Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 9

May 20, 2016

Contest Winners!

The results are in! The winners of the advance reader copies of Chapel of Ease are:

Renee Conley

Donna Wilcox

Jennifer Brozeck

Eddie D. Moore

Sylvia Simpson

Cynthia Makowski

Kathy Rudolphe

Amber Barnes

Teresa Gunderson

Steve Krodman

Watch for an e-mail from me very soon!

Thanks to everyone for entering, and there’ll be more giveaways when the final book comes out.

May 16, 2016

Across the same river with The Idylls of the Queen

Alice Walker wrote The Same River Twice about the process of turning her novel The Color Purple into a movie. The title itself is a paraphrase of the philosopher Heraclitus, and is more fully translated as, “You cannot step twice into the same river, for other waters are continually flowing on.”

In 2011, I wrote Dark Jenny, the third in my Eddie LaCrosse series, which put my hero into a very Camelot-like kingdom, where a knight has been poisoned and the queen is blamed. I tried to write about the difficulty in living up to ideals, the dangers of self-delusion, and above all, the need for heroes most especially in worlds that tend to tear them down. I used Arthurian legend as my jumping-off point, most particularly the story of the poisoned apples and the false Guinevere from Le Mort d’Arthur. I changed the names, because I’d already created my own fantasy world in prior books, but I didn’t disguise the source. The source was part of the point.

But as it turns out, I wasn’t the first to use this bit of folklore as a novel’s inspiration. And thanks to an online friend (exactly who I can’t recall; if I do, I’ll update this), I’ve now read the work of someone who crossed this particular river long before I even thought of it.

1982’s The Idylls of the Queen, by Phyllis Ann Karr, starts pretty much as my novel does: with the murder of a young knight by poison. Like my novel, her main character——in her case Sir Kay, Arthur’s foster brother and seneschal——is our first-person narrator, and functions throughout as a sort of detective. But that’s where the similarities end, and I’m delighted to say an entirely different novel unfolds.

Karr is interested mainly in the various feuds, grudges, family secrets and entanglements of the Knights of the Round Table. Everyone, it seems, is someone’s brother, father, nephew or bastard son, and the cavalcade of names is almost as overwhelming as it is in Malory. The novel is mostly conversations, chiefly between Kay and Mordred, the incestuous bastard son of Arthur and his half-sister. There are also ladies: Nimue, the Lady of the Lake; Morgan Le Fay, supposed enemy of Arthur, her half-brother; and Guinevere, whom Kay has secretly loved for decades.

This is, in effect, a cozy locked-room mystery that finally plays out in a very “I suppose you wonder why I’ve asked you all here tonight” final confrontation. Kay is a grumpy, bitter, yet noble point of view character, and his observations keep readers interested even when the parade of similar names (i.e., Gawaine, Gaheris, Ywaine, etc.) threaten to make our eyes cross.

It’s very rare that you get the chance to read an alternate version of your own book. Not only is this Arthurian, it’s a mystery, told in first person, about the same bit of folklore I used to begin my book. It also makes pithy observations about the dichotomy between the knights’ chivalric ideals, and the considerably less noble reality. There are differences, of course; mainly in tone, in the choice to use the actual Arthurian setting instead of a Camelot-like one, and in the identity of the poisoner. But at the same time, it was like walking back through a garden I thought I’d already thoroughly explored, only to find a maze of alternate passageways hidden in the hedges. And, to be fair, Karr did it first.

And she did it very well. Once I started reading, I could barely put down this book to make sure my children were fed. If you’re a fan of Arthuriana, you’ll adore this. And if you enjoyed Dark Jenny, you’ll especially get a kick out of crossing that same river again with The Idylls of the Queen.

Dark Jenny cover

May 12, 2016

The Truth About Writers on TV and in the Movies

Last night on Modern Family, a show I love thanks to the entire cast’s impeccable comic timing, regulars Phil and Cameron met a famous novelist on a passenger train. Said novelist, Simon Hastings (played by Simon Templeton, whose real name sounds like a pen name), is writing a mystery novel about a murder on a train, and of course he’s writing it on a train, on a typewriter, in the pub car. Now, I may not be a best-selling novelist,* but I doubt very seriously whether any novelist could work this way, let alone a successful one. He might ride the train for research, he might even do some writing while there, but that’s about it. The rest is what people imagine novelists do, typewriter and all.

It’s almost impossible to realistically depict a writer’s life, because to an outsider, it’s boring. We sit, mutter to ourselves, type, backspace, retype, and repeat to infinity. Sometimes, but not always, we put on pants. Yet movies and TV insist on showing writers who have exciting lives (think Castle) that, in reality, would barely leave time for writing.

I first noticed this in 1985, when St. Elmo’s Fire came out. I couldn’t stand the movie for a lot of reasons (Rob Lowe wearing more rouge and eyeliner than any of the female cast, Judd Nelson as a total dick who, inexplicably, we were supposed to like), but mainly because of Andrew McCarthy’s turn as a blocked writer who hung around with prostitutes (but never inhaled), until Ally Sheedy let him bang her on top of his coffin/coffee table. Even though I’d hardly written anything myself then (and certainly nothing worthwhile), I sensed that this was utter bullshit.

There’s a scene in Beloved Infidel, a 1959 biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald starring Gregory Peck, in which Fitzgerald, having sent the first part of a novel to a publisher, bounds to the mailbox to see if he’s gotten a response. The music is jaunty and upbeat as he smilingly checks the mail, finds a letter from the publisher, and opens it. Then, as his expression falls, the music turns dark and Wagnerish. It’s the kind of melodramatic moment Hollywood loves, but to a real pro, it would simply never happen. We take rejection in stride, because if we don’t, it will crush us.

There are films that get at least parts of the writer’s life right. One of the best moments is in The Shining, when Jack Torrance explodes at Wendy for breaking his train of thought. He may be a shit about it, but I guarantee you every writer immediately understands his reaction.

Finally, there’s a recent super cut video that supposedly shows the many portrayals of writer’s block from the movies. Putting aside the fact that I don’t believe in writer’s block (writers write; some days it’s hard, some days it’s easy, but we do it. Do plumbers get plumber’s block?), many of the clips show the writers writing something, then either deleting it or ripping it from the typewriter. That’s not writer’s block, that’s process. I’ve done it more than once writing this very piece.

So don’t trust those depictions of writers. It’s not glamorous, it’s not exciting, it’s certainly not sexy. But it is incredibly rewarding, even if most of those rewards happen in your own head, where only you can see them.

*Although when my new book, Chapel of Ease, comes out, you can change that, hint, hint.

May 2, 2016

I’m giving away 10 advance-reader copies of CHAPEL OF EASE

Chapel of Ease, the fourth Tufa novel, won’t officially be out until September. But I have some advance copies to give away right now.

Here’s the official description:

When Matt Johanssen, a young New York actor, auditions for “Chapel of Ease,” an off-Broadway musical, he is instantly charmed by Ray Parrish, the show’s writer and composer. They soon become friends; Matt learns that Ray’s people call themselves the Tufa and that the musical is based on the history of his isolated home town. But there is one question in the show’s script that Ray refuses to answer: what is buried in the ruins of the chapel of ease?

As opening night approaches, strange things begin to happen. A dreadlocked girl follows Ray and spies on him. At the press preview, a strange Tufa woman warns him to stop the show. Then, as the rave reviews arrive, Ray dies in his sleep.

Matt and the cast are distraught, but there’s no question of shutting down: the run quickly sells out. They postpone opening night for a week and Matt volunteers to take Ray’s ashes back to Needsville. He also hopes, while he’s there, to find out more of the real story behind the play and discover the secret that Ray took to his grave.

Matt’s journey into the haunting Appalachian mountains of Cloud County sets him on a dangerous path, where some secrets deserve to stay buried.

So to win one of ten ARCs of Chapel of Ease, tell me about your favorite musical theater bit: a certain song, a specific performance, a great show, anything. Leave that comment here before midnight on Sunday, May 15.

Look forward to reading your choices!

April 13, 2016

Interview: Marco van Belle, director of Arthur and Merlin

Last week, I posted a review of Arthur and Merlin, a movie that really surprised me with how good it was, and how well it worked within its low-budget means. I asked director/co-writer Marco van Belle if he’d answer some questions about it, and he was kind enough to agree.

AB: What inspired you to tackle an Arthurian movie in the first place?

MvB: When the executive producer proposed the idea of making an Arthurian film set in the Dark Ages to me, I was immediately sold. I mean, how often do you get an opportunity to reinvent two characters as iconic as Arthur and Merlin? But what was really great was that this story was going to be based in the period of history when the characters first appeared in stories. Setting it in the Dark Ages wasn’t just a blue-sky idea, it was actually an opportunity to return the characters to their proper timeframe. All the medieval incarnations of Arthur and Merlin that we are so familiar with from books and films were adaptations of the original Celtic myths, but somehow nobody before us had made a film that tapped directly into those original myths.

Kirk Barker as Arthur

You chose to make Arthur and Merlin contemporaries, rather than the traditional elder/student relationship. Why?

You very astutely pointed out in your review of the film that we went with a Butch and Sundance ‘buddy movie’ approach, and this is exactly how we described it when we were developing the script. Given that we were going to be reimagining the characters as Dark Age Celts, I felt it was important to also bring a fresh approach to their relationship. We’ve seen the wise old wizard version of Merlin too many times, and Arthur is often portrayed as an almost infallible ruler well established on the throne. I wanted to do something different. I wanted to peel back the layers of familiarity and get to the nitty gritty of what makes these two men tick. Sometimes it’s easier to do that with characters who are contemporaries and can spar off each other as equals.

The story of Arthur is an epic tale, and often requires epic filmmaking. Low budget films often try to cheat this with bad CGI. You avoided this particular pitfall rather neatly; how hard was it?

It was incredibly hard! But how we did it started with the structure of the script. I decided that the only way to avoid the film looking like so many other low budget fantasy efforts was to ensure that we never attempted any scenes that we couldn’t deliver to a high standard. For example, while we do have a big battle scene in the film, we focus on one warrior’s story within that battle. Also, by keeping the magic restrained and focusing on elemental spells (wind, fire etc.) we avoided the need for CGI monsters and other things we simply couldn’t afford to do justice to. This approach put a huge emphasis on the quality of the writing and the dialogue, and we needed to cast excellent actors to make sure the film was a compelling watch even though it doesn’t even try to reach the kind of levels of CGI and VFX that current Hollywood blockbusters do.

Stefan Butler as Merlin

One thing that really jumped out at me was the vividness of even the smaller parts. The woman who berates Merlin, for example, or the warlord Arthur talks into helping him. In fact, all the performances are really strong. How difficult was it getting them on a low budget and a tight schedule?

I’m so glad that you like that scene. That’s probably the piece of writing that I’m most proud of in the script. And what an actress! She’s called Helen Philips, and she made me cry the first time she read for the role. I love ensemble films, and even though this isn’t quite an ensemble piece I always try to ensure that every character is compelling and has something to say. I hate films that have any ‘filler parts’ that don’t stay with the audience. I’m actually really proud of our entire cast. Kirk Barker and Stefan Butler as Arthur and Merlin carry the whole film and work brilliantly off each other, especially when the comedy comes into their relationship later in the film. And Nigel Cooke as the evil wizard Aberthol is a hugely experienced British theatre actor, and he needed to draw on that to deliver a bad guy who was larger than life without becoming too hammy. The schedule made it difficult for the cast. They usually only got three takes of every shot, and that’s a lot of pressure, especially for Kirk and Stefan who knew they had to nail it as the two leads. But the old rule is true – if you cast well, you’re halfway there. Thankfully we put a lot of effort into finding the best actors for the job.

Has the film gotten the reception you’d hoped for?

When I came onto the project I was told that I had to write and direct a film for hard-core fantasy fans and people who love Arthurian stories. The reaction from that niche audience has been fantastic. Kirk and Stefan have developed quiet a fanbase now, and they’ve even been signing autographs at some of the big European fantasy con events. But what’s also gratifying is how many people outside that niche audience are also enjoying the film. I tried to make sure that the film was going to have both targeted and broad appeal, and I think I succeeded. I had a twitter conversation with a man in America a few weeks ago. He came across the film by chance on Redbox and rented it. He told me that he had to keep it for an extra day so his kids could watch it twice. It’s really nice to have made a film that has that kind of appeal. I think it’s the kind of film I would have wanted to watch twice when I was younger.

Arthur and Merlin is currently available at Wal-Mart and Target in the US, and is showing on Showtime’s Beyond and Family Zone channels.

April 4, 2016

Film Review: Arthur and Merlin, an unexpected treat

Sometimes, if you leave yourself open, you trip over things that speak to you in unexpected ways. A song from an artist you normally can’t stand, a surprisingly wise observation from someone who’s otherwise an idiot, a book by an author you’ve previously (no pun intended) written off. And, if you’re like me, you might stumble on a DVD in a store and buy it on a whim, just because it’s about a topic you like. You don’t expect much, and then you find out it’s terrific.

Arthur and Merlin, a 2015 movie from England, is just such a surprise. It’s an unexpectedly fresh take on the Arthurian story, enlivened by sharp writing, great performances and an approach that mitigates the low budget; you don’t feel cheated of epic battle scenes because the story doesn’t lead you to expect them.

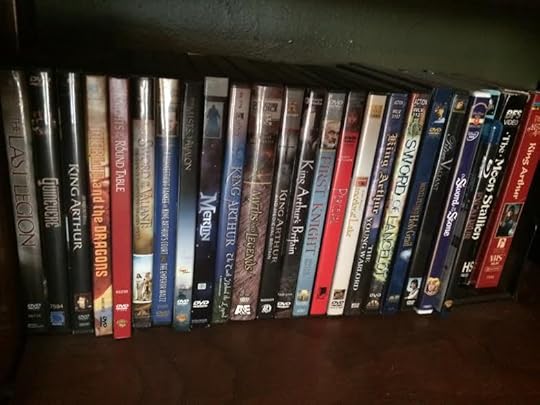

My Arthurian movie shelf. Yes, I even have First Knight and Sword of the Valiant. Both have their interesting points.

Arthur and Merlin begins with the boy Myrrdin watching his mother die at the hand of the evil druid Aberthol (Nigel Cooke, riding the edge between hammy and serious). When Aberthol calls for Myrrdin to be killed as well, young Arthfael saves him. Myrrdin vanishes into a forest haunted by the ancient gods, the Tuatha Dea (not the band). As a hermit there, he learns their magic, and so is ready to help an adult Arthfael when he comes searching.

That’s just the start, and I don’t intend to give a detailed synopsis. What I will tell you is that everything here works. Kirk Barker, as Arthfael/Arthur, is more than just a warrior; he’s also the kind of leader who inspires others to rise above their petty concerns. It’s a side of Arthur that seldom gets depicted, and Barker does great work bringing it to life.

His prickly relationship with Myrrdin/Merlin (Stefan Butler) is also a surprise. In place of the usual mentor relationship, the two are presented as contemporaries; the first person Arthur has to win over to his cause is the hermit wizard, who has no interest in the affairs of men. Once committed, Merlin is still his own man, not a sidekick; this is Butch and Sundance, not Batman and Robin.

The screenplay by director Marco van Belle and Kat Wood gives the actors a lot to work with, even down to the smaller parts. There’s a scene where a childhood friend rightly tears into Merlin for his failure to protect her people. It’s the kind of scene often left out of fantasy movies, a terrific bit of humanizing for Merlin and an insight into the fear he constantly denies. And it’s the sign of filmmakers who understand that when a movie lacks a budget, it can compensate with great writing, strong performances and a sure directorial hand.

I’ve often bemoaned (okay, bitched) about the crappy quality of our own low-budget fantasy movies. We’re apparently satisfied with Sharknado and its ilk, movies that are not just cheaply made, but cheaply thought out. There’s no reason a low-budget movie about sharks in a tornado couldn’t be clever, and funny, and even suspenseful, except that the makers don’t see any need for it. They know we’ll accept junk, so they give us junk. (A notable exception are the films produced by Utah’s Arrowstorm Entertainment, especially their Mythica series. Read more here.)

Arthur and Merlin isn’t junk. It’s a fully-formed movie world, rich with characters and a story that builds itself out of the standard Arthurian tropes in really surprising ways. I love all things Arthurian, and I really loved this movie. It surprised me, and I hope you give it a chance to surprise you, too.

(Arthur and Merlin is currently available at Wal-Mart and Target in the US, and is showing on Showtime’s Beyond and Family Zone channels. I should also mention you can check out my own Arthurian novel, Dark Jenny, one of my Eddie LaCrosse series. Scroll down to find a free preview of the first chapter here.)

March 14, 2016

A Response to the Lesbian Death Trope

I don’t watch A Game of Thrones. Although it may be, as Ian McShane says, merely “tits and dragons,” it’s also a show that prides itself on killing off characters with no warning, no build-up, and no apparent reason. That’s too close to real life for me, as I explained here back in 2012.

I also don’t watch The 100. I hold off on any serial show until the run is over and I see if the long-term fans are happy with the ending. I made this vow after I was burned by The X-Files (and the recent reboot made me even swear off that). The fans of Lost and Battlestar Galactica have made me glad I didn’t fall for the traps (or tropes) those shows laid for their loyal audience.

But I’m aware of The 100 because the show caught fan venom for killing off a particular lesbian character, Lexa. That’s become a go-to trope, dating back to Joss Whedon’s killing off Tara in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (in some circles it’s even called “pulling a Whedon”). LGBT fans were particularly upset, pointing out the long history of lesbian characters dying.

How long? Here’s a handy list. As of this posting, it had 133 entries.

Even though I’m not LGBT, I get this. Sure, straight white male and female characters also die on these shows, but you know what? A lot more of them live. If you’re a straight white male or female, you’re still represented.

Keep in mind, this show airs on the CW network, (as do Arrow, The Flash, The Vampire Diaries and the MILF comedy Significant Mother) and thus a large part of these shows’ audience are teenagers and young adults. Do you remember what it was like as a teenager? Any teenager? Those years are awful, full of self-doubt and misery. Emotions are raw and overpowering, and the conviction things will never get better looms large. Luckily, our society (and the CW) provides plenty of role models in media to show that there is a light at the end of the tunnel. But only if you’re (usually) straight and (most often) white.

Now imagine you’re an LGBT teenager, with all the extra bullying and abuse it all-too-frequently entails, and all the representations of your “kind” in popular media, in the shows you love, are constantly killed off. It would be hard not to see that as yet another confirmation that there’s no future for you.

I don’t advocate censorship. People are free to write what they like, and to make the TV shows they want. The creators of the show were all over the web explaining their reasons and creative processes. Critics, looking at the show as a whole, had a wide spectrum of reactions, for an equally diverse set of reasons.

But it really, I suspect, comes down to that half-assed style of writing so many in Hollywood have mastered: when in doubt, when the ideas aren’t working, kill someone. I sometimes wonder how many of these writers have ever experienced the death of someone close, because they treat it so cavalierly.

And that’s something you’d think they would have learned: if they treat their audience just as cavalierly, they can’t expect that audience not to get pissed off.

Hell, I’m pissed off. And I don’t even watch the damn show. And if you decide that invalidates my opinion, I can’t argue with you.

February 18, 2016

Writing Novels and Novellas in the Same Series

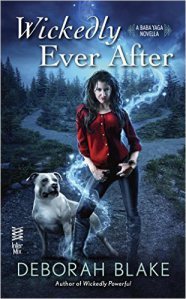

My friend Deborah Blake has just released her latest “Baba Yaga” novel, Wickedly Powerful. Last month, she also released a novella in the same series, Wickedly Ever After. Here she explains the challenge of writing different types of stories in the same series.

And leave a comment for a chance to win a signed book!

Someone asked me in an interview recently what the difference was between writing novellas and novels in the same series, and if one was easier than the other. The answer, of course, is that they are both hard. But that each one has its own challenges and its own rewards.

Someone asked me in an interview recently what the difference was between writing novellas and novels in the same series, and if one was easier than the other. The answer, of course, is that they are both hard. But that each one has its own challenges and its own rewards.

So far in my Baba Yaga series, I have written two novellas and four novels (the third one just came out February second, and the next one will be out in October) and it has been interesting to play with the different forms.

Unlike my pal Alex, I haven’t written very much short fiction. Other than a couple of short stories (including the one published in The Pagan Anthology of Short Fiction, where Alex and I first “met”), I’ve almost exclusively written in the long form. In fact, when Berkley asked me to write a prequel novella for the Baba Yaga series, I’d never written a novella before.

It’s harder than you’d think.

With a novel, the challenge is mostly in coming up with enough story to fill the pages—about 90,000 to 100,000 words worth. You need to build complicated characters and intricate intertwined plotlines and create enough tension to keep people reading chapter after chapter.

With a novel, the challenge is mostly in coming up with enough story to fill the pages—about 90,000 to 100,000 words worth. You need to build complicated characters and intricate intertwined plotlines and create enough tension to keep people reading chapter after chapter.

Of course, in a series, you may have some of the same characters showing up over and over, but since an author can never assume that his or her readers have actually read the previous books in the series, each book also need to recap the necessary information from the other books without using the dreaded “info dump.”

In a novella, on the other hand, you don’t have time to explore either the characters or the plot in such depth, so you need to be able to get across much of the same feeling in a lot fewer words. On the other other hand, it is a lot shorter, so it is way faster to write!

I had two different goals with the two novellas, in part because they fell at different places in the series. The prequel novella, Wickedly Magical, came out before the first novel and was intended to introduce the reader to all three of the Baba Yaga characters who would be featured in the first three books, but most especially to Barbara, the protagonist from Wickedly Dangerous. My hope was that the story would intrigue people enough that they would go on to read the longer novel. (Side note: as far as I can tell, it worked! Yay!)

The second novella, which fell after books one and two, and before three, was more of a fun piece that allowed me to follow up on what happened with Barbara after her main “story” was wrapped up at the end of her book. (She does show up in book three and book four. Very pushy, our Barbara.) It was, in some ways, a gift for my readers, who wanted to know what happened next. Wickedly Ever After is a glimpse into what happened after the fairy tale ending. Did she live happily ever after or didn’t she? The novella got to answer that question.

The second novella, which fell after books one and two, and before three, was more of a fun piece that allowed me to follow up on what happened with Barbara after her main “story” was wrapped up at the end of her book. (She does show up in book three and book four. Very pushy, our Barbara.) It was, in some ways, a gift for my readers, who wanted to know what happened next. Wickedly Ever After is a glimpse into what happened after the fairy tale ending. Did she live happily ever after or didn’t she? The novella got to answer that question.

I wouldn’t say that I prefer writing one form over the other. Each has its plusses and minuses. What I really love is being able to tell the stories of the Baba Yagas (and now, their companions The Riders) and share them with my readers. Hopefully my modern take on the traditional Russian fairy tale witches has pleased my readers, no matter what the length of the story.

So, here’s a question for the folks here: Do you prefer reading novellas or novels? I’m going to be giving away a signed copy of the new Wickedly Powerful novel to one lucky commenter.

January 29, 2016

Thoughts on the X-Files, Doctor Who, and Sherlock

When I heard that Steven Moffat is leaving Doctor Who, my first thought was, “Finally.” Of course, he still gets a whole last season to ruin what was once one of my favorite shows, but much like Scott Walker as governor here in Wisconsin, we can only hope his successor will be able to put things back like they were.

I also, like millions of others, watched the first two episodes of the X-Files reboot. I realized that my problems with Chris Carter’s creation are similar to the ones I had with Moffatt’s Doctor Who.

Namely, the shows are based entirely around tearing down heroes.

Moffat’s Doctor Who, and in many ways his other series Sherlock, feature hyper-intelligent protagonists paired with “normal” folks. The Doctor’s companion(s) and Watson are there to be the audience’s eyes and ears, to essentially stand in for us.

But under Moffat’s tutelage, both the companions and Watson exist primarily to chastise their partners for failures measured (of course) by those companions’ standards. I can’t tell you how many episodes of Doctor Who spent their last five minutes with Amy or Clara telling the Doctor how horribly he’d behaved, or how Sherlock’s main character even refers to himself as a “high-functioning sociopath,” a description Watson fully embraces as he frequently scolds him for his behavior.

Both these characters started off as heroes. Granted neither was typical, and certainly both have suffered defeats, but when it came down to it, they were characters to admire. But for some reason, Moffat doesn’t seem to believe in heroes. He sees them as basically assholes with necessary skills, and makes sure their companions frequently remind them of this.

Watching the new X-Files, I was again reminded of why I grew weary of the show before its first cancellation: Mulder and Scully are inevitably going to fail. Every time they’re about to succeed, to prove that there really is a conspiracy involving aliens and the government, we know the rug will be pulled out. That’s the kind of thing that can make a powerful statement once, as in the films The Parallax View or Winter Kills; but when it’s the go-to plot for show, it becomes a kind of masochism to watch it.

I’ve given up on Doctor Who, at least while Moffat’s in charge. It’s a shame, because I really like Peter Capaldi, and wish he was getting the scripts that David Tennant used to get under Russell T. Davies. I’ll probably watch the X-Files just to keep my geek cred, but I don’t expect much from it. The first two episodes (especially that godawful first one) show that nothing has changed in the fifteen years since it went off the air: we may get some chills, and a few good jokes, but ultimately Mulder and Scully will fail.

Have we just outgrown heroes that win with a clear conscience?

January 15, 2016

Thoughts on Clarion, Privilege and Gaiman

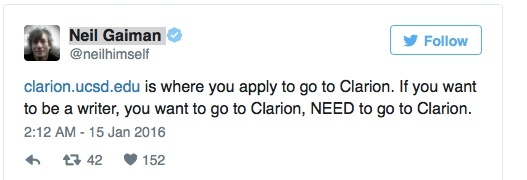

So Neil Gaiman—a writer whose success and public image make him a hero to many aspiring writers—tweeted this:

It got noticed.

Clarion is a workshop for science fiction and fantasy writers, taught by successful established authors in those fields. Its also expensive, long (five to six weeks), and so beyond the reach of a great many aspiring authors. To quote a tweet by author and attendee Kayla Whaley:

Now, I don’t for a moment believe that Gaiman literally meant need, as in you can’t consider yourself a real writer unless you have Clarion on your CV. But at the same time, I understand the outrage of those who see his statement as an unthinking beacon of privilege. Who the hell is Neil Gaiman, who will never again have to worry about paying bills, or child care, or taking time off from work, or any of the day-to-day struggles that most of his readers experience, to tell us what we need? It’s in the same ballpark as Gwyneth Paltrow’s famous statements about her being a “typical” mother.

Like a lot of writers, I never went to Clarion, or any professional writing workshop. I learned to write via journalism, both from studying it and working at it. I like to say it’s one reason my books are so short, but in another very important way, it taught me to approach writing as a job. A reporter is no special snowflake: if he or she can’t do the work, there’s always someone waiting to eagerly step up. So you get on with it, and do the best you can with what you have. That lesson has been incredibly useful as a fiction writer, too.

I did, however, have an interesting chance to observe, from the outside, an MFA creative writing program, thanks to having a girlfriend who was in it. I watched the same group of writers work their way through and all publish their first novels at about the same time. And the biggest thing I noticed was, all those novels were the same. Sure, the backgrounds and styles might be different, but the themes were identical: thinly-disguised autobiography of young misunderstood artists struggling for vindication, dealing with parental issues and, more often than not, finding the kind of love that’s been described as the “manic pixie dream girl (or guy).”

What this taught me was that workshops are a limited kind of help to a writer. A writing teacher can’t really teach you how to write; they can only teach you how they write. Some of their techniques may work for you, some may not. But if you follow their example too closely, you end up writing just like them, and so does everyone else in your class. It’s a lesson I try hard to remember when I teach workshops and classes.

I’ve always held that the best way to learn to write is, simply, to start writing. Writing teachers (whether in schools, writing groups, or workshops like Clarion) can help, to an extent, speed up this process, and certainly the validation is no small thing; having someone you respect tell you they like what you’ve written is a thrill that never gets old. But unless you have it in you to plow through, to learn to spot errors on your own and fix them, you’re probably not cut out for the job.

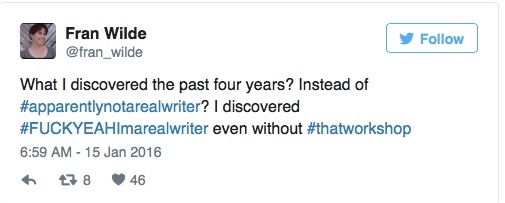

So again, I’m certain Neil Gaiman didn’t mean his tweet to be taken literally. But someone of his stature should understand the power of his words to those struggling up the ladder after him. Or to quote another tweet, from Fran Wilde:

(You can read the rest of Fran’s tweets on the topic here. They’re worth it.)