the magnitude, the scope, is too short. It's a single incident and doesn't make a story. Nor can you tell the entire life of Agamemnon, there are just too many incidents, loose ends, and parts that don't fit.

Again, if Aristotle's right in this, and for me at least he is, he is telling us less about the nature of tragedy than about our own ability to receive and make meaning. We can only find meaningful narrative within certain parameters

It reminds me of what Bertrand Russell said about grasping the Theory of Relativity. He said that if we were much, much smaller - so small we could physically witness the movements of atoms - or much, much larger so that we could watch the swirl and spread of galaxies, Relativity would be intuitively obvious to us. It's only being the size we are, stuck in the middle ground of scale where objects seem so obdurately solid, distance seems so fixed, and time has a metronomic consistency, that Relativity strikes us as counter-intuitive.

Thus it is with stories; I - and this is both humbling and chilling - cannot make meaning of an entire lifetime. "The meaning of life is that it ends," says Kafka, which is about as much as any of us can deduce. Oh, I can shape a life, or even several lifetimes, into a story, but life itself - the complexities, oddities, and the ultimate mysterious termination - is just too much for me to grasp. The magnitude is just too great. If I'm going to make sense of it, it's going to have to be served to me in smaller slices.

Maybe on the small end of magnitude, where again I cannot make meaning, there are others who can fare better. This young generation, consarn 'em with their twitterweets and their interwebs and their cellpods and their i-dangles, have grown up watching a zillion channels at once; they watch a few seconds of one narrative - in which I include commercials - press a button, and watch a few seconds of something else. Maybe this fractured story telling provides meaning to a mind trained to receive it that way, but not to me. But I still say, no one, no one, can make meaning of a life entire, there's just too much stuff. Our eyes are not large enough to see the big picture.

Published on April 24, 2011 04:16

April 23, 2011

What Do Essays on the Writing Craft Teach Us About Ourselves

The shelves of your local bookstore are littered with books of advice for would-be writers, making it impossible to discuss craft essays in general. So I'm going to zoom in on one particular craft book - the grandaddy of all craft books - Aristotle's Poetics.

There are lots of things we have to keep in mind with Aristotle. For openers, he never intended to write a craft book; as in so many other fields of knowledge he appears just to be laying down taxonomies and general principles. And his legacy is, let us say, spotty. In the field of dentistry, he helpfully tells us women have fewer teeth than men. In natural science, he informs us that snakes have no legs because their bodies are too long. All vertebrates, he points out, have two legs, four legs, or none. Since snakes' bodies are too long to be supported by two or four legs, they have no legs at all. (Actually, that last part makes a weird kind of sense.)

Lastly, Aristotle was only writing about one very narrow genre: tragedies, not even full-length plays, but one-acts he would have seen performed at the Theater of Dionysus. Aristotle had never seen a novel, short story, or movie. There were no video games in Aristotle's day. If there had been, he wouldn't have had time to come up with the thing about the snakes.

Having said all this, and made this lengthy preamble of caveats and disclaimers, I'm only going to look at one little bit of what Aristotle had to say.

He writes that tragedy is an "imitation of an action, that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude." The need for seriousness, when it comes to tragedy, goes without saying, which is probably why Aristotle felt called upon to say it. Writing a silly tragedy is out of the question. It's just too ambitious. Life itself is a silly tragedy.

The part about imitating an action is more key. What Aristotle meant by imitation of an action primarily had to do with "Perepetia" or Reversal of the Situation and a scene of Recognition. When it comes to aesthetics, Aristotle is on entirely different ground than with the natural sciences. Is isn't like pointing out snakes don't have legs; there are plays, plenty of them, that Aristotle says lack this all-important reversal and recognition. He doesn't claim that tragedies must contain these elements, but that they ought to. It would be as if living in a world where some snakes had no legs, some had two, and some had twelve, Aristotle said that the best kind of snake had no legs. Best under what criteria?

When Aristotle says the greatest tragedies have Reversal and Recognition, he means these are the best tragedies to him, and to the audience as far as he can tell. Even if Aristotle's tastes in this regard aren't universal and even if we cannot say they are to be preferred over other criteria, to the extent we share them - and personally, I share them whole hog - they tell us a great deal about ourselves.

We are interested in seeing stories where things change, and no amount of "characterization" can make up for a static plot line. In the case of tragedy, we like seeing things start out more or less hunky-dory and then go all kaflooey. (In comedy, although Aristotle does not deal with this, presumably we like to see things go from being totally screwed up to finally being screwed down again.) This need for temporality, for mutability and reversal is an interesting aspect of our nature. There's a Gahan Wilson cartoon of two bored-looking angels standing around in heaven, and one of them says, "I keep thinking it's Wednesday." That's the thing about us; we bitch if things go bad, but what we really can't stand is if they stay the same. I prefer a life with a certain degree of friction, failure, and frustration than an unbroken tableau of contentment.

Aristotle's dictum that the action be "complete" is intriguing too. Aristotle seems to be the first person to articulate that stories need a beginning, middle, and end. I agree with Aristotle's formulation, but how odd that we should have a taste for that. Where did we acquire it? What in our lives has ever occurred in such neat segments? Isn't life always a matter of vague "middles" without clear beginnings or definite ends? Oh, I know humans have plenty of beginnings and ends - birthdays, weddings, graduations, retirement parties, funerals - but most of these, when you think of it, are man-made contrivances. Nothing in Nature knows what "New Year's Day" means. These demarcations are as arbitrary, and strangely essential to our sense of well-being, as a five-act play with an intermission.

The Scene of Recognition is an interesting stipulation also. It's not enough for Oedipus to get bludgeoned by fate, he has to come to an understanding of what has happened and why, and more specifically, his own unknowing role in it. This is another anomaly that surely points to another desire that life does not fulfill. How often have we ever been lucky enough to understand why crap happens to us? Isn't it more the case that things rain down on us from space with no clear reason: old age, illness, death, loss? That these things are predictable and unavoidable makes them no less mysterious. Oedipus at least gets to say, "I screwed my mother! That's what went wrong! There was a curse! The gods had it in for me!" The rest of us, waiting for the day we'll see the spot on the X-Ray that will be the thing that kills us, waiting for the phone call that someone we love has died, waiting for the tsunami, the wildfire, the terrorist - the rest of us will have no such moment. We will live our lives as well as we can in the meantime, but that fell blade will fall, and when it does so, it will strike with astonishing abruptness and without explanation. Maybe this is why Oedipus can pull out his eyes. Once he has seen the thread that tied himself to his fate, he had already seen what the rest of us will spend our whole lives looking for.

Man. I got unexpectedly grim there at the end, didn't I?

Maybe another post, I'll talk some more about Aristotle, but I'll leave him alone for now.

Meanwhile, why don't you think about how come snakes don't have legs?

There are lots of things we have to keep in mind with Aristotle. For openers, he never intended to write a craft book; as in so many other fields of knowledge he appears just to be laying down taxonomies and general principles. And his legacy is, let us say, spotty. In the field of dentistry, he helpfully tells us women have fewer teeth than men. In natural science, he informs us that snakes have no legs because their bodies are too long. All vertebrates, he points out, have two legs, four legs, or none. Since snakes' bodies are too long to be supported by two or four legs, they have no legs at all. (Actually, that last part makes a weird kind of sense.)

Lastly, Aristotle was only writing about one very narrow genre: tragedies, not even full-length plays, but one-acts he would have seen performed at the Theater of Dionysus. Aristotle had never seen a novel, short story, or movie. There were no video games in Aristotle's day. If there had been, he wouldn't have had time to come up with the thing about the snakes.

Having said all this, and made this lengthy preamble of caveats and disclaimers, I'm only going to look at one little bit of what Aristotle had to say.

He writes that tragedy is an "imitation of an action, that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude." The need for seriousness, when it comes to tragedy, goes without saying, which is probably why Aristotle felt called upon to say it. Writing a silly tragedy is out of the question. It's just too ambitious. Life itself is a silly tragedy.

The part about imitating an action is more key. What Aristotle meant by imitation of an action primarily had to do with "Perepetia" or Reversal of the Situation and a scene of Recognition. When it comes to aesthetics, Aristotle is on entirely different ground than with the natural sciences. Is isn't like pointing out snakes don't have legs; there are plays, plenty of them, that Aristotle says lack this all-important reversal and recognition. He doesn't claim that tragedies must contain these elements, but that they ought to. It would be as if living in a world where some snakes had no legs, some had two, and some had twelve, Aristotle said that the best kind of snake had no legs. Best under what criteria?

When Aristotle says the greatest tragedies have Reversal and Recognition, he means these are the best tragedies to him, and to the audience as far as he can tell. Even if Aristotle's tastes in this regard aren't universal and even if we cannot say they are to be preferred over other criteria, to the extent we share them - and personally, I share them whole hog - they tell us a great deal about ourselves.

We are interested in seeing stories where things change, and no amount of "characterization" can make up for a static plot line. In the case of tragedy, we like seeing things start out more or less hunky-dory and then go all kaflooey. (In comedy, although Aristotle does not deal with this, presumably we like to see things go from being totally screwed up to finally being screwed down again.) This need for temporality, for mutability and reversal is an interesting aspect of our nature. There's a Gahan Wilson cartoon of two bored-looking angels standing around in heaven, and one of them says, "I keep thinking it's Wednesday." That's the thing about us; we bitch if things go bad, but what we really can't stand is if they stay the same. I prefer a life with a certain degree of friction, failure, and frustration than an unbroken tableau of contentment.

Aristotle's dictum that the action be "complete" is intriguing too. Aristotle seems to be the first person to articulate that stories need a beginning, middle, and end. I agree with Aristotle's formulation, but how odd that we should have a taste for that. Where did we acquire it? What in our lives has ever occurred in such neat segments? Isn't life always a matter of vague "middles" without clear beginnings or definite ends? Oh, I know humans have plenty of beginnings and ends - birthdays, weddings, graduations, retirement parties, funerals - but most of these, when you think of it, are man-made contrivances. Nothing in Nature knows what "New Year's Day" means. These demarcations are as arbitrary, and strangely essential to our sense of well-being, as a five-act play with an intermission.

The Scene of Recognition is an interesting stipulation also. It's not enough for Oedipus to get bludgeoned by fate, he has to come to an understanding of what has happened and why, and more specifically, his own unknowing role in it. This is another anomaly that surely points to another desire that life does not fulfill. How often have we ever been lucky enough to understand why crap happens to us? Isn't it more the case that things rain down on us from space with no clear reason: old age, illness, death, loss? That these things are predictable and unavoidable makes them no less mysterious. Oedipus at least gets to say, "I screwed my mother! That's what went wrong! There was a curse! The gods had it in for me!" The rest of us, waiting for the day we'll see the spot on the X-Ray that will be the thing that kills us, waiting for the phone call that someone we love has died, waiting for the tsunami, the wildfire, the terrorist - the rest of us will have no such moment. We will live our lives as well as we can in the meantime, but that fell blade will fall, and when it does so, it will strike with astonishing abruptness and without explanation. Maybe this is why Oedipus can pull out his eyes. Once he has seen the thread that tied himself to his fate, he had already seen what the rest of us will spend our whole lives looking for.

Man. I got unexpectedly grim there at the end, didn't I?

Maybe another post, I'll talk some more about Aristotle, but I'll leave him alone for now.

Meanwhile, why don't you think about how come snakes don't have legs?

Published on April 23, 2011 08:02

April 22, 2011

Booklist Raves Over Paradise Dogs

Paradise Dogs got a terrific review from Booklist. I've never met Elizabeth Dickie, but she clearly knows great literature when she sees it.

Adam Newman has a knack for making things happen in 1960s Florida. He wooed and won Evelyn while selling her a house. With her he created Paradise Dogs, a legendary hot-dog stand where they made a fortune before selling out. Adam can also assume others' identities, successfully delivering babies and saving others' marriages. Unfortunately, he can't save his own, or find the bag of diamonds he borrowed, or stop the drinking that keeps him in a blurry muddle most of the time. One thing he is clear on is that shadowy forces are buying up huge chunks of land around his plots in Orange County. Suspecting a revitalization of the Cross Florida Barge Canal, he tries to uncover the people behind the scheme while staying ahead of the owners of the diamonds and the men in the white jackets. In this raucous novel, Adam is a lovably infuriating character in a cast of originals, including Walt Disney. The pacing is perfect, the tone is the right blend of picaresque and touching. Man Martin is simply brilliant.

— Elizabeth Dickie

Adam Newman has a knack for making things happen in 1960s Florida. He wooed and won Evelyn while selling her a house. With her he created Paradise Dogs, a legendary hot-dog stand where they made a fortune before selling out. Adam can also assume others' identities, successfully delivering babies and saving others' marriages. Unfortunately, he can't save his own, or find the bag of diamonds he borrowed, or stop the drinking that keeps him in a blurry muddle most of the time. One thing he is clear on is that shadowy forces are buying up huge chunks of land around his plots in Orange County. Suspecting a revitalization of the Cross Florida Barge Canal, he tries to uncover the people behind the scheme while staying ahead of the owners of the diamonds and the men in the white jackets. In this raucous novel, Adam is a lovably infuriating character in a cast of originals, including Walt Disney. The pacing is perfect, the tone is the right blend of picaresque and touching. Man Martin is simply brilliant.

— Elizabeth Dickie

Published on April 22, 2011 02:57

April 21, 2011

Schliemann and Agamemnon

Stepping into the National Archeological Museum in Athens, the first thing you see is the Mycenae gallery. (Actually the first thing we saw was a large tortoise roaming the area outside the bathrooms. After getting a picture, I notified a docent, who shrugged, laughed and indicated the turtle was a frequent and not unwelcome patron.)

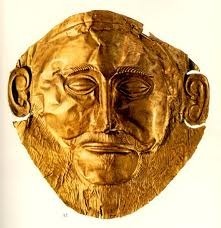

The first thing you see stepping into the Mycenae gallery is the mask of Agamemnon. (A quick thumbnail refresher: the earlier Minoan civilization was wiped out by the Myceneans - called the Acheans by Homer - and the legendary king of the Myceneans was Agamemnon, who sacrificed his daughter to Poseidon, fought at Troy, was murdered by his wife and was avenged by his son.) And the burial mask of the star of this maelstrom - Agamemnon - gazes calmly at us through beaten gold.

Or at least it's supposed to be Agamemnon.

In 1876, when most scholars assumed the Illiad had all the factual basis of the Great Pumpkin, a retired German businessman in the Import-Export trade, put egg on everyone's face by sticking a shovel into the dirt in the place Homer declared Agamemnon had ruled. The intellectual elite were laughing up their sleeves at this. It was like looking for Cinderella's castle or the mine where the seven dwarves worked.

But then, just where Homer said, Schliemann began to unearth gold. Gold of unbelievably beautful workmanship.

With the touching modesty and self-effacement so common to German import-exporters, Schliemann notified the Greek King: "With great joy I announce to Your Majesty that I have discovered the tombs which the tradition proclaimed by Pausanias indicates to be the graves of Agamemnon, Cassandra, Eurymedon and their companions, all slain at a banquet by Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthos." He also said the finds would create the greatest museum on earth.In little time, the know-it-all archeologists were laughing at Schliemann again. The graves at Mycenae were too late by hundreds of years to have belonged to Agamemnon. Now in its display case, "Mask of Agamemnon" has quotation marks around it. It turns out, if you get egg on your face, it washes off pretty easily.Well, I don't care. As far as I'm concerned, that is the mask of Agamemnon, right down to the whiskers. Him what digs it up gets to name it. Them's my rules.Agamemnon, who slew his daughter, sailed the wine-dark sea to bring down the mighty walls of Troy. He who returned with a new concubine, Cassandra, good in bed but so boring. His whose wife killed him for the daughter, the concubine, and because she'd taken a lover herself, so what the hey. That is Agamemnon, whom Orestes avenged. Agamemnon of Homer and Sophocles. Someone put a gold mask on him. No one mentioned that part, but it's Agamemnon nonetheless.

With the touching modesty and self-effacement so common to German import-exporters, Schliemann notified the Greek King: "With great joy I announce to Your Majesty that I have discovered the tombs which the tradition proclaimed by Pausanias indicates to be the graves of Agamemnon, Cassandra, Eurymedon and their companions, all slain at a banquet by Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthos." He also said the finds would create the greatest museum on earth.In little time, the know-it-all archeologists were laughing at Schliemann again. The graves at Mycenae were too late by hundreds of years to have belonged to Agamemnon. Now in its display case, "Mask of Agamemnon" has quotation marks around it. It turns out, if you get egg on your face, it washes off pretty easily.Well, I don't care. As far as I'm concerned, that is the mask of Agamemnon, right down to the whiskers. Him what digs it up gets to name it. Them's my rules.Agamemnon, who slew his daughter, sailed the wine-dark sea to bring down the mighty walls of Troy. He who returned with a new concubine, Cassandra, good in bed but so boring. His whose wife killed him for the daughter, the concubine, and because she'd taken a lover herself, so what the hey. That is Agamemnon, whom Orestes avenged. Agamemnon of Homer and Sophocles. Someone put a gold mask on him. No one mentioned that part, but it's Agamemnon nonetheless.

The first thing you see stepping into the Mycenae gallery is the mask of Agamemnon. (A quick thumbnail refresher: the earlier Minoan civilization was wiped out by the Myceneans - called the Acheans by Homer - and the legendary king of the Myceneans was Agamemnon, who sacrificed his daughter to Poseidon, fought at Troy, was murdered by his wife and was avenged by his son.) And the burial mask of the star of this maelstrom - Agamemnon - gazes calmly at us through beaten gold.

Or at least it's supposed to be Agamemnon.

In 1876, when most scholars assumed the Illiad had all the factual basis of the Great Pumpkin, a retired German businessman in the Import-Export trade, put egg on everyone's face by sticking a shovel into the dirt in the place Homer declared Agamemnon had ruled. The intellectual elite were laughing up their sleeves at this. It was like looking for Cinderella's castle or the mine where the seven dwarves worked.

But then, just where Homer said, Schliemann began to unearth gold. Gold of unbelievably beautful workmanship.

With the touching modesty and self-effacement so common to German import-exporters, Schliemann notified the Greek King: "With great joy I announce to Your Majesty that I have discovered the tombs which the tradition proclaimed by Pausanias indicates to be the graves of Agamemnon, Cassandra, Eurymedon and their companions, all slain at a banquet by Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthos." He also said the finds would create the greatest museum on earth.In little time, the know-it-all archeologists were laughing at Schliemann again. The graves at Mycenae were too late by hundreds of years to have belonged to Agamemnon. Now in its display case, "Mask of Agamemnon" has quotation marks around it. It turns out, if you get egg on your face, it washes off pretty easily.Well, I don't care. As far as I'm concerned, that is the mask of Agamemnon, right down to the whiskers. Him what digs it up gets to name it. Them's my rules.Agamemnon, who slew his daughter, sailed the wine-dark sea to bring down the mighty walls of Troy. He who returned with a new concubine, Cassandra, good in bed but so boring. His whose wife killed him for the daughter, the concubine, and because she'd taken a lover herself, so what the hey. That is Agamemnon, whom Orestes avenged. Agamemnon of Homer and Sophocles. Someone put a gold mask on him. No one mentioned that part, but it's Agamemnon nonetheless.

With the touching modesty and self-effacement so common to German import-exporters, Schliemann notified the Greek King: "With great joy I announce to Your Majesty that I have discovered the tombs which the tradition proclaimed by Pausanias indicates to be the graves of Agamemnon, Cassandra, Eurymedon and their companions, all slain at a banquet by Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthos." He also said the finds would create the greatest museum on earth.In little time, the know-it-all archeologists were laughing at Schliemann again. The graves at Mycenae were too late by hundreds of years to have belonged to Agamemnon. Now in its display case, "Mask of Agamemnon" has quotation marks around it. It turns out, if you get egg on your face, it washes off pretty easily.Well, I don't care. As far as I'm concerned, that is the mask of Agamemnon, right down to the whiskers. Him what digs it up gets to name it. Them's my rules.Agamemnon, who slew his daughter, sailed the wine-dark sea to bring down the mighty walls of Troy. He who returned with a new concubine, Cassandra, good in bed but so boring. His whose wife killed him for the daughter, the concubine, and because she'd taken a lover herself, so what the hey. That is Agamemnon, whom Orestes avenged. Agamemnon of Homer and Sophocles. Someone put a gold mask on him. No one mentioned that part, but it's Agamemnon nonetheless.

Published on April 21, 2011 02:48

April 20, 2011

Knossos

Knossos.

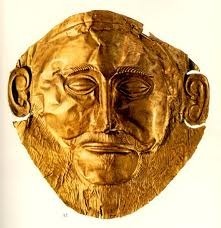

Knossos. An enigma inside a puzzle wrapped in a mystery shrouded in tourism.Sir Arthur Evans, bless his heart, in his heavy handed attempts to preserve a site that predates the Golden Age of Greece by 1200 years, brought in cement mixers and Sherwin Williams paint and tarted the place up as he imagined it must've looked three millenia ago.

An enigma inside a puzzle wrapped in a mystery shrouded in tourism.Sir Arthur Evans, bless his heart, in his heavy handed attempts to preserve a site that predates the Golden Age of Greece by 1200 years, brought in cement mixers and Sherwin Williams paint and tarted the place up as he imagined it must've looked three millenia ago.

Still. Owing to him we have insights into a remarkable culture that had impressive art and architecture and a written language we may never decipher. Standing before the famous fresco of a boy sommersaulting over the back of a bull, you think, "This is it! Surely this is it! The Palace of Minos, and surely this bull-dancing is the inspiration for the Minotaur!" Some Greek mythographer did to the Minoans what Arthur Evans was to do again in another few thousand years - take an alien culture, shuffle the pieces around, repaint them, pour in concrete to fill in the gaps, and interpretted it after his own liking.But you look at the frescoes and you know - you just know - that whatever misinterpretations

Still. Owing to him we have insights into a remarkable culture that had impressive art and architecture and a written language we may never decipher. Standing before the famous fresco of a boy sommersaulting over the back of a bull, you think, "This is it! Surely this is it! The Palace of Minos, and surely this bull-dancing is the inspiration for the Minotaur!" Some Greek mythographer did to the Minoans what Arthur Evans was to do again in another few thousand years - take an alien culture, shuffle the pieces around, repaint them, pour in concrete to fill in the gaps, and interpretted it after his own liking.But you look at the frescoes and you know - you just know - that whatever misinterpretations

intrude, that these were people who had music, poetry, and song. Unlike the more sanguine artwork of the later Hellenistic culture, here there are no pictures of Zeus off to rape Metis, Zeus off to rape Ledo, Zeus off to rape Ganymede or Europa or whomever, just happy women, monkeys, playful octopi, and a smiling youth doing a sommersault over a bull's back.

intrude, that these were people who had music, poetry, and song. Unlike the more sanguine artwork of the later Hellenistic culture, here there are no pictures of Zeus off to rape Metis, Zeus off to rape Ledo, Zeus off to rape Ganymede or Europa or whomever, just happy women, monkeys, playful octopi, and a smiling youth doing a sommersault over a bull's back.

Published on April 20, 2011 02:40

April 19, 2011

Cameras

Nancy mislaid her camera and a shadow fell over our trip until she got it back from the shop where she'd left it.

Nancy mislaid her camera and a shadow fell over our trip until she got it back from the shop where she'd left it."I was in here yesterday," she began, "and-"

"Yes," said the shopkeeper in playful admonishment, "and you left your cah-mare-ah," holding it up by its strap like a mouse.

Not losing something is best, but there is delight in losing it and then having it restored - especially by a droll shopkeeper. (Incidentally, all the shopkeepers here are droll. It's part of their licensing requirements.) I was particularly happy to see Nancy's camera again; it had all the pictures of me.

Of all the foolish things tourists do, the foolishest is probably our incessant picture taking. Surely memories should be enough, right? Besides, photos never quite do what I want them to do. I can get a picture of the snowpeaks above the old bay and the multicolored buildings with their red tile roofs - but I can't in the picture the sense of "I'm here now! This is me right now in this place!" I can take a picture of vineyards stretching in patchwork down the Cretan mountainside, but never get the tinkling sound of bells from a nearby herd of sheep. I don't have a camera with me to catch the beauty of the rain-splashed cobbles of Hania. I see a cat stalking something on the red tile roof across from our room, and take a picture, but I'm not zoomed in far enough, and before I can take another, she's gone.But still - what else can I do? Sometimes there's just too much beauty for two eyes to hold, so I start taking pictures.Don't forget your cah-mare-ah.

Of all the foolish things tourists do, the foolishest is probably our incessant picture taking. Surely memories should be enough, right? Besides, photos never quite do what I want them to do. I can get a picture of the snowpeaks above the old bay and the multicolored buildings with their red tile roofs - but I can't in the picture the sense of "I'm here now! This is me right now in this place!" I can take a picture of vineyards stretching in patchwork down the Cretan mountainside, but never get the tinkling sound of bells from a nearby herd of sheep. I don't have a camera with me to catch the beauty of the rain-splashed cobbles of Hania. I see a cat stalking something on the red tile roof across from our room, and take a picture, but I'm not zoomed in far enough, and before I can take another, she's gone.But still - what else can I do? Sometimes there's just too much beauty for two eyes to hold, so I start taking pictures.Don't forget your cah-mare-ah.

Published on April 19, 2011 03:39

April 18, 2011

My New American Life Review

In the final scene our heroine, who cannot drive, is stuck in traffic in an almost certainly stolen SUV, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, leaving behind a home where she cannot stay, but where they aren't ready for her to leave, towards an apartment where she'll be able to stay - at most - a few months.

In the final scene our heroine, who cannot drive, is stuck in traffic in an almost certainly stolen SUV, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, leaving behind a home where she cannot stay, but where they aren't ready for her to leave, towards an apartment where she'll be able to stay - at most - a few months.Lula is an Albanian emigre during the presidency of Bush the Younger post 911, precisely at the time when America was at its most xenophobic. After working illegally as a waitress she lands work as a part time nanny to the teenage son of an investment banker abandonned by his mentally ill wife. Things seem to be going well - or as well as Lula could hope - when three of her countrymen show up and ask her to hold onto a gun for them.

An immigrant perspective on the United States provides an ideal satiric vantage point, as writers have long known. Prose supplies a nice additional touch by making Lula herself a story teller. At the behest of her employer and the lawyer who's working to secure her a greencard - two liberals of the sort naively eager to hear tales of hardship - Lula writes "true stories" of Albania, fabricated patchworks of history and fairytale. It's the sort of thing that happens everyday to people of all ethnicities asked to "perform" their identities. Lula spins out improbable accounts in writing as well as conversation, withholding the real but equally improbable truth.

The novel is funny, charming, and well-written, and Prose keeps us dangling at the edges of things that don't quite happen: affairs that don't quite come off, dysfunctional families that manage to stay on just this side of functionality, guns the fire, but not fatally. And truth to tell, the experience is at times frustrating for the reader - I found myself longing for something more, something richer, something greater at stake, but then at the end - unaccountably, to me - the novel comes together in an entirely fulfilling way. In the last scene of Lula driving across a bridge, I realized that Prose's formless story catches the essence a New American Life, of American Life, and maybe Life in General: hopping from stone to stone, always unfinished, always provisional, making it up as we go along.

Published on April 18, 2011 02:56

April 17, 2011

Getting Lost in Crete

People who know me will wonder how much longer I could forebear before posting another blog on the topic of getting lost, but this time, I swear it's not my fault.

Nancy and I rented a motorcar to get around Crete (For some reason, on Crete, I always thought of it as a motorcar.) On the major roads we were fine. The phrase "hunky-dory" springs to the lips. But on the local streets -! It's a good job we hadn't bought one of those ornamental knives for sale in Crete, or I'm not sure I could have answered for our safe return.

To start with, the roads in Crete are laid out in a manner that is, in the truest and deepest sense of the word, Cretinous. Hania, where we stayed, is filled with quaint alleys and narrow crooked lanes of picturesque charm. Except when driving, you don't want quaint, charming, or picturesque. You want clearly posted directions and a reasonable degree of width. Hania was built in the 17th Century by Venetians. That should tell you something right there. Do they even have roads in Venice? I thought it was all canals. And these Venetians were 17th Century Venetians. My glass of ouzo shakes at the thought.

Secondly, the street signs, what there are of them, are posted for the convenience of pedestrians not motorists. Even craning the head out of a window so far that passing trucks threaten to take it off, it's impossible to make out the 48-point white lettering on a blue sign affixed to the side of a buiding.

As if the maze of zig-zagging, unnamed, one-way streets weren't bad enough, the folks who helpfully transliterated the Greek names into English felt a happy freedom from any need to arrive at a consensus, so that Hania, to give one example, is sometimes rendered Chania, Cania, Kania, and Xania. Confound this by a Greek alphabet in which the "R" sound is represented by "P," and "S" by something that looks like an "E" and you'll have some idea of what we were up against.

Finally, having escaped the environs of Hania, Nancy and I arrived on a major road, where, as I have told you, we were fine. We were on our way to Knossos on the eastern side of the island. As we drove that beautiful landscape, the green mountain rising on one shoulder, and on the other, the hills sloping down to the seashore dotted with Mediterranean villas, I regaled Nancy with the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, the original basis of which, was the palace of Knossos itself. As you will recall, the Minotaur was really the lesser of the two perils Theseus faced, a garden-variety composite monster, easily dispatched with quick reflexes and a sword. The greater peril - and here a shudder of recognition passed over me - was the twists and turns, winding nameless passages and dead ends, of the labyrinth.

Nancy and I rented a motorcar to get around Crete (For some reason, on Crete, I always thought of it as a motorcar.) On the major roads we were fine. The phrase "hunky-dory" springs to the lips. But on the local streets -! It's a good job we hadn't bought one of those ornamental knives for sale in Crete, or I'm not sure I could have answered for our safe return.

To start with, the roads in Crete are laid out in a manner that is, in the truest and deepest sense of the word, Cretinous. Hania, where we stayed, is filled with quaint alleys and narrow crooked lanes of picturesque charm. Except when driving, you don't want quaint, charming, or picturesque. You want clearly posted directions and a reasonable degree of width. Hania was built in the 17th Century by Venetians. That should tell you something right there. Do they even have roads in Venice? I thought it was all canals. And these Venetians were 17th Century Venetians. My glass of ouzo shakes at the thought.

Secondly, the street signs, what there are of them, are posted for the convenience of pedestrians not motorists. Even craning the head out of a window so far that passing trucks threaten to take it off, it's impossible to make out the 48-point white lettering on a blue sign affixed to the side of a buiding.

As if the maze of zig-zagging, unnamed, one-way streets weren't bad enough, the folks who helpfully transliterated the Greek names into English felt a happy freedom from any need to arrive at a consensus, so that Hania, to give one example, is sometimes rendered Chania, Cania, Kania, and Xania. Confound this by a Greek alphabet in which the "R" sound is represented by "P," and "S" by something that looks like an "E" and you'll have some idea of what we were up against.

Finally, having escaped the environs of Hania, Nancy and I arrived on a major road, where, as I have told you, we were fine. We were on our way to Knossos on the eastern side of the island. As we drove that beautiful landscape, the green mountain rising on one shoulder, and on the other, the hills sloping down to the seashore dotted with Mediterranean villas, I regaled Nancy with the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, the original basis of which, was the palace of Knossos itself. As you will recall, the Minotaur was really the lesser of the two perils Theseus faced, a garden-variety composite monster, easily dispatched with quick reflexes and a sword. The greater peril - and here a shudder of recognition passed over me - was the twists and turns, winding nameless passages and dead ends, of the labyrinth.

Published on April 17, 2011 03:47

April 16, 2011

Thoughts While Flying Across the Aegean

Flying across the Aegean from Athens to Crete, the sun was rising and the only way to distinguish the sea from the sky beyond it was the band of sunlight stretching over the water.

This was the sea Theseus crossed to kill the Minotaur, and returned - partway - with the Princess Ariadne who'd - predictably - fallen in love with him, agreeing to betray country and family. (The Minotaur was her half-brother by Queen Pasiphae and a sacred bull. It's complicated.)

Theseus stopped on an island, and Dionysius, falling in love with Ariadne, took her for his own. At least that's what Theseus claimed. Theseus was a big one for claiming things weren't his doing whenever they worked out to his advantage. He said the thing with the sails wasn't his doing either. Before sailing, he'd promised his father, King Aegeas, to raise white sails if he returned safely; otherwise the sails wouldbe black. When Aegeas saw the black sails on the horizon, he leapt to his death in despair, throwing himself into the sea that still bears his name, the Aegean.

Theseus said it was all a big misunderstanding, that he'd been asleep below decks and hadn't thought to tell the crew about the sails; what with killing the Minotaur, escaping Minos, and meeting Dionysisus, it had slipped his mind. These things happen. Of course, it did mean Theseus was now king, but you really can't hold him responsible. In a later episode of the same story, Daedelus and Icarus flew over this sea on their wax and feather wings. Only Daedelus made it. Flying from Crete to Sicily, they'd have been on a sharp diagonal course under my plane. "I just flew in from the coast, and, boy, are my arms tired!" is what Daedelus said when the King of Sicily welcomed him, only in those days it wasn't a joke, but just a statement of fact.

Jason sailed this patch of sea, too, although Odysseus only did so on his outward journey, if I recall. Returning, he bounced around the coast of Africa, went up the coast of Italy, back down to Africa, before finally returning to Ithaca from the west. Odysseus says his really big mistake was letting his crew kill and eat one of the sacred cattle of Helios, the sun, and all-white herd that neither calved nor died.

Robert Graves says the "white cattle" of the sun is a sort of riddle, the answer to which, is "clouds." If so, claiming to lasso and barbeque one of these is a tall-tale akin to Pecos Bill. But Odysseus was the sole survivor of his voyage and could play faster and looser with the facts than Theseus who had eye-witnesses and had to be a little more circumspect when it came to bending the truth.

Such were my thoughts on the way from Athens to Crete, touching down in front of the snowy peaks of Hania.

This was the sea Theseus crossed to kill the Minotaur, and returned - partway - with the Princess Ariadne who'd - predictably - fallen in love with him, agreeing to betray country and family. (The Minotaur was her half-brother by Queen Pasiphae and a sacred bull. It's complicated.)

Theseus stopped on an island, and Dionysius, falling in love with Ariadne, took her for his own. At least that's what Theseus claimed. Theseus was a big one for claiming things weren't his doing whenever they worked out to his advantage. He said the thing with the sails wasn't his doing either. Before sailing, he'd promised his father, King Aegeas, to raise white sails if he returned safely; otherwise the sails wouldbe black. When Aegeas saw the black sails on the horizon, he leapt to his death in despair, throwing himself into the sea that still bears his name, the Aegean.

Theseus said it was all a big misunderstanding, that he'd been asleep below decks and hadn't thought to tell the crew about the sails; what with killing the Minotaur, escaping Minos, and meeting Dionysisus, it had slipped his mind. These things happen. Of course, it did mean Theseus was now king, but you really can't hold him responsible. In a later episode of the same story, Daedelus and Icarus flew over this sea on their wax and feather wings. Only Daedelus made it. Flying from Crete to Sicily, they'd have been on a sharp diagonal course under my plane. "I just flew in from the coast, and, boy, are my arms tired!" is what Daedelus said when the King of Sicily welcomed him, only in those days it wasn't a joke, but just a statement of fact.

Jason sailed this patch of sea, too, although Odysseus only did so on his outward journey, if I recall. Returning, he bounced around the coast of Africa, went up the coast of Italy, back down to Africa, before finally returning to Ithaca from the west. Odysseus says his really big mistake was letting his crew kill and eat one of the sacred cattle of Helios, the sun, and all-white herd that neither calved nor died.

Robert Graves says the "white cattle" of the sun is a sort of riddle, the answer to which, is "clouds." If so, claiming to lasso and barbeque one of these is a tall-tale akin to Pecos Bill. But Odysseus was the sole survivor of his voyage and could play faster and looser with the facts than Theseus who had eye-witnesses and had to be a little more circumspect when it came to bending the truth.

Such were my thoughts on the way from Athens to Crete, touching down in front of the snowy peaks of Hania.

Published on April 16, 2011 06:06