Man Martin's Blog, page 225

May 15, 2011

Apophasis

Since I got off on the subject of litotes the other day, I thought I'd do a blog on my favorite figure of speech, apophasis. About.com defines it as "the mention of something in disclaiming intention of mentioning it--or pretending to deny what is really affirmed."

It's pretty rare to hear a good apophasis, which is why it's my favorite. Some examples include, "I'm not talking to you," "I'm not going to tell you what a butt-hole I think you are."

They're not neccessarilly rude, Marc Anthony gets off a beautiful apophasis when he tells the plebians, "It's good you know not you are Caesar's heirs." Even as a precocious five-year-old, I myself nearly made an apophasis at the dinner table when I naively asked, "Does Helen know about her birthday cake?" To which my mother sagely replied, "She does now."

Writing a blog about apophasis virtually requires you to cleverly use one to wrap up with, but the problem is they're so consarn hard to come up with. Wait a minute, I've got one! By golly, an apophasis and a paradox!

I don't have a clever ending for this blog.

It's pretty rare to hear a good apophasis, which is why it's my favorite. Some examples include, "I'm not talking to you," "I'm not going to tell you what a butt-hole I think you are."

They're not neccessarilly rude, Marc Anthony gets off a beautiful apophasis when he tells the plebians, "It's good you know not you are Caesar's heirs." Even as a precocious five-year-old, I myself nearly made an apophasis at the dinner table when I naively asked, "Does Helen know about her birthday cake?" To which my mother sagely replied, "She does now."

Writing a blog about apophasis virtually requires you to cleverly use one to wrap up with, but the problem is they're so consarn hard to come up with. Wait a minute, I've got one! By golly, an apophasis and a paradox!

I don't have a clever ending for this blog.

Published on May 15, 2011 03:44

May 14, 2011

Litotes and the Double Negative

Linguists tell us you can predict the direction the language is headed by how the Working Class speaks. (Working Class, what an invidious term, but there it is, and I'm not taking it back.) This means the rules of English in five hundred years are not being set by Harvard professors, but by Joe Six Pack. If so, then it's "Hello, Double Negative," and "Good-bye, Litotes."

"I don't have no money," still sounds wrong to my ears, but give us a half millenium and I'll get used to it. In most languages, negatives don't cancel each other out, they just add emphasis. English owes its unusual proscription against double negatives to 18th Century grammarians better versed in the strict rules of algebra than the fuzzy logic of grammar.

The sad thing is, as we wave good-bye to yet another slowly-departing rule of English, welcoming the double-negative means we will lose litotes.

Litotes is a figure of speech that asserts a positive by negating its opposite. "I don't have no money," actually means I have a little: not enough for the bald statement, "I have some money," but too much for, "I don't have any money." That's litotes, and it hits a very nuanced little target of meaning. But once Double Negatives have their way, it's farewell litotes forever. A sentence like, "I'm not without influence," would be completely opaque to an English speaker with no sense of negatives' canceling each other out, and "I'm not without influence," is a lovely sentence, a charming sentence.

But after all, how important are litotes anyway, given the enormous convenience and simplicity of being able to rip off with a good double- or even triple-negative? "She didn't never love him none." It does the soul good to see it there.

Besides, do I ever really use litotes? Does anyone?

Well, I don't never use them.

"I don't have no money," still sounds wrong to my ears, but give us a half millenium and I'll get used to it. In most languages, negatives don't cancel each other out, they just add emphasis. English owes its unusual proscription against double negatives to 18th Century grammarians better versed in the strict rules of algebra than the fuzzy logic of grammar.

The sad thing is, as we wave good-bye to yet another slowly-departing rule of English, welcoming the double-negative means we will lose litotes.

Litotes is a figure of speech that asserts a positive by negating its opposite. "I don't have no money," actually means I have a little: not enough for the bald statement, "I have some money," but too much for, "I don't have any money." That's litotes, and it hits a very nuanced little target of meaning. But once Double Negatives have their way, it's farewell litotes forever. A sentence like, "I'm not without influence," would be completely opaque to an English speaker with no sense of negatives' canceling each other out, and "I'm not without influence," is a lovely sentence, a charming sentence.

But after all, how important are litotes anyway, given the enormous convenience and simplicity of being able to rip off with a good double- or even triple-negative? "She didn't never love him none." It does the soul good to see it there.

Besides, do I ever really use litotes? Does anyone?

Well, I don't never use them.

Published on May 14, 2011 03:28

May 13, 2011

Zooming in Zooming Out

I once went to an exhibit of a minor Impressionist, some pal of Monet's or somebody, a fellow-painter who never quite made the grade. It only took seeing one canvas to understand why he was a minor Impressionist. It was a mountainscape of misty, snowy peaks, purples and ambers feathering into each other. I think a blustery sky came into it somewhere; I can't recall. What drew the attention was that in the foreground a pine-tree branch swept across the upper quadrant of the painting. It was as if we were standing behind that pine tree looking at the mountains in the distance.

I bet that painter thought as he was doing the branch, "Look at me go! Now I'm going to cut loose and show 'em what I can really do!" It really was a sort of marvel. You could count the needles, and the crusty pinebark was so lovingly rendered, it could have been used in a botany lecture.

The painting sucked.

I didn't want to admire his pine branch. I wanted to see mountains.

As writers, we're told detail, detail, detail! (In the North they say, deTAIL, but in the civilized world, we say, DEEtail.) We're told that the more detailed our descriptions, the better our writing will be. But is this true? The devil is in the details, the saying goes, but sometimes the devil IS the detail. We can get so carried away with the damn pinebranch in our line of sight, we forget the mountains in the distance.

Wordsworth, no slouch as a writer, doesn't bother with detail, but gives an entire city in three brushstrokes in "Westminster Bridge:"

Earth has not anything to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne'er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that. mighty heart is lying still!

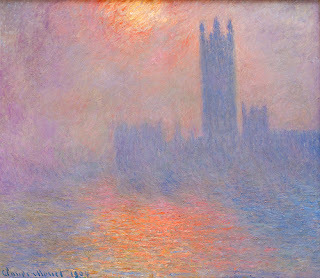

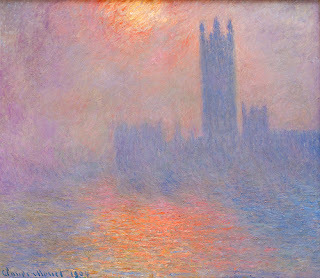

(So you won't think I'm a smartypants, Cleanth Brooks pointed out the strirring lack of detail of this poem before I ever noticed it.) I know there are ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples - but it's a vague jumble. I have a sense that his gaze is traveling from the water to the land. I know there are houses and a river, but there are no details. In spite of being smokeless, the view is hazy for me. But what a wonderful poem; it fills you with that same shock of awe-struck calm (how could those emotions coincide?) that Wordsworth felt. It is the same sense we get in the Monet painting - a vague and shimmering beauty that is deeply felt but owes itself to the lack of detail.

(So you won't think I'm a smartypants, Cleanth Brooks pointed out the strirring lack of detail of this poem before I ever noticed it.) I know there are ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples - but it's a vague jumble. I have a sense that his gaze is traveling from the water to the land. I know there are houses and a river, but there are no details. In spite of being smokeless, the view is hazy for me. But what a wonderful poem; it fills you with that same shock of awe-struck calm (how could those emotions coincide?) that Wordsworth felt. It is the same sense we get in the Monet painting - a vague and shimmering beauty that is deeply felt but owes itself to the lack of detail.

So when should a writer use a soft focus, and when not? When should he put gauze over the lens?

Frost has lines that zoom in beautifully in "Birches,"

...life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig's having lashed across it open.

Now there's a time for your close-up of a tree branch. Of course you're going to see that twig, it lashed across your open eye, for God's sake! And the tickling cobwebs. There's some vivid detail for you. It works, of course, because if you've ever had that experience, you know that's all you can think about. The entire woods for you, the whole world, is those cobwebs and your weeping eye.

It's not enough to number the spikey pine needles, and give a shadow to each scab of bark. Most of the time you'll have to leave that stuff out unless it's something that must intrude on the character's consciousness. Otherwise, keep to the soft focus, perhaps, of daily awareness. That way you'll still see the forest for the trees.

I bet that painter thought as he was doing the branch, "Look at me go! Now I'm going to cut loose and show 'em what I can really do!" It really was a sort of marvel. You could count the needles, and the crusty pinebark was so lovingly rendered, it could have been used in a botany lecture.

The painting sucked.

I didn't want to admire his pine branch. I wanted to see mountains.

As writers, we're told detail, detail, detail! (In the North they say, deTAIL, but in the civilized world, we say, DEEtail.) We're told that the more detailed our descriptions, the better our writing will be. But is this true? The devil is in the details, the saying goes, but sometimes the devil IS the detail. We can get so carried away with the damn pinebranch in our line of sight, we forget the mountains in the distance.

Wordsworth, no slouch as a writer, doesn't bother with detail, but gives an entire city in three brushstrokes in "Westminster Bridge:"

Earth has not anything to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne'er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that. mighty heart is lying still!

(So you won't think I'm a smartypants, Cleanth Brooks pointed out the strirring lack of detail of this poem before I ever noticed it.) I know there are ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples - but it's a vague jumble. I have a sense that his gaze is traveling from the water to the land. I know there are houses and a river, but there are no details. In spite of being smokeless, the view is hazy for me. But what a wonderful poem; it fills you with that same shock of awe-struck calm (how could those emotions coincide?) that Wordsworth felt. It is the same sense we get in the Monet painting - a vague and shimmering beauty that is deeply felt but owes itself to the lack of detail.

(So you won't think I'm a smartypants, Cleanth Brooks pointed out the strirring lack of detail of this poem before I ever noticed it.) I know there are ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples - but it's a vague jumble. I have a sense that his gaze is traveling from the water to the land. I know there are houses and a river, but there are no details. In spite of being smokeless, the view is hazy for me. But what a wonderful poem; it fills you with that same shock of awe-struck calm (how could those emotions coincide?) that Wordsworth felt. It is the same sense we get in the Monet painting - a vague and shimmering beauty that is deeply felt but owes itself to the lack of detail.So when should a writer use a soft focus, and when not? When should he put gauze over the lens?

Frost has lines that zoom in beautifully in "Birches,"

...life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig's having lashed across it open.

Now there's a time for your close-up of a tree branch. Of course you're going to see that twig, it lashed across your open eye, for God's sake! And the tickling cobwebs. There's some vivid detail for you. It works, of course, because if you've ever had that experience, you know that's all you can think about. The entire woods for you, the whole world, is those cobwebs and your weeping eye.

It's not enough to number the spikey pine needles, and give a shadow to each scab of bark. Most of the time you'll have to leave that stuff out unless it's something that must intrude on the character's consciousness. Otherwise, keep to the soft focus, perhaps, of daily awareness. That way you'll still see the forest for the trees.

Published on May 13, 2011 09:37

May 12, 2011

Signified and Signifier

We owe these terms to the Swiss linguist Saussure who said that the relationship between a word and its meaning was purely arbitrary, the result of historical chance. (By the way, "historical chance," is that a redundancy or an oxymoron?) The word "dog" seems especially doggy to English-speakers, but that's only due to long association of the word and the animal. After all, to a Frenchman, "chien" seems just as evocative of dogginess, as "perro" is to a Spaniard, or "hund" to a German.

But Saussure is wrong, or at least partly wrong. The way I know he is wrong is that there are some English words that aren't as satisfactory as their foreign counterparts. The word "water" for example, just doesn't do. My friend John Blair pronounces it with a liquid sound in the middle so it's almost like "walter." He's careful to enunciate the hard "t" and the "r." When he says "water," it sounds like water. You can imagine it spilling over a smooth boulder into a pool beneath. But the rest of us say something more like "wadda." Bottled water comes out like "boddle dwadda." Good Lord, no wonder I never drink that stuff. It doesn't even sound liquid. "Boddle dwadda" is a name you'd give an arrangement of semi-round stones. The Spanish "agua" is much better; it at least feels like a good mouthful of water, although it does tend to cloy at the back of the throat.

And "snake." There's very little snakelike about the word. It's long and skinny, I'll grant you, but there are no curves in it. It stretches out in a straight line. It is a wooden snake, and a badly-carved one at that. Now the Spanish "culabra," there's a snake for you! It's all muscles and coils.

And as for the dog example at the start of the essay, yes, I will affirm, there is something uniquely doglike about the word "dog." You can tell it has a belly and heavy paws. The word has weight. In the South, where our dogs are especially well-fed and content, the word sags in the middle and takes long naps, "dawg." And "perro" is a perfectly suitable word for a dog as well. You can feel the pressure of that moist nose in the "p" and who wouldn't recognize the growling double-r in the center. "Chien" is clearly a different kind of dog, although oddly enough, not a French poodle. Chien is a little black dog with a spikey tail. I believe he may be forced to wear a little dog sweater in the wintertime. And "hund." What can you say? A hund is big and regal. When it is calm and alert, it lies in front of the fireplace, with its head raised, and paws folded beneath its chest like a lion. No one would dream of calling a "hund" - a Great Dane, for instance- a "chien."

Well, a Frenchman might. But in his heart, he would know it was wrong.

But Saussure is wrong, or at least partly wrong. The way I know he is wrong is that there are some English words that aren't as satisfactory as their foreign counterparts. The word "water" for example, just doesn't do. My friend John Blair pronounces it with a liquid sound in the middle so it's almost like "walter." He's careful to enunciate the hard "t" and the "r." When he says "water," it sounds like water. You can imagine it spilling over a smooth boulder into a pool beneath. But the rest of us say something more like "wadda." Bottled water comes out like "boddle dwadda." Good Lord, no wonder I never drink that stuff. It doesn't even sound liquid. "Boddle dwadda" is a name you'd give an arrangement of semi-round stones. The Spanish "agua" is much better; it at least feels like a good mouthful of water, although it does tend to cloy at the back of the throat.

And "snake." There's very little snakelike about the word. It's long and skinny, I'll grant you, but there are no curves in it. It stretches out in a straight line. It is a wooden snake, and a badly-carved one at that. Now the Spanish "culabra," there's a snake for you! It's all muscles and coils.

And as for the dog example at the start of the essay, yes, I will affirm, there is something uniquely doglike about the word "dog." You can tell it has a belly and heavy paws. The word has weight. In the South, where our dogs are especially well-fed and content, the word sags in the middle and takes long naps, "dawg." And "perro" is a perfectly suitable word for a dog as well. You can feel the pressure of that moist nose in the "p" and who wouldn't recognize the growling double-r in the center. "Chien" is clearly a different kind of dog, although oddly enough, not a French poodle. Chien is a little black dog with a spikey tail. I believe he may be forced to wear a little dog sweater in the wintertime. And "hund." What can you say? A hund is big and regal. When it is calm and alert, it lies in front of the fireplace, with its head raised, and paws folded beneath its chest like a lion. No one would dream of calling a "hund" - a Great Dane, for instance- a "chien."

Well, a Frenchman might. But in his heart, he would know it was wrong.

Published on May 12, 2011 03:23

May 11, 2011

Great Movies

Over the last two nights my wife and I rewatched The Godfather. What an amazing film that is. It's one of the few movies Nancy and I own. What struck me most this time was Copala's use of color. Somewhere an art teacher or museum docent told me that colors are more saturated in semidarkness. While I knew that bright lights can wash a color out, the claim still seemed unlikely to me. Watching The Godfather, though, I know it's true. The darkness only makes the reds and violets deeper and more sumptuous. And it is one dark film. I swear, it's the only film I've ever seen where someone opens a door and the room gets darker.

This set me to thinking about the best films I've ever seen. This is hard, because there are a lot of very good movies out there, and even some that are stand-out great. But what are the movies at the very head of the list? The ones that shook you by your shoulders until your teeth rattled? Casablanca is a great movie, as is Citizen Kane, but neither of them thrill or chill me. Nancy's list includes Erin Brockovich and Amelie. Here's mine, in no particular order; some if I saw again I might not be so impressed with (this happened with War of the Worlds which I saw first as a child and later as an adult) but at the time, seeing these I thought, "Wow, now THAT was a movie." Parenthetically, I might say the first movie to strike me this way was The Ghost and Mr Chicken, but that was only because it was the first movie I saw in a theater.

The Wizard of Oz - an early favorite that turns out to have legs. I not only love the sometimes jaw-dropping cinematography, but the writing and the performances.

The Color Purple

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Star Wars - I'm sure if I saw it again, I'd roll my eyes, but at the time, I'd simply never seen anything like it before. It was such a movie.

The Godfather I and II

Is that it? Is that all I can think of? Strangely, some of my favorite directors don't make the list. Rear Window is a superlative movie, but it just doesn't measure up to The Color Purple. Who couldn't love Fargo, but it's no Star Wars. Crimes and Misdemeanors. A great, great film. But not Godfather great.

So them's my picks, what's yours?

This set me to thinking about the best films I've ever seen. This is hard, because there are a lot of very good movies out there, and even some that are stand-out great. But what are the movies at the very head of the list? The ones that shook you by your shoulders until your teeth rattled? Casablanca is a great movie, as is Citizen Kane, but neither of them thrill or chill me. Nancy's list includes Erin Brockovich and Amelie. Here's mine, in no particular order; some if I saw again I might not be so impressed with (this happened with War of the Worlds which I saw first as a child and later as an adult) but at the time, seeing these I thought, "Wow, now THAT was a movie." Parenthetically, I might say the first movie to strike me this way was The Ghost and Mr Chicken, but that was only because it was the first movie I saw in a theater.

The Wizard of Oz - an early favorite that turns out to have legs. I not only love the sometimes jaw-dropping cinematography, but the writing and the performances.

The Color Purple

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Star Wars - I'm sure if I saw it again, I'd roll my eyes, but at the time, I'd simply never seen anything like it before. It was such a movie.

The Godfather I and II

Is that it? Is that all I can think of? Strangely, some of my favorite directors don't make the list. Rear Window is a superlative movie, but it just doesn't measure up to The Color Purple. Who couldn't love Fargo, but it's no Star Wars. Crimes and Misdemeanors. A great, great film. But not Godfather great.

So them's my picks, what's yours?

Published on May 11, 2011 03:14

May 10, 2011

Le Fond

My wife gets after me from time to time to tidy up my desk. Books I've partly read, am re-reading, or intend to read lie amid loose papers with notes, doodles, and idle jottings. Also notebooks with annotated manuscripts waiting to be tossed into the trash. Not to mention occaisional newspaper stories and magazine articles that caught my eye for Lord knows what reason.

It's a mess, alright, but in the throes of the creative process I find myself thinking, there was a passage in that book by what's-her-name that had a very similar scene - and I'm off looking for another book to add to the pile - or an idea will hit me, and I think, "I can't use this in this scene, but maybe later on..." And I scribble myself a note to remember. More junk.

Really, Nancy is a lot more patient with me than I deserve.

I get up early and write before going to work. When I get home, I sit my lazy butt in a chair and type or send emails while she makes dinner. This is not quite as male-chauvinist-piggy as it sounds. I can put a meal on the table, Nancy happens to be a really incredible cook. She can do things just by sauteeing chicken parts that would make you weep, they're so good. And her breaded porkchops! I chop onions and bring things up from the freezer, but cooking while Nancy's in the house is like offering Mario Andretti a ride to work.

I do clean up afterwards. I do that much.

A couple of times, though, I've gotten in dutch even doing that. I'll see a skillet with drippings and little scabs of meat and flour in it, and helpfully wash it out in the sink. This is something I shouldn't do. "It's le fond!" Nancy says angrilly. "Le fond! Le fond!" Evidently, in high-tone cooking such as Nancy does, this residue is a highly-prized ingredient to be combined with other ingredients later for that touch of supreme deliciousness.

So now I pretty much stay out of the kitchen until after dinner. Then I clean up. And not very well. Like I say, in the evenings, I'm pretty tired.

Pretty soon I'm going to have to summon the energy to tackle my desk. Start cleaning up and putting away. There's only so much Nancy will put up with, after all.

But all those jottings, scribbles, dog-eared books, and pored-over pages, aren't just clutter. They're the bits and scraps of other ideas. The scrapings and residues that I will combine to make a scene or character.

How can I explain that to Nancy.

It's le fond! Le fond!

It's a mess, alright, but in the throes of the creative process I find myself thinking, there was a passage in that book by what's-her-name that had a very similar scene - and I'm off looking for another book to add to the pile - or an idea will hit me, and I think, "I can't use this in this scene, but maybe later on..." And I scribble myself a note to remember. More junk.

Really, Nancy is a lot more patient with me than I deserve.

I get up early and write before going to work. When I get home, I sit my lazy butt in a chair and type or send emails while she makes dinner. This is not quite as male-chauvinist-piggy as it sounds. I can put a meal on the table, Nancy happens to be a really incredible cook. She can do things just by sauteeing chicken parts that would make you weep, they're so good. And her breaded porkchops! I chop onions and bring things up from the freezer, but cooking while Nancy's in the house is like offering Mario Andretti a ride to work.

I do clean up afterwards. I do that much.

A couple of times, though, I've gotten in dutch even doing that. I'll see a skillet with drippings and little scabs of meat and flour in it, and helpfully wash it out in the sink. This is something I shouldn't do. "It's le fond!" Nancy says angrilly. "Le fond! Le fond!" Evidently, in high-tone cooking such as Nancy does, this residue is a highly-prized ingredient to be combined with other ingredients later for that touch of supreme deliciousness.

So now I pretty much stay out of the kitchen until after dinner. Then I clean up. And not very well. Like I say, in the evenings, I'm pretty tired.

Pretty soon I'm going to have to summon the energy to tackle my desk. Start cleaning up and putting away. There's only so much Nancy will put up with, after all.

But all those jottings, scribbles, dog-eared books, and pored-over pages, aren't just clutter. They're the bits and scraps of other ideas. The scrapings and residues that I will combine to make a scene or character.

How can I explain that to Nancy.

It's le fond! Le fond!

Published on May 10, 2011 03:26

May 9, 2011

What if you win the lottery (what if you don't)

"Can I be a writer?" people ask me in various ways. The answer is, "Of course, you don't need my permission to do that."

What they really mean to ask is, "Can I make money with this? Can I make a living at it?"

The answer to that one is, sadly, no.

Terry Kay once told me he estimated fifty people in the US make their living writing fiction. I don't think the number is that high.

What saddens me about people who "want to be a writer" so they can make big bucks and escape the rat race, isn't just the enormous odds stacked against them, it's that their lifeplan isn't to write; it's to write "ONE BIG THING" and spend the rest of their lives being rich and famous.

Are you someone who wants to be a writer? Really? Then ask yourself this question: If I won the lottery tomorrow and had more money than I could ever spend, would I still write? If the answer is yes, you're a writer. If no, you're a wannabe. Sometimes wannabes make it; it's a screwy world, after all, but in the writing biz, success goes to those who perservere. And perservere .

And what if you never win the lottery? What if your life continues more or less as it is right now? Would you still write? If the answer is yes, you're a writer. After all, you have to be. You're writing.

What they really mean to ask is, "Can I make money with this? Can I make a living at it?"

The answer to that one is, sadly, no.

Terry Kay once told me he estimated fifty people in the US make their living writing fiction. I don't think the number is that high.

What saddens me about people who "want to be a writer" so they can make big bucks and escape the rat race, isn't just the enormous odds stacked against them, it's that their lifeplan isn't to write; it's to write "ONE BIG THING" and spend the rest of their lives being rich and famous.

Are you someone who wants to be a writer? Really? Then ask yourself this question: If I won the lottery tomorrow and had more money than I could ever spend, would I still write? If the answer is yes, you're a writer. If no, you're a wannabe. Sometimes wannabes make it; it's a screwy world, after all, but in the writing biz, success goes to those who perservere. And perservere .

And what if you never win the lottery? What if your life continues more or less as it is right now? Would you still write? If the answer is yes, you're a writer. After all, you have to be. You're writing.

Published on May 09, 2011 02:45

May 8, 2011

Mother's Day

In John Blair's History of the English Drama Class at Georgia College in Milledgeville, Georgia, I had a seat next to the most beautiful girl I'd ever seen.

God, she was something. My neck got sore looking to the front of the class because I didn't want her to catch me staring at her. As often as I could manage, though, I let my gaze wander to see if she was really as stunning as I thought. Damn. She was.

She didn't speak to me, nor I to her. I was too shy and she was out of my league by several light years. I wasn't even sure of her name. Sarah or Carol or something.

Then one day, my buddy Charles "Drip" Waldrip asked me to assist with a class presentation . It was on the play "Tis Pity She's a Whore" (This is an actual title) and he wanted me to pretend to interrupt the first part of his talk. At the time Johnny Carson and Ed McMahon had a routine when Ed would say something like, "This news article tells you everything you need to know about dogs." And then Johnny would say, "Not true, Alpo breath," and go off on some silly riff about raising pooches.

I was to interrupt Drip, saying how complete the handout was and how there was nothing more to add, then Drip was going say, "Not so fast, Petrarchan breath," and begin his talk.

So the day of class, Drip gives out the handouts, and I begin my spiel, saying how great the handout was, how complete, and was just about to say there was nothing else to add, when WHAM! The prettiest girl I'd ever seen yells "Shut up!" and whaps the side of my head with the Riverside Shakespeare, hardbound and ten inches thick. Stunned silence ensued. If Drip wanted a surprise beginning to his talk, he'd succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

All was made clear, and the girl - whose name turned out to be Nancy - and I begin dating shortly thereafter. This July marks thirty years of marriage.

I count that day in John Blair's History of English Drama as one of the most fortunate of my life. We still have the Riverside Shakespeare, and though it doesn't actually bear the dented impression of my skull, I tell people it does.

Never let a day pass, Man Martin, without remembering how lucky you are. I love you, darling.

Happy Mother's Day.

God, she was something. My neck got sore looking to the front of the class because I didn't want her to catch me staring at her. As often as I could manage, though, I let my gaze wander to see if she was really as stunning as I thought. Damn. She was.

She didn't speak to me, nor I to her. I was too shy and she was out of my league by several light years. I wasn't even sure of her name. Sarah or Carol or something.

Then one day, my buddy Charles "Drip" Waldrip asked me to assist with a class presentation . It was on the play "Tis Pity She's a Whore" (This is an actual title) and he wanted me to pretend to interrupt the first part of his talk. At the time Johnny Carson and Ed McMahon had a routine when Ed would say something like, "This news article tells you everything you need to know about dogs." And then Johnny would say, "Not true, Alpo breath," and go off on some silly riff about raising pooches.

I was to interrupt Drip, saying how complete the handout was and how there was nothing more to add, then Drip was going say, "Not so fast, Petrarchan breath," and begin his talk.

So the day of class, Drip gives out the handouts, and I begin my spiel, saying how great the handout was, how complete, and was just about to say there was nothing else to add, when WHAM! The prettiest girl I'd ever seen yells "Shut up!" and whaps the side of my head with the Riverside Shakespeare, hardbound and ten inches thick. Stunned silence ensued. If Drip wanted a surprise beginning to his talk, he'd succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

All was made clear, and the girl - whose name turned out to be Nancy - and I begin dating shortly thereafter. This July marks thirty years of marriage.

I count that day in John Blair's History of English Drama as one of the most fortunate of my life. We still have the Riverside Shakespeare, and though it doesn't actually bear the dented impression of my skull, I tell people it does.

Never let a day pass, Man Martin, without remembering how lucky you are. I love you, darling.

Happy Mother's Day.

Published on May 08, 2011 05:17

May 7, 2011

How Can I Get Published?

This is the big question, one I get asked on a frequent basis by new writers.

The saddest and quickest and most honest answer, which I never give, is "do better work." That's the foundation of all other advice. The easy answer is simply submit your work. If it's short, go to Newpages.com and you can browze zillions of journals, magazines, and online publications that are looking for material. If it's a novel, check the Writers Market for reputable literary agents to represent you. If you want to be a cowboy about it - and who doesn't like to be a cowboy? - you can even submit it to publishers directly. There are a few - but a rapidly dwindling number - of publishers that still look at unagented submissions. I have one other trick, taught me by Valerie Storey, called "the rule of twelve." It says that if you send out twelve submissions at the same time, one of them will come back with a positive response. Not an acceptance, necessarilly, just a positive response: even an encouraging hand-written rejection can be a big boost to a fledgling writer. Of course the rule of twelve also means you have to disregard policies against "no simultaneous submissions," but Iwon't tell if you won't.

But all of that comes later. How much later depends on your own fortitude.

If you're writing only so that you can get published, you're going to be quickly discouraged and give it up. If you're writing so you can get rich, you're just flat delusional. (I know, I know, J K Rowling did it. But just because she got rich doesn't mean she wasn't crazy. If you think you're Napoleon, you're still a lunatic even if you end up conquering Europe.)

First focus on doing the best work you possibly can. Then go back and make it better.

Robert Frost called this "building soil," a great metaphor we amateur gardeners fully understand. We bury compost and turn under leaf mulch, enriching, and enriching, and enriching the soil all year before we put in the first seed. For an avid gardener, good rich soil, as black as a beetle's back, is as delightful as that first ripe tomato.

Here's Frost's advice about what to do with writing before "rushing it to market."

"The thought I have, and my first impulse is

To take to market- I will turn it under.

The thought from that thought- I will turn it under.

And so on to the limit of my nature."

The limit of his nature, in other words, he will craft and ponder, craft and ponder, to his very utmost. What is the goal of this? How rich should the soil be?

"Turn the farm in upon itself

Until it can contain itself no more

But sweating full, drips wine and oil a little."

"How can I get published?" is the wrong question. The right question is "How do I write work worthy of publication?" There's your recipe. Don't dash headlong into publication; work the soil, work it to the limit of your nature. Not just until you sweat, but until the pages sweat. Sweat oil and wine.

The saddest and quickest and most honest answer, which I never give, is "do better work." That's the foundation of all other advice. The easy answer is simply submit your work. If it's short, go to Newpages.com and you can browze zillions of journals, magazines, and online publications that are looking for material. If it's a novel, check the Writers Market for reputable literary agents to represent you. If you want to be a cowboy about it - and who doesn't like to be a cowboy? - you can even submit it to publishers directly. There are a few - but a rapidly dwindling number - of publishers that still look at unagented submissions. I have one other trick, taught me by Valerie Storey, called "the rule of twelve." It says that if you send out twelve submissions at the same time, one of them will come back with a positive response. Not an acceptance, necessarilly, just a positive response: even an encouraging hand-written rejection can be a big boost to a fledgling writer. Of course the rule of twelve also means you have to disregard policies against "no simultaneous submissions," but Iwon't tell if you won't.

But all of that comes later. How much later depends on your own fortitude.

If you're writing only so that you can get published, you're going to be quickly discouraged and give it up. If you're writing so you can get rich, you're just flat delusional. (I know, I know, J K Rowling did it. But just because she got rich doesn't mean she wasn't crazy. If you think you're Napoleon, you're still a lunatic even if you end up conquering Europe.)

First focus on doing the best work you possibly can. Then go back and make it better.

Robert Frost called this "building soil," a great metaphor we amateur gardeners fully understand. We bury compost and turn under leaf mulch, enriching, and enriching, and enriching the soil all year before we put in the first seed. For an avid gardener, good rich soil, as black as a beetle's back, is as delightful as that first ripe tomato.

Here's Frost's advice about what to do with writing before "rushing it to market."

"The thought I have, and my first impulse is

To take to market- I will turn it under.

The thought from that thought- I will turn it under.

And so on to the limit of my nature."

The limit of his nature, in other words, he will craft and ponder, craft and ponder, to his very utmost. What is the goal of this? How rich should the soil be?

"Turn the farm in upon itself

Until it can contain itself no more

But sweating full, drips wine and oil a little."

"How can I get published?" is the wrong question. The right question is "How do I write work worthy of publication?" There's your recipe. Don't dash headlong into publication; work the soil, work it to the limit of your nature. Not just until you sweat, but until the pages sweat. Sweat oil and wine.

Published on May 07, 2011 05:00

May 6, 2011

Book:Movie

While visiting Greece I finished Charles Portis' True Grit.

It is as similar to the movie version - both movie versions - as any novel I have ever read. I can only imagine that the Coen brothers and Henry Hathaway before them must have taken the novel and filmed it page by page. So having seen two extraordinary films, both very similar, what did I gain by reading the book? Is there anything more to it than just another "version," as if someone filmed True Grit yet a third time, with John Travolta as Rooster Cogburn and Adam Sandler in drag as Mattie?

The reason the novel will always be different - if not always superior - to the movie is because the novel gives greater intimacy with the characters.

Alfred Hitchcock said that whereas the stage is objective, film is subjective. What he meant is that film can suggest the interior experience of a character in a way that a stage play cannot. If two characters kiss on stage, we witness it, and that's that. In a Hitchcock film, we see a close up of Jimmy Stewart's face. Then we see a shot of Grace Kelly, from Stewart's point of view, coming in for the kiss. Then we see her brush her lips against his. Then we see Kelly's face again. And last Stewart's reaction. The sequence of shots give us the illusion that we're right there with Jimmy Stewart getting smooched.

But even a master like Hitchcock can't tell you what goes through Stewart's mind. When you write, you can't help but tell how to think about it: even choosing a synonymn for "kiss:" brush lips, smooch, kiss - is going to inform the reader how to feel about this transaction.

The stage is objective. Film is subjective. The written word is subjective to the second power.

It is as similar to the movie version - both movie versions - as any novel I have ever read. I can only imagine that the Coen brothers and Henry Hathaway before them must have taken the novel and filmed it page by page. So having seen two extraordinary films, both very similar, what did I gain by reading the book? Is there anything more to it than just another "version," as if someone filmed True Grit yet a third time, with John Travolta as Rooster Cogburn and Adam Sandler in drag as Mattie?

The reason the novel will always be different - if not always superior - to the movie is because the novel gives greater intimacy with the characters.

Alfred Hitchcock said that whereas the stage is objective, film is subjective. What he meant is that film can suggest the interior experience of a character in a way that a stage play cannot. If two characters kiss on stage, we witness it, and that's that. In a Hitchcock film, we see a close up of Jimmy Stewart's face. Then we see a shot of Grace Kelly, from Stewart's point of view, coming in for the kiss. Then we see her brush her lips against his. Then we see Kelly's face again. And last Stewart's reaction. The sequence of shots give us the illusion that we're right there with Jimmy Stewart getting smooched.

But even a master like Hitchcock can't tell you what goes through Stewart's mind. When you write, you can't help but tell how to think about it: even choosing a synonymn for "kiss:" brush lips, smooch, kiss - is going to inform the reader how to feel about this transaction.

The stage is objective. Film is subjective. The written word is subjective to the second power.

Published on May 06, 2011 03:14