Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 4

April 23, 2018

Revisiting Night Streets, Part 2

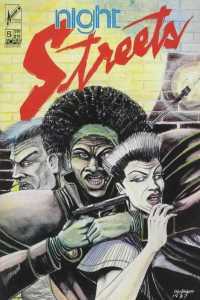

Previously in Part 1, I wrote about the eighties comic Night Streets, which ended at issue #5, promising a storyline conclusion in issue #6, which never appeared.

The unresolved cliffhanger is a special kind of torture. If you’ve ever gotten emotionally invested in a story—whether a movie, TV, comic, or novel—the idea that there will never be a resolution can drive you bonkers. Examples include Melanie Rawn’s Exiles trilogy, Carnivale, and the original Twin Peaks. I’ve even got one of my own: my Memphis Vampires novels (Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood) were supposed to be a trilogy, but sales didn’t merit the third one (which would have been called Blood Will Rise Again).

But I’ve discovered a new form of cliffhanging torture: the one where there was a long-ago finale, but I didn’t know about it.

In my last post, I wrote about the comic Night Streets, a black-and-white series that ran for five issues in the late 80s. Issue #5 promised a conclusion to the first storyline in the next issue, but it never appeared, and the company went out of business. So for thirty years—thirty years—I thought of this as an unresolved, eternally unfinished story.

In my last post, I wrote about the comic Night Streets, a black-and-white series that ran for five issues in the late 80s. Issue #5 promised a conclusion to the first storyline in the next issue, but it never appeared, and the company went out of business. So for thirty years—thirty years—I thought of this as an unresolved, eternally unfinished story.

And then, last month, I discovered that there was, in fact, a conclusion. The prior issues, and the material intended for issues #6 and 7, were included in two graphic novel compilations released in 1990.

To say I was gobsmacked is a grand understatement. As I mentioned in the previous post, over the years I’d poked around online to see what articles and reviews might be out there, and had found very little; certainly I’d never run across a single mention of these collections. I immediately went to eBay and found them.

Not only was it a return to a story I’d never expected to revisit, since it was created at the same time as the prior issues (as opposed to being newly created), it was a return to the feel, and a vivid reminder of why I loved it so much. Reading the truly final pages of Night Streets after all this time really took me back, and conjured an emotion I’d never experienced before: a very specific mix of excitement, anticipation, nostalgia, and a sense of completion.

And then I learned there was still more.

There was a two-part Night Streets story done for the Arrow Anthology comic. Written a decade after the series’ abortive run, it was set in the year 2024 and concerned vigilante Black Dahlia’s daughter, Blossom, telling her own granddaughter about events that happened in the 90s.

There was a two-part Night Streets story done for the Arrow Anthology comic. Written a decade after the series’ abortive run, it was set in the year 2024 and concerned vigilante Black Dahlia’s daughter, Blossom, telling her own granddaughter about events that happened in the 90s.

I quickly tracked down those issues. The story, “Crimson and Clover,” functions as a marvelous coda. In the bracketing sections, we learn that at some point Blossom has written a book called My Mother Was the Black Dahlia, which means Shantel’s secret identity is now public knowledge. Prompted by her granddaughter’s upcoming return to school, Blossom relates the main story, which began at the end of her (Blossom’s) senior year.

There are so many great things about this little tale. Chief among them is seeing that the Black Dahlia still works as a vigilante in the 90s; the list of middle-aged female superheroes is pretty damn short. She has a partner, Blonde Venus, and the case is one that strikes close to home. And it involves no supervillain, or even Felonious Katt; it’s a gritty little noir story about bad choices.

So now it seemed there was only one more thing I needed to complete this little quest: a conversation with Night Streets’ creator, writer, and artist, Mark Bloodworth himself.

Which is coming soon.

End of Part 2.

Read Part 1 here.

If you remember Night Streets, let me know in the comments.

April 16, 2018

Revisiting Night Streets, Part 1

With every bit of information and history seemingly at our fingertips, it can be hard to recall that once, finding out things was much harder. Occasionally, though, you run across a topic that hasn’t been done to death on the web, and for which there’s virtually no information. Then you have to roll up your sleeves and start digging. So to give you some background, let me tell you a little story…

In the 80s and early 90s, I bought comics regularly. I had pull lists at multiple stores, preferring mostly the independent black and white titles that exploded on the scene in the wake of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Over the years I’ve sold or given away a lot of them, but I’ve held on to the ones that still speak to me: Alan Moore’s Miracleman and Watchmen, the all-watercolor adaptation of The Vampire Lestat, Martin Powell and Seppo Makinen’s Scarlet by Gaslight, and so forth. But all those are fairly well-known, and have either been reissued or kept in print.

Then there’s Mark Bloodworth’s Night Streets, from Michigan’s Arrow Comics, which ran for five issues from 1987-1989.

Night Streets, as its noir-ish title implies, follows crime in an unnamed city, encompassing the gangs, the police, the crusading reporters (remember those?), and even the female vigilante Black Dahlia. Oh, and the head of one criminal organization is a seven-foot-tall bipedal talking cat. And he is most definitely not a joke.

Night Streets, as its noir-ish title implies, follows crime in an unnamed city, encompassing the gangs, the police, the crusading reporters (remember those?), and even the female vigilante Black Dahlia. Oh, and the head of one criminal organization is a seven-foot-tall bipedal talking cat. And he is most definitely not a joke.

There’s no explanation for Felonious Katt in the five extant issues; he simply is. He was created by Rob Knight and Ralph Griffith for an unrelated series in Arrow’s Fantastic Fanzine, and turned over to Bloodworth for his new book. Katt becomes one of the moral centers for the story, along with the Black Dahlia.

The Dahlia prowls the city at night, while during the day she’s a single mom with an office job. Her best friend Mal helps with her investigations, as well as writing and drawing a comic book about her exploits. She’s considered an ally by most of the cops, and spends as much time ferreting out information as she does breaking heads.

If I had to choose a single word to describe the series, it would be dense. And not in an overly-complex, confusing way, but more novelistic. Artist Bloodworth illustrates writer Bloodworth’s stories in crowded, heavily-detailed black and white panels that really capture that late-80s urban sense: punk fashions, extreme hair, nightclubs, and casual smoking. The plethora of characters could be overwhelming, but the writing and art are sharp enough that they never are.

I don’t consider myself any sort of obsessive comics expert here; others may know far more about antecedents and precedents. Certainly other comics I read around the same time had realistic settings and characters with no superpowers—the Hernandez Brothers began Love and Rockets in 1982, and it was true slice of life stuff. And of course the list of night-prowling vigilantes goes way, way back. Even the idea of an anthropomorphized animal in a realistic setting was nothing unusual, especially in independent comics; Robert Crumb began Fritz the Cat in the early sixties, and Art Spielgelman’s Maus was in the near future.

But there was something about the way Bloodworth pulled these elements together that created something new, or at least nothing I’d encountered before. This was a world that felt tangible enough to step into, as if the nameless city existed out their somewhere and could be visited. This was no Metropolis or Gotham, places where colorful costumes fit right in; this was something darker, and meaner, and for lack of a better word, pettier. Everyone’s actions came from a place of self-interest, as they usually do in the real world, and that made the moments of selflessness and altruism stand out in stark relief.

The first (and only) story arc, “Mob Rules,” covered six issues. And yes, you read correctly above: only five came out. At the end of the fifth, it promises the conclusion in the next issue, which never appeared. Titles came and went quickly in those days, often with extensive gaps between issues, and without the internet there were few sources for behind-the-scenes gossip or explanations.

So for me, Night Streets remained a great unfinished story that never got the attention it deserved (although Harlan Ellison did send a fan letter). I usually get blank looks when I mention it, even when I add, “you know, the one where the crime lord’s a giant talking cat.” The five issues are still available, at reasonable prices for a thirty-year-old independent comic. Occasionally I poke around online to see if anyone else is talking about it, but with very little results.

Until now.

Because I just found out…well, you’ll see.

End of Part 1.

If you remember Night Streets, let me know in the comments.

April 2, 2018

Serendipity, Saragossa, and Moonshine

When first pondering the story that would become The Fairies of Sadieville, my initial idea was one of form. I’d just read Jan Patocki’s The Manuscript Found in Saragossa and seen the Polish film adaptation, The Saragossa Manuscript. Both novel and film are “nesting” or “frame” stories, in which a tale is told within another tale, which is told within another tale, sometimes for multiple levels, like Russian nesting dolls.

When first pondering the story that would become The Fairies of Sadieville, my initial idea was one of form. I’d just read Jan Patocki’s The Manuscript Found in Saragossa and seen the Polish film adaptation, The Saragossa Manuscript. Both novel and film are “nesting” or “frame” stories, in which a tale is told within another tale, which is told within another tale, sometimes for multiple levels, like Russian nesting dolls.

This fascinated me. I’ve always looked for ways to create an illusion of depth and antiquity in the Tufa novels, to give a sense of the Tufa’s immense past. I decided that the first section would be modern, but was less clear on the second one, which would be a story that one character tells others. I knew it had to take place in the past, but how far back should I go? And around what concept should I base it, so that it works both as part of the overall novel, and on its own as a story?

This fascinated me. I’ve always looked for ways to create an illusion of depth and antiquity in the Tufa novels, to give a sense of the Tufa’s immense past. I decided that the first section would be modern, but was less clear on the second one, which would be a story that one character tells others. I knew it had to take place in the past, but how far back should I go? And around what concept should I base it, so that it works both as part of the overall novel, and on its own as a story?

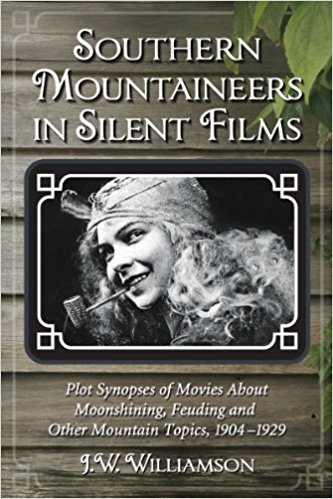

Sometimes if you leave yourself open to ideas, then they’ll just drop in your lap. And in this case, during a visit to Frugal Muse in Madison, WI, I came across Southern Mountaineers in Silent Films by J.W. Williamson.

This is not a typical history, or even a critical consensus. It’s simply a collection of “Plot Synopses of Movies about Moonshining, Feuding and Other Mountain Topics, 1904–1929,” as the subtitle explains. Williamson told me over e-mail that it was “a footnote that got out of control” to his book, Hillbillyland: What the Movies Did to the Mountains and What the Mountains Did to the Movies.

There’s an introduction to put things in context, and it’s fascinating. Between the dates covered by the book (1904-1929), at least 476 movies were made about mountain folk, primarily set in Appalachia and the Ozarks.

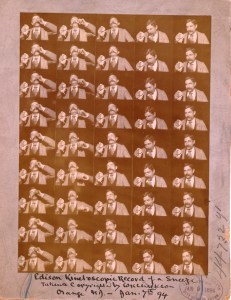

The Library of Congress paper print of Fred Ott’s Sneeze, 1894.

Most of these are lost due to the decay of their nitrate film. However, a few remain thanks to the practice of making physical paper prints of each frame of film in order to register the copyrights. As a result, the earliest film mentioned in the book, 1904’s The Moonshiner, can still be seen:

One of the compelling details of this initial “mountain” film is the utter lack of any expected “hillbilly” cliches. Note that the titular moonshiner wears a fedora and tie, and that one daughter sports a nice dress and hat. There’s also no doubt that the film sides with the moonshiners, not with the revenue agents hunting them. It’s primitive filmmaking, but fairly sophisticated storytelling.

The well-dressed moonshiner, circa 1904.

So with this amazing look into a world I barely knew about, I found the concept for my second-level story. I created a fictional filmmaker and sent him to my imaginary coal-mining town, where his intent to capture “reality” gets sidetracked by his encounter with The Fairies of Sadieville.

Which you can pre-order here.

March 26, 2018

Finding the rhythm of another time and place

While revising The Fairies of Sadieville (available in two weeks!), my editor pointed out that some dialogue, for a subplot set in prehistory, sounded a bit too “modern.” When I stepped back and looked at it objectively, I had to agree. I had these primitive people speaking with the cadences, and more importantly in the syntax, of modernity. It was deliberate, since as always, I don’t want to put barriers between the characters and the reader. That didn’t mean, however, that it worked.

While revising The Fairies of Sadieville (available in two weeks!), my editor pointed out that some dialogue, for a subplot set in prehistory, sounded a bit too “modern.” When I stepped back and looked at it objectively, I had to agree. I had these primitive people speaking with the cadences, and more importantly in the syntax, of modernity. It was deliberate, since as always, I don’t want to put barriers between the characters and the reader. That didn’t mean, however, that it worked.

To revise it, I had to figure out just how people in this ancient time period would talk. I’m not talking about creating a language; it’s more a matter of rhythm.

In Charlton Heston’s autobiography In the Arena, referring to the script for Ben Hur, he says:

“Willy (director William Wyler) persuaded English poet/playwright Christopher Fry to come to Rome. […] His changes were seldom structural, but almost always stylistically crucial, such as changing ‘You didn’t like the food?’ to ‘The meal did not please you?’ (Not a trivial difference; the first is inescapably twentieth century, the second acceptably period.)”

When it comes to inhabiting history, I bow to Heston’s experience: the man played Moses, Andrew Jackson and Michelangelo. And when it goes wrong, you get this, written by Oscar Millard, delivered by John Wayne(!) as Genghis Khan(!!) in The Conquerer:

“She is woman – much woman. Should her perfidy be less than that of other women?”

So, there are my extremese: as good as Ben-Hur, not as bad as The Conqueror. But I’m neither Christopher Fry nor (thank goodness) Oscar Millard. I couldn’t mimic their styles. And I still believed that my guiding idea, to keep stylistic choices from getting in between the readers and the characters, was a good one.

So, how do you do it? Is it a matter of style, as Heston postulates? Or is there a deeper challenge?

When I first wrote this section of The Fairies of Sadieville set in the prehistoric past, I decided deliberately to give the dialogue a contemporary rhythm. I reasoned that, to the ancient people who spoke it, that’s how they would perceive their own language. Also, it made it easier for the contemporary reader; just as Shakespeare’s language can distance the reader or playgoer from the story, trying to write in a faux ancient style can seem precious, twee, and/or off-putting. I definitely wanted to avoid that.

And yet my editor has repeatedly proven that her suggestions are often spot-on and crucial, so I went back and rethought my approach. In short order, I discovered the problem: I had considered the context of this section of the book, but not its context in the novel as a whole.

There are three time periods represented: the modern world, 1915 America, and this prehistoric section. Obviously the modern world is easiest, and the 1915 world wasn’t much harder (although I did spend a great deal of research time tracking down when particular slang terms and sayings came into common use). But since the prehistoric section deliberately takes place before accepted paleontology says humans even existed, and involves fictional races of people, they really did need to speak differently.

The best popular example of a character speaking differently, but remaining comprehensible, is Yoda in the Star Wars films. Lawrence Kasdan, who scripted Yoda’s first appearance in The Empire Strikes Back, said in the annotated script:

The best popular example of a character speaking differently, but remaining comprehensible, is Yoda in the Star Wars films. Lawrence Kasdan, who scripted Yoda’s first appearance in The Empire Strikes Back, said in the annotated script:

“I remember that George had a feeling about the kind of speech he wanted Yoda to have. It had to do with inversion and with a kind of medieval feeling with religious overtones. Once we figured that out, it became very logical to have Yoda say, ‘Good it will be…’ Inverting everything did the trick.”

And it works, so much so that his cod philosophies have been taken as genuine spiritual insights by way too many people. “Do. Or do not. There is no try,” is probably the worst advice ever, and a nightmare when you’re trying to explain the concept of perseverance to your children. But I digress.

I regrouped and approached the language as English shorn of its later cultural quirks. After all, in the novel it’s a story being told, not an accurate literal transcription of events. In rhythm and a few bits of slang, I emulated the dialects of Great Britain, semi-implying that they originated with my fictional people. I cut vast swaths of text showing how characters learned each other’s language (I wasn’t writing anthropology, after all) and tried to focus on simply serving the narrative, not these linguistic tangents.

Does it work? You’ll have to decide. You can pre-order The Fairies of Sadieville here.

March 19, 2018

Dark as a Dungeon: the music of the miners

Part of The Fairies of Sadieville takes place in 1915, and involves two specialized occupations: making silent movies, which I’ll cover elsewhere, and coal mining. Sadieville is a new coal boom town, and I was determined to get it right. I did a lot of book research on it, to get accurate technology and terminology, but to get the feel, I turned, appropriately, to music.

Part of The Fairies of Sadieville takes place in 1915, and involves two specialized occupations: making silent movies, which I’ll cover elsewhere, and coal mining. Sadieville is a new coal boom town, and I was determined to get it right. I did a lot of book research on it, to get accurate technology and terminology, but to get the feel, I turned, appropriately, to music.

The quintessential coal-mining song is “Sixteen Tons,” written in 1947 by Merle Travis but performed definitively by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1955. Everyone knows the first part of the chorus (adapted from a letter written by Travis’s brother John):

You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt.

It captures, in those fifteen words, the quintessential dilemma of the coal miner: working long hours with no safety gear or precautions,and paid in company scrip that could only be used at the company store. Since there was never enough pay to cover all the bills (also sent by the company), the miners ended up in debt to their employer. The second couplet of the chorus (from something said by Travis’s father) delivers the coup de gras:

Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store.

As part of the creative process, I listened to a lot of vintage country music that dealt with mining, most of it depressing, all of it dripping with authenticity. Like drinking, a life of hard and meaningless work is something country music is tailor-made to address. But by far my favorite collection is Dark as a Dungeon: Songs of the Mines, a 2010 compilation from Rebel Vault Masters. Ironically released less than a week prior to the the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster, which killed 29, it musically depicts the trials, despair, and rare joys of the mining life.

The title, and the title song, also come courtesy of Merle Travis, and once again the chorus gives a perfect capsule summary of the miner’s lot:

And it’s dark as a dungeon and damp as the dew

Where danger is double and pleasures are few

Where the rain never falls and the sun never shines

And it’s dark as a dungeon way down in the mines.

The CD Dark as a Dungeon concludes with this song, performed by James Alan Shelton. Some other gems include Larry Sparks performing Randall Hylton’s “Digging in the Ground,” a song about the effect of mining on a once close-knit community; Keith Whitley and Ricky Skaggs’ version of the classic “Dream of a Miner’s Child”: and Roy Dockery’s “Daddy’s Dinner Bucket,” performed here by Ralph Stanley II.

In an e-mail, the album’s producer, Dave Freeman, told me, “It turned out to be an easy topic to form an album around, as there was a healthy grouping of both old traditional songs like ‘Dream of a Miner’s Child,’ some items from the 1940s and 50s like ‘Dark as a Dungeon,’ and some quite new material like the David Davis song [‘The River Ran Black’].”

He added, “I can only guess why the subject has an appeal for many (especially many people from the mining regions of West Virginia, Kentucky, and Virginia and other areas of Appalachia): because of the immediacy and reality of the subject, and the finality of life for so many of those who inhabit the mining regions. For those on the ‘outside,’ the subject is likely one of a fascination with miners and mining rather than a mere interest.”

These songs were my way into the heads of the miners, storekeepers, company men and hired law that were common at the time the story is set. Although the novel isn’t really about them, they deserve to be depicted as fully and accurately as possible, and I hope I’ve done that. For too long, workers like these were denied even basic human dignity; if nothing else, I wanted to make sure I took no more of it away.

If you have a favorite mining song, please let me know in the comments.

The Fairies of Sadieville will be released April 10; it’s available from all the usual suspects.

March 12, 2018

Why fairies?

One of the most basic questions I get about the Tufa series, which concludes in April with The Fairies of Sadieville, is also one of the hardest to quantifiably answer:

One of the most basic questions I get about the Tufa series, which concludes in April with The Fairies of Sadieville, is also one of the hardest to quantifiably answer:

Why fairies?

It certainly wasn’t an obvious interest. I grew up in a tiny Southern town, surrounded by friends and family who had no time for matters of imagination. And even my tastes ran more toward the science fiction of Star Trek and Star Wars than, say, the fantasies of Middle Earth. The classic “fairy tales” held no interest for me, and thanks to my interest in Sherlock Holmes, the only bit of fairy folklore I knew was that the “Cottingley Fairy” hoax fooled Arthur Conan Doyle.

But it seems the fairies, as befits those also known as “Longaevi,” were content to wait for me to complete my long and circuitous route to find them.

Twenty years ago, I first attended the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, TN (you can read my friend Magda’s account of that visit here). Jonesborough looms large in the Bledsoe family; my father’s people all came from the area, and when I visited, I discovered Bledsoes everywhere, including alderman and future mayor Tobie Bledsoe. More, many of them (like artist Bill Bledsoe) worked in creative fields, something none of my father’s immediate family ever did (or had much patience with).

After a long day of hearing a wide variety of stories, I, Magda and the rest of our group found ourselves in a downtown pub, listening to some of the storytellers jam (many of them are also musicians). At about two in the morning, the musicians, led by Jennifer Armstrong*, led us into the deserted main street for some contra dancing. The exhaustion, elation, sweat and sense of community fell into place in my head (and heart), and I felt a genuine, organic sense of magic that I knew I wanted to somehow capture and share.

After a long day of hearing a wide variety of stories, I, Magda and the rest of our group found ourselves in a downtown pub, listening to some of the storytellers jam (many of them are also musicians). At about two in the morning, the musicians, led by Jennifer Armstrong*, led us into the deserted main street for some contra dancing. The exhaustion, elation, sweat and sense of community fell into place in my head (and heart), and I felt a genuine, organic sense of magic that I knew I wanted to somehow capture and share.

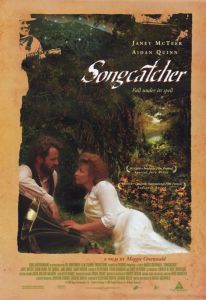

Shortly after this, I first saw Maggie Greenwald’s film Songcatcher, about a musicologist traveling the Appalachian mountains in 1907 in search of songs brought over from Europe. Although the character of Lily Penric is fictional, she’s inspired by a real woman, Olive Dame Campbell. In another coincidence, Aidan Quinn plays mountaineer Tom Bledsoe, possibly the only time a potential relative of mine has been portrayed in a film. (I should note this film is not related to the Sharyn McCrumb novel The Songcatcher, which I did not read until many years later. It’s also excellent.)

Shortly after this, I first saw Maggie Greenwald’s film Songcatcher, about a musicologist traveling the Appalachian mountains in 1907 in search of songs brought over from Europe. Although the character of Lily Penric is fictional, she’s inspired by a real woman, Olive Dame Campbell. In another coincidence, Aidan Quinn plays mountaineer Tom Bledsoe, possibly the only time a potential relative of mine has been portrayed in a film. (I should note this film is not related to the Sharyn McCrumb novel The Songcatcher, which I did not read until many years later. It’s also excellent.)

The last piece of the puzzle were the stories I heard growing up about a group of people known as the Melungeons. The stories themselves were, unfortunately, typical (and fairly racist) boogeyman tales similar to the ones I also heard about black people and Native Americans, but one detail stuck with me: the claim that the Melungeons were there when the first European settlers arrived, and that no one—perhaps not even them—knew where they came from.

There was no overt connection to fairy lore in any of these sources. But when I researched the music of the region, it led me back to the Celtic ballads that had also emigrated to America. In researching those, I discovered how much the rich background of fairy lore informed both the music and the culture of the people who, ultimately, settled the Appalachians.

And so, when I needed a central conceit to pull together all those disparate elements–history, music, landscape–I found the Other Crowd. Or did they find me?

What led to your interest in fairies?

*Bliss Overbay’s snake tattoo is inspired by Jennifer’s.

March 5, 2018

“Sadieville” and The Fairies of Sadieville

I’ve written about the music of the Tufa novels many times, from many different perspectives. The songs quoted in the text tend to be classic public domain folk songs, or songs written by musicians who have given me permission to use them. I have on occasion written lyrics myself (most extensively in Wisp of a Thing), but I make no claim to be a songwriter. And in Gather Her Round, for the first time I had an original song written specifically for the novel by Jen Cass and Eric Janetsky (a.k.a. the Lucky Nows): “Against the Black,” which will be available on their forthcoming debut album. But here, I want to talk about the song “Sadieville,” which inspired the title for The Fairies of Sadieville.*

I’ve written about the music of the Tufa novels many times, from many different perspectives. The songs quoted in the text tend to be classic public domain folk songs, or songs written by musicians who have given me permission to use them. I have on occasion written lyrics myself (most extensively in Wisp of a Thing), but I make no claim to be a songwriter. And in Gather Her Round, for the first time I had an original song written specifically for the novel by Jen Cass and Eric Janetsky (a.k.a. the Lucky Nows): “Against the Black,” which will be available on their forthcoming debut album. But here, I want to talk about the song “Sadieville,” which inspired the title for The Fairies of Sadieville.*

All the Tufa novel titles come from the songs of Jennifer Goree, which you can read about here. But in all those books, I’ve never used an actual song by Jennifer. The Fairies of Sadieville remedies that, quoting the song “Sadieville,” from her second album Don’t Be a Stranger, as a recurring motif.

All the Tufa novel titles come from the songs of Jennifer Goree, which you can read about here. But in all those books, I’ve never used an actual song by Jennifer. The Fairies of Sadieville remedies that, quoting the song “Sadieville,” from her second album Don’t Be a Stranger, as a recurring motif.

Not that I’ve deliberately avoided using her songs; it’s just that the prior novels really had no place for them that didn’t seem forced, or arch, or even twee. The cool kids call it a “Title Drop.” But “Sadieville,” and its place in The Fairies of Sadieville, is different.

First, the song itself is a haunting, tender, and mournful ballad, which perfectly suits the novel’s tone. It captures the ache of loss with beautiful simplicity. If you didn’t know it was a recent, original song, you might truly believe it came over with the original Scotch-Irish settlers. Listen for yourself:

Me with Jennifer Goree, Greenville, SC 2016

Second, there was simply no other song that would fit, and had Jennifer turned down its use (thank you again!), I would’ve had to start over from scratch with a completely different story. The song is this novel’s soul, in effect a mantra tying together varied threads of history. I mentioned its beautiful simplicity above, and that’s true; but achieving that is almost never simple, and it demonstrates Jennifer’s amazing songwriting.

I’ve often called Jennifer “the Tufa muse,” and it’s not an exaggeration. Her music was there as I first developed the ideas, and her kindness in letting me use her song titles for my novels is, for me, like a blessing on the whole process. Without her, I don’t know what I would’ve titled The Hum and the Shiver; I do know that Wisp of a Thing would’ve had the much more unwieldy title Ballad of the Forever Girl.

I’ve often called Jennifer “the Tufa muse,” and it’s not an exaggeration. Her music was there as I first developed the ideas, and her kindness in letting me use her song titles for my novels is, for me, like a blessing on the whole process. Without her, I don’t know what I would’ve titled The Hum and the Shiver; I do know that Wisp of a Thing would’ve had the much more unwieldy title Ballad of the Forever Girl.

And without her song “Sadieville,” The Fairies of Sadieville would not even exist.

Currently Jennifer performs with her group Thermonuclear Rodeo in and around Clemson, SC. Keep up with her on Facebook here.

*originally the book, like the song, was just called Sadieville. My editor, quite sensibly, pointed out that since there’s a real town in Kentucky called that, casual readers might think it’s about that place, or maybe a travel guide. Hence the more explicit title.

February 28, 2018

Death Wish, Old and New

After seeing commercials for the upcoming Eli Roth remake, I rewatched the original Death Wish from 1974. I was really surprised by how different Death Wish was from what I remembered, and how Roth’s remake, to judge from the trailers, totally misses the point. Yes, Charles Bronson becomes a vigilante after his family is brutally attacked, but that’s just the skeleton of the story; the muscle and viscera derive from the specifics of crime-ridden 1970s New York, and the politics of the film’s vigilantism.

For starters, and the biggest surprise: Bronson doesn’t seek the specific hoods (one played by Jeff Goldblum) who assault his wife and daughter; once that really unpleasant scene is over, they’re never seen again. Instead, Bronson shoots any mugger who approaches him. He goes out of his way to be in dangerous places, flashing wads of cash in bad neighborhoods, until you realize that the “death wish” of the title doesn’t apply to criminals, but to Bronson himself. He’s courting death as a way out of his pain and helplessness.

Further, the cops, even once they know he’s behind all these deaths, don’t rush to stop him. Not only has the anonymous vigilante become a folk hero and media darling, but he’s actually brought the crime rate down. If they stop him, and it goes back up, the public will realize how useless the cops really are. New York City in the 70s was notoriously dangerous, with a reputation similar to the one Chicago has today. It was a time when confidence in authority, any authority, was crumbling, and the depiction of the police tapped directly into that.

So, if you can believe it, this is a fairly subtle film. Bronson, an actor who I’ve only recently begun to appreciate as more than just a granite face, is very good. In his early fifties, rocking the pencil-thin mustache and shaggy 70s hair, he never seems like a cliche “man of action; after his first kill, in fact, he runs home and throws up. Director Michael Winner, who made a lot of crappy movies interspersed with some gems (his first film with Bronson, Chato’s Land, is a pretty blatant Western metaphor for Vietnam, with a great supporting cast), carefully stays just this side of parody and black comedy, and takes his time establishing just who the Bronson character is before the carnage starts.

The trailers for Eli Roth’s remake look far less interesting, and considering the state of the world, jaw-droppingly tone deaf. Bruce Willis explicitly goes after his wife’s killers, quipping and killing to the strains of AC/DC. Considering the contemptible Roth’s previous films, and Willis’s innate insufferable smugness, it seems likely this is a mere standard revenge film, more in line with all the lesser Death Wish sequels.

The crime film peaked in the 70s, as evidenced by The French Connection, The Seven-Ups, Shaft, the first two Godfathers, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, and so many others. Death Wish fits perfectly in this company, a dark examination of society’s failures and the morality of vigilantism. It’s not always a pleasant film, but it’s more than popular memory seems to make of it.

Avoid the sequels, though. They all suck. And consider Roth’s vile, nihilistic prior films (Hostel 1 & 2, Green Hell) when you decide whether to see his new Death Wish.

February 26, 2018

Interview: Sean Grigsby, author of SMOKE EATERS

Dragons are ubiquitous, and as a result, it can be difficult for a writer to find a new way to present them. Sean Grigsby, a fellow west Tennessean, has found a great approach: he combines dragons with his own experiences as a firefighter in his first novel, Smoke Eaters. I was lucky enough to read an advance copy of it, and Sean was kind enough to answer some questions about it.

Your protagonist is no spring chicken; in fact, he’s on the verge of retirement when the story starts. Why did you go this route instead of the more typical handsome young hero?

The short answer is: it’s been done to death. I wanted to do something different.

I also hadn’t seen an older protagonist since Old Man’s War. When I came up with the idea for the book, I myself was back in fire academy again, even though I had gone through it five years before. I’d moved to a bigger city department and, although I had all the credentials, I had to prove myself all over again because that’s what they required. For Smoke Eaters, I wanted to see how someone with a full career behind him, and experience as an officer, would deal with having to start all over as a rookie. It created a lot of funny moments. Brannigan takes no crap.

Do you consider Smoke Eaters fantasy, or science fiction?

Both! You could call it future fantasy or science fantasy if you had to put a label on it.

I couldn’t live in a world where I could only choose vanilla or chocolate when I could have swirl. And look at all the zany things Ben & Jerry’s comes up with. I’m very eclectic in my reading, and I love mixing genres and tropes together in my writing. I’m a total pantser and, with Smoke Eaters, it was even more so. I really let my imagination take the reins.

The premise of firefighters vs. dragons was established, but I placed it in the future for a few reasons. The awesome laser weapons and power suits in Smoke Eaters are much better tools for fighting dragons than what I have on my fire truck right now. The robots, besides being a physical threat, are also taking everyone’s jobs and I liked examining that. There are people today who believe this is a real possibility. Setting it in the future opened up a whole lot of fun and crazy technology to sprinkle throughout, especially when the smokies go to Canada. Also, Ray Bradbury is someone I look up to as a writer and he had his vision of firefighters in the future. Smoke Eaters is mine.

The wraiths were a complete surprise, even though I open with one floating over the ashen wastes of Ohio. I saw this image in my mind and I just went with it. But of course, the dragons are the stars of the show.

What fictional dragons were your favorites?

Smaug has always been an awesome villain to me. Dragons are dangerous enough as it is. Add sentience and speech, and they’re nearly unstoppable.

How did you come up with your conception of dragons?

A lot of fantasy books show dragons to be friends, pets, or transportation. I didn’t want to do that. My dragons are mean, terrible bastards and range in size, shape, and deadly attacks like toxic gas and electric shock. They’re animals for sure, but they’re driven by a desire to burn, eat, and mate with abandon. They’ve been hibernating underground for centuries, sort of like cicadas, and now they’re back, burrowing up from the ground and burning things down to make their ash heaps and lay their eggs.

It’s been seven years since E-Day, the day the first dragons emerged, but people are still getting used to living with the threat. The dragons are a metaphor for fire, and in my own profession, every fire is different. It’s one of the aspects I love about being a firefighter, but it also makes it very important to be vigilant for the unexpected.

My dragons throw a ton of unexpected at Brannigan and the other smoke eaters.

Outside of your own book, of course, what’s your favorite depiction of fictional firefighters?

Rescue Me is definitely my favorite, and probably the most accurate. We’re still human beings, and deal with a lot personal issues on top of all the terrible things we see on the job. Plus, they got the firehouse humor right.

Backdraft, while being one of my favorite movies as a kid, gets a lot wrong. It’s insane. No, one cannot see clearly in a structure fire. It’s filled with dark smoke. And I’m all for attacking a fire aggressively, but holy hell did they do some dumb things that would get anybody killed within seconds. But that’s Hollywood.

Ladder 49 is okay, and pretty accurate. But damn, it’s sad.

Chicago Fire is probably my least favorite. Very inaccurate, and I want to make it clear that we do not have sex with our significant others or do drugs while at the firehouse. That’s a quick trip out the door. We have to be professional.

What was your favorite real-life firefighting detail that you slipped into the story?

The fire science is all true to fact.

One recent reviewer said a favorite scene was when the smoke eaters get a false call for what is clearly not a dragon. I’ve responded to really dumb non-emergencies. A lot of it is just annoying, but every once in a while, they are some of the funniest and strangest experiences of my life.

The biggest detail from my real-life experience is the camaraderie and firehouse humor. I used a few lines I’ve heard people say around the job. We also really call each other “dub” like Brannigan and his firefighters do. I have no idea where the term of endearment came from. I heard that my fire brothers and sisters tracked down the oldest living retired firefighter at our department and he said that the term had been around long before him.

The fire service is big on tradition, and sometimes we have no idea where the traditions came from.

Smoke Eaters is available March 6 from Angry Robot Books. You can pick it up from all the usual suspects.

Sean Grigsby is a professional firefighter in central Arkansas, where he writes about lasers, aliens, and guitar battles with the Devil when he’s not fighting dragons. He hosts the Cosmic Dragon podcast and grew up on Goosebumps books in Memphis, TN.

Sean Grigsby is a professional firefighter in central Arkansas, where he writes about lasers, aliens, and guitar battles with the Devil when he’s not fighting dragons. He hosts the Cosmic Dragon podcast and grew up on Goosebumps books in Memphis, TN.February 19, 2018

On Fairy Life

This is the second post adapted from a presentation I did at the 2017 Pagan Unity Festival. You can read the first post here.

As I said in the prior post, if you’re here reading this, you probably already know that my Tufa novels are about a race of exiled fairy folk in the mountains of east Tennessee. The title of the sixth and final book in the series, The Fairies of Sadieville, explicitly references this connection. And although they’re entirely fictional, they draw on fairy folklore and address some of the fundamental questions about fairy belief.

As I said in the prior post, if you’re here reading this, you probably already know that my Tufa novels are about a race of exiled fairy folk in the mountains of east Tennessee. The title of the sixth and final book in the series, The Fairies of Sadieville, explicitly references this connection. And although they’re entirely fictional, they draw on fairy folklore and address some of the fundamental questions about fairy belief.

Director Howard Hawks, speaking (in the book Hawks on Hawks) about one of his few flops, the 1955 movie Land of the Pharaohs, pinned its failure on a simple issue: “We didn’t know what a pharaoh did.” In his world view, people are defined by what they do, not who (or what) they are.

So, assuming fairies have an objective reality–that is, they exist independently of those who encounter them–it begs the question, what do they do?

What size are fairies?

What size are fairies?

C.S. Lewis points out that, before Gulliver’s Travels, the relative size of various beings was never a serious concern, or even portrayed with any type of consistency. Therefore, we can’t be sure how large or small the ancients considered the fairy folk to truly be.

As the Christian religion advanced, fairies were considered evil by default, but since many artists and poets wished to write about them, they made them first playful, then physically so small they were considered no threat, and then so innocent and insubstantial they appealed only to children.

What do fairies look like?

For the most part, fairies look like people. The Tuatha De Danaan are generally depicted as tall, red haired and blue eyed, much fairer than the dark people who lived in Ireland and Scotland.

Depictions of fairies with wings only appeared around the time of the Industrial Revolution. As stated above, fairies in general grew smaller, more child-like, and as nature spirits were relegated to gardens, where they took on the characteristics of insects (wings and attraction to flowers).

What do fairies do?

In folklore, fairies seldom seem to have an actual trade. Like the monied class, they spend most of their time doing frivolous things like gaming, dancing, playing music or simply frolicking.

They can be generous with their time and skills, helping humans with menial tasks. But there are elaborate strictures around this generosity. They are easily offended by what humans consider minor impoliteness, or even by politeness presented in the wrong way.

This folkloric requirement may be a result of two concepts colliding: the idea that ancient fairy folk were gods, or at least mighty warriors, banging up against the later Christian concept that they are satanic simply by being remnants of pre-Christian beliefs. The warriors become cranky sprites, their battle rage minimized and simplified into being sticklers for etiquette.

What do you call fairies?

Many folkloric creatures have survived into modern times: vampires, werewolves, angels, demons, etc. But few are as touchy as the fairy folk, to the point that even speaking about them is dangerous. To call them by their name is to invite their ire.

Among the many terms used for them:

Good Folk

Wee Folk

Good Neighbors

Good People

Greencoaties

The Grey Neighbors

The Gentry

The Fair Folk

The Shining Ones

The Kindly Ones

And my favorite,

The Other Crowd.

The implication from this is that they are simply looking for an excuse to bring down drama on unsuspecting heads. Is that, then, what fairies do?

In his final book, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature, C.S. Lewis refers to fairy folk as the Longaevi, meaning “longlivers.” He placed them in their own classification, because they just didn’t fit anywhere else.

Modern Fairy Encounters

Fairy sightings have not diminished with the advent of modern civilization. Computers, the internet, and cell phones have neither proven nor disproven their existence. Just like Nessie, Bigfoot, and other possibly mythical beings, fairies are still being seen. The three books pictured with this post (Faery Tale, Seeing Fairies, and Meeting the Other Crowd) all deal with contemporary encounters. There are documentaries about modern encounters, such as The Fairy Faith.

Why?

If we accept that fairies are real, then they’re being seen because they’re there. But if they have that objective reality, why do we see the Victorian-style fairy, and not the ancient warrior gods of the Celts? What exactly are we seeing?

If they’re purely mental phenomena, what do they represent to us that makes our brains keep conjuring them? And why do we conjure them in this fairly specific, homogenous Victorian form?

C.S. Lewis sums it up nicely:

“As long as the fairies remained at all, they remained evasive.”