Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 3

November 5, 2018

Mount Horeb’s Psychic Boy…or Not

When you’re an author of fantasy and horror, and you live in a small town like Mount Horeb, Wisconsin, it’s inevitable that you get requests like the one I recently received from our library director, Jessica:

“I have a spooky question for you.”

She presented me with a badly-faded microfiche printout (see above) of a news story from 1909, about a psychic boy, Henry James Brophy, right here in Mount Horeb. It turned up in an old box at the library, put there and forgotten who knows how long ago. And the story included the picture of an old-style house. Jessica wanted to know if it was what I jokingly called “the murder house,” an abandoned home I’ve been passing for ten years when I walk my kids to school (and which must have a good story of its own).

[image error]

The “murder house” (okay, not really, but doesn’t it look like it could be?)

It wasn’t, but I was intrigued nonetheless. Mount Horeb is wonderful, warm, and welcoming: the last place you’d expect a psychic boy to turn up, and if one did, the last place you’d expect it to be either hidden or forgotten. More than likely, if the house still existed (and it might: my own house is over 100 years old), it would have turned into local lore: “Oh, yah, that’s where that boy lived who could make things fly around, doncha know.”

[image error]

The no-longer-extant house where the strange events occurred (thanks to the Mount Horeb Historical Society).

The microfiche was so faded it was almost unreadable, yet I could make out just enough to set the hook in me:

“… the nine-day wonder of the town has already outlived its proverbial span…”

“… a child that would be noticed in a crowd because of a certain flower-like beauty…”

“…the boy’s grandfather became nearly distracted with terror…”

And then there were the odd details:

“… pieces of soap seemed particularly sensitive to the diabolic influence…”

“…the house had been equipped with electric lights and telephones and it was thought perhaps the house had become ‘electrified,’ causing the disturbances…”

The whole story, in fact, is over 2,200 words long, quite lengthy for a front-page newspaper article. Clearly the author (listed only as “staff correspondent”) had leeway to put in as much detail as he or she wanted.

Since reading it would be a difficult and slow process, deciphering both the faded text and the idiomatic language of the time, I volunteered to transcribe the article as I went so that there would be an easily readable copy. And as soon as I sat down to begin, I found an obvious clue that put the whole thing in a new perspective.

The story of Henry James Brophy appeared in the Madison-based Wisconsin State Journal on April 1, 1909. April Fool’s Day.

Ah, well. I went ahead and transcribed it, finding a fascinatingly detailed story that someone had put a lot of work into, whether it was true or not. By the time I finished, I admired this “staff correspondent” as a writer, if not a journalist.

Now, as a former journalist myself, I knew not to accept anything at face value. Yes, this was probably an elaborate April Fool’s joke, but you never know. So I poked around some more.

[image error]

Henry James Brophy as a boy (courtesy of the Mount Horeb Historical Society).

There were stories in the Waterloo, Iowa paper The Courier, dated June 11, 1909, and the Washington, D.C.(!) Evening Star on May 16, but both merely rehashed that original story, in some cases reprinting passages verbatim. The thing that kept me going was a follow-up story on April 2 in the Wisconsin State Journal, interviewing skeptical figures from the University of Wisconsin. Why do a follow-up to an April Fool’s joke?

So I visited the Mount Horeb Historical Society, and found out they had a whole file on this, as well as pictures of the house and the alleged psychic boy. It confirmed that the story was no April Fool’s joke, and certainly some people in Mount Horeb believed something supernatural was afoot (there were, of course, plenty who believed it was all a sham).

In 1978, Madison’s Capital Times published a legitimate follow-up on October 26 (just in time for Halloween); reporter Gary Peterson tracked down witnesses to the original events. Many were already dead, but a few provided memories, such as these elderly siblings:

“It was all a fake…he [Henry Brophy] used to take a spool of thread and roll it down the stairs.”–Josie Evans

“His nickname was Spoolix.”–Jake Evans

Or Jan Krogen, who said, “We started keeping a log and it got us kind of spooked. […] The strange coincidences and things that happened all let up after a year.”

In 1980, Michael Norman and the late Beth Scott included the story in their first edition of Haunted Wisconsin. They retold the story, but provided nothing new; like so many others, they seemed to draw their information entirely from that initial April 1, 1909 story and its April 2 follow-up.

So apparently something did happen in 1909, and made enough of an impression that people recalled it 70 years later. Was it genuine psychic phenomena? As with so many alleged psychic events, there’s simply no way to know. Stories like this live on because they’re unusual and unique, and any attempt to explain them away, however well-intentioned, is often resisted because it means that there’s a little less wonder in the world.

Let me know in the comments if you’re interested in reading the text of the original article; if enough people are, I’ll post it.

(Thanks to the Mount Horeb Public Library and the Mount Horeb Historical Society for their help.)

October 17, 2018

Review: Vampire Classics (Graphic Classics #26)

It’s no secret that I love me some vampires. I’ve even written two vampire novels of my own, Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood. Their combination of danger coupled with intelligence, of being able to pass as one of us until the fangs finally come out, makes them the perfect monster. They can be used to represent literally everything from repressed minorities to disease victims to the devil himself. They can literally become anything we need them to be.

That’s why this 26th volume of the Graphic Classics series, Vampire Classics, was right up my dark, gaslit alley. From the silent film Nosferatu to Ray Bradbury’s “The Man Upstairs,” the stories chosen for adaptation rescue some of the best vamp lit from their dusty mausoleums and put the blood back in their veins.

For those unfamiliar with it, Nosferatu is a 1922 German silent film adapted (without permission) from Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula. Even today, many critics consider it the best vampire film ever, and if you catch me on the right day, I’ll agree with them. Its depiction of Count Orlock (aka Dracula) as a pale, bald fiend with two rat-like fangs is such a seminal image, it was used in both the first adaptation of Stephen King’s ‘Salem’s Lot and the recent New Zealand comedy What We Do in the Shadows. Here the artist (Craig Wilson) finds a middle ground between the film’s indelible black and white images and the full-color palette available to comics. The adapter (Tim Lasiuta) also finds a good meeting point between the film’s decidedly European feel and a more typically urgent American one. It strikes me as a good compromise between marketing necessity (anything called Vampire Classics must deal with Dracula, after all) and the chance to give lesser-known stories their space.

Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan, sets “The Horror from the Mound” in his native Texas, with a virile cowboy hero who is the very antithesis of Stoker’s fainting Victorian dandies. It ends, naturally for that most manly of pulp authors, in a fistfight between rancher and vampire, and the art (by Timothy Truman) is done entirely in sepia, capturing the tone of the wide, dry prairie.

Ray Bradbury’s “The Man Upstairs” is illustrated (by Rick Geary and colored by Benjamin Wright) in a fittingly bright, childlike way, reflecting both the young boy protagonist and the story’s metaphor of bright panes of colored glass. Editor Mort Castle adapts his own story, “What Is,” illustrated in a semi-sepia way to reflect not just the past, but the lives of those trapped in poverty and despair. “The Flowering of the Strange Orchid” by H.G. Welles is not strictly a vampire story, but the illustrations by Shepherd Hendrix perfectly capture its Edwardian setting.

“Dracula’s Guest” is popularly considered the original opening chapter of Stoker’s novel, although the differences in the final version make that hard to reconcile. It’s also the story I know best, and Ronn Sutton’s artwork depicts it pretty close to the way I’d always imagined it. He gets the atmosphere, and the sense of an otherworldly European location, exactly right (I love the details on the soldiers’ uniforms).

Finally, “Olalla” by the great Robert Louis Stevenson is, like the Welles tale, only tangentially a vampire story, but the page illustrating (courtesy of Reno Maniquis) the single vampiric attack might be the strongest in the whole book. It also made me look up the word, “tatterdemalion.” It ends the volume on an appropriately melancholy note.

The Graphic Classics series is produced by Tom Pomplun in Wisconsin close to where I live, and has amassed an international reputation for its variety, matching story and artwork in unexpected and often startling ways. This latest edition is no exception, and suitably for the Halloween season, it’s a delightful visit with those children of the night.

October 8, 2018

The Vampires Want to Wear My Mud Shoes

One of my personal traditions is that, every October, I re-read Bram Stoker’s Dracula. It’s such a rich novel that I usually find at least one detail I’d never noticed before. This year, though, in addition to reading the actual novel, I’ve been reading a children’s version to my daughter (after all, what else can follow Frankenstein?).

It’s easy to mock these child-friendly versions of favorite stories, particularly when the original was plainly written for adults. But to me, they serve an important purpose. They familiarize kids with the basic plots of classic literature, so that later when they encounter the originals in school, they don’t have to wade, blank-eyed with incomprehension, through dense, often outdated prose (I’m looking at you, Silas Marner). It’s easy to mock some of these (there’s even a kids’ version of Moby Dick that has “Call me Ishmael” as the second line, which I wrote about here), but I’ve always enjoyed reading them aloud to my kids. (For insight into the process of writing these, see my interview with Tania Zamorsky, who also wrote a kids’ version of Dracula, here.)

It’s easy to mock these child-friendly versions of favorite stories, particularly when the original was plainly written for adults. But to me, they serve an important purpose. They familiarize kids with the basic plots of classic literature, so that later when they encounter the originals in school, they don’t have to wade, blank-eyed with incomprehension, through dense, often outdated prose (I’m looking at you, Silas Marner). It’s easy to mock some of these (there’s even a kids’ version of Moby Dick that has “Call me Ishmael” as the second line, which I wrote about here), but I’ve always enjoyed reading them aloud to my kids. (For insight into the process of writing these, see my interview with Tania Zamorsky, who also wrote a kids’ version of Dracula, here.)

Anyway, in this edition (part of the Great Illustrated Classics series), the story had reached the point where Dracula first accosts Lucy in Whitby. Her friend Mina finds her sleepwalking in a local cemetery, and brings her home. This leads to the following passage:

“Mina put her shoes on Lucy’s feet. She smeared her own feet with mud so that, in case they met anyone, it would look as if she were wearing shoes.” (p. 67-8)

Now, I had no recollection of that from the original text; it seemed such an odd thing to invent, though, that I checked. And sure enough, there it was:

“When I had her carefully wrapped up I put my shoes on her feet and then began very gently to wake her…As we passed along, the gravel hurt my feet, and Lucy noticed me wince. She stopped and wanted to insist upon my taking my shoes; but I would not. However, when we got to the pathway outside the churchyard, where there was a puddle of water, remaining from the storm, I daubed my feet with mud, using each foot in turn on the other, so that as we went home, no one, in case we should meet any one, should notice my bare feet.” (p. 105 of the McNally/Florescu annotated edition)

Okay, it’s there. But it’s such an odd detail to emphasize that I’m now fascinated by it. Why, out of all the myriad aspects of this passage, did the adapter pick this to emphasize? Because by simply repeating it, it’s robbed of its context. The reason for Mina’s odd interest in footwear appears in the next paragraph:

Okay, it’s there. But it’s such an odd detail to emphasize that I’m now fascinated by it. Why, out of all the myriad aspects of this passage, did the adapter pick this to emphasize? Because by simply repeating it, it’s robbed of its context. The reason for Mina’s odd interest in footwear appears in the next paragraph:

“I was filled with anxiety about Lucy, not only for her health, lest she should suffer from the exposure, but for her reputation in case the story should get wind. When we got in, and had washed our feet, and had said a prayer of thankfulness together, I tucked her into bed. Before falling asleep she asked—even implored—me not to say a word to any one, even her mother, about her sleep-walking adventure. I hesitated at first to promise; but on thinking of the state of her mother’s health, and how the knowledge of such a thing would fret her, and thinking, too, of how such a story might become distorted—nay, infallibly would—in case it should leak out, I thought it wiser to do so.” (p. 105 of the McNally/Florescu annotated edition)

The novel is set in Victorian England, where propriety most definitely did not include young unmarried women wandering about graveyards in the middle of the night clad only in their robes and nightgowns. A robe might pass as a cloak in the darkness, but pale bare feet would be a dead giveaway. It’s a reflection of the novel’s (unconscious? opinions vary) theme of women needing protection at all times, because they simply can’t be trusted with their own agency—a defining aspect of the Victorian world view, and Bram Stoker was nothing if not solidly, stolidly Victorian.

So whenever I read the Whitby scene, which marks Dracula’s arrival in England, I’ll now picture Mina with her mud shoes. It’s just one more bit of weirdness in a novel delightfully full of them.

(Title paraphrased from Elvis Costello, with apologies.)

October 4, 2018

“I am fearless, and therefore powerful”: the Monster and the Siren

We sometimes forget, because familiarity negates it, that Frankenstein’s monster is supposed to be scary.

I’m talking specifically about the Boris Karloff monster from the first three Universal films, Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, and (my favorite) Son of Frankenstein. I suppose the later films with other performers as the monster (Lon Chaney, Glenn Strange, Bela Lugosi, etc.) could also be considered scary, but they bring none of Karloff’s soul pain to the part. They just copy the makeup.

Many years ago, a friend gave me a collectible figure of the monster from Son of Frankenstein, delightfully swinging Lionel Atwill’s wooden arm. And suddenly, my daughter (whose internet nickname is the Siren) is afraid of it. Now, this Frankenstein collectible has been literally on the same shelf for her entire life, but thanks to one of her little friends pointing it out, now she’s afraid of it. I tried to explain to her that it was just, essentially, a toy, but some fears resist rational thought. And you can never, ever dispel them by simply saying, “There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

So that night, as her bedtime story, I told her the tale of Frankenstein from Mary Shelly’s novel.

Because I was telling it from memory, rather than reading it, I could place the emphasis where I wanted. And in this case, I stressed the monster’s loneliness, pointing out that people in the story reacted the same way she did to his appearance, without making any effort to learn about the kind of person he was. I pointed out that Victor, essentially the monster’s father, had failed to teach the creature any of the most basic human skills, or even give him a name. Alone, unloved, untaught, he was forced to find his own way in the world.

And thanks to the recent tragedy in our own family, telling it this way brought me to tears. Since she’s seen me cry a lot in the last few weeks, she immediately hugged me and encouraged, “Think a happy thought, Dad!”

The next day, she came home from school and showed me the Frankenstein picture book that she drew. It’s only three pages, but it tells a whole story. In it, the monster is lonely until he finally finds a friend (a Girl Scout), after which he smiles.

She plans to continue their adventures, and I can’t wait. We also read a children’s version of Frankenstein. And I hope she never forgets the lesson in compassion that’s at the heart of the Frankenstein story.

(quote in the title from the novel Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley.)

July 29, 2018

A Tale of SF/F/H at Its Best, and a Thank You

To read the news (and the blogs, and the social media posts), you’d believe that the science fiction, fantasy and horror community is made of up of crying man babies who freak out at the slightest deviation from what they believe a property, or a person, should be. From remaking The Last Jedi to trolling Leslie Jones, from complaining about colorblind casting to crass (and illegal) treatment of women at events, the genre can seem like a cesspool, not just to outsiders but to some of us within it. Everyone has a story, it seems, about some creator or fan being an asshole.

This is not one of those stories.

Recently my son Charlie passed away. He was only ten, and the pain was, to borrow a phrase from Robert B. Parker, positively Wagnerian. It still is. Many of my wife’s relatives came to town for his funeral service, but since most of my immediate family is either dead or unable to travel, I knew I wouldn’t have as much emotional support, and I was prepared for that.

What I was not prepared for was the way the science fiction, fantasy, and horror community had my back.

I won’t drop names, but I will say that some people made Herculean efforts to be there for the funeral. Seeing their faces, receiving their hugs and tears, just knowing that they cared enough to be there for me, made the worst day of my life bearable.

And that wasn’t all. The outpouring of flowers, gifts, and financial help was overwhelming, and I’ll never be able to fully express my gratitude. Thanks to them, many of the immediate worries have been alleviated and we’ve been able to concentrate on supporting ourselves, and our other two children.

In this situation, the worst thing is feeling alone, and the SF/F/H community—my community—assured me I was not.

The jerks and assholes out there get press far out of proportion to their numbers. And perhaps this story, a tale of good people–writers, readers, fans–doing good things for one of their own, isn’t as juicy. And those stories do need to be told, so we can stop the trolls. But this is an important story, too, because I think it’s a more typical story of fandom and community. This is what we do at our best, and we need to remember, and celebrate, that.

From the Bledsoe family, in memory of our son Charlie, who loved Pacific Rim and Erin Hunter’s Warriors series and Overwatch and would’ve one day been a fan of so much more, we thank you.

A Tale of Fandom at Its Best, and a Thank You

To read the news (and the blogs, and the social media posts), you’d believe that the science fiction, fantasy and horror community is made of up of crying man babies who freak out at the slightest deviation from what they believe a property, or a person, should be. From remaking The Last Jedi to trolling Leslie Jones, from complaining about colorblind casting to crass (and illegal) treatment of women at events, the genre can seem like a cesspool, not just to outsiders but to some of us within it. Everyone has a story, it seems, about some fan being an asshole.

This is not one of those stories.

Recently my son Charlie passed away. He was only ten, and the pain was, to borrow a phrase from Robert B. Parker, positively Wagnerian. It still is. Many of my wife’s relatives came to town for his funeral service, but since most of my immediate family is either dead or unable to travel, I knew I wouldn’t have as much emotional support, and I was prepared for that.

What I was not prepared for was the way the science fiction, fantasy, and horror community had my back.

I won’t drop names, but I will say that some people made Herculean efforts to be there for the funeral. Seeing their faces, receiving their hugs and tears, just knowing that they cared enough to be there for me, made the worst day of my life bearable.

And that wasn’t all. The outpouring of flowers, gifts, and financial help was overwhelming, and I’ll never be able to fully express my gratitude. Thanks to them, many of the immediate worries have been alleviated and we’ve been able to concentrate on supporting ourselves, and our other two children.

In this situation, the worst thing is feeling alone, and the SF/F/H community—my community—assured me I was not.

The jerks and assholes out there get press far out of proportion to their numbers. And perhaps this story, a tale of good people–writers, readers, fans–doing good things for one of their own, isn’t as juicy. And those stories do need to be told, so we can stop the trolls. But this is an important story, too, because I think it’s a more typical story of fandom and community. This is what we do at our best, and we need to remember, and celebrate, that.

From the Bledsoe family, in memory of our son Charlie, who loved Pacific Rim and Erin Hunter’s Warriors series and Overwatch and would’ve one day been a fan of so much more, we thank you.

July 4, 2018

Music, identity, and the teenage heart

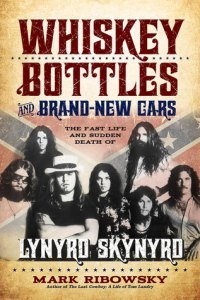

I just finished Whiskey Bottles and Brand-New Cars, a 2017 biography of Lynyrd Skynyrd by Mark Ribowski. I was 14 when the core of the band died in a plane crash on October 20, 1977, the real “day the music died” for my generation. I’m familiar with the broad strokes of the Skynyrd story, and even once saw the Rossington-Collins Band, one of the groups put together by the survivors (I was never lucky enough to see the real Skynyrd, and have no interest in the band currently using that name). I recommend the book to anyone curious about the band, their times, and their impact.

I just finished Whiskey Bottles and Brand-New Cars, a 2017 biography of Lynyrd Skynyrd by Mark Ribowski. I was 14 when the core of the band died in a plane crash on October 20, 1977, the real “day the music died” for my generation. I’m familiar with the broad strokes of the Skynyrd story, and even once saw the Rossington-Collins Band, one of the groups put together by the survivors (I was never lucky enough to see the real Skynyrd, and have no interest in the band currently using that name). I recommend the book to anyone curious about the band, their times, and their impact.

And it prompted me to ask my oldest son, about to turn 14, if he had a favorite song. He said dismissively, “Nah.”

“Do any of your friends have favorite songs?”

“Nah.”

He might have been deflecting; after all, at that age, who’s not self-conscious about their choices? Still, I wondered how common, and how true, that was for his generation. Because when I was his age, music was incredibly important to my sense of identity. You were what you listened to.

Ribowski’s book took me back to the Seventies when I first discovered Skynyrd, and rock music in general. Rock was divided by its own Mason-Dixon line among my friends: you were either into Skynyrd, or Led Zeppelin (also not long for the world; they ended in 1980 when drummer John Bonham died). You either sided with the high-pitched, vaguely effeminate* vocals of Robert Plant, or the growly drawl of Ronnie Van Zant. You either preferred the orchestral shenanigans of Jimmy Page, or the triple-threat guitars of Skynyrd’s Garry Rossington, Steve Gaines, and Ed King. Literary songs about Tolkien and bustles in hedgerows spoke to you, or you thrilled to songs of free birds and three steps towards the door.

Skynyrd’s blistering guitar trio.

Now, you might think a bookish, nerdy kid like me would be in the Zeppelin camp, but not at all. I found (and still find) Zeppelin a self-consciously pretentious and artsy concern, and learning about their blatant theft of other artists’ work (see here) only made me dislike them more. While I confess an affection for Kansas and Styx (I remember thinking the “starship” reveal in “Come Sail Away” was SO COOL), ultimately my loyalties lay elsewhere.

In contrast to Zep, Skynyrd performed songs about people and places I recognized, and sang them proudly with undisguised regional pride (for a deeper analysis of this, check out Dixie Lullaby by Mark Kemp). They, along with Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen, Heart, early Tom Petty and pre-Michael McDonald Doobie Brothers, fought the good fight against the creeping menace of pretentious, snooty bands such as Yes, Pink Floyd, and Jethro Tull (and before you rip me a new one for disrespecting your favorite band, I’m not saying I still think this way; this was my perspective back in the day).

But there were issues with Skynyrd as well. They were also the unmistakable voices of the redneck bullies who tormented me. Just as I couldn’t imagine doing drugs with Zeppelin, neither could I conceive of having a friendly beer with Van Zant and company (and Whiskey Bottles bears that out; no one had a “friendly” beer with those boys). Skynyrd sang both to, and for, cliques to which I’d never belong. It wasn’t until I discovered Springsteen that I found a musical voice for the feelings I could not then articulate.

Which goes a long way in showing music’s importance at the time; it both embodied and reflected its listeners. Our teen years are when we’re most open to music, when we use it to express ourselves either by creating it or sharing it (remember mix tapes?). Popular music functions as a kind of societal glue, a shared experience (“You love that song? Yeah, me, too.”).

At my son’s age, I would have definitely picked “Free Bird” as my favorite, although I wouldn’t now. And don’t get me wrong, I still love it. But also at that age, music was a hugely important part of my life.

So why isn’t it to my son, and his friends?

Either the music has changed, or we have. And either way, at the risk of sounding like an old crank, I worry something crucial and essential has been lost.

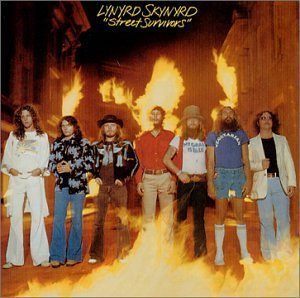

The prophetic “flames cover” of the final album by the real Skynyrd.

*although the girls didn’t think so, that’s for sure.

June 11, 2018

When you make a spectacle of yourself…

My ten-year-old son recently got glasses. It’s not a surprise: my wife and I both wear them. And while two wrongs don’t make a right, apparently two nearsighteds make a farsighted.

I was nine when I got my first glasses. I was in third grade, my first year in the old, long-gone Gibson Elementary School in Tennessee. Now, with the perspective of half a century, I can see it as one of the defining events of my life.

If you’ve been to one of my readings or heard me speak at cons, you might’ve heard me describe Gibson as “a town of 300, 250 of whom were related to me.” That’s a slight exaggeration, of course, but not much. Gibson, as well as the nearest towns of Humboldt and Milan, were filled with relatives. My parents each had many siblings, so my cousins were thick on the ground.

Now, in many stories, Southerners are depicted as helping each other and providing support whenever one of them needs it. That’s true, as long as you’re not too different. It will surprise no one reading this to say I was really different.

And the first person to drive that home was my third-grade teacher, who I’ll call Mrs. M. In my memory, she most resembles Susan Lucci in her Erica Kane prime. I’d never had a teacher who just flat-out disliked me before, and to this day I don’t know exactly why.

And that was when my eyes decided to go bad.

When I told Mrs. M I couldn’t see the chalkboard, she didn’t believe me. She thought I was making excuses for not doing the work (and I always did the work). Finally she moved me closer, ultimately to the front of the row, but it didn’t help. My limit of clear vision is about a foot in front of my face, so even ten feet from the board rendered it blurry. Clearly frustrated by my intransigence, she finally dragged my desk up smack against the chalkboard, to the amusement of the rest of my class.

I was sent to the office, where the principal Mr. Webb sent a note home to my parents. They took me to an eye doctor (who had an enormous rack of John Birch Society pamphlets in his waiting room), and eventually I was presented with a pair of thick, plastic frames and even thicker lenses. On that day my social doom in Gibson was sealed, and remained so until I moved away.

I was sent to the office, where the principal Mr. Webb sent a note home to my parents. They took me to an eye doctor (who had an enormous rack of John Birch Society pamphlets in his waiting room), and eventually I was presented with a pair of thick, plastic frames and even thicker lenses. On that day my social doom in Gibson was sealed, and remained so until I moved away.

Naturally all this came back when my son needed glasses. Luckily, his teachers have all been amazing, even with his occasional outbursts of, as John Hammond said of Ian Malcolm, “excessive personality.”

And even though he also got big plastic frames, it’s a different world now: I haven’t heard the term “four eyes” in anything but old movies and TV shows for years. He seems to like his glasses, even.

Still, every time I see him wearing them, I remember Mrs. M, her black nimbus held in place by a metric ton of hair spray, and the humiliation with which she met my sudden vision problems. I have no idea if she’s still living, and truthfully don’t care. There’s nothing that can undo her damage, even after forty-some years. But the memory does make me appreciate the kindness shown my son, and the changes in society as a whole.

May 14, 2018

Out of the Theater Defeated, Into a Defeated World

SPOILER ALERT for Avengers: Infinity War (and The Empire Strikes Back, if anyone truly needs that now).

Although I’m far too late for this to qualify as any sort of “hot take”–is “tepid take” a thing?– I’ve put a lot of thought into what bugs me (to put it mildly) about Avengers: Infinity War. And just to be clear, I’ve been a huge fan of the MCU, far more than I ever was of Marvel comics (I was a DC guy as a kid). Captain America, a character I found boring and trite in the comics, has become my favorite in the movies; and my inner twelve-year-old still can’t believe that they put millions—millions—of dollars into bringing Thor, my favorite Marvel character, to the screen.

But Infinity War killed all that, just as surely as Superman murdering Zod killed my interest in the DC movies.

This isn’t a critical review. The movie is incredibly well-made: written well, acted with skill and humor, on a huge scale that justifies the nearly three-hour run time. I’m writing here about its effect, particularly the effect of its ending.

The most common response to any dissatisfaction with the ending has been the “Empire” defense, as in, “The Empire Strikes Back ended the same way, and everybody loves it!” Well, no, it didn’t. And here’s why.

At the end of The Empire Strikes Back, our heroes have been routed but not defeated. They’ve learned terrible things, but it didn’t destroy them, and they’re last seen launching their next mission, to rescue Han from Jabba. More crucially, Darth Vader has failed at the very thing that’s motivated him for the whole film: he hasn’t turned Luke to the Dark Side. It’s certainly an open ending, an implied “to be continued,” but it’s also an ending that leaves us, the viewer, with hope.

Leia’s little smile is all about hope.

Infinity War, by comparison, is all about failure.

Every single hero, every single Avenger, fails. Despite multiple chances to stop Thanos, they are unable to do so. We spend two hours and forty minutes watching all our heroes fail, so much so that it retroactively taints the previous movies. How can we enjoy Peter Quill’s charm in the two Guardians of the Galaxy movies, for example, when we now know his immaturity is a big reason for Thanos’s triumph? The hopeful open ending of Thor: Ragnarok is now erased by our knowledge of what that post-credit sequence meant for the Asgardians. And these failures are not just abstract, but painfully personal: Peter Parker’s demise is especially wrenching, and the one I just can’t shake. Our last image is of Thanos, his work done, contentedly watching the sunset just as he said he would.

The movie’s so new I couldn’t find an actual screen shot.

Now, I’m not an idiot. I know this isn’t “The End” for the characters. For one thing, given the immense critical and commercial success of Black Panther, it’s a given than T’Challa isn’t gone for good; same thing with the new, popular take on Spider-Man. I’m sure there’s some elaborate plan to bring them all back and defeat Thanos in the next movie, just as Luke and company rescued Han and defeated the Empire.

But Infinity War doesn’t give us even a hint of that. Instead, it shows us how all our heroes fail. They fail themselves, they fail the universe, they fail us. Cue credits.

And it’s not the time for our heroes to fail. In the real world, failure is all around us: our leaders are hypocrites and liars, many of our male public figures have been shown to be unrepentant sexual predators, people have no sense of security that they’ll have jobs or health care, and minorities are in danger of being killed at any moment. Make no mistake, in the real world, Thanos has already won. The difference is, the half of the population getting destroyed are the poor and nonwhite, not arbitrary ones like in the movie.

And now we’re supposed to pay money to experience those same feelings of hopelessness and despair writ large on a movie screen?

I realize most people don’t have a problem with it. The movie’s already grossed $1 billion and counting. But we also live in a world where empathy is a dying skill. People don’t even feel for the immigrant family living in terror down the road, or the women who dread walking down the street alone. So why should they care about costumed heroes?

I don’t have an answer for that. I just know that the MCU deliberately set out to kill the hope in its universe. Yes, it’s temporary; all comic book deaths are temporary. But in the moment, that doesn’t matter. They send us out of the theater defeated, into a defeated world.

At a time when we needed heroes, they took them from us. And I don’t know if I can forgive that.

If Thanos had used this helicopter in the movie, perhaps I could have forgiven the ending.

April 30, 2018

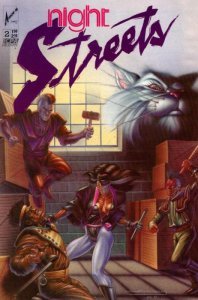

Revisiting Night Streets, Part 3

You can read part 1 of this series here, and part 2 here.

I’m old enough to remember when comics were considered strictly for kids. The very term “comic book” implies the immaturity and humor of the earliest examples. Comic strips in the newspapers were even grouped together on what was called the “funny pages.” The idea that one day comics would be considered literature–that there would be something actually called a graphic novel–would have made my parents’ generation either laugh out loud, or condescendingly shake their heads. But my own kids see comics as just another literary form, totally without any stigma.

Mark Bloodworth, the artist/author of Night Streets, is exactly two days younger than me, so he remembers it, too. A Michigan native, you can read about his career here. I wanted to talk to him about Night Streets, and he was kind enough to answer my belated fanboy questions.

Mark Bloodworth, the artist/author of Night Streets, is exactly two days younger than me, so he remembers it, too. A Michigan native, you can read about his career here. I wanted to talk to him about Night Streets, and he was kind enough to answer my belated fanboy questions.

I know you didn’t create Felonious Katt, but clearly the character spoke to you. What was it about him? And what did you change from the original concept?

Ok, this is going to be long – lot of set-up:

Yes, Katt was created by Rob Knight; he was a friend of Ralph Griffith and Stuart Kerr. He was there with them at the beginning of the Fantastic Fanzine back in the 1980’s along with Randy Zimmerman. So they had the reviews and editorial portion of the Fanzine down but wanted to put in some actual sequential art stories as well. Rob had his character and cast so they started with that; I believe Ralph may have done the art on the initial story before they started looking for artists, but I could be mistaken. I know they were doing stories of The Wheinous Brothers that Stu was scripting and Ralph was rendering, and there may have been some early stories of The Aniverse by Randy.

Anyway, Rob had Katt and wanted an artist for that. Eventually, those guys separately met me, Guy Davis and Vince Locke at local conventions and asked us to contribute. I didn’t have anything raging to get out of me, but Rob approached me about illustrating his story of Katt. I liked it because it reminded me of an episode of The Incredible Hulk where Banner intervenes with an abused child. So I pencilled it and by then Tim Dzon had been brought in so he inked it.

So, jumping ahead: after a few stories with Katt in the Fanzine, Ralph and Stu decided to start publishing comics. We have Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to thank for that. Not that independent comics hadn’t been published before, but Eastman and Laird opened the flood gates to aspiring creators. So we all entered the arena of the black and white independent comics of the ’80’s.

Now, Stu and Ralph had the ideas for The Realm and tapped Guy to pencil, and Deadworld, on which Vince would do all the chores except scripting back then. “So, Mark, what do you want to do?” Well, I thought there’s no way a Felonious Katt book is going to fly, even though Rob gave me total ownership of the character; besides, at this point, Randy along with Sue Van Camp were already doing Tales from the Aniverse (a quasi-serious funny animal book).

I decided I could still use Katt as a “Kingpin” sort of character and just expand the scope to include the entire city. My inspiration came from the TV shows at the time (Hill Street Blues, St. Elsewhere, etc.), and also in the comics at the time, Frank Miller’s run on Daredevil along with Love and Rockets by the Brothers Hernadez. They had already been combing realistic stories with the fantastic for years.

Basically I envisioned an ensemble piece with no definitive “lead” character. That’s when I decided to create Black Dahlia as vigilante character along the lines of The Huntress with the look of Black Canary. I needed Black Dahlia there because if I already have the city and a mob boss – along with other gangs (big and small) I wanted that third entry into any storyline (i.e., two gangs go to war then BD shows up and screws everything up). I also needed that because it would be rare for Katt to come out in public. That’s another thing I changed from his initial outing: he just doesn’t walk down the street thinking to himself.

Is the Black Dahlia strictly a human vigilante, or would she be revealed to have any superpowers?

Is the Black Dahlia strictly a human vigilante, or would she be revealed to have any superpowers?

Yes, strictly human, along the lines of Batman, and The Huntress. She may have gotten some extra powers at some point should things have continued, Arrow Comics-wise. The last book they published was System Seven and that was totally full on superhero stuff. So I may have taken advantage of that and upped her strength and healing and such.

Now, to answer the question that just popped in your head: “Were the books all connected?” Yes and no. It was never the initial intention, but should things have lasted long enough, we did have ideas and plans in place to do a crossover series with all the existing properties. We were thinking of this as early as late ’86 or early ’87. If you check out Night Streets issue #4, page 8, the second headline of the paper Captain Harrison is reading says: “Michigan Millionairess and friends still missing.” That is a direct call-out to the four main characters of The Realm. So their universes are connected.

What would Mal’s Black Dahlia comic book have been like? Would he present her actual adventures, or use fictional ones to build her legend? Did you plan to include it in future stories, the way “The Black Freighter” was used in Watchmen?

Well, first, let’s get this out of the way. The character of Mal Brayton was what we would now refer to as a “Mary Sue”–he was me. I’m sure that was self evident, but I wanted to make sure that was out there.

That being said, yeah, probably there would have been a story that would have dealt with that, or even actually putting out a Black Dahlia comic as if it were written and drawn by Brayton. As to the in-universe stories? Possibly a mixture of real adventures and made up ones, to keep up with the publishing schedule. Looking back, I think the best way to use that leverage would be to create the Black Dahlia comic and release that, then do a story later on that shows a parallel between what “really” happens and what winds up in the book.

A little of both. I would want to continue on with the ’80’s timeline but still do stories that jump ahead and behind. I have a storyline of doing like a Godfather II thing: a storyline from the ’80’s or so, along with showing Mal’s family, Shantel’s, and Katt’s from back in the late ’20’s – early ’30’s during the ending of Prohibition, to show how it employed and affected their families.

A little of both. I would want to continue on with the ’80’s timeline but still do stories that jump ahead and behind. I have a storyline of doing like a Godfather II thing: a storyline from the ’80’s or so, along with showing Mal’s family, Shantel’s, and Katt’s from back in the late ’20’s – early ’30’s during the ending of Prohibition, to show how it employed and affected their families.

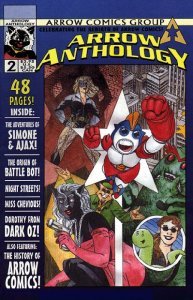

There was a story I did for Arrow Anthology that shows Blossom Colbert as an older woman in 2024, relating a story to a girl regarding something that occurred during the ’90’s.

Looking back, what do you think works the best? And what do you wish you’d done differently?

BEST: I think the ensemble piece of it really works. I wanted to do stand-alone stories of all the characters in some issues knowing that it would all connect at some point. An example would be something like seeing Capt. Harrison on vacation or on a holiday leave with the family, and something triggers a memory about the first time he and Black Dahlia crossed paths. Stuff like that.

DIFFERENTLY: I would have tried to get other creatives involved, art-wise. That way I could take a break from trying to get it all done. That is one of the biggest reasons the book ended. Even after Arrow Comics dissolved, I still had areas to get it published. I was just burnt out.

How often do people mention Night Streets to you at conventions and other fan gatherings?

Oh I get a few – not a lot – but a few. Maybe about fifteen or so during a three day convention. Mostly it’s about Deadworld or any of the later things I did with Caliber. I still get a rare Cheerleaders from Hell comic to sign. I don’t even have one of those anymore.