Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 10

January 7, 2016

Sherlock, by Decree

I’m not a hardcore Sherlockian, but I am a fan. I first came to the great detective through a comic book adaptation of “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” and followed that to the original stories. Since at the time they were still under copyright, I was spared the plethora of half-assed pastiches we’re now awash in; the only non-Doyle story of any note was Nicholas Meyer’s estate-approved The Seven Per Cent Solution.

I’ve watched the BBC Sherlock with the same growing dismay as the recent seasons of Doctor Who, and for the same reason. When Sherlock began, it was clever and quick on its feet, compressing a season’s worth of inventiveness into three episodes. Inevitably, though, it slid into self-referential worship, and the Holmes/Watson relationship became not a friendship but an ongoing scolding, much the way Clara interacted with the Doctor.

The recent Sherlock holiday special, “The Abominable Bride,” was particularly egregious. At first it seemed to be a jaunt, with the cast transported to the 1880s of Doyle’s stories. About an hour in, though, it all became needlessly meta. The cleverness of the early episodes was now replaced with navel-gazing.

To get rid of the sour taste, I rewatched probably my favorite Holmes movie, Murder by Decree. In this Holmes-meets-Jack-the-Ripper tale, Christopher Plummer plays the warmest Holmes ever, and is perfectly complemented by James Mason’s irascible, ever-proper Watson. And most importantly, they convey a genuine friendship, something Sherlock has never really done.

Plummer takes Holmes’ impatience with those less intelligent and skews it from annoyance to amusement. In doing so, he loses the edge of contempt that is the core of Benedict Cumberbatch’s performance. This is a Holmes who actually empathizes with the victims of crime, not one who sees them as mere pieces in a mental puzzle. And Watson is equally as sure of his place in the world; in an early scene, he rallies an opera crowd when a group of anarchists begin shouting abuse at the royal box.

But what sells the friendship is the way they make each other laugh. In their first scene, Watson refers to Holmes as “the prince of detectives,” and when Holmes inquires who might be king, Watson deadpans, “Lestrade, of course,” which breaks them both up…well, breaks them up in a proper British fashion. They laugh together many times in the film, in fact

The BBC’s Sherlock will probably continue for several more seasons, but like Doctor Who, it’s lost its charm for me. Holmes, like the Doctor, should be fun and exciting, not grim, depressing and cold. Murder by Decree gives us a Holmes who’s intellect is matched by his compassion, and I’ll take that over a high-functioning sociopath any day.

October 19, 2015

Guest blog: Mehitobel Wilson on the Blue Alice

Way back in the last century, when the Internet was still shiny, Mehitobel Wilson became one of my earliest online friends. She’s a great writer (the first story of hers that I read began, “Someone was fucking with the pigeons.”), and she’s just finished a new novella, Last Night at the Blue Alice. I asked her to write a little bit about her process, and she’s revealing a previously secret part of it for the first time. I was gobsmacked, and I bet you will be, too.

***

Alex and I have known each other (online) for aeons, close to twenty years now. We’ve always had very different ways of doing things. For instance, he writes a lot of books and works relatively quickly. I do neither of these things. He writes novels. I’m here to tell you about some of the process that helped me write my first long-form story, which is a 30k-word novella.

When a reader asked Alex if he makes a physical map to help him write a complex scene, he said that, for his own process, he usually considers such things cheating.

I built a 1:12 scale model of my novella’s setting.

All of the action in Last Night at the Blue Alice takes place inside one house. Mollie Chandler must undergo the final test that will determine whether she may join an Order that employs time travelers. If she succeeds, she will be the Order’s first Psychopomp.

The Blue Alice is a house famously acrawl with ghosts. Mollie’s task is to travel back in time and alter the circumstances that caused each haunting. She may use any means she likes: she’s studied anthropology and psychology, comparative temporal theory, and, of course, history, but there’s never been a Psychopomp before. No method she chooses will be wrong, as long as it works, and works fast. Mollie only has one night to clear the Blue Alice. Failure ensures one of two outcomes: the Order will cast her into the past to die, if she’s lucky, or exile her outside of time, if she’s not.

The story isn’t about the Blue Alice, and though I love reading books in which the setting feels like a character itself, this isn’t one of them. The Blue Alice is just the structure that has housed many tenants since it was built in 1895, tenants who had the dreams, troubles, joys, and anxieties familiar to us all.

I’ve never tried writing a long piece before. The very notion intimidated me; I’d spent my whole writing career telling myself that my brain just didn’t work long.

My own anxieties were derailing my attempts to dream at the keyboard. I wasn’t blocked per se, but was too easily distracted by the obstacles I’d built.

So I decided to build something else, instead.

I really loved Lauren Bueke’s “murder wall,” and thought I might do something like that. Then I saw Jenny Crusie’s collage process and was completely blown away. Tactile immersion has always been helpful to me, and these approaches appealed to me a lot.

Round about then, my fella and I celebrated our wooden anniversary. He wanted to get me a cuckoo clock, but it turns out they’re really expensive. I opted for a dollhouse kit instead. “Research,” I said. “It’s work. And it’s wood.”

It was wood, all right. It was a box of die-cut sheets. Every piece had to be detached, sanded, painted, teased into sub-assemblies, glued, papered, taped, and sworn at.

While my hands smoothed 178 little wooden giblets that would eventually become decorative gingerbread, my mind relaxed into getting to know my characters. As I snipped the rounded ends off four hundred craft sticks to lay miniature hardwood floors, I listened in on Mollie’s inner monologue. She was determined to pass her test, excited to travel in time, and saddened at the understanding that her success would effectively end any relationships and life goals she’d had before.

As the miniature Blue Alice grew larger and more stable on my work table, the setting and inhabitants solidified in my head. I saw them through my giant’s eyes as I peered through the windows and fiddled with the wiring. I knew what year the wallpaper had been hung in the attic, and how long it had been there, and whose feet had trod the whitewashed boards.

One day, I sat down to fool with the house and couldn’t see it past my own imagination. I was, at long last, dreaming too hard to do anything but write. I left the house unfinished and wrote the book.

It turns out that my brain can indeed write longer stories, and really loves doing it.

Knowing the setting so intimately did help a lot with the narrative itself, by the way. I suck at spatial awareness and am just a catastrophe when asked to follow directions. I’ve gotten lost on a straight road that I lived on for ten years. But I’d been inside the Blue Alice, in a fashion, and knew how my characters would navigate it. There was no need to waste my time figuring out if a door would open inward or outward, or waste the reader’s time with too much description of place, as can happen when a writer is learning the space through their own text. I knew how the moonlight coming through the glass in the front door would fall just short of the doorway to Apartment One. I knew about the long-disused fireplace on the second floor. These sorts of details mattered to the characters who lived with them, and they informed the story.

When I was done with the book, I finished the house. Well, there’s still stuff to do, of course; there’s always stuff to do. I’m fine with that. The house is just telling me that I’m not finished with the Blue Alice.

October 12, 2015

Inspiration and “Copperhead Road”

When I teach writing classes, I often play the song “Copperhead Road,” by Steve Earle. If you don’t know it, here’s the video.

When it’s over, I point out what makes the song so extraordinary. It tells the story of three generations of men named Conlee Pedimore; grandfather was a moonshiner, father was a bootlegger, and the narrator is a pot farmer. The music progresses from pure folk, to slightly harder-edged roots music, to full-blown rock and roll, depicting the progression of generations. The lyrics are filled with specific imagery:

“…he’d buy a hundred pounds of yeast and some copper line…”

“…him and my uncle tore that engine down/I still remember that rumblin’ sound…”

“…now the DEA’s got a chopper in the air/I wake up screaming like I’m back over there…”

When the song over, I usually get a lot of blank stares; what does this have to do with writing?

Then I point out that Earle has told a story of three generations, of three distinct eras, and shown how they intertwine. To do the same thing in prose would take hundreds of pages and probably several years of research and writing; look at “The Godfather,” novel and film(s). Earle manages it in around five minutes.

And THAT is the magic of music.

In the context of the classes, I usually use it to point out how the right detail can do the work of hundreds, if not thousands, of words. But in the larger sense, to me it is magic. I can understand crafting lyrics, chipping away until you’ve got that diamond-hard bit of perfection.

But the music…I’ll never get that.

I’ll never understand how a simple chord change, how moving your fingers on a fret board can change emotions from anger to joy, from amusement to sadness, from any of our millions of feelings to another of those millions. Yet it happens all the time.

I’ve written many novels, and in most of them music plays a part. But in the Tufa novels (The Hum and the Shiver, Wisp of a Thing, Long Black Curl, and the upcoming Chapel of Ease), music becomes part of the story. The Tufa, descendants of Celtic fae folk now living in Appalachia, keep their magic in their songs. When they play music, or sing certain songs at certain times, unnatural things can happen. As I say, in the story it’s magic, but it’s only a slightly exaggerated version of how I feel about music in the real world.

A national anthem, a school song, a shared memory of that stupid one-hit wonder when you were in high school, all these can pull us together. A protest song can swell the ranks of us-vs-them. A love song…well, we all know what they can do.

What songs have affected you the most, and why/how? And writers: what songs have inspired you?

October 5, 2015

Guest Post: Nicole Winters on Writing for Teens

My friend Nicole Winters has a new novel, The Jock and the Fat Chick, coming out on October 13. She’s been kind enough to talk about the challenge of writing for contemporary teens in their rapidly-updating world.

***

Writing for teens in an ever-changing environment; It’s not as scary as you may think

You know that saying, “The more things change, the more they stay the same”? I find this true when thinking about and writing for the teen audience.

We can all agree that the environment we grew up in as kids is vastly different compared to today, especially with the advent of new technology and the information super highway. Kids can also be under an extra set of self-imposed pressures, like thinking they’ll grow up to be famous, or they must make millions on their YouTube channel, or feeling like they have to resemble their favorite celebrity.

But this doesn’t mean that your approach to writing for this target audience has to become more complicated just because things were much ‘simpler’ when you were their age; it doesn’t. Even though modern kids might be texting, tagging or snapchatting in truncated language, or faced with the pressure to succeed bigger, better and faster, a young character’s hero’s journey will remain the same.

Your teen hero will always reside in that unique place between dependence and independence, community and self, and connection and disconnection. It doesn’t matter if they’re a farmhand from the 50s or wired into technology 24-7, their struggles are universal. Being that age is an intense time, emotions are raw and malleable based on never-ending new information and experiences. They’re constantly exploring relationships between self, peers, family and the larger community. Couple that with the fact that one moment they’re treated like a child and the next expected to think and act like an adult and poor decision making is bound to happen. (Plus, it’s the author’s job to throw the hero head first into problems that are too big for him/her to handle.)

Compare Ponyboy from The Outsiders with Ender from Ender’s Game or Hazel from The Fault in Our Stars: three completely different characters in vastly contrasting environments, right? What all these authors have done successfully is create an intimate world between reader and hero that is intense and emotionally scary. All three heroes are thrown into situations so big that at times not even they know how to process what they’re thinking or feeling, let alone be able to express what they want or even make good decisions. Your teen reader is going to relate to this. Young people don’t want to make mistakes anymore than we do as adults. In a way, reading fiction allows teens to live vicariously through the hero who must face the consequences of certain decisions. Ponyboy, Ender and Hazel are trying to find out who they are and are constantly reassessing relationships with self, peers, family and the larger world.

In my romance novel, The Jock and the Fat Chick, my hero Kevin, is a nice guy, but he is so oppressed by what his buddies consider acceptable when it comes to dating, that I force him into a situation where he makes fun of the kind of girl he’d love to go out with. Falling in love is new to him and knowing that Claire is unacceptable to his peers suddenly places his world on shaky ground. If Kevin were an adult with a wealth of experience, I’m sure the novel would go something like this: Shut your face, this is the type of girl I like, I don’t care what you think. The End. But it’s not. He resides in the area of new experiences and decisions and his mistakes will also be new. He’s fresh in the adult world and trying to control of his own destiny. Who will he be, the guy who caves, the guy who hides, or the guy who confronts? He has no prior experience to draw from and for sure he’s going to cope in all the wrong ways and end up making his life more complicated than it needs to be, but that’s his journey.

Life for teens may have changed since we went to high school, but the challenges of being a teenager remain the same. They’re still people who experience feelings of love, loss, joy and disappointment as they constantly try to navigate through a complicated world.

***

Nicole Winters was told that C-average, learning-disabled students couldn’t possibly grow up to be writers. Nicole proved them wrong. She has an English B.A. from the University of Toronto, loves cats, books, horror films, globe hopping and home-baked cookies. She has once been spotted wearing a sundress. Her previous book is TT: Full Throttle.

September 28, 2015

Review: Epitaph, a novel of the OK Corral

I loved, unreservedly, Mary Doria Russell’s 2012 novel Doc, about the life of Doc Holliday before the infamous events of the OK Corral in Tombstone, AZ. I was just familiar enough with both the history and mythology of the story to really appreciate the way she wove them together. When I saw she’d written a follow-up, Epitaph—subtitled A Novel of the OK Corral—I was both excited and concerned. Doc was perfect; any follow-up couldn’t possibly be as resonant and affecting, right?

I loved, unreservedly, Mary Doria Russell’s 2012 novel Doc, about the life of Doc Holliday before the infamous events of the OK Corral in Tombstone, AZ. I was just familiar enough with both the history and mythology of the story to really appreciate the way she wove them together. When I saw she’d written a follow-up, Epitaph—subtitled A Novel of the OK Corral—I was both excited and concerned. Doc was perfect; any follow-up couldn’t possibly be as resonant and affecting, right?

Well, the short version is that lightning did strike twice. Epitaph is every bit as good as Doc, but whereas the former was a character study, this is an epic. Yet while it does operate on a huge scale, it never forgets that it’s mainly about people, and Russell repeats the crucial thing she did in Doc: she explains how the characters’ thoughts and personalities are the real cause for the events of history and legend.

The book begins with a fourth-wall breaking section that asks us to consider that the so-called “Gunfight at the OK Corral” took only thirty seconds. Those thirty seconds would define the characters for the rest of their lives, whether they wanted it or not. Then we meet Josie “Sadie” Marcus, seen through the eyes of Doc Holliday. Josie becomes our go-to character throughout the story, even though Russell gives us plenty of insights into Doc, Wyatt Earp, and all the other figures. Among her most interesting bits of characterization (and there are a lot) are those that explain how head trauma affects decision-making, and through that, drawing parallels between Wyatt and the traditional villain of the story, Ike Clanton.

Further, there’s another fourth-wall section toward the end that’s absolutely touching in its intent, because there’s no way the reader can follow its suggestion. And the final pages follow the Earp story into years I’ve seldom seen mentioned, let alone dramatized. Because Wyatt Earp lived to be 80, dying in 1929, and that’s a long time to have thirty seconds define you.

The book’s strongest element, though, is its sheer readability. It’s a page turner, written in an open, clean style that never gets in its own way. As a writer, I both envy that and aspire to it, but ultimately can never know if I achieve it (I haven’t asked her, but I bet Russell worries about that herself, too. Only a reader can say if a writer accomplishes his or her goals).

It’s not necessary to read Doc prior to Epitaph. The latter stands quite handily on its own, and only obliquely refers back to the earlier book. And as I said, Epitaph is a different kind of book, bigger and broader, a symphony as opposed to a chamber piece. So whether you’ve read Doc or not, you should definitely read Epitaph, because it puts flesh, muscle, blood and tears on the skeleton we all know as the Gunfight at the OK Corral.

September 15, 2015

A Couple of More Questions on Writing

Here are some more questions from readers, with the same caveat at last week: my answers describe my process, which may be totally different from yours. Neither is “right”; what matters is what works for you.

From Donald Kirby: When you have two openings that appeal equally, how do you choose?

That actually happened to me on Long Black Curl. I wanted to use one of my favorite gambits, one that’s very appropriate to the folkloric nature of the Tufa novels: the storytelling opening. It begins at some point in the future, when a character says essentially, “Let me tell you about something that happened a long time ago.” Then you go into the story proper.

The most famous example is probably the bracketing story of The Princess Bride. It’s present somewhat in the novel, but it’s a more general “why I wrote this” introduction. In the film, it’s literally a story: a grandfather reading to his sick grandson. And we go back to them periodically, providing a meta-context for what we’re watching. The grandson at first takes the piss out of this overly earnest story of “twue wove,” voicing the audience’s doubts; but as he’s drawn in, so are we.

The simplest example in popular culture is probably, “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.” Although it may be hard to remember a time BSW (before Star Wars), it did exist, and without this simple disclaimer, those 1977 audiences would have been totally lost. Where was Earth in relation to Tattooine? Which political party gave rise to the Galactic Empire? Did the spaceships use technology based on nuclear weaponry? With that simple statement, though, the story was separated from any historical context: we weren’t watching typical “futuristic” SF such as Logan’s Run or 2001: A Space Odyssey. We were getting a storybook tale.

For Long Black Curl, I abandoned this kind of opening for a very practical reason: it ruined the suspense for a particular character’s fate. By having this character tell the story, you immediately knew that s/he (nope, not spoiling) survived the events of the main story, and I finally decided the tension of that plot point was more important than showing off my ostensible cleverness with this opening.

In my experience, though, the right opening will suggest itself as you work on the story. I never stop writing the first draft just because it has a bad beginning.

From Jacki Smith: Do you make a physical map of a complicated scene while you are writing?

Simple answer is: no. Although I have done something like that once.

In the Eddie LaCrosse novel He Drank, and Saw the Spider, I found myself writing a banquet scene that included eighteen named characters who had so far appeared in the story. Eighteen. That’s a lot of people to keep up with in any situation, and to do it, I made a crude seating chart. But the main issue was making sure that each character had his/her moment to justify his/her presence in the scene.

For the most part, I figure if I can’t keep it straight in my head, then the reader won’t be able to, either. So using too many crutches is, for my process, cheating. Unless it’s a banquet scene.

Thanks to Jacki and Donald for their questions.

September 7, 2015

A Couple of Questions on Writing

Recently I put out a call for questions to be answered on this blog. Here are a couple of the responses. Keep in mind, though, that these are my processes; your mileage may vary. In the end, all that matters is what ends up on the page.

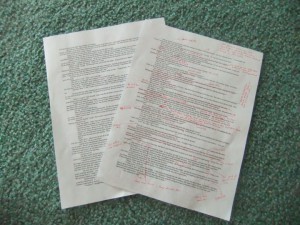

From Tamlyn Garrison: [How do you know] when to stop editing? I’m a chronic over-editor. Or I get multiple critiques and can’t reconcile their varying opinions of problems.

First, two quotes:

“Art is never finished, only abandoned.”—Leonardo DaVinci

“Art thrives on restriction.”—Nicholas Meyer

If I was a cross-stitcher (or knew someone who was), I would already have framed banners over my desk proclaiming these two quotes. Between them, they encompass my approach to revision.

The ultimate goal for a writer should be: This is the best I can do with what I have to work with in the time I have to do it. I learned about deadlines while working as a reporter; when you’ve raced a midnight deadline for a story that has to be in the next day’s paper, a nine-month deadline for finishing a novel isn’t scary at all. But the deadline serves a very important function in the creative process, because it gives you a finite end. I always try to build into my work schedule time to finish a draft and then put it away for a time before returning to revise it. I do most of my revision by hand, in red ink on printouts. This gives me a visual representation of how the revision is progressing, from pages marked with tons of red to, eventually, only a few (or rarely, no) corrections. When I find myself merely adding or moving punctuation, then I know I’ve reached the point where it’s time to stop again, at least for a while.

As for critiques, you have to consider the source. Critics are usually right about what doesn’t work, and usually wrong about how you need to fix it. In my experience, a valid criticism will make you go, “Of course! Why didn’t I see that?” And that’s usually followed by a very clear idea of how to correct it. Invalid criticism will often hurt your feelings and make you feel terrible about yourself and your work, but give you no actual help at improving it. So you have to learn to discern what’s truly useful for you, and let the rest slide.

From Bill Bodden: Do you prefer writing short fiction or novels? Why?

For me, the two forms are a lot like tennis and racquetball: they superficially look similar, but once you start trying to play them, you realize that a lot of the reflexes you develop for one don’t work at all for the other.

Short stories ideally start from the broad base of the tale and narrow to the single point of the story, much like an inverted triangle. Edgar Allen Poe, who essentially invented the modern short story, stressed that one should strive toward a single “effect”: terror, or amusement, or romance, or so on. That single point/effect is ultimately what gives the short story its power.

Longer forms, especially the novel, are usually the opposite. They tend to start with a single point and then spread out to encompass multiple narratives, characters, and themes. It may take a while after finishing a novel for the reader to figure out what s/he really feels about it. And in some cases, such as the works of the late David Foster Wallace, there may be no actual effect: the point may be simply the process of reading itself.

Every word must count in a short story. The writing, and revising, must be ruthless. In a novel, you can pause for a beautifully crafted passage that ultimately contributes nothing to the story’s forward motion, but instead spreads laterally to create part of the overall atmosphere. That sort of luxury is death to a short story.

And I don’t really have a preference. Usually when the idea strikes, I know pretty soon whether it’s the germ of a short story or a novel. Some ideas simply don’t have the depth in them to expand into a novel, whereas other ideas could never work in the hyper-tight form of the short story.

I hope these comments have been useful, or at least entertaining. Feel free to ask any follow-ups in the comments below. Thanks to Bill and Tamlyn for their questions.

July 20, 2015

The Nature of Magic vs Science

Recently best-selling author Dave Farland wrote this article about the cost of magic. It’s an argument I’ve encountered before, and the short version is, everything must have a cost. If you cast a spell, the energy has to come from somewhere. It’s the basic Law of the Conservation of Energy, one of the rules that keeps the universe ticking along.

In other words, it’s science. Not magic.

Leigh Brackett wrote in 1942, “Witchcraft to the ignorant … simple science to the learned,” which famously inspired the third of Arthur C. Clarke’s Three Laws: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” But I’m not sure that’s true anymore. We seem to have achieved a basic understanding of how the universe works, and even when we don’t comprehend particular aspects of it, we don’t automatically assume it’s magical.* We just accept that, at this point in our development, we lack the information to fully understand it.

So I don’t buy the insistence that magic have a cost.

To me, if your magic system has codified rules that explain how and why everything works–if there’s a book, or a tool, or a list, or anything like that–it’s not magic. It’s science, just against a different background. Magic should be something that operates by inexplicable rules, in which cause and effect are only tangentially related: in short, something beyond science, and scientific understanding. I mean, why can’t magic make the magician stronger instead of weaker? Why, instead of a debit, can’t it be a credit?

One of the most horrifying magical events I’ve ever read was in the opening chapter of Seanan McGuire’s first October Day novel, Rosemary and Rue. The protagonist is turned into a koi goldfish, and remains that way for fourteen years. McGuire is such a good writer that she establishes October’s life with her husband and baby girl so quickly and vividly that you feel the awful loss with an intensity that’s actually kept me from finishing the book (I have issues about parents being separated from kids). There’s no discussion of cost to anyone except October, and the magic is powerful and essentially arbitrary (the villain just happens to be next to a koi pond). To this day, I can’t see a goldfish without thinking of that scene, so to me, that is real magic. (The depiction of magic may turn out differently later in the book, but like I said, I may never know.)

The most well-known SF/F depiction of magic is, of course, The Force. In the original 1977 film it was suitably mysterious and yes, magical, but by the time Lucas got done with it, it was simply the byproduct of microscopic organisms, no more magical than bioluminescence. Or poop. And there’s nothing more science-y than that.

When I write about magic, I try very hard to capture the fearful arbitrariness of it. In my Tufa novels, the magic that’s expressed in their music is never clear: songs have effects, but often it’s not the effect the character wants, or it manifests in a way they didn’t expect. The Tufa’s deities, the Night Winds, seldom make their wishes known in plain terms; they offer signs, and portents, and occasionally take a direct hand, but their motives and methods remain as mysterious as their identities. That, to me, is magic.

When I write about magic, I try very hard to capture the fearful arbitrariness of it. In my Tufa novels, the magic that’s expressed in their music is never clear: songs have effects, but often it’s not the effect the character wants, or it manifests in a way they didn’t expect. The Tufa’s deities, the Night Winds, seldom make their wishes known in plain terms; they offer signs, and portents, and occasionally take a direct hand, but their motives and methods remain as mysterious as their identities. That, to me, is magic.

On the other end of things are my Firefly Witch stories, about a modern Pagan priestess. The depiction of magic here is slightly exaggerated for effect, but ultimately based on real Pagan beliefs and practices. One of those is the idea that you never have to use your own energy to work magic; the earth, in the cosmic sense, has an unlimited supply, and a good witch knows how to tap into that.

Now, to be fair, Dave Farland has legitimately written a book called Million Dollar Outlines, which I could not do; my best would be Thousand Dollar Outlines. So his advice is not wrong, nor bad for your career. If his take on magic appeals to you, by all means, pursue it. But for those like me who find that approach too concrete and tangible, think about the things in your life that you consider magical, and then try to figure out why. I suspect that in most cases, the answer will be something along the lines of: “Because it’s inexplicable.”

Science always has an explanation. Magic never does.

—–

*I’m not speaking for or against religion here. Religion is indistinguishable from magic, but that’s a whole separate topic.

July 16, 2015

Book Review: How To Be a Heroine

I don’t write a lot of in-depth book reviews these days. Part of it is practical: with three kids home for the summer, a novel due by the end of the year, and assorted smaller projects, there just isn’t time. I do always give a star rating on Goodreads; Amazon is a non-starter these days, given their arcane rules for who can review what.

The other part is that often, I simply don’t have anything interesting to say. You can love a book to death, and not be able to muster anything that isn’t trite or obvious. And if you do love a book, it deserves better than that.

That said, I recently read How to be a Heroine or, What I’ve Learned from Reading Too Much, by Samantha Ellis, and I couldn’t wait to review it.

I bought this book on one of those whims that strikes sometimes, when you see a book that ordinarily would be far outside your interests but for some reason just immediately grabs you. It serendipitously matched up with two ongoing conversations I’ve been having, one about the word “heroine,” one about what stories I plan to share with my daughter as she grows up.

What I never expected was how eminently, enjoyably readable the thing would be. How readable? I bought it on Sunday, and finished it by Tuesday night. And that’s with the kids all home, and my wife away on a business trip. I found myself reading at every spare moment.

Ellis is a British playwright from an Iranian Jewish family, and growing up she used a succession of literary heroines as templates for her life. Prompted by a visit to the house that inspired Wuthering Heights, she re-examines these characters as an adult, and finds surprises both pleasant and unpleasant.

And funny. Ellis’s voice is wryly observational, and so the humor–never overt jokes–rises naturally from whatever she’s discussing. If you’re going to accompany a writer on a cruise through a dozen novels in search of what they can tell her about herself, it really helps to have an amusing tour guide.

A lot of the characters she discusses I’d never thought about, or certainly not in any depth (for example, I’ve never read Valley of the Dolls). She pegs some things I’d always thought, specifically about Jo March from Little Women and Flora Poste from Cold Comfort Farm. But she also introduced me to novels I’d never heard of but intend to track down, especially Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfield (and its sort-of predecessor, The Whitcharts). And she made me want to re-read Jane Eyre, something I would’ve previously bet would never happen.

As a writer, I probably approach this sort of book differently than a more casual reader. I’ve given a lot of thought to the nature of heroes and heroines. In fact, when I teach my teen writing classes I tell them I don’t like the word “heroine”: a character is either the hero of the story, or they’re not. Gender is irrelevant. And all the characters mentioned by Ellis are definitely the heroes of their stories (although she makes the case for alternate readings in several instances).

I asked Ellis her thoughts on the issue, and she said, “I have mixed feelings about the words ‘heroine’ and ‘hero.’ I know some people say ‘hero’ for both but my feeling is that when we hear ‘hero’ we still think it’s a man. And so, I think, for now, I prefer to specify the gender. However, I am not consistent in this, as I would generally say ‘actor’ rather than ‘actress’…it’s a confusing area! I met someone who says ‘shero,’ which I don’t think is quite right either.”

I asked Ellis her thoughts on the issue, and she said, “I have mixed feelings about the words ‘heroine’ and ‘hero.’ I know some people say ‘hero’ for both but my feeling is that when we hear ‘hero’ we still think it’s a man. And so, I think, for now, I prefer to specify the gender. However, I am not consistent in this, as I would generally say ‘actor’ rather than ‘actress’…it’s a confusing area! I met someone who says ‘shero,’ which I don’t think is quite right either.”

I couldn’t help wondering, as I read How to be a Heroine, what readers thought about some of my “heroines.” Did Bronwyn Hyatt of The Hum and the Shiver inspire people? At least one reader told me that The Firefly Witch’s Tanna Tully touched her because she was a blind character not defined by her blindness. But what makes a female hero connect with readers the way these did with Ellis? Is it something that’s just truly out of the writer’s hands, a unique and individual thing that can’t be planned or done deliberately?

The book doesn’t answer those questions. But it has made me re-think what makes a hero (again, of either gender), and taken me on a grand literary tour. So I highly, highly recommend How to be a Heroine.

July 6, 2015

Guest post: Logan Masterson on the Facets of Death

Logan Masterson (that’s not him above) is, like me, a Tennessee writer of speculative fiction. Below he talks about death in fiction, how it affects us, and why it’s important.

Facets of Death

No, not faces, facets. In fiction. Fictional facets of the very real human experience. Let’s get into that.

The Tufa, they have an eye on death, and means something different to them than it does to us. In my own high-fantasy world of Ordrass, and a million glistening fantasy realms besides, death is a mere passage into higher forms, or a challenge to be forestalled or overcome. Grimmer worlds make something more serious and common of life’s end.

Death is common, of course. It’s all around us, all the time, just a little less prevalent than life. It’s one of the universal experiences, regardless of race, gender, species. In fact, it’s so very difficult for us to imagine a world without it that we demonize immortals in our fiction. Vampires, mummies, armies of animated undead stalking the myriad worlds like moon shadows, these are our visions of death denied. Angels, heavenly beings, are not monsters perhaps, but aliens, unlike us in the extreme.

To watch our favorite characters die sets us to considering the meaning of death. Fiction helps us to examine the end, to turn it in our hands like a bauble. Reflecting life in symbols is something stories do as well as any medium, perhaps better as the experience is longer than a painting, more sustained than a song. The symbols we see in the villain’s final breath, the supporting character’s early demise, or the hero finally laid to rest are powerful. Ubiquitous, too, but still moving.

There are ways to make death meaningless, the best of which are artful indeed. The worst examples seem somehow cheap, at least to me. When death is treated with little impact, a story begins to feel like a backlot set instead of an immersible world.

In a world of doubters and experts, we’ve become inured to death in so many ways. Media (especially movies and TV) can trivialize it so very well. Still, when treated properly, it affects us deeply, inciting tears or clenched fists. Death can set us deep in thought, reflecting on the meaning of life.

Some types of horror do this differently, cheapening the lives of many to illustrate the value of a few, the heroes or villains.

The author must take care with death. Its nature, timing, and consequences are never trivial. When an important character dies, the ripples can magnify, altering the story’s direction and tone.

We ask many questions of death. Who is hurt, or devastated? Who is relieved? Where is the advantage? What institutions or cabals will restructure or fall to ashes? What further role will the bygone play? Will another raise his banner, step into her shoes?

While a character’s doom may close all her doors, it is sure to open new ones for her survivors, friend and foe. The masters of fiction tug our heartstrings and challenge our expectations with unimagined consequence and reactions that surprise and intuit the reader. And why not? What more fertile soil is there than the one thing we all have coming? We all see it differently, through lenses of religion or science, logic or emotion, fear or denial, but it touches every one of us. Family, friends, beloved artists who have touched our souls, all pass on.

And we stand in the wake of their passing, the ripples rolling over us. We bend and break, fight the tide, struggle on. Our heroes do the same, their hearts and minds burdened with loss and wonderment. They carry us along down to Charon’s landing, help us find the coin in our pockets, and reveal at once something of ourselves and something of their creators.

As an author, how have you used this powerful dramatic tool? Readers, what fictional deaths have affected you?

Logan L. Masterson is the author of Ravencroft Springs and Ravencroft Springs: The Feast of ‘69, Lovecraftian tales of Appalachia, and the Wheel of the Year series of fantasy single shots published by Pro Se Press. Look for his “Prime Movers” stories in the Capes & Clockwork anthology series, and “Shadow of the Wolf” in Luna’s Children II, both from Dark Oak Press. A published poet, arts journalist and unapologetic geek, he lives in Nashville, Tennessee with five dogs, two turtles, and a lovely wife.